Using the P-CaRES Tool to Identify Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases: An Analysis of Internal Medicine Admissions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

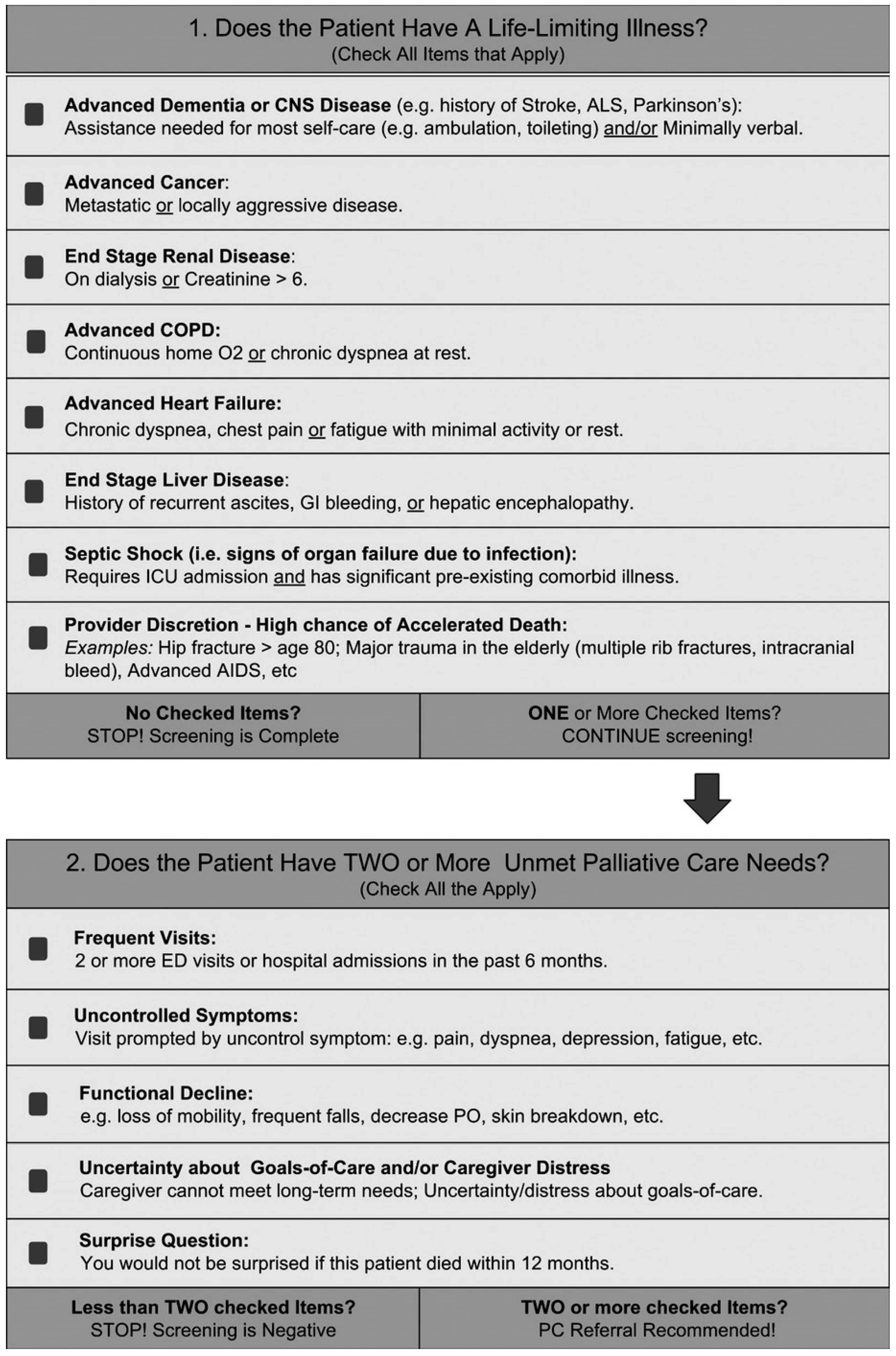

2.3. The P-CaRES Screening Tool

2.4. The Specialized PC Service at the University-Based Referral Center

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Categorical variables: chi-square or Fisher’s exact test;

- Non-normally distributed continuous variables: Mann–Whitney U test (pairwise) and Kruskal–Wallis test (multiple groups), with post-hoc analyses as needed;

