Emergency Department Discharges Following Falls in Residential Aged Care Residents: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

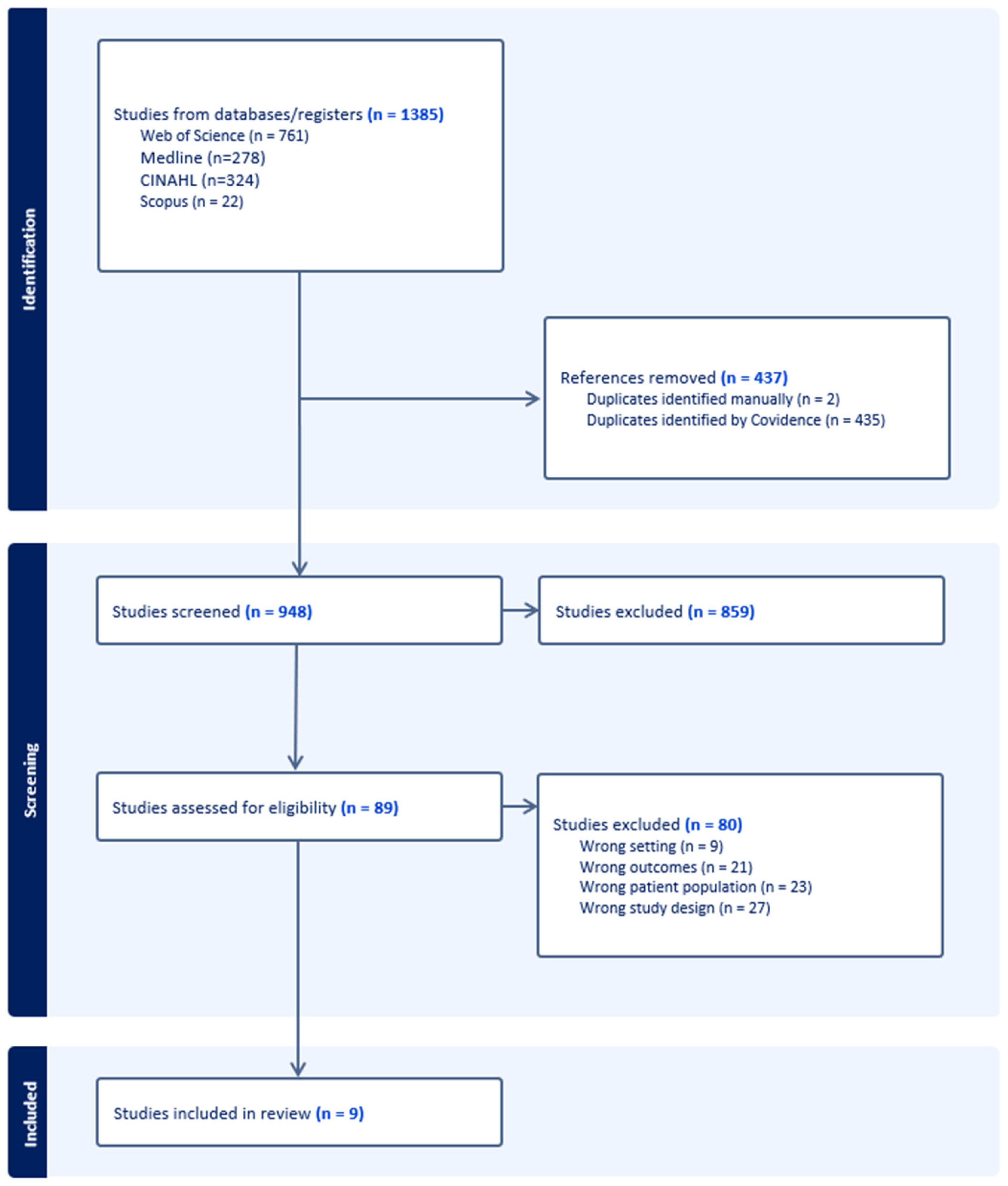

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Discharge Proportions from ED Post-Fall in RACF Patients

3.3. ACD and CTB Post-Fall from RACFs

4. Discussion

4.1. Reasons to Transfer to ED Post-Fall from RACFs

4.2. Respecting Patients’ Wishes: A Collaborative Approach for ED Transfers

4.3. High Study Heterogeneity

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Terms

- nursing home* OR Residential aged care* OR Assisted living* OR Long-term care facilit* OR Convalescent home* OR Retirement home* OR Care home* OR Memory care facilit*

