Burnout or Depression? Investigating Conceptual and Empirical Distinctions in a High-Stress Occupational Group

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Conceptualization of Job Burnout

1.2. Conceptualization of (Clinical) Depression

1.3. Distinction Between or Overlap of Job Burnout and Depression? Theoretical Debate

1.4. Distinction Between or Overlap of Job Burnout and Depression? A Review of the Evidence

1.5. Occupational Stress and Its Consequences (Including Burnout and Depression) in Police Officers

1.6. Contribution of the Presented Study

2. Method

2.1. Instruments

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

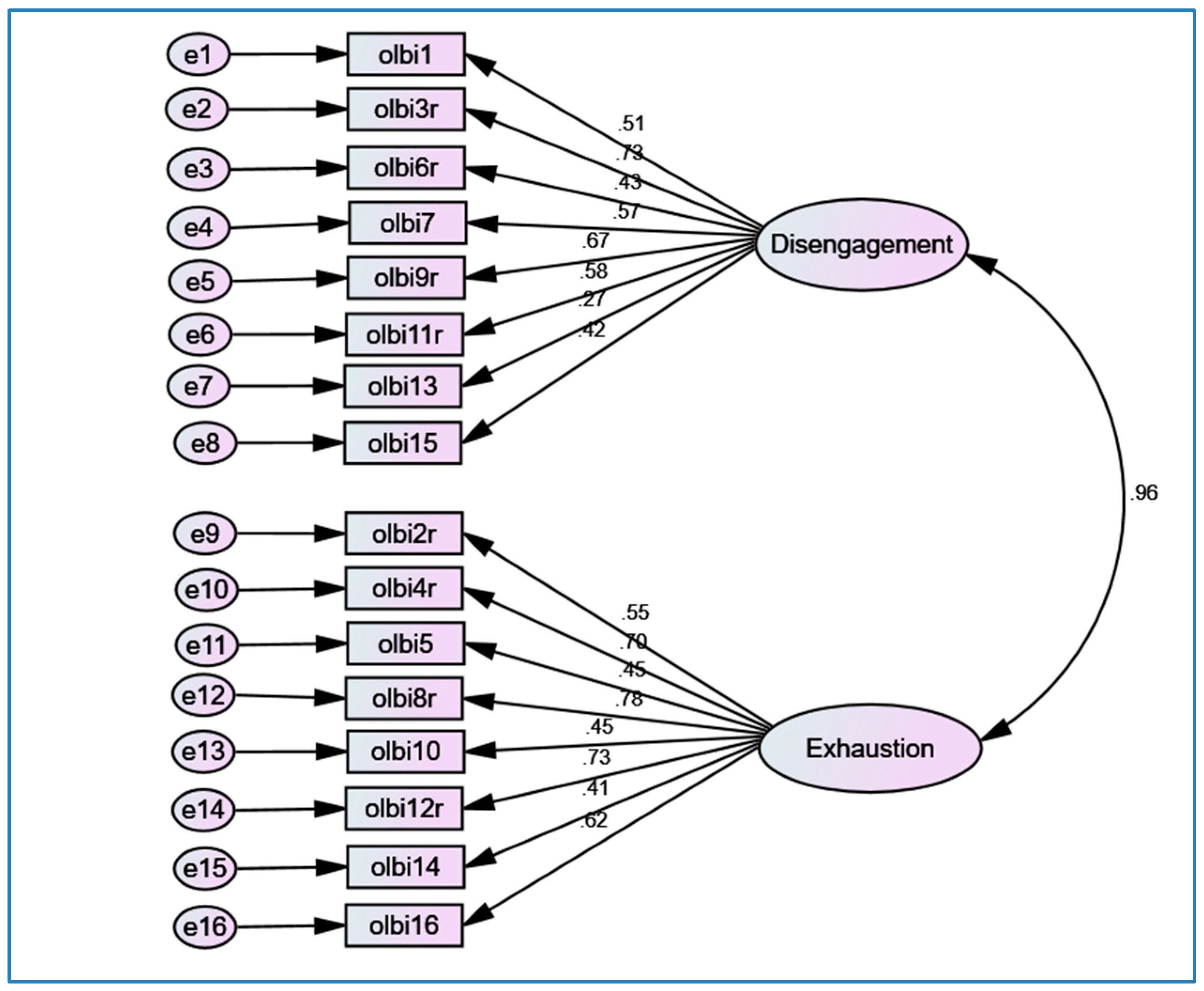

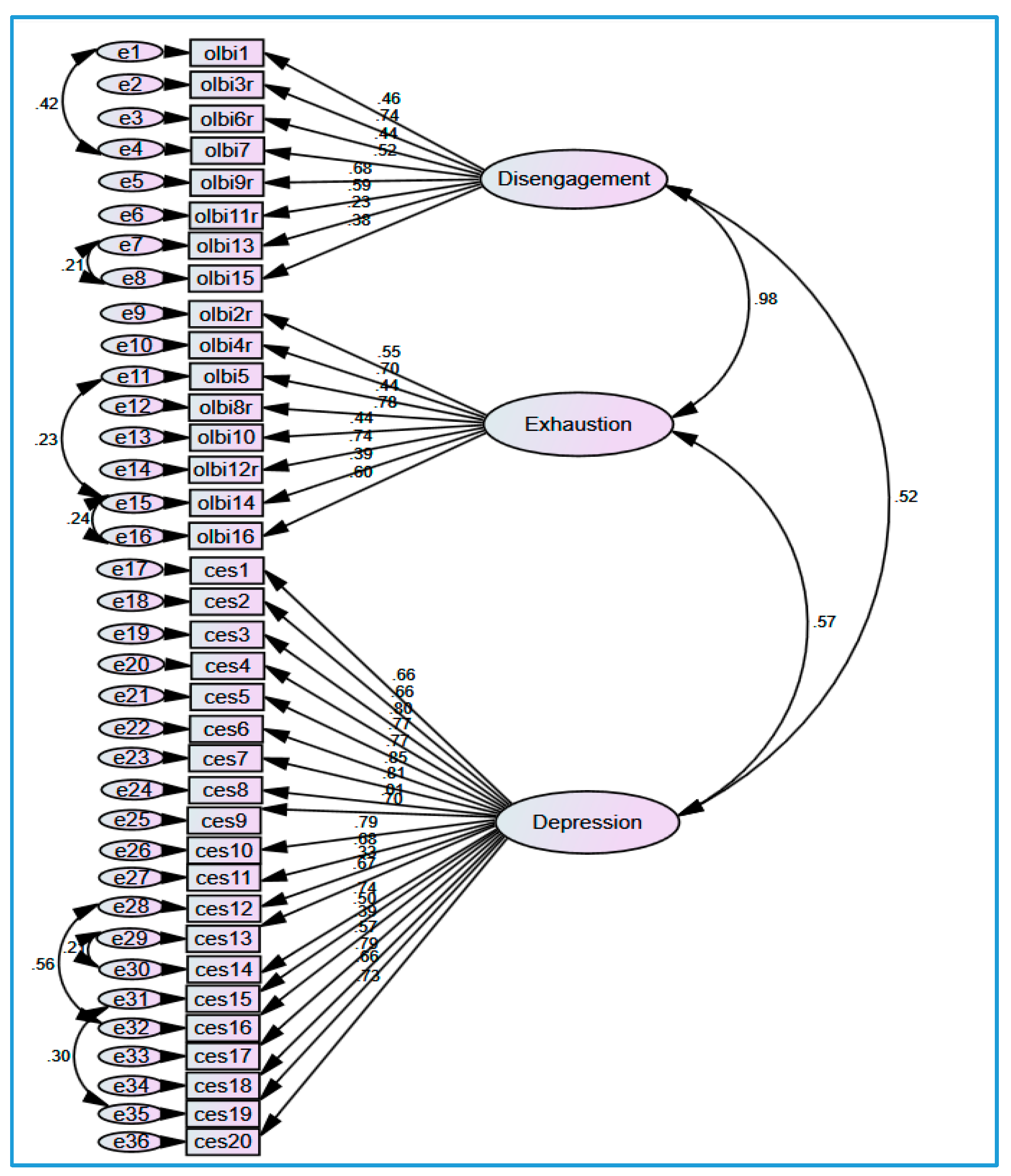

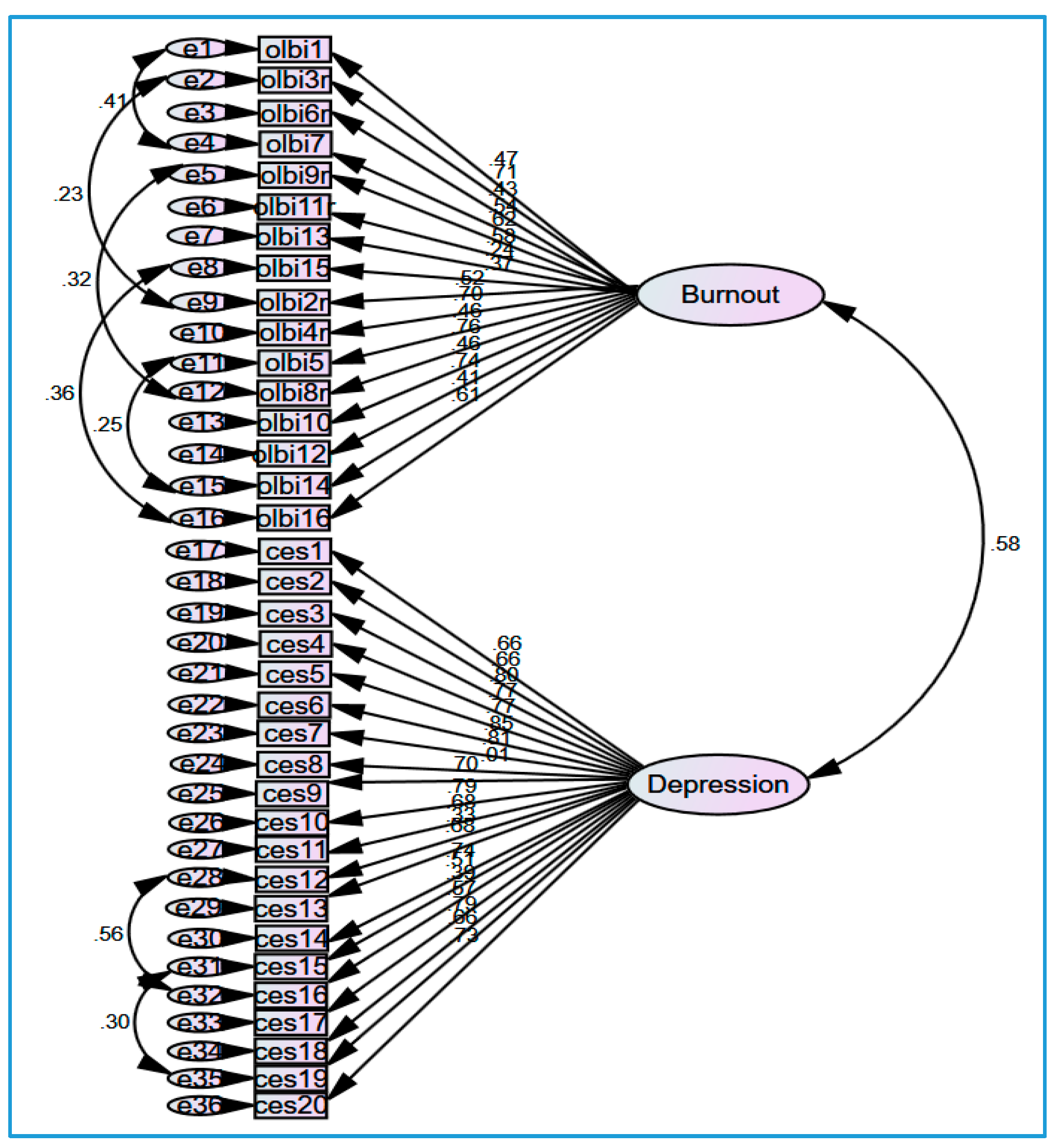

3.1. The Factorial Validity of Burnout and Depression

3.2. Internal Validity of Burnout and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Factor 1: Reversed items 3 (α = 0.86) | ||

| OLBI8r | 0.81 | 0.00 |

| OLBI4r | 0.78 | −0.07 |

| OLBI3r | 0.74 | 0.03 |

| OLBI12r | 0.70 | 0.06 |

| OLBI9r | 0.69 | 0.00 |

| OLBI2r | 0.66 | −0.11 |

| OLBI11r | 0.51 | 0.10 |

| OLBI6r | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| Factor 2: Non-reversed items (α = 0.80) | ||

