Hydrops Fetalis Caused by Congenital Syphilis: Case Series and a Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Case Series Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Review Results

3.2. Case Series Presentation

4. Discussion

4.1. Intramuscular BPG vs. Intravenous PG Regimen

4.2. The Role of Intrauterine Blood Transfusion (IUT)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rac, M.W.; Bryant, S.N.; McIntire, D.D.; Cantey, J.B.; Twickler, D.M.; Wendel, G.D., Jr.; Sheffield, J.S. Progression of ultrasound findings of fetal syphilis after maternal treatment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 211, 426.e1–426.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rac, M.W.; Revell, P.A.; Eppes, C.S. Syphilis during pregnancy: A preventable threat to maternal-fetal health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, A.; Olson, N.; Foster, J.; Contag, S. A Narrative Review of Congenital Syphilis in the United States: Innovative Perspectives on a Complex Public Health and Medical Disease. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2025, 52, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, G.; Unemo, M.; Mårdh, O.; Amato-Gauci, A.J. The resurgence of syphilis in high-income countries in the 2000s: A focus on Europe. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, M.; French, P.; Fifer, H.; Hughes, G.; Wilson, J. Congenital syphilis in England and amendments to the BASHH guideline for management of affected infants. Int. J. STD AIDS 2017, 28, 1361–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furegato, M.; Fifer, H.; Mohammed, H.; Simms, I.; Vanta, P.; Webb, S.; Foster, K.; Kingston, M.; Charlett, A.; Vishram, B.; et al. Factors associated with four atypical cases of congenital syphilis in England, 2016 to 2017: An ecological analysis. Euro Surveill. 2017, 22, 17–00750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machefsky, A.; Hufstetler, K.; Bachmann, L.; Barbee, L.; Miele, K.; O’Callaghan, K. Rising Stillbirth Rates Related to Congenital Syphilis in the United States From 2016 to 2022. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 144, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J. Antibiotics for syphilis diagnosed during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, 2010, CD001143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, L.; Bawdon, R.E.; Sidawi, J.E.; Stettler, R.W.; McIntire, D.M.; Wendel, G.D., Jr. Penicillin levels following the administration of benzathine penicillin G in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 82, 338–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hollier, L.M.; Harstad, T.W.; Sanchez, P.J.; Twickler, D.M.; Wendel, G.D., Jr. Fetal syphilis: Clinical and laboratory characteristics. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workowski, K.A.; Bachmann, L.H.; Chan, P.A.; Johnston, C.M.; Muzny, C.A.; Park, I.; Reno, H.; Zenilman, J.M.; Bolan, G.A. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2021, 70, 1–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.E.; Chauhan, S.P.; Dashe, J.S. Society for maternal-fetal medicine (SMFM) clinical guideline #7: Nonimmune hydrops fetalis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, K.; Baxi, L.; Fox, H.E. False-negative syphilis screening: The prozone phenomenon, nonimmune hydrops, and diagnosis of syphilis during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 163, 975–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.R.; Thorpe, E.M., Jr.; Shaver, D.C.; Hager, W.D.; Sibai, B.M. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis associated with maternal infection with syphilis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 167, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallak, M.; Peipert, J.F.; Ludomirsky, A.; Byers, J. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis and fetal congenital syphilis. A case report. J. Reprod. Med. 1992, 37, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galan, H.L.; Yandell, P.M.; Knight, A.B. Intravenous penicillin for antenatal syphilotherapy. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 1, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElTabbakh, G.H.; Elejalde, B.R.; Broekhuizen, F.F. Primary syphilis and nonimmune fetal hydrops in a penicillin-allergic woman. A case report. J. Reprod. Med. 1994, 39, 412–414. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Z.; Sherer, D.M.; Jacobs, A.; Rotenberg, O. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis due to congenital syphilis associated with negative intrapartum maternal serology screening. Am. J. Perinatol. 1998, 15, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TANER, M.; AKÇ‹N, Ü.; TAfiKIRAN, Ç.; ONAN, A.; ÖNDER, M.; HIMMETO⁄LU, Ö. Congenital Syphilis as a Cause of Hydrops Fetalis in a Woman with Spyhilis Incognito. J. Turkish German Gynecol. Assoc. 2004, 5, 318–320. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.; Chandra, S.; Singh, A.; Kumar, M.; Jain, V.; Turnell, R. Successful outcome with intrauterine transfusion in non-immune hydrops fetalis secondary to congenital syphilis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2010, 32, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Júnior, E.; Martins Santana, E.F.; Rolo, L.C.; Nardozza, L.M.; Moron, A.F. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital syphilis using two- and three-dimensional ultrasonography: Case report. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2012, 2012, 478436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macé, G.; Castaigne, V.; Trabbia, A.; Guigue, V.; Cynober, E.; Cortey, A.; Lalande, V.; Carbonne, B. Fetal anemia as a signal of congenital syphilis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014, 27, 1375–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, F.; Michaux, K.; Rousseau, C.; Ovetchkine, P.; Audibert, F. Syphilis Infection: An Uncommon Etiology of Infectious Nonimmune Fetal Hydrops with Anemia. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2016, 39, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duby, J.; Bitnun, A.; Shah, V.; Shannon, P.; Shinar, S.; Whyte, H. Non-immune Hydrops Fetalis and Hepatic Dysfunction in a Preterm Infant with Congenital Syphilis. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramis Fernández, S.M.; Alsina-Casanova, M.; Herranz-Barbero, A.; Aldecoa-Bilbao, V.; Borràs-Novell, C.; Salvia-Roges, D. Hydrops fetalis caused by congenital syphilis: An ancient disease? Int. J. STD AIDS 2019, 30, 1436–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Montaño, A.M.; Niño-Alba, R.; Páez-Castellanos, E. Congenital syphilis with hydrops fetalis: Report of four cases in a general referral hospital in Bogota, Colombia between 2016–2020. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2021, 72, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M.; Poliquin, V. Exploring management of antenatally diagnosed fetal syphilis infection. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2022, 48, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinicu, A.; Penalosa, P.; Crosland, B.A.; Steller, J. Complete Resolution of Nonimmune Hydrops Fetalis Secondary to Maternal Syphilis Infection. AJP Rep. 2023, 13, e21–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarali, N.; Balaban, I.; Akyurek, N.; Ucar, S.; Zorlu, P. Hemophagocytosis: The cause of anemia and thrombocytopenia in congenital syphilis. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2009, 26, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonne, B.; Nguyen, A.; Cynober, E.; Castaigne, V.; Cortey, A.; Brossard, Y. Prenatal diagnosis of anoxic cerebral lesions caused by profound fetal anemia secondary to maternal red blood cell alloimmunization. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luewan, S.; Apaijai, N.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Tongsong, T. Fetal hemodynamic changes and mitochondrial dysfunction in myocardium and brain tissues in response to anemia: A lesson from hemoglobin Bart’s disease. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari, G.; Norton, M.E.; Stone, J.; Berghella, V.; Sciscione, A.C.; Tate, D.; Schenone, M.H. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Clinical Guideline #8: The fetus at risk for anemia--diagnosis and management. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Practice Bulletin No. 192: Management of Alloimmunization During Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e82–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Author (Year-Country) | Age | Parity | GA at Diagnosis of NIHF | GA at Diagnosis of Syphilis | MCA-PSV | MoM | Hb | Treatment | IUT | Response | GA at Birth | Route | BW | Sex | Neonatal Outcomes | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bercowitz (1990-USA) [13] | 26 | G8P3 | 32 | Postnatal | no | no | no | 32 | CS | 2525 | M | Survive | Non-reactive (prozone); CS | |||

