Anxiety, Coping, and Self-Efficacy as a Psychological Adjustment in Mothers Who Have Experienced a Preterm Birth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

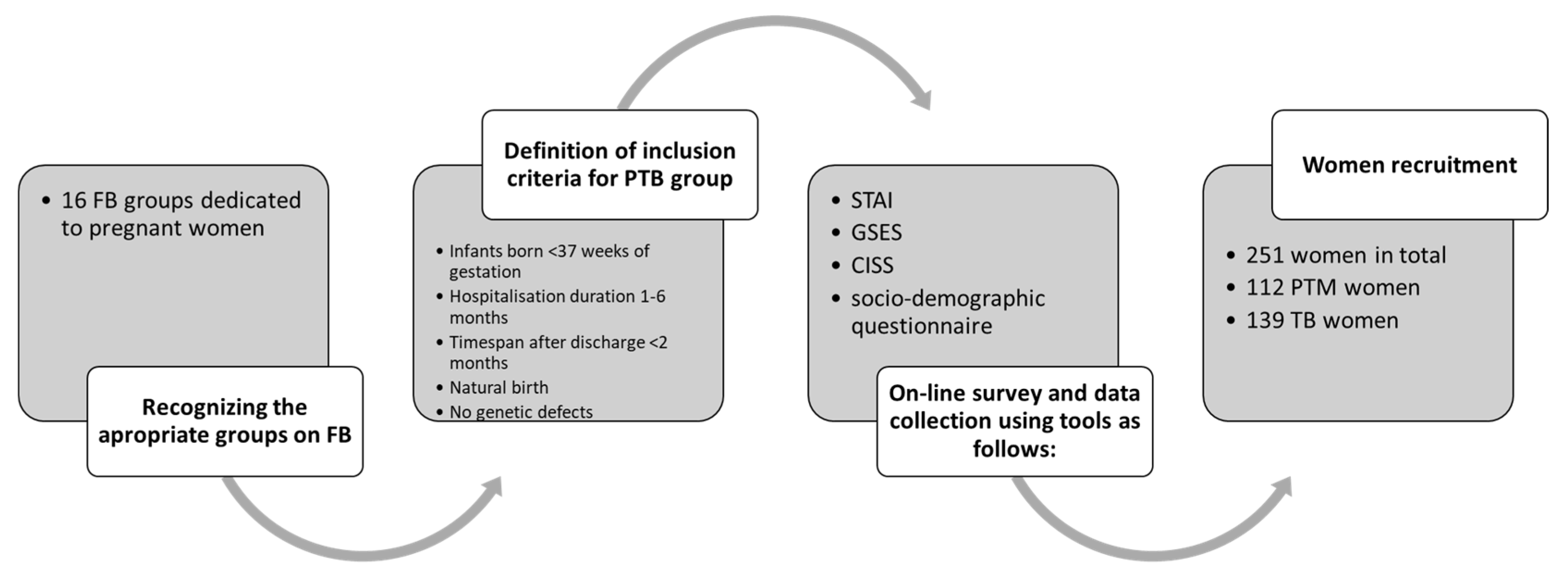

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Methods

2.3. Tools

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. The Analysis of the Questionnaire Data

