Are There Benefits to Observation Units in the Emergency Departments: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

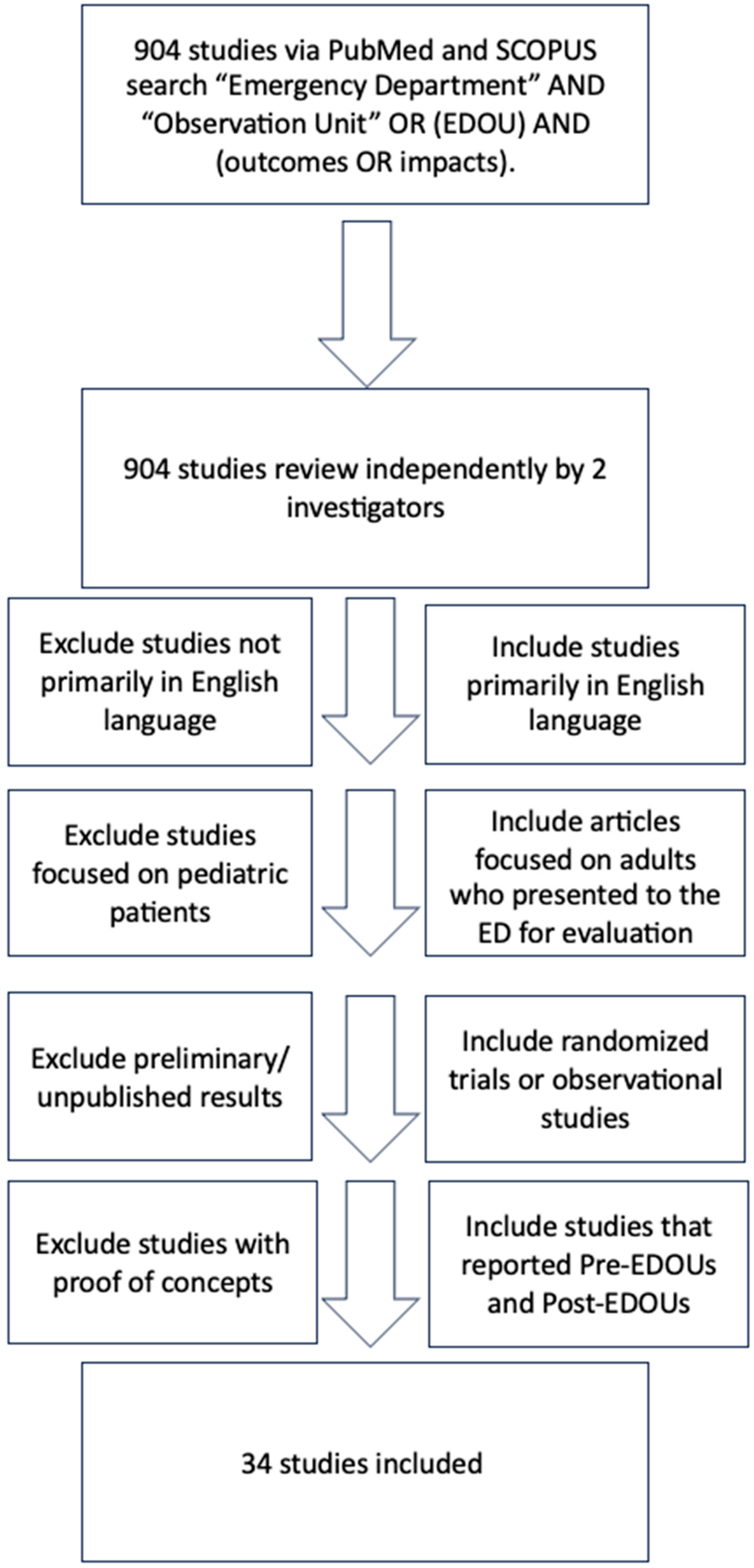

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Emergency Department Length of Stay

