A Quality Assessment and Evaluation of Credible Online Dietary Resources for Patients with an Ileoanal Pouch

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.4. Content Quality Analysis

2.5. Readability of Written Information

2.6. Content Analysis

2.7. Shared Decision-Making Analysis

3. Results

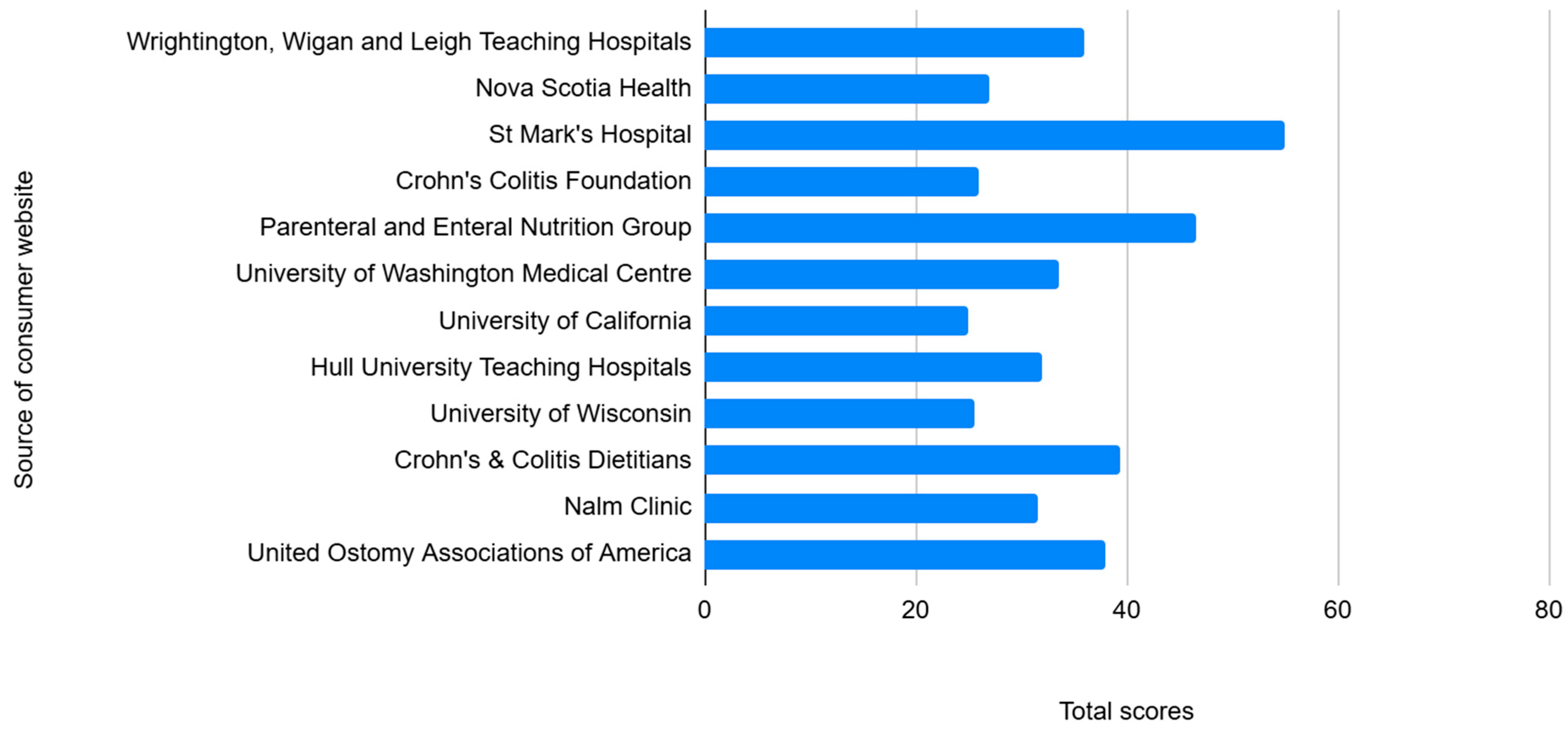

3.1. Content Quality

3.2. Readability

3.3. Summative Content Analysis

- General dietary advice for pouch: Recommendations of specific food to be consumed were most commonly mentioned (n = 10 websites), where some explained reasons such as “protein-containing foods for repair of muscle” and others just provided lists of foods to include. Foods to avoid (n = 9) also varied and included high-sugar foods and spicy foods. Eating styles (n = 9), such as the timing of meals and specific nutrients to consume (n = 9), were the next most common and also varied in specific details. The implementation of a pre-surgical diet using the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol was the least common (n = 1).