| OLBI16 | 0.10 | 0.69 |

| OLBI7 | 0.04 | 0.69 |

| OLBI1 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

| OLBI15 | −0.08 | 0.64 |

| OLBI14 | −0.04 | 0.58 |

| OLBI5 | 0.03 | 0.53 |

| OLBI13 | −0.07 | 0.42 |

| OLBI10 | 0.13 | 0.41 |

| % of variance | 32.64% | 7.97% |

References

- Hillert, A.; Albrecht, A.; Voderholzer, U. The Burnout Phenomenon: A Résumé After More Than 15,000 Scientific Publications. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 519237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suls, J.; Bunde, J. Anger, Anxiety, and Depression as Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: The Problems and Implications of Overlapping Affective Dispositions. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 260–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, S.; Shirom, A.; Toker, S.; Berliner, S.; Shapira, I. Burnout and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence, Possible Causal Paths, and Promising Research Directions. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Enzmann, D. The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice: A Critical Analysis; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-7484-0697-5. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberger, H. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burisch, M. In Search of Theory: Some Ruminations on the Nature and Etiology of Burnout. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Series in Applied Psychology: Social Issues and Questions; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 75–93. ISBN 978-1-56032-262-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Sowden, J.F. Five Decades of Debate on Burnout. Med. J. Aust. 2024, 221, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.T.; Kim, S. Meta-Regression Analyses of Relationships between Burnout and Depression with Sampling and Measurement Methodological Moderators. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Hakanen, J.; Perhoniemi, R.; Mutanen, P. Relationship between Burnout and Depressive Symptoms: A Study Using the Person-Centred Approach. Burn. Res. 2014, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Burnout-Depression Overlap: A Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 36, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, S.; Biron, M. Job Burnout and Depression: Unraveling Their Temporal Relationship and Considering the Role of Physical Activity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniss, C. Staff Burnout. Job Stress in the Human Services; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Pines, A.; Kafry, D. The Experience of Tedium in Three Generations of Professional Women. Sex. Roles 1981, 7, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory—ES Form 1981; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluja, A.; Blanch, A.; Garcia, L. Dimensionality of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in School Teachers: A Study of Several Proposals. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, C.L.; Dougherty, T.W. A Review and an Integration of Research on Job Burnout. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates of the Three Dimensions of Job Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. Burnout as a Developmental Process: Consideration of Models. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Series in Applied Psychology: Social Issues and Questions; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 237–250. ISBN 978-1-56032-262-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Evolution and Depression: Issues and Implications. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzagalli, D.A. Depression, Stress, and Anhedonia: Toward a Synthesis and Integrated Model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Malard, L.; Chastang, J.-F. Occupational Factors and Subsequent Major Depressive and Generalized Anxiety Disorders in the Prospective French National SIP Study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Work Stress as a Risk Factor for Major Depressive Episode(s). Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources Theory: Its Implication for Stress, Health, and Resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford Library of Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 127–147. ISBN 978-0-19-537534-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Is It Time to Consider the “Burnout Syndrome” A Distinct Illness? Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintsa, T.; Elovainio, M.; Jokela, M.; Ahola, K.; Virtanen, M.; Pirkola, S. Is There an Independent Association between Burnout and Increased Allostatic Load? Testing the Contribution of Psychological Distress and Depression. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Bianchi, R. Burnout and Depression: Two Entities or One? J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurm, W.; Vogel, K.; Holl, A.; Ebner, C.; Bayer, D.; Mörkl, S.; Szilagyi, I.-S.; Hotter, E.; Kapfhammer, H.-P.; Hofmann, P. Depression-Burnout Overlap in Physicians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Mayor, E.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Burnout-Depression Overlap: A Study of New Zealand Schoolteachers. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2016, 45, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. The Truth About Burnout. In How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do About It; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Bianchi, R. From Burnout to Occupational Depression: Recent Developments in Research on Job-Related Distress and Occupational Health. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 796401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovides, A.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Kaprinis, S.; Kaprinis, G. The Relationship between Job Stress, Burnout and Clinical Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 75, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Demerouti, E.; Janssen, P.P.M.; Hulst, R.V.D.; Brouwer, J. Using Equity Theory to Examine the Difference Between Burnout and Depression. Anxiety Stress Coping 2000, 13, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 326–335. ISBN 978-0-19-852158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M. Burnout, Boredom and Engagement in the Workplace. In An Introduction to Contemporary Work Psychology; Taris, T.W., Peeters, M.C.W., de Jonge, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 291–320. ISBN 978-1-394-25956-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pines, A.M.; Keinan, G. Stress and Burnout: The Significant Difference. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 39, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources Model: A Three-Year Cross-Lagged Study of Burnout, Depression, Commitment, and Work Engagement. Work Stress 2008, 22, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, K.L.; Theriault, J.E.; Stewart, J.G.; Bagby, R.M. Acute and Chronic Stress Exposure Predicts 1-Year Recurrence in Adult Outpatients with Residual Depression Symptoms Following Response to Treatment. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, T.; Mishima, K.; Kitamura, S.; Enomoto, M.; Nagase, Y.; Li, L.; Kaneita, Y.; Ohida, T.; Nishikawa, T.; Uchiyama, M. Relationship between Late-Life Depression and Life Stressors: Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study of a Representative Sample of the Japanese General Population. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 64, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, R.; Verkuilen, J.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Hakanen, J.J.; Jansson-Fröjmark, M.; Manzano-García, G.; Laurent, E.; Meier, L.L. Is Burnout a Depressive Condition? A 14-Sample Meta-Analytic and Bifactor Analytic Study. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 9, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Meier, S.T. Burnout and Depression in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 124, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third Edition. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources; Zalaquett, C.P., Wood, R.J., Eds.; Scarecrow Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 191–218. ISBN 978-0-8108-3231-2. [Google Scholar]

