Fear of Falling in Older Adults Undergoing Comprehensive Geriatric Care: Results of a Prospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Subjects, and Setting

2.2. Comprehensive Geriatric Care

2.3. Outcome Measures After Comprehensive Geriatric Care

2.3.1. Barthel Index

2.3.2. Tinetti Balance and Gait Test

2.3.3. Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)

2.3.4. Assessment of Fear of Falling (FOF)

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Ahmadipanah, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global Prevalence of Falls in the Older Adults: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hou, L.; Zhao, H.; Xie, R.; Yi, Y.; Ding, X. Risk Factors for Falls among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2023, 9, 1019094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Chang, S. Frailty as a Risk Factor for Falls Among Community Dwelling People: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-C.; Lin, H.; Jiang, G.-H.; Chu, Y.-H.; Gao, J.-H.; Tong, Z.-J.; Wang, Z.-H. Frailty Is a Risk Factor for Falls in the Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2023, 27, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittrakul, J.; Siviroj, P.; Sungkarat, S.; Sapbamrer, R. Physical Frailty and Fall Risk in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Aging Res. 2020, 2020, 3964973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hou, T.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Szanton, S.L.; Clemson, L.; Davidson, P.M. Fear of Falling Is as Important as Multiple Previous Falls in Terms of Limiting Daily Activities: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Delbaere, K.; Fitzgerald, T.D. Reconceptualizing the Role of Fear of Falling and Balance Confidence in Fall Risk. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, M.R.; Nilsson, M.H. A Theoretical Framework for Addressing Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior in Parkinson’s Disease. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2023, 39, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Wang, D.; Ren, W.; Liu, X.; Wen, R.; Luo, Y. The Global Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Fear of Falling among Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, E.; Hong, G.-R.S. Comparison of Factors Associated with Fear of Falling between Older Adults with and without a Fall History. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, S.; Ebert, P.; Harbidge, C.; Hogan, D.B. Fear of Falling in Older Adults: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature. Can. Geriatr. J. 2021, 24, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrie, M.; Saini, G.; Angeles, R.; Marzanek, F.; Parascandalo, J.; Agarwal, G. Risk of Falls and Fear of Falling in Older Adults Residing in Public Housing in Ontario, Canada: Findings from a Multisite Observational Study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oppen, J.D.; Conroy, S.P.; Coats, T.J.; Mackintosh, N.J.; Valderas, J.M. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life of Older People with Frailty Receiving Acute Care: Feasibility and Psychometric Performance of the EuroQol EQ-5D. BMC Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Swain, S.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Metsemakers, J.F.M.; van den Akker, M. Health Related Quality of Life in Multimorbidity: A Primary-Care Based Study from Odisha, India. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canever, J.B.; de Souza Moreira, B.; Danielewicz, A.L.; de Avelar, N.C.P. Are Multimorbidity Patterns Associated with Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults? BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esbrí-Víctor, M.; Huedo-Rodenas, I.; López-Utiel, M.; Navarro-López, J.L.; Martínez-Reig, M.; Serra-Rexach, J.A.; Romero-Rizos, L.; Abizanda, P. Frailty and Fear of Falling: The FISTAC Study. J. Frailty Aging 2017, 6, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, K.; Lee, S.; Bae, S.; Chiba, I.; Harada, K.; Katayama, O.; Shinkai, Y.; Makizako, H.; Shimada, H. Prospective Associations of Physical Frailty with Future Falls and Fear of Falling: A 48-Month Cohort Study. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L.F.; Canever, J.B.; de Souza Moreira, B.; Danielewicz, A.L.; de Avelar, N.C.P. Association Between Fear of Falling and Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Schmetsdorf, S.; Stein, T.; Niemoeller, U.; Arnold, A.; Reuter, I.; Kostev, K.; Grünther, R.-A.; Tanislav, C. Improved Balance and Gait Ability and Basic Activities of Daily Living after Comprehensive Geriatric Care in Frail Older Patients with Fractures. Healthcare 2021, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemöller, U.; Arnold, A.; Stein, T.; Juenemann, M.; Erkapic, D.; Rosenbauer, J.; Kostev, K.; Meyer, M.; Tanislav, C. Comprehensive Geriatric Care in Older Adults: Walking Ability after an Acute Fracture. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Arnold, A.; Stein, T.; Niemöller, U.; Tanislav, C.; Erkapic, D. Arrhythmias among Older Adults Receiving Comprehensive Geriatric Care: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E. Performance-oriented Assessment of Mobility Problems in Elderly Patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1986, 34, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köpke, S.; Meyer, G. The Tinetti Test: Babylon in Geriatric Assessment. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 39, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, K.I.; Shedletsky, R.; Silver, I.L. The Challenge of Time: Clock-Drawing and Cognitive Function in the Elderly. Int. J. Gen. Psychiatry 1986, 1, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, K.I.; Pushkar Gold, D.; Cohen, C.A.; Zucchero, C.A. Clock-Drawing and Dementia in the Community: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 1993, 8, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent Evidence and Development of a Shorter Version. Clin. Gerontol. 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and Validation of a Geriatric Depression Screening Scale: A Preliminary Report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübke, N.; Meinck, M.; Von Renteln-Kruse, W. The Barthel Index in Geriatrics. A Context Analysis of the Hamburg Classification Manual. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2004, 37, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Smith, H. A Prospective Study of the Relationship between Feared Consequences of Falling and Avoidance of Activity in Community-Living Older People. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardley, L.; Beyer, N.; Hauer, K.; Kempen, G.; Piot-Ziegler, C.; Todd, C. Development and Initial Validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005, 34, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Todd, C.J.; Beyer, N.; Freiberger, E.; Piot-Ziegler, C.; Yardley, L.; Hauer, K. The German Version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I). Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 39, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbaere, K.; Close, J.C.T.; Mikolaizak, A.S.; Sachdev, P.S.; Brodaty, H.; Lord, S.R. The Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I). A Comprehensive Longitudinal Validation Study. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, F.; Basile, C.; Liguori, I.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Galizia, G.; Testa, G.; Langellotto, A.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; et al. Tinetti Mobility Test Is Related to Muscle Mass and Strength in Non-Institutionalized Elderly People. Age 2016, 38, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletic, B.; Plisic, A.; Jelovica, L.; Saner, J.; Hesse, M.; Segulja, S.; Courteney, U.; Starcevic-Klasan, G. Depression and Its Effect on Geriatric Rehabilitation Outcomes in Switzerland’s Aging Population. Medicina 2025, 61, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemöller, U.; Arnold, A.; Stein, T.; Juenemann, M.; Farzat, M.; Erkapic, D.; Rosenbauer, J.; Kostev, K.; Meyer, M.; Tanislav, C. Comprehensive Geriatric Care in Older Hospitalized Patients with Depressive Symptoms. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschedijk, J.H.M.; Caljouw, M.A.A.; Bakkers, E.; van Balen, R.; Achterberg, W.P. Longitudinal Follow-up Study on Fear of Falling during and after Rehabilitation in Skilled Nursing Facilities. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roza, J.G.; Ng, D.W.L.; Mathew, B.K.; Jose, T.; Goh, L.J.; Wang, C.; Soh, C.S.C.; Goh, K.C. Factors Influencing Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Singapore: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Ory, M.G.; Won, J.; Towne, S.D.; Wang, S.; Forjuoh, S.N. Fear of Outdoor Falling Among Community-Dwelling Middle-Aged and Older Adults: The Role of Neighborhood Environments. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenouvel, E.; Novak, L.; Biedermann, A.; Kressig, R.W.; Klöppel, S. Preventive Treatment Options for Fear of Falling within the Swiss Healthcare System: A Position Paper. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 55, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.-W.; Ng, G.Y.F.; Chung, R.C.K.; Ng, S.S.M. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Fear of Falling and Balance among Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenouvel, E.; Ullrich, P.; Siemens, W.; Dallmeier, D.; Denkinger, M.; Kienle, G.; Zijlstra, G.A.R.; Hauer, K.; Klöppel, S. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) with and without Exercise to Reduce Fear of Falling in Older People Living in the Community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 11, CD014666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Delbaere, K.; Zijlstra, G.A.R.; Carpenter, H.; Iliffe, S.; Masud, T.; Skelton, D.; Morris, R.; Kendrick, D. Exercise for Reducing Fear of Falling in Older People Living in the Community: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K.; Kampe, K.; Klenk, J.; Rapp, K.; Kohler, M.; Albrecht, D.; Büchele, G.; Hautzinger, M.; Taraldsen, K.; Becker, C. Effects of an Intervention to Reduce Fear of Falling and Increase Physical Activity during Hip and Pelvic Fracture Rehabilitation. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampe, K.; Kohler, M.; Albrecht, D.; Becker, C.; Hautzinger, M.; Lindemann, U.; Pfeiffer, K. Hip and Pelvic Fracture Patients with Fear of Falling: Development and Description of the “Step by Step” Treatment Protocol. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkinger, M.D.; Igl, W.; Lukas, A.; Bader, A.; Bailer, S.; Franke, S.; Denkinger, C.M.; Nikolaus, T.; Jamour, M. Relationship between Fear of Falling and Outcomes of an Inpatient Geriatric Rehabilitation Population—Fear of the Fear of Falling. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Moreira, B.; da Cruz dos Anjos, D.M.; Pereira, D.S.; Sampaio, R.F.; Pereira, L.S.M.; Dias, R.C.; Kirkwood, R.N. The Geriatric Depression Scale and the Timed up and Go Test Predict Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Elderly Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (n = 103) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 81.9 ± 5.6 |

