Multidisciplinary Care Model as a Center of Excellence for Fabry Disease: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Management by Clinical Specialty in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Genetic Medicine Diagnosis

|

Cardiology

|

Nephrology

|

| Neurology Patients with FD are at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and should follow a comprehensive stroke prevention strategy, especially in ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Recommendations for secondary prevention of stroke follow American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines. Management of risk factors for stroke

|

Gastroenterology

|

Otorhinolaryngology

|

Ophthalmology

|

Pain Management

|

2. Diagnosis and Follow-Up Assessments

2.1. Genetics

- Measure GLA enzyme activity in blood, with GLA activity < 1% being highly suggestive of classic FD.

- Genetic testing involves sequencing the GLA gene to confirm the diagnosis.

- Genetic testing by sequencing the GLA gene is mandatory.

- Measurement of GLA enzyme activity is optional, as the activity may be within the normal range due to random X-chromosome inactivation.

- Comprehensive medical history and physical examination.

- Family history assessment.

- Baseline organ function tests:

- ✓

- Renal function: proteinuria, microalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

- ✓

- Cardiac function: echocardiography, electrocardiography (ECG), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI)

- ✓

- Neurological assessment: Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nerve conduction studies

- ✓

- Ophthalmological examination

- ✓

- Audiology assessment

- Regular follow-up visits (frequency depends on disease severity and treatment status)

- Periodic organ function assessments:

- ✓

- Renal function: Every 6–12 months

- ✓

- Cardiac function: Annually or more frequently if indicated

- ✓

- Neurological assessment: Annually

- ✓

- Ophthalmological and audiology examinations: Annually

- Biomarker monitoring:

- ✓

- Lyso-Gb3 levels: To assess treatment response and disease progression

- ✓

- hsTNT of TNI: For cardiac involvement

- Genetic counseling:

- ✓

- Discuss inheritance pattern and implications for family members

- ✓

- Genetic testing should be offered to at-risk relatives

2.2. Cardiology

- ECG and Holter monitoring: A short PR interval due to increased atrioventricular (AV) conduction without evidence of an accessory pathway is the earliest ECG feature in the subclinical stage of FD cardiomyopathy [9]. Voltage signs of LVH, strain pattern, and T-wave inversion in the precordial leads are the usual findings when overt FD cardiomyopathy has developed. In progressed overt FD cardiomyopathy, sinus bradycardia and advanced conduction abnormalities in the AV node/His bundle and distal conduction system are common and suggest an adverse prognosis [10]. Therefore, serial ECG follow-up and side-by-side comparison of ECGs are necessary for assessing disease progression. According to a study by Shah et al. published in 2005, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), defined as three or more consecutive ventricular premature beats at a rate of ≥100 beats per minute lasting less than 30 s, was a common finding on Holter monitoring in patients with Fabry disease—observed in 38% of males and 39% of females aged 60 years or older [11]. The prevalence of malignant ventricular arrhythmias increases with age and is associated with the extent of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) [12]. Although, as in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the relationship between NSVT and the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) remains unclear, prophylactic strategies for SCD should be considered in cases of NSVT detected in Holter monitoring, accompanied by LGE [7].

- Echocardiography is the most useful tool for diagnosing and monitoring cardiac involvement of FD. The typical findings are left ventricular (LV), right ventricular (RV), or papillary muscle hypertrophy, sometimes mimicking diffuse-type hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. However, asymmetric thickening of the interventricular septum or apical hypertrophy cannot exclude FD cardiomyopathy [7]. Myocardial strain and strain rate are useful for detecting early changes in non-overt FD cardiomyopathies. In treatment naïve patients with FD, early reduction of LV longitudinal strain (particularly basal segments) can develop without clear-cut LVH [13]. Valves can also be involved, as well as the myocardium. The mitral and aortic valves are often thickened, with mild-to-moderate regurgitation, whereas stenotic lesions are rare. As myocardial fibrosis develops during disease progression, paradoxical thinning and hypokinetic or akinetic movement of the involved segments can be observed. These findings suggest that severe and irreversible changes are associated with poor prognosis. According to a study conducted in Taiwan, 38.1% of males and 16.7% of females with late-onset FD had cardiac fibrosis, even without LVH [14]. The echocardiographic parameters that must be assessed are LV mass/mass index, velocity of the septal mitral annulus in early diastole (septal e’), ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity (E/e’), maximal tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TR Vmax), right ventricular systolic excursion velocity (RV s’), tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP), global longitudinal strain (GLS), and isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT), in addition to routine parameters.

- CMRI provides an accurate assessment of LV size, mass, and geometry. The gadolinium contrast images visualize the localization and extent of myocardial fibrosis. The presence of extensive fibrosis is associated with a reduced response to ERT and an increased risk of arrhythmia [7]. CMRI can be used for differential diagnosis as well as for the prediction of prognosis. CMRI can also be used safely in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease and in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Native T1 mapping values (i.e., measured without contrast media such as gadolinium) are lower in patients with FD than in patients with normal myocardium, possibly due to sphingolipid accumulation [15].

