International Consensus Guidelines on the Safe and Evidence-Based Practice of Mesotherapy: A Multidisciplinary Statement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. What Is New in This Recommendation

3. Methods

3.1. Question 1: How Should Mesotherapy Be Defined?

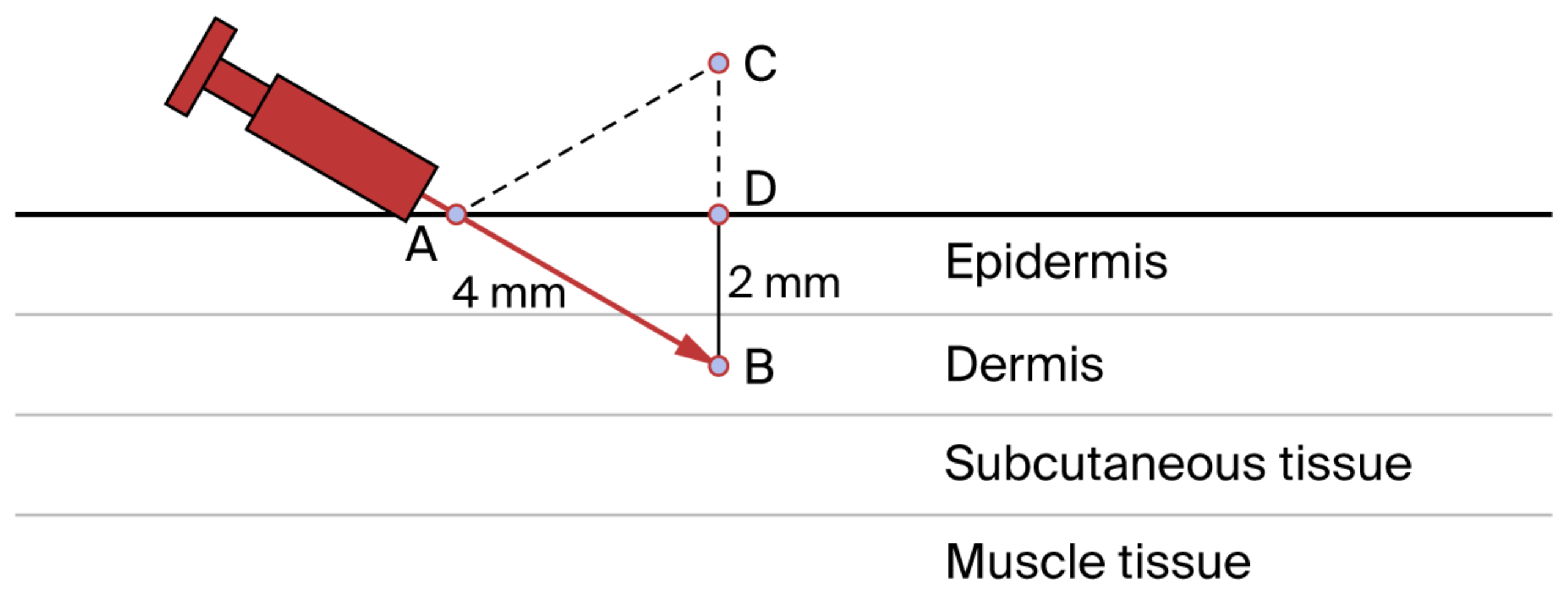

3.2. Question 2: How Is Mesotherapy Performed?

3.3. Question 3: What Is the Mechanism of Action of Mesotherapy?

3.4. Question 4: What Is the Advantage of the Drug-Sparing Effect of the Intradermal Route in Immunoprophylaxis?

3.5. Question 5: Which Substances Are Injected?

3.6. Question 6: Can Mesotherapy Be Included in the Management of Patients with Localized Musculoskeletal Pain?

3.7. Question 7: Can Mesotherapy Be Integrated into the Individual Rehabilitation Plan (IRP)?

3.8. Question 8: Can Sports Injuries Benefit from Mesotherapy?

3.9. Question 9: Can Mesotherapy Be Included in the Care Pathway for the Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Venous Disease (CVD) and the Prevention of Its Complications (PEFS)?

3.10. Question 10. Can Mesotherapy Be Considered in Dermatology?

3.11. Question 11: Can Mesotherapy Be Proposed for Managing Skin Aging?

3.12. Question 12: How Can Adverse Events Reported in the Literature Be Prevented?

- Like any other technique, mesotherapy may cause three types of adverse events:

- Events caused by the microtrauma produced by the needle (e.g., mild pain at the injection site and bruising) [115];

