Reconstruction of the Vulva and Perineum—Comparison of Surgical Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Surgical Methods for Perineal and Vulvar Reconstruction

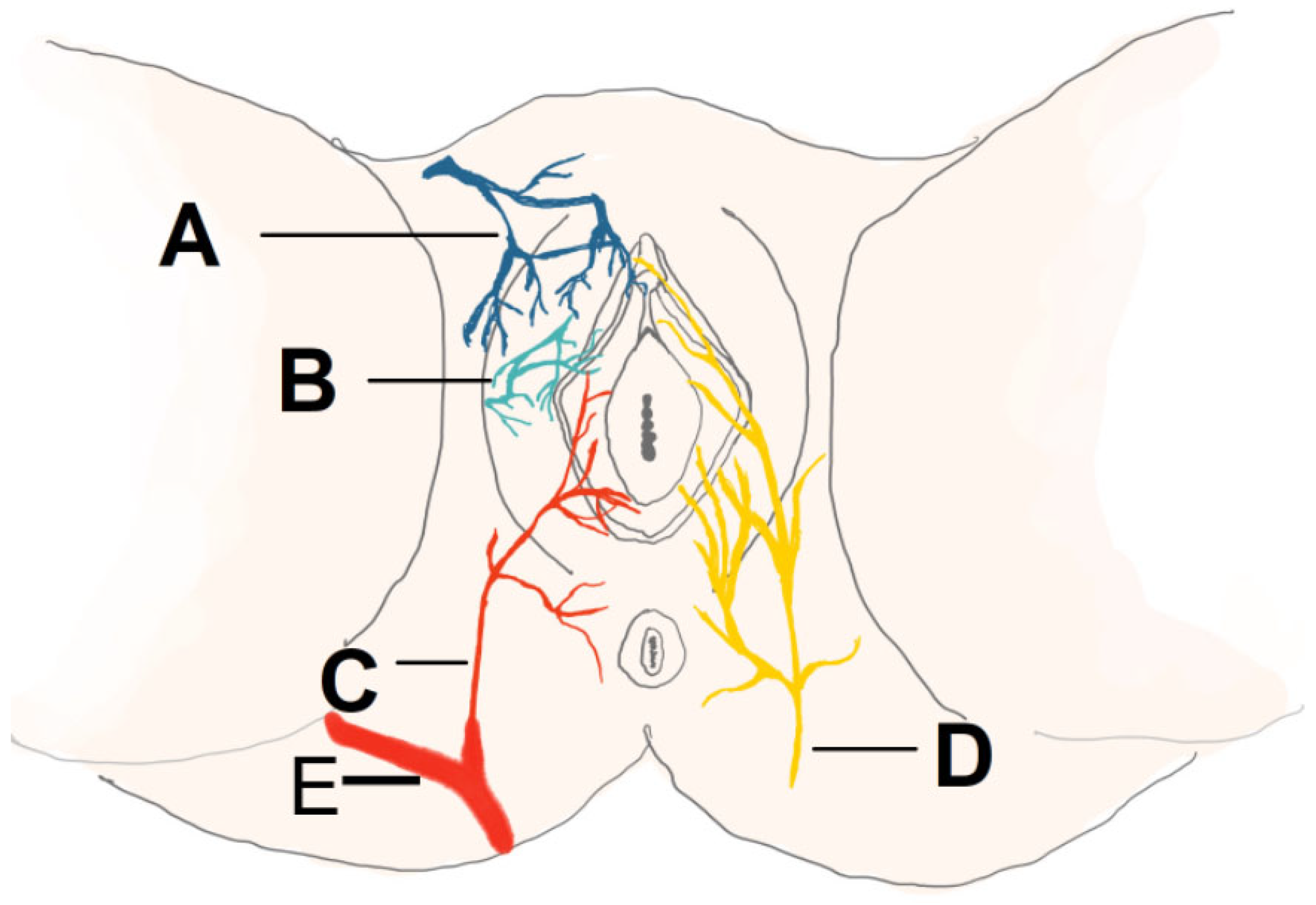

2.1. Sensate Gluteal Fold Flaps

2.2. Triple Flap Technique

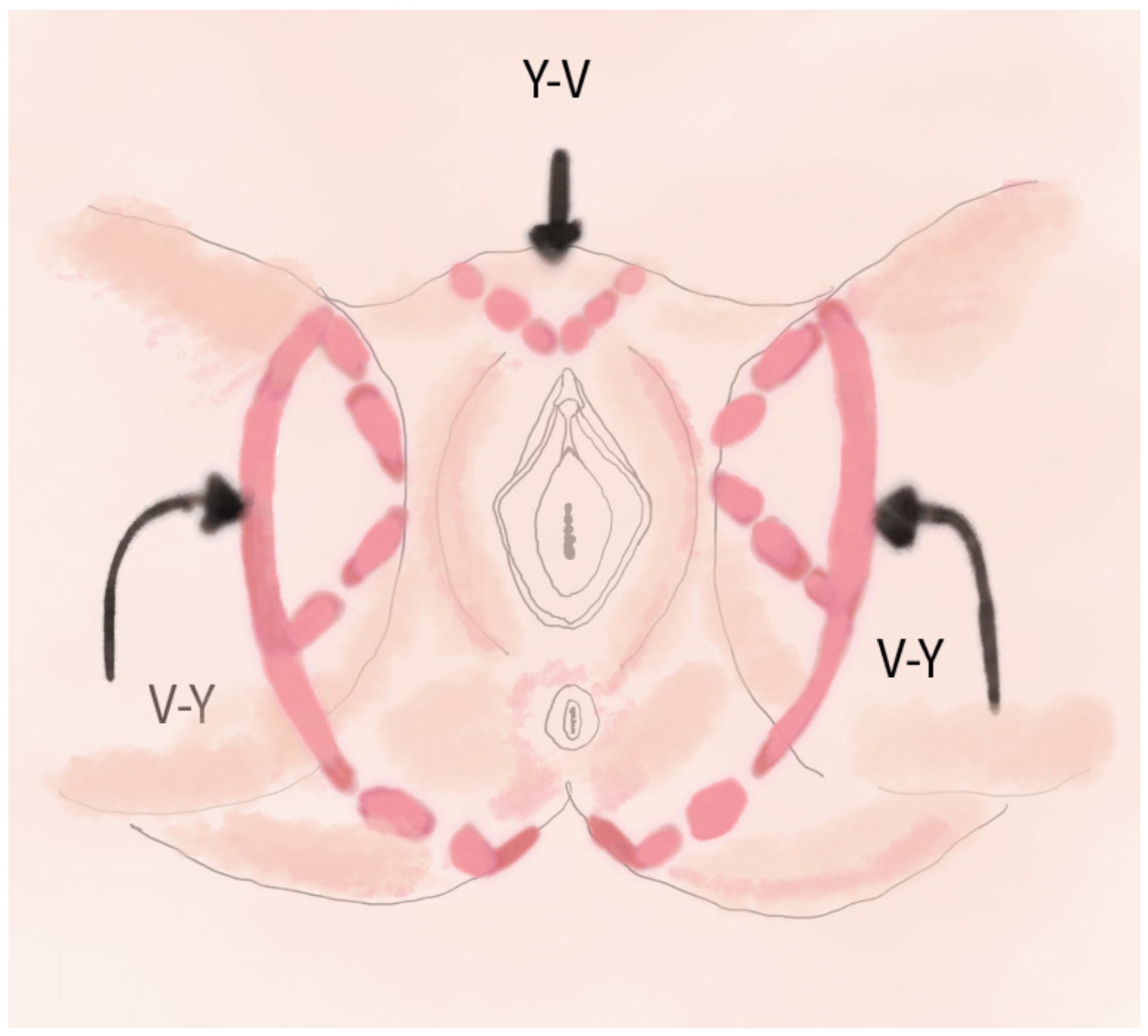

2.3. V-Y Fasciocutaneous Advancement Flaps

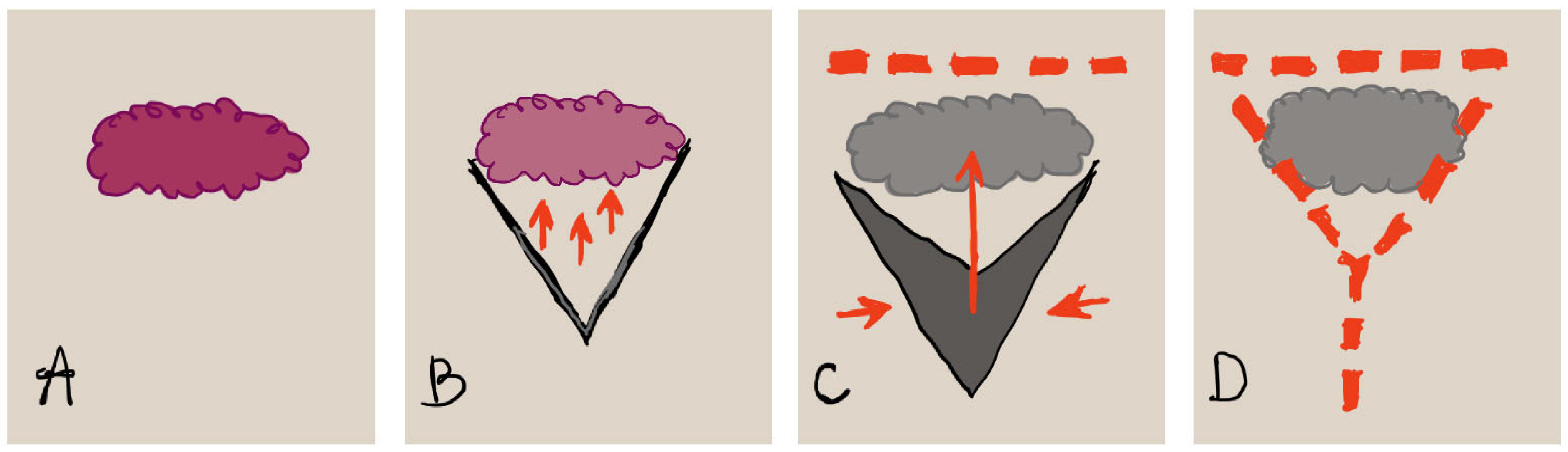

2.4. Keystone Perforator Island Flaps

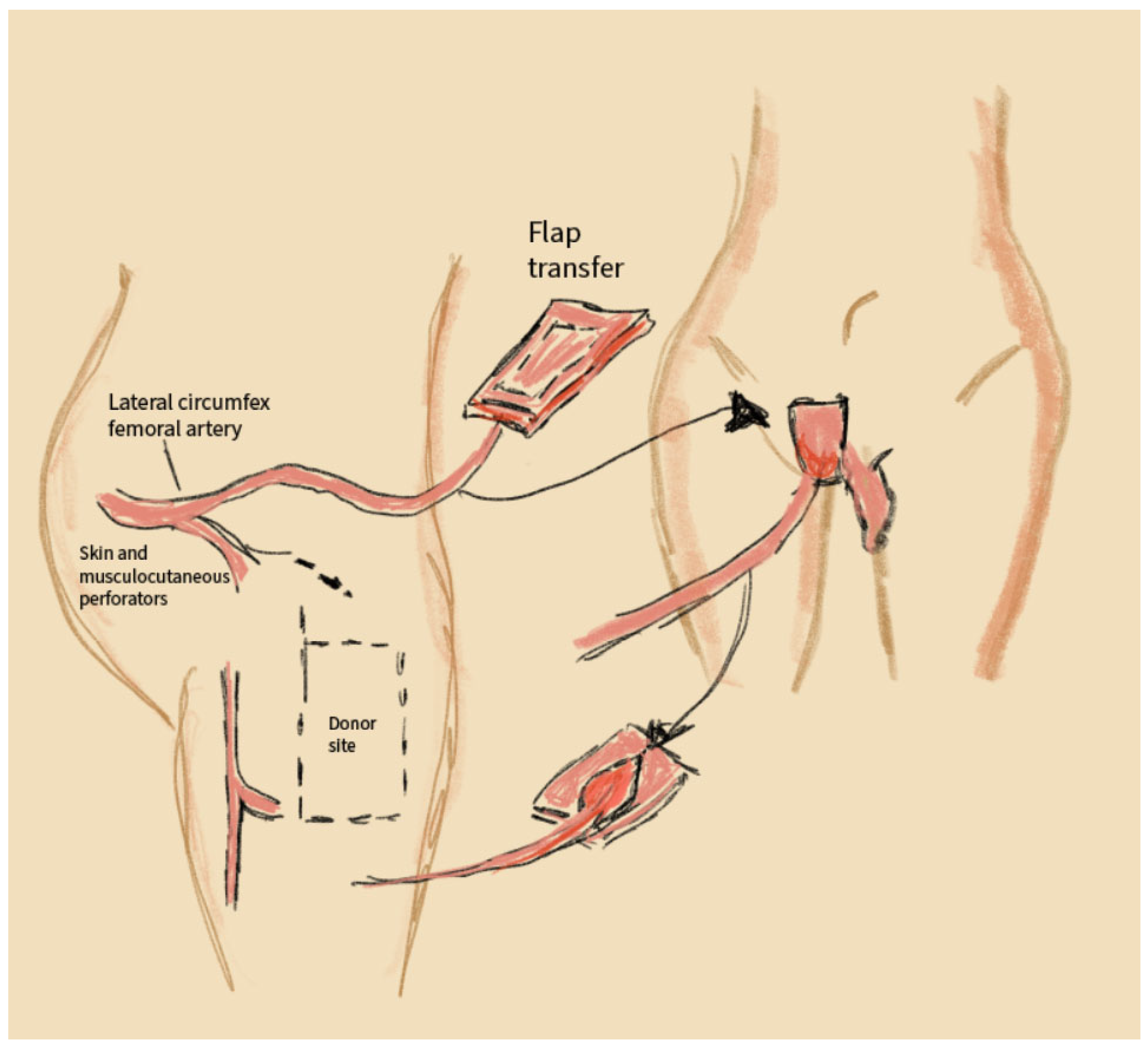

2.5. Anterolateral Thigh (ALT) Flaps

2.6. VRAM Flap (Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous Flap)

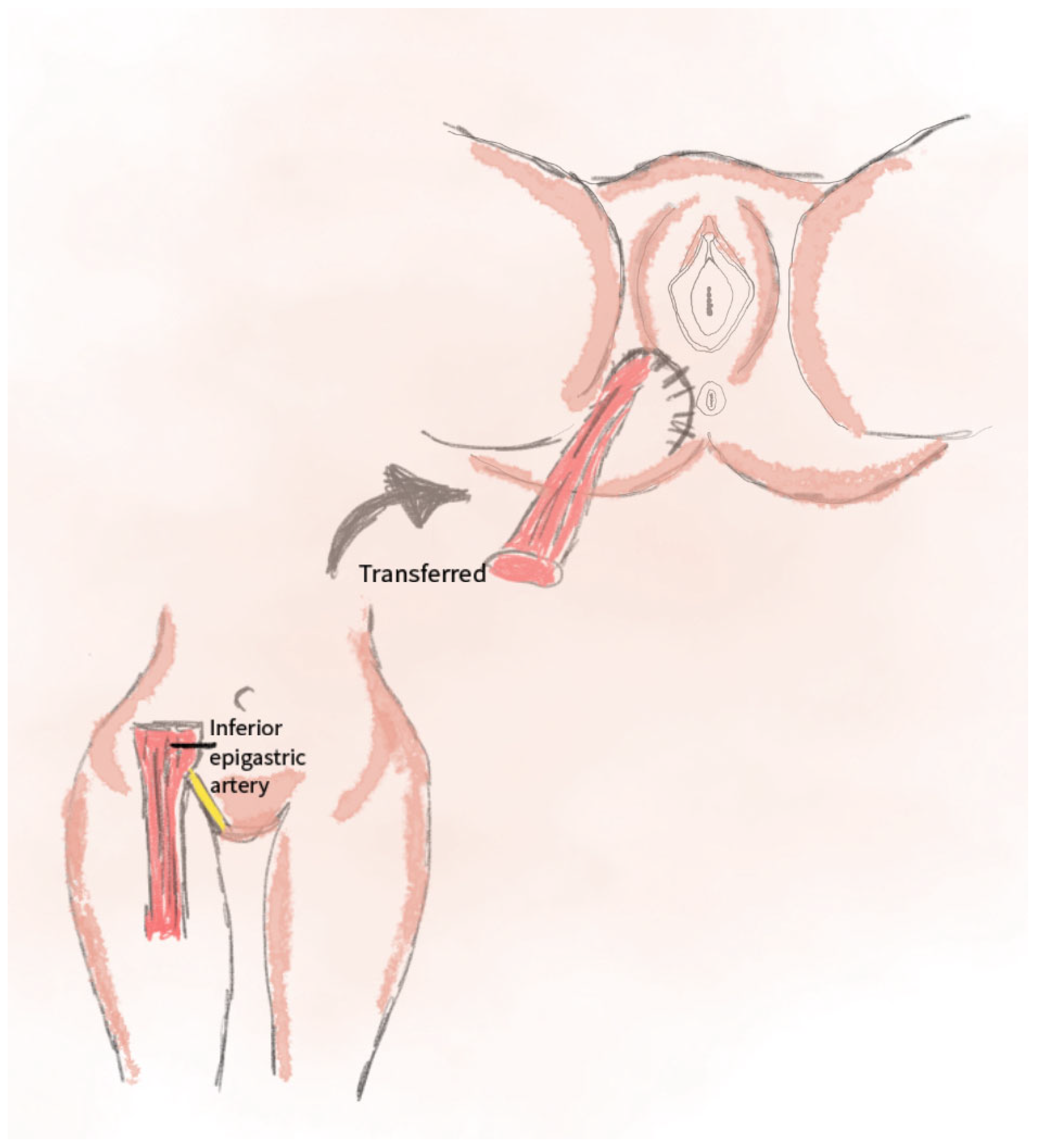

2.7. The Gracilis Flap

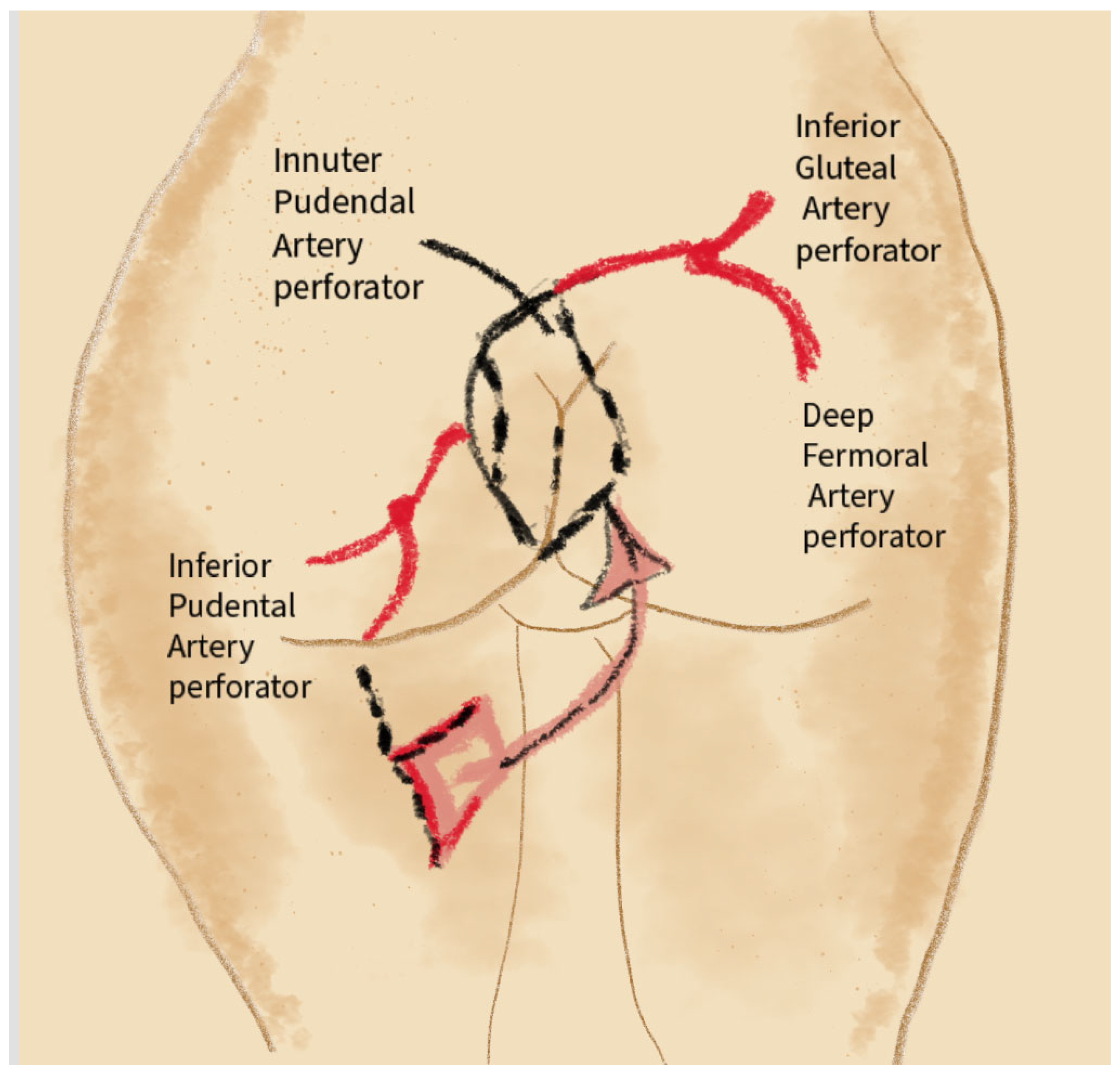

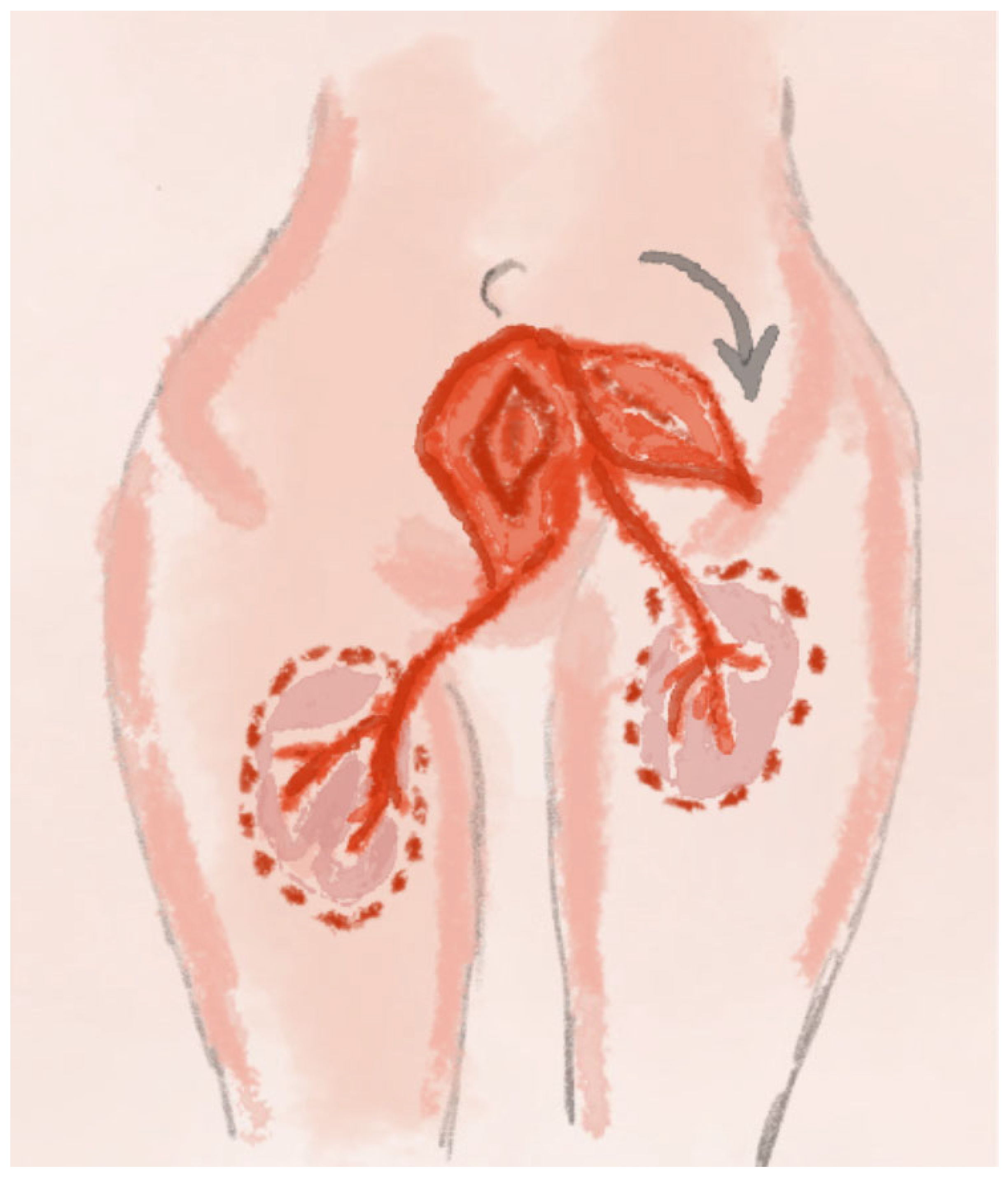

2.8. PAP Perforator Flap Technique

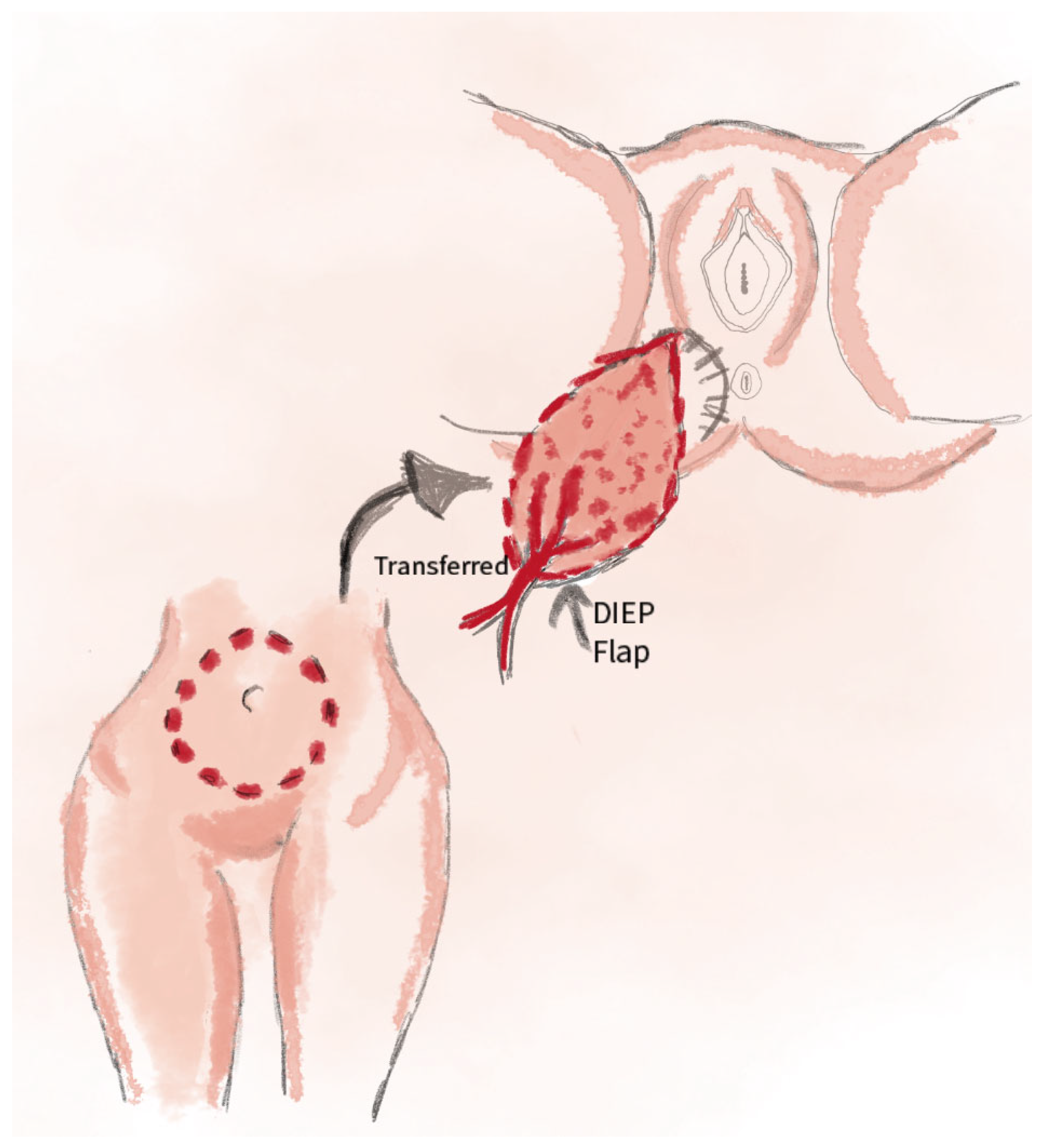

2.9. DIEP Perforator Flap Technique

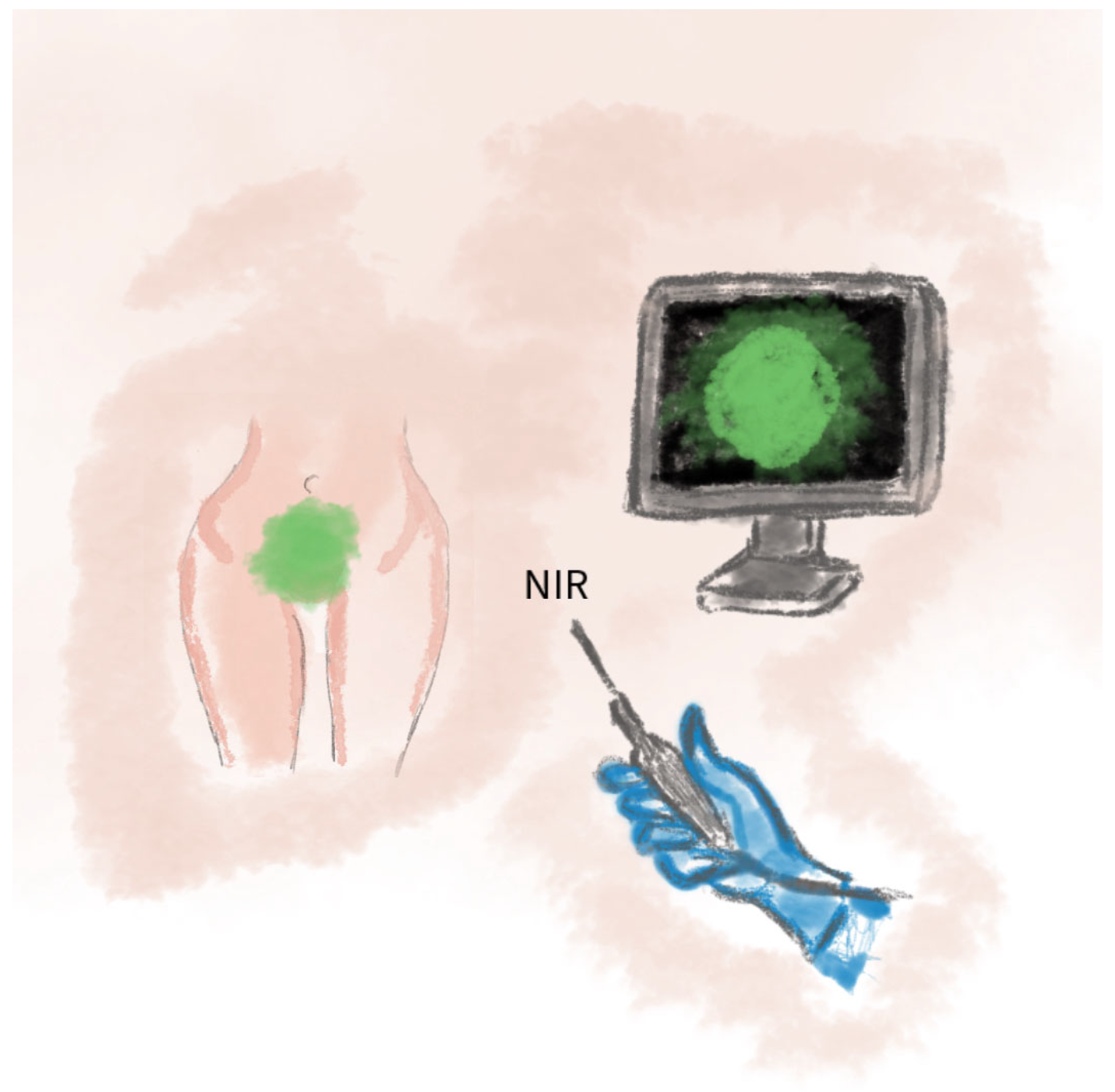

2.10. Application of ICG Technique in Vulvar and Perineal Reconstruction

2.11. Robot-Assisted Flap Harvesting Technique

3. Surgical Outcomes of Vulvar and Perineal Reconstruction: A Comparative Analysis of Techniques

4. Challenges and Possible Complications of Reconstruction Methods

4.1. Complications Related to the Proximity of Blood Vessels

4.2. Complications Depending on the Method of Reconstruction Used

4.3. Sensate Gluteal Fold Flaps

4.4. V-Y Fasciocutaneous Advancement Flaps

4.5. Triple Flap Technique (Triple V-Y Flap)

4.6. Keystone Flaps (Keystone Perforator Island Flaps)

4.7. Anterolateral Thigh Flap (ALT Flap)

4.8. Gracilis Flap

4.9. VRAM

4.10. PAP Flap (Profunda Artery Perforator Flap)

4.11. DIEP Flap (Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap)

4.12. ICG-Guided Reconstruction (Indocyanine Green Fluoroscence Imaging)

4.13. Robot-Assisted Flap Harvesting

4.14. Anatomical Proximity and Risk of Complications

5. The Role of Mental Health in Gynecological Treatment

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions and Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merlo, S. Modern treatment of vulvar cancer. Radiol. Oncol. 2020, 54, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Smith, M.; Barlow, E.; Coffey, K.; Hacker, N.; Canfell, K. Vulvar cancer in high-income countries: Increasing burden of disease. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuijs, N.B.; van Beurden, M.; Bruggink, A.H.; Steenbergen, R.D.M.; Berkhof, J.; Bleeker, M.C.G. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: Incidence and long-term risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satmary, W.; Holschneider, C.H.; Brunette, L.L.; Natarajan, S. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: Risk factors for recurrence. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigby, S.M.; Eva, L.J.; Fong, K.L.; Jones, R.W. The Natural History of Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia, Differentiated Type: Evidence for Progression and Diagnostic Challenges. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2016, 35, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallio, N.; Preti, M.; Jones, R.W.; Borella, F.; Woelber, L.; Bertero, L.; Urru, S.; Micheletti, L.; Zamagni, F.; Bevilacqua, F.; et al. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia long-term follow up and prognostic factors: An analysis of a large historical cohort. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2024, 103, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, D.; Yeo, H.; Park, H. Vulvar Reconstruction Using Keystone Flaps Based on the Perforators of Three Arteries. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2022, 49, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, M.H.M.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Mahner, S.; Mirza, M.R.; Fischerová, D.; Zapardiel, I. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer-Update 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restaino, S.; Pellecchia, G.; Arcieri, M.; Bogani, G.; Taliento, C.; Greco, P.; Driul, L.; Chiantera, V.; De Vincenzo, R.P.; Garganese, G.; et al. Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancers: A Systematic Comparison of International Guidelines (NCCN-ASCO-ESGO-BGCS-IGCS-FIGO-French Guidelines-RCOG). Cancers 2025, 17, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caretto, A.A.; Servillo, M.; Tagliaferri, L.; Lancellotta, V.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Garganese, G.; Scambia, G.; Gentileschi, S. Secondary post-oncologic vulvar reconstruction—A simplified algorithm. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1195580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, B.; Mueller, M.D.; Cignacco, E.L.; Eicher, M. Period prevalence and risk factors for postoperative short-term wound complications in vulvar cancer: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2010, 20, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorney, K.M.; Growdon, W.B.; Clemmer, J.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Hall, T.R.; Diver, E.; Boruta, D.; Del Carmen, M.G.; Goodman, A.; Schorge, J.O.; et al. Patient, treatment and discharge factors associated with hospital readmission within 30days after surgery for vulvar cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 144, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposio, E.; Moioli, M.; Raposio, G.; Spinaci, S.; Cagnacci, A. Perforator flaps for vulvar reconstruction: Basic principles. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022076. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.K.; Kang, G.C.; Tay, E.H.; Por, Y.C. Subunit principle of vulvar reconstruction: Algorithm and outcomes. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2014, 41, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentileschi, S.; Servillo, M.; Garganese, G.; Fragomeni, S.; De Bonis, F.; Scambia, G.; Salgarello, M. Surgical therapy of vulvar cancer: How to choose the correct reconstruction? J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, H.; Mikkola, A.; Nyberg, R.H.; Vuento, M.H.; Kaartinen, I.; Kuoppala, T. Reconstruction of the vulva with sensate gluteal fold flaps. Scand. J. Surg. 2013, 102, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelides, N.M.; Davies, R.J.; Fearnhead, N.S.; Malata, C.M. The gluteal fold flap: A versatile option for perineal reconstruction following anorectal cancer resection. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013, 66, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.; Yokogawa, H.; Sato, T.; Hirokawa, E.; Ichioka, S.; Nakatsuka, T. Gluteal fold flap for pelvic and perineal reconstruction following total pelvic exenteration. JPRAS Open. 2019, 19, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, I.; Nakanishi, H.; Nagae, H.; Harada, H.; Sedo, H. The gluteal-fold flap for vulvar and buttock reconstruction: Anatomic study and adjustment of flap volume. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.; Miyamoto, S.; Kitamura, Y.; Mito, D.; Okazaki, M. Secondary Vulvar Reconstruction Using Bilateral Gluteal Fold Flaps after Radical Vulvectomy with Direct Closure. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2021, 9, e3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercut, R.; Sinna, R.; Vaucher, R.; Giroux, P.A.; Assaf, N.; Lari, A.; Dast, S. Triple flap technique for vulvar reconstruction. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2018, 63, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.W.; Chang, H.; Kwon, S.T. Three-Directional Reconstruction of a Massive Perineal Defect after Wide Local Excision of Extramammary Paget’s Disease. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2016, 43, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazbeck, S.; Luks, F.I.; St-Vil, D. Anterior perineal approach and three-flap anoplasty for imperforate anus: Optimal reconstruction with minimal destruction. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1992, 27, 190–194, discussion 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carramaschi, F.; Ramos, M.L.; Nisida, A.C.; Ferreira, M.C.; Pinotti, J.A. V—Y flap for perineal reconstruction following modified approach to vulvectomy in vulvar cancer. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 1999, 65, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, L.J.; Lu, X.M.; Rao, Q.X.; Lu, H.W.; Lin, Z.Q. A modified triple incision technique for women with locally advanced vulvar cancer: A description of the technique and outcomes. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 164, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, V.; Bracchi, C.; Cigna, E.; Domenici, L.; Musella, A.; Giannini, A.; Lecce, F.; Marchetti, C.; Panici, P.B. Vulvo-vaginal reconstruction after radical excision for treatment of vulvar cancer: Evaluation of feasibility and morbidity of different surgical techniques. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 26, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conri, V.; Casoli, V.; Coret, M.; Houssin, C.; Trouette, R.; Brun, J.L. Modified Gluteal Fold V-Y Advancement Flap for Reconstruction After Radical Vulvectomy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbola, S.O.; Pisani, A.; Sahnan, K.; Tozer, P.; Ellul, P.; Warusavitarne, J. Medical and surgical management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2018, 31, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, L.C.; Maas, T.M.; Baka, N.; Mercier, R.J.; Greaney, P.J.; Rosenblum, N.G.; Kim, C.H. Utilizing V-Y fasciocutaneous advancement flaps for vulvar reconstruction. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 26, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti Panici, P.; Di Donato, V.; Bracchi, C.; Marchetti, C.; Tomao, F.; Palaia, I.; Perniola, G.; Muzii, L. Modified gluteal fold advancement V-Y flap for vulvar reconstruction after surgery for vulvar malignancies. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fin, A.; Rampino Cordaro, E.; Guarneri, G.F.; Revesz, S.; Vanin, M.; Parodi, P.C. Experience with gluteal V-Y fasciocutaneous advancement flaps in vulvar reconstruction after oncological resection and a modification to the marking: Playing with tension lines. Int. Wound J. 2019, 16, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiretti, M.; Corvetto, E.; Candotti, G.; Angioni, S.; Figus, A.; Mais, V. New Keystone flap application in vulvo-perineal reconstructive surgery: A case series. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 30, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behan, F.C.; Rozen, W.M.; Azer, S.; Grant, P. ‘Perineal keystone design perforator island flap’ for perineal and vulval reconstruction. ANZ J. Surg. 2012, 82, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Dorairajan, L.N.; Mehra, K.; Manikandan, R. Keystone Flaps in Urethroplasty: Reconstruction in a Complex Case of Panurethral Stricture Disease. Niger. Med. J. 2019, 60, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wagstaff, M.J.; Rozen, W.M.; Whitaker, I.S.; Enajat, M.; Audolfsson, T.; Acosta, R. Perineal and posterior vaginal wall reconstruction with superior and inferior gluteal artery perforator flaps. Microsurgery 2009, 29, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, A.; Umezawa, H.; Taga, M.; Ogawa, R. Vulvovaginal Reconstruction With a Modified Pedicled Anterolateral Thigh Flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2025, 13, e6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuli, J.N.; Hubner, M.; Martineau, J.; Oranges, C.M.; Guillier, D.; Raffoul, W.; di Summa, P.G. Impact of etiology leading to abdominoperineal resection with anterolateral thigh flap reconstruction: A retrospective cohort study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 127, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrault, D.; Kin, C.; Wan, D.C.; Kirilcuk, N.; Shelton, A.; Momeni, A. Pelvic/Perineal Reconstruction: Time to Consider the Anterolateral Thigh Flap as a First-line Option? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2020, 8, e2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Raffoul, W.; Piaget, F.; Egloff, D.V. Anterolateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap in the difficult perineogenital reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2000, 105, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubietz, R.G.; Jakubietz, M.G.; Meffert, R.H.; Holzapfel, B.; Schmidt, K. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flap reconstruction in the region of the lower abdomen, groin, perineum, and hip. Oper. Orthop. Traumatol. 2022, 34, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Qiao, Q.; Zhao, R.; Song, K.; Long, X. Anterolateral thigh flap-based reconstruction for oncologic vulvar defects. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 127, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.E.; Gündeslioglu, A.O.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A. Outcomes of immediate vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap reconstruction for irradiated abdominoperineal resection defects. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2008, 206, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, D.M.; Patel, N.B.; Zeiderman, M.R.; Wong, M.S. The Vertical Rectus Abdominis Musculocutaneous Flap As a Versatile and Viable Option for Perineal Reconstruction. Eplasty 2017, 17, ic2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radwan, R.W.; Tang, A.M.; Harries, R.L.; Davies, E.G.; Drew, P.; Evans, M.D. Vertical rectus abdominis flap (VRAM) for perineal reconstruction following pelvic surgery: A systematic review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2021, 74, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseme, E.A.; Scampa, M.; Viscardi, J.A.; Ebai, M.; Kalbermatten, D.F.; Oranges, C.M. Surgical Outcomes of VRAM vs. Gracilis Flaps in Vulvo-Perineal Reconstruction Following Oncologic Resection: A Proportional Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, F.A.; Martijnse, I.S.; Traa, M.J.; Boll, D.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.; de Hingh, I.H.; Rutten, H.J. Dynamic article: Vaginal and perineal reconstruction using rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap in surgery for locally advanced rectum carcinoma and locally recurrent rectum carcinoma. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013, 56, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, U.; Tak, A.; Barmon, D.; Begum, D. Vulvar reconstruction in post-RT case using the versatile VRAM flap: Reporting the rare extrapelvic approach. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e254773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faur, I.F.; Clim, A.; Dobrescu, A.; Prodan, C.; Hajjar, R.; Pasca, P.; Capitanio, M.; Tarta, C.; Isaic, A.; Noditi, G.; et al. VRAM Flap for Pelvic Floor Reconstruction after Pelvic Exenteration and Abdominoperineal Excision. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeless, C.R.; McGibbon, B.; Dorsey, J.H.; Maxwell, G.P. Gracilis myocutaneous flap in reconstruction of the vulva and female perineum. Obstet. Gynecol. 1979, 54, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.G.W.; Crigger, C.B.; Suresh, V.; Haffar, A.; Sholklapper, T.N.; Nasr, I.W.; Gearhart, J.P.; Yang, R.; Redett, R.J.I. Interposing Rectus and Gracilis Muscle Flaps for Pelvic Reconstruction in Bladder Exstrophy after Bladder Neck Closure. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 154, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcieri, M.; Restaino, S.; Rosati, A.; Granese, R.; Martinelli, C.; Caretto, A.A.; Cianci, S.; Driul, L.; Gentileschi, S.; Scambia, G.; et al. Primary flap closure of perineal defects to avoid empty pelvis syndrome after pelvic exenteration in gynecologic malignancies: An old question to explore a new answer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 107278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, H.E.; Jessop, Z.M.; Di Candia, M.; Simcock, J.; Durrani, A.J.; Malata, C.M. An algorithmic approach to perineal reconstruction after cancer resection--experience from two international centers. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 71, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.; Roos, J.; Jakse, G.; Pallua, N. Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of recto-urethral and rectovaginal fistulas: A retrospective analysis of 35 cases. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2009, 62, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.J.; Karir, A.; Ramji, M.; Allen, M.; Bain, J.R.; Avram, R.; Jarmuske, M. Surgical outcomes of VRAM versus gracilis flaps for the reconstruction of pelvic defects following oncologic resection. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2019, 72, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.J.; Chang, N.J.; Chou, H.H.; Wu, C.W.; Abdelrahman, M.; Chen, H.Y.; Cheng, M.H. Pedicle perforator flaps for vulvar reconstruction--new generation of less invasive vulvar reconstruction with favorable results. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Iyer, M.K.; Stuart, P.E.; Swindell, W.R.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Tejasvi, T.; Sarkar, M.K.; Li, B.; Ding, J.; Voorhees, J.J.; et al. Analysis of long non-coding RNAs highlights tissue-specific expression patterns and epigenetic profiles in normal and psoriatic skin. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arquette, C.; Wan, D.; Momeni, A. Perineal Reconstruction with the Profunda Artery Perforator Flap. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2022, 88, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosutic, D.; Tsapralis, N.; Gubbala, P.; Smith, M. Reconstruction of critically-sized perineal defect with perforator flap puzzle technique: A case report. Case Rep. Plast. Surg. Hand. Surg. 2019, 6, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, O.; Kapur, S.; Shaikh, I.; Rosich-Medina, A.; Haywood, R. The combined use of pedicled profunda artery perforator and bilateral gracilis flaps for pelvic reconstruction: A cohort study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2021, 74, 2654–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, M.; Mota, R.; Paiva, V.; Duarte, A.; Costa, J.; Costa, A. Recurrence of vulvar carcinoma: A multidisciplinary approach. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 29, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, G.; Gangloff, D.; Querleu, D.; Frigenza, M.; Torrent, J.J.; Picaud, L.; Gladieff, L.; Delannes, M.; Mery, E.; Boulet, B.; et al. Vaginal reconstruction with pedicled vertical deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (diep) after pelvic exenteration. A consecutive case series. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 138, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.R.; Ameet, H.; Li, X.F.; Lu, Q.; Wang, X.C.; Zeng, A.; Qiao, Q. Pedicled thinned deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap for perineal reconstruction: A preliminary report. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2011, 64, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pividori, M.; Gangloff, D.; Ferron, G.; Meresse, T.; Delay, E.; Rivoire, M.; Perez, S.; Vaucher, R.; Frobert, P. Outcomes of DIEP flap reconstruction after pelvic cancer surgery: A retrospective multicenter case series. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2023, 85, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Saint-Cyr, M. Split and thinned pedicle deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap for vulvar reconstruction. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2013, 29, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Reilly, F.; Epperlein, J.P.; Potter, S.; Cahill, R. Advancing indocyanine green fluorescence flap perfusion assessment via near infrared signal quantification. JPRAS Open 2024, 41, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sluis, W.B.; Bouman, M.B.; Al-Tamimi, M.; Meijerink, W.J.; Tuynman, J.B. Real-time indocyanine green fluorescent angiography in laparoscopic sigmoid vaginoplasty to assess perfusion of the pedicled sigmoid segment. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 967–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbes, L.A.; Hoveling, R.J.M.; Schmidt, L.R.; Berns, S.; Weixler, B. Objective Perfusion Assessment in Gracilis Muscle Interposition-A Novel Software-Based Approach to Indocyanine Green Derived Near-Infrared Fluorescence in Reconstructive Surgery. Life 2022, 12, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentea, R.M.; Halleran, D.R.; Ahmad, H.; Sanchez, A.V.; Gasior, A.C.; McCracken, K.; Hewitt, G.D.; Alexander, V.; Smith, C.; Weaver, L.; et al. Preliminary Use of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Angiography and Value in Predicting the Vascular Supply of Tissues Needed to Perform Cloacal, Anorectal Malformation, and Hirschsprung Reconstructions. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 30, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.A.; Monfardini, L.; Sozzi, G.; Armano, G.; Rosati, A.; Gueli Alletti, S.; Cosentino, F.; Ercoli, A.; Cianci, S.; Berretta, R. Subcutaneous Vulvar Flap Viability Evaluation With Near-Infrared Probe and Indocyanine Green for Vulvar Cancer Reconstructive Surgery: A Feasible Technique. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 721770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, R.; Shih, L.; Gimenez, A.; Bay, C.; Chai, C.Y.; Maricevich, M. Robotic Rectus Abdominis Harvest for Pelvic Reconstruction after Abdominoperineal Resection. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2023, 37, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, G.; Yıldızdal, S.; Güdeloğlu, A.; Selber, J. Robotic harvest of the free gracilis muscle flap. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2024, 90, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, T.W.; Balch, G.C.; Kehoe, S.M.; Margulis, V.; Saint-Cyr, M. Reconstruction of Large Perineal and Pelvic Wounds Using Gracilis Muscle Flaps. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 3738–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, A.A.; Goldman, J.; Kleban, S.; Lyons, M.; Brosious, J.; Bardakcioglu, O.; Baynosa, R.C. Reducing Complications and Expanding Use of Robotic Rectus Abdominis Muscle Harvest for Pelvic Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022, 150, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, M.; Pisters, L.L.; Klein, G.T.; Adelman, D.M.; Oates, S.D.; Butler, C.E.; Selber, J.C.M. Robotic Rectus Abdominis Muscle Flap following Robotic Extirpative Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021, 148, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiatrek, R.L.; Thomas, J.S.; Papaconstantinou, H.T. Perineal wound complications after abdominoperineal resection. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2008, 21, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, J.C.; Browning, K.K. Smoking, chronic wound healing, and implications for evidence-based practice. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2014, 41, 415–423, quiz E1–E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Jaraquemada, J.M.; García Mónaco, R.; Barbosa, N.E.; Ferle, L.; Iriarte, H.; Conesa, H.A. Lower uterine blood supply: Extrauterine anastomotic system and its application in surgical devascularization techniques. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangwi, A.A.; Ebasone, P.V.; Aroke, D.; Ngek, L.T.; Nji, A.S. Non-obstetric vulva haematomas in a low resource setting: Two case reports. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.K.; Choi, M.S.; Ahn, S.T.; Oh, D.Y.; Rhie, J.W.; Han, K.T. Gluteal fold V-Y advancement flap for vulvar and vaginal reconstruction: A new flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 118, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, L.; Guarneri, G.F.; Rampino Cordaro, E.; Bassini, D.; Revesz, S.; Borgna, G.; Parodi, P.C. Vulvar reconstruction using a “V-Y” fascio-cutaneous gluteal flap: A valid reconstructive alternative in post-oncological loss of substance. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010, 282, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez López, G.; Martínez Gil, S.; Zannin Ferrero, A.; Ramos Hernández, D.; Caicedo Páez, L.M. Vulvar Reconstruction with Keystone Flaps after Radical Vulvectomy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2024, 12, e5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behan, F.C. The Keystone Design Perforator Island Flap in reconstructive surgery. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, C.A.; Chang, J.; Henderson, J.T.; Hassouba, M.; Ashfaq, F.; Kostopoulos, E.; Konofaos, P. Keystone Flaps: Physiology, Types, and Clinical Applications. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 83, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelissier, P.; Gardet, H.; Pinsolle, V.; Santoul, M.; Behan, F.C. The keystone design perforator island flap. Part II: Clinical applications. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2007, 60, 888–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonetti, C.; Arleo, S.; Valdatta, L.; Faini, G. The Keystone Design Perforator Flap: A Flap to Simplify Complex Reconstructive Issues. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2024, 57 (Suppl. 1), S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, J.L.; Guidry, R.F.; Palines, P.A.; Dibbs, R.P.; Melancon, D.M.; Womac, D.J.; Stalder, M.W. The Vertical Profunda Artery Perforator Flap for Perineal Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2024, 93, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Hyakudomi, R.; Takai, K.; Taniura, T.; Uchida, Y.; Ishitobi, K.; Hirahara, N.; Tajima, Y. Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy with indocyanine green fluorescence imaging for a female adolescent with complete rectal prolapse: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziottin, A. Maintaining vulvar, vaginal and perineal health: Clinical considerations. Womens Health 2024, 20, 17455057231223716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baessler, K.; Schuessler, B. Childbirth-induced trauma to the urethral continence mechanism: Review and recommendations. Urology 2003, 62 (Suppl. 1), 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raef, H.S.; Elmariah, S.B. Vulvar Pruritus: A Review of Clinical Associations, Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Management. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 649402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, M.; Gath, D. Psychological aspects of gynaecological surgery. Baillieres Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1989, 3, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, M.; Obermair, A.; Cella, D.; Crandon, A.J.; Trimmel, M. Vulvar cancer patients’ quality of life: A qualitative assessment. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2004, 14, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortilla, S.; Pruneti, C.; Masellis, G.; Guidotti, S.; Caramuscio, C. Clinical-Psychological Aspects Involved in Gynecological Surgery: Description of Peri-Operative Psychopathological Symptoms and Illness Behavior. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2023, 16, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Seland, M.; Skrede, K.; Lindemann, K.; Skaali, T.; Blomhoff, R.; Bruheim, K.; Wisløff, T.; Thorsen, L. Distress, problems and unmet rehabilitation needs after treatment for gynecological cancer. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2022, 101, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, D.M.; Dakhil, R.; Lampe, B. Quality of life and sexual function after surgery in early stage vulvar cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, V.; Burke, J.P.; Condon, E.; Waldron, D.; Ajmal, N.; Deasy, J.; McNamara, D.A.; Coffey, J.C. Vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap and quality of life following abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer: A multi-institutional study. Tech. Coloproctol. 2014, 18, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, M.; Obermair, A.; Cella, D.; Perrin, L.C.; Nicklin, J.L.; Ward, B.G.; Crandon, A.J.; Trimmel, M. The functional assessment of cancer-vulvar: Reliability and validity. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 97, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Sensate Gluteal Fold Flaps [16]. | - Retained innervation in the flaps enables the restoration of sensory function. - The scar is located within the natural gluteal fold, improving aesthetic outcomes. - Minimized risk of necrosis due to the well-matched tissue profile for the perineal region. | - Not suitable for covering large defects. - Time-consuming and labor-intensive procedure. |