3.2. Rates of Hospital Admission

3.3. Returning to the ED Within 7 Days

4. Discussion

4.1. Reduction in Costs

4.2. Potential Challenges in the Implementation of EDOUs

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Actionable Items for Future EDOU Research and Implementation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cairns, C.; Ashman, J.J.; King, J.M. Emergency Department Visit Rates by Selected Characteristics: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief 2023, 478, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ohaiba, M.M.; Anamazobi, E.G.; Okobi, O.E.; Aguda, K.; Chukwu, V.U. Trends and Patterns in Emergency Department Visits: A Comprehensive Analysis of Adult Data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Database. Cureus 2024, 16, e66059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J.F.; Chang, B.C.; Hemmert, K.C. Factors Affecting Emergency Department Crowding. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 38, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Emergency Physicians Practice Guideline. Definition of Boarded Patient. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2011, 57, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanmonod, D.; Jeanmonod, R. Overcrowding in the emergency department and patient safety. Vignettes Patient Saf. 2018, 2, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D.B. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 184, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savioli, G.; Ceresa, I.F.; Gri, N.; Bavestrello Piccini, G.; Longhitano, Y.; Zanza, C.; Piccioni, A.; Esposito, C.; Ricevuti, G.; Bressan, M.A. Emergency Department Overcrowding: Understanding the Factors to Find Corresponding Solutions. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Wheatley, M.; Helen, L.M.D.; Matthew, W.M.D.; On Behalf of the SAEM ED Admin and Clinical Operations Committee. Emergency Department Observation Units; SAEM: Des Plaines, IL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.saem.org/publications/saem-publications/toolkits/boarding-and-crowding-toolkit/emergency-department-observation-units#:~:text=EDOUs%20allow%20providers%20to%20decompress,but%20cannot%20be%20discharged%20immediately (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Trecartin, K.W.; Wolfe, R.E. Emergency department observation implementation guide. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2023, 4, e13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Hagan, J.L.; Adekunle-Ojo, A.O. Managing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in the Emergency Department Observation Unit. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2019, 35, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, M.A.; Kapil, S.; Lewis, A.; O’Sullivan, J.W.; Armentrout, J.; Moran, T.P.; Osborne, A.; Moore, B.L.; Morse, B.; Rhee, P.; et al. Management of Minor Traumatic Brain Injury in an ED Observation Unit. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 22, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.; Cyrus, J.; Lilova, R.L.; Kandlakunta, S.; Aurora, T. Emergency department observation units: A scoping review. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelen, G.D.; Scheulen, J.J.; Hill, P.M. Effect of an emergency department (ED) managed acute care unit on ED overcrowding and emergency medical services diversion. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2001, 8, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbatini, A.K.; Wright, B.; Hall, M.K.; Basu, A. The cost of observation care for commercially insured patients visiting the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, A.; Guzman, B.; Hassan, A.; Borawski, J.; Harrison, D.; Manandhar, P.; Erkanli, A.; Limkakeng, A., Jr. Untapped potential for emergency department observation unit use: A National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) study. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 23, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, B.; Sunny, S.; Kettyle, P.; Chacko, J.; Stefanov, D.G. Characteristics of patients who return to the emergency department after an observation-unit assessment. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2024, 11, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Franks, N.; Pitts, S.R.; Moran, T.P.; Osborne, A.; Peterson, D.; Ross, M.A. The impact of emergency department observation units on a health system. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 48, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.A.; Compton, S.; Richardson, D.; Jones, R.; Nittis, T.; Wilson, A. The use and effectiveness of an emergency department observation unit for elderly patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2003, 41, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schull, M.J.; Vermeulen, M.J.; Stukel, T.A.; Guttmann, A.; Leaver, C.A.; Rowe, B.H.; Sales, A. Evaluating the effect of clinical decision units on patient flow in seven Canadian emergency departments. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2012, 19, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.H.Y.; Barclay, N.G.; Abu-Laban, R.B. Effect of a Multi-Diagnosis Observation Unit on emergency department length of stay and inpatient admission rate at two Canadian hospitals. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 51, 739–747.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.; Sturgis, L.; Loeffler, P.; Kuckinski, A.-M.; Kutlar, A.; Gibson, R.; Lyon, M. Emergency Department Physicians Management Versus Hospitalists Service Management Admittance Rates for Sickle Cell Disease Patients from an Emergency Department Observation Unit. Blood 2015, 126, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.K.; Geisler, B.P.; Gibson Chambers, J.J.; Baugh, C.W.; Bohan, J.S.; Schuur, J.D. Use of Observation Care in US Emergency Departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brillman, J.C.; Tandberg, D. Observation unit impact on ED admission for asthma. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1994, 12, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blecker, S.; Gavin, N.P.; Park, H.; Ladapo, J.A.; Katz, S.D. Observation units as substitutes for hospitalization or home discharge. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2015, 67, 706–713.