Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab and Vedolizumab Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy

3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Interventions

4. Outcome Measures

4.1. Primary Efficacy Outcomes

4.2. Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

4.3. Safety Outcomes

5. Evidence Synthesis and Quality Assessment

5.1. Study Selection

5.2. Data Extraction and Management

5.3. Quality Assessment

6. Data Synthesis and Measures of Treatment Effect

7. Results

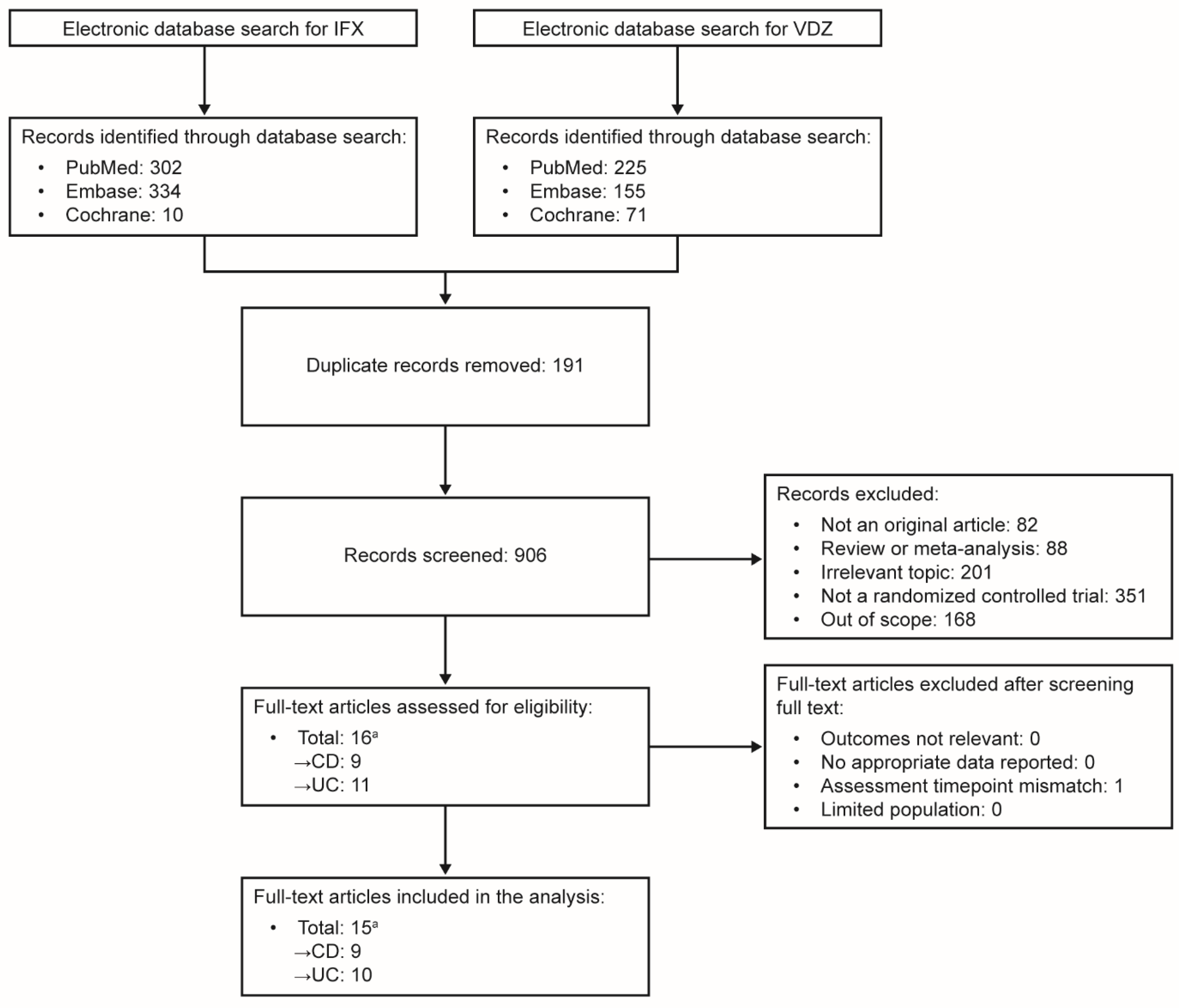

Search Results

8. Study Characteristics

8.1. Crohn’s Disease

8.2. Ulcerative Colitis

9. Risk of Bias in the Included Studies

10. Comparative Efficacy and Safety Between Treatments

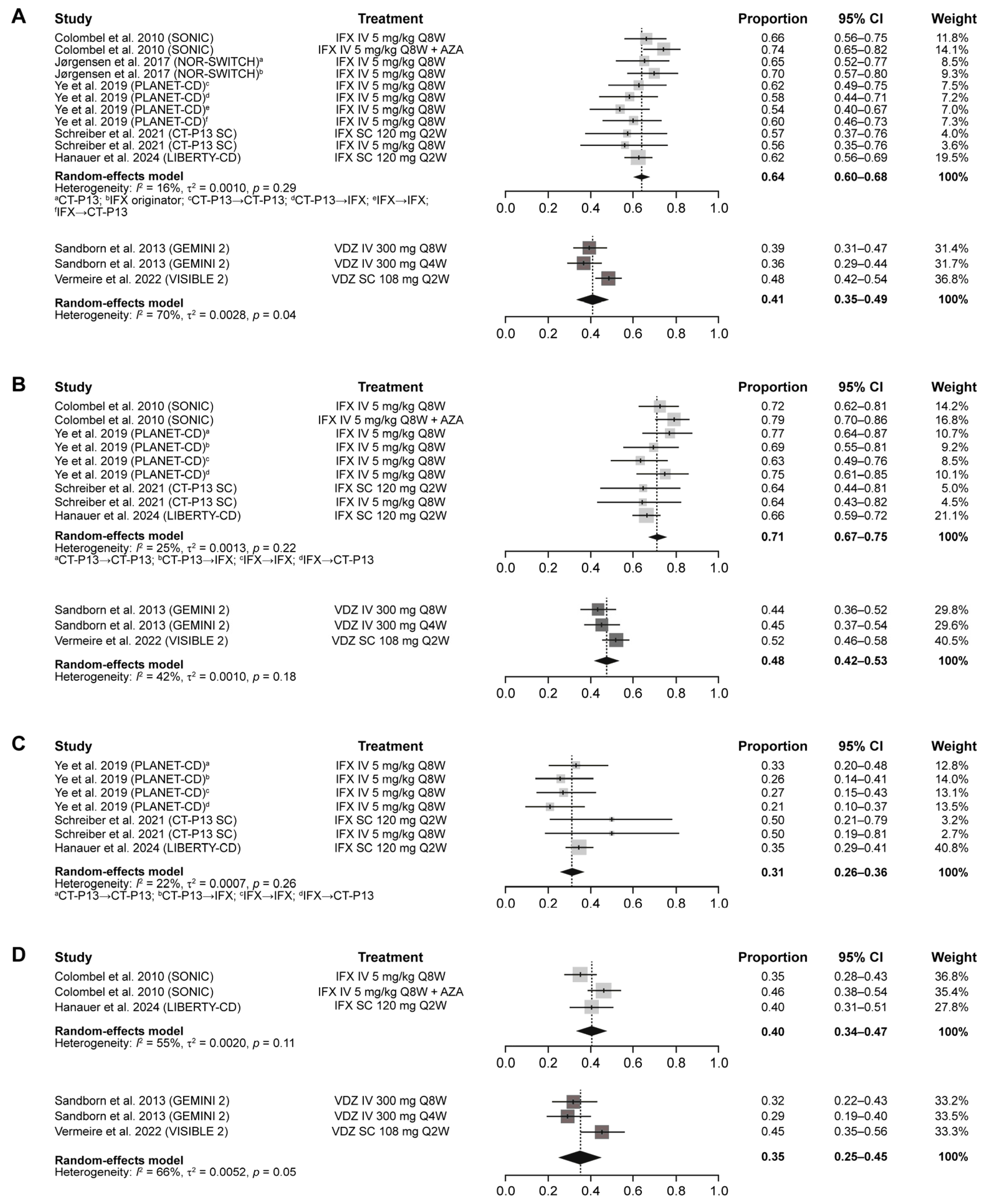

10.1. Efficacy Analyses

10.2. Sensitivity Analyses

10.3. Safety Analyses

11. Discussion

12. Future Perspectives

13. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: Medical treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Bonovas, S.; Doherty, G.; Kucharzik, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Raine, T.; Adamina, M.; Armuzzi, A.; Bachmann, O.; Bager, P.; et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: Medical treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Arkkila, P.; Armuzzi, A.; Danese, S.; Guardiola, J.; Jahnsen, J.; Lees, C.; Louis, E.; Lukas, M.; Reinisch, W.; et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of infliximab and vedolizumab therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Arkkila, P.; Armuzzi, A.; Danese, S.; Ferrante, M.; Jordi, G.; Jahnsen, J.; Louis, E.; Lukas, M.; Reinisch, W.; et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of subcutaneous infliximab and vedolizumab in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis included in randomised controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Entyvio Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/entyvio-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- European Medicines Agency. Remsima Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/remsima-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- US Food and Drug Administration. ZYMFENTRA Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/761358s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Takeda. Press Release: U.S. FDA Approves Subcutaneous Administration of Takeda’s ENTYVIO® (Vedolizumab) for Maintenance Therapy in Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis. Available online: https://www.takeda.com/newsroom/newsreleases/2023/US-FDA-Approves-Subcutaneous-Administration-of-Takeda-ENTYVIO-vedolizumab-for-Maintenance-Therapy-in-Moderately-to-Severely-Active-Ulcerative-Colitis/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Hanauer, S.B.; Sands, B.E.; Schreiber, S.; Danese, S.; Klopocka, M.; Kierkus, J.; Kulynych, R.; Gonciarz, M.; Soltysiak, A.; Smolinski, P.; et al. Subcutaneous infliximab (CT-P13) as maintenance therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: Two randomized phase 3 trials (LIBERTY). Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeire, S.; D’Haens, G.; Baert, F.; Danese, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Loftus, E.V.; Bhatia, S.; Agboton, C.; Rosario, M.; Chen, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous vedolizumab in patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease: Results from the VISIBLE2 randomised trial. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Baert, F.; Danese, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Kobayashi, T.; Yao, X.; Chen, J.; Rosario, M.; Bhatia, S.; Kisfalvi, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab subcutaneous formulation in a randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 562–572.e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberio, B.; Gracie, D.J.; Black, C.J.; Ford, A.C. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in induction and maintenance of remission in luminal Crohn’s disease: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2023, 72, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Murad, M.H.; Fumery, M.; Sedano, R.; Jairath, V.; Panaccione, R.; Sandborn, W.J.; Ma, C. Comparative efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasa, J.S.; Olivera, P.A.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecule drugs for patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Bossuyt, P.; Bettenworth, D.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Anjie, S.; D’Haens, G.; Saruta, M.; Arkkila, P.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, D.; et al. P445 Network meta-analysis to evaluate the comparative efficacy of intravenous and subcutaneous infliximab and vedolizumab in the maintenance treatment of adult patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, i574–i576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, T. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab and Vedolizumab Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=483599 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knezevic, A. Overlapping Confidence Intervals and Statistical Significance. Available online: https://cscu.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/ci.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Reinisch, W.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Kornbluth, A.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Lichtiger, S.; D’Haens, G.; Diamond, R.H.; Broussard, D.L.; et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, K.K.; Olsen, I.C.; Goll, G.L.; Lorentzen, M.; Bolstad, N.; Haavardsholm, E.A.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Mork, C.; Jahnsen, J.; Kvien, T.K.; et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): A 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2304–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K.K.; Goll, G.L.; Sexton, J.; Bolstad, N.; Olsen, I.C.; Asak, O.; Berset, I.P.; Blomgren, I.M.; Dvergsnes, K.; Florholmen, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease after switching from originator infliximab: Exploratory analyses from the NOR-SWITCH main and extension trials. BioDrugs 2020, 34, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.D.; Pesegova, M.; Alexeeva, O.; Osipenko, M.; Lahat, A.; Dorofeyev, A.; Fishman, S.; Levchenko, O.; Cheon, J.H.; Scribano, M.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of biosimilar CT-P13 compared with originator infliximab in patients with active Crohn’s disease: An international, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority study. Lancet 2019, 393, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.; Ben-Horin, S.; Leszczyszyn, J.; Dudkowiak, R.; Lahat, A.; Gawdis-Wojnarska, B.; Pukitis, A.; Horynski, M.; Farkas, K.; Kierkus, J.; et al. Randomized controlled trial: Subcutaneous vs. intravenous infliximab CT-P13 maintenance in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2340–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Rutgeerts, P.; Hanauer, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Sands, B.E.; Lukas, M.; Fedorak, R.N.; Lee, S.; Bressler, B.; et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, B.E.; Sandborn, W.J.; Van Assche, G.; Lukas, M.; Xu, J.; James, A.; Abhyankar, B.; Lasch, K. