Symptom Burden, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs of Younger Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Content Analysis of ePAQ-Pelvic Floor Free-Text Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

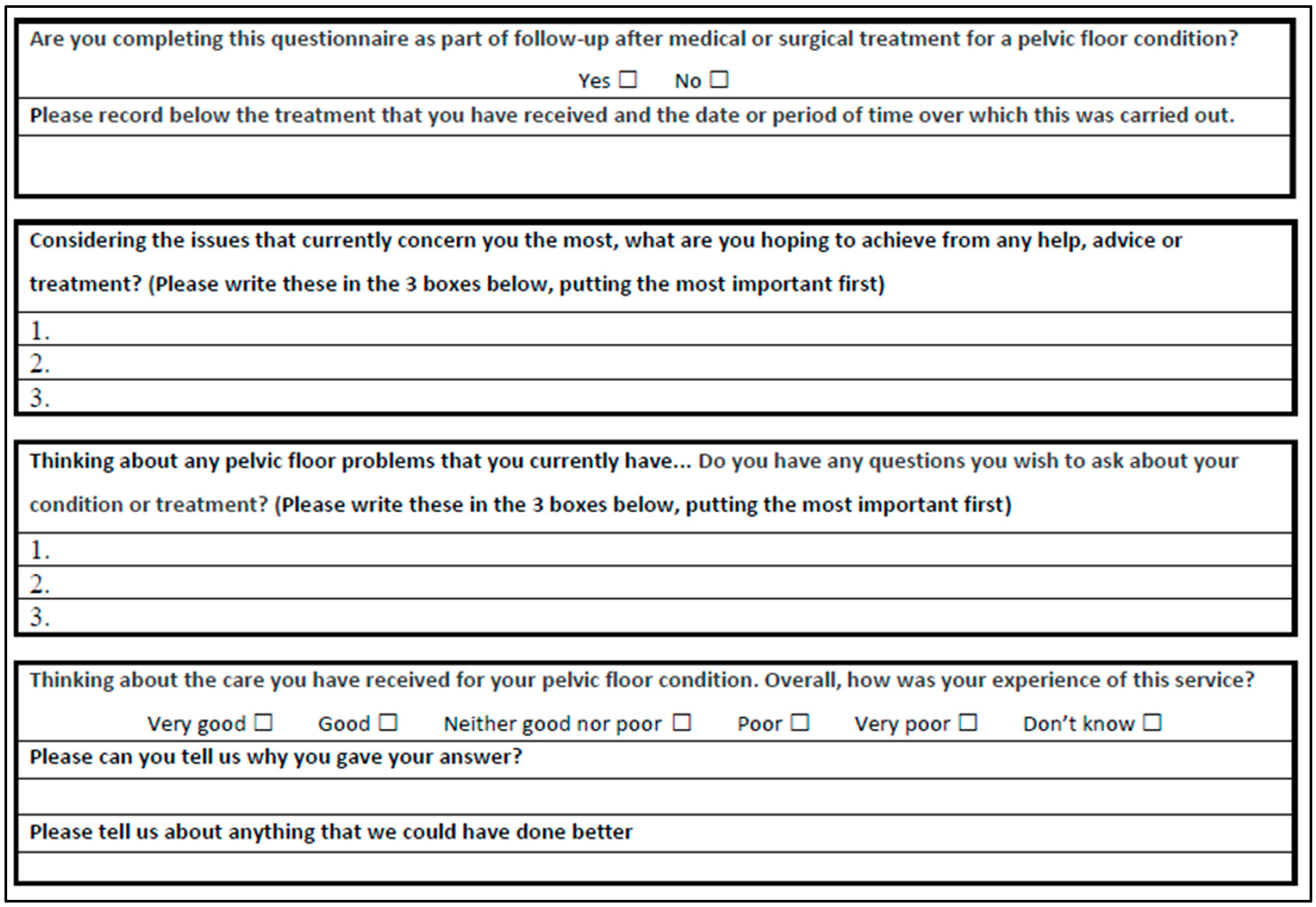

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Summary of the Data and Analytic Approach