- Dietary strategies for symptom management: Most websites provided advice on specific foods to decrease output (n = 8) followed by increasing output (n = 7), reducing anal irritation (n = 7), increasing wind (n = 6), passing undigested food (n = 4), bloating (n = 4), increasing stool odour (n = 4), decreasing stool odour (n = 1), loose stools (n = 3), and increasing urgency (n = 2). There were duplicates in this, with the same table being used across the St. Mark’s-related documents. Most listed individual foods, beverages, and/or ingredients, while some included foods with multiple ingredients, such as suet pudding and coleslaw.

- Addressing risks associated with having a pouch: Dehydration was the most commonly mentioned risk (n = 9), followed by pouchitis (n = 5), bowel obstructions, (n = 3), incontinence or leakage (n = 2), and (abnormal) bile acid malabsorption (n = 1).

- Optimisation of nutritional intake: Websites focused on specific nutrients to consume or increase in pouches (n = 9), as well as nutrients of concern specific to pouches (n = 5).

3.4. Shared Decision-Making

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spinelli, A.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Surgical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simchuk, E.J.; Thirlby, R.C. Risk factors and true incidence of pouchitis in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. World J. Surg. 2000, 24, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightner, A.L.; Mathis, K.L.; Dozois, E.J.; Hahnsloser, D.; Loftus, E.V.; Raffals, L.E., Jr.; Pemberton, J.H. Results at Up to 30 Years After Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis for Chronic Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, J.C.; Winter, D.C.; Neary, P.; Murphy, A.; Redmond, H.P.; Kirwan, W.O. Quality of life after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: An evaluation of diet and other factors using the Cleveland Global Quality of Life instrument. Dis. Colon Rectum 2002, 45, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ardalan, Z.S.; Livingstone, K.M.; Polzella, L.; Avakian, J.; Rohani, F.; Sparrow, M.P.; Gibson, P.R.; Yao, C.K. Perceived dietary intolerances, habitual intake and diet quality of patients with an ileoanal pouch: Associations with pouch phenotype (and behaviour). Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 2095–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianco, O.; Tulchinsky, H.; Lusthaus, M.; Ofer, A.; Santo, E.; Vaisman, N.; Dotan, I. Diet of patients after pouch surgery may affect pouch inflammation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 6458–6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godny, L.; Maharshak, N.; Reshef, L.; Goren, I.; Yahav, L.; Fliss-Isakov, N.; Gophna, U.; Tulchinsky, H.; Dotan, I. Fruit Consumption is Associated with Alterations in Microbial Composition and Lower Rates of Pouchitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.S.; Yao, C.K.; Costello, S.P.; Andrews, J.M.; Bryant, R.V. Food avoidance, restrictive eating behaviour and association with quality of life in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic scoping review. Appetite 2021, 167, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelencich, E.; Truong, E.; Widaman, A.M.; Pignotti, G.; Yang, L.; Jeon, Y.; Weber, A.T.; Shah, R.; Smith, J.; Sauk, J.S.; et al. Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Prevalent Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1282–1289.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortinsky, K.J.; Fournier, M.R.; Benchimol, E.I. Internet and electronic resources for inflammatory bowel disease: A primer for providers and patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Cao, L.; Liu, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W. Factors associated with internet use and health information technology use among older people with multi-morbidity in the United States: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2018. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujnowska-Fedak, M.M.; Waligóra, J.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. The Internet as a Source of Health Information and Services. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1211, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gravina, A.G.; Pellegrino, R.; Cipullo, M.; Palladino, G.; Imperio, G.; Ventura, A.; Auletta, S.; Ciamarra, P.; Federico, A. May ChatGPT be a tool producing medical information for common inflammatory bowel disease patients’ questions? An evidence-controlled analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denniss, E.; Lindberg, R.; McNaughton, S.A. Quality and accuracy of online nutrition-related information: A systematic review of content analysis studies. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M. Using the Internet: Skill related problems in users’ online behavior. Interact. Comput. 