- Normality: assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients

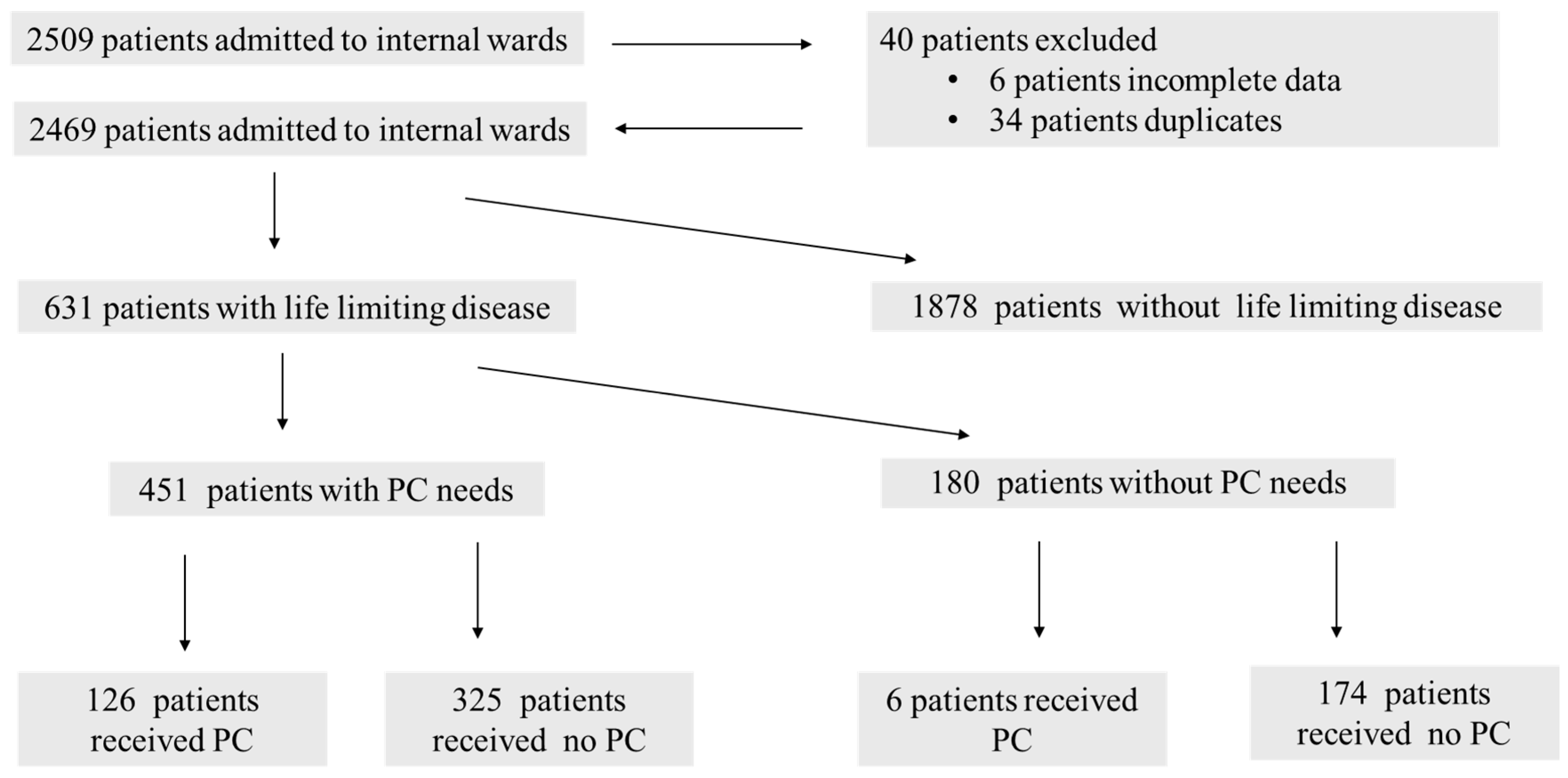

3.1.1. Patient Screening and Study Population

3.1.2. Identification and Receipt of Palliative Care

3.1.3. Demographics and Diagnoses

3.1.4. Palliative Care Indicators

3.1.5. Healthcare Utilization and Outcomes

3.1.6. Statistical Differences Across Patient Groups

3.1.7. Differences in Clinical Indicators Across Patient Groups

3.2. Multivariate Predictors of Receiving Palliative Care

