History of an Insidious Case of Metastatic Insulinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

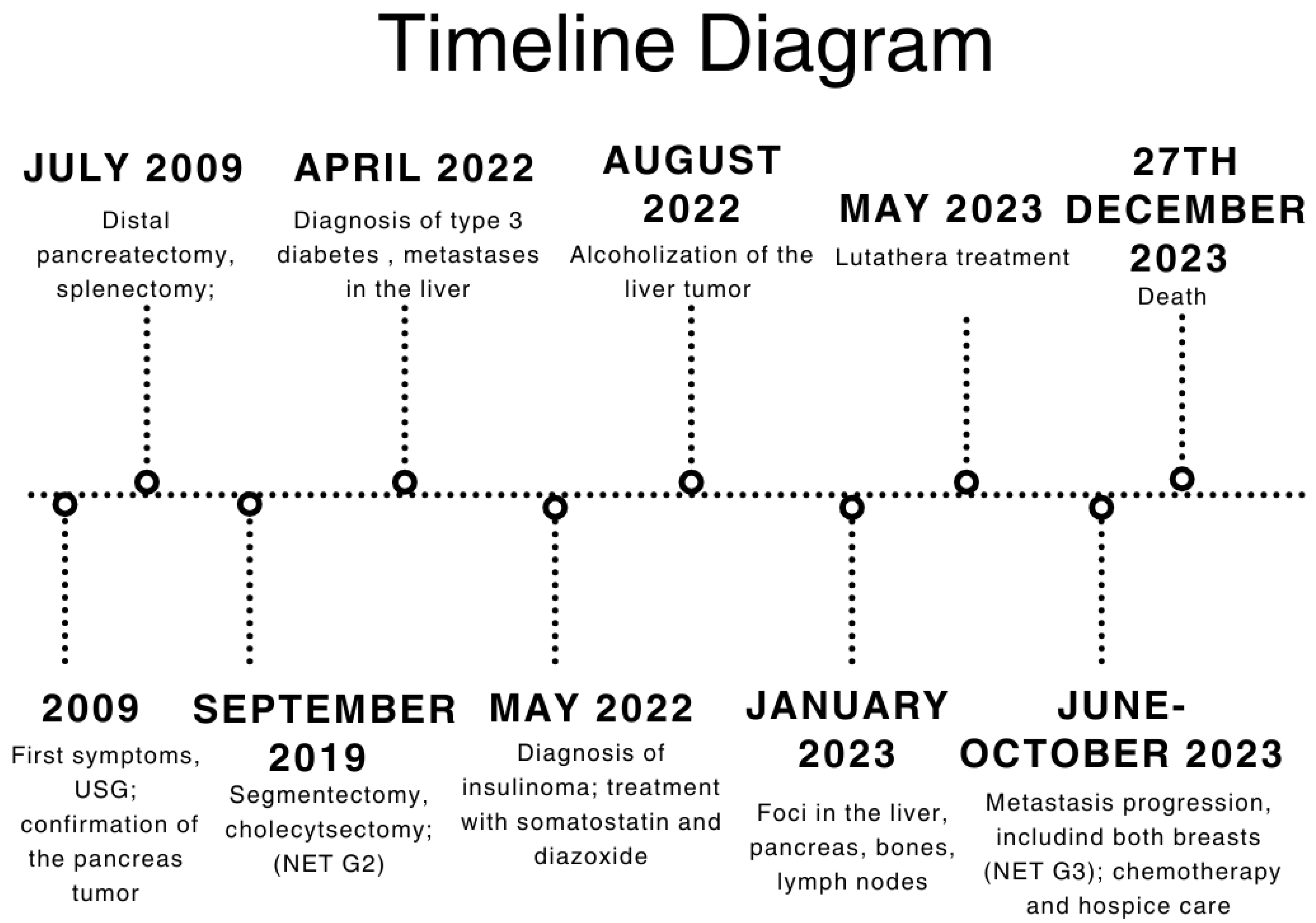

2. Case Description

3. Timeline

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofland, J.; Falconi, M.; Christ, E.; Castaño, J.P.; Faggiano, A.; Lamarca, A.; Perren, A.; Petrucci, S.; Prasad, V.; Ruszniewski, P.; et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society 2023 Guidance Paper for Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumour Syndromes. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 35, e13318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, A.; Glasgow, A.E.; Vella, A.; Thompson, G.B.; McKenzie, T.J.; Habermann, E.B. Malignant Insulinoma: A Rare Form of Neuroendocrine Tumor. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, I.; Mollica, V.; Brighi, N.; Lamberti, G.; Manuzzi, L.; Ricci, A.D.; Campana, D. The Functioning Side of the Pancreas: A Review on Insulinomas. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 43, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Herder, W.W. Insulinoma. Neuroendocrinology 2004, 80, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.J.; Gorden, P.; Libutti, S.K. Insulinoma: Pathophysiology, Localization and Management. Future Oncol. 2010, 6, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, A.; Fischer, L.; Hafezi, M.; Dirlewanger, A.; Grenacher, L.; Diener, M.K.; Fonouni, H.; Golriz, M.; Garoussi, C.; Fard, N.; et al. A Systematic Review of Localization, Surgical Treatment Options, and Outcome of Insulinoma. Pancreas 2014, 43, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.W.; Bennett, J.J. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okabayashi, T.; Shima, Y.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Kozuki, A.; Ito, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Hanazaki, K. Diagnosis and Management of Insulinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, M.; García Sanz, I.; Delgado Valdueza, J.; Martín-Pérez, E. Giant Malignant Insulinoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 20, 1530–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, D.; Abbasakoor, N.O.; Healy, M.L.; O’Shea, D.; Maguire, D.; Muldoon, C.; Sheahan, K. Metastatic Insulinoma in a Patient with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 2011, 124078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Gorden, P.; Libutti, S.K. Insulinoma. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 89, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg, B.; Cochran, C.; Skarulis, M.C.; Libutti, S.K.; Alexander, H.R.; Wood, B.J.; Chang, R.; Kleiner, D.E.; Gorden, P. Malignant Insulinoma: Spectrum of Unusual Clinical Features. Cancer 2005, 104, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, A.; Yamashita, T.S.; Glasgow, A.E.; Habermann, E.B.; Thompson, G.B.; Lyden, M.L.; Dy, B.M.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Vella, A.; McKenzie, T.J. Comparison of Benign and Malignant Insulinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Herder, W.W.; Van Schaik, E.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Feelders, R.A. New Therapeutic Options for Metastatic Malignant Insulinomas. Clin. Endocrinol. 2011, 75, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moris, D.; Giannis, D.; Karachaliou, G.-S.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Karaolanis, G.; Papalampros, A.; Felekouras, E. Insulinomas: From Diagnosis to Treatment. A Review of the Literature. JBUON 2020, 25, 1302–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.; Watkin, D.; Evans, J.; Yip, V.; Cuthbertson, D.J. Multidisciplinary Management of Refractory Insulinomas. Clin. Endocrinol. 2018, 88, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursan, N.; Yildirgan, M.I.; Atamanalp, S.S.; Sahin, O.; Gursan, M.S. Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of the Pancreas. Eurasian J. Med. 2009, 41, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, A.; Sutherland, T.; Little, A.F. Part 1: CT Characterisation of Pancreatic Neoplasms: A Pictorial Essay. Insights Imaging 2011, 2, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, F.J.; McMahon, M.M.; O’Brien, P.C.; Ballard, D.J. Functioning Insulinoma—Incidence, Recurrence, and Long-Term Survival of Patients: A 60-Year Study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1991, 66, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, R.; Hong, X.; Wu, H.; Han, X.; Wu, W. Metastatic Insulinoma: Exploration from Clinicopathological Signatures and Genetic Characteristics. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1109330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ping, F.