Efficacy of Noofen 250 mg Capsules for the Management of Anxious–Neurotic Symptoms in Patients with Adjustment Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Stress and Health

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objectives

2.2. Intervention

2.3. The Adjustment Disorder New Module 20-Item Questionnaire (ADNM-20)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Adverse Events

3. Results

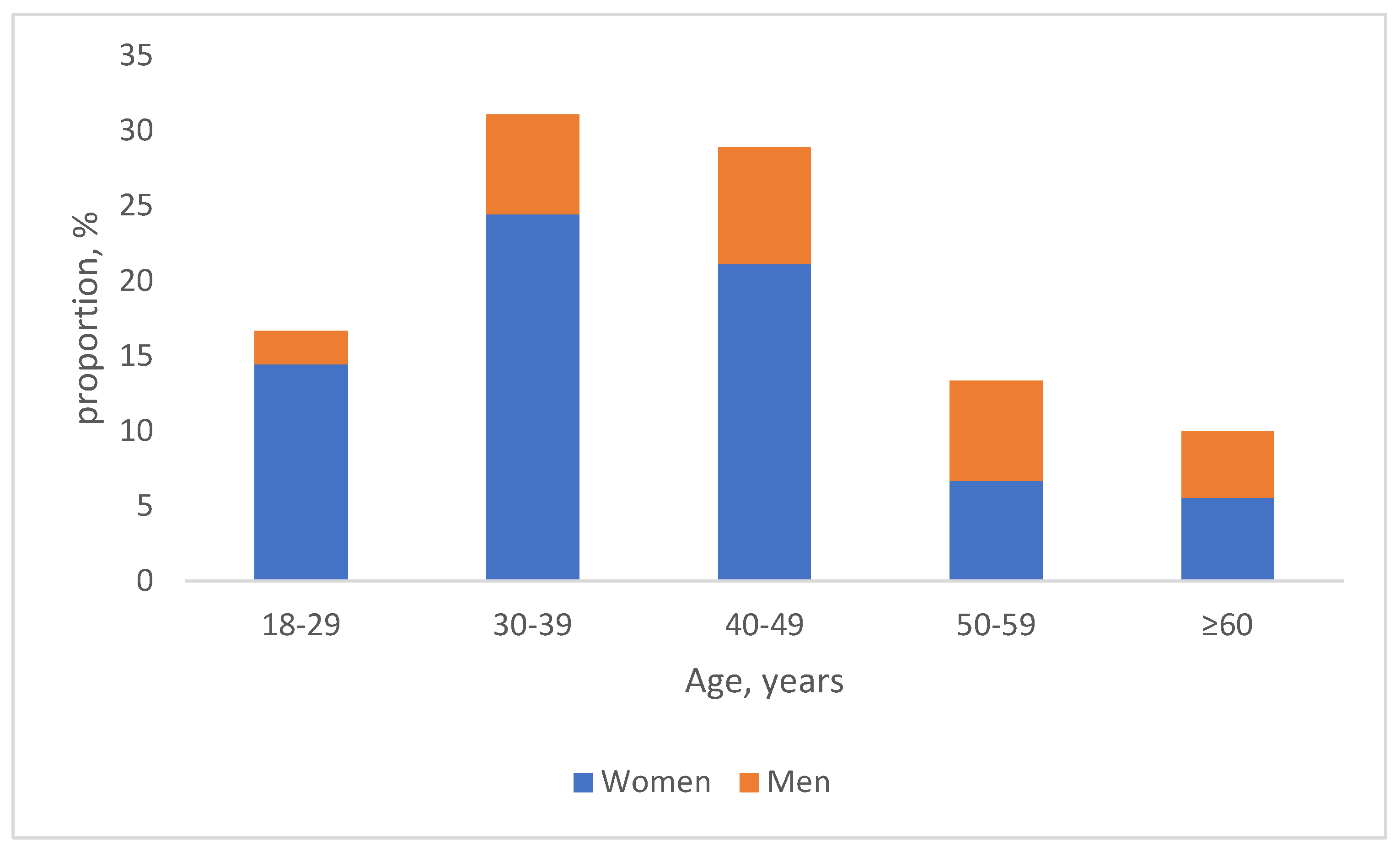

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

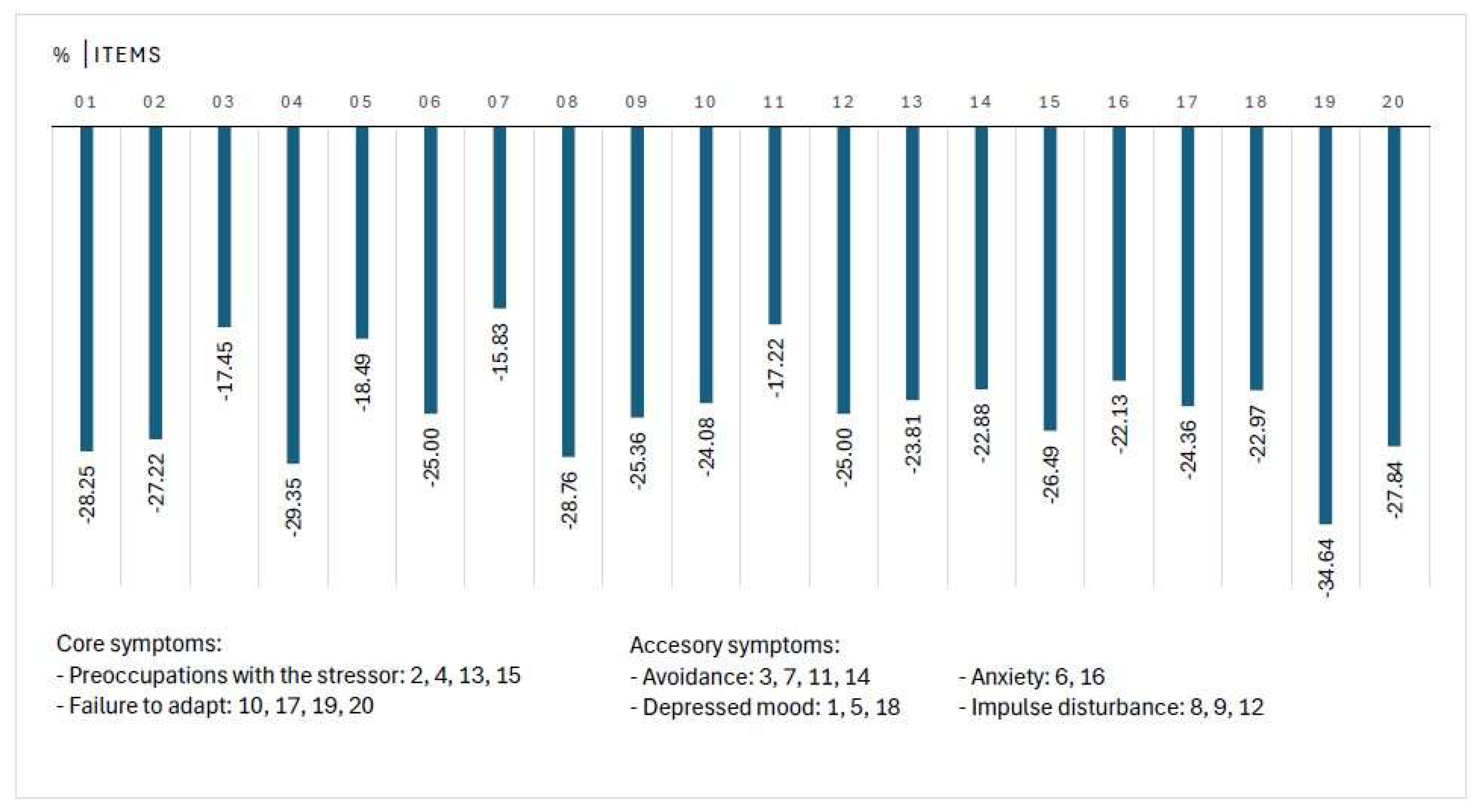

3.2. Change in Individual Items of ADNM-20

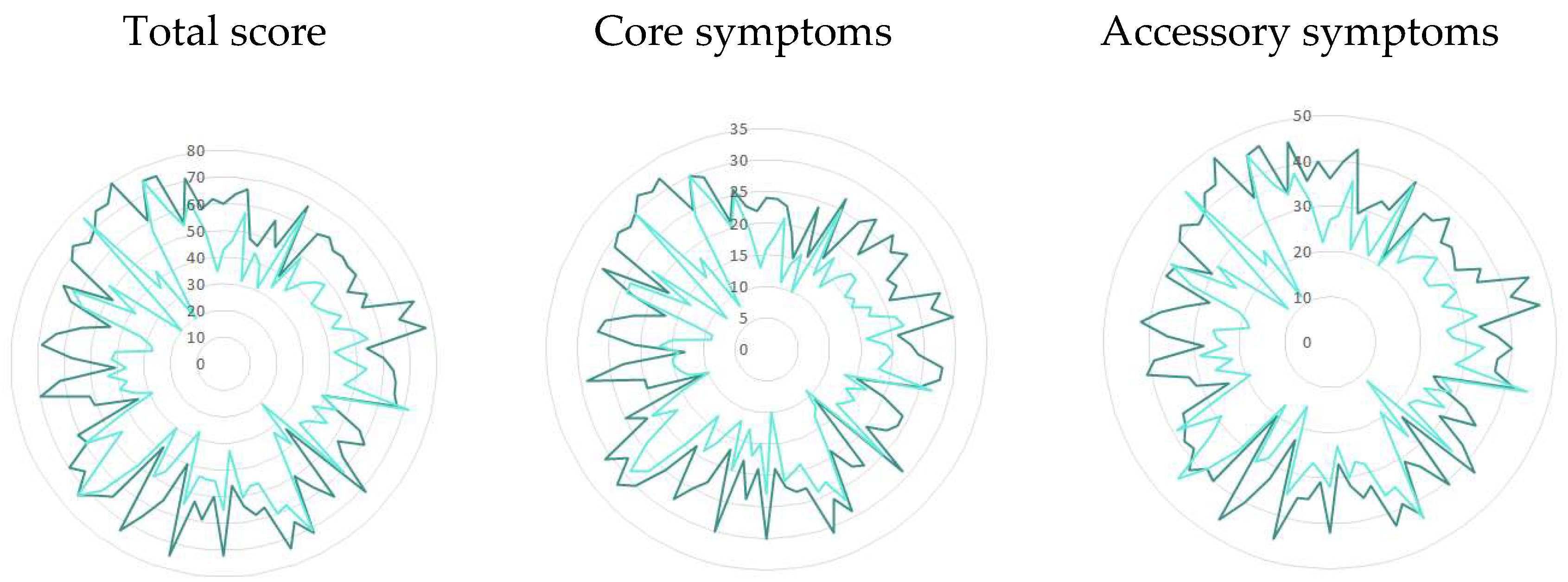

3.3. Consistency Between Patient and Clinician Reported Outcomes

3.4. ADNM-20 Questionnaire, User Experience

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADNM-20 | Adjustment Disorder New Module 20-item questionnaire |

| AjD | Adjustment Disorder |

| ATC | Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision |

| n/a | Not applicable |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcome |

| QE84 | ICD-11 code for acute stress reaction |

| QD85 | ICD-11 code for burnout syndrome |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ClinRO | Clinician-reported outcome |

References

- Reed, G.M.; Mendonça Correia, J.; Esparza, P.; Saxena, S.; Maj, M. The WPA-WHO Global Survey of Psychiatrists’ Attitudes Towards Mental Disorders Classification. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, M.L.; Agathos, J.A.; Metcalf, O.; Gibson, K.; Lau, W. Adjustment Disorder: Current Developments and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Stress. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Chu, B.; Marwaha, K.; Sanvictores, T.; Awosika, A.O.; Ayers, D. Physiology, Stress Reaction [Updated 7 May 2024]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). 2024. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#264310751 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Lindsäter, E.; Svärdman, F.; Wallert, J.; Ivanova, E.; Söderholm, A.; Fondberg, R.; Nilsonne, G.; Cervenka, S.; Lekander, M.; Rück, C. Exhaustion disorder: Scoping review of research on a recently introduced stress-related diagnosis. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, M.L.; Metcalf, O.; Watson, L.; Phelps, A.; Varker, T. A Systematic Review of Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adjustment Disorder in Adults. J. Trauma. Stress 2018, 31, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noofen (Phenibut) Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). Available online: https://dati.zva.gov.lv/zalu-registrs/?iss=1&q=Noofen&IK-1=1&IK-2=2&NAC=on&SAT=on&DEC=on&ESC=on&ESI=on&PIM=on&RNE=on (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Blackburn, T.P. GABAB Receptor Pharmacology: A Tribute to Norman Bowery; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://books.google.lv/books?id=_iMDQOA2UIsC&pg=PA25 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Department of Psychology, University of Zurich. The Adjustment Disorder—New Module 20 (ADNM-20) Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.psychology.uzh.ch/dam/jcr:15220404-d1b2-4d9a-9661-f1709b4ca3f4/ADNM_20_Homepage_English.