Safety of Ticagrelor Compared to Clopidogrel in the Contemporary Management Through Invasive or Non-Invasive Strategies of Elderly Patients Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndromes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Clinical Management

2.3. Clinical Follow-Up

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Presentation and Clinical Management

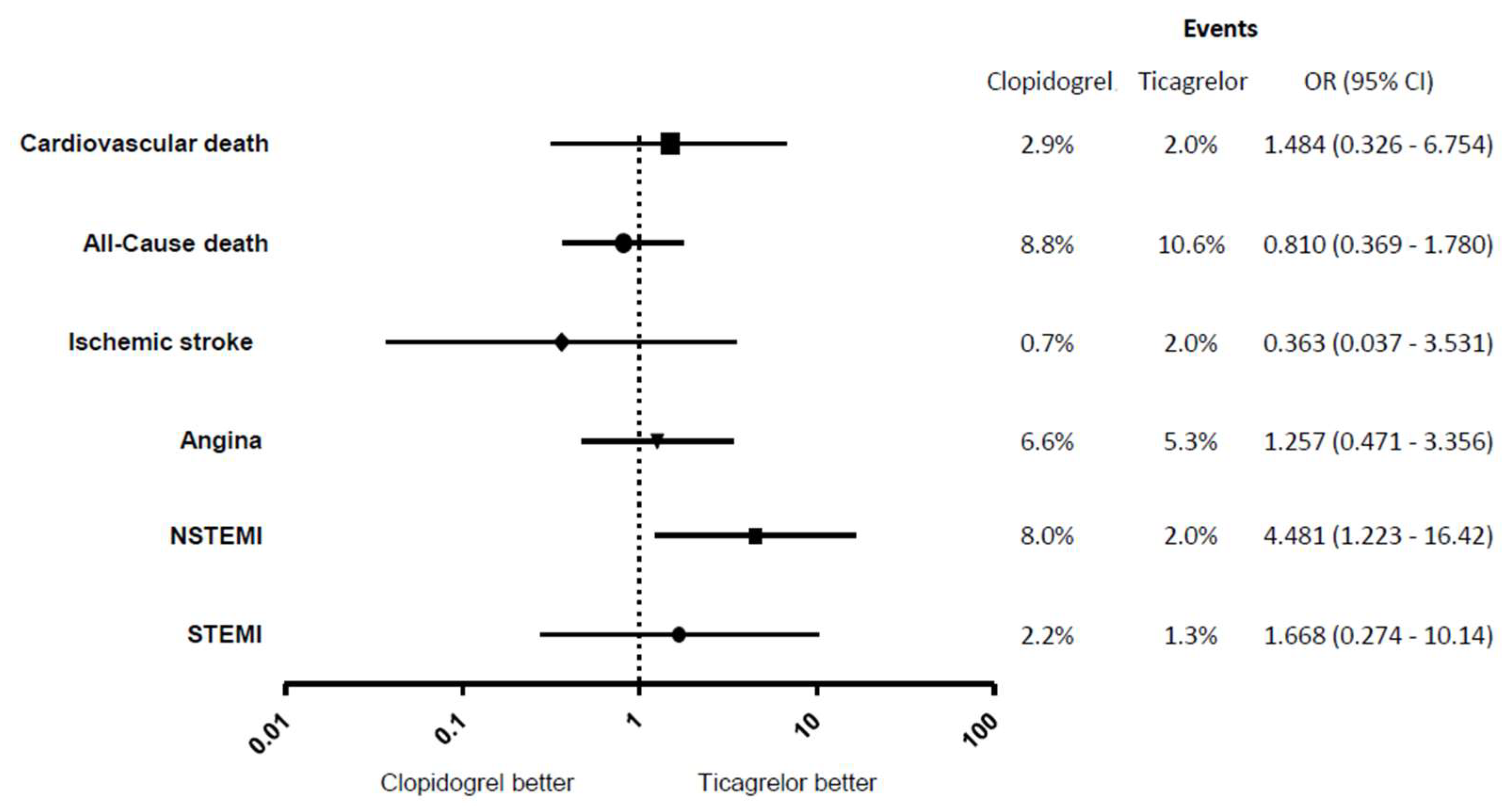

3.2. Clinical Follow-Up

4. Discussion

| Study | Country/Region | Population | Ticagrelor Use and Comparator | Bleeding Risk | Prognostic Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RENAMI/BleeMACS [31] | Global/Europe | ≥75 years | Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel | Non-significant increase in bleeding (HR 1.49) | Yes—↓ recurrent MI, ↓ all-cause mortality |