- Fall* OR “Mechanical fall*” OR “Accidental fall*” OR “Fall from standing height” OR “Traumatic fall*” OR “Fall from chair”

- “Emergency care*” OR “Trauma care*” OR “Acute care*” OR “Emergency department*” OR “A and E*” OR “Accident and emergency*”

- Older patient* OR Geriatric* OR Elder* OR Aged OR Advanced age* OR Frail elderly* OR Older adult*

References

- Cameron, I.D.; Dyer, S.M.; Panagoda, C.E.; Murray, G.R.; Hill, K.D.; Cumming, R.G.; Kerse, N. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9, CD005465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Turrise, S.; MacLaughlin, E.J.; Chang, P.-S.; Clair, W.K.; Lewis, E.F.; Forman, D.E.; Goodlin, S.J.; on behalf of the American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Older Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; et al. Preventing and Managing Falls in Adults with Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 15, e000108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Vaish, A. Falls in Older Adults are Serious. Indian J. Orthop. 2020, 54, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, P.; Alan, J.; Porock, D. Emergency department transfers from residential aged care: What can we learn from secondary qualitative analysis of Australian Royal Commission data? BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugeja, L.; Woolford, M.H.; Willoughby, M.; Ranson, D.; Ibrahim, J.E. Frequency and nature of coroners’ recommendations from injury-related deaths among nursing home residents: A retrospective national cross-sectional study. Inj. Prev. 2018, 24, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stippler, M.; Smith, C.; McLean, A.R.; Carlson, A.; Morley, S.; Murray-Krezan, C.; Kraynik, J.; Kennedy, G. Utility of routine follow-up head CT scanning after mild traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of the literature. Emerg. Med. J. 2012, 29, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesen, B.; Merten, H.; Barendregt, R.; Bonjer, H.J.; Wagner, C.; Nanayakkara, P.W.B. Root causes and preventability of emergency department presentations of older patients: A prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, R.Y.; Niedzwiecki, M. Avoidable emergency department visits: A starting point. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Ranmuthugala, G.; Michel, K.; Corke, C. Factors Associated with Emergency Department Discharge After Falls in Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Rural Australian Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, J.C.; Lord, S.R.; Antonova, E.J.; Martin, M.; Lensberg, B.; Taylor, M.; Hallen, J.; Kelly, A. Older people presenting to the emergency department after a fall: A population with substantial recurrent healthcare use. Emerg. Med. J. 2012, 29, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.; Selleck, L.; Gibbons, M.; Klim, S.; Ritchie, P.; Patel, R.; Pham, C.; Kelly, A.M. Does the evidence justify routine transfer of residents of aged care facilities for CT scan after minor head trauma? Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullick, D.; Islam, M.R. Exploring avoidable presentations from residential aged care facilities to the emergency department of a large regional Australian hospital. Aust. J. Rural Health 2023, 31, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthuman, A.; Kim, T.H.; Gu, D. Understanding the Clinical Profile and Hospitalisation Patterns of Residents from Aged Care Facilities: A Regional Victorian Hospital Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e42694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulchinsky, I.; Buckley, R.; Meek, R.; Lim, J.J.Y. Potentially avoidable emergency department transfers from residential aged care facilities for possible post-fall intracranial injury. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2023, 35, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso-Argilés, F.J.; Serrano, M.C.; Oliveres, X.C.; Lorenzo, I.C.; Pérez, D.G.; Lafarga, T.P.; Tomás, X.I.; Puig-Campmany, M.; Martínez, A.V.; Renom-Guiteras, A. Emergency department admissions and economic costs burden related to ambulatory care sensitive conditions in older adults living in care homes. Rev. Clínica Española (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 223, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, D.H.; Oh, J. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of trauma in older patients transferred from long-term care hospitals to emergency departments: A nationwide retrospective study in South Korea. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 115, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.W.; Keating, T.; Brazil, E.; Power, D.; Duggan, J. Impact of season, weekends and bank holidays on emergency department transfers of nursing home residents. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 185, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsebom, M.; Hedstrom, M.; Wadensten, B.; Poder, U. The frequency of and reasons for acute hospital transfers of older nursing home residents. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 58, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulenbroeks, I.; Mercado, C.; Gates, P.; Nguyen, A.; Seaman, K.; Wabe, N.; Silva, S.M.; Zheng, W.Y.; Debono, D.; Westbrook, J. Effectiveness of fall prevention interventions in residential aged care and community settings: An umbrella review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venaglia, K.; Fox, A.; MacAndrew, M. Post-fall outcomes of aged care residents that did not transfer to hospital following referral to a specialised hospital outreach service: A retrospective cohort study. Collegian 2024, 31, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umegaki, H. Hospital-associated complications in frail older adults. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2024, 86, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Howard, M.A.; Han, J.H., III. Delirium and Delirium Prevention in the Emergency Department. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 39, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendts, G.; Quine, S.; Howard, K. Decision to transfer to an emergency department from residential aged care: A systematic review of qualitative research. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donzé, J.; Clair, C.; Hug, B.; Rodondi, N.; Waeber, G.; Cornuz, J.; Aujesky, D. Risk of falls and major bleeds in patients on oral anticoagulation therapy. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.; Elmasry, Y.; van Poelgeest, E.; Welsh, T.J. Anticoagulant use in older persons at risk for falls: Therapeutic dilemmas-a clinical review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 14, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzio, T.J.; Murphy, P.B.; Kregel, H.R.; Ellis, R.C.; Holder, T.; Wandling, M.W.; Wade, C.E.; Kao, L.S.; McNutt, M.K.; Harvin, J.A. Delayed Intracranial Hemorrhage after Blunt Head Trauma while on Direct Oral Anticoagulant: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2021, 232, 1007–1016.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.; Detering, K.M.; Low, T.; Nolte, L.; Fraser, S.; Sellars, M. Doctors’ perspectives on adhering to advance care directives when making medical decisions for patients: An Australian interview study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marincowitz, C.; Preston, L.; Cantrell, A.; Tonkins, M.; Sabir, L.; Mason, S. What influences decisions to transfer older care-home residents to the emergency department? A synthesis of qualitative reviews. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, C.; Unwin, M.; Peterson, G.M.; Stankovich, J.; Kinsman, L. Emergency department crowding: A systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year, Country | Total Number of Participants | Number of Falls | Number (%) of Falls Discharged | Participant Age Mean (SD) | ACD Status | CTB Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afonso-Argilés et al., 2023, Spain [16] | 1982 patients (2444 presentations) | 1384 | 768 (55%) | 85.9 (7.2) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Choi et al., 2023, Korea [17] | 14,469 | 7193 | 2576 (36%) | 80.8 (7.3) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Close et al., 2011, Australia [11] | 18,902 presentations | 589 | 324 (55%) | 80.8 (6.7) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Fan et al., 2015, Ireland [18] | 465 patients (802 presentations) | 126 | 63 (50%) | 82.7 (7.4) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Green et al., 2020, Australia [12] | 366 | 366 | 332 (91%) | 86 (IQR 81–91) | Not mentioned | 80.3% had CTB scans |

