The Experience of Frail Older Patients in the Boarding Area in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Inclusion Criteria

3.1. Types of Participants

3.2. Phenomenon of Interest

3.3. Context

3.4. Types of Studies

4. Search Strategy and Study Selection

4.1. Assessment of Methodological Quality

4.2. Data Extraction

4.3. Data Synthesis

5. Results

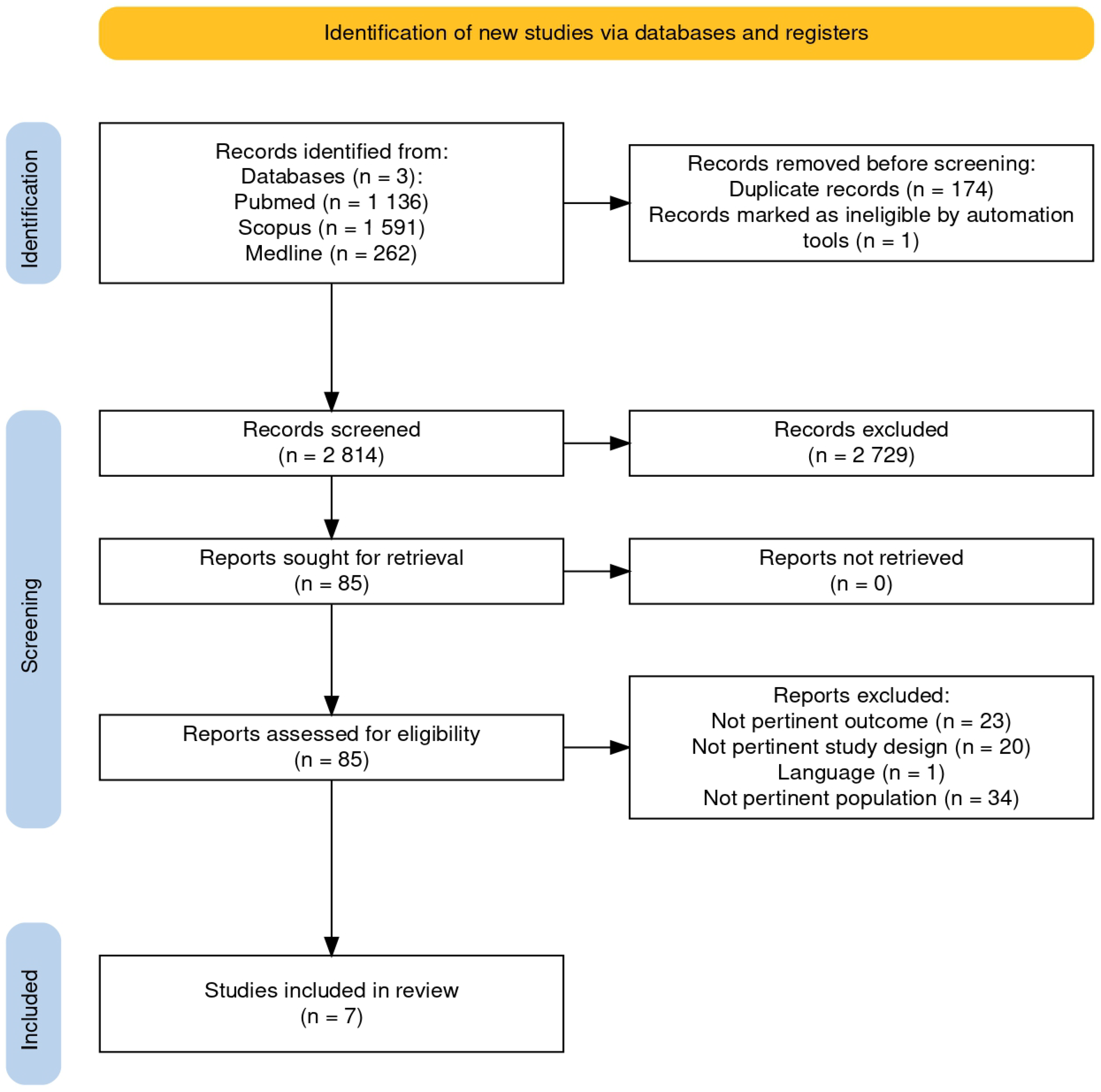

5.1. Search Results

5.2. Meta-Aggregation

5.3. THEME 1: Waiting Time Among Frail Older Patients Typically Generates Discomfort, Distress, and Frustration

5.3.1. Discomfort

5.3.2. Distress

5.3.3. Frustration

5.4. THEME 2: Experience with Positive and Negative Attitudes of Healthcare Providers

5.4.1. Lack of Empathy Among Health Professionals

5.4.2. Lack of Communication

5.5. THEME 3: Supportive Role of Family Members During ED LOS

5.5.1. Involvement of Family Members

5.5.2. Frail Older Patient Experience of Boarding Improved by Family Members

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Implication for Clinical Practice

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy Until 31 October 2024

| PUBMED MEDLINE SCOPUS |

| (boarding OR length of stay) AND (emergency department OR emergency room OR emergency service) AND (elderly OR older adults) AND (experience OR patient experience OR patient satisfaction OR psychological impact OR patient perceptions) (“boarded”[All Fields] OR “boarding”[All Fields] OR (“length of stay”[MeSH Terms] OR (“length”[All Fields] AND “stay”[All Fields]) OR “length of stay”[All Fields])) AND (“emergency service, hospital”[MeSH Terms] OR (“emergency”[All Fields] AND “service”[All Fields] AND “hospital”[All Fields]) OR “hospital emergency service”[All Fields] OR (“emergency”[All Fields] AND “department”[All Fields]) OR “emergency department”[All Fields] OR(“emergency service, hospital”[MeSH Terms] OR (“emergency”[All Fields] AND “service”[All Fields] AND “hospital”[All Fields]) OR “hospital emergency service”[All