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease in patients naive to or who have failed tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutgeerts, P.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Reinisch, W.; Olson, A.; Johanns, J.; Travers, S.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2462–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, N.; Wong, E.C.L.; Marshall, J.K.; Colombel, J.F.; Dulai, P.S.; Reinisch, W. Comparative efficacy for infliximab vs. vedolizumab in biologic naive ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1588–1597.e1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagan, B.G.; Rutgeerts, P.; Sands, B.E.; Hanauer, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Van Assche, G.; Axler, J.; Kim, H.J.; Danese, S.; et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feagan, B.G.; Rubin, D.T.; Danese, S.; Vermeire, S.; Abhyankar, B.; Sankoh, S.; James, A.; Smyth, M. Efficacy of vedolizumab induction and maintenance therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, regardless of prior exposure to tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 229–239.e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, B.E.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Danese, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Toruner, M.; Jonaitis, L.; Abhyankar, B.; Chen, J.; Rogers, R.; et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, E.M.; Kimball, A.B. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide with salicylic acid, and combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in acne. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 63, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, Z.H.; Bogdanovski, D.A.; Barratt-Stopper, P.; Paglinco, S.R.; Antonioli, L.; Rolandelli, R.H. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis show unique cytokine profiles. Cureus 2017, 9, e1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Cominelli, F. Tumor necrosis factor’s pathway in Crohn’s disease: Potential for intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, B.E.; Dubinsky, M.C.; D’Haens, G.; Schreiber, S.; Danese, S.; Hanauer, S.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, J.; Colombel, J.F. Treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease with subcutaneous infliximab leads to an endoscopic response across all segments of the colon and terminal ileum: A post hoc analysis of the LIBERTY-CD study. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, i1782–i1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Heien, H.C.; Herrin, J.; Dulai, P.S.; Sangaralingham, L.; Shah, N.D.; Sandborn, W.J. Comparative risk of serious infections with tumor necrosis factor α antagonists vs. vedolizumab in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e74–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A.e. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (Updated February 2022). Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 10 October 2024).