3.13. Question 13: Can Mesotherapy Technique Be Applied to the Oral Mucosa?

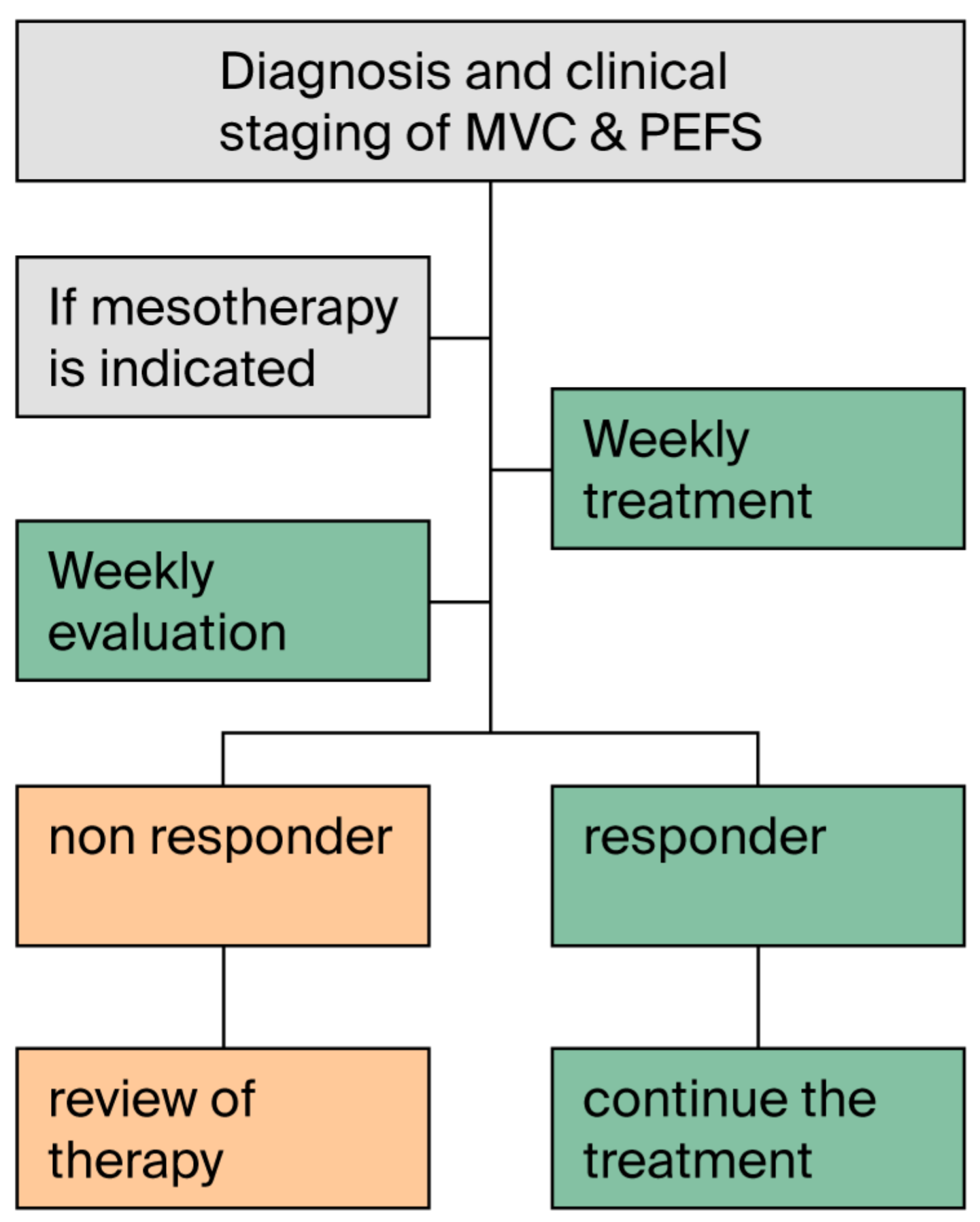

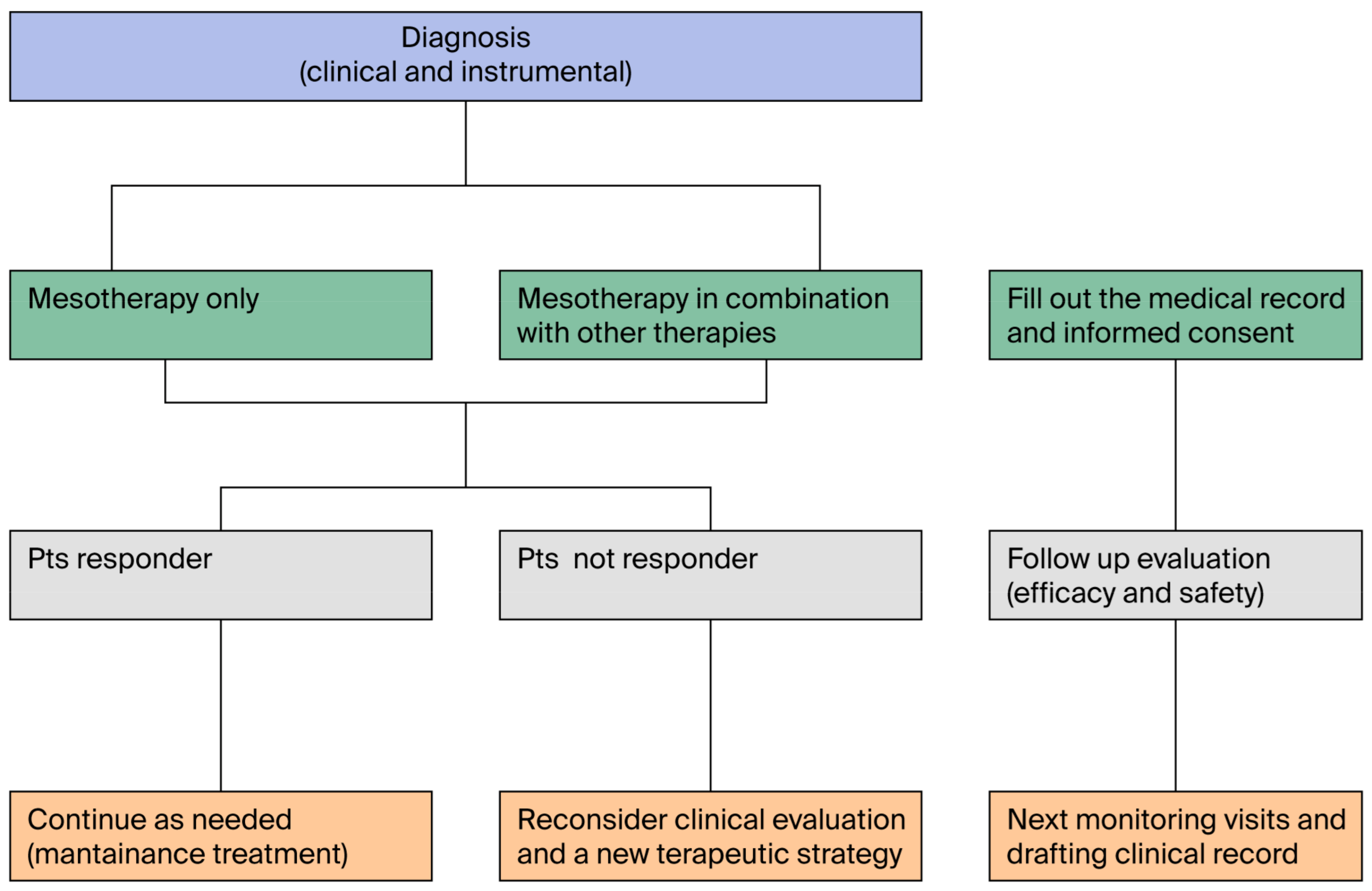

3.14. Questions 14 and 15: Can Mesotherapy Be Part of a Multimodal Treatment Strategy? What Treatment Algorithm Is Recommended for the Application of Mesotherapy?

