Be Kind to Yourself: Testing Self-Compassion, Fear of Recurrence, and Generalized Anxiety in Women with Cancer Within a Multiple-Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Role of Self-Compassion in Mitigating Negative Emotions in People with Cancer

1.2. Psychological Flexibility and Coping as Potential Mediators

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analysis

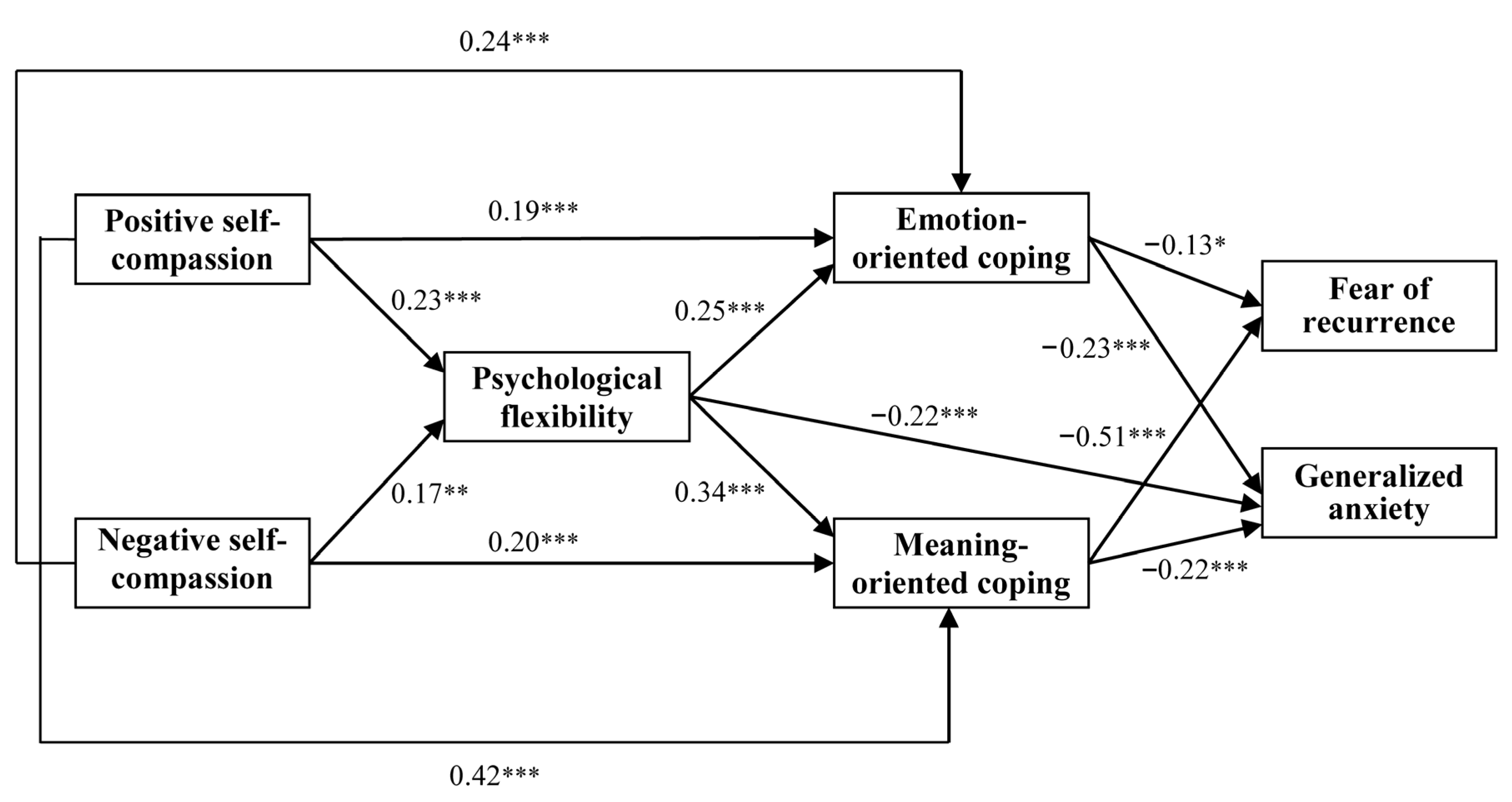

3.2. Multiple Mediation Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationships Among Self-Compassion, Fear of Recurrence, and Generalized Anxiety