3.3. Psychological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Chou, D.; Oestergaard, M.; Say, L.; Moller, A.B.; Kinney, M.; Lawn, J.; Born Too Soon Preterm Birth Action Group. Born too soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod. Health 2013, 10 (Suppl. S1), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Vogel, J.P.; Moller, A.B.; Lumbiganon, P.; Petzold, M.; Hogan, D.; Landoulsi, S.; Jampathong, N.; Kongwattanakul, K.; Laopaiboon, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. United Nations Children’s Fund; Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2017; UN Inter: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ohuma, E.O.; Moller, A.B.; Bradley, E.; Chakwera, S.; Hussain-Alkhateeb, L.; Lewin, A.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Mahanani, W.R.; Johansson, E.W.; Lavin, T.; et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2023, 402, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, J.E.; Davidge, R.; Paul, V.K.; von Xylander, S.; de Graft Johnson, J.; Costello, A.; Kinney, M.V.; Segre, J.; Molyneux, L. Born too soon: Care for the preterm baby. Reprod. Health 2013, 10 (Suppl. S1), S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jańczewska, I.; Cichoń-Kotek, M.; Glińska, M.; Deptulska-Hurko, K.; Basiński, K.; Woźniak, M.; Wiergowski, M.; Biziuk, M.; Szablewska, A.; Cichoń, M.; et al. Contributors to Preterm Birth: Data from a Single Polish Perinatal Center. Children 2023, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, C.; Pezzani, M.; Moro, G.E.; Minoli, I. Management of extremely low-birth-weight infants. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 1992, 382, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO: Recommended definitions, terminology and format for statistical tables related to the perinatal period and use of a new certificate for cause of perinatal deaths. Modifications recommended by FIGO as amended October 14, 1976. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1977, 56, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, H.C.; Costarino, A.T.; Stayer, S.A.; Brett, C.M.; Cladis, F.; Davis, P.J. Outcomes for extremely premature infants. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 120, 1337–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirogowicz, I.; Steciwko, A. Noworodek przedwcześnie urodzony—Trudności i satysfakcje. In Dziecko i Jego Środowisko, 1st ed.; Continuo: Wroclaw, Poland, 2008; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- O‘Shea, T.M.; Allred, E.N.; Dammann, O.; Hirtz, D.; Kuban, K.C.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A. The ELGAN study of the brain and related disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns. Early Hum. Dev. 2009, 85, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, B.; Ohrling, K. Experiences of having a prematurely born infant from the perspective of mothers in northern Sweden. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2008, 67, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasiuk, G.C.; Comeau, T.; Newburn-Cook, C. Unexpected: An interpretive description of parental traumas’ associated with preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13 (Suppl. S1), S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaari, M.; Treyvaud, K.J.; Lee, K.; Doyle, L.W.; Anderson, P.J. Preterm Birth and Maternal Mental Health: Longitudinal Trajectories and Predictors. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napiórkowska-Orkisz, M.; Olszewska, J. Wpływ holistycznej opieki nad pacjentem OITN na psychologiczne i fizyczne aspekty wcześniactwa. Pol. Prz. Nauk Zdr. 2017, 1, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczak-Wawrzyniak, J.; Czarnecka, M.; Konofalska, N.; Bukowska, A.; Gadzinowski, J. Holistyczna koncepcja opieki nad wcześniakiem lub (i) dzieckiem chorym—Pacjentem Oddziału Intensywnej Terapii Noworodka i jego rodzicami. Perinatol. Neonatol. Ginekol. 2010, 3, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffenkamp, H.N.; Tooten, A.; Hall, R.A.S.; Croon, M.A.; Braeken, J.; Winkel, F.W.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M.; van Bakel, H.J.A. The Impact of Premature Childbirth on Parental Bonding. Evol. Psychol. 2012, 10, 542–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, K.W.; Holditch-Davis, D. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of preterm infants. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 3, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.; de Groot, V. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease and rehabilitation—An exploration. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, M. Global, Regional, and National Incidence and Mortality of Neonatal Preterm Birth, 1990–2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrhaug, H.T.; Brurberg, K.G.; Hov, L.; Markestad, T. Survival and Impairment of Extremely Premature Infants: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20180933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misund, A.R.; Nerdrum, P.; Diseth, T.H. Mental health in women experiencing preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, S.; Silverio, S.A.; Fallon, V. The Relationship Between Prematurity and Maternal Mental Health in the First Postpartum Year. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 29, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozel, E.; Barnoy, S.; Itzhaki, M. Emotion management of women at risk for premature birth: The association with optimism and social support. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2022, 64, 151568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, C.; Adair, P.; Doherty, N.; McCormack, D. Exploring Adjustment and Parent-Infant Relations in Mothers of Premature Infants: Thematic Analysis Using a Multisensory Approach. J Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 19, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftyka, A.; Rybojad, B.; Rozalska-Walaszek, I.; Rzoñca, P.; Humeniuk, E. Post-traumatic stress disorder in parents of children hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), medical and demographic risk factors. Psychiatr. Danub. 2014, 26, 347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Hynan, M.T.; Mounts, K.O.; Vanderbilt, D.L. Screening parents of high-risk infants for emo-tional distress: Rationale and recommendations. J. Perinatol. 2013, 33, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białas, A.; Nowak, A.; Kamecka, K.; Rasmus, P.; Timler, D.; Marczak, M.; Kozłowski, R.; Lipert, A. Self-Efficacy and Perceived Stress in Women Experiencing Preterm Birth. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; The Laboratory of Psychological Tests of the Polish Psychological Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z. Zachowania zdrowotne i wartościowanie zdrowia. In Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; The Laboratory of Psychological Tests of the Polish Psychological Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2001; pp. 