Development of a Risk Score for the Prediction and Management of Pre-Eclampsia in Low-Resource Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

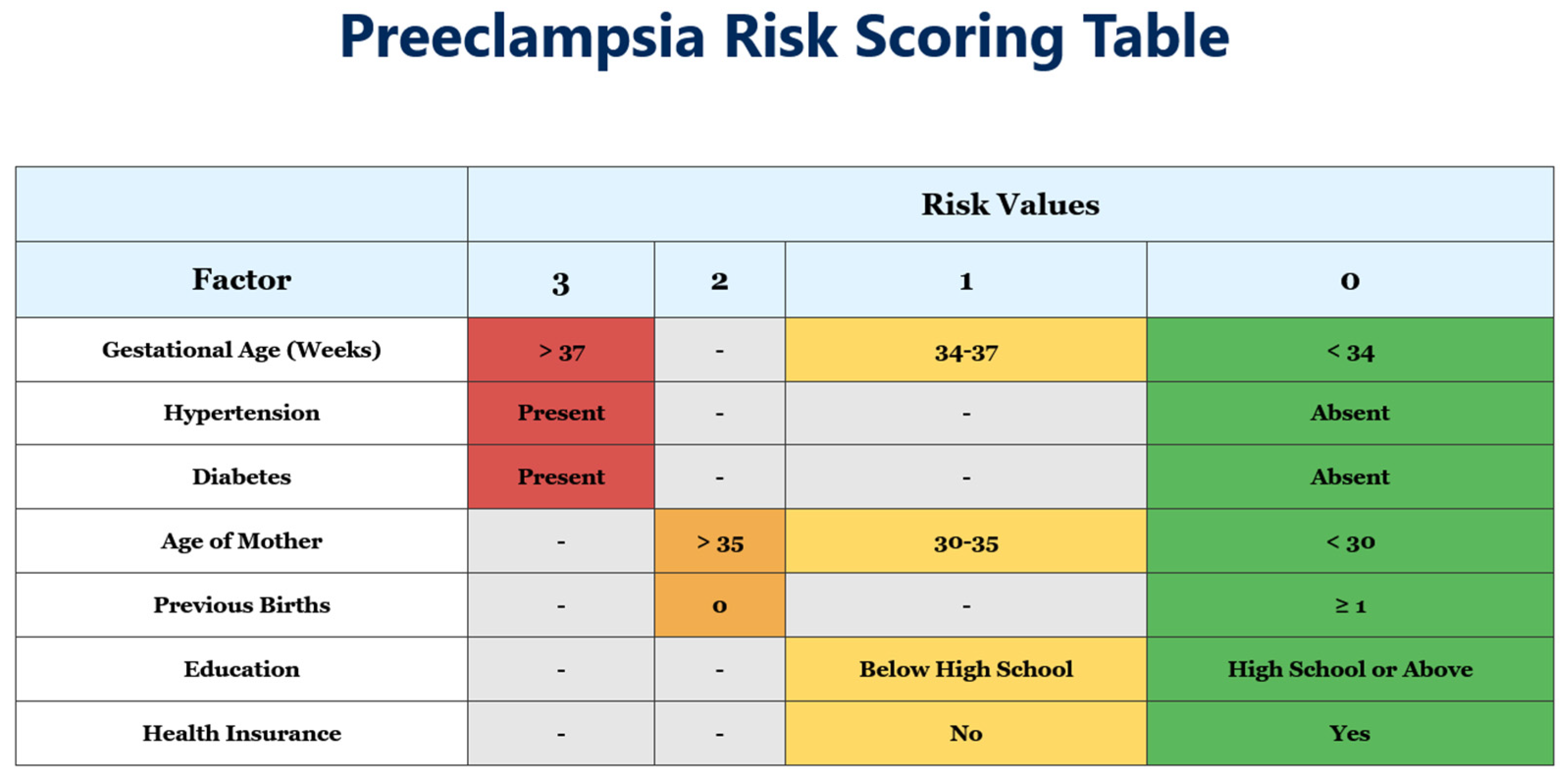

2.2. Data Collection and Predictive Model Development

2.3. Model Validation and Outcome Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