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Lorenz, L.; Bachem, R.C.; Maercker, A. The Adjustment Disorder—New Module 20 as a Screening Instrument: Cluster Analysis and Cut-off Values. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 7, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bachem, R.; Perkonigg, A.; Stein, D.J.; Maercker, A. Measuring the ICD-11 adjustment disorder concept: Validity and sensitivity to change of the Adjustment Disorder—New Module questionnaire in a clinical intervention study. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 26, e1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Republic of Latvia Cabinet Regulation No. 47. Pharmacovigilance Procedures. Adopted 22 January 2013. Issued Pursuant to Section 5, Paragraph 24 of the Pharmacy Law. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/254434-pharmacovigilance-procedures (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Maercker, A.; Brewin, C.R.; Bryant, R.A.; Cloitre, M.; van Ommeren, M.; Jones, L.M.; Humayan, A.; Kagee, A.; Llosa, A.E.; Rousseau, C.; et al. Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazlauskas, E.; Zelviene, P.; Lorenz, L.; Quero, S.; Maercker, A. A scoping review of ICD-11 adjustment disorder research. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 8, 1421819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupats, E.; Vrublevska, J.; Zvejniece, B.; Vavers, E.; Stelfa, G.; Zvejniece, L.; Dambrova, M. Safety and tolerability of the anxiolytic and nootropic drug phenibut: A systematic review of clinical trials and case reports. Pharmacopsychiatry 2020, 53, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stressful Life Events * | Reporters, % |