| SWEDEHEART [32] | Sweden | ≥80 years | Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel | Increased major bleeding (HR 1.48) | No—↑ all-cause mortality; net clinical harm |

| Bremen STEMI Registry [13] | Germany | ≥75 years | Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel | No difference in bleeding after one year (HR 1.00) | Yes—↓ MACCE, improved net clinical benefit |

| PLATO (Subgroup) [17] | Multinational RCT | ≥75 years | Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel | No significant increase in major bleeding (HR 1.02) | Yes—↓ CV death, MI, stroke |

| POPular AGE [22] | Netherlands RCT | ≥70 years | Clopidogrel vs. Ticagrelor/Prasugrel | Clopidogrel: Lower major bleeding (HR 0.57) | No difference in ischemic events |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisen, A.; Giugliano, R.P.; Braunwald, E. Updates on Acute Coronary Syndrome. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, K.P.; Newby, L.K.; Cannon, C.P.; Armstrong, P.W.; Gibler, W.B.; Rich, M.W.; Van de Werf, F.; White, H.D.; Weaver, W.D.; Naylor, M.D.; et al. Acute Coronary Care in the Elderly, Part I. Circulation 2007, 115, 2549–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.P.; Newby, L.K.; Armstrong, P.W.; Cannon, C.P.; Gibler, W.B.; Rich, M.W.; Van de Werf, F.; White, H.D.; Weaver, W.D.; Naylor, M.D.; et al. Acute Coronary Care in the Elderly, Part II. Circulation 2007, 115, 2570–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegn, N.; Abdelnoor, M.; Aaberge, L.; Endresen, K.; Smith, P.; Aakhus, S.; Gjertsen, E.; Dahl-Hofseth, O.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Gullestad, L.; et al. Invasive versus conservative strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris (After Eighty study): An open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunadian, V.; Mossop, H.; Shields, C.; Bardgett, M.; Watts, P.; Teare, M.D.; Pritchard, J.; Adams-Hall, J.; Runnett, C.; Ripley, D.P.; et al. Invasive Treatment Strategy for Older Patients with Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredsson, J.; Neely, B.; Neely, M.L.; Bhatt, D.L.; Goodman, S.G.; Tricoci, P.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Cornel, J.H.; White, H.D.; Fox, K.A.; et al. Predicting the risk of bleeding during dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndromes. Heart 2017, 103, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subherwal, S.; Bach, R.G.; Chen, A.Y.; Gage, B.F.; Rao, S.V.; Newby, L.K.; Wang, T.Y.; Gibler, W.B.; Ohman, E.M.; Roe, M.T.; et al. Baseline Risk of Major Bleeding in Non–ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2009, 119, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of Clopidogrel in Addition to Aspirin in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes without ST-Segment Elevation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Geraghty, O.C.; Mehta, Z.; Rothwell, P.M. Age-specific risks, severity, time course, and outcome of bleeding on long-term antiplatelet treatment after vascular events: A population-based cohort study. Lancet 2017, 390, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Montalescot, G.; Ruzyllo, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Neumann, F.-J.; Ardissino, D.; De Servi, S.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmucker, J.; Fach, A.; Marin, L.A.M.; Retzlaff, T.; Osteresch, R.; Kollhorst, B.; Hambrecht, R.; Pohlabeln, H.; Wienbergen, H. Efficacy and Safety of Ticagrelor in Comparison to Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients with ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarctions. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berwanger, O.; Nicolau, J.C.; Carvalho, A.C.; Jiang, L.; Goodman, S.G.; Nicholls, S.J.; Parkhomenko, A.; Averkov, O.; Tajer, C.; Malaga, G.; et al. Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel After Fibrinolytic Therapy in Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffi, M.; Patrono, C.; Collet, J.-P.; Mueller, C.; Valgimigli, M.; Andreotti, F.; Bax, J.J.; Borger, M.A.; Brotons, C.; Chew, D.P.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 267–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.V.; O’gRady, K.; Pieper, K.S.; Granger, C.B.; Newby, L.K.; Van de Werf, F.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Califf, R.M.; Harrington, R.A. Impact of Bleeding Severity on Clinical Outcomes Among Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husted, S.; James, S.; Becker, R.C.; Horrow, J.; Katus, H.; Storey, R.F.; Cannon, C.P.; Heras, M.; Lopes, R.D.; Morais, J.; et al. Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2012, 5, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Serebruany, V. CRUSADE Score is Superior to Platelet Function Testing for Prediction of Bleeding in Patients Following Coronary Interventions. eBioMedicine 2017, 21, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Assi, E.; Gracía-Acuña, J.M.; Ferreira-González, I.; Peña-Gil, C.; Gayoso-Diz, P.; González-Juanatey, J.R. Evaluating the Performance of the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE) Bleeding Score in a Contemporary Spanish Cohort of Patients with Non–ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2010, 121, 2419–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, J.-P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sang, W.; Yang, K.; Xu, F.; Xu, F.; et al. Comparison of Safety and Efficacy Between Clopidogrel and Ticagrelor in Elderly Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 743259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; de Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Gin, M.T.J.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlinden, N.J.; Coons, J.C.; Iasella, C.J.; Kane-Gill, S.L. Triple Antithrombotic Therapy with Aspirin, P2Y12 Inhibitor, and Warfarin After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 22, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreou, I.; Briasoulis, A.; Pappas, C.; Ikonomidis, I.; Alexopoulos, D. Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel as Part of Dual or Triple Antithrombotic Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2018, 32, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellino, M.; Sànchez, F.A.; Boasi, V.; Perri, D.; Tacchi, C.; Secco, G.G.; Cattunar, S.; Pistis, G.; Mascelli, G. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in real-world patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction: 1-year results by propensity score analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Keeble, C.; Anderson, M.; Somers, K.; Burton-Wood, N.; Harland, C.; Baxter, P.; McLenachan, J.; Blaxill, J.; Blackman, D.J.; et al. Real-world comparison of clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Open Heart 2019, 6, e000951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, D.S.; Leong, T.K.; Chang, T.I.; Solomon, M.D.; Hlatky, M.A.; Go, A.S. Association of Spontaneous Bleeding and Myocardial Infarction with Long-Term Mortality after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, R.; Pocock, S.; Nikolsky, E.; Dangas, G.D.; Clayton, T.; Claessen, B.E.; Caixeta, A.; Feit, F.; Manoukian, S.V.; White, H.; et al. Impact of Bleeding on Mortality after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Results from a Patient-Level Pooled Analysis of the REPLACE-2 (Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events), ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy), and HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Trials. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscaglia, S.; Guiducci, V.; Escaned, J.; Moreno, R.; Lanzilotti, V.; Santarelli, A.; Cerrato, E.; Sacchetta, G.; Jurado-Roman, A.; Menozzi, A.; et al. Complete or Culprit-Only PCI in Older Patients with Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savonitto, S.; De Luca, G.; De Servi, S. Treatment of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the elderly: The Senior-Rita trial. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2025, 27, iii131–iii136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, M.; Careggio, A.; Biolè, C.A.; Quadri, G.; Quiros, A.; Raposeiras-Roubin, S.; Abu-Assi, E.; Kinnaird, T.; Ariza-Solè, A.; Liebetrau, C.; et al. Ticagrelor or Clopidogrel after an Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Elderly: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis from 16,653 Patients Treated with PCI Included in Two Large Multinational Registries. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 35, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szummer, K.; Montez-Rath, M.E.; Alfredsson, J.; Erlinge, D.; Lindahl, B.; Hofmann, R.; Ravn-Fischer, A.; Svensson, P.; Jernberg, T. Comparison between Ticagrelor and Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients with an Acute Coronary Syndrome Insights from the SWEDEHEART Registry. Circulation 2020, 142, 1700–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clopidogrel (137) | Ticagrelor (151) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 80 ± 5 | 81 ± 5 | 0.062 | |

| Gender | Male | 56% | 53% | 0.722 |

| Female | 44% | 47% | ||

| BMI | 24 ± 8 | 26 ± 4 | 0.953 | |

| Creatinine | 108 ± 74 | 105 ± 85 | 0.806 | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Previous MI | 29.9% | 30.5% | 1.000 | |