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Yuan, T.; Fu, Y.; Feng, K.; Xia, W.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Clinical Management of Malignant Insulinoma: A Single Institution’s Experience over Three Decades. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto-Saldarriaga, C.; Builes-Montaño, C.E.; Arango-Toro, C.M.; Manotas-Echeverry, C.; Pérez-Cadavid, J.C.; Álvarez-Payares, J.C.; Rodríguez-Arrieta, L.A. Insulinoma-Related Endogenous Hypoglycaemia with a Negative Fasting Test: A Case Report and Literature Review. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2022, 9, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’alessandro, M.; Mariani, P.; Lomanto, D.; Carlei, F.; Lezoche, E.; Speranza, V. Serum Neuron-Specific Enolase in Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Tumor Biol. 1992, 13, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, K.; Kato, K.; Nagasaka, A.; Miura, K.; Kawase, K.; Miyakawa, S.; Tei, T.; Ohtani, S.; Inagaki, M.; Shinoda, S.; et al. Immunohistochemical Study of Neuron-Specific Enolase and CA 19-9 in Pancreatic Disorders. The Value of Neuron-Specific Enolase as a Marker for Islet Cell and Nerve Tissue. Gastroenterology 1986, 91, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magi, L.; Marasco, M.; Rinzivillo, M.; Faggiano, A.; Panzuto, F. Management of Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2023, 24, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polowczyk, B.; Kaluzny, M.; Bolanowski, M. Somatostatin Analogues in the Therapy of Neuroendocrine Tumors: Indications, Contraindications, Side-Effects. Postep. Hig. Med. Dosw. 2020, 74, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos-Kudła, B.; Ćwikła, J.; Jarząb, B.; Jeziorski, K.; Królicki, L.; Krzakowski, M.; Nasierowska-Guttmejer, A.; Rydzewska, G.; Stachura, J.; Szawłowski, A. Polish Recommendation for Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastroenteropancreatic Tumors (GEP NET). Oncol. Clin. Pract. 2006, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg, J.; El-Haddad, G.; Wolin, E.; Hendifar, A.; Yao, J.; Chasen, B.; Mittra, E.; Kunz, P.L.; Kulke, M.H.; Jacene, H.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of 177 Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, P.; Martínez, A.; Gajate, P.; Alonso, T.; Navarro, T.; Díez, J.J. Long-Term Effect of 177Lu-Dotatate on Severe and Refractory Hypoglycemia Associated with Malignant Insulinoma. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2019, 5, e330–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Costa, R.; Bacchi, C.E.; Almeida Filho, P. Metastatic Insulinoma Managed with Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analog. Case Rep. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 252159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makis, W.; Mccann, K.; Mcewan, A.J.B. Metastatic Insulinoma Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Treated with 177Lu-DOTATATE Induction and Maintenance Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy: A Suggested Protocol. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novruzov, F.; Mehmetbeyli, L.; Aliyev, J.A.; Abbasov, B.; Mehdi, E. Metastatic Insulinoma Controlled by Targeted Radionuclide Therapy with 177Lu-DOTATATE in a Patient with Solitary Kidney and MEN-1 Syndrome. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2019, 44, E415–E417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, M.; Fortunati, E.; Zanoni, L.; Fanti, S.; Ambrosini, V. The Role of Combined FDG and SST PET/CT in Neuroendocrine Tumors. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 37, e13474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.L.; Hayes, A.R.; Karfis, I.; Conner, A.; Furtado O’Mahony, L.; Mileva, M.; Bernard, E.; Roach, P.; Marin, G.; Pavlakis, N.; et al. Dual [68Ga]DOTATATE and [18F]FDG PET/CT in Patients with Metastatic Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Multicentre Validation of the NETPET Score. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, E.; Kłosowski, P.; Dubowik, M.; Pȩksa, R.; Sworczak, K. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Ethanol Ablation of Insulinoma. Endokrynol. Pol. 2020, 71, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Viswanathan, K.; Goyal, A.; Rao, R. Insulinoma-Associated Protein 1 (INSM1) Is a Robust Marker for Identifying and Grading Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020, 128, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, W.; Tao, J.; Yao, Y. INSM1 Promotes Breast Carcinogenesis by Regulating C-MYC. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2023, 13, 3500–3516. [Google Scholar]