| Outcome | Maintenance Treatment | Estimate (95% CI) | Heterogeneity, I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical remission (CDAI score ≤ 150) | IFX | 0.64 (0.60–0.68) | 16% |

| VDZ | 0.40 (0.35–0.46) | 65% | |

| Clinical response (CDAI-100) | IFX | 0.71 (0.67–0.75) | 25% |

| VDZ | 0.47 (0.43–0.51) | 32% | |

| Mucosal healing | IFX | 0.31 (0.26–0.36) | 22% |

| VDZ | – | – | |

| CS-free remission | IFX | 0.40 (0.34–0.47) | 55% |

| VDZ | 0.34 (0.27–0.41) | 58% | |

| Any AEs | IFX | 0.75 (0.66–0.84) | 91% |

| VDZ | 0.83 (0.77–0.89) | 90% | |

| Any SAEs | IFX | 0.12 (0.08–0.16) | 76% |

| VDZ | 0.18 (0.12–0.24) | 91% | |

| Any serious infection | IFX | 0.03 (0.02–0.05) | 0% |

| VDZ | 0.04 (0.02–0.06) | 74% | |

| Discontinuation due to AEs | IFX | 0.07 (0.01–0.13) | 90% |

| VDZ | 0.09 (0.06–0.12) | 79% |

| Outcome | Maintenance Treatment | Estimate (95% CI) | Heterogeneity, I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical remission (total/partial Mayo score) a | IFX | 0.54 (0.38–0.71) | 96% |

| VDZ | 0.40 (0.35–0.44) | 67% | |

| Clinical response (total/partial Mayo score) b | IFX | 0.52 (0.45–0.58) | 55% |

| VDZ | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) | 68% | |

| Mucosal healing | IFX | 0.48 (0.41–0.54) | 77% |

| VDZ | 0.48 (0.39–0.57) | 92% | |

| CS-free remission | IFX | 0.34 (0.27–0.40) | 0% |

| VDZ | 0.28 (0.19–0.38) | 88% | |

| Any AEs | IFX | 0.74 (0.64–0.83) | 91% |

| VDZ | 0.76 (0.69–0.83) | 92% | |

| Any SAEs | IFX | 0.12 (0.07–0.17) | 80% |

| VDZ | 0.11 (0.08–0.13) | 38% | |

| Any serious infection | IFX | 0.03 (0.02–0.04) | 22% |

| VDZ | 0.02 (0.01–0.02) | 0% | |

| Discontinuation due to AEs | IFX | 0.04 (0.02–0.06) | 61% |

| VDZ | 0.06 (0.03–0.09) | 62% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sands, B.E.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Schreiber, S.; Danese, S.; Armuzzi, A.; Buisson, A.; Fumery, M.; Dignass, A.; Powell, N.; Kennedy, N.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab and Vedolizumab Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134419

Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Schreiber S, Danese S, Armuzzi A, Buisson A, Fumery M, Dignass A, Powell N, Kennedy NA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab and Vedolizumab Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134419

Chicago/Turabian StyleSands, Bruce E., Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet, Stefan Schreiber, Silvio Danese, Alessandro Armuzzi, Anthony Buisson, Mathurin Fumery, Axel Dignass, Nick Powell, Nicholas A. Kennedy, and et al. 2025. "Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab and Vedolizumab Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134419

APA StyleSands, B. E., Peyrin-Biroulet, L., Schreiber, S., Danese, S., Armuzzi, A., Buisson, A., Fumery, M., Dignass, A., Powell, N., Kennedy, N. A., Zeissig, S., Kwon, T., Kim, S., Nam, K., & Hanauer, S. B. (2025). Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab and Vedolizumab Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134419