2.3. Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

2.4. Sampling

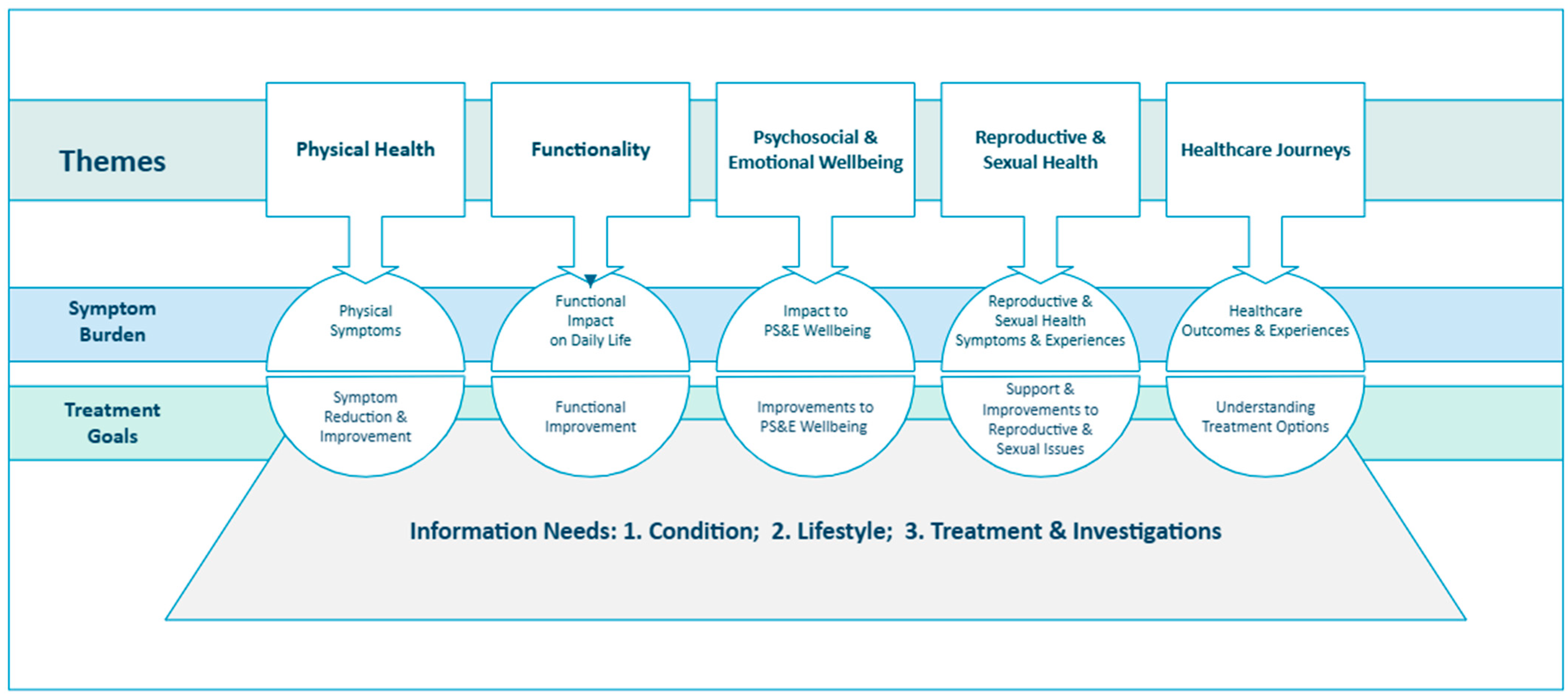

2.5. Analyzing Symptom Impacts, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Researcher Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Severity and Impact of Pelvic Floor Symptoms

3.1.1. Symptom and Quality of Life Domain Scores

3.1.2. Impact Scores

3.2. Symptom Burden, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs of Younger Women

3.2.1. Theme 1: Physical Health

- Symptom Burden: Physical Symptoms

‘Vaginal prolapse and dragging heaviness in abdomen’(age 39)

‘Wind and bowel urgency and incontinence. Bladder incontinence’(age 43)

‘Bowel problems, having to keep taking laxatives as I have been doing for many years’(age 48)

‘The pain makes me feel sick often’(age 39)

- 2.

- Treatment Goals: Symptom Reduction and Improvement

‘Get rid of prolapse so that I can open my bowels without having to support the bowel vaginal wall’(age 45)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Functionality

- Symptom Burden: Functional Impact on Daily Life

‘I kept having excruciating pain in my tummy and vaginal area. I took myself to hospital and a gynecologist said I had a prolapse of the womb, as well as loose skin which hangs down, causing more pain/infections/embarrassment and [difficulties in] the enjoyment of a sex life/social activities/day to day housework/exercise and anything which involves moving around’(age 33)

- 2.

- Treatment Goals: Functional Improvement

‘Help returning to a normal life, i.e., […] walking without pain’(age 28)

‘To find a pessary that works so I can work out again and lift children while keeping pressure off pelvic floor’(age 38)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Psychosocial and Emotional Wellbeing

- Symptom Burden: Impact on Psychosocial and Emotional Wellbeing

‘I’m really depressed about my vagina and how it makes me feel.’(age 23)

‘I have a toddler and 10-year-old, and I can’t even be the mum they deserve’(age 32)

- 2.

- Treatment Goals: Improvements to Psychosocial and Emotional Wellbeing

‘Correction of prolapse […] so I can enjoy dancing (nights out) and confidence, no longer being embarrassed […] stop taking antidepressants’(age 42)

‘Be able to live a more normal life’(age 28)