- Razvi, H.; Tsang, J.Y.; Poon, I.K.; Chan, S.K.; Cheung, S.Y.; Shea, K.H.; Tse, G.M. INSM1 Is a Novel Prognostic Neuroendocrine Marker for Luminal B Breast Cancer. Pathology 2021, 53, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesdorffer, C.S.; Stoopler, M.; Javitch, J. Aggressive Insulinoma with Bone Metastases. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1989, 12, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libutti, S.; Taye, A. Diagnosis and Management of Insulinoma: Current Best Practice and Ongoing Developments. Res. Rep. Endocr. Disord. 2015, 5, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, M.; Urbanczuk, M.; Zwolak, A.; Dudzinska, M.; Lenart-Lipinska, M.; Tarach, J.S. Insulinoma- from Diagnosis to Full Recovery. Case Study. Endocr. Abstr. 2017, 49, EP144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ma, Q.; Fu, Y. Case Report: Insulinoma Presenting as Excessive Daytime Somnolence. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 712392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oziel-Taieb, S.; Maniry-Quellier, J.; Chanez, B.; Poizat, F.; Ewald, J.; Niccoli, P. Pasireotide for Refractory Hypoglycemia in Malignant Insulinoma- Case Report and Review of the Literature. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 860614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Lampart, S.; Metzger, J.; Fischli, S. Case Report of a Pancreatic Insulinoma Misdiagnosed as Epilepsy. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, 2020–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinhosa Bastos, M.A.; da Silva Caires, I.; Boschi Portella, R.; Nascimento Martins, R.; Reverdito, R.; Reverdito, S.; Moro, N. Insulinoma with Peripheral Neuropathy: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2023, 17, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhamisy, A.; Nasani, M. A Rare Case of Insulinoma Presented with Neurological Manifestations: A Case Report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 108, 108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, O.; Sendur, M.A.; Dumlu, G.; Yildirim, F.; Taskaldiran, I.; Soydal, C.; Ersoy, R.; Cakir, B. Case Report: Management of a Patient with Malignant Insulinoma. Endocr. Abstr. 2018, 56, EP9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashidengo, P.R.; Quayson, F.W.; Abebrese, J.T.; Negumbo, L.; Enssle, C.; Kidaaga, F. Varied Presentations of Pancreatic Insulinoma: A Case Report. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 42, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, F.; Moradi, L. Pancreatic Insulinoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin. Case Rep. Rev. 2018, 4, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarris, G.; Rouland, A.; Guillen, K.; Loffroy, R.; Lariotte, A.C.; Rat, P.; Bouillet, B.; Andrianiaina, H.; Petit, J.M.; Martin, L. Case Report: Giant Insulinoma, a Very Rare Tumor Causing Hypoglycemia. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1125772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Test | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Vimentin Ab2 | +/− |