3.15. Question 16: When Can Mesotherapy Be Applied in Clinical Practice?

3.16. Question 17: Are There Clinical Conditions That Contraindicate Mesotherapy?

3.17. Question 18: Is a Specific Informed Consent Required for Mesotherapy?

3.18. Question 19: Is It Necessary to Report the Effects of Mesotherapy in the Patient’s Medical Chart?

3.19. Question 20. Can Mesotherapy Be Performed on Minors?

3.20. Question 21: Who Can Practice Mesotherapy

3.21. Question 22: What Is the Role of Research?

3.22. Question 23: What Do Patients Recommend?

4. Potential Impact of the Guideline on Care Pathways

5. Emerging Recommendations

6. Limitations of This Document

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mammucari, M.; Gatti, A.; Maggiori, S.; Bartoletti, C.A.; Sabato, A.F. Mesotherapy, definition, rationale and clinical role: A consensus report from the Italian Society of Mesotherapy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 15, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mammucari, M.; Maggiori, E.; Antonaci, L.; Fanelli, R.; Giorgio, C.; George, F.; Mouhli, N.; Rahali, H.; Ksibi, I.; Maaoui, R.; et al. Intradermal therapy recommendations for standardization in localized pain management by the Italian Society of Mesotherapy. Minerva Med. 2019, 112, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammucari, M.; Russo, D.; Maggiori, E.; Paolucci, T.; Di Marzo, R.; Brauneis, S.; Bifarini, B.; Ronconi, G.; Ferrara, P.E.; Gori, F.; et al. Expert panel. Evidence based recommendations on mesotherapy: An update from the Italian society of Mesotherapy. Clin. Ter. 2021, 171, e37–e45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Law 8 March 2017, n. 24 “Provisions on the Safety of Care and of the Person Being Assisted, as well as on the Professional Liability of Those Practicing Health Professions” Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 64, 17 March 2017. Available online: https://www.parlamento.it/parlam/leggi/10038l.htm (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Mercuri, M.; Baigrie, B.S.; Gafni, A. Patient participation in the clinical encounter and clinical practice guidelines: The case of patients’ participation in a GRADEd world. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2021, 85, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kerkvliet, K.; Spithoff, K. AGREE Next Steps Consortium the AGREE Reporting Checklist: A Tool to Improve Reporting of Clinical Practice Guidelines. BMJ 2016, 352, i1152, Erratum in BMJ 2016, 354, i4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.E.; et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammucari, M.; Maggiori, E.; Russo, D.; Giorgio, C.; Ronconi, G.; Ferrara, P.E.; Canzona, F.; Antonaci, L.; Violo, B.; Vellucci, R.; et al. Mesotherapy: From Historical Notes to Scientific Evidence and Future Prospects. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 3542848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistor, M. Qu’est-ce que la mésothérapie? Chir. Dent. Fr. 1976, 46, 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rotunda, A.M.; Kolodney, M.S. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: Historical clarification and review. Dermatol. Surg. 2006, 32, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, M.; Tomaselli, F.; Maggiori, S. Intradermal injection vs. oral treatment of tinnitus. Therapie 2001, 56, 403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori, E. Trattato di Intradermo Terapia Distrettuale Mesoterapia; EMSI: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, R.; Garg, V.K.; Mysore, V. Position paper on mesotherapy. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2011, 77, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreros, F.O.; Moraes, A.M.; Velho, P.E. Mesotherapy: A bibliographical review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2011, 86, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammucari, M.; Vellucci, R.; Mediati, R.D.; Migliore, A.; Cuomo, A.; Maggiori, E.; Natoli, S.; Lazzari, M.; Gafforio, P.; Palumbo, E.; et al. What is mesotherapy? Recommendations from an international consensus. Trends Med. 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst, D.; Cooke, M.; Sriram, D.; Gray, B. Subcutaneous hydration and medications infusions (effectiveness, safety, acceptability): A systematic review of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammucari, M.; Paolucci, T.; Russo, D.; Maggiori, E.; Di Marzo, R.; Migliore, A.; Massafra, U.; Ronconi, G.; Ferrara, P.E.; Gori, F.; et al. A Call to Action by the Italian Mesotherapy Society on Scientific Research. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 3041–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, S. L’Intradermo Terapia Distrettuale; EMSI: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Plachouri, K.M.; Georgiou, S. Mesotherapy: Safety profile and management of complications. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 1601–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binaglia, L.; Marconi, P.; Pitzurra, M. Absorption of Na ketoprofen administered intradermally. J. Mesother. 1981, 1, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Binaglia, L.; Marconi, P.; Pitzurra, M. The diffusion of intradermally administered procaine. J. Mesother. 1981, 1, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pitzurra, M.; Cavallo, R.; Farinelli, S.; Sposini, T.; Cipresso, T.; Scaringi, L. The intradermal inoculation of antibiotics: Some experimental data. J. Mesother. 1982, 1, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mammucari, A.; Gatti, A.; Maggiori, S.; Sabato, A.F. Role of mesotherapy in musculoskeletal pain: Opinions from the Italian society of mesotherapy. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 436959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, I.; Kocak, A.O.; Kocak, M.B.; Cakir, Z. Comparison of intradermal mesotherapy with systemic therapy in the treatment of low back pain: A prospective randomized study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1431–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauneis, S.; Araimo, F.; Rossi, M.; Russo, D.; Mammucari, M.; Maggiori, E.; di Marzo, R.; Vellucci, R.; Gori, F.; Bifarini, B.; et al. The role of mesotherapy in the management of spinal pain. A randomized controlled study. Clin. Ter. 2023, 174, 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Paolucci, T.; Bellomo, R.G.; Centra, M.A.; Giannandrea, N.; Pezzi, L.; Saggini, R. Mesotherapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain in rehabilitation: The state of the art. J. Pain. Res. 2019, 12, 2391–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocak, A.O. Intradermal mesotherapy versus systemic therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: A prospective randomized study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 2061–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronconi, G.; Ferriero, G.; Nigito, C.; Foti, C.; Maccauro, G.; Ferrara, P.E. Efficacy of intradermal administration of diclofenac for the treatment of nonspecific chronic low back pain: Results from a retrospective observational study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.E.; Nigito, C.; Maccauro, G.; Ferriero, G.; Foti, C.; Ronconi, G. Efficacy of diclofenac mesotherapy for the treatment of chronic neck pain in spondylartrosis. Minerva Med. 2019, 110, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Machelska, H.; Schäfer, M. Peripheral analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of opioids. Z. Rheumatol. 2001, 60, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.S. Peripherally-acting opioids. Pain Physician 2008, 11 (Suppl. S2), S121–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasar, S.G.; Green, P.G.; Levine, J.D. Comparison of intradermal and subcutaneous hyperalgesic effects of inflammatory mediators in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1993, 153, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, H.; Calvo-Enrique, L.; Lopez, J.M.; Song, J.; Zhang, M.D.; Usoskin, D.; El Manira, A.; Adameyko, I.; Hjerling-Leffler, J.; Ernfors, P. Specialized cutaneous Schwann cells initiate pain sensation. Science 2019, 365, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K.E.; Moehring, F.; Stucky, C.L. Keratinocytes contribute to normal cold and heat sensation. eLife 2020, 9, e58625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crema, P.; Mancia, M. Reflex action in mesotherapy. J. Mesother. 1981, 1, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gattie, E.; Cleland, J.A.; Pandya, J.; Snodgrass, S. Dry Needling Adds No Benefit to the Treatment of Neck Pain: A Sham-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial with 1-Year Follow-Up. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, A.; Giombini, A.; Di Cesare, M.; Ripani, M.; Vulpiani, M.C.; Saraceni, V.M. Comparison between the effects of trigger point mesotherapy versus acupuncture points mesotherapy in the treatment of chronic low back pain: A short term randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2011, 19, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscito, R.; Ferrara, P.E.; Ljoka, C.; Pascuzzo, R.; Maggi, L.; Ronconi, G.; Foti, C. Mesotherapy as a treatment of pain and disability in patients affected by neck pain in spondylartrosis. Ig. Sanità Pubbl. 2018, 74, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, P.E.; Ronconi, G.; Viscito, R.; Pascuzzo, R.; Rosulescu, E.; Ljoka, C.; Maggi, L.; Ferriero, G.; Foti, C. Efficacy of mesotherapy using drugs versus normal saline solution in chronic spinal pain: A retrospective study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2017, 40, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ader, L.; Hanssen, B.; Wallin, G. Parturition pain treated by intracutaneous injections of sterile water. Pain 1990, 41, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.Z.; Geng, Z.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Feng, J.Y.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, X.B. Effects of intracutaneous injections of sterile water in patients with acute low back pain: A randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, e5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyucu, R.G.; Demirci, N.; Yumru, A.E.; Salman, S.; Ayanoglu, Y.T.; Tosun, Y.; Tayfur, C. Effects of Intradermal Sterile Water Injections in Women with Low Back Pain in Labor: A Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial. Balk. Med J. 2018, 35, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, O. Experimental skin pain induced by injection of water-soluble substances in humans. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 1961, 179, 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.D.; Tiwari, A.K.; Kennedy, J.L. Mechanisms of the placebo effect in pain and psychiatric disorders. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016, 16, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, R.; Stuhlreyer, J.; Schwartz, M.; Schmitz, J.; Colloca, L. Clinical Use of Placebo Effects in Patients with Pain Disorders. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2018, 139, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Damien, J.; Colloca, L.; Bellei-Rodriguez, C.É.; Marchand, S. Pain Modulation: From Conditioned Pain Modulation to Placebo and Nocebo Effects in Experimental and Clinical Pain. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2018, 139, 255–296. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, R.T.; Frech, S.A.; Muenz, L.R.; Villar, C.P.; Glenn, G.M. Dose sparing with intradermal injection of influenza vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2295–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egunsola, O.; Clement, F.; Taplin, J.; Mastikhina, L.; Li, J.W.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Dowsett, L.E.; Noseworthy, T. Immunogenicity and Safety of Reduced-Dose Intradermal vs Intramuscular Influenza Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2035693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coudeville, L.; Andre, P.; Bailleux, F.; Weber, F.; Plotkin, S. A new approach to estimate vaccine efficacy based on immunogenicity data applied to influenza vaccines administered by the intradermal or intramuscular routes. Hum. Vaccin. 2010, 6, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticchi, L.; Alberti, M.; Alicino, C.; Crovari, P. The intradermal vaccination: Past experiences and current perspectives. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2010, 51, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Khanlou, H.; Sanchez, S.; Babaie, M.; Chien, C.; Hamwi, G.; Ricaurte, J.C.; Stein, T.; Bhatti, L.; Denouden, P.; Farthing, C. The safety and efficacy of dose-sparing intradermal administration of influenza vaccine in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayasu, H.; Sein, C.; Chang Blanc, D.; Gonzalez, A.R.; Zehrung, D.; Jarrahian, C.; Macklin, G.; Sutter, R.W. Intradermal Administration of Fractional Doses of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine: A Dose-Sparing Option for Polio Immunization. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S161–S167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2018—Recommendations. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5500–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, J.M. Intradermal injection of reduced-dose influenza vaccine was immunogenic in young adults. ACP J. Club. 2005, 142, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliore, A.; Gigliucci, G.; Di Marzo, R.; Russo, D.; Mammucari, M. Intradermal Vaccination: A Potential Tool in the Battle Against the COVID-19 Pandemic? Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrini, M.; Bergamaschi, R.; Azzoni, R. Controlled study of acetylsalicylic acid efficacy by mesotherapy in lumbo-sciatic pain. Minerva Ortop. E Traumatol. 2002, 53, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Monticone, M.; Barbarino, A.; Testi, C.; Arzano, S.; Moschi, A.; Negrini, S. Symptomatic efficacy of stabilizing treatment versus laser therapy for sub-acute low back pain with positive tests for sacroiliac dysfunction: A randomised clinical controlled trial with 1 year follow-up. Eura. Medicophys. 2004, 40, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, C.; Marangio, E.; Coruzzi, G. Mesotherapy Versus Systemic Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 317183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchio, A.; De Blasis, E.; Desiati, P.; Spacca, G.; Santilli, V.; De Paulis, F. Effectiveness of treatment of calcific tendinitis of the shoulder by disodium EDTA. Arthritis Care Res. 2009, 61, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, S.; Riello, R.; Cammardella, M.P.; Carossino, D.; Orlandini, G.; Casigliani, R.; Launo, C. TENS+ mesotherapy association in the therapy of cervico-brachialgia: Preliminary data. Minerva Anestesiol. 1991, 57, 1084–1085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faetani, L.; Ghizzoni, D.; Ammendolia, A.; Costantino, C. Safety and efficacy of mesotherapy in musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials with meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, jrm00182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farpour, H.R.; Estakhri, F.; Zakeri, M.; Parvin, R. Efficacy of Piroxicam Mesotherapy in Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 6940741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseveendorj, N.; Sindel, D.; Arman, S.; Sen, E.I. Efficacy of Mesotherapy for Pain, Function and Quality of Life in Patients with Mild and Moderate Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact. 2023, 23, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wiruchpongsanon, P. Relief of low back labor pain by using intracutaneous injections of sterile water: A randomized clinical trial. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2006, 89, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, D.; Zhong, J.; Qiu, B.; Wu, X. Therapeutic effectiveness and safety of mesotherapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 4, 6513049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, T.; Piccinini, G.; Trifan, P.D.; Zangrando, F.; Saraceni, V.M. Efficacy of Trigger Points Mesotherapy for the Treatment of Chronic Neck Pain: A Short Term Retrospective Study. Int. J. Phys. Ther. Rehab. 2016, 2, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.N.; Geng, Z.S.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, X.B.; Cui, J.Z. Single intracutaneous injection of local anesthetics and steroids alleviates acute nonspecific neck pain: A CONSORT-perspective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Medicine 2018, 97, e11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggini, R.; Di Stefano, A.; Dodaj, I.; Scarcello, L.; Bellomo, R.G. Pes Anserine Bursitis in Symptomatic Osteoarthritis Patients: A Mesotherapy Treatment Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2015, 21, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaturro, D.; Vitagliani, F.; Signa, G.; Tomasello, S.; Tumminelli, L.G.; Picelli, A.; Smania, N.; Letizia Mauro, G. Neck Pain in Fibromyalgia: Treatment with Exercise and Mesotherapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.E.; Ronconi, G.; Viscito, R.; Maggi, L.; Bertolini, C.; Ljoka, C.; Ferriero, G.; Foti, C. Short-term and medium-term efficacy of mesotherapy in patients with lower back pain due to spondyloarthrosis. Ig. Sanita Pubbl. 2017, 73, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mårtensson, L.; Wallin, G. Labour pain treated with cutaneous injections of sterile water: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1999, 106, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Straube, S.; Moore, R.A.; Hancock, H.; Collins, S.L. Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection compared with blinded controls for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, CD009107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; Attanasi, C.; Bernetti, A.; Mangone, M.; Paoloni, M.; Del Monte, E.; Mammucari, M.; Maggiori, E.; Russo, D.; Marzo, R.D.; et al. Web Axillary Pain Syndrome-Literature Evidence and Novel Rehabilitative Suggestions: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2021, 18, 10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhli, N.; Belghith, S.; Karoui, S.; Slouma, M.; Dhahri, R.; Ajili, F.; Maaoui, R.; Rahali, H. Comparison of Mesotherapy and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) in the Management of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Tunis. Med. 2025, 103, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cereser, C.; Ganzit, G.P.; Gribaudo, C. Injuries affecting the locomotory system during the game of rugby. Reports of 133 cases treated with mesotherapy. G. Mesoterapia 1985, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudo, C.G.; Ganzit, G.P.; Astegiano, P. Mesotherapy in treating pubic myoenthesitis. G. di Mesoterapia 1982, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore, F.; Savino, V. Acute lumbo sciatic pain in athletes. G. Mesoterapia 1983, 3, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudo, C.G.; Ganzit, G.P.; Canata, G.L.; Gerbi, G. Patellar tendonitis: Treatment with ergotein in mesotherapy. G. Mesoterapia 1986, 6, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudo, C.G.; Ganzit, G.P.; Astegiano, P.; Canata, G.L. Mesotherapy in treatment of the ileo-tibial band friction syndrome. G. Mesoterapia 1986, 6, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudo, C.G.; Canata, G.L.; Ganzit, G.P.; Gerbi, G. Mesotherapy in the treatment of myoenthesitis of the leg in athletes. G. Mesoterapia 1987, 7, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- De Melo Sposito, M.M.; Rivera, D.; Riberto, M.; Metsavaht, L. Mesotherapy improves range of motion in patients with rotator cuff tendinitis. Acta Fisiatr. 2011, 18, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Mallah, R.; Elattar, E.A. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy versus musculoskeletal mesotherapy for Achilles tendinopathy in athlete. Egypt. Rheumatol. Rehabil. 2020, 47, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Glucocorticoids and Therapeutic Use Exemptions. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/glucocorticoids_and_therapeutic_use_exemptions_final_20oct21.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- De Maeseneer, M.G.; Kakkos, S.K.; Aherne, T.; Baekgaard, N.; Black, S.; Blomgren, L.; Giannoukas, A.; Gohel, M.; de Graaf, R.; Hamel-Desnos, C.; et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 184–267, Erratum in Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 64, 284––285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, F.; Passman, M.; Meisner, M.; Dalsing, M.; Masuda, E.; Welch, H.; Bush, R.L.; Blebea, J.; Carpentier, P.H.; De Maeseneer, M.; et al. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2020, 8, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, C.; Hladik, C.; Hamade, H.; Frank, K.; Kaminer, M.S.; Hexsel, D.; Gotkin, R.H.; Sadick, N.S.; Green, J.B.; Cotofana, S. Structural Gender Dimorphism and the Biomechanics of the Gluteal Subcutaneous Tissue: Implications for the Pathophysiology of Cellulite. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 143, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlen, J.F.; Curri, S.B.; Sarteel, A.M. La cellulite, affection microvasculo-conjonctive. Phlebology 1979, 32, 279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides, A.; Kakkos, S.; Eklof, B.; Perrin, M.; Nelzen, O.; Neglen, P.; Partsch, H.; Rybak, Z. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs—Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int. Angiol. 2014, 33, 87–208. [Google Scholar]