| Gullick et al., 2022, Australia [13] | 448 | 143 | 98 (69%) | 84 | ACD documented in 63% | Not mentioned |

| Kirsebom et al., 2013, Sweden [19] | 594 | 147 | 91 (61%) | 87 (7.2) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Tulchinsky et al., 2023, Australia [15] | 784 | 721 | 569 (79%) | 88 (IQR 83–93) | ACD documented in 50% | 68.6% had CTB scans |

| Uthuman et al., 2023, Australia [14] | 310 patients (467 presentations) | 155 | 111 (72%) | 84.5 (9.1) | ACD documented in 57% | Not mentioned |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, G.; Michel, K.; Corke, C.; Ranmuthugala, G. Emergency Department Discharges Following Falls in Residential Aged Care Residents: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145169

Guan G, Michel K, Corke C, Ranmuthugala G. Emergency Department Discharges Following Falls in Residential Aged Care Residents: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(14):5169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145169

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Gigi, Kadison Michel, Charlie Corke, and Geetha Ranmuthugala. 2025. "Emergency Department Discharges Following Falls in Residential Aged Care Residents: A Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 14: 5169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145169

APA StyleGuan, G., Michel, K., Corke, C., & Ranmuthugala, G. (2025). Emergency Department Discharges Following Falls in Residential Aged Care Residents: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(14), 5169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14145169