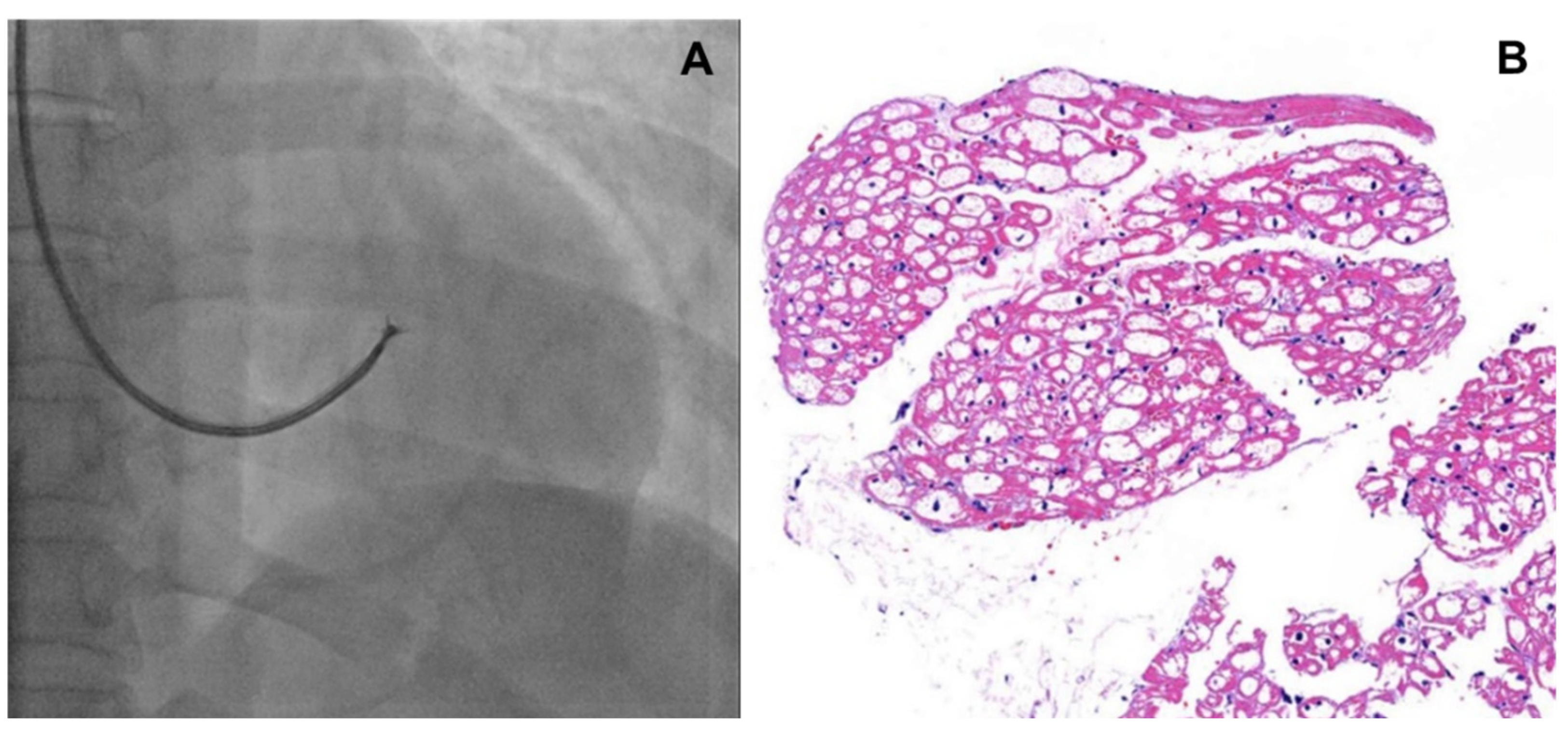

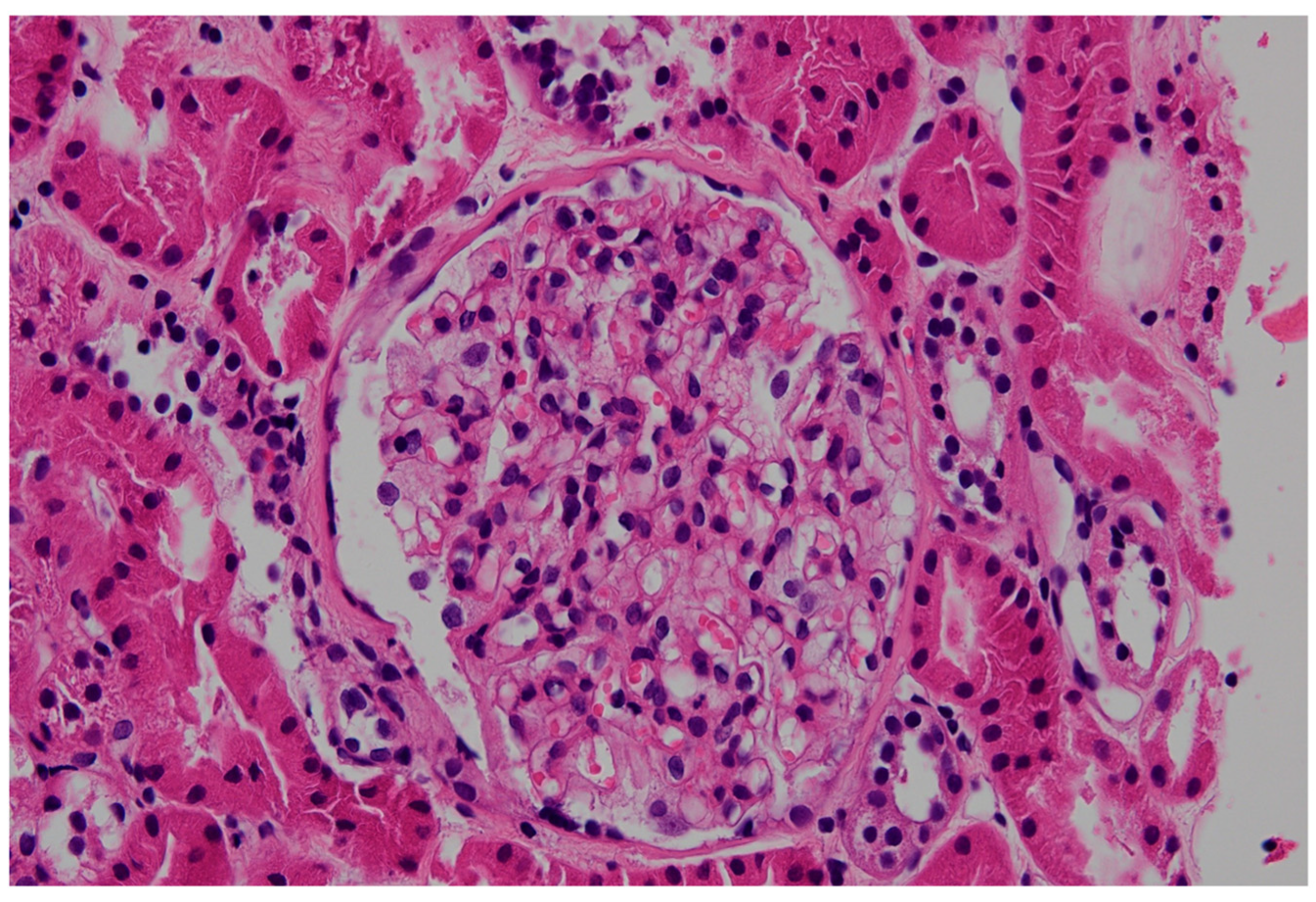

- Although endomyocardial biopsy (EMB, Figure 1) is not recommended to determine treatment efficacy or to follow up cardiac involvement, it can be considered as a confirmatory diagnostic tool in patients with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) or suspected cardiac variant of FD [7]. In addition, for patients who are not able to discontinue anticoagulation, EMB could be a good alternative for kidney biopsy. Lamellar bodies and intracellular inclusions found in electron microscopy provide strong evidence to diagnose FD.