| Sex | |

| female | 66 (64.1%) |

| male | 37 (35.9%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 88 (85.4%) |

| Current fracture | 50 (48.5%) |

| Coronary heart disease | 36 (35.0%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 35 (34.0%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (32.0%) |

| Heart failure | 30 (29.1%) |

| Carcinoma/Tumor/Leukemia/Lymphoma | 25 (24.3%) |

| Osteoporosis | 17 (16.5%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16 (15.5%) |

| Structural brain lesion ‡ | 14 (13.6%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 12 (11.7%) |

| Rheumatic diseases and conditions | 6 (5.8%) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 4 (3.9%) |

| Asthma | 3 (2.9%) |

| Functional assessments | |

| Barthel Index upon admission † | 55 (45–65) |

| Barthel Index at discharge † | 80 (62.5–85) |

| Timed Up and Go Test upon admission † | 4 (3–4) |

| Timed Up and Go Test at discharge † | 3 (2–4) |

| Tinetti Balance and Gait Test upon admission † | 14 (8–18) |

| Tinetti Balance and Gait Test at discharge † | 20 (14–23) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale † | 3 (2–6) |

| Mini Mental State Examination † | 28 (27–29) |

| Shulman’s Clock-Drawing Test † | 2 (2–3) |

| Hospital stay | |

| Hospitalization (days) † | 16 (16–18) |

| Treatment units † | 21 (20–26) |

| Assessment | Admission | Discharge | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