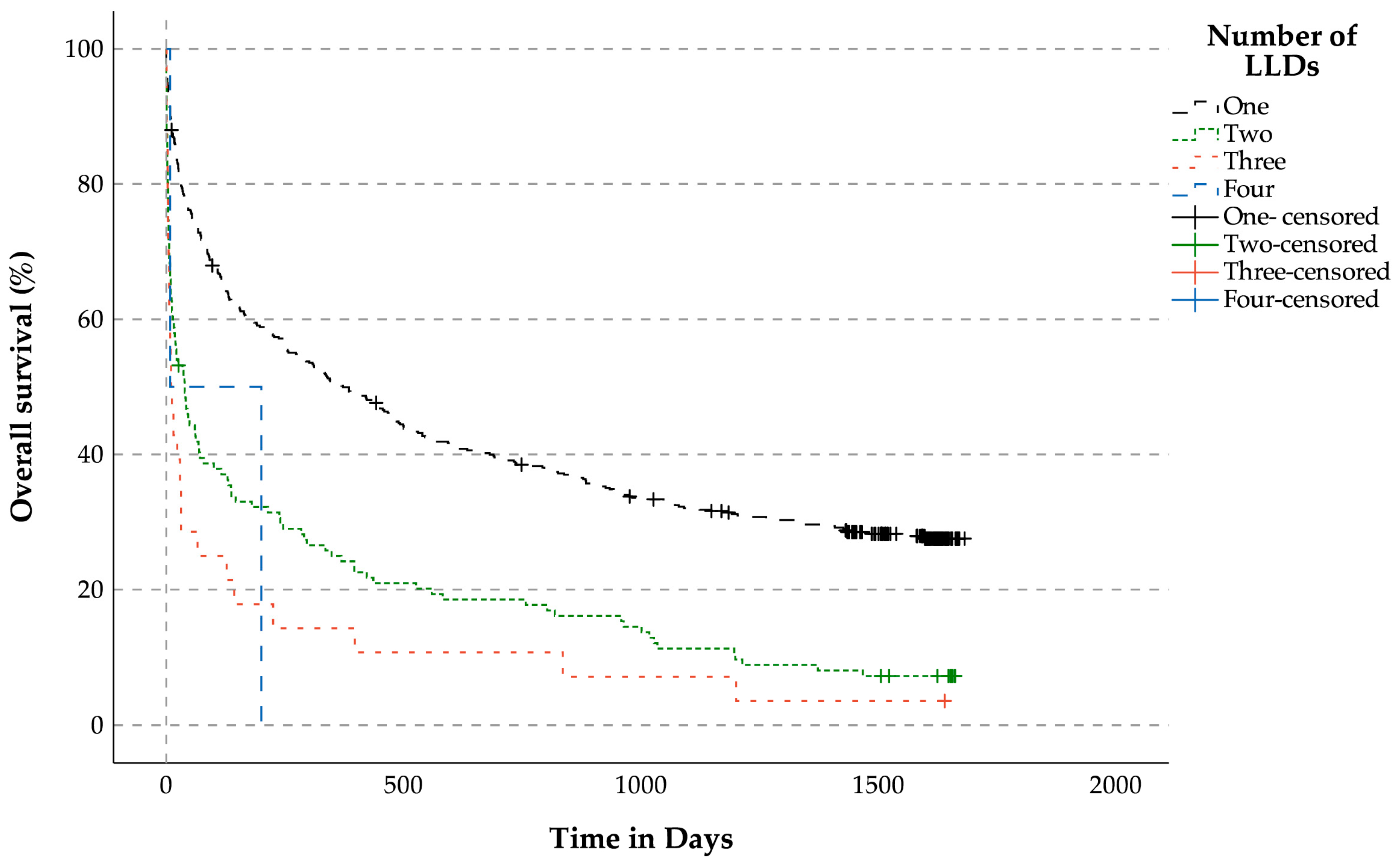

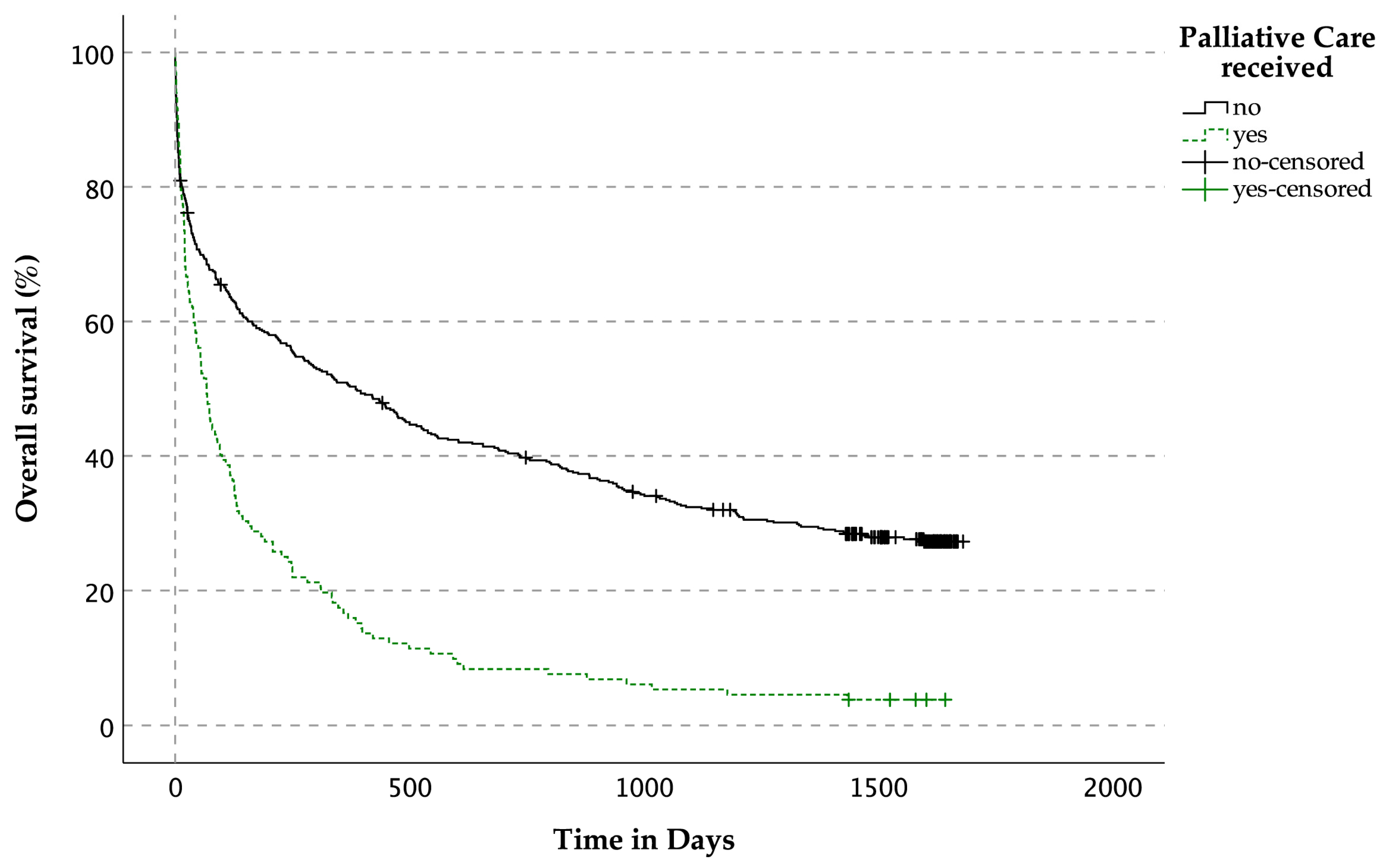

3.3. Overall Survival Analyses

3.3.1. Overall Survival Analysis for Patients with LLDs (n = 631) Related to the Number of LLDs

3.3.2. OS Related to the Prevalence of Unmet Palliative Care Needs for Patients with LLDs

3.3.3. OS Related to the Prevalence of Palliative Care Services for Patients with LLDs

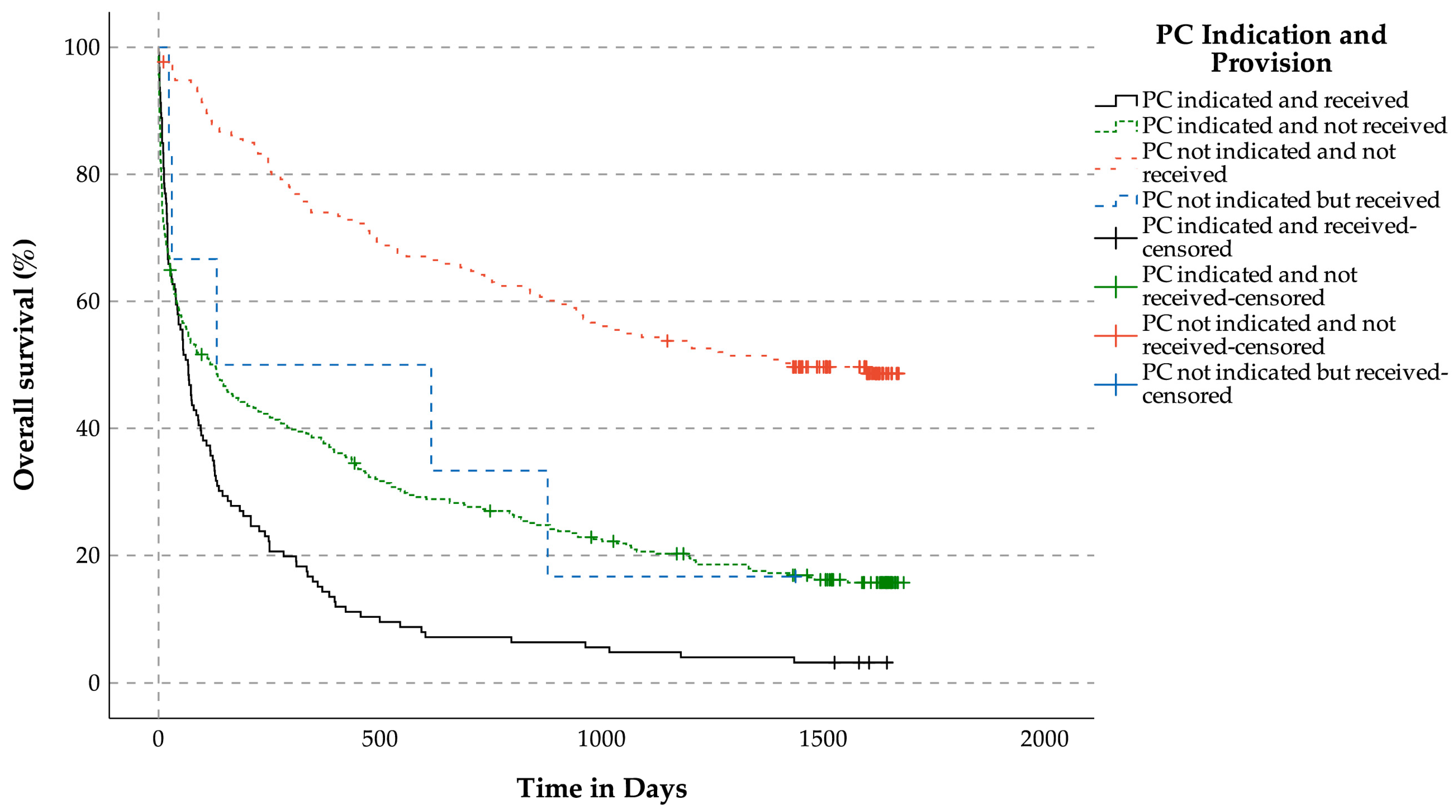

3.3.4. OS Related to Indication for Palliative Care Services and Reception of Palliative Care Services for Patients with LLDs

3.3.5. OS Related to the Surprise Question for Patients with LLDs (Figure 7)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Emergency department |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LLD | Life-limiting disease |

| P-CaRES | Palliative Care and Rapid Emergency Screening |

| PC | Palliative care |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| OS | Overall survival |