| Cytokeratin Clone AE1/AE3 | − |

| Cytokeratin 7 | − |

| Chromogranin A | + |

| Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE) | + |

| Synaptophysin | + |

| Marker | Result | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatogranin A | 43.2 µg/dL | 0–100 µg/dL |

| Gastrin | 69.7 pg/mL | 13–115 pg/mL |

| NSE | 13.3 µg/dL | 0–18.3 µg/dL |

| Calcitonin | 104 pg/mL | 0–11.5 pg/mL |

| 0 min. | 30 min. | 60 min. | 120 min. | 180 min. | 240 min. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 124 (N: 70–99) | 217 | 260 | 373 | 299 | 189 |

| Insulin (μIU/mL) | 2 (N: <29) | 3.52 | 2 | 5.95 | 11.2 | 75.1 |

| Blood Test | Result |

|---|---|

| Glucose | 33 mg/dL |

| Insulin | 27.1 μIU/mL |

| C-peptide | 6.8 ng/mL |

| 0 min. | 60 min. | 120 min. | 180 min. | 240 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose mg/dL | 160 | 137 | 158 | 143 | 133 |

| Insulin μIU/mL | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 |

| Result | Normal Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Chromogranin A | 337.3 µg/dL | <100 µg/dL |

| NSE | 75.85 ng/dL | <18.3 ng/dL |

| 5HIAA | 7.15 mg/24 h | 2–9 mg/24 h |

| Ki67 | Synaptophysin | Chromogranin A | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left side | 30% | + | + |

| Right side | 50% | + | + |

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 2009 | First symptoms: abdominal pain; pancreatic tumor confirmed in USG examination |