2009, 21, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutue of Health and Care Excellence. Standards Framework for Shared-Decision-Making Support Tools, Including Patient Decision Aids United Kingdom: NICE. 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd8 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Charnock, D.; Shepperd, S.; Needham, G.; Gann, R. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1999, 53, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Usman, M.; Muhammad, F.; Rehman Su Khan, I.; Idrees, M.; Irfan, M.; Glowacz, A. Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, R.; Saito, K.; Yachi, Y.; Ibe, Y.; Kodama, S.; Asumi, M.; Horikawa, C.; Saito, A.; Heianza, Y.; Kondo, K.; et al. Quality of Internet information related to the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesch, R. A new readability yardstick. J. Appl. Psychol. 1948, 32, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.M.L.; Martin, A.G. Analysis of patient information leaflets provided by a district general hospital by the Flesch and Flesch–Kincaid method. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Cunningham, A.; Hutchings, H.; Harris, D.A.; Evans, M.D.; Harji, D. Quality of internet information to aid patient decision making in locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. Surgeon 2022, 20, e382–e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, T.M.; Sacchi, M.; Mortensen, N.J.; Spinelli, A. Assessment of the Quality of Patient-Orientated Information on Surgery for Crohn’s Disease on the Internet. Dis. Colon Rectum 2015, 58, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, M.; Yeung, T.M.; Spinelli, A.; Mortensen, N.J. Assessment of the quality of patient-orientated internet information on surgery for ulcerative colitis. Color. Dis. 2015, 17, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.M.; Marshall, J.H.; Lee, M.J.; Jones, G.L.; Brown, S.R.; Lobo, A.J. A Systematic Review of Internet Decision-Making Resources for Patients Considering Surgery for Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, S.; Clifford, S.; Pinkney, T.; Thompson, D.; Mathers, J. Assessment of the quality of online patient information resources for patients considering parastomal hernia treatment. Color. Dis. 2024, 26, 1014–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panés, J.; de Lacy, A.M.; Sans, M.; Soriano, A.; Piqué, J.M. Elevado índice de consultas por Internet de los pacientes catalanes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2002, 25, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruani, M.A.; Reiss, M.J.; Kalea, A.Z. Diet-Nutrition Information Seeking, Source Trustworthiness, and Eating Behavior Changes: An International Web-Based Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruani, M.A.; Reiss, M.J. Susceptibility to COVID-19 Nutrition Misinformation and Eating Behavior Change during Lockdowns: An International Web-Based Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassier, P.; Chhim, A.S.; Andreeva, V.A.; Hercberg, S.; Latino-Martel, P.; Pouchieu, C.; Touvier, M. Seeking health- and nutrition-related information on the Internet in a large population of French adults: Results of the NutriNet-Santé study. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2039–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Wu, X.; Shen, B. Low levels of vitamin D are common in patients with ileal pouches irrespective of pouch inflammation. J. Crohns Colitis. 2013, 7, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana, R.J.; Torres, E.A.; Arroyo, J.M.; Rivera, C.E.; Sánchez, C.J.; Morales, L. Iron-deficiency anemia as presentation of pouchitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2007, 41, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeev, M.; Cohen, J.; Wakefield, C.E.; Fardell, J.E.; Cohn, R.J. Decision Aid for Nutrition Support in Pediatric Oncology: A Pilot Study. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.C.; Lee, W.Y.; Hsu, H.C.; Creedy, D.K.; Tsao, Y. Effectiveness of a Digital Decision Aid for Nutrition Support in Women with Gynaecological Cancer: A Comparative Study. Nutr. Cancer 2024, 76, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almario, C.V.; Keller, M.S.; Chen, M.; Lasch, K.; Ursos, L.; Shklovskaya, J.; Melmed, G.Y.; Spiegel, B.M.R. Optimizing Selection of Biologics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Development of an Online Patient Decision Aid Using Conjoint Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Organisation | URL | Type of Organisation | City and Country of Origin | Format of Diet Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Teaching Hospitals | https://www.wwl.nhs.uk/media/.leaflets/5ffeb6edcf7e70.74545301.pdf (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Government healthcare | Wigan, UK | Four-page patient leaflet |