| SPICT | Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool |

| SQ | Surprise question |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Maresova, P.; Javanmardi, E.; Barakovic, S.; Barakovic Husic, J.; Tomsone, S.; Krejcar, O.; Kuca, K. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age–a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, J.; Ng, C.W.T.; Teo, K.E.L.; Peh, A.L.T.; Lim, Y.W. Co-designing care for multimorbidity: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhatim, N.A.; AlShehery, M.Z. Exploring the Challenges in Palliative Care As Perceived by the Saudi Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e66579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmeeri, M.; Islam, A.; Banik, P.C. Challenges experienced by health care providers working in both hospital and home-based palliative care units in Dhaka city: A multi-center based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitima, G.; Galhardo-Branco, C.; Reis-Pina, P. Equity of access to palliative care: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D.E.; Meier, D.E. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, S.J.; Nieboer, A.P.; Cramm, J.M. Making care more patient centered; experiences of healthcare professionals and patients with multimorbidity in the primary care setting. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Bansal, S.; Strasser, F.; Morita, T.; Caraceni, A.; Davis, M.; Cherny, N.; Kaasa, S.; Currow, D.; Abernethy, A. Indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care programs: An international consensus. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Henson, L.A.; Maddocks, M.; Evans, C.; Davidson, M.; Hicks, S.; Higginson, I.J. Palliative Care and the Management of Common Distressing Symptoms in Advanced Cancer: Pain, Breathlessness, Nausea and Vomiting, and Fatigue. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; Aapro, M.; Albreht, T.; Anderson, R.; Bruera, E.; Brunelli, C.; Caraceni, A.; Cervantes, A.; Currow, D.C.; et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e588–e653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Heung, Y.; Bruera, E. Timely Palliative Care: Personalizing the Process of Referral. Cancers 2022, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakitas, M.A.; Tosteson, T.D.; Li, Z.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Hegel, M.T. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; LeBlanc, T.; VanDusen, H.; Traeger, L.; Greer, J.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Jackson, V.A.; Telles, J.; Rhodes, A.; Spitzer, T.R. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.J.; Harding, R.; Higginson, I.J. ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: A meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Wu, L.-P.; Wang, H.; Han, Q.; Wang, S.-N.; Zhang, J. The clinical effect evaluation of multidisciplinary collaborative team combined with palliative care model in patients with terminal cancer: A randomised controlled study. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantilat, S.Z.; O’Riordan, D.L.; Dibble, S.L.; Landefeld, C.S. Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 2038–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabow, M.W.; Dibble, S.L.; Pantilat, S.Z.; McPhee, S.J. The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderovich, H.; McFadyen, K. Palliative care: Too good to be true? Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2020, 11, e0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, S.P.; Chui, K.; Koch-Weser, S. Lack of awareness and common misconceptions about palliative care among adults: Insights from a national survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Ding, J.; Jiao, J.; Tang, S.; Huang, C. Screening instruments for early identification of unmet palliative care needs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavabie, S.; Ta, Y.; Stewart, E.; Tavabie, O.; Bowers, S.; White, N.; Seton-Jones, C.; Bass, S.; Taubert, M.; Berglund, A.; et al. Seeking Excellence in End of Life Care UK (SEECare UK): A UK multi-centred service evaluation. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, e1395–e1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, C.; Gott, M.; Ingleton, C.; Seymour, J.; Cobb, M.; Noble, B.; Bennett, M.; Ryan, T. Extent of palliative care need in the acute hospital setting: A survey of two acute hospitals in the UK. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMokhallalati, Y.; Bradley, S.H.; Chapman, E.; Ziegler, L.; Murtagh, F.E.; Johnson, M.J.; Bennett, M.I. Identification of patients with potential palliative care needs: A systematic review of screening tools in primary care. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, N.; Barrett, N.; McPeake, L.; Goett, R.; Anderson, K.; Baird, J. Content Validation of a Novel Screening Tool to Identify Emergency Department Patients With Significant Palliative Care Needs. Acad. Emerg. Med. Off. J. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.; George, N.; Barrett, N.; Anderson, K.; Dove-Maguire, K.; Baird, J. Acceptability and reliability of a novel palliative care screening tool among emergency department providers. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenberger, M.; Neuwersch, S.; Weixler, D.; Pipam, W.; Zink, M.; Likar, R. Prevalence of palliative care patients in emergency departments. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2019, 131, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Durbin, M.; Chung, F.R.; Rubin, A.L.; Cuthel, A.M.; McQuilkin, J.A.; Modrek, A.S.; Jamin, C.; Gavin, N.; Mann, D. Design and implementation of a clinical decision support tool for primary palliative Care for Emergency Medicine (PRIM-ER). BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, S.W.; Garrido Clua, M.; Kruhlak, M.; Villa-Roel, C.; Couperthwaite, S.; Yang, E.H.; Elwi, A.; O’Neill, B.; Duggan, S.; Brisebois, A. Comparison of characteristics and management of emergency department presentations between patients with met and unmet palliative care needs. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, J.; Tewes, M.; Mathew, B.; Bubel, M.; Kill, C.; Risse, J.; Huessler, E.-M.; Kowall, B.; Salvador Comino, M.R. Validation of the Palliative Care and Rapid Emergency Screening (P-CaRES) Tool in Germany. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; Block, S.D.; Schonberg, M.A.; Jamieson, E.S.; Aaronson, E.L.; Pallin, D.J.; Tulsky, J.A.; Schuur, J.D. Feasibility testing of an emergency department screening tool to identify older adults appropriate for palliative care consultation. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.; Crump, S.; O’Connor, E. P034: Identifying unmet palliative care needs in the emergency department. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 21, S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, T.-T.; Tsou, Y.-J.; Lin, M.-H.; Fan, J.-S.; Huang, H.-H.; Tsai, M.-C.; Yen, D.H.-T. Initiating palliative care consultation for acute critically ill patients in the emergency department intensive care unit. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2020, 83, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paske, J.R.T.; DeWitt, S.; Hicks, R.; Semmens, S.; Vaughan, L. Palliative care and rapid emergency screening tool and the palliative performance scale to predict survival of older adults admitted to the hospital from the emergency department. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med.® 2021, 38, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolia, V.; Yourman, L.; Brennan, J.; Cronin, A.; Castillo, E. 182 Initial Evaluation of a Palliative Care Screening Tool in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Martínez-Muñoz, M.; Blay, C.; Amblàs, J.; Vila, L.; Costa, X.; Espaulella, J.; Espinosa, J.; Constante, C.; Mitchell, G.K. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with advanced chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: A cross-sectional study. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Turrillas, P.; Tebé, C.; Calsina-Berna, A.; Amblàs-Novellas, J. NECPAL tool prognostication in advanced chronic illness: A rapid review and expert consensus. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, e10–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, S.P.; Black, P.; McCheyne, L.; Wilson, D.; Penfold, R.S.; Stapleton, L.; Channer, P.; Mills, S.E.; Williams, L.; Quirk, F. Descriptions of advanced multimorbidity: A scoping review with content analysis. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2025, 15, 26335565251326309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakitas, M.; Lyons, K.D.; Hegel, M.T.; Balan, S.; Brokaw, F.C.; Seville, J.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Tosteson, T.D.; Byock, I.R.; et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalieratos, D.; Corbelli, J.; Zhang, D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Hanmer, J.; Hoydich, Z.P.; Ikejiani, D.Z.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2104–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.E.; Bausewein, C.; Verne, J.; Groeneveld, E.I.; Kaloki, Y.E.; Higginson, I.J. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.; Dionne, A.; Potvin, D. Factors associated with length of survival among 1081 terminally ill cancer patients. J. Palliat. Care 1995, 11, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.P.; Vanenkevort, E. The surprise question. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-F.; Lee, Y.-L.; Hu, H.-Y.; Sun, W.-J.; Ko, M.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Wong, W.K.; Morisky, D.E.; Huang, S.-J.; Chu, D. Early palliative care: The surprise question and the palliative care screening tool—Better together. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downar, J.; Goldman, R.; Pinto, R.; Englesakis, M.; Adhikari, N.K. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cmaj 2017, 189, E484–E493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresillassie, B.M.; Attia, J.R.; Mersha, A.G.; Harris, M.L. Prognostic models and factors identifying end-of-life in non-cancer chronic diseases: A systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, e2316–e2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounsey, L.; Ferres, M.; Eastman, P. Palliative care for the patient without cancer. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepgul, N.; Gao, W.; Evans, C.J.; Jackson, D.; van Vliet, L.M.; Byrne, A.; Crosby, V.; Groves, K.E.; Lindsay, F.; Higginson, I.J.; et al. Integrating palliative care into neurology services: What do the professionals say? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehm, A.; Hazeltine, A.M.; Greer, J.A.; Traeger, L.; Nelson-Lowe, M.; Brizzi, K.; Jacobsen, J. Neurology clinicians’ views on palliative care communication: “How do you frame this?”. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2020, 10, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamano, J.; Shima, Y.; Kizawa, Y. Current situation and support need for non-cancer patients’ admission to inpatient hospices/palliative care units in Japan: A nationwide multicenter survey. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüthi, F.T.; MacDonald, I.; Amoussou, J.R.; Bernard, M.; Borasio, G.D.; Ramelet, A.-S. Instruments for the identification of patients in need of palliative care in the hospital setting: A systematic review of measurement properties. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases | Patients with PC Needs | Patients with PC Needs Who Received PC | Patients Who Received PC Without Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 631 (100%) | 451 (71.5%) | 126 (20.0%) | 6 (1.0%) |