Fields] OR (“emergency”[All Fields] AND “room”[All Fields]) OR “emergency room”[All Fields]) OR (“emergency medical services”[MeSH Terms] OR (“emergency”[All Fields] AND “medical”[All Fields] AND “services”[All Fields]) OR “emergency medical services”[All Fields] OR (“emergency”[All Fields] AND “service”[All Fields]) OR “emergency service”[All Fields])) AND (“aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “aged”[All Fields] OR “elderly”[All Fields] OR “elderlies”[All Fields] OR “elderly s”[All Fields] OR “elderlys”[All Fields] OR (“aged”[MeSH Terms] OR “aged”[All Fields] OR (“older”[All Fields] AND “adults”[All Fields]) OR “older adults”[All Fields])) AND (“experience”[All Fields] OR “experience s”[All Fields] OR “experiences”[All Fields] OR ((“patient s”[All Fields] OR “patients”[MeSH Terms] OR “patients”[All Fields] OR “patient”[All Fields] OR “patients s”[All Fields]) AND (“experience”[All Fields] OR “experience s”[All Fields] OR “experiences”[All Fields])) OR (“patient satisfaction”[MeSH Terms] OR (“patient”[All Fields] AND “satisfaction”[All Fields]) OR “patient satisfaction”[All Fields]) OR ((“psychologic”[All Fields] OR “psychological”[All Fields] OR “psychologically”[All Fields] OR “psychologization”[All Fields] OR “psychologized”[All Fields] OR “psychologizing”[All Fields]) AND (“impact”[All Fields] OR “impactful”[All Fields] OR “impacting”[All Fields] OR “impacts”[All Fields] OR “tooth, impacted”[MeSH Terms] OR (“tooth”[All Fields] AND “impacted”[All Fields]) OR “impacted tooth”[All Fields] OR “impacted”[All Fields])) OR ((“patient s”[All Fields] OR “patients”[MeSH Terms] OR “patients”[All Fields] OR “patient”[All Fields] OR “patients s”[All Fields]) AND (“percept”[All Fields] OR “perceptibility”[All Fields] OR “perceptible”[All Fields] OR “perception”[MeSH Terms] OR “perception”[All Fields] OR “perceptions”[All Fields] OR “perceptional”[All Fields] OR “perceptive”[All Fields] OR “perceptiveness”[All Fields] OR “percepts”[All Fields]))) |