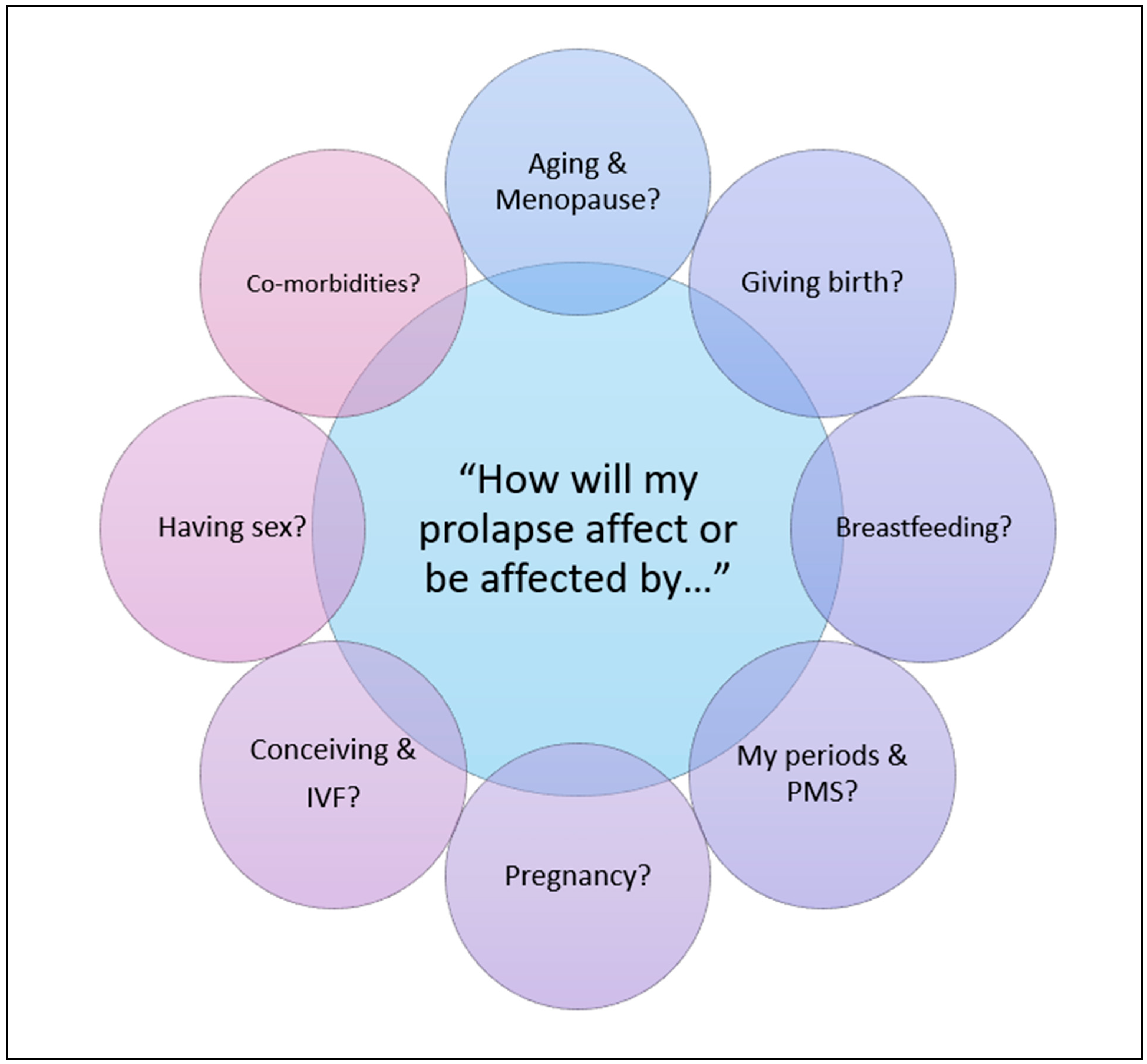

3.2.4. Theme 4: Reproductive and Sexual Health

- Symptom Burden: Reproductive and Sexual Health Symptoms and Experiences

- Impact on Sexual Function and Satisfaction

‘This is serious for me, I can’t meet anyone or be with anyone, because sex is important and I want to have sex with someone and feel sexy, but I just can’t’(age 23)

‘Have to empty my bowel prior to having sex for fear of leakage during sex’(age 45)

- ii.

- Pregnancy and Childbirth Concerns

‘After birth of 2nd child vagina opening is too wide due to stitches coming undone’(age 39)

‘First daughter ventouse (now 9) and second daughter (now 5 years old), forceps which caused the problems’(age 40)

- iii.

- Menstrual/Cyclical Health Concerns

‘Prolapse bulging, inability to keep tampon in’(age 33)

‘My bladder issues are very related to my cycle. What holistically can be done?’(age 41)

- 2.

- Treatment Goals: Support and Improvements to Reproductive and Sexual Issues

- Restoration of Sexual Function and Satisfaction

‘Reduce pain/discomfort during sexual intercourse and regain more enjoyment of sex’(age 36)

‘To be able to have a sex life without embarrassment by being tighter and looking normal externally’(age 39)

- ii.

- Support Relating to Reproductive Health

‘Since I have given birth, my condition has gotten worse, and I have not received any further treatment’(age 26)

‘Relief from pain of episiotomy scar tissue. Possible refashioning which I was due to have [date]. Regain control over my pelvic floor’(age 38)

‘Do I have non-surgical options as considering one more baby at some point?’(age 36)

‘I have no interest in having children biologically, therefore am I eligible for prolapse surgery?’(age 28)

- iii.

- Improved Menstruation Experiences

‘Strengthening pelvic floor to use a menstrual cup again’(age 32)

‘Reduce heavy feeling in vagina when due a period.’(age 47)

3.2.5. Theme 5: Healthcare Journeys

- Symptom Burden: Healthcare Outcomes and Experiences

- Ongoing Treatment Concerns

‘Vaginal ring pessary inserted at appointment as moderate prolapse […] Really suffering with pelvic pain and back ache and anus pressure’(age 35)

‘I had a Rectopexy […] I have now developed superficial dyspareunia to the extent that penetration is completely impossible’(age 50)

- ii.

- Future Treatment Concerns

‘Because I also have a slight rectocele, will my cystocele repair make the rectocele more of a problem?’(age 49)

‘I am only 45 and I have concerns about non-surgical treatment that has to be repeated regularly’(age 45)

- iii.

- Perception of Care

‘I was very apprehensive before attending as it’s a very personal issue. Everyone I met was supportive and understanding and put me at my ease. I feel I received appropriate advice, and the proposed treatment plan is as I hoped.’(age 27)

‘My initial concerns post-op were dismissed, which resulted in emergency surgery. Supposed to have follow-up or response via PALS. Not had post-op meeting with head of gynecology’(age 46)

- 2.

- Treatment Goals: Understanding Treatment Options

‘How can I go about trying other pessaries (ring pessary has not worked for me)’(age 38)

‘I don’t want that mesh thing that causes horrible pain and infection!’(age 49)

3.2.6. Theme 6: Information Needs

- Condition-Specific Information Needs

‘Is it a cystocele or rectocele or both?’(age 33)

‘Advice on how sex could be less painful because of tightness and dryness’(age 32)

‘What has caused this prolapse? i.e., can I change something I am doing to stop it getting any worse?’(age 25)

‘Will my prolapse worsen with menopause?’(age 34)

‘To know how to manage periods following changes to cervix and vaginal wall’(age 33)

‘Will future pregnancies affect my prolapse? Will I be able to have another natural birth?’(age 26)

- 2.

- Lifestyle Information Needs

‘What can I do to help myself (I know I need to lose weight)?’(age 38)

‘Is swimming or any activity like that bad for the prolapse? Could it lead to infection?’(age 40)

- 3.

- Treatment and Investigations

- i.

- Treatment Eligibility and Options

‘What are the treatment options available’(age 33)

‘At what point would surgical management be considered for my cystocele?’(age 40)

- ii.

- Diagnostic and Intervention Processes

‘Can you examine me both standing and lying and what difference does that make to prolapse grade?’(age 38)

‘Is the operation open surgery? Don’t want laparoscopic surgery as hernia risk is higher’(age 48)

- iii.

- Navigation of Healthcare Systems

‘Is my problem difficult? Does it need a long treatment journey?’(age 33)

‘Can I be treated under NHS umbrella, I mean not in private clinic?’(age 35)

- iv.