| Male | 365 (57.8%) | 262 (58.1%) | 72 (57.1%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Female | 266 (42.2%) | 189 (41.9%) | 54 (42.9%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Neurological disease/dementia | 131 (20.8%) | 109 (24.2%) | 15 (11.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Advanced cancer | 195 (30.9%) | 129 (28.6%) | 75 (59.5%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Hematological malignancy | 51 (8.1%) | 31 (6.9%) | 8 (6.3%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| End-stage renal disease | 21 (3.3%) | 16 (3.5%) | 5 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| End-stage COPD | 88 (13.9%) | 59 (13.1%) | 10 (7.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| End-stage cardiac disease | 70 (11.1%) | 54 (12.0%) | 10 (7.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| End-stage liver disease | 17 (2.7%) | 14 (3.1%) | 5 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Septic shock with signs of organ failure | 28 (4.4%) | 24 (5.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Provider-based identification | 215 (34.1%) | 189 (41.9%) | 36 (28.6%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Frequent visits | 227 (36.0%) | 211 (46.8%) | 67 (53.2%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Uncontrolled symptoms | 504 (79.9%) | 419 (92.9%) | 117 (92.9%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Functional decline | 211 (33.4%) | 207 (45.9%) | 55 (43.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Uncertainty regarding goals of care | 98 (15.5%) | 98 (21.7%) | 24 (19.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Surprise question | 436 (69.1%) | 411 (91.1%) | 122 (96.8%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Consultation by PC team indicated | 451 (71.5%) | 451 (100.0%) | 126 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Patient consulted by PC team | 132 (20.9%) | 126 (27.9%) | 126 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) |