| Nova Scotia Health | https://www.nshealth.ca/patient-education-resources/0555 (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Government healthcare | Halifax, Canada | Eight-page leaflet |

| St. Mark’s Hospital | https://www.stmarkshospital.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Healthy-eating-for-people-with-internal-pouches.pdf (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Government healthcare | London, UK | Ten-page leaflet |

| Crohn’s Colitis Foundation | https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/patientsandcaregivers/diet-and-nutrition/surgery-and-nutrition/j-pouch-surgery-nutrition (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Foundations/associations | New York City, USA | Single online page |

| Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Group | https://www.peng.org.uk/pdfs/diet-sheets/internal-pouches.pdf (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Foundations/associations | Birmingham, UK | Six-page patient leaflet |

| University of Washington Medical Centre | https://healthonline.washington.edu/sites/default/files/record_pdfs/J-Pouch_Nutritional_Guidelines_9_09.pdf (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Academic institution | Seattle, USA | Two-page leaflet |

| University of California | https://www.ucsfhealth.org/education/special-concerns-for-people-with-j-pouches (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Academic institution | Oakland, USA | Single online page with various issues related to surgery, including a section on diet |

| Hull University Teaching Hospitals | https://www.hey.nhs.uk/patient-leaflet/eating-with-an-ileoanal-pouch/#:~:text=Eating%20small%20amounts%20more%20frequently,as%20Quorn%2C%20Tofu%20and%20tempeh (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Government healthcare | Hull, UK | Single online page |

| University of Wisconsin | https://patient.uwhealth.org/healthfacts/355 (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Academic institution | Madison, USA | Two-page leaflet |

| Crohn’s & Colitis Dietitians | https://crohnsandcolitisdietitians.com/j-pouch-surgery-what-to-eat-the-nutritional-implications/ (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Private clinic | USA | Blog-style page |

| Nalm Clinic | https://nalmclinic.com/blog-1/2022/2/14/is-diet-important-with-a-j-pouch (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Private clinic | London, UK | Blog-style page |

| United Ostomy Associations of America | https://www.ostomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IleoanalReservoir_J-Pouch-Guide.pdf (accessed 27 Jun 2024) | Foundations/associations | Biddeford, USA | Twenty-nine-page patient leaflet about an internal reservoir—including a section on diet |

| Source | Health Condition, Decision, and Available Options | Details of Available Options | Support for Person’s Values, Circumstances, and Preferences | Use of Language and Numbers/Flesch–Kincaid (Readability) Score | Formats and Availability | Evidence Sources | Patient Involvement and Co-Production | Risks and Benefits | Review Cycle and Declaration of Interests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Teaching Hospitals | Partial | Yes | No | Language easy to understand but no figures or numbers. No diagrams or numbers, but pictures and tables to break up text. | 62.6 | Yes—“this leaflet is also available in audio, large print, Braille and other languages upon request” | No | No | Partial | Partial |

| Nova Scotia Health | Partial | Yes | No | Language easy to understand. No diagrams or numbers, but pictures and tables to break up text. | 73.5 | Yes—website with PDF print out available with links to online pamphlets/resources | No | No | No | Partial |

| St. Mark’s Hospital | Partial | Partial | No | Fairly easy to understand. However, low Flesch–Kincaid score. No diagrams or numbers, but pictures and tables to break up text. | 43.1 | Yes—online website for PDF print out. Mentions discussing decision-making with HCP | Partial | Yes | Partial | Yes |

| Crohn’s Colitis Foundation | No | No | No | Fairly easy to understand language. However, low Flesch–Kincaid. No diagrams, numbers, or tables. | 47.6 | Single online page | Yes | No | No | No |

| Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Group | Partial | Yes | No | Fairly easy to understand. However, low Flesch–Kincaid score. No diagrams or numbers, but text is broken up by a table. | 49.7 | Yes—six-page website for PDF print out | Partial | No | Partial | No |