- Coronary angiography: Damage to the coronary vascular bed by accumulation of glycolipids and secondary inflammations may lead to angina pectoris, variant angina, and myocardial infarction that do not necessarily follow the typical patterns observed in atherosclerosis [7]. Endothelial dysfunction with vasospasm and thrombotic events predominantly involves small, penetrating vessels. Therefore, angina symptoms in patients with FD need to be clarified by a coronary angiogram.

2.3. Nephrology

2.4. Neurology

- Ischemic stroke: Ischemic strokes are more common in patients with FD than in the general population, often occurring at a younger age [22]. Strokes in Fabry patients are often due to small vessel disease, but larger vessel involvement and cardioembolism can also occur due to atrial fibrillation (AF) or other cardiac abnormalities related to FD [23].

- Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs): TIAs are characterized by brief episodes of neurological dysfunction caused by temporary ischemia, lasting less than 24 h. TIAs are often a warning sign of a future stroke and require immediate medical attention and preventive treatment.

- Cerebral small vessel disease: The accumulation of Gb3 in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells of small blood vessels leads to their dysfunction and damage. This can result in thickening of the vessel walls, narrowing of the lumen, and reduced blood flow. These lesions are often detected incidentally on MRI scans such as white matter lesions and lacunar infarcts, even in asymptomatic patients [24]. They indicate chronic microvascular damage and are more prevalent in patients with FD. White matter lesions are associated with cognitive decline, memory impairment, and other neuropsychological deficits, contributing to the overall neurological burden in patients with FD.

- Cerebral large vessel disease: While small vessel disease is more common in FD, some patients may also present with large cerebral vessel involvement due to Gb3 accumulation. In some cases, these patients may develop stenosis, aneurysms, or dolichoectasia, or present with large vessel dissection, contributing to cerebrovascular events. Large vessel disease can lead to ischemic strokes from either atherosclerotic changes or emboli.

- Chronic neurologic symptoms: Patients may experience chronic headaches, dizziness, vertigo, and cognitive difficulties over time. Some patients may also present with silent strokes, which are small ischemic events that go unnoticed but can accumulate and lead to significant neurological impairment. Cognitive decline is common due to repeated ischemic events and the presence of white matter lesions. Patients may experience memory loss, difficulty concentrating, and other executive function deficits [25,26].

2.5. Gastroenterology

2.6. Otorhinolaryngology

- For adults: The initial otolaryngological hearing tests should include pure-tone audiometry (PTA), tympanometry, and Otoacoustic Emission (OAE) [39]. Depending on the patient’s reported symptoms, speech audiometry (SA) and tinnitogram (tinnitus pitch and loudness matching) can be added. PTA is the most widelyused subjective hearing test for assessinghearing thresholds across different frequencies. The OAE, particularly Distortion Product-OAE (DPOAE), is an objective hearing test that can detect early dysfunction of the outer hair cells in the cochlea. It can be used as a screening tool for patients with normal hearing who present with otological symptoms [41].

- For pediatric patients: PTA can be used reliably from 5 years of age onwards, under the guidance of a familiar audiologist. For younger children, visual reinforcement audiometry or play audiometry can be employed. However, these tests are subjective and may not always be accurate [42]. To overcome these limitations, objective hearing threshold measurements using DPOAE, Auditory Brain Response, and Auditory Steady State Response should be conducted.

- Adult patients: For adults with normal hearing, there are no established principles for periodic hearing tests. However, hearing thresholds tend to increase with age [43], and hearing tests are recommended for adults with risk factors such as a family history of FD, genetic disorders associated with hearing loss, or noise exposure [44]. We recommend that patients with FD undergo periodic hearing tests for the early detection of hearing loss, even in the absence of reported symptoms.

- Pediatric patients: According to the newborn screening guidelines in South Korea, it is recommended that infants at high-risk for hearing loss should undergo regular otolaryngological examinations every 6 months to 1 year until school age, even if they pass the newborn hearing screening. These examinations should include an assessment of language development, otoscopy, and detailed hearing tests [45]. In line with these recommendations, we recommend that pediatric patients with FD undergo age-appropriate hearing tests at least once a year.

- Symptomatic patients: For patients complaining of dizziness or vertigo, we recommend conducting vestibular function tests as needed. In cases of sudden onset of symptoms such as SSNHL or acute vertigo, prompt otolaryngological consultations and appropriate treatment should be provided.

2.7. Ophthalmology

2.8. Dermatology

2.9. Pathology

3. Diagnostic Challenges in Cases with a Variant of Uncertain Significance of the GLA Gene

- Heterogeneous clinical presentation: FD manifestations are highly variable, even among individuals with the same variant. This variability complicates the correlation between genotype and phenotype.

- Residual enzyme activity: Some VUS may result in partial enzyme activity, leading to milder or late-onset forms of the disease that are harder to diagnose.

- Lack of specific biomarkers: In some individuals with VUS, FD-specific biomarkers and imaging findings may not uncover evidence of organ involvement.

- Coexisting conditions: FD often coexists with other nephrotic disorders, such as IgA nephropathy, further complicating diagnosis [62].

4. FD Treatment and Management of Associated Symptoms and Risk Factors

4.1. Genetics: ERT or Chaperone Therapy

4.2. Cardiology and Neurology

4.2.1. Hypertension

4.2.2. Dyslipidemia

4.2.3. Coexisting Diabetes

4.2.4. Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

4.2.5. Antiplatelet Therapy

4.3. Nephrology

4.4. Gastroenterology

4.5. Otorhinolaryngology

4.6. Pain Management

5. Discussion

- Evidence supports the role of a multidisciplinary team approach in managing Fabry disease

- Our experiences of the MDT approach for FD diagnosis and management

5.1. Future Direction for Improved Diagnosis and Management of VUS Cases

5.2. Areas of Improvement in Reimbursement Criteria of FD Treatment in South Korea

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ASA | American Stroke Association |

| CEA | Carotid endarterectomy |

| CMRI | Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

| DPOAE | Distortion Product Otoacoustic Emission |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EMB | Endomyocardial biopsy |

| FD | Fabry disease |

| Gb3 | Globotriaosylceramide |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| GLA | Alpha-galactosidase A |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| HDL | High-density cholesterol |

| hsTNT | High-sensitive troponin T |

| LDL | Low density lipoprotein |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| LVH | Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary team |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| OAE | Otoacoustic Emission |