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.; Graff, L.G. 4th Economic issues in observation unit medicine. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 19, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mace, S.E.; Graff, L.; Mikhail, M.; Ross, M. A national survey of observation units in the United States. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 21, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwani, V.; Tinloy, B.; Ulrich, A.; D’Onofrio, G.; Goldenberg, M.; Rothenberg, C.; Patel, A.; Venkatesh, A.K. Opening of Psychiatric Observation Unit Eases Boarding Crisis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southerland, L.T.; Simerlink, S.R.; Vargas, A.J.; Krebs, M.; Nagaraj, L.; Miller, K.N.; Adkins, E.J.; Barrie, M.G. Beyond observation: Protocols and capabilities of an Emergency Department Observation Unit. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.A.; Hockenberry, J.M.; Mutter, R.; Barrett, M.; Wheatley, M.; Pitts, S.R. Protocol-Driven emergency department observation units offer savings, shorter stays, and reduced admissions. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarey, A.W.; Weng, J.; Looi, J.C.L.; Allison, S.; Bastiampillai, T. Systematic review of psychiatric observation units and their impact on emergency department boarding. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2023, 25, 49818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, P.; Lenzi, T. Effectiveness of a multipurpose observation unit: Before and after study. Emerg. Med. J. 2009, 26, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aplin, K.S.; McAllister, S.C.; Kupersmith, E.; Rachoin, J. Caring for patients in a hospitalist-run clinical decision unit is associated with decreased length of stay without increasing revisit rates. J. Hosp. Med. 2014, 9, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Komindr, A.; Baugh, C.W.; Grossman, S.A.; Bohan, J.S. Key operational characteristics in emergency department observation units: A comparative study between sites in the United States and Asia. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Capp, R.; Sun, B.; Boatright, D.; Gross, C. The impact of emergency department observation units on United States emergency department admission rates. J. Hosp. Med. 2015, 10, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, L.; Zun, L.S.; Leikin, J.; Gibler, B.; Weinstock, M.S.; Mathews, J.; Benjamin, G.C. Emergency department observation beds improve patient care: Society for Academic Emergency Medicine debate. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1992, 21, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, B.E.; Richter, K.M.; Youngblood, L.; Cohen, B.A.; Prengler, I.D.; Cheng, D.; Masica, A.L. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J. Hosp. Med. 2009, 4, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuckols, T.K.; Fingar, K.R.; Barrett, M.L.; Martsolf, G.; Steiner, C.A.; Stocks, C.; Owens, P.L. Returns to Emergency Department, Observation, or Inpatient Care Within 30 Days After Hospitalization in 4 States, 2009 and 2010 Versus 2013 and 2014. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 13, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, R.B.; Sheingold, S.H.; Orav, E.J.; Ruhter, J.; Epstein, A.M. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Roberge, J.; Moore, C.G.; Ashby, A.; Rossman, W.; Murphy, S.; McCall, S.; Brown, R.; Carpenter, S.; Rissmiller, S.; et al. Aiming to Improve Readmissions Through InteGrated Hospital Transitions (AIRTIGHT): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016, 17, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, D.M.; Silva, S.; Freiermuth, C.E.; Thornton, V.; Tanabe, P. Emergency Department (ED), ED Observation, Day Hospital, and Hospital Admissions for Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 19, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, B.; Leikin, J.B.; Timmons, J.A.; Hanashiro, P.K.; Kissane, K. Patterns of use of an Emergency Department-Based Observation Unit. Am. J. Ther. 2002, 9, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southerland, L.T.; Vargas, A.J.; Nagaraj, L.; Gure, T.R.; Caterino, J.M. An Emergency Department Observation Unit Is a Feasible Setting for Multidisciplinary Geriatric Assessments in Compliance with the Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevan, M.; Graff, L. Observation medicine and clinical decision units. In Elsevier eBooks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 2521–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaftari, P.; Lipe, D.N.; Wattana, M.K.; Qdaisat, A.; Krishnamani, P.P.; Thomas, J.; Elsayem, A.F.; Sandoval, M. Outcomes of patients placed in an emergency department observation unit of a comprehensive cancer center. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 18, e574–e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.A.; Hemphill, R.R.; Abramson, J.; Schwab, K.; Clark, C. The recidivism characteristics of an emergency department observation unit. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010, 56, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastry, S.; Yeo, J.; Richardson, L.D.; Manini, A.F. Observation unit management of low-risk emergency department patients with acute drug overdose. Clin. Toxicol. 2019, 58, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.; King, S.; Caldwell, C.; Soto, E.F.; Chambers, A.; Boehmer, S.; Gopaul, R. Returns after discharge from the emergency Department observation unit: Who, what, when, and why? West. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 24, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Study Type | Primary Outcome(s) | Secondary Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mueller et al., 2015 [21] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Hospitalists managed sickle cell disease patients in an EDOU at a significantly higher admittance rate than ED physicians, but no significant difference in three-day return rates was found [21]. | The average EDOU length of stay (LOS) for a sickle cell disease patient during the ED management period was 17 h and 54 min, while the average LOS during hospitalist management was 18 h and 23 min. The 30-day return rates for patients who did not return at three days were not significantly different [21]. |