| 2 | Bercowitz (1990-USA) [13] | 21 | G3P1 | 32 | Postnatal | no | no | no | 32 | CS | 1460 | M | Survive | Non-reactive (prozone); CS | |||

| 3 | Bercowitz (1990-USA) [13] | 36 | G6P4 | Term | Postnatal | no | no | no | Term | CS | M | ND | Non-reactive (prozone); CS (petechiae, hepatosplenogemagly, thrombocytopenia), died d1 | ||||

| 4 | Bercowitz (1990-USA) [13] | 30 | G4P1 | 27 | 27 | no | no | no | 2070 | DFU | Non-reactive (prozone); CS (HD, petechiae, splenogemagly, thrombocytopenia) | ||||||

| 5 | Barton (1992-USA) [14] | 21 | G2P1 | 31 | 31 | no | IM | no | partial | 31 | CS | 3540 | F | Survive | CS (metaphyseal rarefaction in all long bones) | ||

| 6 | Barton (1992-USA) [14] | 18 | G2P0 | 35 | 35 | no | NS | no | partial | 35 | CS | 2700 | F | Survive | Fetal distress, HF present | ||

| 7 | Barton (1992-USA) [14] | 21 | G2P0 | 34 | 34 | no | IM | no | partial | 34 | CS | 2530 | M | Survive | Fetal distress | ||

| 8 | Hallak (1992-USA) [15] | 16 | G2P1 | 28 | 28 | no | IV | no | partial | 28 | CS | 1546 | F | Survive | Fetal distress, HF present (improved), ascites neurosyphilis | ||

| 9 | Galan (1993-USA) [16] | 21 | G2P1 | 24 | 24 | no | IV | no | complete | 37 | Vg | Survive | IM BPG 1 dose HD worsening → change to IV PG complete disappeared in 3 weeks | ||||

| 10 | EITabbakh (1994-USA) [17] | 22 | G4P2 | 26 | 26 | no | IM | no | complete | 38 | Vg | 2310 | M | Survive | Allergic to penicillin → desensitization; HD disappeared, no CS | ||

| 11 | Levine (1998-USA) [18] | 31 | G3P2 | 29 | Postnatal | no | no | no | 29 | CS | 1825 | M | ND | Non-reactive (prozone); CS Hydrops not improved, RPR 1:1024 | |||

| 12 | TANER (2004-Turkey) [19] | 20 | G1P0 | 28 | Postnatal | no | no | no | no response | 28 | 2200 | F | DFU | DFU (1 d after diagnosis) | |||

| 13 | Chen (2010-Canada) [20] | 17 | G1P0 | 27 | 28 | yes | 1.55 | 5.5 | IV | yes | complete | 35 | Vg | 2390 | M | Survive | Penicillin 4 mU IV 14 d; HD disappeared (2 wk of IUT 30 wk), no CS |

| 14 | Arujo (2012-Brazil) [21] | 21 | G1P0 | 25 | 32 | no | IM | no | partial | 33 | CS | 3095 | Survive | PGS Gradually improved | |||

| 15 | Mace (2014-France) [22] | 17 | G1P0 | 34 | Postnatal | yes | 1.5 | 8.4 | no | yes | partial | 35 | CS | 2300 | F | Survive | Not obvious improved, titer 1/5120, Start Extencillin D3 after birth |

| 16 | Mace (2014-France) [22] | 27 | NS | 26 | 17 | yes | 2 | no | no | 26 | Vg | 720 | F | DFU | |||

| 17 | Fuchs (2016-Canada) [23] | 19 | G2P0 | 23 | 23 | yes | 2.1 | 8.2 | IM | yes | no response | 23 | Vg | 858 | F | DFU | Fetal distress; sinusoidal FHR prior to IUT; MCA decreased to 0.81 after BPG/IUT |

| 18 | Duby (2019-Canada) [24] | 28 | G5P2 | 28 | 31 | yes | 1.84 | 5.5 | no | yes | partial | 31 | 1710 | Survive | At birth, hydrops was present; NB improve with IV PG 14 d | ||

| 19 | Ramis (2019-Spain) [25] | 23 | G3P0 | 32 | Postnatal | no | no | 32 | CS | 2510 | M | ND | Fetal distress; no treatment; die d2 after birth | ||||

| 20 | Camacho-Montano (2021-Colombia) [26] | 17 | G2P1 | 26 | 26 | yes | mild anemia | IV | no | partial | 37 | Vg | 2820 | M | Survive | HD improved in 14 d; negative for congenital syphilis | |

| 21 | Camacho-Montano (2021-Colombia) [26] | 28 | G2P1 | 28 | 28 | yes | no anemia | IV | no | complete | 37 | Vg | 2325 | M | Survive | MCA-PSV normal; HF disappeared | |

| 22 | Camacho-Montano (2021-Colombia) [26] | 20 | G2P1 | 30 | 16 | yes | no anemia | IM | no | partial | 30 | CS | 1260 | F | Survive | Fetal distress; improve after birth | |