| Angina | 29.2% | 31.8% | 0.701 | |

| Hypertension | 73.7% | 72.8% | 0.895 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 42.3% | 47.0% | 0.477 | |

| PVD | 5.1% | 6.6% | 0.626 | |

| Stroke | 21.2% | 20.5% | 1.000 | |

| CKD | 13.9% | 18.5% | 0.339 | |

| Heart failure | 13.9% | 11.9% | 0.601 | |

| Previous PCI | 16.8% | 17.9% | 0.877 | |

| Previous CABG | 12.4% | 13.9% | 0.731 | |

| Family history of CAD | 15.3% | 16.6% | 0.872 | |

| Smoker | Current | 11.4% | 7.9% | 0.422 |

| Ex-Smoker | 40.2% | 33.8% | 0.393 | |

| Diabetes | Insulin depedent | 10.9% | 10.0% | 0.848 |

| Non-insulin | 16.8% | 19.9% | 0.545 |

| Clopidogrel (137) | Ticagrelor (151) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation | STEMI | 31.4% | 43.1% | 0.051 |

| NSTEMI | 68.6% | 56.9% | ||

| ECG changes | ST elevation | 27.7% | 37.1% | 0.100 |

| ST depression | 24.1% | 19.9% | 0.259 | |

| T wave changes | 18.2% | 18.5% | 1.000 | |

| Left bundle branch block | 3.6% | 6.0% | 0.420 | |

| Other acute changes | 11.7% | 10.6% | 0.852 | |

| No acute change | 13.9% | 7.9% | 0.123 | |

| Unknown | 0.7% | 0 | ||

| Kilip class | ≥3 | 11.7% | 10.6% | 0.852 |

| Infarction territory | Anterior | 25.5% | 33.8% | 0.156 |

| Lateral | 3.6% | 6.0% | 0.420 | |

| Inferior | 21.2% | 24.5% | 0.575 | |

| Posterior | 2.9% | 2.6% | 1.000 | |

| Indeterminate | 11.7% | 11.3% | 1.000 | |

| Unknown | 35.0% | 21.9% | 0.018 | |

| Treatment | Primary PCI | 23.4% | 31.7% | 0.116 |

| PCI | 48.1% | 57.0% | 0.157 | |

| Medical Management | 51.9% | 43.0% | ||

| Crusade score | 39 ± 13 | 37 ± 13 | 0.220 | |

| Discharge LV function | Good | 51.8% | 52.3% | 1.000 |

| Moderately impaired | 25.5% | 29.8% | 0.433 | |

| Poor | 6.6% | 7.3% | 1.000 | |

| Not assessed | 16.1% | 10.6% | 0.222 | |

| Discharge Medications | Statin | 88.3% | 92.7% | 0.228 |

| ACE inhibitor | 74.4% | 79.1% | 0.489 | |

| Beta-blocker | 78.8% | 80.1% | 0.779 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazir, A.; Shetty Ujjar, S.; Saba, S.; Ruparelia, N.; Spyrou, N.; Fan, L. Safety of Ticagrelor Compared to Clopidogrel in the Contemporary Management Through Invasive or Non-Invasive Strategies of Elderly Patients Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndromes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165629

Nazir A, Shetty Ujjar S, Saba S, Ruparelia N, Spyrou N, Fan L. Safety of Ticagrelor Compared to Clopidogrel in the Contemporary Management Through Invasive or Non-Invasive Strategies of Elderly Patients Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(16):5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165629

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazir, Anum, Smrthi Shetty Ujjar, Seemi Saba, Neil Ruparelia, Nicos Spyrou, and Lampson Fan. 2025. "Safety of Ticagrelor Compared to Clopidogrel in the Contemporary Management Through Invasive or Non-Invasive Strategies of Elderly Patients Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndromes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 16: 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165629

APA StyleNazir, A., Shetty Ujjar, S., Saba, S., Ruparelia, N., Spyrou, N., & Fan, L. (2025). Safety of Ticagrelor Compared to Clopidogrel in the Contemporary Management Through Invasive or Non-Invasive Strategies of Elderly Patients Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndromes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(16), 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165629