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbkowska, M. Some aspects of anxiety in victims of domestic violence. Psychiatria 2008, 5, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, S.L.; Abdullah, K.L.; Danaee, M.; Soh, K.L.; Soh, K.G.; Japar, S. Stress and anxiety among mothers of premature infants in a Malaysian neonatal intensive care unit. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2019, 37, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokopowicz, A.; Stanczykiewicz, B.; Uchmanowicz, I. Validation of the Numerical Anxiety Rating Scale in postpartum females: A prospective observational study. Ginekol. Pol. 2022, 93, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelau, J.; Jaworowska, A. CISS Kwestionariusz Radzenia Sobie w Sytuacjach Stresowych—Podręcznik, 4th ed.; The Laboratory of Psychological Tests of the Polish Psychological Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stelter, Ż. The ways of coping with stress of mothers of mentally handicapped children. Studia Edukacyjne 2004, 6, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Siudem, A. Styles of coping with stress and personality. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. J. 2009, 21, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Trumello, C.; Candelori, C.; Cofini, M.; Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L.; Paciello, M.; Babore, A. Mothers’ Depression, Anxiety, and Mental Representations After Preterm Birth: A Study During the Infant’s Hospitalization in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepaniak, P.; Strelau, J.; Wrześniewski, K. Kwestionariusz Radzenia Sobie w Sytuacjach Stresowych CISS: Podręcznik do Polskiej Normalizacji; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.M.; Rachubińska, K.; Stanisławska, M.; Grochans, S.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A.; Grochans, E. Analysis of Factors Related to Mental Health, Suppression of Emotions, and Personality Influencing Coping with Stress among Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Wang, D.; Ding, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X. Mediation role of telomere length in the relationship between physical activity and PhenoAge: A population-based study. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2025, 23, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Ding, H.; Tang, M.; Wang, W.; Yan, N.; Min, L.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X. Dose-response relationship between leisure-time physical activity and metabolic syndrome in short sleep US adults: Evidence from a nationwide investigation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maternal depression and child development. Paediatr. Child Health 2004, 9, 575–598. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.; Green, J.; Elliott, D.; Petty, J.; Whiting, L. The forgotten mothers of extremely preterm babies: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2124–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive summary: Neonatal encephalopathy and neurologic outcome, second edition. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 896–901. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomska, I.; Bień, A.; Rzońca, E.; Jurek, K. The Mediating Role of Dispositional Optimism in the Relationship between Health Locus of Control and Self-Efficacy in Pregnant Women at Risk of Preterm Delivery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaria, Q.; Mokh, A.A. Coping with Stress During the Coronavirus Outbreak: The Contribution of Big Five Personality Traits and Social Support. Int. J. Ment Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1854–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Ramezani, M.; Vaghee, S.; Sadeghi, T. The Effect of Applying Problem-solving Skills on Stress Coping Styles and Emotional Self-efficacy in Mothers of Preterm Neonates: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2024, 12, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J.; Kim, J.I. Moderating Effect of General Self-Efficacy on the Relationship between Pregnancy Stress, Daily Hassles Stress, and Preterm Birth Risk in Women Experiencing Pre-term Labor: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2024, 54, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, R.; Hein, E.; Nellis, P.; Smith, J.; McGrath, J.M.; Collins, M.; Barker, A. The Baby Bridge program: A sustainable program that can improve therapy service delivery for preterm infants following NICU discharge. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, B.S.; Lewis, L.E.; Margaret, B.; Bhat, Y.R.; D’Almeida, J.; Phagdol, T. Randomized controlled trial on effectiveness of mHealth (mobile/smartphone) based Preterm Home Care Program on developmental outcomes of preterms: Study protocol. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W. Concept Analysis of Family-Centered Care of Hospitalized Pediatric Patients. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 42, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukari, A.S.; Schmollgruber, S. Concepts of family-centered care at the neonatal and paediatric intensive care unit: A scoping review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 71, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmus, P.; Kozłowska, E.; Robaczyńska, K.; Pękala, K.; Timler, D.; Lipert, A. Evaluation of emergency medical services staff knowledge in breaking bad news to patients. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060520918699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.L.; Cross, J.; Selix, N.W.; Patterson, C.; Segre, L.; Chuffo-Siewert, R.; Geller, P.A.; Martin, M.L. Recommendations for enhancing psychosocial support of NICU parents through staff education and support. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35 (Suppl. S1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogala, D.; Ossowski, R. The efficiency awareness level of pregnant women and selected aspects of the course of childbirth. Pielęg. Pol. 2017, 3, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fabbri, A.; De Iaco, F.; Marchesini, G.; Pugliese, F.R.; Giuffrida, C.; Guarino, M.; Fera, G.; Riccardi, A.; Manca, S. Società Italiana di Emergenza Urgenza (SIMEU) Study Center and Research Group. The coping styles to stress of Italian emergency health-care professionals after the first peak of COVID 19 pandemic outbreak. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 45, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | PTB Group (N = 112) | T-B Group (N = 139) | p Value | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | 0.36 | |||