| PNUYH | Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital |

| PTA | Pure Tone Audiometry |

| RV | Right ventricular |

| SA | Speech Audiometry |

| TIA | Transient ischemic attack |

| VUS | Variants of uncertain significance |

References

- Schiffmann, R.; Fuller, M.; Clarke, L.A.; Aerts, J.M.F.G. Is it Fabry disease? Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeley, C.C.; Klionsky, B. Fabry’s disease: Classification as a sphingolipidosis and partial characterization of a novel glycolipid. J. Biol. Chem. 1963, 238, 3148–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torralba-Cabeza, M.A.; Olivera-Gonzalez, S.; Sierra-Monzon, J.L. The Importance of a Multidisciplinary Approach in the Management of a Patient with Type I Gaucher Disease. Diseases 2018, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macken, W.L.; Falabella, M.; McKittrick, C.; Pizzamiglio, C.; Ellmers, R.; Eggleton, K.; Woodward, C.E.; Patel, Y.; Labrum, R.; Genomics England Research Consortium; et al. Specialist multidisciplinary input maximises rare disease diagnoses from whole genome sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare of South Korea. Details on the Application Criteria and Methods of Nursing Care Benefits; Notice No. 2019-313, effective date: 2020.01.01; Ministry of Health and Welfare of South Korea: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Doheny, D.; Srinivasan, R.; Pagant, S.; Chen, B.; Yasuda, M.; Desnick, R.J. Fabry Disease: Prevalence of affected males and heterozygotes with pathogenic GLA mutations identified by screening renal, cardiac and stroke clinics, 1995–2017. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhart, A.; Germain, D.P.; Olivotto, I.; Akhtar, M.M.; Anastasakis, A.; Hughes, D.; Namdar, M.; Pieroni, M.; Hagege, A.; Cecchi, F.; et al. An expert consensus document on the management of cardiovascular manifestations of Fabry disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1076–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Kim, M.; Hong, G.R.; Kim, D.S.; Son, J.W.; Cho, I.J.; Shim, C.Y.; Chang, H.J.; Ha, J.W.; Chung, N. Fabry disease in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A practical approach to diagnosis. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 61, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, M.; Steffel, J.; Vidovic, M.; Brunckhorst, C.B.; Holzmeister, J.; Luscher, T.F.; Jenni, R.; Duru, F. Electrocardiographic changes in early recognition of Fabry disease. Heart 2011, 97, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, C.; Coats, C.; Cardona, M.; Garcia, A.; Calcagnino, M.; Murphy, E.; Lachmann, R.; Mehta, A.; Hughes, D.; Elliott, P.M. Incidence and predictors of anti-bradycardia pacing in patients with Anderson-Fabry disease. Europace 2011, 13, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.S.; Hughes, D.A.; Sachdev, B.; Tome, M.; Ward, D.; Lee, P.; Mehta, A.B.; Elliott, P.M. Prevalence and clinical significance of cardiac arrhythmia in Anderson-Fabry disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J.; Niemann, M.; Stork, S.; Frantz, S.; Beer, M.; Ertl, G.; Wanner, C.; Weidemann, F. Relation of burden of myocardial fibrosis to malignant ventricular arrhythmias and outcomes in Fabry disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, R.; Galderisi, M.; Santoro, C.; Imbriaco, M.; Riccio, E.; Maria Pellegrino, A.; Sorrentino, R.; Lembo, M.; Citro, R.; Angela Losi, M.; et al. Prominent longitudinal strain reduction of left ventricular basal segments in treatment-naïve Anderson-Fabry disease patients. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 20, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.R.; Hung, S.C.; Chang, F.P.; Yu, W.C.; Sung, S.H.; Hsu, C.L.; Dzhagalov, I.; Yang, C.F.; Chu, T.H.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Later Onset Fabry Disease, Cardiac Damage Progress in Silence: Experience with a Highly Prevalent Mutation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 2554–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sado, D.M.; White, S.K.; Piechnik, S.K.; Banypersad, S.M.; Treibel, T.; Captur, G.; Fontana, M.; Maestrini, V.; Flett, A.S.; Robson, M.D.; et al. Identification and assessment of Anderson-Fabry disease by cardiovascular magnetic resonance noncontrast myocardial T1 mapping. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, A.; Morel, C.F.; Eijgelsheim, M.; de Jong, M.F.C.; Broekroelofs, J.; Vogt, L.; Knoers, N.; de Borst, M.H. Fabry disease with atypical phenotype identified by massively parallel sequencing in early-onset kidney failure. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fervenza, F.C.; Torra, R.; Lager, D.J. Fabry disease: An underrecognized cause of proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, F.; Sanchez-Nino, M.D.; Politei, J.; Oliveira, J.P.; Wanner, C.; Warnock, D.G.; Ortiz, A. Fibrosis: A key feature of Fabry disease with potential therapeutic implications. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Cheon, C.K. Fabry nephropathy before and after enzyme replacement therapy: Important role of renal biopsy in patients with Fabry disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 40, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levstek, T.; Vujkovac, B.; Trebusak Podkrajsek, K. Biomarkers of Fabry Nephropathy: Review and Future Perspective. Genes 2020, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, M.S.; Park, S.; Cho, E.; Han, S.S.; Koh, E.S.; Chung, B.H.; Jeong, K.H.; Bae, E.; et al. A questionnaire survey on the diagnosis and treatment of Fabry nephropathy in clinical practice. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 42, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfs, A.; Fazekas, F.; Grittner, U.; Dichgans, M.; Martus, P.; Holzhausen, M.; Böttcher, T.; Heuschmann, P.U.; Tatlisumak, T.; Tanislav, C.; et al. Acute cerebrovascular disease in the young: The Stroke in Young Fabry Patients study. Stroke 2013, 44, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Chen, J.; Pongmoragot, J.; Lanthier, S.; Saposnik, G. Prevalence of Fabry disease in stroke patients--a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazekas, F.; Enzinger, C.; Schmidt, R.; Dichgans, M.; Gaertner, B.; Jungehulsing, G.J.; Hennerici, M.G.; Heuschmann, P.; Holzhausen, M.; Kaps, M.; et al. MRI in acute cerebral ischemia of the young: The Stroke in Young Fabry Patients (sifap1) Study. Neurology 2013, 81, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körver, S.; Geurtsen, G.J.; Hollak, C.E.M.; van Schaik, I.N.; Longo, M.G.F.; Lima, M.R.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.W.; Langeveld, M. Cognitive functioning and depressive symptoms in Fabry disease: A follow-up study. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsdottir, L.; Tchan, M.C.; Knopman, A.A.; Menzies, G.C.; Batchelor, J.; Sillence, D.O. Cognitive and psychological functioning in Fabry disease. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014, 29, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilz, M.J.; Arbustini, E.; Dagna, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Goizet, C.; Lacombe, D.; Liguori, R.; Manna, R.; Politei, J.; Spada, M.; et al. Non-specific gastrointestinal features: Could it be Fabry disease? Dig. Liver Dis. 2018, 50, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, P.B.; Baehner, A.F.; Barba Romero, M.A.; Hughes, D.A.; Kampmann, C.; Beck, M. Natural history of Fabry disease in females in the Fabry Outcome Survey. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 43, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, U.; Whybra, C.; Parini, R.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Mehta, A.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Widmer, U.; Beck, M. Clinical manifestations of Fabry disease in children: Data from the Fabry Outcome Survey. Acta Paediatr. 2006, 95, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, A.L.; Lamoureux, R.E.; Taylor, F.; Barth, J.A.; Mulberg, A.E.; Kessler, V.; Skuban, N. FABry Disease Patient-Reported Outcome-GastroIntestinal (FABPRO-GI): A new Fabry disease-specific gastrointestinal outcomes instrument. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2983–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugelmo, G.; Vitturi, N.; Francini-Pesenti, F.; Fasan, I.; Lenzini, L.; Valentini, R.; Carraro, G.; Avogaro, A.; Spinella, P. Gastrointestinal Manifestations and Low-FODMAP Protocol in a Cohort of Fabry Disease Adult Patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.F.; Xirasagar, S.; Chen, C.S.; Niu, D.M.; Lin, H.C. Association of Fabry Disease with Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Sudden Hearing Loss: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köping, M.; Shehata-Dieler, W.; Schneider, D.; Cebulla, M.; Oder, D.; Müntze, J.; Nordbeck, P.; Wanner, C.; Hagen, R.; Schraven, S.P. Characterization of vertigo and hearing loss in patients with Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P.; Fouilhoux, A.; Decramer, S.; Tardieu, M.; Pillet, P.; Fila, M.; Rivera, S.; Deschênes, G.; Lacombe, D. Consensus recommendations for diagnosis, management and treatment of Fabry disease in paediatric patients. Clin. Genet. 2019, 96, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.N.; Han, G.C.; Cho, Y.S.; Byun, J.Y.; Shin, J.E.; Chu, H.S.; Cheon, B.C.; Chung, J.W.; Chae, S.W.; Choi, J.Y. Standardization for a Korean Version of Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2011, 54, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Lim, S.L.; Shin, J.N.; Chung, W.H.; Yu, B.H.; Hong, S.H. Reliability and Validity of a Korean Adaptation of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2002, 45, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.C.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.; Lee, H.; Jeon, E.; Lee, H.; Cheon, B.C.; Kim, K.S.; Gon, E.; et al. The Study of Standardization for a Korean Adaptation of Self-report Measures of Dizziness. Res. Vestib. Sci. 2004, 3, 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-H.; Cha, H.E.; Lee, J.-G.; Im, G.J.; Song, J.-J.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, I.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Byun, J.Y.; Chae, S.-W. The Study of Standardization for a Korean Dizziness Handicap Inventory for Patient Caregivers. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2019, 62, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, C.M.; Germain, D.P.; Banikazemi, M.; Warnock, D.G.; Wanner, C.; Hopkin, R.J.; Bultas, J.; Lee, P.; Sims, K.; Brodie, S.E.; et al. Fabry disease: Guidelines for the evaluation and management of multi-organ system involvement. Genet. Med. 2006, 8, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeveld, M.; Hollak, C.E.; Klein van Loon, S.; van der Veen, S.; el Sayed, M.; Eskes, E. Protocol: Diagnosis, Evaluation and Treatment of Fabry Disease in the Netherlands; Amsterdam UMC: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Yamamoto, H.; Yoshida, T.; Sugimoto, S.; Teranishi, M.; Tsuboi, K.; Sone, M. Otological aspects of Fabry disease in patients with normal hearing. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2019, 81, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeldt, J.; Kolb, C.M. Hearing Loss Assessment in Children. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.H.; Shin, S.H.; Byun, S.W.; Kim, J.Y. Age- and Gender-Related Mean Hearing Threshold in a Highly-Screened Population: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2012. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Adult Hearing Screening (Practice Portal). Available online: www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Professional-Issues/Adult-Hearing-Screening/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Newborn Hearing Screening Special Committee of the Korean Audiological Society. Newborn Hearing Screening Guideline Update in Korea. 2018. Available online: https://hearingscreening.or.kr/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Gambini, G.; Scartozzi, L.; Giannuzzi, F.; Carlà, M.M.; Boselli, F.; Caporossi, T.; De Vico, U.; Baldascino, A.; Rizzo, S. Ophthalmic Manifestations in Fabry Disease: Updated Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Choi, B.S.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.S. In Vivo Confocal Microscopic Findings of Corneal Tissue in Amiodarone-Induced Vortex Keratopathy. J. Korean Ophthalmol. Soc. 2015, 56, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthagani, J.; MacDonald, T.; Bruynseels, A.; Madathilethu, S.C.; Jenyon, T. Deposition keratopathy. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 83, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkum, G.; Pitz, S.; Karabul, N.; Beck, M.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Parini, R.; Rohrbach, M.; Bizjajeva, S.; Ramaswami, U. Paediatric Fabry disease: Prognostic significance of ocular changes for disease severity. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orteu, C.H.; Jansen, T.; Lidove, O.; Jaussaud, R.; Hughes, D.A.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Ramaswami, U.; Parini, R.; Sunder-Plassman, G.; Beck, M.; et al. Fabry disease and the skin: Data from FOS, the Fabry outcome survey. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 157, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermot, K.D.; Holmes, A.; Miners, A.H. Anderson-Fabry disease: Clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 60 obligate carrier females. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 38, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W. A case of “angio-keratoma”. Br. J. Dermatol. 1898, 10, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W.R.; Oliveira, J.P.; Hopkin, R.J.; Ortiz, A.; Banikazemi, M.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Sims, K.; Waldek, S.; Pastores, G.M.; Lee, P.; et al. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: Lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008, 93, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilz, M.J.; Brys, M.; Marthol, H.; Stemper, B.; Dütsch, M. Enzyme replacement therapy improves function of C-, Adelta-, and Abeta-nerve fibers in Fabry neuropathy. Neurology 2004, 62, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidove, O.; Ramaswami, U.; Jaussaud, R.; Barbey, F.; Maisonobe, T.; Caillaud, C.; Beck, M.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Linhart, A.; Mehta, A. Hyperhidrosis: A new and often early symptom in Fabry disease. International experience and data from the Fabry Outcome Survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.G.; Moore, M.J.; Lager, D.J. Fabry disease: A morphologic study of 11 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.A.B.; Moura-Neto, J.A.; Dos Reis, M.A.; Vieira Neto, O.M.; Barreto, F.C. Renal Manifestations of Fabry Disease: A Narrative Review. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2021, 8, 2054358120985627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gragnaniello, V.; Burlina, A.P.; Commone, A.; Gueraldi, D.; Puma, A.; Porcù, E.; Stornaiuolo, M.; Cazzorla, C.; Burlina, A.B. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease: Current Status of Knowledge. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2023, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P.; Levade, T.; Hachulla, E.; Knebelmann, B.; Lacombe, D.; Seguin, V.L.; Nguyen, K.; Noël, E.; Rabès, J.P. Challenging the traditional approach for interpreting genetic variants: Lessons from Fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 2022, 101, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Tol, L.; Smid, B.E.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Biegstraaten, M.; Deprez, R.H.; Linthorst, G.E.; Hollak, C.E. A systematic review on screening for Fabry disease: Prevalence of individuals with genetic variants of unknown significance. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, I.; Souto-Rodriguez, O.; Fernandez-Mosquera, L.; San Millan, B.; Teijeira, S.; Fernandez-Martin, J.; Martinez-Sanchez, F.; Aldamiz-Echevarria, L.J.; Lopez-Rodriguez, M.; Navarro, C.; et al. Fabry disease in the Spanish population: Observational study with detection of 77 patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Caputo, C.; Repetto, M.; Somaschini, A.; Pietro, B.; Colomba, P.; Zizzo, C.; Parodi, A.; Zanetti, V.; Canepa, M.; et al. Diagnosing Fabry nephropathy: The challenge of multiple kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlina, A.; Brand, E.; Hughes, D.; Kantola, I.; Krämer, J.; Nowak, A.; Tøndel, C.; Wanner, C.; Spada, M. An expert consensus on the recommendations for the use of biomarkers in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, S.J.; Hollak, C.E.M.; van Kuilenburg, A.B.P.; Langeveld, M. Developments in the treatment of Fabry disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 908–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.; Kalra, D.K. Treatment of Fabry Disease: Established and Emerging Therapies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, M.; Biegstraaten, M.; Wanner, C.; Sirrs, S.; Mehta, A.; Elliott, P.M.; Oder, D.; Watkinson, O.T.; Bichet, D.G.; Khan, A.; et al. Agalsidase alfa versus agalsidase beta for the treatment of Fabry disease: An international cohort study. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banikazemi, M.; Bultas, J.; Waldek, S.; Wilcox, W.R.; Whitley, C.B.; McDonald, M.; Finkel, R.; Packman, S.; Bichet, D.-G.; Warnock, D.G.; et al. Agalsidase-Beta Therapy for Advanced Fabry Disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampmann, C.; Perrin, A.; Beck, M. Effectiveness of agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement in Fabry disease: Cardiac outcomes after 10 years’ treatment. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhiqing, Z. Effectiveness and safety of enzyme replacement therapy in the treatment of Fabry disease: A Chinese monocentric real-world study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann, R.; Pastores, G.M.; Lien, Y.H.; Castaneda, V.; Chang, P.; Martin, R.; Wijatyk, A. Agalsidase alfa in pediatric patients with Fabry disease: A 6.5-year open-label follow-up study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Biagini, E.; Cianci, V.; Pieruzzi, F.; Pisani, A.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Pieroni, M. Effects of Current Therapies on Disease Progression in Fabry Disease: A Narrative Review for Better Patient Management in Clinical Practice. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 597–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, D.P.; Charrow, J.; Desnick, R.J.; Guffon, N.; Kempf, J.; Lachmann, R.H.; Lemay, R.; Linthorst, G.E.; Packman, S.; Scott, C.R.; et al. Ten-year outcome of enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase beta in patients with Fabry disease. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 52, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbey, F.; Livio, F. Safety of enzyme replacement therapy. In Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS; Mehta, A., Beck, M., Sunder-Plassmann, G., Eds.; Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswami, U.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Kampmann, C.; Nicholls, K.; Niu, D.M.; Reisin, R.; West, M.L.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Botha, J.; Jazukeviciene, D.; et al. Two decades of experience of the Fabry Outcome Survey provides further confirmation of the long-term effectiveness of agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement therapy. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2025, 43, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudit, G.Y.; DasMahapatra, P.; Lyn, N.; Wilson, F.R.; Adeyemi, A.; Lee, C.S.; Crespo, A.; Namdar, M. A systematic literature review to evaluate the cardiac and cerebrovascular outcomes of patients with Fabry disease treated with agalsidase Beta. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1415547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.L.; Hariri, A.; Maski, M.; Richards, S.; Gudivada, B.; Raynor, L.A.; Ponce, E.; Wanner, C.; Desnick, R.J. Reduction in kidney function decline and risk of severe clinical events in agalsidase beta-treated Fabry disease patients: A matched analysis from the Fabry Registry. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.A.; Nicholls, K.; Shankar, S.P.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Koeller, D.; Nedd, K.; Vockley, G.; Hamazaki, T.; Lachmann, R.; Ohashi, T.; et al. Oral pharmacological chaperone migalastat compared with enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: 18-month results from the randomised phase III ATTRACT study. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Hughes, D.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Shankar, S.; Nedd, K.; Olivotto, I.; Ortiz, D.; Ohashi, T.; Hamazaki, T.; Skuban, N.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of migalastat treatment in Fabry disease: 30-month results from the open-label extension of the randomized, phase 3 ATTRACT study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2020, 131, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P.; Hughes, D.A.; Nicholls, K.; Bichet, D.G.; Giugliani, R.; Wilcox, W.R.; Feliciani, C.; Shankar, S.P.; Ezgu, F.; Amartino, H.; et al. Treatment of Fabry’s Disease with the Pharmacologic Chaperone Migalastat. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichet, D.G.; Hopkin, R.J.; Aguiar, P.; Allam, S.R.; Chien, Y.H.; Giugliani, R.; Kallish, S.; Kineen, S.; Lidove, O.; Niu, D.M.; et al. Consensus recommendations for the treatment and management of patients with Fabry disease on migalastat: A modified Delphi study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1220637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Germain, D.P.; Desnick, R.J.; Politei, J.; Mauer, M.; Burlina, A.; Eng, C.; Hopkin, R.J.; Laney, D.; Linhart, A.; et al. Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 123, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunstrom, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, e364–e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.S.; Kang, S.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, K.A.; Moon, J.H.; Chon, S.