| Age at admission (median) | 78.0 years (IQR 18.0) | 80.0 years (IQR 16.0) | 77.5 years (IQR 16.0) | 71.5 years (IQR 15.2) |

| Length of hospital stay (median) | 6.0 days (IQR 9.0) | 6.0 days (IQR 10.0) | 7.0 days (IQR 12.0) | 2.5 days (IQR 4.0) |

| Number of admissions (median) | 1.0 (IQR 1.0) | 1.0 (IQR 1.0) | 1.0 (IQR 1.0) | 3.0 (IQR 1.5) |

| Diagnoses and Clinical Indicators | Patients with PC Needs | Patients with PC Needs Who Received PC | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological disease/dementia | 109 (24.2%) | 15 (11.9%) | 0.003 |

| Advanced cancer | 129 (28.6%) | 75 (59.5%) | <0.001 |

| Hematological malignancy | 31 (6.9%) | 8 (6.3%) | 0.836 |

| End-stage renal disease | 16 (3.5%) | 5 (4.0%) | 0.824 |

| End-stage COPD | 59 (13.1%) | 10 (7.9%) | 0.116 |

| End-stage cardiac disease | 54 (12.0%) | 10 (7.9%) | 0.202 |

| End-stage liver disease | 14 (3.1%) | 5 (4.0%) | 0.631 |

| Septic shock with signs of organ failure | 24 (5.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 0.167 |

| Provider-based identification | 189 (41.9%) | 36 (28.6%) | 0.007 |

| Frequent visits | 211 (46.8%) | 67 (53.2%) | 0.204 |

| Uncontrolled symptoms | 419 (92.9%) | 117 (92.9%) | 0.985 |

| Functional decline | 207 (45.9%) | 55 (43.7%) | 0.654 |

| Uncertainty regarding goals of care | 98 (21.7%) | 24 (19.0%) | 0.515 |

| Surprise question | 411 (91.1%) | 122 (96.8%) | 0.033 |

| Diagnoses and Clinical Indicators | Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases | Patients with PC Needs | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological disease/dementia | 131 (20.8%) | 109 (24.2%) | 0.209 |

| Advanced cancer | 195 (30.9%) | 129 (28.6%) | 0.455 |

| Hematological malignancy | 51 (8.1%) | 31 (6.9%) | 0.532 |

| End-stage renal disease | 21 (3.3%) | 16 (3.5%) | 0.979 |

| End-stage COPD | 88 (13.9%) | 59 (13.1%) | 0.750 |

| End-stage cardiac disease | 70 (11.1%) | 54 (12.0%) | 0.725 |

| End-stage liver disease | 17 (2.7%) | 14 (3.1%) | 0.830 |

| Septic shock with signs of organ failure | 28 (4.4%) | 24 (5.3%) | 0.599 |

| Provider-based identification | 215 (34.1%) | 189 (41.9%) | 0.010 |

| Frequent visits | 227 (36.0%) | 211 (46.8%) | <0.001 |

| Uncontrolled symptoms | 504 (79.9%) | 419 (92.9%) | <0.001 |

| Functional decline | 211 (33.4%) | 207 (45.9%) | <0.001 |

| Uncertainty regarding goals of care | 98 (15.5%) | 98 (21.7%) | 0.011 |

| Surprise question | 436 (69.1%) | 411 (91.1%) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fidelsberger, L.; Fischer, C.; Kreye, G.; Meran, E.; Likar, R.; van Tulder, R.; Stettner, H.; Masel, E.K.; Singer, J.; Le, N.-S. Using the P-CaRES Tool to Identify Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases: An Analysis of Internal Medicine Admissions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124206

Fidelsberger L, Fischer C, Kreye G, Meran E, Likar R, van Tulder R, Stettner H, Masel EK, Singer J, Le N-S. Using the P-CaRES Tool to Identify Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases: An Analysis of Internal Medicine Admissions. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124206

Chicago/Turabian StyleFidelsberger, Luise, Claudia Fischer, Gudrun Kreye, Eleonora Meran, Rudolf Likar, Raphael van Tulder, Haro Stettner, Eva Katharina Masel, Josef Singer, and Nguyen-Son Le. 2025. "Using the P-CaRES Tool to Identify Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases: An Analysis of Internal Medicine Admissions" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124206

APA StyleFidelsberger, L., Fischer, C., Kreye, G., Meran, E., Likar, R., van Tulder, R., Stettner, H., Masel, E. K., Singer, J., & Le, N.-S. (2025). Using the P-CaRES Tool to Identify Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases: An Analysis of Internal Medicine Admissions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124206