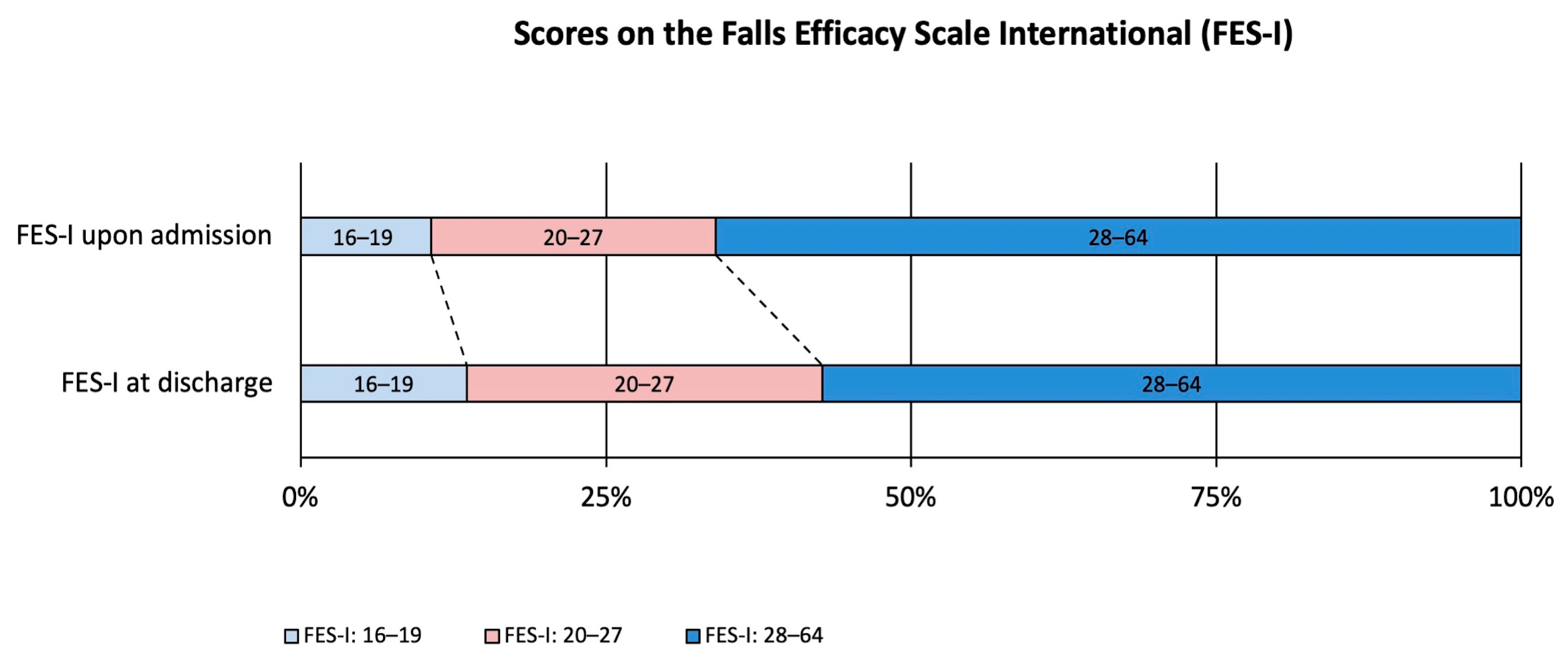

| Falls Efficacy Scale International † | 31 (23.5–40) | 30 (23.5–38) | <0.001 |

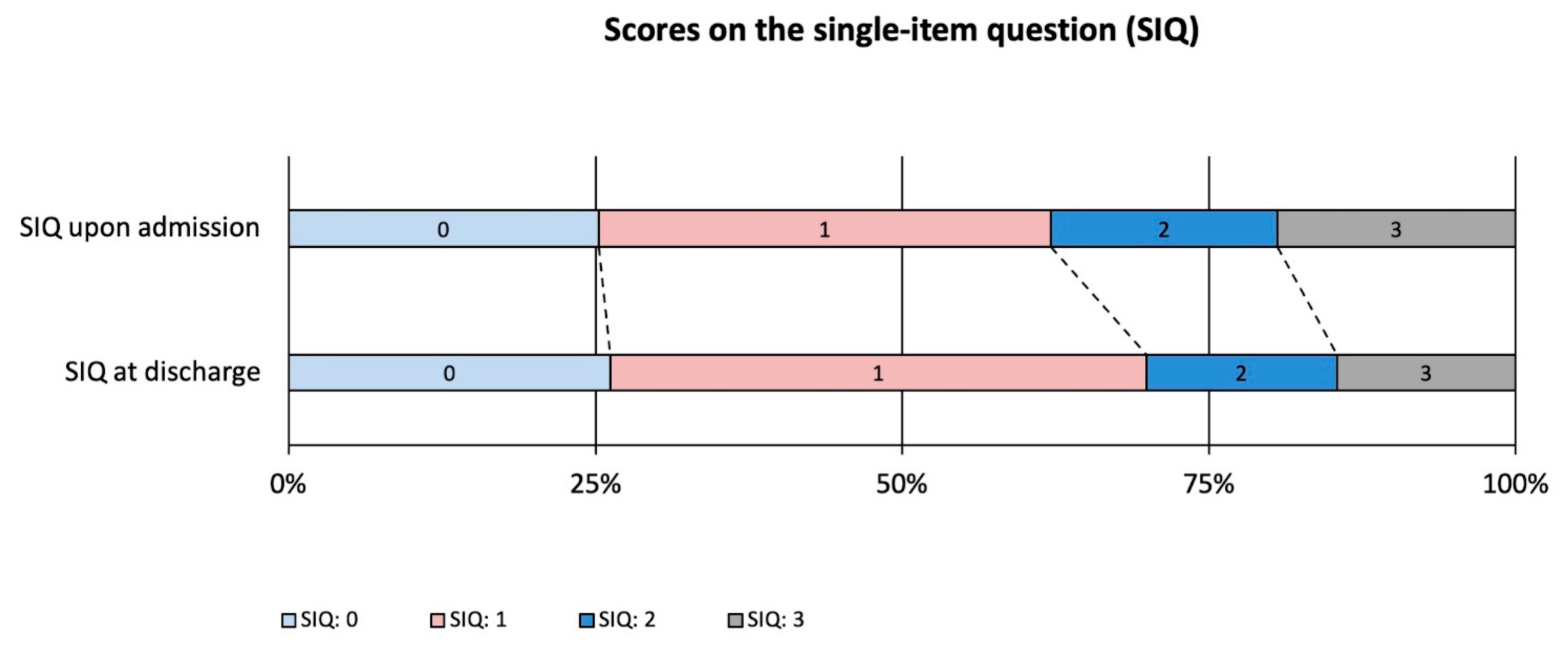

| Single-item question † | 1 (0.5–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.188 |

| Barthel Index † | 55 (45–65) | 80 (62.5–85) | <0.001 |

| Timed Up and Go Test † | 4 (3–4) | 3 (2–4) | <0.001 |

| Tinetti Balance and Gait Test † | 14 (8–18) | 20 (14–23) | <0.001 |

| Δ FES-I | Δ SIQ | Δ BI | Δ TBGT | Δ TUG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ FES-I | Spearman’s rho | |||||

| p-value | ||||||

| Δ SIQ | Spearman’s rho | 0.535 *** | ||||

| p-value | <0.001 | |||||

| Δ BI | Spearman’s rho | 0.091 | 0.106 | |||

| p-value | 0.360 | 0.286 | ||||

| Δ TBGT | Spearman’s rho | −0.073 | −0.081 | 0.298 ** | ||

| p-value | 0.463 | 0.418 | 0.002 | |||

| Δ TUG | Spearman’s rho | −0.014 | −0.042 | −0.376 *** | −0.543 *** | |

| p-value | 0.886 | 0.672 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Variables | Estimate | Standard Error | Z | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Sex (Female) | 0.70 | 0.46 | 1.51 | 0.130 | 2.01 | 0.81 | 4.94 |

| Heart failure | 1.29 | 0.52 | 2.46 | 0.014 | 3.63 | 1.30 | 10.11 |

| TBGT score ≤ 18 prior to CGC | 0.86 | 0.55 | 1.59 | 0.113 | 2.37 | 0.82 | 6.91 |

| Depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 6) | 1.29 | 0.52 | 2.47 | 0.014 | 3.61 | 1.30 | 10.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meyer, M.; Arnold, A.; Stein, T.; Niemöller, U.; Tanislav, C. Fear of Falling in Older Adults Undergoing Comprehensive Geriatric Care: Results of a Prospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124366

Meyer M, Arnold A, Stein T, Niemöller U, Tanislav C. Fear of Falling in Older Adults Undergoing Comprehensive Geriatric Care: Results of a Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124366

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeyer, Marco, Andreas Arnold, Thomas Stein, Ulrich Niemöller, and Christian Tanislav. 2025. "Fear of Falling in Older Adults Undergoing Comprehensive Geriatric Care: Results of a Prospective Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124366

APA StyleMeyer, M., Arnold, A., Stein, T., Niemöller, U., & Tanislav, C. (2025). Fear of Falling in Older Adults Undergoing Comprehensive Geriatric Care: Results of a Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124366