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, H.J.; Seo, J.A.; Kim, M.K.; et al. 2023 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diabetes Management in Korea: Full Version Recommendation of the Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 546–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K.; Ko, S.B.; Jung, K.H.; Jang, M.U.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J.T.; Choi, J.C.; Jeong, H.S.; Kim, C.; Heo, J.H.; et al. 2022 Update of the Korean Clinical Practice Guidelines for Stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy for Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. J. Stroke 2022, 24, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Linhart, A.; Gurevich, A.; Kalampoki, V.; Jazukeviciene, D.; Feriozzi, S. Prompt Agalsidase Alfa Therapy Initiation is Associated with Improved Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in a Fabry Outcome Survey Analysis. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 3561–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimohata, H.; Yamashita, M.; Yamada, K.; Hirayama, K.; Kobayashi, M. Treatment of Fabry Nephropathy: A Literature Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argoff, C.E.; Barton, N.W.; Brady, R.O.; Ziessman, H.A. Gastrointestinal symptoms and delayed gastric emptying in Fabry’s disease: Response to metoclopramide. Nucl. Med. Commun. 1998, 19, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar-Kessler, C.; Karaa, A.; Sims, K.B.; Clarke, V.; Kuo, B. Understanding the gastrointestinal manifestations of Fabry disease: Promoting prompt diagnosis. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2016, 9, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ries, M.; Mengel, E.; Kutschke, G.; Kim, K.S.; Birklein, F.; Krummenauer, F.; Beck, M. Use of gabapentin to reduce chronic neuropathic pain in Fabry disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2003, 26, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, C.A. Tinnitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanfard, P.D.W.; Effraimidis, G.; Madsen, C.V.; Nielsen, L.H.; Rasmussen, Å.K.; Petersen, J.H.; Sørensen, S.S.; Køber, L.; Fraga de Abreu, V.H.; Larsen, V.A.; et al. Hearing loss in fabry disease: A 16 year follow-up study of the Danish nationwide cohort. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2022, 31, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, S.S.; Tsai Do, B.S.; Schwartz, S.R.; Bontempo, L.J.; Faucett, E.A.; Finestone, S.A.; Hollingsworth, D.B.; Kelley, D.M.; Kmucha, S.T.; Moonis, G.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Sudden Hearing Loss (Update). Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 161, S1–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, D.P. Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, Y.; Linthorst, G.E.; Hollak, C.E.; Van Schaik, I.N.; Biegstraaten, M. Pain management strategies for neuropathic pain in Fabry disease--a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chincholkar, M. Analgesic mechanisms of gabapentinoids and effects in experimental pain models: A narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 1315–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, H. Analgesic Mechanisms of Antidepressants for Neuropathic Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politei, J.M.; Bouhassira, D.; Germain, D.P.; Goizet, C.; Guerrero-Sola, A.; Hilz, M.J.; Hutton, E.J.; Karaa, A.; Liguori, R.; Üçeyler, N.; et al. Pain in Fabry Disease: Practical Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016, 22, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremont-Lukats, I.W.; Megeff, C.; Backonja, M.M. Anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain syndromes: Mechanisms of action and place in therapy. Drugs 2000, 60, 1029–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vučković, S.; Srebro, D.; Vujović, K.S.; Vučetić, Č.; Prostran, M. Cannabinoids and Pain: New Insights From Old Molecules. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.B.; Dworkin, R.H. Treatment of neuropathic pain: An overview of recent guidelines. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, S22–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogawski, M.A.; Löscher, W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of nonepileptic conditions. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.S.; Gottrup, H.; Sindrup, S.H.; Bach, F.W. The clinical picture of neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 429, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockman, L.A.; Hunninghake, D.B.; Krivit, W.; Desnick, R.J. Relief of pain of Fabry’s disease by diphenylhydantoin. Neurology 1973, 23, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, R.H.; O’Connor, A.B.; Backonja, M.; Farrar, J.T.; Finnerup, N.B.; Jensen, T.S.; Kalso, E.A.; Loeser, J.D.; Miaskowski, C.; Nurmikko, T.J.; et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence-based recommendations. Pain 2007, 132, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesters, M.; Martini, C.; Dahan, A. Ketamine for chronic pain: Risks and benefits. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 77, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasell, R.W.; Arnold, J.M. Alpha-1 adrenoceptor hyperresponsiveness in three neuropathic pain states: Complex regional pain syndrome 1, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain and central pain states following spinal cord injury. Pain Res. Manag. 2004, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paim-Marques, L.; de Oliveira, R.J.; Appenzeller, S. Multidisciplinary Management of Fabry Disease: Current Perspectives. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, P.; Hernan, A.; Beatriz, S.A.; Gustavo, C.; Antonio, M.; Eduardo, T.; Raul, D.; Margarita, L.; Mariana, B.; Daniela, G.; et al. Fabry disease: Multidisciplinary evaluation after 10 years of treatment with agalsidase Beta. JIMD Rep. 2014, 16, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, B.; Liu, F.; et al. Multidisciplinary approach to screening and management of children with Fabry disease: Practice at a Tertiary Children’s Hospital in China. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano, J.; Serra, V.; Pérez de Isla, L.; Feltes, G.; Calli, A.; Barbado, F.J.; Torras, J.; Hernandez, S.; Herrera, J.; Herrero, J.A.; et al. Usefulness of tissue Doppler on early detection of cardiac disease in Fabry patients and potential role of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) for avoiding progression of disease. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2011, 12, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frustaci, A.; Verardo, R.; Galea, N.; Alfarano, M.; Magnocavallo, M.; Marchitelli, L.; Sansone, L.; Belli, M.; Cristina, M.; Frustaci, E.; et al. Long-Term Clinical-Pathologic Results of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Prehypertrophic Fabry Disease Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, S.J.; Korver, S.; Hirsch, A.; Hollak, C.E.M.; Wijburg, F.A.; Brands, M.M.; Tondel, C.; van Kuilenburg, A.B.P.; Langeveld, M. Early start of enzyme replacement therapy in pediatric male patients with classical Fabry disease is associated with attenuated disease progression. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 135, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Eligibility criteria for ERT reimbursement of patients with FD | ||