| 23 | Camacho-Montano (2021-Colombia) [26] | 18 | G3P2 | 29 | 29 | yes | severe anemia | IV | no | complete | 36 | Vg | 2460 | Survive | HD resolve in 7 d | ||

| 24 | Rosenthal (2022-Canada) [27] | 29 | G4P3 | 19 | 19 | yes | 1.37 | IV | no | no response | 21 | Vg | 747 | F | DFU | Primary Sy, 9 d worsening HD (99th centile); placenta 387 (twice normal) | |

| 25 | Dinicu (2023-USA) [28] | 38 | G5P3 | 28 | 29 | yes | 1.49 | IM | no | complete | 37 | CS | M | Survive | BPG IM, 2.4 mU (3 doses) Hydrops disappeared in 6 days after penicillin first dose; pre-eclampsia with severe features | ||

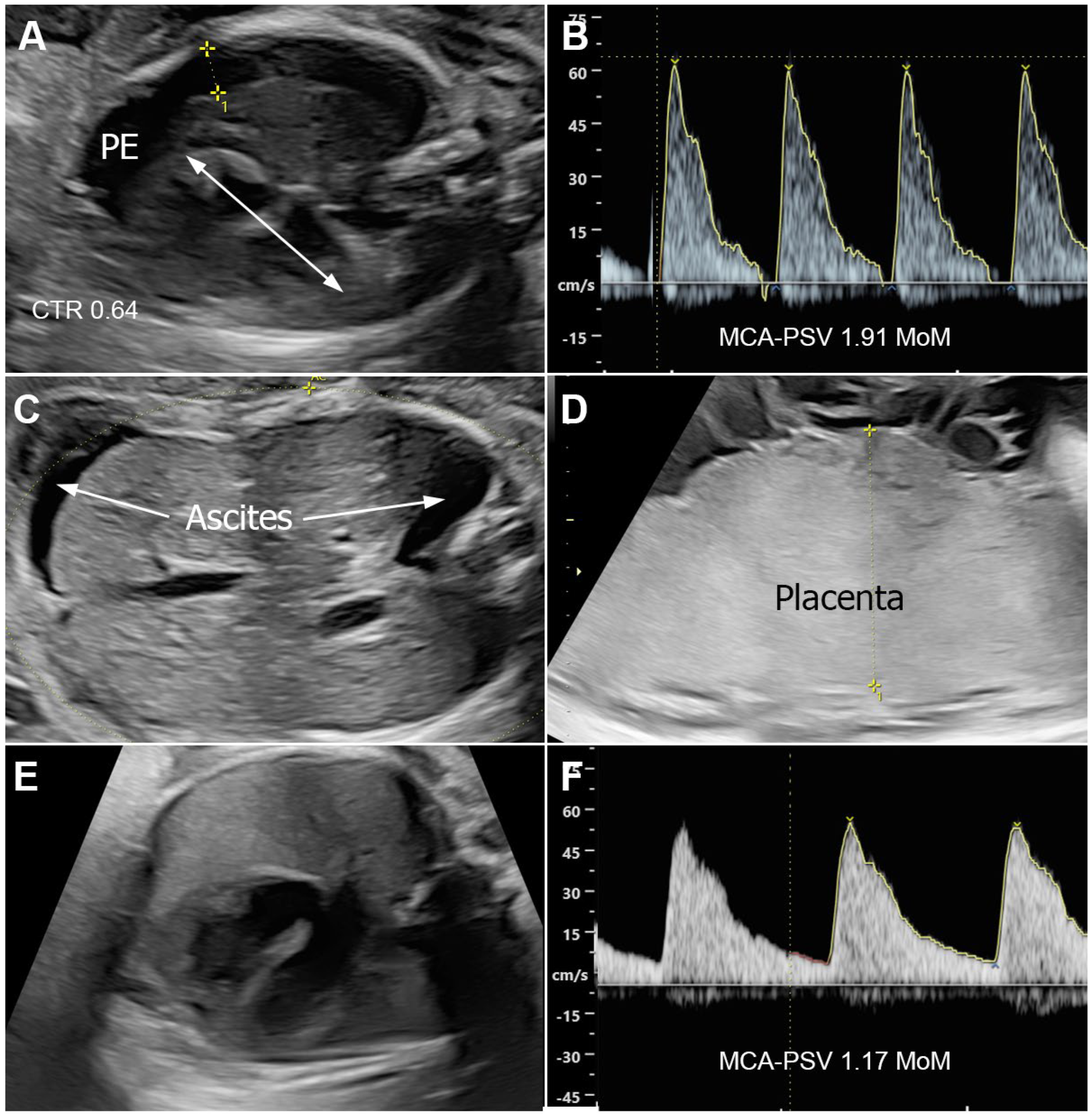

| 26 | This study (2025-Thailand) | 22 | G1P0 | 26 | 26 | yes | 2.17 | IM | no | no response | 30 | CS | 1328 | F | ND | Fetal distress; BPG IM, 2.4 mU (2 dose); HF worsening, died 3 h after birth | |

| 27 | This study (2025-Thailand) | 23 | G3P2 | 30 | 30 | yes | 2.01 | IV | no | complete | 38 | Vg | 2420 | F | Survive | HF disappeared in 3 weeks after penicillin first dose (no JHR) | |

| 28 | This study (2025-Thailand) | 19 | G1P0 | 24 | 24 | yes | 2.23 | IM | no | no response | 25 | Vg | 850 | M | DFU | BPG IM, 2.4 mU (1 dose); Hydrops fetalis, worsening | |

| 29 | This study (2025-Thailand) | 19 | G1P0 | 24 | 25 | yes | 2.35 | 7.2 | IV | yes | complete | 38 | Vg | 3200 | M | Survive | Hydrops disappeared in 3 weeks after IUT |

| 30 | This study (2025-Thailand) | 22 | G3P2 | 26 | 26 | yes | 1.91 | IM | no | complete | 38 | Vg | 2850 | F | Survive | BPG IM, 2.4 mU × 3; Hydrops disappeared in 5 weeks after penicillin first dose (no JHR) | |

| Continuous Variables | Total Valid Number (N) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 30 | 23.0 | 5.6 |