| Venkatesh et al., 2011 [22] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Observation care in U.S. EDs increased from 0.60% to 1.87% of visits between 2001 and 2008. Chest pain was the most common condition evaluated. One-third of hospitals had dedicated observation units by 2008 [22]. | |

| J. Brillman et al., 1994 [23] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Observation units (OUs) in EDs for asthmatic patients result in lower initial discharge rates but do not significantly reduce hospital admissions [23]. | |

| Schull et al., 2012 [19] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Clinical decision units in emergency departments can slightly reduce ED length of stay, admission rates, and no increase in ED revisit rates [19]. | Clinical decision units were associated with reducing the length of stay for low-acuity and non-admitted patients [19]. |

| Blecker et al., 2016 [24] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Increased observation unit availability may result in decreased hospitalizations and decreased home discharges for chest pain patients [24]. | None |

| R. Roberts et al., 2001 [25] | N/A | Observation medicine in EDs improves resource utilization and patient care, with flexibility and creative solutions being key to successful implementation [25]. | |

| Mace et al., 2003 [26] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Those hospitals that had OUs had a higher overall ED census, higher rate of diversion of ambulances, and were more likely to be in metropolitan areas, but there was no relationship to payor mix or to ED hospital admission rate [26]. | |

| Cheng et al., 2016 [20] | Non-RCT Observational Study | A multi-diagnosis OU can reduce hospital admission rates, but does not significantly decrease ED length of stay [20]. | |

| Perry et al., 2021 [17] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Within an academic medical center, EDOUs were associated with improved resource utilization and reduced cost. This represents a significant opportunity for hospitals to improve efficiency and contain costs [17]. | Observation patients managed in an EDOU within an academic health system experienced shorter lengths of stay [17]. |

| Parwana et al., 2018 [27] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Acute psychiatric OUs reduce ED boarding and length of stay, supporting efficient allocation of scarce inpatient psychiatric beds [27]. | |

| Southerland et al., 2019 [28] | Non-RCT Observational Study | An EDOU can effectively care for a wide variety of patients requiring multiple consultations, procedures, and care coordination while maintaining an acceptable length of stay and admission rate [28]. | |

| Ross et al., 2013 [29] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Type 1 OUs in EDs lead to shorter stays, lower inpatient admission rates, and potential annual savings of USD 5.5–8.5 billion [29]. | |

| Ross et al., 2003 [18] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Elderly patients in EDOUs have effective lengths of stay and hospital admission rates, with comparable return visit rates to younger patients [18]. | |

| Magarey et al., 2023 [30] | Systematic Review | Psychiatric OUs may reduce ED wait times for patients with mental health presentations, but more research is needed to confirm this [30]. | Based on limited, poor-quality evidence, ED units may reduce LOS for patients with crisis mental health presentations [30]. |

| Iannone et al., 2009 [31] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Short OUs in EDs benefit from proper organization and standardized clinical pathways, reducing re-admissions and hospitalizations [31]. | Patients admitted to the short OU (SOU) from the ED had a shorter length of stay. Within 3 months post-discharge from the SOU, rates of ED visits and hospitalizations declined, while SOU re-admissions remained unchanged [31]. |

| Kelen et al., 2001 [13] | Non-RCT Observational Study | An ED-managed acute care unit can significantly impact ED overcrowding and ambulance diversion, with no need for it to be proximate to the ED [13]. | |

| Aplin et al., 2014 [32] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Implementing a hospitalist-run geographic CDU significantly reduced observation stay length without increasing ED or hospital revisit rates [32]. | None |

| Komindr et al., 2014 [33] | Non-RCT Observational Study | EDOUs can improve efficiency and patient satisfaction by reducing length of stay, increasing bed turnover, and increasing discharge rates across both US and Asian sites [33]. | None |

| Capp et al., 2015 [34] | Non-RCT Observational Study | The presence of EDOUs did not show a statistically significant decrease in ED hospital admission rates [34]. | |

