Reducing State and Trait Anxiety Through Art Therapy in Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Results from a Pilot Repeated-Measures Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Description of the Art Therapy Intervention

2.2.1. Art Therapy Intervention Description for Replication

2.2.2. Structure of the Sessions

- Opening Phase: Body-centered or symbolic activities were used to promote grounding and facilitate connection between bodily sensations and emotions.

- Art-Making Phase: Creative activities were inspired by the work of contemporary female artists and focused on the use of textile materials to encourage symbolic expression.

- Closing Phase: A group sharing circle allowed participants to reflect on their experience and process emerging emotions within a supportive peer context.

2.2.3. Rationale for Materials and Techniques

2.2.4. Progressive Experiential Content of the Sessions

- Session 1: Participants embroidered a word onto fabric, chosen to represent an aspect of their bodily awareness identified during the opening exercise.

- Session 2: Drawing inspiration from Women Who Run with the Wolves, participants created symbolic “shelter spaces” using collage techniques and recycled fabrics.

- Session 3: A symbolic self-portrait was developed through botanical printing methods on fabric, encouraging reflection on personal identity and embodiment.

- Session 4: Circular mandala compositions were created using tulle, exploring themes of balance, transparency, and interconnectedness. These works were later projected as light installations within the workshop space.

- Session 5: Participants engaged in a reparative exercise, mending a torn canvas with colorful threads, referencing the Japanese philosophy of kintsugi, which values visible repairs as a metaphor for healing and integration of past wounds.

- Session 6: Each participant produced a final textile fragment incorporating key words and images from their personal journey. These fragments were collectively assembled into a large-scale textile manifesto, which was presented in a public exhibition.