References

- Burgess, L.; Ray-Barruel, G.; Kynoch, K. Association between emergency department length of stay and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Res. Nurs. Health 2022, 45, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, Y.; Gholipour, C.; Aghazadeh, J.; Khanahmadi, S.; Beygzadeh, T.; Nouri, D.; Nahaei, M.; Karimi, R.; Hosseinalipour, E. Evaluation of the risk factors associated with emergency department boarding: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Chin. J. Traumatol. Engl. Ed. 2020, 23, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, R.C.; Shufflebarger, E.F.; Booth, J.S.; Walter, L.A. Race and Other Disparate Demographic Variables Identified Among Emergency Department Boarders. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 23, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iozzo, P.; Spina, N.; Cannizzaro, G.; Gambino, V.; Patinella, A.; Bambi, S.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Latina, R. Association between Boarding of Frail Individuals in the Emergency Department and Mortality: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Shang, N.; Chhetri, J.K.; Liu, L.; Guo, W.; Li, P.; Guo, S.; Ma, L. A Frailty Screening Questionnaire (FSQ) to Rapidly Predict Negative Health Outcomes of Older Adults in Emergency Care Settings. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.; Lewis, E.T.; Kristensen, M.R.; Skjøt-Arkil, H.; Ekmann, A.A.; Nygaard, H.H.; Jensen, J.J.; Jensen, R.O.; Pedersen, J.L.; Turner, R.M.; et al. Predictive validity of the CriSTAL tool for short-term mortality in older people presenting at Emergency Departments: A prospective study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 9, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, C.S.; Trappenburg, M.C.; ter Wee, M.M.; Hoogendijk, E.O.; de Vet, H.C.; Smulders, Y.M.; Nanayakkara, P.W.; Muller, M.; Peters, M.J. The Accuracy of Four Frequently Used Frailty Instruments for the Prediction of Adverse Health Outcomes Among Older Adults at Two Dutch Emergency Departments: Findings of the AmsterGEM Study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venema, D.; Vervoort, S.C.J.M.; de Man-van Ginkel, J.M.; Bleijenberg, N.; Schoonhoven, L.; Ham, W.H.W. What are the needs of frail older patients in the emergency department? A qualitative study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2023, 67, 101263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peña, C.; Pérez-Zepeda, M.U.; Robles-Jiménez, L.V.; Sánchez-García, S.; Ramírez-Aldana, R.; Tella-Vega, P. Mortality and associated risk factors for older adults admitted to the emergency department: A hospital cohort. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarek, L.; Maillet, F.; Turki, A.; Altar, A.; Hamdi, H.; Berroukeche, M.; Haguenauer, D.; Chemouny, M.; Cailleaux, P.-E.; Javaud, N. Prognosis of non-severely comorbid elderly patients admitted to emergency departments: A prospective study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2034–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleheie, I.; Debesay, J.; Bye, A.; Bergland, A. A qualitative study of old patients’ experiences of the quality of the health services in hospital and 30 days after hospitalization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 2020–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z.E. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Lewis, S.; Evans, L.; Rainer, T.; Hewitt, J. Screening for frailty in older emergency patients and association with outcome. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, A.T.; Melnick, E.R.; Venkatesh, A.K. Hospital Occupancy and Emergency Department Boarding during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, E2233964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.W.; Rosen, A.; Kennedy, M. Boarding in the Emergency Department: Specific Harms to Older Adults and Strategies for Risk Mitigation. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 43, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, J.; Cetin-Sahin, D.; Cossette, S.; Ducharme, F.; Vadeboncoeur, A.; Vu, T.T.M.; Veillette, N.; Ciampi, A.; Belzile, E.; Berthelot, S.; et al. How Older Adults Experience an Emergency Department Visit: Development and Validation of Measures. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 71, 755–766.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Smith, J.E.; Nelmes, P.; Squire, R.; Latour, J.M. Initial Development of a Patient Reported Experience Measure for Older Adults Attending the Emergency Department: Part I—Interviews with Service Users. Healthcare 2023, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issahaku, P.A.; Sulemana, A. Older Adults’ Expectations and Experiences With Health care Professionals in Ghana. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211040125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlgren, A.L.; Nilsson, M.; Skovdahl, K.; Palmblad, B.; Wimo, A. Older patients awaiting emergency department treatment. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakilasa, M.T.; Foley, C.; O’carroll, T.; Flynn, R.; Rohde, D. Care Experiences of Older People in the Emergency Department: A Concurrent Mixed-Methods Study. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 23743735211065267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppala, M.; Ezeana, C.F.; Alvarado, M.V.Y.; Goode, K.N.; Danforth, R.L.; Wong, S.S.; Vassallo, M.L.; Wong, S.T. A multifaceted study of hospital variables and interventions to improve inpatient satisfaction in a multi-hospital system. Medicine 2020, 99, E23669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassarino, M.; Robinson, K.; Trépel, D.; O’shaughnessy, Í.; Smalle, E.; White, S.; Devlin, C.; Quinn, R.; Boland, F.; Ward, M.E.; et al. Impact of assessment and intervention by a health and social care professional team in the emergency department on the quality, safety, and clinical effectiveness of care for older adults: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, M.; Berry, D.; Considine, J. Frequent Use of Emergency Departments by Older People: A Comparative Cohort Study of Characteristics and Outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2018, 30, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntlin, Å.; Gunningberg, L.; Carlsson, M. Patients’ Perceptions of Quality of Care at an Emergency Department and Identification of Areas for Quality Improvement. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, U.; Shah, M.N.; Han, J.H.; Carpenter, C.R.; Siu, A.L.; Adams, J.G. Transforming Emergency Care for Older Adults. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 2116–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukkonen, M.; Jämsen, E.; Zeitlin, R.; Pauniaho, S.L. Emergency Department Visits in Older Patients: A Population-Based Survey. BMC Emerg. Med. 2019, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, M.J.; e Silva, L.O.J.; Suarez, N.E.; Walker, L.E.; Erwin, P.; Carpenter, C.R.; Bellolio, F. Interventions to Improve Older Adults’ Emergency Department Patient Experience: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year), Country | Aim | Design | Sample and Setting | Methods | Experience Main Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCusker et al. (2018), [18] Canada | Evaluate older adults’ experiences of problems in the ED. | Qualitative study (focus group) | ≥75 years, ED N = 412 F = 275 | The authors used a 16-question questionnaire to assess the two dimensions (personal care/communication and waiting time). | Areas of experience that are more relevant to older people are family needs (e.g., keeping informed, participating in care), physical needs (e.g., thirst, mobilization, physical environment) and transitional care needs (e.g., patient-centerd discharge information, communication with doctor). |