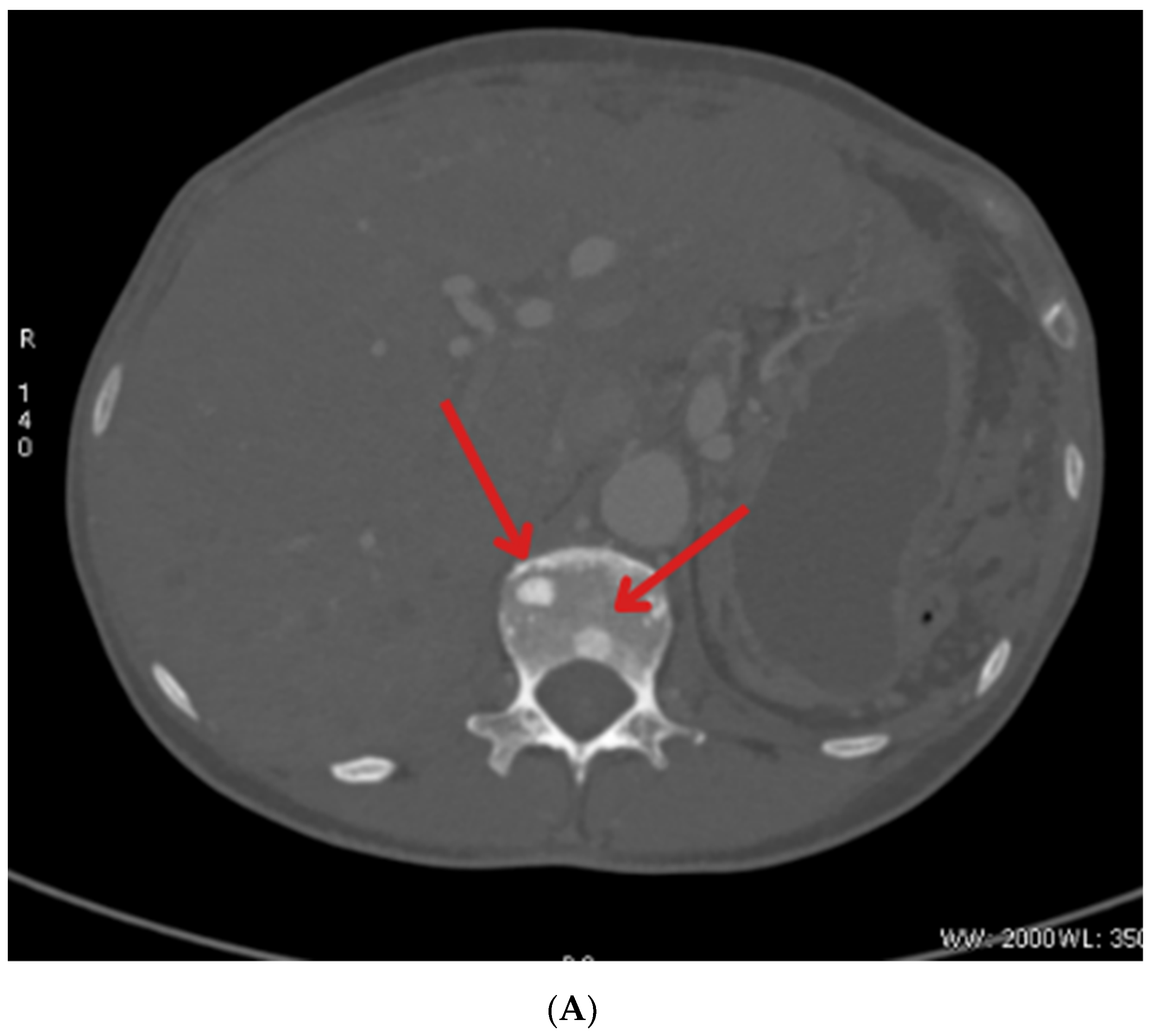

| July 2009 | Distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy; histopathological exam: solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas |

| September 2019 | Segmentectomy (S5-S4b) with cholecystectomy with the histopathological recognition of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) metastasis to the liver characterized as NET G2, Ki67—5% |

| January 2022 | Short episode of loss of consciousness with convulsion due to hypoglycemia; repeated states of hypoglycemia—hospitalization at the Neurology Department in Wroclaw |

| April 2022 | Diagnostic at the Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Isotope Therapy in Wrocław—72 h fasting test excluding insulinoma; diagnosis of type 3 diabetes; metastatic process found in the liver in PET-FDG |

| May 2022 | Persistent hypoglycemia with elevated insulin and C-peptide levels → diagnosis of insulinoma; start of treatment using somatostatin and diazoxide; metastatic tumor in segment I of the liver confirmed in MRI |

| June 2022 | EUS with hepatic biopsy → NET with higher malignancy, G2/G3, Ki67—up to 20%. |

| August 2022 | Median upper relaparotomy with alcoholization of the liver tumor |