2.2.5. Closure and Reflection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

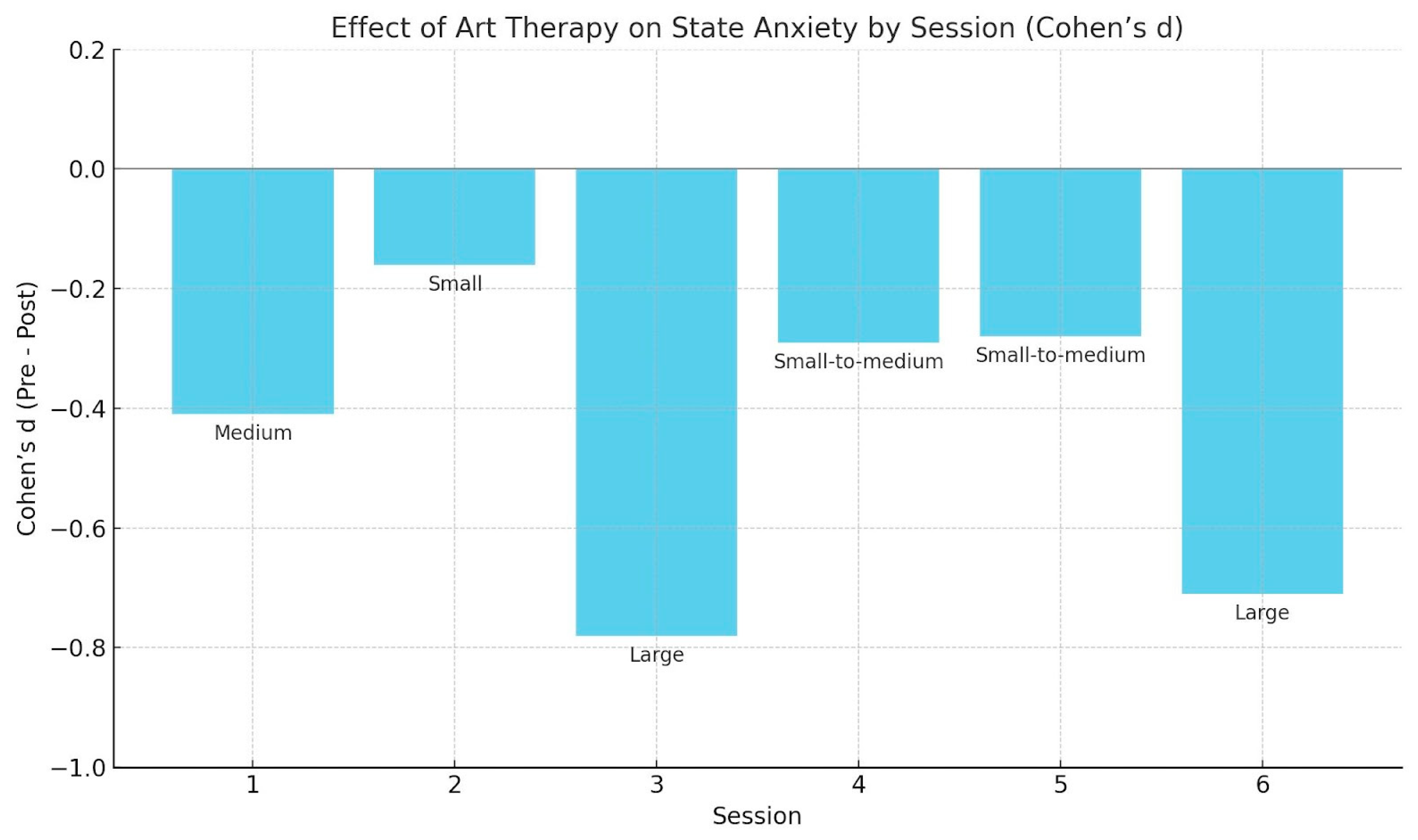

3.1. State Anxiety

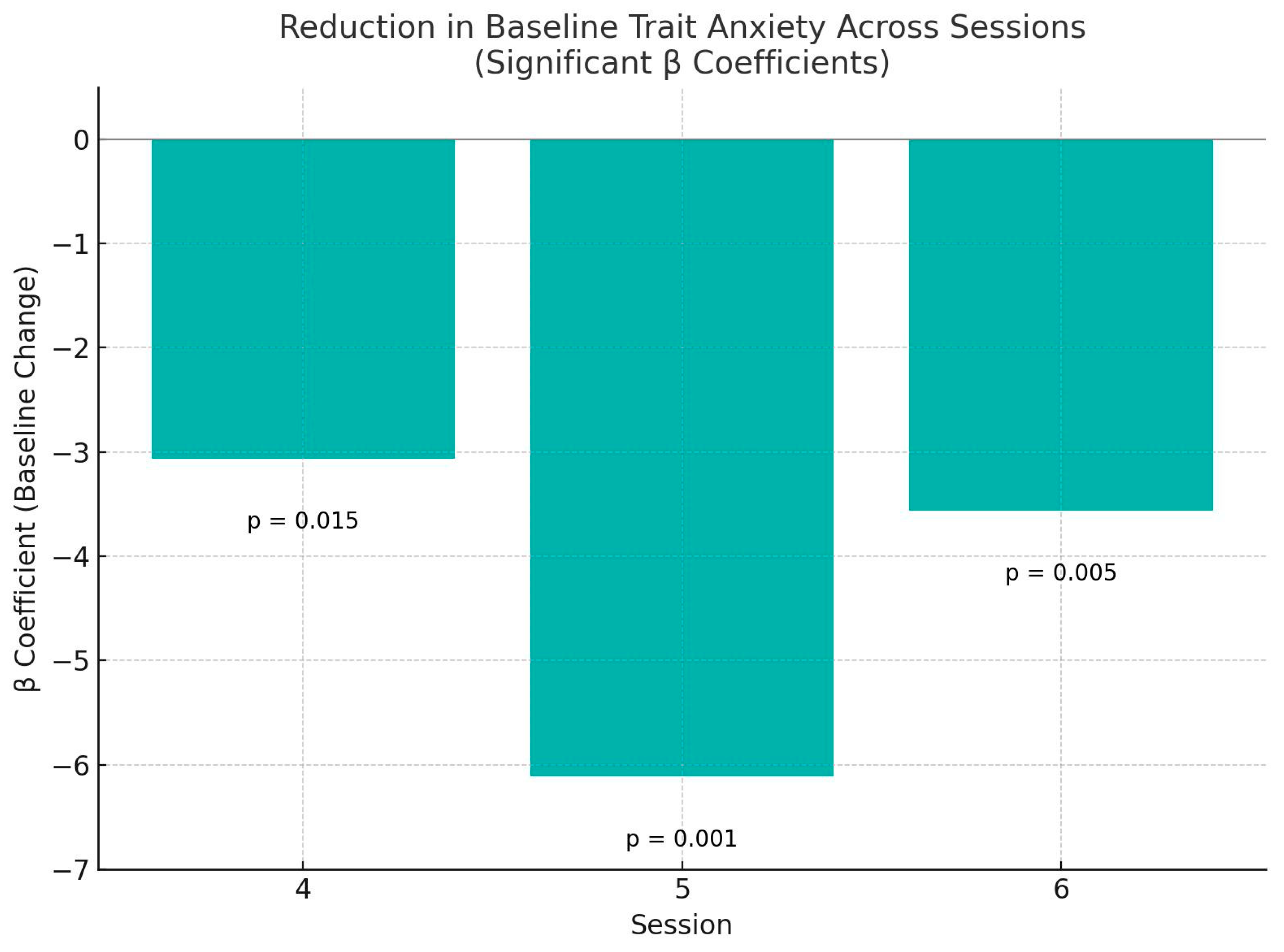

3.2. Trait Anxiety

- Session 4: β = −3.06, p = 0.015

- Session 5: β = −6.11, p < 0.001

- Session 6: β = −3.56, p = 0.005

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, L.; Yu, H.; Xu, J. Art therapy: A complementary treatment for mental disorders. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 686005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.K.G. Art Versus Illness: A Story of Art Therapy; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, E. Art as Therapy with Children; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z.; Shafran, R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, F.; Merizzi, A.; D’Amen, B.; Santini, S. Creativity and art therapies to promote healthy aging: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 906191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, R.; Milnes, D. Art therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, 2, CD003728. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, M.; Reid-Varley, W.B.; Fan, X. Creative art therapy for mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 275, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucharová, M.; Malá, A.; Kantor, J.; Svobodová, Z. Arts therapies interventions and their outcomes in the treatment of eating disorders: Scoping review protocol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.A. The science of the art of psychotherapy. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2012, 18, 467–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Twaddle, S. Anorexia nervosa. BMJ 2007, 334, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairall, L.; Petersen, I.; Zani, B.; Folb, N.; Georgeu-Pepper, D.; Selohilwe, O.; Petrus, R.; Mntambo, N.; Bhana, A.; Lombard, C.; et al. Collaborative care for the detection and management of depression among adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: Study protocol for the CobALT randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018, 19, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeyen, S.; van Hooren, S.; van der Veld, W.M.; Hutschemaekers, G. Measuring the contribution of art therapy in multidisciplinary treatment of personality disorders: The construction of the Self-expression and Emotion Regulation in Art Therapy Scale (SERATS). Personal. Ment. Health 2018, 12, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeyen, S.; Chakhssi, F.; van Hooren, S. Benefits of art therapy in people diagnosed with personality disorders: A quantitative survey. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Choudhari, S.G.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Quazi Syed, Z. Role of art therapy in the promotion of mental health: A critical review. Cureus 2022, 14, e28026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, M.; Kempf, J.K. Art therapy for psychological disorders and mental health. In Foundations of Art Therapy; Rastogi, M., Feldwisch, R.P., Pate, M., Scarce, J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 335–377. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, M.; Orkibi, H.; Zarate, R.; Karkou, V.; Sajnani, N.; Malhotra, B.; Ho, R.T.H.; Kaimal, G.; Baker, F.A.; Koch, S.C. From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 678397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Neuro-vulnerability in energy metabolism regulation: A comprehensive narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C.N.; Spoor, S.; Presnell, K.; Shaw, H. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Zipfel, S.; Micali, N.; Wade, T.; Stice, E.; Claudino, A.M. Eating disorders: Innovation and progress urgently needed. Lancet 2020, 395, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, Y. A practical development protocol for evidence-based digital integrative arts therapy content in public mental health services: Digital transformation of mandala art therapy. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1175093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Pellegrino, F.; Croatto, G.; Carfagno, M.; Hilbert, A.; Treasure, J.; Wade, T.; Bulik, C.M.; Zipfel, S.; Hay, P.; et al. Treatment of eating disorders: A systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 142, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P. Current approach to eating disorders: A clinical update. Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M.E.; McFarlane, T.; Cassin, S. Alexithymia and eating disorders: A critical review of the literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafir, T.; Siegel, E.V.; Titone, D. Symbolic and embodied expression in art therapy: Psychological mechanisms and therapeutic pathways. Art Ther. 2020, 37, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, L.D. Expressive Therapies Continuum: A Framework for Using Art in Therapy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M.; Lynch, J.E. Body image across the life span in adult women: The role of self-objectification. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Handbook of Art Therapy, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Collie, K.; Backos, A.; Malchiodi, C.; Spiegel, D. Art therapy for combat-related PTSD: Recommendations for research and practice. Art Ther. 2006, 23, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, R.A.; Finzi, S.; Veglia, F.; Di Fini, G. Narrative and bodily identity in eating disorders: Toward an integrated theoretical–clinical approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 785004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckmezian, T.; Paxton, S.J. A systematic review of outcomes following residential treatment for eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, L.D. Walking the line between passion and caution: Using the expressive therapies continuum to avoid therapist errors. Art Ther. 2008, 25, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slayton, S.C.; D’Archer, J.; Kaplan, F. Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy: A review of findings. Art Ther. 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, G.; Ray, K. Free art-making in an art therapy open studio: Changes in affect and self-efficacy. Arts Health 2016, 9, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmire, D.A.; Gorham, S.R.; Rankin, N.E.; Grimm, D. The influence of art making on anxiety: A pilot study. Art Ther. 2012, 29, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Abdullah, A. The effects of art therapy interventions on anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinics 2024, 79, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Eren, N.; Tunç, P.; Yücel, B. Effect of a long-term art-based group therapy with eating disorders. Med. Humanit. 2023, 49, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, Y.; Hadar Shoval, D.; Levkovich, I.; Yinon, D.; Gigi, K.; Pen, O.; Angert, T.; Elyoseph, Z. The externalization of internal experiences in psychotherapy through generative artificial intelligence: A theoretical, clinical, and ethical analysis. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1512273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzillo, F.; Gorman, B.S.; De Luca, E.; Faccini, F.; Bush, M.; Silberschatz, G.; Dazzi, N. Preliminary data about the validation of a self-report for the assessment of interpersonal guilt: The Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scales-15s (IGRS-15s). Psychodyn. Psychiatry 2018, 46, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, L.D. Drawing from Within: Using Art to Treat Eating Disorders; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, G.; Ayaz, H.; Herres, J.M.; Dieterich-Hartwell, R.; Makwana, B.; Kaiser, D.H.; Nasser, J.A. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy assessment of reward perception based on visual self-expression: Coloring, doodling, and free drawing. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolwerk, A.; Mack-Andrick, J.; Lang, F.R.; Dörfler, A.; Maihöfner, C. How art changes your brain: Differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, W.; Nonnekes, J.; Rahimi, T.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Bloem, B.R. Dance classes improve self-esteem and quality of life in persons with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 5843–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5–defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocen, O.; Ozturk, C.S. The effect of therapeutic artistic activities on anxiety and psychological well-being in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, M. When the body speaks: The archetypes in the body. J. Anal. Psychol. 2000, 45, 409–423. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, G.; Ray, K.; Muniz, J. Reduction of cortisol levels and participants’ responses following art making. Art Ther. 2016, 33, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, K.S.; Vasiu, F. How the arts heal: A review of the neural mechanisms behind the therapeutic effects of creative arts on mental and physical health. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1422361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Cohen’s d | Effect Size Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | −0.41 | Medium |