- Andreozzi, G.M. Effectiveness of mesoglycan in patients with previous deep venous thrombosis and chronic venous insufficiency. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2007, 55, 741–753. [Google Scholar]

- Arosio, E.; Ferrari, G.; Santoro, L.; Gianese, F.; Coccheri, S. A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of mesoglycan in the treatment of chronic venous ulcers. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2001, 22, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggiori, E.; Bartoletti, C.A.; Maggiori, S.; Tomaselli, F.; Dorato, D. Local intradermotherapy (ITD) with mesoglicano in PEFS and IVLC, retrospective study. Trends Med. 2010, 10, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori, E.; Bartoletti, E.; Mammucari, M. Intradermal therapy (mesotherapy) with lymdiaral in chronic venous insufficiency and associated fibrosclerotic edema damage: A pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canzona, F.; Mammucari, M.; Tuzi, A.; Maggiori, E.; Grosso, M.G.; Antonaci, L.; Santini, S.; Catizzone, A.R.; Troili, F.; Gallo, A.; et al. Intradermal Therapy (Mesotherapy) in Dermatology. J. Dermatol. Skin. Sci. 2020, 2, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mammucari, M.; Maggiori, E.; Antonaci, L.; Fanelli, R.; Giorgio, C.; Catizzone, A.R.; Troili, F.; Gallo, A.; Guglielmo, C.; Russo, D.; et al. Rational for the Intradermal Therapy (Mesotherapy) in Sport Medicine: From Hypothesis to Clinical Practise. Res. Investig. Sports Med. 2019, 5, RISM.000619.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Polla Ravi, S.; Wang, T.; Talukder, M.; Starace, M.; Piraccini, B.M. Systematic review of mesotherapy: A novel avenue for the treatment of hair loss. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2023, 34, 2245084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aledani, E.M.; Kaur, H.; Kasapoglu, M.; Nawaz, S.; Althwanay, A.; Nath, T.S.; AlEdani, E.M. Mesotherapy as a Promising Alternative to Minoxidil for Androgenetic Alopecia: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e59705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Cuadrado, F.J.; Pinto-Pulido, E.L.; Fernández-Parrado, M. Mesotherapy with dutasteride for androgenetic alopecia: A concise review of the literature. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2023, 33, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, M.; Amiri, R.; Iranmanesh, B.; Zartab, H.; Aflatoonian, M. Safety and efficacy of mesotherapy in the treatment of melasma: A review article. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashikar, Y.; Madke, B.; Singh, A.; Meghe, S.; Rusia, K. Mesotherapy for Melasma—An Updated Review. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2024, 16 (Suppl. S2), S1055–S1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Hyun, M.Y.; Park, K.Y.; Kim, B.J. A tip for performing intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections in acne patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, e127–e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.A.; Mehrose, M.Y.; Saleem, M.; Yousaf, M.A.; Mujahid, A.M.; Rehman, S.U.; Ahmad, S.; Tarar, M.N. Comparison of efficacy and safety of intralesional triamcinolone and combination of triamcinolone with 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars: Randomised control trial. Burns 2019, 45, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkat, M.T.; Abdel-Aziz, R.T.A.; Mohamed, M.S. Evaluation of intralesional injection of bleomycin in the treatment of plantar warts: Clinical and dermoscopic evaluation. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Kang, S.; Varani, J.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Wan, Y.; Datta, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Mechanisms of photoaging and chronological skin aging. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, G.; Saurat, J.H. Dermatoporosis: A chronic cutaneous insufficiency/fragility syndrome. Clinicopathological features, mechanisms, prevention and potential treatments. Dermatology 2007, 215, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; De Padova, M.P.; Tosti, A. Biorejuvenation: Theory and practice. Clin. Dermatol. 2008, 26, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanian, F.; Deutsch, J.J.; Bousquet, M.T.; Boisnic, S.; Andre, P.; Catoni, I.; Beilin, G.; Lemmel, C.; Taieb, M.; Gomel-Toledano, M.; et al. A hyaluronic acid-based micro-filler improves superficial wrinkles and skin quality: A randomized prospective controlled multicenter study. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2023, 34, 2216323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duteil, L.; Queille-Roussel, C.; Issa, H.; Sukmansaya, N.; Murray, J.; Fanian, F. The Effects of a Non-Crossed-Linked Hyaluronic Acid Gel on the Aging Signs of the Face Versus Normal Saline: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Split-Faced Study. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Płatkowska, A.; Korzekwa, S.; Łukasik, B.; Zerbinati, N. Combined Bipolar Radiofrequency and Non-Crosslinked Hyaluronic Acid Mesotherapy Protocol to Improve Skin Appearance and Epidermal Barrier Function: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.P.; Phelps, R.G.; Goldberg, D.J. Mesotherapy for facial skin rejuvenation: A clinical, histologic, and electron microscopic evaluation. Dermatol. Surg. 2006, 32, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, A.G.; Ivanic, M.G.; Botros, M.A.; Pope, R.W.; Halle, B.R.; Glassman, G.E.; Genova, R.; Al Kassis, S. Rejuvenating the periorbital area using platelet-rich plasma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyeh, B.S.; Abou Ghanem, O. An Update on Facial Skin Rejuvenation Effectiveness of Mesotherapy EBM V. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2021, 32, 2168–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSM Médecine Esthétique: L’usage de Concentrés Plaquettaires Autologues (CPA ou PRP) à Visée Esthétique est Interdit. Available online: https://ansm.sante.fr/actualites/medecine-esthetique-lusage-de-concentres-plaquettaires-autologues-cpa-ou-plasma-riche-en-plaquettes-prp-a-visee-esthetique-est-interdit (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ghatge, A.S.; Ghatge, S.B. The Effectiveness of Injectable Hyaluronic Acid in the Improvement of the Facial Skin Quality: A Systematic Review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. ASPS Policy Statement on Mesotherapy/Injection Lipolysis. Available online: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/Health-Policy/Resources/2019-mesotherapy-injection-lipolysis.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Brandão, C.; Fernandes, N.; Mesquita, N.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Silva, R.; Viana, H.L.; Dias, L.M. Abdominal haematoma—A mesotherapy complication. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2005, 85, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilovic, D.L.; Bloise, W.; Knobel, M.; Marui, S. Factitious thyrotoxicosis induced by mesotherapy: A case report. Thyroid 2008, 18, 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Moon, W.; Park, S.J.; Park, M.I.; Kim, K.-J.; Lee, J.N.; Kang, S.J.; La Jang, L.; Chang, H.K. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Rao, B. Mesotherapy-induced panniculitis treated with dapsone: Case report and review of reported adverse effects of mesotherapy. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2006, 10, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, J.; Piémont, Y.; Truchetet, F.; Cattan, E. Mesotherapy and cutaneous mycobacteriosis caused by Mycobacterium fortuitum: Alternative medicine at risk. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 1987, 114, 845–849. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey, R.C.; de Waard, J.H.; Yakrus, M.A.; Rivera, I.; Chopite, M.; Toney, S.R.; Morlock, G.P.; Butler, W.R. Mycobacterium cosmeticum sp. nov., a novel rapidly growing species isolated from a cosmetic infection and from a nail salon. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54 Pt 6, 2385–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Navarro, X.; Barnadas, M.A.; Dalmau, J.; Coll, P.; Gurguí, M.; Alomar, A. Mycobacterium abscessus infection secondary to mesotherapy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 33, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmat, S.A.; El-Sayed, N.M.; Fahmy, R.A. Vitamin C mesotherapy versus diode laser for the esthetic management of physiologic gingival hyperpigmentation: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral. Health 2023, 23, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, A.; Kamra, P.; Anand, D.; Nayyar, V.; Mishra, D.; Pandey, S. Oral mesotherapy technique for the treatment of physiologic gingival melanin hyperpigmentation using locally injectable vitamin C: A clinical and histologic cases series. Quintessence Int. 2022, 53, 580–588. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mofty, M.; Elkot, S.; Ghoneim, A.; Yossri, D.; Ezzatt, O.M. Vitamin C mesotherapy versus topical application for gingival hyperpigmentation: A clinical and histopathological study. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2021, 25, 6881–6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yussif, N.M.; Abdel Rahman, A.R.; ElBarbary, A. Minimally invasive non-surgical locally injected vitamin C versus the conventional surgical depigmentation in treatment of gingival hyperpigmentation of the anterior esthetic zone: A prospective comparative study. Clin. Nutr. Exp. 2019, 24, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinas, G.; Solinas, A.L.; Perra, P.; Solinas, F.L. Treatment of mechanical tendinopathies by mesotherapy with orgotein in combination with laser therapy. Riabilitazione 1987, 20, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh, B.; Khalili, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Amiri, R.; Aflatoonian, M. The efficacy of energy-based devices combination therapy for melasma. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Han, W.; Li, S.; Nie, Y.; Chen, P.; Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, L. Effects of mesotherapy introduction of compound glycyrrhizin injection on the treatment of moderate to severe acne. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 1973–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammucari, M.; Maggiori, E.; Lazzari, M.; Natoli, S. Should the General Practitioner Consider Mesotherapy (Intradermal Therapy) to Manage Localized Pain? Pain. Ther. 2016, 5, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammucari, M. Mesotherapy (intradermal therapy) to reduce the systemic risk of NSAIDs in real practice. BMJ 2017, 357, j1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammucari, M.; Lazzari, M.; Maggiori, E.; Gafforio, P.; Tufaro, G.; Baffini, S.; Maggiori, S.; Palombo, E.; de Meo, B.; Sabato, A.F.; et al. Role of the informed consent, from mesotherapy to opioid therapy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meadows, W.A.; Hollowell, B.D. “Off-label” drug use: An FDA regulatory term, not a negative implication of its medical use. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2008, 20, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttila, J.; Siira, H.; Kyngäs, H.; Lahtinen, M.; Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kaakinen, P.; Oikarinen, A.; Yamakawa, M.; Fukui, S.; et al. Healthcare professionals’ competence in digitalisation: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventegodt, S.; Morad, M.; Merrick, J. Clinical holistic medicine: The “new medicine”, the multiparadigmatic physician, and the medical record. Sci. World J. 2004, 4, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, R.; Chugh, P.K.; Tripathi, C.D.; Lhamo, Y.; Gautam, S. Pediatric Off-Label and Unlicensed Drug Use and Its Implications. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 12, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottone, E.; Giordani, G. Experimental observations on the effects of intracutaneous prednisolone succinate. Minerva Pediatr. 1957, 9, 998–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Bottone, E.; Giordani, G. Experimental observations on the role of the hypothalamus in the hypophyseal and adrenal response to intracutaneous ACTH. Minerva Pediatr. 1956, 8, 728–731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, O.; Venezia, A. Therapeutic effects of prednisolone hemisuccinate in intracutaneous administration in asthmatic syndromes. Riv. Clin. Pediatr. 1959, 64, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, A.; Aizawa, Y.; Sato, I.; Hirano, H.; Sakai, T.; Mori, M. Skin thickness in young infants and adolescents: Applications for intradermal vaccination. Vaccine 2015, 33, 3384–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarah, S.; Sharma, M.; Wen, J. Recent advances in microneedle-based drug delivery: Special emphasis on its use in paediatric population. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 136, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, K.; Das, D.B. Microneedles for drug delivery: Trends and progress. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 2338–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, L.L.; Guo, Q. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture in children: An overview of systematic reviews. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 78, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, A.; Lund, I.; Boström, A.; Hyytiäinen, H.; Asplund, K. A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”. Animals 2021, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.; Jorge, P.; Santos, A. Comparison of Two Mesotherapy Protocols in the Management of Back Pain in Police Working Dogs: A Retrospective Study. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2021, 43, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, M.; Rumi, F.; Palmeri, M.; Mattozzi, I.; Manzoli, L.; Mammucari, M.; Gigliotti, S.; Bernabei, R.; Cicchetti, A. Cost-of-illness dell’osteoartrite in Italia: Burden economico dell’inappropriatezza prescrittiva. Glob. Reg. Health Technol. Assess. 2020, 7, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