| Graham et al. (2023) [19], England | The study evaluates the experience of older adult patients in the emergency department. | Qualitative study (interviews) | ≥65 years, ED N = 24 F = 15 | Using semi-structured interviews with three main questions, assessing three dimensions: patient experience, patient safety, and clinical effectiveness. | Questions exploring patient experiences of care confirmed that meeting the communication, care, waiting, physical, and environmental needs were prominent determinants of experience for older adults. |

| Issahaku& Sulemana (2021) [20], Ghana | The study evaluates the experience of older adult patients in the emergency department | Qualitative study (interviews) | ≥60 years, ED N = 23 F = 9 | Using semi-structured interviews with two main questions. The experiences of hospital visits and how they would like to be treated by health professionals are the focus of this paper. | Uncompassionate care, disrespectful attitudes, and a better way of treating us emerged as three main themes from the data. |

| Kihlgren et al. (2004) [21], Sweden | The focus of the observations was on the patients, the care they received, the family members accompanying them, and the general environment. | Pilot field study (observations) | ≥75 years, ED N = 20 F = 14 | Open, non-participant observations were conducted by following the patient from the reception area to the examination room until discharge from the ED. Four researchers each conducted one observation in the ED for the pilot study. | Selective coding resulted in six core variables that became the focus of the analysis. These variables were: uncomfortable waiting, superfluous waiting, lack of good routines while waiting, suffering while waiting, negative emotions while waiting, and care while waiting. |