| Session 2 | −0.16 | Small |

| Session 3 | −0.78 | Large |

| Session 4 | −0.29 | Small-to-medium |

| Session 5 | −0.28 | Small-to-medium |

| Session 6 | −0.71 | Large |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monaco, F.; Vignapiano, A.; Landi, S.; Panarello, E.; Di Gruttola, B.; Gammella, N.; Adiutori, S.; Acierno, E.; Di Stefano, V.; Pullano, I.; et al. Reducing State and Trait Anxiety Through Art Therapy in Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Results from a Pilot Repeated-Measures Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155298

Monaco F, Vignapiano A, Landi S, Panarello E, Di Gruttola B, Gammella N, Adiutori S, Acierno E, Di Stefano V, Pullano I, et al. Reducing State and Trait Anxiety Through Art Therapy in Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Results from a Pilot Repeated-Measures Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155298

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonaco, Francesco, Annarita Vignapiano, Stefania Landi, Ernesta Panarello, Benedetta Di Gruttola, Naomi Gammella, Silvia Adiutori, Eleonora Acierno, Valeria Di Stefano, Ilaria Pullano, and et al. 2025. "Reducing State and Trait Anxiety Through Art Therapy in Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Results from a Pilot Repeated-Measures Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155298

APA StyleMonaco, F., Vignapiano, A., Landi, S., Panarello, E., Di Gruttola, B., Gammella, N., Adiutori, S., Acierno, E., Di Stefano, V., Pullano, I., Corrivetti, G., & Steardo Jr, L. (2025). Reducing State and Trait Anxiety Through Art Therapy in Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Results from a Pilot Repeated-Measures Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155298