| N | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | How should mesotherapy be defined? |

| 2 | How is mesotherapy performed? |

| 3 | What is the mechanism of action of mesotherapy? |

| 4 | What is the advantage of the drug-sparing effect of the intradermal route in immunoprophylaxis? |

| 5 | Which substances are injected? |

| 6 | Can mesotherapy be included in the management of patients with localized musculoskeletal pain? |

| 7 | Can mesotherapy be integrated into the Individual Rehabilitation Plan (IRP)? |

| 8 | Can sports trauma benefit from mesotherapy? |

| 9 | Can mesotherapy be included in the care pathway for the signs and symptoms of chronic venous disease (CVD) and the prevention of its complications (PEFS)? |

| 10 | Can mesotherapy be considered in dermatology? |

| 11 | Can the mesotherapy technique be proposed for the management of skin aging? |

| 12 | How can the adverse events reported in the literature be prevented? |

| 13 | Can the mesotherapy technique be applied to the oral mucosa? |

| 14 | Can mesotherapy be part of a multimodal treatment strategy? |

| 15 | What treatment algorithm is recommended for the application of mesotherapy? |

| 16 | When can mesotherapy be applied in clinical practice? |

| 17 | Are there any clinical conditions that contraindicate mesotherapy? |

| 18 | Is a specific informed consent required for mesotherapy? |

| 19 | Is it necessary to report the effects of mesotherapy in the patient’s medical chart? |

| 20 | Can mesotherapy be performed on minors? |

| 21 | Who can practice mesotherapy? |

| 22 | What is the role of research? |

| 23 | What do patients recommend? |

| Level of Evidence | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Ia | Evidence from meta-analysis of randomized trials |

| Ib | Evidence obtained from at least one RCT |

| IIa | Evidence obtained from at least one well-designed controlled trial without randomization |

| IIb | Evidence obtained from at least one other well-designed experimental study |

| III | Evidence obtained from well-designed non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative, correlational and case studies |

| IV | Evidence obtained from expert reports or authoritative opinions and/or clinical experiences |

| No. | Definition of Mesotherapy | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 1 | The term “mesotherapy” describes the technique with which microinjections are performed into the thickness of the skin for preventive, curative or rehabilitative purposes | Q1 | IV | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 96.6% | 1.7% | 1.7% |

| 2 | The term “local intradermal therapy” describes the technique with which a series of microinjections are performed in the superficial dermis of a specific skin area | Q1 | IV | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 97.5% | 1.7% | 0.8% |

| No. | Administration Technique | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 3 | Mesotherapy is performed with a 4mm (27 Gauge) or 13mm (30 G - 32 G) needle. Depending on the length of the needle and the thickness of the skin to be treated, the angle of inclination and the insertion depth of the needle itself will vary. The 4 mm needle inclined at 30° to the skin surface allows inoculation at approximately 2 mm depth. By increasing or reducing the inclination angle, different inoculation depths are obtained | Q2 | IV | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 94.1% | 3.4% | 2.5% |