| University of Washington Medical Centre | Partial | Partial | No | Language easy to understand. All of the text in dot points and a table. | 70.6 | Yes, two-page online website PDF for print out | No | No | No | Partial |

| University of California | Yes | Partial | No | Fairly easy to understand language with Flesch Kincaid score. No use of diagrams, visuals, numbers, or tables. | 59.3 | Single online page | Partial | No | Yes | No |

| Hull University Teaching Hospitals | Partial | Partial | No | Language easy to understand. Most of the text in dot points, also a table. | 64.4 | Yes—online site is translatable into seven languages | No | No | Partial | Partial |

| University of Wisconsin | Partial | Partial | No | Language easy to understand. No figures, numbers, or tables. | 70.4 | Double page online PDF for print | No | No | Partial | No |

| Crohn’s & Colitis Dietitians | Yes | Partial | No | Fairly easy to understand language but does get technical when discussing studies. Flesch–Kincaid score low. No use of diagrams, pictures, or numbers. | 45.4 | Online webpage | Partial | No | Partial | Partial |

| Nalm Clinic | No | No | No | Fairly easy to understand language; however, does get technical when discussing studies. Flesch–Kincaid score low. No use of diagrams, pictures, or numbers. | 42.4 | Online webpage | Partial | No | Partial | No |

| United Ostomy Associations of America | Partial | Partial | No | Fairly easy to understand language but does get technical in certain sections. Flesch–Kincaid score low. Use of diagrams and tables to support text. | 49.7 | Online booklet and guidebook with PDF print out available | Yes | Yes | Partial | Yes |

| Category | Codes | No. of Websites |

|---|---|---|

| General dietary advice for pouch | Pre-operative nutrition | 1 |

| Initial post-operative diet | 7 | |

| Eating styles | 9 | |

| Foods to include | 10 | |

| Foods to avoid | 9 | |

| Long-term diet | 3 | |

| Use of supplements | 4 | |

| Diet strategies for symptom management | Decrease output | 8 |

| Increase output | 7 | |

| Anal irritation | 7 | |

| Increase wind | 6 | |

| Passing undigested food | 4 | |

| Bloating | 4 | |

| Increase stool odour | 4 | |

| Decrease stool odour | 1 | |

| Loose stools | 3 | |

| Increased urgency | 2 | |

| Addressing risks associated with having a pouch | Dehydration | 9 |

| Pouchitis | 5 | |

| Bowel obstruction | 3 | |

| Bile acid malabsorption | 1 | |

| Incontinence or leakage | 2 | |

| Optimisation of nutritional intake | Nutrients to consume/increase specific to pouches | 9 |

| Nutrients of concern specific to pouches | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rhys-Jones, D.R.; Ghersin, I.; Argyriou, O.; Blackwell, S.; Lester, J.; Gibson, P.R.; Halmos, E.P.; Ardalan, Z.; Warusavitarne, J.; Sahnan, K.; et al. A Quality Assessment and Evaluation of Credible Online Dietary Resources for Patients with an Ileoanal Pouch. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155348

Rhys-Jones DR, Ghersin I, Argyriou O, Blackwell S, Lester J, Gibson PR, Halmos EP, Ardalan Z, Warusavitarne J, Sahnan K, et al. A Quality Assessment and Evaluation of Credible Online Dietary Resources for Patients with an Ileoanal Pouch. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155348

Chicago/Turabian StyleRhys-Jones, Dakota R., Itai Ghersin, Orestis Argyriou, Sue Blackwell, Jasmine Lester, Peter R. Gibson, Emma P. Halmos, Zaid Ardalan, Janindra Warusavitarne, Kapil Sahnan, and et al. 2025. "A Quality Assessment and Evaluation of Credible Online Dietary Resources for Patients with an Ileoanal Pouch" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155348

APA StyleRhys-Jones, D. R., Ghersin, I., Argyriou, O., Blackwell, S., Lester, J., Gibson, P. R., Halmos, E. P., Ardalan, Z., Warusavitarne, J., Sahnan, K., Segal, J. P., Hart, A., & Yao, C. K. (2025). A Quality Assessment and Evaluation of Credible Online Dietary Resources for Patients with an Ileoanal Pouch. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155348