- Glandorf, H.L.; Madigan, D.J.; Kavanagh, O.; Mallinson-Howard, S.H. Mental and Physical Health Outcomes of Burnout in Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Rev. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 0, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.; Hore, K.; Power, J.; Jackson, T. The Relationship between Physician Burnout and Depression, Anxiety, Suicidality and Substance Abuse: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1133484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Fragkou, D.; Katsoulas, T.A. Risk Factors for Stress among Police Officers: A Systematic Literature Review. WORK A J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2021, 68, 1255–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, R.Y.; Fauzi, H.B. Factors Affecting the Work Stress of Police Officers: A Systematic Review. Psycho Idea 2020, 18, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, H.; Tavakoli, H.R.; Rahimi, M.H.; Mohammadi, M. Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence among Armed Forces Personnel (Military Personnel and Police Officers): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.; João, G.S.; Melo, G.; Loureiro, P.; Santos, E. Depression in police officers: A systematic review of prevalence. Millenium—J. Educ. Technol. Health 2025, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, C.; Passos, F.; Bártolo, A.; Marques, A.J.; da Silva, C.F.; Pereira, A. Burnout and Stress Measurement in Police Officers: Literature Review and a Study with the Operational Police Stress Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.; Ashwick, R.; Schlosser, M.; Jones, R.; Rowe, S.; Billings, J. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors for Mental Health Problems in Police Personnel: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Jiang, D.; Qu, Y.; Xu, X. Work Pressure, Coping Styles and Occupational Burnout among Chinese Police Officers: A Meta-Analytic Review. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santre, S. Mental Disorders and Mental Health Promotion in Police Officers. Health Psychol. Res. 2024, 12, 93904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, L.E.; Idemudia, E.S. Burnout and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders in Police Officers: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytwinski, N.K.; Scur, M.D.; Feeny, N.C.; Youngstrom, E.A. The Co-Occurrence of Major Depressive Disorder among Individuals with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikoulas, G.; Charila, D.; Elias, T. The Protective Role of Self-Esteem on Burnout and Depression Symptoms among Police Officers: A Path Analysis Approach. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 2022, 24, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Honkonen, T.; Isometsä, E.; Kalimo, R.; Nykyri, E.; Koskinen, S.; Aromaa, A.; Lönnqvist, J. Burnout in the General Population. Results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfuqaha, O.A.; Alshra’ah, H.S. Burnout among Nurses and Teachers in Jordan: A Comparative Study. Arch. Psych. Psych. 2018, 20, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Hachesu, V.; Naderyan Fe’li, S.; Maajani, K.; Golbabaei, F. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia among Healthcare Workers during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Occup. Health Epidemiol. 2022, 11, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Burback, L.; Wei, Y. Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression among Teachers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maske, U.E.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Seiffert, I.; Jacobi, F.; Hapke, U. Prevalence and Comorbidity of Self-Reported Diagnosis of Burnout Syndrome in the General Population—Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Psychiatr. Prax. 2016, 43, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salk, R.H.; Hyde, J.S.; Abramson, L.Y. Gender Differences in Depression in Representative National Samples: Meta-Analyses of Diagnoses and Symptoms. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 783–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. Burnout: Eine Folge Konkreter Arbeitsbedingungen bei Dienstleistungs- und Produktionstätigkeiten [Burnout: A Consequence of Specific Working Conditions Among Human Service and Production Tasks]; Lang: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baka, Ł.; Basińska, B.A. Psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI). Med. Pr. Work. Health Saf. 2016, 67, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Vardakou, I.; Kantas, A. The Convergent Validity of Two Burnout Instruments: A Multitrait-Multimethod Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, K.S. Morningness-Eveningness and Depressive Symptoms: Test on the Components Level with CES-D in Polish Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A.; Moore, M.T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 361–379. ISBN 978-1-60623-077-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R.J. Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Where, Pray Tell, Did They Get This Idea? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Stage, F.K.; King, J.; Nora, A.; Barlow, E.A. Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. SEM: Measuring Model Fit. Available online: https://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- van Sonderen, E.; Sanderman, R.; Coyne, J.C. Ineffectiveness of Reverse Wording of Questionnaire Items: Let’s Learn from Cows in the Rain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, K.N.; O’Brien, K.E.; Beehr, T.A.; Glazer, S. A Construct of Its Own: Examining the Overlap of Burnout with Depression, Anxiety, and Fatigue. Occup. Health Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiratipaisarl, W.; Surawattanasakul, V.; Sirikul, W. Individual and Organizational Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E.; Glandorf, H.L. Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 931–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricuţoiu, L.P.; Sava, F.A.; Butta, O. The Effectiveness of Controlled Interventions on Employees’ Burnout: A Meta-analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, P.; Hou, Y.; Guo, J.; Lin, C. The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Alleviating Academic Burnout in Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | N | Min | Max | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Burnout—general | 9705 | 8.00 | 64.00 | 40.17 | 8.94 | - | 0.93 *** | 0.94 *** | 0.56 *** |