| Venema et al. (2023) [8], Netherlands | The study evaluates the experience of older adult patients in the emergency department | Qualitative study (interviews) | ≥70 years, ED N = 12 F = 4 | A qualitative design was used, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with discharged twelve frail older adult patients who had been admitted to the emergency department. | The themes of feeling disturbed, expecting care, suppressing needs and wanting to be seen emerged from the analysis. These themes suggested a need for healthcare professionals to be more aware of the situation when caring for participants. This was influenced by the participants’ life experiences. |

| Mwakilasa et al. (2021) [22], Ireland | The study evaluates the experience of older adult patients in the emergency department | Mixed methods study (qualitative interview component used) | ≥ 65 years ED N = NR | This concurrent mixed-methods study involved secondary analysis of qualitative and quantitative data. | Scores for overall ED experiences were calculated from five questions that asked patients about communication, privacy, waiting time, and whether they were treated with dignity and respect in the ED. |

| Puppala et al. (2020) [23], USA | Care’s satisfaction of frail older adults. | Qualitative study (interview Survey) | ≥65 years ED N = NR | A qualitative study with the inpatient population of an eight-hospital tertiary medical center in 2015. The satisfaction determinants were based on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey answers and included clinical and organizational variables. | The older groups with the lowest satisfaction score were those admitted through the ED who experienced long waiting times or had chronic diseases. |

| Synthetized Theme | Categories | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Waiting time experience among frail older patients | Discomfort | Lack of privacy [D1] U; Sitting in a chair or lying on a bed [B1] U [D2] U; Stay near sick patient [B2]C; Crowded environment [F1] U [D3]C |

| Distressing | Long waiting time [E1] C [G1] C [F2] C [B3] U [D4] U [H1] U; Any information about treatment [F3]C; Psychological distress [F4]C | |

| Frustration | Do not know long waiting time’s reason [D5] C; Not have sense of time [D6] C; Not having personal belongings [H2] U; Physical needs [H3] U | |

| Experience with attitude of healthcare providers | Lack of empathy among health professionals | Lacking compassion [C1] C; Trustworthiness [C2] C; Disrespectful Attitude [C3] C; Perceived sense of invisibility [A1] C; Showed a great longing for contact with staff [D7] C; Staff do not have enough time to talk to patients [A2] C |

| Lack of communication | Lack of clarity and transparency about their care [B4] C; Wanting to be seen [H3] C; The level of patient satisfaction heavily depends on the adequacy of communication [G2] C; Inadequate communication [F5] U; Communication on health problem [E1] C; Use discriminatory communication [C4] C | |

| The role of family members during ED LOS | Involvement of family members | The importance of being involved in the decision-making process [B5] U; Understanding patient and family perspectives [E2] U |

| Frail older patient experience of boarding improved by family members | Lower level of social and family support [A3] C; Need assistance in basic needs [D8] U; Reduces sense of confusion [G3] U; They do not suppress their needs [H4] C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iozzo, P.; Cannizzaro, G.; Bambi, S.; Amato, L.M.; Fanuli, S.; Ivziku, D.; Anastasi, G.; Lucchini, A.; Spina, N.; Latina, R. The Experience of Frail Older Patients in the Boarding Area in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103556

Iozzo P, Cannizzaro G, Bambi S, Amato LM, Fanuli S, Ivziku D, Anastasi G, Lucchini A, Spina N, Latina R. The Experience of Frail Older Patients in the Boarding Area in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103556

Chicago/Turabian StyleIozzo, Pasquale, Giovanna Cannizzaro, Stefano Bambi, Luana Maria Amato, Simona Fanuli, Dhurata Ivziku, Giuliano Anastasi, Alberto Lucchini, Noemi Spina, and Roberto Latina. 2025. "The Experience of Frail Older Patients in the Boarding Area in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103556

APA StyleIozzo, P., Cannizzaro, G., Bambi, S., Amato, L. M., Fanuli, S., Ivziku, D., Anastasi, G., Lucchini, A., Spina, N., & Latina, R. (2025). The Experience of Frail Older Patients in the Boarding Area in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103556