| Graff et al., 1992 [35] | Discussion Article | OUs in EDs improve patient care and help manage common emergencies, while contributing to the healthcare crisis and reducing costs [35]. | |

| Koehler et al., 2009 [36] | Randomized controlled pilot study | A targeted care bundle for high-risk elderly inpatients reduced unplanned acute healthcare utilization up to 30 days after discharge, but this effect dissipated by 60 days post-discharge [36]. | |

| Nuckols et al., 2017 [37] | Epidemiological analysis | Total returns to the hospital are stable or rising, likely due to growth in observation and ED visits [37]. | |

| Zuckerman et al., 2016 [38] | Interrupted time-series analysis. | Hospitals have reduced readmission rates due to financial penalties under the ACA, but observation-unit stays did not significantly contribute to the decrease in readmissions [38]. | |

| McWilliams et al., 2016 [39] | Randomized controlled trial | An integrated practice unit, called transition services, may reduce 30-day readmission rates for high-risk hospitalized patients [39]. | |

| Cline et al., 2018 [40] | Prospective Cohort | Sickle cell anemia patients’ healthcare utilization varies significantly, with one cohort having more hospital admissions and ED encounters, while the other cohort had more day hospital encounters and used a sickle cell disease observation VOC protocol [40]. | |

| Navas et al., 2022 [15] | Cross-sectional analysis | EDOUs services for suspected acute coronary syndrome are underused, with over half of potentially observation-amenable admissions paid for by Medicare and Medicaid [15]. | None |

| Hostetler et al., 2002 [41] | Observational Retrospective Review | EDOUs can be a valuable tool for assessing and treating patients with questionable admitting criteria, but are not a substitute for inpatient units [42]. | |

| Southerland et al., 2018 [42] | Observational Retrospective Review | An EDOU is a feasible setting for multidisciplinary geriatric assessments, resulting in targeted interventions and shorter lengths of stay [43]. | |

| Mahadevan et al., 2010 [43] | Comprehensive Review | Observation services in EDs can reduce hospitalization costs and increase patient discharge without needing hospitalization, benefiting selected patients with critical diagnostic syndromes and emergency conditions [43]. | |

| Hahn et al., 2024 [16] | Retrospective Cohort Study | The study identifies factors contributing to patients’ return to the ED post-observation, emphasizing the need for improved follow-up and discharge planning to reduce these returns [16]. | |

| Chaftari et al., 2021 [44] | Non-RCT Observational Study | Placing cancer patients in EDOUs is safe, reduces admissions, and conserves hospital resources without compromising care [44]. | Placing discharged ED patients in the EDOU instead may potentially lead to fewer short-term revisits [44]. |

| Ross et al., 2010 [45] | Non-RCT Observational Study | EDOUs recidivism rates differ by observation category, with painful conditions showing the highest recidivism rates [45]. | |

| Shastry et al., 2020 [46] | Non-RCT Observational Study | OUs can safely manage low-risk drug overdose patients in EDs, with acceptable adverse event rates [46]. | |

| Baerger et al., 2013 [47] | Non-RCT Observational Study | The overall return rate from EDOUs is under 10%, with two-thirds of returns related to the index visit and 5% potentially avoidable [47]. |

| Category | Primary Findings | Main Takeaway | Limitation(s) | Future Direction(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDLOS |

|

|

|

|

| Rate of Hospital Admission |

|

|

|

|

| Return to ED in 7 Days |

|

|

|

|

| Reduction in Costs |

|

|

|

|

| Challenges in Implementation |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leggett, E.; Haan, S.; Mendoza, C.; Pourmand, A.; Sommerkamp, S.; Chasm, R.; Adler, J.; Bond, M.C.; Tran, Q.K. Are There Benefits to Observation Units in the Emergency Departments: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124333

Leggett E, Haan S, Mendoza C, Pourmand A, Sommerkamp S, Chasm R, Adler J, Bond MC, Tran QK. Are There Benefits to Observation Units in the Emergency Departments: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124333

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeggett, Emmeline, Shirin Haan, Carolina Mendoza, Ali Pourmand, Sarah Sommerkamp, Rose Chasm, Jason Adler, Michael C. Bond, and Quincy K. Tran. 2025. "Are There Benefits to Observation Units in the Emergency Departments: A Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124333

APA StyleLeggett, E., Haan, S., Mendoza, C., Pourmand, A., Sommerkamp, S., Chasm, R., Adler, J., Bond, M. C., & Tran, Q. K. (2025). Are There Benefits to Observation Units in the Emergency Departments: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124333