- Expectations, Risks, and Recovery

‘Will I need to rest? Will my partner have to take time of work? Will I be in pain?’(age 31)

‘What are the recovery times, and will I be continent?’(age 48)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ePAQ-PF | electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire—Pelvic Floor |

| POP | Pelvic organ prolapse |

| PPI | Patient and Public Involvement |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| NHS | National Health Service (UK) |

Appendix A

- Symptom Burden—Key issues and illustrative quotes

- Treatment Goals—Key issues and illustrative quotes

- Information Needs—Key issues and illustrative quotes

| Theme | Symptom Burden | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Physical Health | Physical symptoms | ‘Prolapse is hanging out all the time’ (age 39) ‘Constant irritation in my vagina’ (age 40) ‘Pain, bloating and continuous discomfort in my abdomen and back’ (age 47) ‘Prolapse in my bottom is affecting me when I go to the toilet’ (age 36) ‘Vaginal prolapse and dragging heaviness in abdomen’ (age 39) ‘Wind and bowel urgency and incontinence. Bladder incontinence’ (age 43) ‘Bowel problems, having to keep taking laxatives as I have been doing for many years’ (age 48) ‘The pain makes me feel sick often’ (age 39) |

| Theme 2: Functionality | Functional impact on daily life | ‘Avoiding exercise for fear of long-term damage/incontinence’ (age 36) ‘Ring pessary inserted in May. Not helped, various sizes tried as unable to walk a short distance even with the pessary’ (age 45) ‘My prolapse is always out of my vagina. It’s very uncomfortable and sore and stings a lot of the time when I’m working’ (age 50) ‘I kept having excruciating pain in my tummy and vaginal area. I took myself to hospital and a gynaecologist said I had a prolapse of the womb, as well as loose skin which hangs down, causing more pain/infections/embarrassment and [difficulties in] the enjoyment of a sex life/social activities/day to day housework/exercise and anything which involves moving around’ (age 33) |

| Theme 3: Psychosocial & Emotional Wellbeing | Impact to psychosocial & emotional wellbeing | ‘I’m really depressed about my vagina and how it makes me feel.’ (age 23) ‘I have lost my sex life and nearly my marriage after the depression this has caused.’ (age 46) ‘Feel more attractive again […] My mental health is not good due to this’ (age 42) ‘I have a toddler and 10-year-old, and I can’t even be the mum they deserve’ (age 32) |

| Theme 4: Reproductive & Sexual Health | Impact to sexual function & satisfaction | ‘Currently not having sex due to prolapse’ (age 41) ‘Swelling of vagina after sex’ (age 26) ‘This is serious for me, I can’t meet anyone or be with anyone, because sex is important and I want to have sex with someone and feel sexy, but I just can’t’ (age 23) ‘Have to empty my bowel prior to having sex for fear of leakage during sex’ (age 45) |

| Pregnancy & childbirth concerns | ‘Has my child done damage which has gone unnoticed?’ (age 31) ‘After birth of 2nd child vagina opening is too wide due to stitches coming undone’ (age 39) ‘First daughter ventouse (now 9) and second daughter (now 5 years old), forceps which caused the problems’ (age 40) | |

| Menstrual/cyclical health concerns | ‘Prolapse bulging, inability to keep tampon in’ (age 33) ‘To discuss why using tampons leads to left-sided moderate to severe lower abdominal pain’ (age 41) ‘My bladder issues are very related to my cycle. What holistically can be done?’ (age 41) | |

| Theme 5: Healthcare Journeys | Ongoing treatment concerns | ‘Vaginal ring pessary inserted at appointment as moderate prolapse […] Really suffering with pelvic pain and back ache and anus pressure’ (age 35) ‘‘Why can’t I wee when I don’t have antibiotics, yet I can only when I am on them’ (age 32) ‘I had a Rectopexy […] I have now developed superficial dyspareunia to the extent that penetration is completely impossible’ (age 50) |

| Future treatment concerns | ‘Because I also have a slight rectocele, will my cystocele repair make the rectocele more of a problem?’ (age 49) ‘I am only 45 and I have concerns about non-surgical treatment that has to be repeated regularly’ (age 45) | |

| Perceptions of care | ‘I was very apprehensive before attending as it’s a very personal issue. Everyone I met was supportive and understanding and put me at my ease. I feel I received appropriate advice, and the proposed treatment plan is as I hoped.’ (age 27) ‘[Healthcare professional] on the ward was very kind and matter of fact which made me feel more comfortable about what is an uncomfortable issue.’ (age 43) ‘Treatment been poor, feel consultant covering up. The gynae department is known not to be up to standard […] there are a lot of problems, and they have let me down badly.’ (age 49) ‘My initial concerns post-op were dismissed which resulted in emergency surgery. Supposed to have follow up or response via PALS. Not had post-op meeting with head of gynaecology’ (age 46) ‘I feel that I have been forced to suffer and put at great physical risk by red tape that delayed the whole process’ (age 41) |

| Theme | Treatment Goal | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Physical Health | Symptom reduction & improvement - prolapse, urinary, bowel, vaginal and gastro-intestinal symptoms | ‘Not to have to wear pads and sneeze, cough, laugh without leaking.’ (age 30) ‘To sort my prolapse so that I can empty my bowels like a normal person.’ (age 50) ‘No dragging or feeling like everything is falling out down below.’ (age 36) ‘No bulging into my vagina as it feels horrid.’ (age 34) ‘Ease bloating.’ (age 47) ‘Get rid of prolapse so that I can open my bowels without having to support the bowel vaginal wall’ (age 45) |

| Symptom reduction & improvement - pain/discomfort | ‘Help ease constant discomfort.’ (age 34) ‘I hope to have less abdominal pain and discomfort because I suffer every day from abdominal issues.’ (age 32) ‘Improve pain management of prolapse in terms of general dragging pain, plus soreness and abrasion.’ (age 37) | |

| Management of other gynaecological Health concerns | ‘Polycystic ovaries gone.’ (age 43) ‘Sort prolapse and fibroids to see what’s causing abdominal pain.’ (age 50) | |

| Theme 2: Functionality | Functional improvement - work life | ‘To be able to work […] and live my life without my uterus hanging in my knickers.’ (age 41) ‘[To] feel confident in work and social circumstances.’ (age 50) ‘Being able to do my job without having to worry about prolapse and leakage.’ (age 49) |

| Functional improvement - ability to engage in daily activities | ‘Housework/childcare without being limited by vaginal prolapse.’ (age 40) ‘Resume regular day to day activities.’ (age 38) | |

| Functional improvement - mobility & exercise | ‘Be able to do exercise I enjoy.’ (age 30) ‘To be able to exercise without worry of further damage.’ (age 49) ‘To run around after my children without fear of leaking.’ (age 30) ‘I need to be able to run and play with my children.’ ‘Help returning to a normal life, i.e., […] walking without pain’ (age 28) ‘To find a pessary that works so I can work out again and lift children whilst keeping pressure off pelvic floor’ (age 38) | |