| Gestational age at diagnosis of hydrops (week) | 29 | 28.0 | 3.7 |

| Gestational age at diagnosis of syphilis (week) | 23 | 26.7 | 4.8 |

| Gestational age at birth (week) | 28 | 32.4 | 4.8 |

| Birth weight (g) | 27 | 2094 | 779 |

| Categorical Variables | Total Valid Number (N) | Number (n) | Percentage |

| Parity: | 29 | ||

| 10 | 34.5 | |

| 19 | 65.5 | |

| MCA-PSV measurement | 29 | 16 | 55.2 |

| Prenatal treatment | 29 | ||

| 10 | 34.5 | |

| 10 | 34.5 | |

| 9 | 31.0 | |

| Intrauterine blood transfusion | 30 | 5 | 16.7 |

| Response to therapy | 23 | ||

| 5 | 21.7 | |

| 5 | 39.1 | |

| 9 | 39.1 | |

| Route of delivery | 27 | ||

| 13 | 48.1 | |

| 14 | 51.9 | |

| Preterm birth | 28 | 20 | 71.4 |

| Neonatal sex | 25 | ||

| 13 | 52.0 | |

| 12 | 48.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yanase, Y.; Sirilert, S.; Jatavan, P.; Pomrop, M.; Phirom, K.; Tongsong, T. Hydrops Fetalis Caused by Congenital Syphilis: Case Series and a Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113671

Yanase Y, Sirilert S, Jatavan P, Pomrop M, Phirom K, Tongsong T. Hydrops Fetalis Caused by Congenital Syphilis: Case Series and a Comprehensive Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113671

Chicago/Turabian StyleYanase, Yuri, Sirinart Sirilert, Phudit Jatavan, Mallika Pomrop, Krittaya Phirom, and Theera Tongsong. 2025. "Hydrops Fetalis Caused by Congenital Syphilis: Case Series and a Comprehensive Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113671

APA StyleYanase, Y., Sirilert, S., Jatavan, P., Pomrop, M., Phirom, K., & Tongsong, T. (2025). Hydrops Fetalis Caused by Congenital Syphilis: Case Series and a Comprehensive Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113671