Patients must meet both of the following criteria:

| ||

| Category | Requirements | |

| Nephrology * | 1. Decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (15 ≤ eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2; adjusted for age > 40 years) detected twice or more | |

| Male | 2. Microalbuminuria (>30 mg/g) (detected twice or more over a minimum interval of 24 h) | |

| 3. Albuminuria (>20 μg/min) (detected twice or more over a minimum interval of 24 h) | ||

| 4. Proteinuria (>150 mg/24 h) | ||

| Female | 5. Proteinuria with clinical evidence of progression (>300 mg/24 h) | |

| Cardiology | 6. Left ventricular hypertrophy (left ventricular wall thickness > 12 mm) diagnosed with magnetic resonance imaging or echocardiography (however, in patients with hypertension, at least 6 months of blood pressure treatment should be performed prior to administration of this drug), etc. | |

| 7. Clinically significant arrhythmias and conduction disturbances, etc. | ||

| Neurology | 8. Stroke or TIA confirmed by objective examination, etc. | |

| Pain | 9. Chronic, uncontrolled neuropathic pain despite the use of antiepileptic drugs and/or maximum dose analgesics (NSAIDs, etc.) (the drug effect must be continuously proven through medical records, etc., for continuous administration) | |

| Assessment of ERT effectiveness | ||

| Before initiating ERT, patients should undergo a comprehensive baseline evaluation. The therapeutic efficacy of ERT should be assessed periodically through renal function tests (e.g., eGFR) or cardiac function tests (e.g., ECG) at intervals of 6 to 12 months to monitor treatment response and disease progression. | ||

| Cardiac Examination | Classical | Non-Classical (Cardiac Variant) |

|---|---|---|

| B-type natriuretic peptide, ST2 | At initial assessment Every 6–12 months | At initial assessment Every 6–12 months |

| Lipid profiles | At initial assessment Every 6–12 months | At initial assessment Every 6–12 months |

| Electrocardiogram | At initial assessment Every 6–12 months | At initial assessment Every 6–12 months |

| 24 h Holter | At initial assessment Depending on symptoms | At initial assessment Depending on symptoms |

| Treadmill test | At initial assessment Every 12 months | At initial assessment Every 12 months |

| Echocardiography | At initial assessment Every 12 months | At initial assessment Every 12 months |

| Exercise echocardiography | Depending on symptoms | Depending on symptoms |

| CMRI (including T1 mapping, late gadolinium enhancement) | At initial assessment Every 3–5 years | At initial assessment Every 3–5 years |

| Coronary angiography | Depending on symptoms (angina) | Depending on symptoms (angina) |

| Otorhinolaryngological Examination | Diagnosis and Follow-Up |

|---|---|

| PTA, SA | At initial assessment (for patients > 6 years old) Follow-up every 12 months |

| DPOAE | At initial assessment Follow-up every 12 months |

| Tympanometry | At initial assessment Follow-up every 12 months |

| Tinnitogram | Depending on symptoms |

| ABR, ASSR | At initial assessment (for patients < 6 years old, if DPOAE result was abnormal; and for patients > 6 years old, if they show signs of auditory neuropathy) Follow-up every 12 months (if earlier ABR or ASSR was abnormal) |

| Cranial nerve examination, Nystagmus test, Positional and positioning tests, Video head impulse test | Depending on symptoms |

| Agents | Mechanism of Action | Dose | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| First line | |||

Tricyclic antidepressants

| Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. Action on dopaminergic pathways and locus coeruleus. | 12.5–150 mg/day | Dry mouth, sedation, arrythmias, urinary retention, diarrhea, cognitive disturbance, worsening of autonomic instability |

| Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition | Serotonergic syndrome, gastrointestinal discomfort, diarrhea, anxiety, dizziness | |

|

| ||

|

| ||

| Carbamazepine | Reduced sodium channel conductance. Reduction in ectopic discharges. | 250–800 mg/bid | Associated with blood dyscrasias, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, hyponatremia |

| Phenytoin | 300 mg/day | ||

| Gabapentinoids | Inhibit calcium-mediated neurotransmitter release through effects on α2δ-1 subunits. NMDA receptor antagonism. | Weight gain, cognitive dysfunction, lethargy | |

|

| ||

|

| ||

| Second line | |||

| Intravenous lidocaine | Local anesthetic causing sodium channel blockade. | 2–5 mg/kg | Local anesthetic systemic toxicity |

| Topical capsaicin (8%) patches | Depletion of substance P | 0.0125% applied topically for 12 h daily | Burning, pruritus |

| Tramadol | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. μ-opioid receptor agonist. | 100–400 mg/day | May lower seizure threshold |

| Third line | |||

| Strong opioids | Opioid receptor agonists. | Nausea, constipation, itching, respiratory depression, osteoporosis, reduced immunity, endocrine dysfunction | |

|

| ||

|

| ||

| Fourth line | |||

| Methadone | NMDA antagonist activity Norepinephrine reuptake inhibition and μ-opioid receptor agonist. | 50 mg bid maximum 500 mg/day | Nausea, constipation, itching, respiratory depression, osteoporosis, reduced immunity, endocrine dysfunction |

| Tapentadol | Sodium channel blockade and suppressed release of glutamate. | 25 mg/day for 2 weeks up to a maximum of 400 mg/day. | Anxiety, anorexia asthenia, diarrhea, heat or cold intolerance, gastrointestinal discomfort, muscle spasms, sleep disorders, tremor |

| Less efficacious anti-convulsants (Lamotrigine, lacosamide) | Aggression, agitation, arthralgia, diarrhea, dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, fatigue, headache, irritability, nausea, pain, rash, sleep disorders, tremors, vomiting | ||

| Country | Summary of Reimbursement Criteria for ERT | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| South Korea |

|

|

| Australia |

|

|

| Europe (Italia and UK) |

|

|

| Japan |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.Y.; Kim, I.Y.; Ahn, S.-H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.-M.; Lee, J.E.; Byeon, G.-J.; Ko, H.-C.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, S.; et al. Multidisciplinary Care Model as a Center of Excellence for Fabry Disease: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Management by Clinical Specialty in South Korea. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134400

Lee SY, Kim IY, Ahn S-H, Kim SJ, Lee H-M, Lee JE, Byeon G-J, Ko H-C, Lee HJ, Choi S, et al. Multidisciplinary Care Model as a Center of Excellence for Fabry Disease: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Management by Clinical Specialty in South Korea. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134400

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Soo Yong, Il Young Kim, Sung-Ho Ahn, Su Jin Kim, Hyun-Min Lee, Ji Eun Lee, Gyeong-Jo Byeon, Hyun-Chang Ko, Hyun Jung Lee, Songhwa Choi, and et al. 2025. "Multidisciplinary Care Model as a Center of Excellence for Fabry Disease: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Management by Clinical Specialty in South Korea" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134400

APA StyleLee, S. Y., Kim, I. Y., Ahn, S.-H., Kim, S. J., Lee, H.-M., Lee, J. E., Byeon, G.-J., Ko, H.-C., Lee, H. J., Choi, S., & Cheon, C. K. (2025). Multidisciplinary Care Model as a Center of Excellence for Fabry Disease: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Management by Clinical Specialty in South Korea. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134400