| Theme 3: Psychosocial & Emotional Wellbeing | Stronger social and family relationships | ‘Be able to spend more time with family and friends.’ (age 28) ‘Self-confidence with my husband.’ (age 36) ‘Be the wife and mum I felt I was failing so miserably at.’ (age 35) |

| Improved mental health and positive self-image | ‘Wish to achieve confidence, self-esteem.’ (age 26) ‘I’d like a normal looking vagina […] I’d like my confidence back.’ (age 39) ‘[To] not feel so disgusting all the time.’ (age 32) ‘To improve my life, to help me socialise and decrease depression from isolation’ (age 48) ‘Correction of prolapse […] so I can enjoy dancing (nights out) and confidence, no longer being embarrassed […] stop taking antidepressants’ (age 42) | |

| Enhanced quality of life | ‘To get back to normal everyday life.’ (age 30) ‘To please give me my life back.’ (age 46) ‘Better quality of life. Increase in health.’ (age 49) ‘Be able to live a more normal life’ (age 28) | |

| Theme 4: Reproductive & Sexual Health | Restoration of sexual function and satisfaction | ‘Improve vaginal sensation during sex.’ (age 36) ‘To be able to have a sexual relationship.’ (age 46) ‘Reduce pain/discomfort during sexual intercourse & regain more enjoyment of sex.’ (age 36) ‘To be able to have a sex life without embarrassment by being tighter and looking normal externally’ (age 39) |

| Support relating to reproductive health | ‘We would like another child safely.’ (age 37) ‘[To] be able to get pregnant in the near future.’ (age 35) ‘Since I have given birth, my condition has gotten worse, and I have not received any further treatment’ (age 26) ‘Relief from pain of episiotomy scar tissue. Possible refashioning which I was due to have [date]. Regain control over my pelvic floor’ (age 38) ‘Do I have non-surgical options as considering one more baby at some point?’ (age 36) ‘I have no interest in having children biologically, therefore am I eligible for prolapse surgery?’ (age 28) | |

| Support relating to contraception | ‘Would the coil help?’ (age 41) ‘Sterilisation to prevent further pregnancy.’ (age 27) ‘Can I be sterilised and will it help?’ (age 42) | |

| Improved menstruation experiences | ‘To be able to comfortably wear a tampon.’ (age 30) ‘Reduce heavy feeling in vagina when due a period.’ (age 47) ‘Irregular bleeding to be resolved.’ (age 30) ‘Strengthening pelvic floor to use a menstrual cup again’ (age 32) ‘How can I improve my PMS and heavy periods?’ (age 39) ‘To be able to wear tampons without them falling out’ (age 40) | |

| Theme 5: Healthcare Journeys | Exploring & understanding treatment options | ‘To be timely offered the relevant intervention aimed to resolve the problem (prolapse).’ (age 46) ‘Discuss everything including past surgeries diagnosis and prognosis.’ (age 43) ‘Consider different pessaries and if oestrogen cream is an option.’ (age 37) ‘How can I go about trying other pessaries (ring pessary has not worked for me)’ (age 38) ‘I don’t want that mesh thing that causes horrible pain and infection!’ (age 49) ‘Can you please do this operation so I can start living again as for 2 years I have had hell.’ (age 46) |

| Theme | Information Needs | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 6: Information Needs | Condition-specific information needs | ‘Is it a cystocele or rectocele or both?’ (age 33) ‘How severe are my symptoms?’ (age 38) ‘Advice on how sex could be less painful because of tightness and dryness’ (age 32) ‘Is the bulge from my rectum into my vagina during bowel movements likely to get worse?’ (age 40) ‘What has caused this prolapse? i.e., can I change something I am doing to stop it getting any worse?’ (age 25) ‘Will my prolapse worsen with menopause?’ (age 34) ‘To know how to manage periods following changes to cervix and vaginal wall’ (age 33) ‘Will future pregnancies affect my prolapse? Will I be able to have another natural birth?’ (age 26) ‘Will it interfere with future IVF treatment?’ (age 33) ‘Can this affect me being able to conceive again?’ (age 40) |

| Lifestyle information needs | ‘What can I do to help myself (I know I need to lose weight)?’ (age 38) ‘Can I improve my urge incontinence when exercising?’ (age 39) ‘What exercise can I do now without making my condition worse? (age 41) ‘Is swimming or any activity like that bad for the prolapse? Could it lead to infection?’ (age 40) | |

| Treatment eligibility & options | ‘What are the treatment options available’ (age 33) ‘At what point would surgical management be considered for my cystocele?’ (age 40) ‘Psychosexual counselling, is this still available?’ (age 36) ‘Can you opt for surgery straight out or do you have to try the other options first’ (age 49) | |

| Diagnostic & intervention processes | ‘Can you examine me both standing and lying and what difference does that make to prolapse grade?’ (age 38) ‘Will more be done to try and find the reason behind my chronic stomach pains and discomfort?’ (age 32) ‘Is it day surgery or overnight stay if having operation?’ (age 42) ‘Is the operation open surgery? Don’t want laparoscopic surgery as hernia risk is higher’ (age 48) | |

| Navigation of healthcare systems | ‘What is the next process and how long is the wait’ (age 39) ‘Time frames for potential solutions? how long are the treatments?’ (age 30) ‘Is my problem difficult? Does it need a long treatment journey?’ (age 33) ‘Can I be treated under NHS umbrella, I mean not in private clinic?’ (age 35) | |

| Expectations, risks & recovery | ‘Will I need to rest? Will my partner have to take time of work? Will I be on pain?’ (age 31) ‘What are the recovery times, and will I be continent?’ (age 48) ‘Will surgery put me at increased risk of scarring inside my vagina so risking reduced sensation’ (age 37) |