| 4 | To carry out local intradermal therapy, the formation of micro drug deposits in the dermis (wheals) is recommended, to obtain which 0.1-0.2 ml of liquid must be inoculated for each single microinjection | Q2, Q3 | IV | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 94.1% | 3.4% | 2.5% |

| 5 | The distance between one microinjection and another varies from 1 to 2 cm | Q2 | IV | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 86.6% | 9.2% | 4.2% |

| 6 | Mesotherapy must be performed strictly observing the rules of asepsis | Q2 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 99.2% | 0.8% | 0.0% |

| 7 | If the use of two active ingredients is necessary, the administration of the individual products in different syringes and in different inoculation sites is recommended | Q2 | IV | 4.4 ± 1 | 83.2% | 10.1% | 6.7% |

| 8 | Multi-injectors are not recommended | Q2 | IV | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 83.2% | 10.90% | 5.9% |

| No. | Mechanism of Action | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 9 | The effect of mesotherapy depends on the predominantly local action of the injected drug to which systemic absorption, reactions induced by the needle, tissue distension caused by the liquid, cell-mediated and neuro- immune reactions can contribute. The set of these mechanisms is defined as “mesodermal modulation” | Q3 | IV | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 95.8% | 3.4% | 0.8% |

| 10 | Intradermal administration produces a series of wheals that constitute a “reserve” from which the drug is slowly absorbed with the aim of prolonging its effect | Q2, Q3 | IIb | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 97.5% | 1.7% | 0.8% |

| 11 | Mesotherapy allows a drug-sparing effect and an efficacy comparable to that of systemic therapy | Q3, Q4 | IIa | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 88.2% | 10.9% | 0.8% |

| No. | Drug-Sparing Effects on Immunoprophylaxis | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 12 | The intradermal route induces an antibody response equal to or greater than the intramuscular route, but with a lower dose of antigen | Q4 | Ib | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 90.8% | 9.2% | 0.0% |

| No. | Pharmacology | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 13 | To apply mesotherapy, the use of active ingredients indicated in the pathology or symptom to be treated is recommended | Q5 | IV | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 95.8% | 3.4% | 0.8% |

| 14 | In mesotherapy it is recommended to use injectable products and to consider those not indicated for the mesotherapy route as off-label | Q5, Q12 | IV | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 95.0% | 4.2% | 0.8% |

| 15 | The use of mixtures is permitted only if the products have authorization for use in combination or if they have efficacy and tolerability studies | Q5, Q12 | III | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 93.3% | 5.0% | 1.7% |

| Reference | Disease | Number of Patients | Comparison | Follow-Up | N of Sessions | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [60] | Cervico brachialgia | 20 | TENS | 20 days | 6 | Improvement and reduced need for therapy |

| [56] | Acute lumbosciatica | 44 | Placebo | 1 day | 1 | Good efficacy and tolerability |

| [57] | Low back pain | 22 | Laser | 1 year | 8 | Better results with mesotherapy |

| [58] | Low back pain | 84 | Systemic therapy | 6 months | 5 | Same effect as systemic therapy |

| [37] | Low back pain | 62 | Trigger points | 12 weeks | 4 | Better results of mesotherapy on trigger points |

| [59] | Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder | 80 | Placebo | 1 year | 3 | Reduction of calcifications |

| [64] | Acute low back pain | 68 | Placebo | 1 day | 1 | Improved pain, mobility, and quality of life |

| [65] | Osteoarthritis | 50 | Oral therapy | 6 months | 3 | Improved pain and functionality |

| [42] | Low back pain | 168 | Placebo | 1 day | 1 | Improved pain and quality of life |

| [66] | Chronic neck pain | 42 | Placebo | 3 months | 3 | Improved pain and quality of life |

| [67] | Acute neck pain | 36 | Oral therapy | 3 days | 1 | Improved pain and quality of life |

| [68] | Osteoarthritis | 117 | Oral therapy | 3 months | 9 | Improved pain and mobility |

| [39] | Chronic spinal pain | 217 | Placebo | 3 months | 5 | Improved pain and mobility |

| [69] | Fibromyalgia-related neck pain | 78 | Placebo | 3 months | 7 | Improved pain and functionality |

| [25] | Osteoarticular pain | 141 | 1 drug vs. 2 drugs | 3 months | 9 | Improved pain and reduced drug consumption |

| [24] | Low back pain in emergency dept | 120 | Intravenous therapy | 1 day | 1 | Mesotherapy superiority and reduced drug need |

| [27] | Acute musculoskeletal injuries in emergency dept | 96 | Intravenous therapy | 1 day | 1 | Mesotherapy superiority and reduced drug need |

| No. | Localized Pain | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 16 | Mesotherapy represents an option in the management of localized musculoskeletal pain | Q6 | Ia | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 98.3% | 1.7% | 0.0% |

| 17 | Mesotherapy is recommended in the management of localized pain when the drug-sparing effect and the potential lower systemic pharmacological impact represent an advantage | Q6, Q7, Q8 | Ia | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 96.6% | 3.4% | 0.0% |

| 18 | It is recommended to determine the frequency, number of sessions and duration of treatment based on the clinical response. The available studies report a frequency of sessions usually weekly with a number of sessions from 1 to 9 | Q6, Q7, Q8 | Ib | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 97.5% | 2.5% | 0.0% |

| No. | Rehabilitation | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 19 | Mesotherapy is applicable in individual rehabilitation programs | Q6, Q7 | Ib | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 95.0% | 5.0% | 0.0% |

| 20 | Mesotherapy is applicable in Sports and Exercise Medicine | Q6, Q7, Q8 | IIb | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 93.3% | 6.7% | 0.0% |

| 21 | Mesotherapy applied in Sports and Exercise Medicine must take anti- doping regulations into account | Q8 | IV | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 90.8% | 9.2% | 0.0% |

| Reference | Disease | N of Pts | Follow-Up | Number of Sessions | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [75] | post traumatic pain | 133 | 4 months | 1–4 sessions | Positive efficacy/safety; functional recovery of sporting competitive activity in shorter time than conventional therapies |

| [76] | pubic myoenthesitis | 256 | 6 months | from 2 to 5 sessions at 10–20 days intervals | Complete functional recovery after 4 sessions |

| [77] | acute lumbo sciatic pain in athletes | 20 | 4 months | 2–6 sessions | Pain reduction and functional recovery in 90% of patients |

| [78] | patellar tendonitis | 126 | 1 month | weekly sessions | 85% of patients reach complete pain relief (from 1 to 4 sessions) |

| [79] | ileo-tibial band friction syndrome | 40 | 3 months | weekly sessions | Pain relief in 55% of patients after 2 sessions; 97.5% after 3 sessions |

| [80] | myoenthesitis of the leg | 203 | 2 months | sessions at 7–8 days intervals | 60.8% of patients reach complete recovery with 1 session; 96,6% of patients reach complete recovery with 3 sessions. Mesotherapy was more effective for patients with recent pain. |

| [81] | rotator cuff tendinopathy | 145 | 12 weeks | from 4 to 9 | Reduction in pain, improvement in functioning |

| [82] | achilles tendonitis | 40 | 12 weeks | 4 weekly sessions | Pain reduction |

| No. | Chronic Venous Disease and Its Complications | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 22 | Mesotherapy is applicable in Chronic Venous Disease for the management of signs and symptoms, to limit its evolution and prevent complications | Q9 | III | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 84.9% | 15.1% | 0.0% |

| 23 | Mesotherapy is applicable in the management of fibro-sclerotic edematous panniculopathy (PEFS) | Q9, Q12 | IIb | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 81.5% | 18.5% | 0.0% |