| 2. Burnout—Disengagement | 9705 | 2.00 | 32.00 | 19.86 | 4.69 | 0.93 *** | - | 0.74 *** | 0.47 *** |

| 3. Burnout—Exhaustion | 9705 | 4.00 | 32.00 | 20.31 | 4.91 | 0.94 *** | 0.74 *** | - | 0.56 *** |

| 4. Depression | 9698 | 0.00 | 60.00 | 14.59 | 11.38 | 0.56 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.56 *** | - |

| Models | Χ2 | df | P | Χ2/df | RMSEA | PCLOSE | SRMR | IFI | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model—“Burnout”—two-factorial | |||||||||

| Model—“Burnout”— Simple CFA | 12,379.19 | 103 | <0.001 | 120.19 | 0.11 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 12,477.19 |

| Model—“Burnout”— CFA with modification indices | 7001.07 | 93 | <0.001 | 75.28 | 0.09 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.87 | 7119.07 |

| Model—“Burnout”—one-factorial | |||||||||

| Model—“Burnout”— Simple CFA | 12,485.36 | 104 | <0.001 | 120.05 | 0.11 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 12,581.53 |

| Model—“Burnout”— CFA with modification indices | 4243.00 | 86 | <0.001 | 49.34 | 0.07 | 0.000 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 4375.00 |

| Model—“Depression” | |||||||||

| Model—“Depression”— Simple CFA | 13,514.71 | 170 | <0.001 | 79.50 | 0.09 | 0.000 | 0.06 | 0.88 | 13,634.71 |

| Model—“Depression”— CFA with modification indices | 5663.03 | 161 | <0.001 | 35.17 | 0.06 | 0.000 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 5801.03 |

| Models | Χ2 | df | P | Χ2/df | RMSEA | PCLOSE | SRMR | IFI | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Model 1—Simple CFA | 52,365.66 | 594 | <0.001 | 88.16 | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.10 | 0.70 | 52,581.66 |

| Model 1— CFA with modification indices | 34,507.65 | 586 | <0.001 | 58.89 | 0.08 | 0.000 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 34,739.65 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Model 2—Simple CFA | 29,460.04 | 591 | <0.001 | 49.85 | 0.07 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 29,682.04 |

| Model 2— CFA with modification indices | 21,315.71 | 584 | <0.001 | 36.50 | 0.06 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.88 | 21,551.71 |

| Model 3 | |||||||||

| Model 3—Simple CFA | 29,638.35 | 593 | <0.001 | 49.98 | 0.07 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 29,856.35 |

| Model 3— CFA with modification indices | 20,218.46 | 586 | <0.001 | 34.50 | 0.06 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 20,450.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baka, Ł.; Prusik, M.; Grala, K. Burnout or Depression? Investigating Conceptual and Empirical Distinctions in a High-Stress Occupational Group. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124036

Baka Ł, Prusik M, Grala K. Burnout or Depression? Investigating Conceptual and Empirical Distinctions in a High-Stress Occupational Group. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124036

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaka, Łukasz, Monika Prusik, and Krzysztof Grala. 2025. "Burnout or Depression? Investigating Conceptual and Empirical Distinctions in a High-Stress Occupational Group" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124036

APA StyleBaka, Ł., Prusik, M., & Grala, K. (2025). Burnout or Depression? Investigating Conceptual and Empirical Distinctions in a High-Stress Occupational Group. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124036