References

- Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Xue, L.; Zhu, Q.; Gao, X.; Wu, M. Global Burden and Trends of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Associated with Aging Women: An Observational Trend Study from 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 975829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, H.P. Prolapse Worsens with Age, Doesn’t It? Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 48, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, R.; Hess, R.; Biddington, C.; Federico, M. Association of Lean Body Mass to Menopausal Symptoms: The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. Women’s Midlife Health 2020, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M.; Vaughan, C.P.; Goode, P.S.; Redden, D.T.; Burgio, K.L.; Richter, H.E.; Markland, A.D. Prevalence and Trends of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in U.S. Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alperin, M.; Burnett, L.; Lukacz, E.; Brubaker, L. The Mysteries of Menopause and Urogynecologic Health: Clinical and Scientific Gaps. Menopause 2019, 26, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, L.; O’Sullivan, C.; Doody, C.; Perrotta, C.; Fullen, B. Pelvic Organ Prolapse: The Lived Experience. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, M.D.; Maher, C. Epidemiology and Outcome Assessment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 1783–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toye, F.; Pearl, J.; Vincent, K.; Barker, K. A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis Using Meta-Ethnography to Understand the Experience of Living with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2631–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada, M.P.; Jones, S.; Falconi, G.; Milhem Haddad, J.; Betschart, C.; Pergialiotis, V.; Doumouchtsis, S.K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies on Pelvic Organ Prolapse for the Development of Core Outcome Sets. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2020, 39, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari, Z.; Ghaemi, M.; Shafiee, A.; Jelodarian, P.; Hosseini, R.S.; Pouyamoghaddam, S.; Montazeri, A. Quality of Life Following Pelvic Organ Prolapse Treatments in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelovsek, J.E.; Barber, M.D. Women Seeking Treatment for Advanced Pelvic Organ Prolapse Have Decreased Body Image and Quality of Life. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghetti, C.; Skoczylas, L.C.; Oliphant, S.S.; Nikolajski, C.; Lowder, J.L. The Emotional Burden of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women Seeking Treatment: A Qualitative Study. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 21, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinman, C.L.; Lemieux, C.A.; Agrawal, A.; Gaskins, J.T.; Meriwether, K.V.; Francis, S.L. The Relationship between Age and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Bother. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 28, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlin, G.L.; Jiménez, J.H.; Lange, S.; Heinzl, F.; Koch, M.; Umek, W.; Bodner-Adler, B. Impact on Sexual Function and Wish for Subsequent Pregnancy after Uterus-Preserving Prolapse Surgery in Premenopausal Women. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS Choices. Overview—Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pelvic-organ-prolapse/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Gjerde, J.L.; Rortveit, G.; Muleta, M.; Adefris, M.; Blystad, A. Living with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Voices of Women from Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 28, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskayne, K.; Willars, J.; Pitchforth, E.; Tincello, D.G. Women’s Expectations of Prolapse Surgery: A Retrospective Qualitative Study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2013, 33, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirskaya, M.; Isaksson, A.; Lindgren, E.-C.; Carlsson, I.-M. Bearing the Burden of Spill-over Effects: Living with a Woman Affected by Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse after Vaginal Birth—From a Partner’s Perspective. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2023, 37, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadizadeh-Talasaz, Z.; Khadivzadeh, T.; Ebrahimipour, H.; Khadem Ghaebi, N. The Experiences of Women Who Live with Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2021, 9, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjerde, J.L.; Rortveit, G.; Adefris, M.; Belayneh, T.; Blystad, A. Life after Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery: A Qualitative Study in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, T.S.; Savitri, R.; Bhavani, A. Women’s Experiences of Utero-Vaginal Prolapse: A Qualitative Study from Tamil Nadu, India. 1999. Available online: https://www.ruwsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/41.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Lowder, J.L.; Ghetti, C.; Nikolajski, C.; Oliphant, S.S.; Zyczynski, H.M. Body Image Perceptions in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 441.e1–441.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjerde, J.L.; Rortveit, G.; Adefris, M.; Mekonnen, H.; Belayneh, T.; Blystad, A. The Lucky Ones Get Cured: Health Care Seeking among Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dell, K.K.; Jacelon, C.S. Not the Surgery for a Young Person: Women’s Experience with Vaginal Closure Surgery for Severe Prolapse. Urol. Nurs. 2005, 25, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abhyankar, P.; Uny, I.; Semple, K.; Wane, S.; Hagen, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Guerrero, K.; Tincello, D.; Duncan, E.; Calveley, E.; et al. Women’s Experiences of Receiving Care for Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Qualitative Study. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, A.-M.; Thakar, R.; Sultan, A.H.; Burger, C.W.; Paulus, A.T.G. Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Women’s Sexual Concerns Unraveled. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, L.; O’Sullivan, C.; Doody, C.; Perrotta, C.; Fullen, B.M. Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Women’s Experiences of Accessing Care & Recommendations for Improvement. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedel, A.; Tegerstedt, G.; Maehle-Schmidt, M.; Nyrén, O.; Hammarström, M. Symptoms and Pelvic Support Defects in Specific Compartments. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergeldt, T.F.M.; Weemhoff, M.; IntHout, J.; Kluivers, K.B. Risk Factors for Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Its Recurrence: A Systematic Review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 26, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, V.L.; Blomquist, J.L.; Knoepp, L.R.; Hoskey, K.A.; McDermott, K.C.; Muñoz, A. Pelvic Floor Disorders 5–10 Years after Vaginal or Cesarean Childbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 118, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLancey, J. The Appearance of Levator Ani Muscle Abnormalities in Magnetic Resonance Images after Vaginal Delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 101, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Pelvic Organ Prolapse|RCOG. Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/for-the-public/browse-our-patient-information/pelvic-organ-prolapse/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Lallemant, M.; Clermont-Hama, Y.; Giraudet, G.; Rubod, C.; Delplanque, S.; Kerbage, Y.; Cosson, M. Long-Term Outcomes after Pelvic Organ Prolapse Repair in Young Women. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A.; Toong, P.J.; Kearney, R.; Hagen, S.; McPeake, J. Systematic Review of Evidence for Conservative Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Younger Women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2024, 36, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, L.C.; Tran, M.C.; Davidson, E.R.W.; Walters, M.D.; Ferrando, C.A. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Recurrence in Young Women Undergoing Vaginal and Abdominal Colpopexy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 31, 2661–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Løwenstein, E.; Møller, L.A.; Laigaard, J.; Gimbel, H. Reoperation for Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Danish Cohort Study with 15–20 Years’ Follow-Up. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 29, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, J.L.; Weber, A.M.; Meyn, L.A.; Walters, M.D. Risk Factors for Prolapse Recurrence after Vaginal Repair. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1533–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulten, S.F.; Claas-Quax, M.J.; Weemhoff, M.; van Eijndhoven, H.W.; van Leijsen, S.A.; Vergeldt, T.F.; IntHout, J.; Kluivers, K.B. Risk Factors for Primary Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Prolapse Recurrence: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Itza, I.; Aizpitarte, I.; Becerro, A. Risk Factors for the Recurrence of Pelvic Organ Prolapse after Vaginal Surgery: A Review at 5 Years after Surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2007, 18, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, M.; Wise, B.; Duckett, J. A Qualitative Study of Women’s Preferences for Treatment of Pelvic Floor Disorders. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010, 118, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkadry, E.A.; Kenton, K.S.; FitzGerald, M.P.; Shott, S.; Brubaker, L. Patient-Selected Goals: A New Perspective on Surgical Outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komesu, Y.M.; Rogers, R.G.; Rode, M.A.; Craig, E.C.; Schrader, R.M.; Gallegos, K.A.; Villareal, B. Patient-Selected Goal Attainment for Pessary Wearers: What Is the Clinical Relevance? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 577.e1–577.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hullfish, K.L.; Bovbjerg, V.E.; Gurka, M.J.; Steers, W.D. Surgical versus Nonsurgical Treatment of Women with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Patient Centered Goals at 1 Year. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 2280–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikrishna, S.; Robinson, D.; Cardozo, L.; Cartwright, R. Experiences and Expectations of Women with Urogenital Prolapse: A Quantitative and Qualitative Exploration. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 115, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikrishna, S.; Robinson, D.; Cardozo, L. Qualifying a Quantitative Approach to Women’s Expectations of Continence Surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, T.; Strickland, S.; Pooranawattanakul, S.; Li, W.; Campbell, P.; Jones, G.; Radley, S. What Are the Concerns and Goals of Women Attending a Urogynaecology Clinic? Content Analysis of Free-Text Data from an Electronic Pelvic Floor Assessment Questionnaire (EPAQ-PF). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Nyhof, B.B.; Dunn, S.; Grace, S.L.; Green, C.; Stewart, D.E.; Wright, F.C. How Is Patient-Centred Care Conceptualized in Women’s Health: A Scoping Review. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckay, E.R.; Lundsberg, L.S.; Miller, D.T.; Draper, A.; Chao, J.; Yeh, J.; Rangi, S.; Torres, P.; Stoltzman, M.; Guess, M.K. Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders in Obstetrics. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 25, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Service (NHS). Pelvic Organ Prolapse—Treatment. 2017. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pelvic-organ-prolapse/treatment/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Surgery for Uterine Prolapse Patient Decision Aid? 2019. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123/resources/surgery-for-uterine-prolapse-patient-decision-aid-pdf-6725286112 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Surgery for Vaginal Vault Prolapse Patient Decision Aid? 2019. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123/resources/surgery-for-vaginal-vault-prolapse-patient-decision-aid-pdf-6725286114 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Chen, C.C.G.; Cox, J.T.; Yuan, C.; Thomaier, L.; Dutta, S. Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders in Women Seeking Primary Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Social Care (UK). Women’s Health Strategy for England. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/womens-health-strategy-for-england/womens-health-strategy-for-england#information-and-awareness (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Zapantis, G.; Santoro, N. The Menopausal Transition: Characteristics and Management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 17, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triebner, K.; Johannessen, A.; Svanes, C.; Leynaert, B.; Benediktsdóttir, B.; Demoly, P.; Dharmage, S.C.; Franklin, K.A.; Heinrich, J.; Holm, M.; et al. Describing the Status of Reproductive Ageing Simply and Precisely: A Reproductive Ageing Score Based on Three Questions and Validated with Hormone Levels. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dulmen, S.A.; Lukersmith, S.; Muxlow, J.; Santa Mina, E.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; van der Wees, P.J. Supporting a Person-Centred Approach in Clinical Guidelines. A Position Paper of the Allied Health Community—Guidelines International Network (G-I-N). Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2015, 18, 1543–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, D.T.; Halligan, P.W. The Biopsychosocial Model of Illness: A Model Whose Time Has Come. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghmaian, R.; Miller Smedema, S. A Feminist, Biopsychosocial Subjective Well-Being Framework for Women with Fibromyalgia. Rehabil. Psychol. 2018, 64, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M. Towards a Framework for Women’s Health. Patient Educ. Couns. 1998, 33, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ePAQ.co.uk. The Case for ePAQ-PF: A Summary of Potential Applications and Benefits of Using ePAQ-PF in Women’s Health. 2016. Available online: http://epaq.co.uk/Home/GandO (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Radley, S.; Jones, G.T.; Tanguy, E.; Stevens, V.; Nelson, C.; Mathers, N. Computer Interviewing in Urogynaecology: Concept, Development and Psychometric Testing of an Electronic Pelvic Floor Assessment Questionnaire in Primary and Secondary Care. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 113, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, S.M.; Gangnon, R.E.; Chewning, B.; Wald, A. Increasing Discussion Rates of Incontinence in Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulchandani, S.; Toozs-Hobson, P.; Parsons, M.; McCooty, S.; Perkins, K.; Latthe, P. Effect of Anticholinergics on the Overactive Bladder and Bowel Domain of the Electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire (EPAQ). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2014, 26, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.L.; Radley, S.C.; Lumb, J.; Jha, S. Electronic Pelvic Floor Symptoms Assessment: Tests of Data Quality of EPAQ-PF. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2008, 19, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.L.; Radley, S.C.; Lumb, J.; Farkas, A. Responsiveness of the Electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire-Pelvic Floor (EPAQ-PF). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, A.; Jones, G.; Wood, H.; Sidhu, H. Understanding Women’s Experiences of Electronic Interviewing during the Clinical Episode in Urogynaecology: A Qualitative Study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scurr, K.; Gray, T.G.; Jones, G.L.; Radley, S.C. Development and Initial Psychometric Testing of a Body-Image Domain within an Electronic Pelvic Floor Questionnaire (EPAQ-Pelvic Floor). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. Content Analysis: Method, Applications, and Issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.L. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Guide to Paths Not Taken. Qual. Health Res. 1993, 3, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M. Classical Content Analysis: A Review. In Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound—A Handbook; Bauer, M., Gaskell, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2000; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. In A Companion to Qualitative Research; Flick, U., Kardorff, E.V., Steinke, I., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A Hands-on Guide to Doing Content Analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flick, U. Introduction to Qualitative Research, 7th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, J.; Damschroder, L. Qualitative Content Analysis. Empir. Methods Bioeth. Primer 2007, 11, 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, R.; Salvatore, S.; Khullar, V.; Chapple, C.; Taithongchai, A.; Uren, A.; Abrams, P.; Wein, A. Do We Have the Evidence to Produce Tools to Enable the Identification and Personalization of Management of Women’s Pelvic Floor Health Disorders through the Perinatal and Perimenopausal Periods? ICI-RS 2024. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2025, 44, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szatmári, É.; Makai, A.; Prémusz, É.; Balla, B.J.; Ambrus, E.; Boros-Balint, I.; Ács, P.; Hock, M. Hungarian Women’s Health Care Seeking Behavior and Knowledge of Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Cross-Sectional Study. Urogynecology 2023, 29, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Aged ≤50 Years (n = 399) | Aged >50 Years (n = 1074) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD): 40.9 (6.6) Range: 22–50 | Mean (SD): 66.0 (9.0) Range: 51–90 |