| Dermatological Disorder |

|---|

| Alopecia |

| Cystic acne |

| Keloid |

| Cyst suppurated |

| Suppurative hydrosadenitis |

| Psoriasis |

| Ring granuloma |

| Foreign body granuloma |

| Lichen planus |

| Neurodermatitis and prurigo |

| Postscabular nodules |

| Warts |

| Benign lymphocytic infiltration |

| Cutaneous or discoid lupus |

| Lupic panniculitis |

| Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

| Eczema |

| Vitiligo |

| Lipoid necrobiosis |

| Pretibial myxedema |

| Cutaneous neoplasms |

| No. | Dermatology | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 24 | Mesotherapy is applicable in the management of some dermatological conditions | Q10, Q12 | III | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 84.0% | 16.0% | 0.0% |

| 25 | Mesotherapy represents an option in the treatment of alopecia | Q10 | Ia | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 78.2% | 20.2% | 1.7% |

| 26 | Mesotherapy represents an alternative or combination therapy in the treatment of melasma in patients refractory to first line therapy | Q10 | Ia | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 62.2% | 36.1% | 1.7% |

| No. | Mesotherapy in Skin Aging | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 27 | The blemish must be framed from a medical point of view in order to identify the rationale for treatment with mesotherapy | Q11, Q12 | IV | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 81.5% | 18.5% | 0.0% |

| 28 | Mesotherapy can be considered in the management of some blemishes if the goal of treatment is rational and if the patient shares the risk/benefit | Q11, Q12 | IV | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 82.4% | 16.8% | 0.8% |

| No. | Contraindications and Risk Management | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 29 | Mesotherapy must be performed by medical personnel and cannot be delegated to another healthcare professional | Q12, Q18 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 98.3% | 1.7% | 0.0% |

| 30 | Mesotherapy must be performed in patients who have undergone a medical examination from whicha rationale in favor of this treatment has emerged | Q12, Q18 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 31 | Mesotherapy must not be applied in subjects with absolute contraindications due to the technique or the injected product | Q17 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 99.2% | 0.8% | 0.0% |

| 32 | Mesotherapy must be performed in a suitable environment to guarantee asepsis and infection prevention standards | Q12, Q18 | IV | 5.0 ± 02 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 33 | Every adverse event must be recorded in the patient’s medical record and communicated to the health authorities according to current regulations | Q19 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 98.3% | 1.7% | 0.0% |

| No. | Scientific Research | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 34 | The use of the superficial infiltration technique applied to the oral mucosa (known as “oral mesotherapy”) has yielded promising data, but while awaiting further studies, the patients should be informed that its clinical application is experimental | Q13, Q22 | IV | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 63.9% | 33.6% | 2.5% |

| No. | Combination with Other Treatment Strategies and Treatment Algorithms | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 35 | Mesotherapy is applicable in the treatment path of patients and also in combination with other treatments | Q14 | III | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 36 | The treatment algorithm, in each area of application of mesotherapy, must consider the clinical response | Q15 | IIb | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 99.2% | 0.8% | 0.0 |

| 37 | Mesotherapy must be applied in a personalized treatment path, after a diagnosis and an accurate pharmacological, allergy, and pathological history | Q16; Q18, Q12 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 38 | Mesotherapy can be suggested exclusively to patients who have undergone a medical examination from which a rationale in favor of localized treatment has emerged | Q16, Q18 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 98.3% | 0.8% | 0.8% |

| 39 | In the individualized treatment path, mesotherapy can be used in combination with other therapies, pharmacological or non-pharmacological, or alone when other options with proven efficacy have failed or cannot be used, or there are no other therapeutic options | Q16; Q3 | IV | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 97.5% | 2.5% | 0.0% |

| No. | Ethics | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 40 | Before introducing mesotherapy into the individual treatment path, the doctor must explain its advantages and limitations, specify the product or products used, and obtain written informed consent | Q18 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 99.2% | 0.8% | 0.0% |

| 41 | Information documents provided to the patient to obtain informed consent must be based on current guidelines | Q18 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 96.6% | 2.5% | 0.8% |

| 42 | It is recommended to fill in the clinical record with the diagnosis, products used and their quantity injected, number of sessions, and results obtained | Q19 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 43 | Mesotherapy must be considered like any other off-label therapy even in minor patients, when the product, the route of administration, and the age of the patient do not fall within the authorization of the injected drug | Q20 | IV | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 92.4% | 6.7% | 0.8% |

| 44 | The teaching and updating of mesotherapy must be based on current guidelines | Q21 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 99.2% | 0.0% | 0.8% |

| Preclinical Research |

| 1. Dose (tissue) effect curve of the drug injected via ID |

| 2. Role of the dermis (dermal cells) in the clinical response |

| Clinical Research |

| 1. Injection depth |

| 2. Comparison of drug vs. combination of drugs |

| 3. Pharmacodynamic differences between ID and IV routes |

| 4. Cost/benefit in the various application areas (pain, MVC, dermo-aesthetic) |

| 5. Role of the ID pathway in vaccination |

| Heath Technology Assessment |

| 1. Economic impact of mesotherapy compared to other therapies |

| 2. Quality of life |

| 3. Patient acceptability |

| 4. Efficiency for the Healthcare System Clinical-organizational |

| Audit |

| 1. Efficiency in diagnostic, therapeutic and healthcare pathways |

| 2. Update of the guidelines |

| No. | Scientific research | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 45 | Researchers are recommended to draw up protocols useful for a better understanding of the mechanism of action and the role of mesotherapy in treatment pathways | Q22 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 99.2% | 0.8% | 0.0% |

| 46 | Clinicians are recommended to publish data relating to mesotherapy with a description of the technique used (depth of injection, number of micro-injections, treatment area, quantity of drug injected, number and frequency of sessions) and use methods of collecting results according to validated methodologies | Q22 | IV | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| No. | Patient’s Recommendation | Rif Question | AHCPR | Mean ± SD | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Abstained | Disagreement | |||||

| 47 | Patients’ suggestions must be considered in the drafting and periodic revision of the mesotherapy guideline | Q23 | IV | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 79.8% | 16.0% | 4.2% |

| 48 | Mesotherapy for analgesic purposes must be integrated into the individual path of care and assistance of the individual patient | Q23, Q6 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 49 | The patient has the right to be subjected to mesotherapy based on scientific evidence | Q23 | IV | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 99.2% | 0.0% | 0.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mammucari, M.; Russo, D.; Maggiori, E.; Rossi, M.; Lugli, M.; Marzo, R.D.; Migliore, A.; Leone, R.; Koszela, K.; Varrassi, G.; et al. International Consensus Guidelines on the Safe and Evidence-Based Practice of Mesotherapy: A Multidisciplinary Statement. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134689

Mammucari M, Russo D, Maggiori E, Rossi M, Lugli M, Marzo RD, Migliore A, Leone R, Koszela K, Varrassi G, et al. International Consensus Guidelines on the Safe and Evidence-Based Practice of Mesotherapy: A Multidisciplinary Statement. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134689

Chicago/Turabian StyleMammucari, Massimo, Domenico Russo, Enrica Maggiori, Marco Rossi, Marzia Lugli, Raffaele Di Marzo, Alberto Migliore, Raimondo Leone, Kamil Koszela, Giustino Varrassi, and et al. 2025. "International Consensus Guidelines on the Safe and Evidence-Based Practice of Mesotherapy: A Multidisciplinary Statement" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134689

APA StyleMammucari, M., Russo, D., Maggiori, E., Rossi, M., Lugli, M., Marzo, R. D., Migliore, A., Leone, R., Koszela, K., Varrassi, G., & on behalf of the International Expert Panel. (2025). International Consensus Guidelines on the Safe and Evidence-Based Practice of Mesotherapy: A Multidisciplinary Statement. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134689