4.2. The Serial and Parallel Mediation Effects

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, L.; Xie, J.; Wu, L.; Yao, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, A. Profiles of self-compassion and psychological outcomes in cancer patients. Psychooncology 2023, 32, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Artzi, T.J.; Baziliansky, S.; Cohen, M. The associations of emotion regulation, self-compassion, and perceived lifestyle discrepancy with breast cancer survivors’ healthy lifestyle maintenance. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K.D. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualisation of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Sanderman, R.; Smink, A.; Zhang, Y.; Van Sonderen, E.; Ranchor, A.; Schroevers, M.J. A reconsideration of the Self-Compassion Scale’s total score: Self-compassion versus self-criticism. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, R.E.; Heath, P.J.; Vogel, D.L.; Credé, M. Two is more valid than one: Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yao, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, Y.; Xie, J.; Schroevers, M.J. The predictive role of self-compassion in cancer patients’ symptoms of depression, anxiety, and fatigue: A longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 1918–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi Afrashteh, M.; Masoumi, S. Psychological well-being and death anxiety among breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of self-compassion. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, B.; Brebach, R.; Dzidowska, M.; Rhodes, P.; Sharpe, L.; Butow, P. Current approaches to managing fear of cancer recurrence: A descriptive survey of psychosocial and clinical health professionals. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengacher, C.A.; Shelton, M.M.; Reich, R.R.; Barta, M.K.; Johnson-Mallard, V.; Moscoso, M.S.; Kip, K.E. Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR(BC)) in breast cancer: Evaluating fear of recurrence (FOR) as a mediator of psychological and physical symptoms in a randomized control trial (RCT). J. Behav. Med. 2012, 37, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hernandez, E.; Romero, R.; Campos, D.; Burychka, D.; Diego-Pedro, R.; Baños, R.; Cebolla, A. Cognitively-Based Compassion Training (CBCT®) in breast cancer survivors: A randomized clinical trial study. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, J.; Julian, J.; Millar, J.; Prince, H.M.; Kenealy, M.; Herbert, K.; Burney, S.A. feasibility and acceptability study of an adaptation of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program for adult cancer patients. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.L.; Hughes, M.; Campbell, S.; Cherry, M.G. Could Worry and Rumination Mediate Relationships Between Self-Compassion and Psychological Distress in Breast Cancer Survivors? Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Yang, X.; Sun, S.; Yu, Y.; Xie, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Yao, J. Fear-Focused Self-Compassion Therapy for young breast cancer patients’ fear of cancer recurrence: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 941459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.C.; Hsiao, F.H.; Hsieh, C.C. The effectiveness of compassion-based interventions among cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat. Support. Care 2023, 21, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, C.; Paye, A.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A. Self-compassion-based interventions in oncology: A review of current practices. OBM Integr. Compliment. Med. 2024, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Contreras, J.P.; Sebri, V.; Sarrión-Castelló, P.; Martínez-Sanchís, S.; Martí, A.J.C.I. Efficacy of Compassion-Based Interventions in Breast Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Span. J. Psychol. 2024, 27, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wei, L.; Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Y.; Sun, S.; Xie, J. Self-compassion and fear of cancer recurrence in Chinese breast cancer patients: The mediating role of maladaptive cognitive styles. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 2185–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Xie, H.; Hu, Y.; Yao, J.; Fleer, J. Self-compassion and symptoms of depression and anxiety in Chinese cancer patients: The mediating role of illness perceptions. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2386–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özönder Ünal, I.; Ünal, C.; Duymaz, T.; Ordu, C. The relationship between psychological flexibility, self-compassion, and posttraumatic growth in cancer patients in the COVID-19 pandemic. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D.; Telka, E.; Falewicz, A.; Szcześniak, M. Total pain and fear of recurrence in post-treatment cancer patients: Serial mediation of psychological flexibility and mentalization and gender moderation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xie, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tian, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiao, W. Association among cognitive emotion regulation strategies, psychological flexibility and subjective well-being in patients with breast cancer: A cross-sectional latent profile and mediation analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajeri, M.; Alfooneh, A.; Imani, M. Studying the mediating role of psychological flexibility and self-compassion in the relationship between traumatic memories of shame and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms. Int. J. Body Mind Cult. 2023, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Mindfulness, self-compassion and psychological inflexibility mediate the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention in a sample of oncology nurses. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemeke, A.; Dudek, J.; Sobczyk-Kruszelnicka, M. The role of psychological flexibility in the meaning-reconstruction process in cancer: The intensive longitudinal study protocol. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Akcan, G.; Bakkal, B.H.; Elmas, Ö. The mediation role of coping with stress in the relationship between psychological flexibility and posttraumatic growth in cancer patients. OMEGA J. Death Dying 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Qiang, W.; Yin, X.; Lu, Q. The mediating effect of coping styles between self-compassion and body image disturbance in young breast cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.Y.; Yeung, N.C.Y. Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth: Cognitive processes as mediators. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindle, R.; Hemi, A.; Moustafa, A.A. Social support, psychological flexibility and coping mediate the association between COVID-19 related stress exposure and psychological distress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, S.; Gumley, A.; Cleare, C.J.; O’Connor, R.C. An investigation of the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggaley, J.A.; Wolverson, E.; Clarke, C. Measuring self-compassion in people living with dementia: Investigating the validity of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short form (SCS-SF). Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzios, M.; Koneva, A.; Egan, H. When ‘negativity’ becomes obstructive: A novel exploration of the two-factor model of the Self-Compassion Scale and a comparison of self-compassion and self-criticism interventions. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2020, 8, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Zettle, R.D. preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszczyńska, E.; Knoll, N. Meaning-focused coping, pain, and affect: A diary study of hospitalized women with rheumatoid arthritis. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 2873–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, K.F.; Aaronson, N.K.; Vasen, H.F.; Gerritsma, M.A.; Gundy, C.M.; Janssen, E.P.; Bleiker, E.M. Psychological distress and use of psychosocial support in familial adenomatous polyposis. Psychooncology 2010, 19, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Cho, K.B.; Park, K.S.; Jang, B.K.; Ryu, S.W. Comparison of quality of life and worry of cancer recurrence between endoscopic and surgical treatment for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 82, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Murguía, M.A.; Mazatán-Orozco, R.; Jiménez-Pacheco, S.E.; Padrós-Blázquez, F. A latent classes analysis to detect cognitive and emotional profiles in cancer patients. J. Health Psychol. 2025, 30, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon, C.; Gustems, M.; Galán-Moral, R.; Muñoz-Sánchez, M.M.; Ostios-García, L.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P. Fear of recurrence in advanced cancer patients: Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological correlates. Cancers 2024, 16, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Cariola, L.; Gillanders, D. Exploring the role of psychological flexibility in relationship functioning among couples coping with prostate cancer: A cross-sectional study. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, Y.; Fukawa, A. Factors related to the resilience and mental health of adult cancer patients: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3471–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D.; Telka, E.; Moroń, M. Personal resources and total pain: Exploring the multiple mediation of fear of recurrence, meaning-making, and coping in posttreatment cancer patients. Ann. Behav. Med. 2024, 58, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, D.; Xu, C.; Yan, X.; Chen, M.; et al. Effects of online mindful self-compassion intervention on negative body image in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trail. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 72, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedo, F.J.; Benedict, C.; Zhou, E.S.; Rasheed, M.; Traeger, L.; Park, J.; Nelson, C.; Solorzano, R.; Antoni, M.H. Association of stress management skills and perceived stress with physical and emotional well-being among advanced prostate cancer survivors following androgen deprivation treatment. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2013, 20, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive self-compassion | 3.75 | 0.75 | - | |||||||