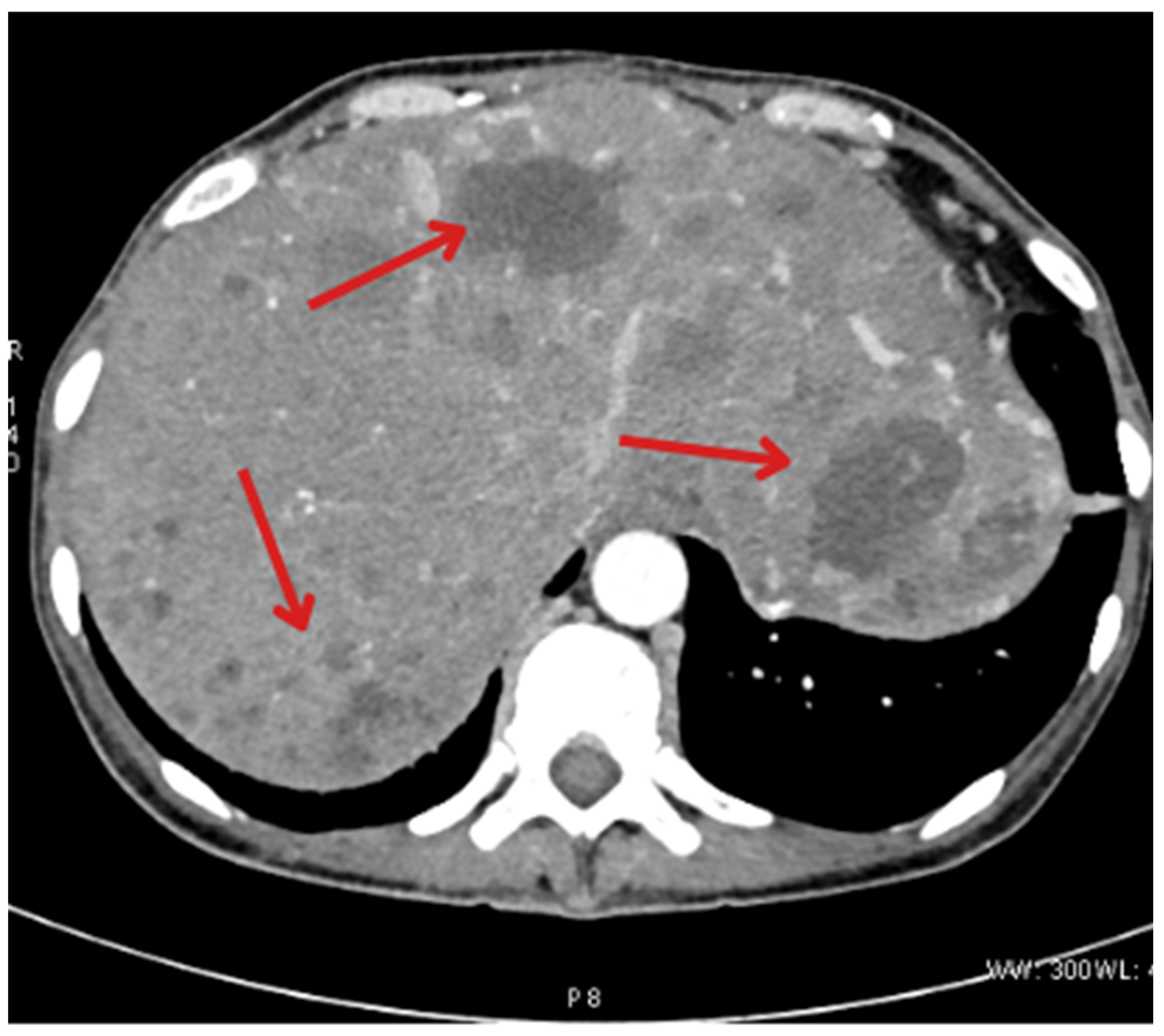

| November 2022 | Follow-up CT showing new metastases in S2, S3, and S6 of the liver |

| January 2023 | Follow-up PET showing foci in the liver, head of the pancreas, bones, and cervical lymph nodes |

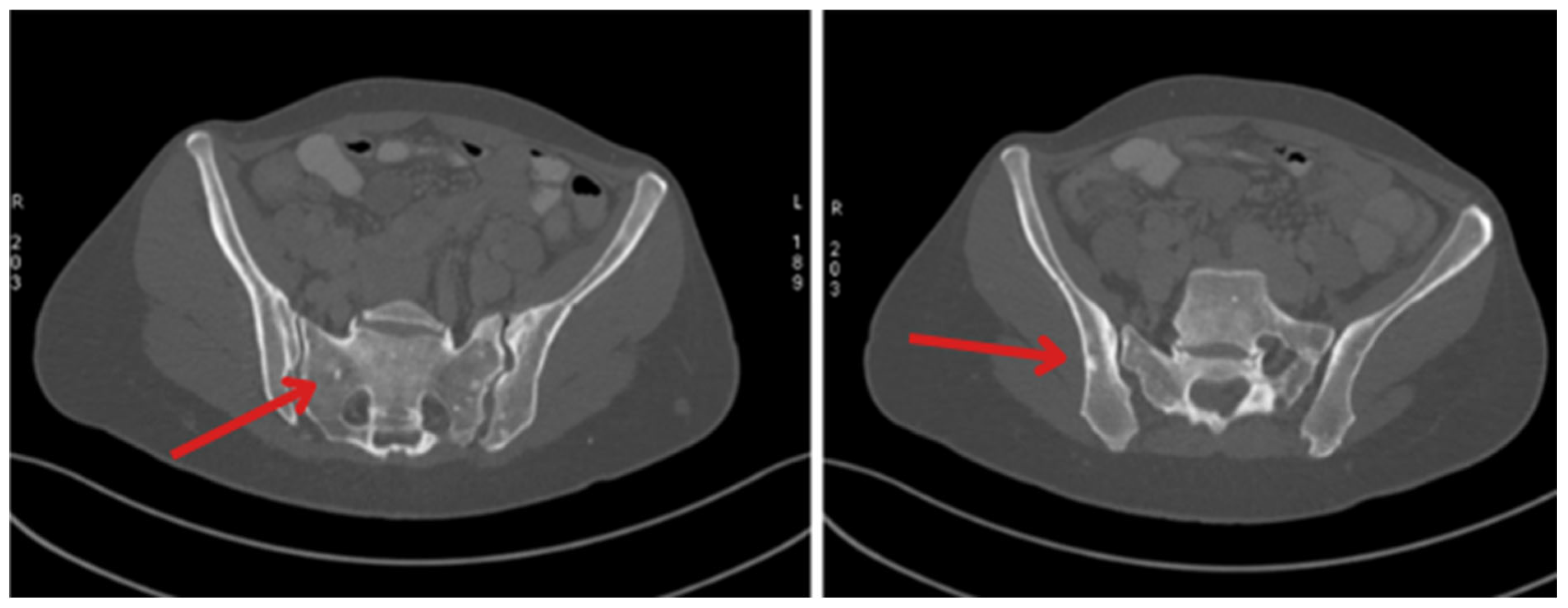

| May 2023 | Beginning of Lutathera treatment CT scan: metastases in the liver, bone sclerosis, enlarged lymph nodes |

| June 2023 | Administration of continuous glucose monitoring with FSM Breast ultrasound and mammography: lesion found in both of the mammary glands (right breast—BIRADS4; left breast—BIRADS2) |