| Age | 35.0 (8.50) | 37.0 (11.00) | 0.008 | |

| Work experience | 11.0 (8.00) | 13.0 (10.00) | 0.010 | 0.36 |

| Apgar score | 7.0 (3.00) | 10.0 (1.00) | 0.0001 | 1.45 |

| N (%) | ||||

| Siblings | ||||

| Yes | 53 (47.3) | 67 (48.2) | 0.023 | - |

| No | 59 (52.7) | 72 (51.8) | 0.030 | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unmarried | 18 (16.1) | 10 (7.2) | 0.066 | - |

| Married | 85 (75.9) | 114 (82.0) | 0.0001 | - |

| Divorced | 9 (8.0) | 13 (9.3) | 0.318 | - |

| Separated | 0 | 2 (1.4) | 0.132 | - |

| Place of residence | ||||

| City over 50,000 citizens | 55 (49.1) | 67 (48.2) | 0.051 | - |

| City below 50,000 citizens | 25 (22.3) | 31 (22.3) | 0.294 | - |

| Village | 31 (27.7) | 38 (27.3) | 0.247 | - |

| No answer | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.1) | 0.273 | - |

| Education | ||||

| National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 1.000 | - |

| Secondary | 19 (16.9) | 15 (10.8) | 0.399 | - |

| Higher | 92 (82.1) | 123 (88.5) | 0.0001 | - |

| Physical health self-assessment | ||||

| Very good | 16 (14.3) | 29 (20.9) | 0.015 | - |

| Good | 50 (44.6) | 73 (52.5) | 0.0002 | - |

| Average | 40 (35.7) | 29 (20.9) | 0.067 | - |

| Bad | 4 (3.6) | 6 (4.3) | 0.474 | - |

| Very bad | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0.237 | - |

| No answer | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | 0.524 | - |

| Mental health self-assessment | ||||

| Very good | 15 (13.4) | 15 (18.0) | 1.000 | - |

| Good | 53 (47.3) | 68 (49.0) | 0.015 | - |

| Average | 31 (27.7) | 28 (20 1) | 0.604 | - |

| Bad | 12 (10.7) | 15 (10.8) | 0.491 | - |

| Very bad | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | 0.524 | - |

| No answer | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.289 | - |

| PTB Group (N = 112) | T-B Group (N = 139) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | |||