| 2. Negative self-compassion | 3.55 | 0.72 | 0.42 *** | - | ||||||

| 3. Self-compassion (total) | 3.65 | 0.87 | 0.75 *** | 0.76 *** | - | |||||

| 4. Psychological flexibility | 4.87 | 1.00 | 0.30 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.34 *** | - | ||||

| 5. Problem-focused coping | 3.51 | 0.64 | 0.49 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.45 *** | - | |||

| 6. Emotion-focused coping | 3.29 | 0.65 | 0.37 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.43 *** | - | ||

| 7. Meaning-focused coping | 3.36 | 0.76 | 0.59 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.48 *** | - | |

| 8. Fear of recurrence | 2.10 | 0.65 | −0.37 *** | −0.32 *** | −0.41 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.58 *** | - |

| 9. Generalized anxiety | 2.25 | 0.86 | −0.22 *** | −0.13 * | −0.21 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.41 *** | −0.44 *** | 0.59 *** |

| Model Pathways | Estimate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Model with serial and parallel mediation effects Positive self-compassion → Psychological flexibility (Mediator 1) → Emotion-oriented coping/Meaning-oriented coping (Mediators 2) → Fear of recurrence | –0.28 a | –0.34 | –0.23 |

| Positive self-compassion → Psychological flexibility (Mediator 1) → Emotion-oriented coping/Meaning-oriented coping (Mediators 2) → Generalized anxiety | –0.21 a | –0.28 | –0.15 |

| Negative self-compassion → Psychological flexibility (Mediator 1) → Emotion-oriented coping/Meaning-oriented coping (Mediators 2) → Fear of recurrence | –0.17 a | –0.23 | –0.11 |

| Negative self-compassion → Psychological flexibility (Mediator 1) → Emotion-oriented coping/Meaning-oriented coping (Mediators 2) → Generalized anxiety | –0.16 a | –0.23 | –0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krok, D.; Telka, E.; Skalski-Bednarz, S.B. Be Kind to Yourself: Testing Self-Compassion, Fear of Recurrence, and Generalized Anxiety in Women with Cancer Within a Multiple-Mediation Model. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134696

Krok D, Telka E, Skalski-Bednarz SB. Be Kind to Yourself: Testing Self-Compassion, Fear of Recurrence, and Generalized Anxiety in Women with Cancer Within a Multiple-Mediation Model. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134696

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrok, Dariusz, Ewa Telka, and Sebastian Binyamin Skalski-Bednarz. 2025. "Be Kind to Yourself: Testing Self-Compassion, Fear of Recurrence, and Generalized Anxiety in Women with Cancer Within a Multiple-Mediation Model" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134696

APA StyleKrok, D., Telka, E., & Skalski-Bednarz, S. B. (2025). Be Kind to Yourself: Testing Self-Compassion, Fear of Recurrence, and Generalized Anxiety in Women with Cancer Within a Multiple-Mediation Model. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134696