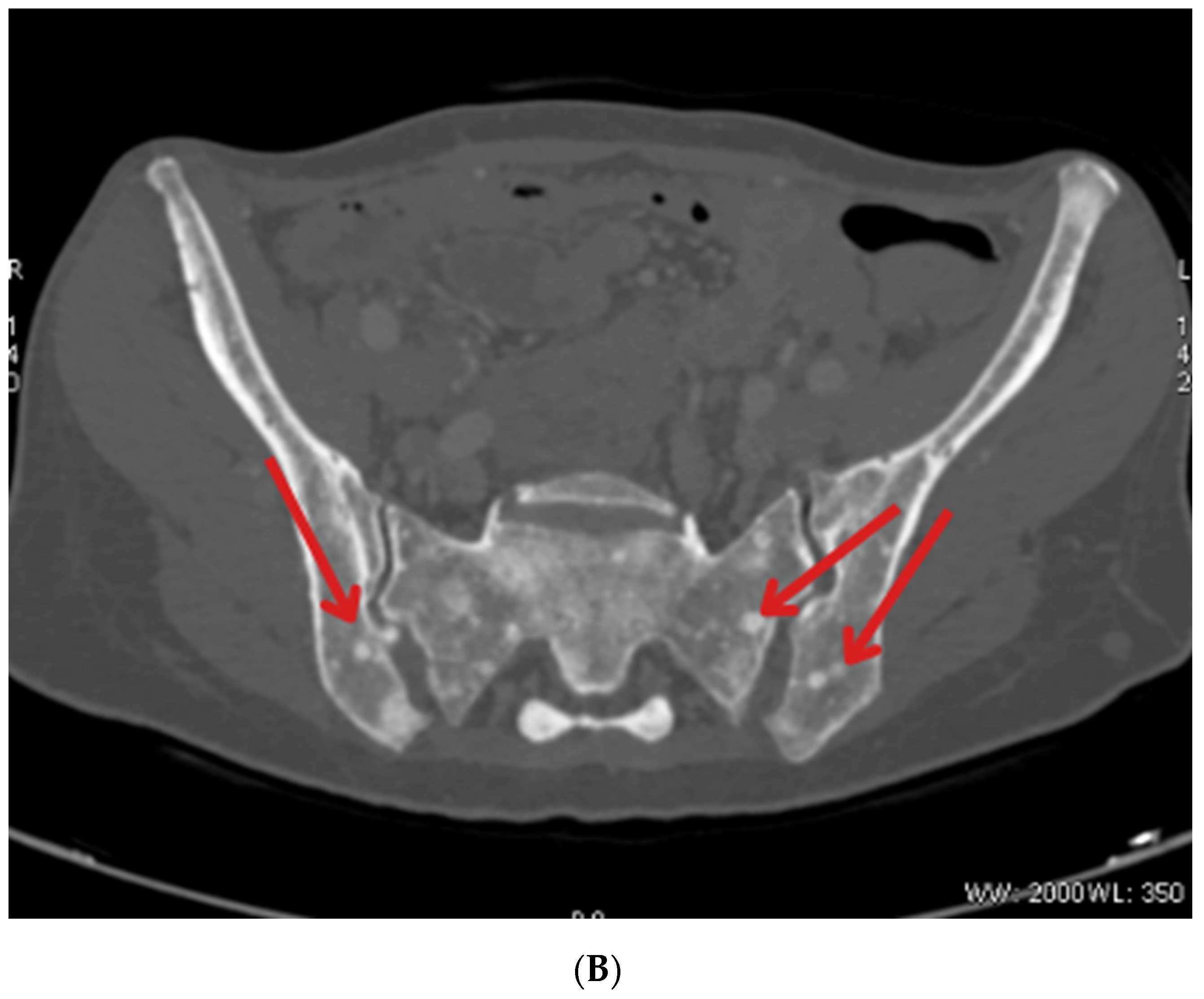

| July and August 2023 | Biopsy of the mammary glands: metastases with high proliferation markers (triple negative malignant neoplasm) NET G3, Ki67—30% for left breast and 50% for right breast Administration of a second dose of Lutathera |

| October 2023 | Significant progression of metastases in the liver and bones (spine, ribs, pelvis), and periaortic and pelvic lymphadenopathy The patient was referred to palliative hospice care, resigned from further PRPRT treatment |

| November 2023 | Chemotherapy with temozolomide—I cycle |

| 27 December 2023 | Patient died |

| Similar Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Data | Symptoms | Type of Treatment | Effect of Treatment | Citation | |

| 1 | A 16-year-old male, South America |

| Surgical treatment—enucleation of the tumor. No metastases were detected. | The patient feels a significant improvement in his condition.The symptoms have completely disappeared. | [45] |

| 2 | A 47-year-old female, Asia |

| Surgical treatment—laparoscopic partial distal pancreatectomy. No metastases were detected. | Three months after surgery, the patient reported feeling well, and follow-up tests (glucose, insulin, C-peptide) showed normal results. | [46] |

| 3 | A 41-year-old female, Europe |

| Surgical treatment—distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Pharmacological treatment:

Hepatic and lymph node metastases have been reported. Tumor infiltration of the perihilar tissues was found. | The patient experienced respiratory distress likely due to infection or drug-associated pneumonitis. She developed acute respiratory distress syndrome. Unfortunately, she died three months after the initial diagnosis due to ARDS. | [47] |

| 4 | A 26-year-old female, Africa |

| Surgical treatment—enucleation of the tumor. No metastases were detected. | Following the surgery, the patient had a full recovery. The patient no longer experienced symptoms such as fatigue, increased appetite, seizures, or loss of consciousness. | [48] |

| 5 | A 43-year-old female, Asia |

| Surgical treatment—enucleation of the tumor. No metastases were detected. | After the surgical treatment, her glucose levels rose to the diabetic range, suggesting that the hypoglycemic symptoms were effectively managed. | [49] |

| 6 | A 38-year-old female, Europe |

| Surgical treatment—laparoscopic partial distal pancreatectomy. Pharmacological treatment:

| After surgery, the patient’s insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide, and glucose levels returned to normal. After 16 months, the patient had lost 4.2 kg and did not report any specific complaints. | [50] |

| 7 | A 53-year-old male, Europe |

| Surgical treatment—removal of the tumor. No metastases were detected. | After the surgery, all symptoms subsided, and the patient did not require any additional treatment. | [41] |

| 8 | A 14-year-old female, Asia |

| Surgical treatment—laparoscopic partial distal pancreatectomy. No metastases were detected. | Symptoms improved significantly, including the disappearance of daytime sleepiness and abnormal behavior during sleep. The patient’s blood glucose levels normalized. | [42] |

| 9 | A 64-year-old female, Europe |

| Pharmacological treatment:

| Patient’s glycemic control improved significantly, and hypoglycemic episodes became much less frequent and severe. Blood glucose levels were completely normalized for over 18 months, resulting in a significant improvement in her quality of life. | [43] |

| 10 | A 55-year-old female, Europe |

| Surgical treatment—removal of the tumor. Pharmacological treatment:

| Postoperatively, the patient’s glucose level and insulin regulation normalized, leading to an overall improvement in her health. | [44] |

| 11 | A 65-year-old male, South America |

| Surgical treatment—Subtotal pancreatectomy (90%) with splenectomy. No metastases were detected. | Improvement in glucose control after surgery. Initial postoperative hyperglycemia managed with insulin | [22] |

| 12 | A 54-year-old male, Asia |

| Pharmacological treatment:

| After treatment, the size and activity of the lesions decreased. Hypoglycemic episodes, which previously occurred daily, decreased to 1 episode per year during a 1-year follow-up. | [32] |

| 13 | A 72-year-old female, Europe |

| EUS-guided ethanol ablation (two sessions). No metastases were detected. | After the first session, partial improvement was observed: hypoglycemic episodes occurred less frequently, and the symptoms were milder. After the second session, the treatment appeared to be fully effective, with no hypoglycemic episodes for five months. Adverse effects: mild abdominal pain on the day of the procedure and a transient six-fold elevation of lipase activity, which normalized within 72 h. | [35] |

| 14 | A 60-year-old male, North America |

| Pharmacological treatment:

Metastatic lesion was demonstrated in the liver and bones. | Despite the treatment administered, hypoglycemic symptoms progressed. Sepsis appeared. The patient died after 11 months of diagnosis. | [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antosz-Popiołek, K.; Koga-Batko, J.; Suchecki, W.; Stopa, M.; Zawadzka, K.; Hajac, Ł.; Bolanowski, M.; Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska, A. History of an Insidious Case of Metastatic Insulinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124028

Antosz-Popiołek K, Koga-Batko J, Suchecki W, Stopa M, Zawadzka K, Hajac Ł, Bolanowski M, Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska A. History of an Insidious Case of Metastatic Insulinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124028

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntosz-Popiołek, Katarzyna, Joanna Koga-Batko, Wojciech Suchecki, Małgorzata Stopa, Katarzyna Zawadzka, Łukasz Hajac, Marek Bolanowski, and Aleksandra Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska. 2025. "History of an Insidious Case of Metastatic Insulinoma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124028

APA StyleAntosz-Popiołek, K., Koga-Batko, J., Suchecki, W., Stopa, M., Zawadzka, K., Hajac, Ł., Bolanowski, M., & Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska, A. (2025). History of an Insidious Case of Metastatic Insulinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124028