|---|---|

| Too much/too little work | 63 |

| Pressure to meet deadlines/time pressure | 47 |

| Family conflicts | 46 |

| Conflicts in working life | 30 |

| Illness of a loved one | 30 |

| Financial problems | 30 |

| Death of a loved one | 19 |

| Termination of an important leisure activity | 19 |

| Own serious illness | 17 |

| Moving to a new home | 13 |

| Divorce/separation | 11 |

| Unemployment | 11 |

| Conflicts with neighbors | 6 |

| Assault | 6 |

| Serious accident | 4 |

| Adjustment due to retirement | 1 |

| Any other stressful event | 28 |

| Summary Points | Baseline, Mean (SD) | After Treatment, Mean (SD) | Difference ^ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 60.3 (10.5) | 45.5 (12.3) | 14.8 (11.3) |

| Core symptoms | 24.0 (4.9) | 17.4 (5.2) | 6.6 (4.9) |

| Accessory symptoms | 36.3 (6.1) | 28.1 (7.4) | 8.2 (6.9) |

| Subscales points | Baseline, mean (SD) | After treatment, mean (SD) | Difference ^ |

| Preoccupations with stressor | 12.5 (2.7) | 9.2 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.7) |

| Failure to adapt | 11.5 (2.9) | 8.3 (2.7) | 3.2 (2.7) |

| Avoidance | 12.0 (2.5) | 9.8 (2.8) | 2.2 (2.8) |

| Depressed mood | 8.8 (2.1) | 6.7 (2.0) | 2.1 (2.2) |

| Anxiety | 5.8 (1.4) | 4.4 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.5) |

| Impulse disturbance | 9.7 (2.0) | 7.1 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.2) |

| Symptom severity * | Baseline | After treatment | p value |

| Low | 12.2% | 7.8% | <0.19 |

| Moderate | 31.1% | 55.6% | <0.001 |

| High | 56.7% | 22.2% | <0.001 |

| Under the lower cut-off value | n/a | 14.4% | - |

| Clinician’s Assessment of Symptom Change from Baseline | Change in ADNM-20 Total Score; Points; Mean (SD); Min, Max Difference from Baseline; Significance |

|---|---|

| Improved significantly (n = 33), 36.7% | −8.8 (4.9) −3; −60, p < 0.001 |

| Improved (n = 49), 55.4% | −21.3 (10.5), 1; −19, p < 0.001 |

| Not improved (n = 8), 8.9% | 0.75 (3.1) −3; 6, p = 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tērauds, E.; Dansone, G.; Troshina, Y. Efficacy of Noofen 250 mg Capsules for the Management of Anxious–Neurotic Symptoms in Patients with Adjustment Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155570

Tērauds E, Dansone G, Troshina Y. Efficacy of Noofen 250 mg Capsules for the Management of Anxious–Neurotic Symptoms in Patients with Adjustment Disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155570

Chicago/Turabian StyleTērauds, Elmārs, Guna Dansone, and Yulia Troshina. 2025. "Efficacy of Noofen 250 mg Capsules for the Management of Anxious–Neurotic Symptoms in Patients with Adjustment Disorder" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155570

APA StyleTērauds, E., Dansone, G., & Troshina, Y. (2025). Efficacy of Noofen 250 mg Capsules for the Management of Anxious–Neurotic Symptoms in Patients with Adjustment Disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155570