| Triple Flap Technique [21]. | - Allows complex reconstruction of large defects while maintaining function and aesthetics, without the need for distant flaps. - Combining flaps facilitates the precise adaptation of tissues to the defect. - Minimizes the risk of wound dehiscence. | - Prolonged operative time. - Increased risk of flap necrosis due to the complexity of the procedure. |

| V-Y Fasciocutaneous Advancement Flap [29]. | - Relatively simple technique requiring minimal donor-site intervention. - Ideal for smaller and superficial defects. - Minimal risk of donor-site complications. - Shorter operative and recovery times compared to other methods. - Maintains the anatomical and functional integrity of adjacent tissues. | - Restricted use for deep and large defects. - Inferior aesthetic results compared to more advanced methods. |

| Keystone Perforator Island Flaps [7]. | - Suitable for medium and large defects. - Faster procedure time with a low risk of flap necrosis. - Good vascularization provided by perforators from three arteries. - No need to create a separate donor site. | - Less effective for defects requiring a significant tissue volume. - Requires operator expertise in utilizing perforator flaps. |

| ALT Flap [38]. | - Provides a large amount of tissue, making it an ideal method for very large defects. - Minimal functional deficit at the donor site. - Can be used as either a free or pedicled flap. | - Longer surgical duration with microvascular requirements. - Requires an experienced operator. |

| VRAM [45]. | - Stable blood supply. - Capable of covering large and deep defects. - Provides good functional outcomes. | - Risk of complications at the donor site, such as abdominal hernia. - Potential impact on abdominal muscle functionality. |

| Gracilis Flap [45]. | - Simpler technique, suitable for smaller defects. - Lower risk of donor-site complications. - Shorter operative time. | - Restricted tissue volume for reconstruction. |

| PAP Flap [57]. | - Minimally invasive. - Flexible flap design. - Suitable for extensive tissue defects. | - Requires precise vascular imaging - Limited donor tissue volume in slender patients |

| DIEP Flap [61]. | - Preserves the rectus abdominis muscle. - Favorable aesthetic outcomes. - Covers large and deep defects. | - Prolonged operative time - Requires favorable abdominal anatomy |

| ICG Angiography [65]. | - Real-time tissue perfusion assessment. - Reduces the risk of flap necrosis. | - Requires specialized equipment - Risk of hypersensitivity reactions to indocyanine green |

| Robotic-Assisted Flap Harvesting [70]. | - High precision with minimal donor site trauma. - Satisfactory aesthetic outcomes. - Shorter hospitalization. | - High cost and limited availability - Requires an experienced surgical team |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jędrasiak, A.; Juniewicz, H.; Raczek, W.; Srokowska, A.; Kozłowski, M.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. Reconstruction of the Vulva and Perineum—Comparison of Surgical Methods. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134456

Jędrasiak A, Juniewicz H, Raczek W, Srokowska A, Kozłowski M, Cymbaluk-Płoska A. Reconstruction of the Vulva and Perineum—Comparison of Surgical Methods. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134456

Chicago/Turabian StyleJędrasiak, Anna, Honorata Juniewicz, Wiktoria Raczek, Alicja Srokowska, Mateusz Kozłowski, and Aneta Cymbaluk-Płoska. 2025. "Reconstruction of the Vulva and Perineum—Comparison of Surgical Methods" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134456

APA StyleJędrasiak, A., Juniewicz, H., Raczek, W., Srokowska, A., Kozłowski, M., & Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. (2025). Reconstruction of the Vulva and Perineum—Comparison of Surgical Methods. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134456