| Number of children | Median (IQR): 2 (2–3) Range: 0–9 | Median (IQR): 2 (2–3) Range: 0–10 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Mean (SD): 27.2 (5.5) Range: 16–53 | Mean (SD): 27.1 (5.1) Range: 14–66 |

| Domain Score 1 | Aged ≤50 Years Median (IQR) | Aged >50 Years Median (IQR) | p-Value | Significant at p = 0.0025 | Higher Overall Score (Median and IQR) | Effect Size (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain and Sensation—Urinary | 11.1 (0.0–33.3) | 11.1 (0.0–22.2) | 0.153 | No | Not significant | 0.037 |

| Voiding—Urinary | 16.7 (8.3–33.3) | 16.7 (8.3–33.3) | 0.903 | No | Not significant | 0.003 |

| Overactive—Bladder | 20.0 (13.3–40.0) | 26.7 (13.3–40.0) | <0.001 | Yes | >50 years | 0.087 |

| Stress Urinary Incontinence | 26.7 (6.7–46.7) | 20.0 (0.0–33.3) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.150 |

| QoL—Urinary | 33.3 (11.1–66.7) | 22.2 (11.1–55.6) | 0.002 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.080 |

| Irritable Bowel | 26.7 (13.3–46.7) | 20.0 (6.7–33.3) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.170 |

| Constipation | 22.2 (11.1–44.4) | 11.1 (11.1–33.3) | 0.002 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.079 |

| Evacuation—Bowel | 19.1 (9.5–38.1) | 14.3 (0.0–23.8) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.175 |

| Continence—Bowel | 9.5 (0.0–23.8) | 9.5 (0.0–23.8) | 0.858 | No | Not significant | 0.005 |

| QoL—Bowel | 11.1 (0.0–44.4) | 0.0 (0.0–33.3) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.138 |

| Body Image | 33.3 (8.3–66.7) | 0.0 (0.0–25.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.311 |

| Pain and Sensation—Vagina | 25.0 (16.7–41.7) | 16.7 (8.3–35.4) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.154 |

| Capacity—Vagina | 0.0 (0.0–11.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.008 | No | ≤50 years | 0.069 |

| Prolapse | 50.0 (25.0–75.0) | 41.7 (16.7–66.7) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.112 |

| QoL—Vagina | 44.4 (22.2–77.8) | 22.2 (11.1–66.7) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.175 |

| Sex and Urinary | 25.0 (0.0–58.3) | 0.0 (0.0–33.3) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.236 |

| Sex and Bowel | 0.0 (0.0–33.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.244 |

| Sex and Vagina | 41.7 (16.7–66.7) | 0.0 (0.0–41.7) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.315 |

| Dyspareunia | 26.7 (13.3–46.7) | 0.0 (0.0–26.7) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.348 |

| General Sex Life | 50.0 (25.0–75.0) | 16.7 (0.0–50.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.331 |

| Impact Score 1 | Aged ≤50 Years Median (IQR) | Aged >50 Years Median (IQR) | p-Value | Significant at p = 0.0029 | Higher Overall Score (Median and IQR) | Effect Size (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain and Sensation—Urinary | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.228 | No | Not significant | 0.031 |

| Voiding—Urinary | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.009 | No | Not significant | 0.068 |

| Overactive Bladder | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.75–2.0) | 0.027 | No | Not significant | 0.058 |

| Stress Urinary Incontinence | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.162 |

| Irritable Bowel | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 | Yes | Equal | 0.132 |

| Constipation | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.126 |

| Evacuation—Bowel | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.211 |

| Continence—Bowel | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.047 | No | Not significant | 0.052 |

| Body Image | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.311 |

| Pain and Sensation—Vagina | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.236 |

| Capacity—Vagina | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.084 |

| Prolapse | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.197 |

| Sex and Urinary | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.274 |

| Sex and Bowel | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.265 |

| Sex and Vagina | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.380 |

| Dyspareunia | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.379 |

| General Sex Life | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 | Yes | ≤50 years | 0.374 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forshall, G.; Curtis, T.J.; Athey, R.; Turner-Moore, R.; Radley, S.C.; Jones, G.L. Symptom Burden, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs of Younger Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Content Analysis of ePAQ-Pelvic Floor Free-Text Responses. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155231

Forshall G, Curtis TJ, Athey R, Turner-Moore R, Radley SC, Jones GL. Symptom Burden, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs of Younger Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Content Analysis of ePAQ-Pelvic Floor Free-Text Responses. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155231

Chicago/Turabian StyleForshall, Georgina, Thomas J. Curtis, Ruth Athey, Rhys Turner-Moore, Stephen C. Radley, and Georgina L. Jones. 2025. "Symptom Burden, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs of Younger Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Content Analysis of ePAQ-Pelvic Floor Free-Text Responses" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155231

APA StyleForshall, G., Curtis, T. J., Athey, R., Turner-Moore, R., Radley, S. C., & Jones, G. L. (2025). Symptom Burden, Treatment Goals, and Information Needs of Younger Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Content Analysis of ePAQ-Pelvic Floor Free-Text Responses. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155231