| Family support | |||

| Yes | 34 (30.3) | 48 (34.5) | 0.025 |

| Rather yes | 44 (39.3) | 50 (36.0) | 0.344 |

| Hard to say | 16 (14.3) | 22 (15.8) | 0.231 |

| Rather no | 11 (0.9) | 13 (9.3) | 0.629 |

| No | 7 (6.2) | 5 (3.6) | 0.504 |

| No answer | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.289 |

| Presumptions of premature termination | |||

| Yes | 63 (56.2) | 42 (30.2) | 0.001 |

| Don’t know | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.287 |

| No | 49 (43.7) | 95 (68.3) | 0.0001 |

| No answer | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.287 |

| Psychological support in the hospital | |||

| Very often | 5 (4.5) | 1 (0.7) | 0.055 |

| Often | 12 (10.7) | 3 (2.1) | 0.005 |

| Rarely | 22 (19.6) | 10 (7.2) | 0.009 |

| Not at all | 73 (65.2) | 119 (85.6) | 0.0001 |

| No answer | 0 | 6 (4.3) | 0.008 |

| Psychiatric consultation in the hospital | |||

| Yes | 2 (1.8) | 0 | 0.132 |

| No | 110 (98.2) | 132 (95.0) | 0.597 |

| No answer | 0 | 7 (5.0) | 0.004 |

| Information on infant’s health status provided by medical staff | |||

| Sufficient | 68 (60.7) | 91 (65.5) | 0.0001 |

| Medium | 33 (29.5) | 28 (20.1) | 0.391 |

| Insufficient | 11 (9.8) | 19 (13.7) | 0.081 |

| No answer | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.287 |

| Less time for newborns to spend together with their siblings | |||

| Yes | 23 (20.5) | 15 (10.8) | 0.105 |

| Probably yes | 17 (15.2) | 19 (13.7) | 0.682 |

| Not really | 10 (8.9) | 24 (17.3) | 0.004 |

| No | 15 (13.4) | 22 (15.8) | 0.159 |

| No answer | 47 (42.0) | 59 (42.4) | 0.058 |

| The newborn’s siblings felt the need to talk about their feelings and fears | |||

| Yes | 13 (11.6) | 22 (15.8) | 0.065 |

| Probably yes | 6 (5.3) | 16 (11.5) | 0.014 |

| Not really | 17 (15.2) | 17 12.2) | 1.000 |

| No | 14 (12.5) | 16 (11.5) | 0.660 |

| No answer | 62 (55.3) | 68 (48.9) | 0.321 |

| PTB Group (n = 112) | T-B Group (N = 139) | p Value | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | ||||

| GSES | 28.00 (6.00) | 29.00 (5.00) | 0.010 | 0.29 |

| CISS T | 57.50 (16.50) | 59.00 (12.00) | 0.066 | 0.26 |

| CISS E | 4.00 (2.00) | 42.00 (21.00) | 0.0001 | 3.75 |

| CISS A | 37.00 (12.00) | 37.00 (12.00) | 0.710 | 0.04 |

| CISS A-D | 16.00 (7.00) | 16.00 (8.00) | 0.653 | 0.07 |

| CISS A-SD | 14.00 (5.00) | 15.00 (6.00) | 0.225 | 0.14 |

| STAI | 91.50 (36.00) | 87.00 (33.00) | 0.127 | 0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Białas, A.; Kamecka, K.; Rasmus, P.; Timler, D.; Kozłowski, R.; Lipert, A. Anxiety, Coping, and Self-Efficacy as a Psychological Adjustment in Mothers Who Have Experienced a Preterm Birth. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124174

Białas A, Kamecka K, Rasmus P, Timler D, Kozłowski R, Lipert A. Anxiety, Coping, and Self-Efficacy as a Psychological Adjustment in Mothers Who Have Experienced a Preterm Birth. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124174

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiałas, Agata, Karolina Kamecka, Paweł Rasmus, Dariusz Timler, Remigiusz Kozłowski, and Anna Lipert. 2025. "Anxiety, Coping, and Self-Efficacy as a Psychological Adjustment in Mothers Who Have Experienced a Preterm Birth" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124174

APA StyleBiałas, A., Kamecka, K., Rasmus, P., Timler, D., Kozłowski, R., & Lipert, A. (2025). Anxiety, Coping, and Self-Efficacy as a Psychological Adjustment in Mothers Who Have Experienced a Preterm Birth. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124174