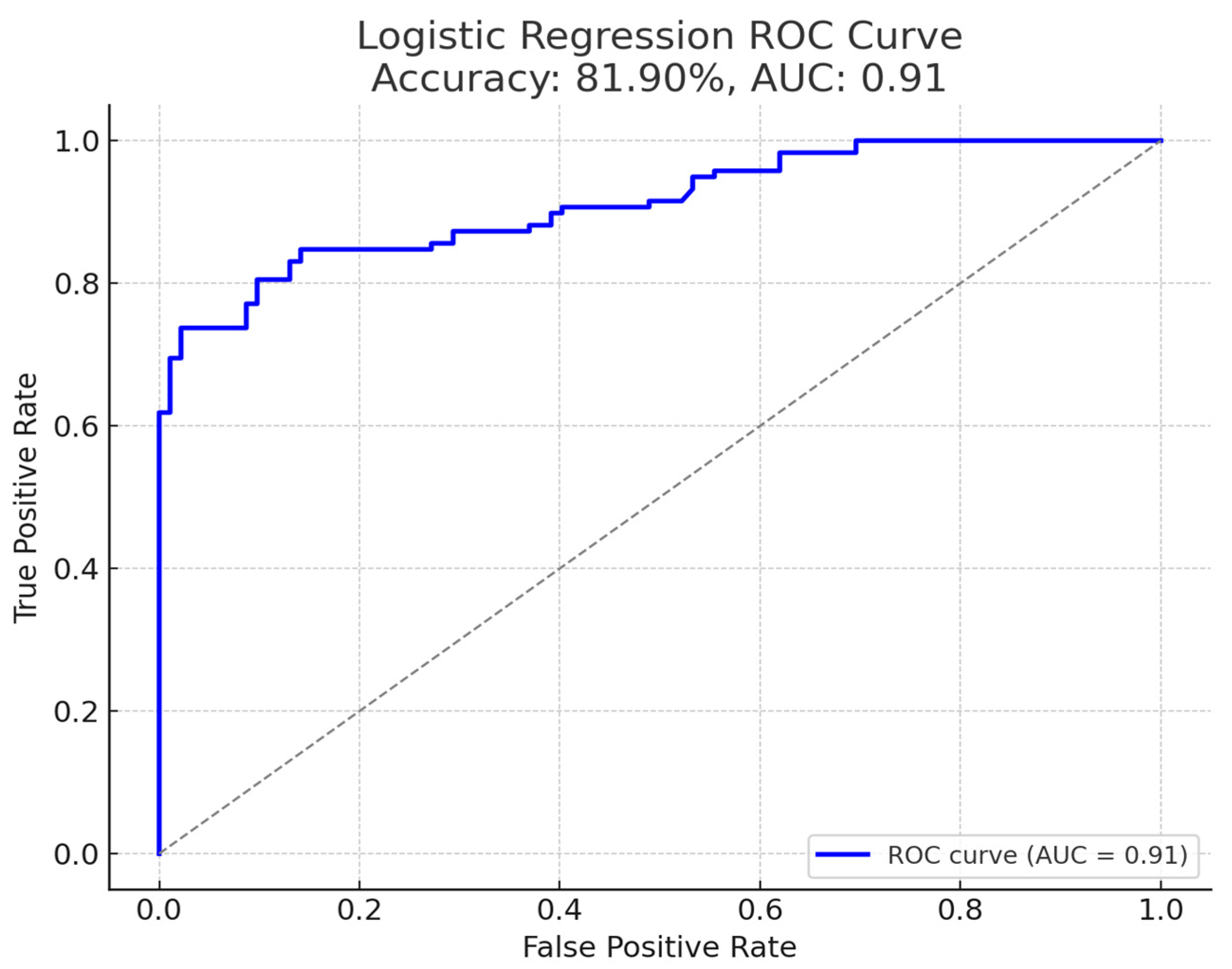

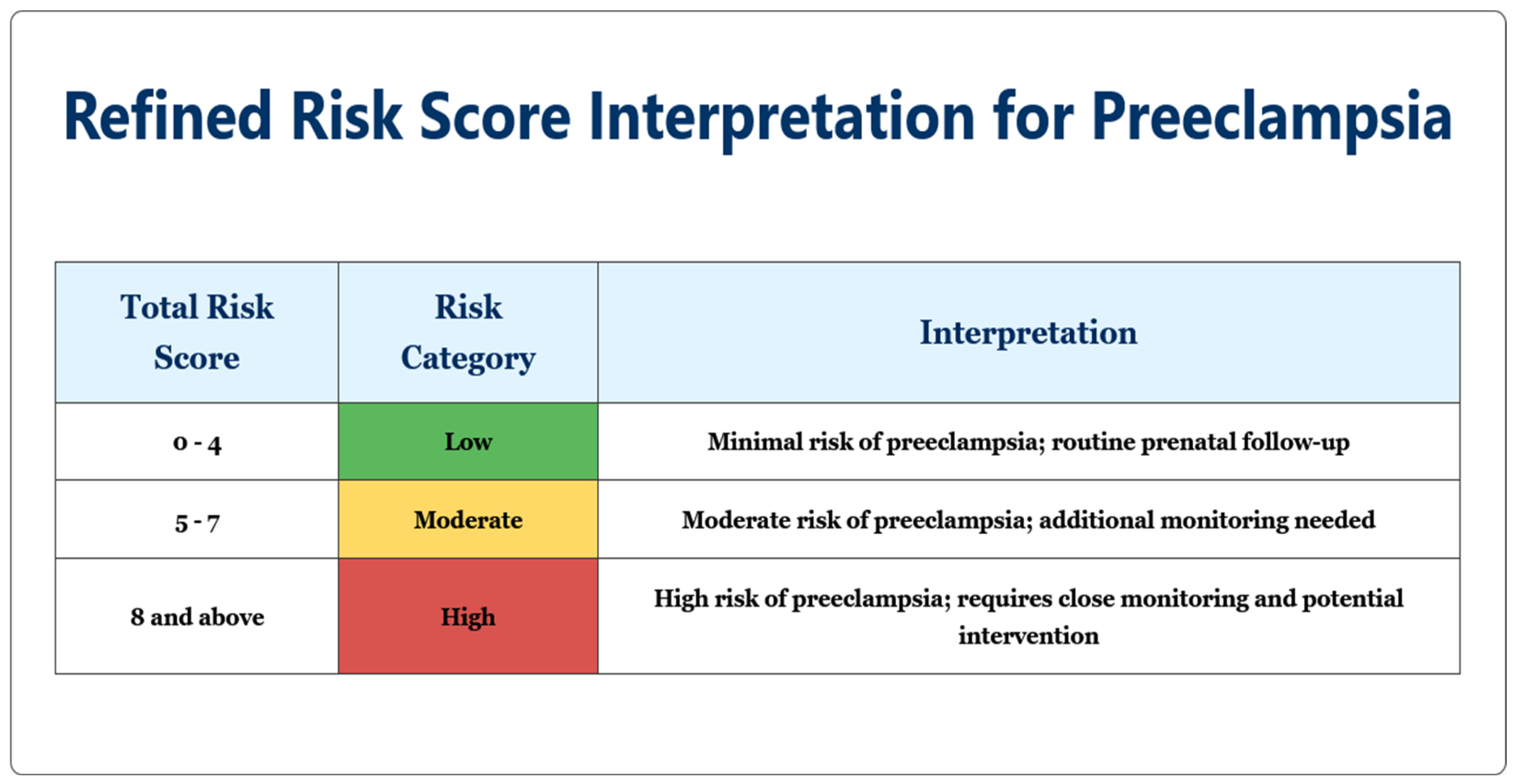

3.2. Risk Score Development

3.3. Maternal Outcomes by Risk Category

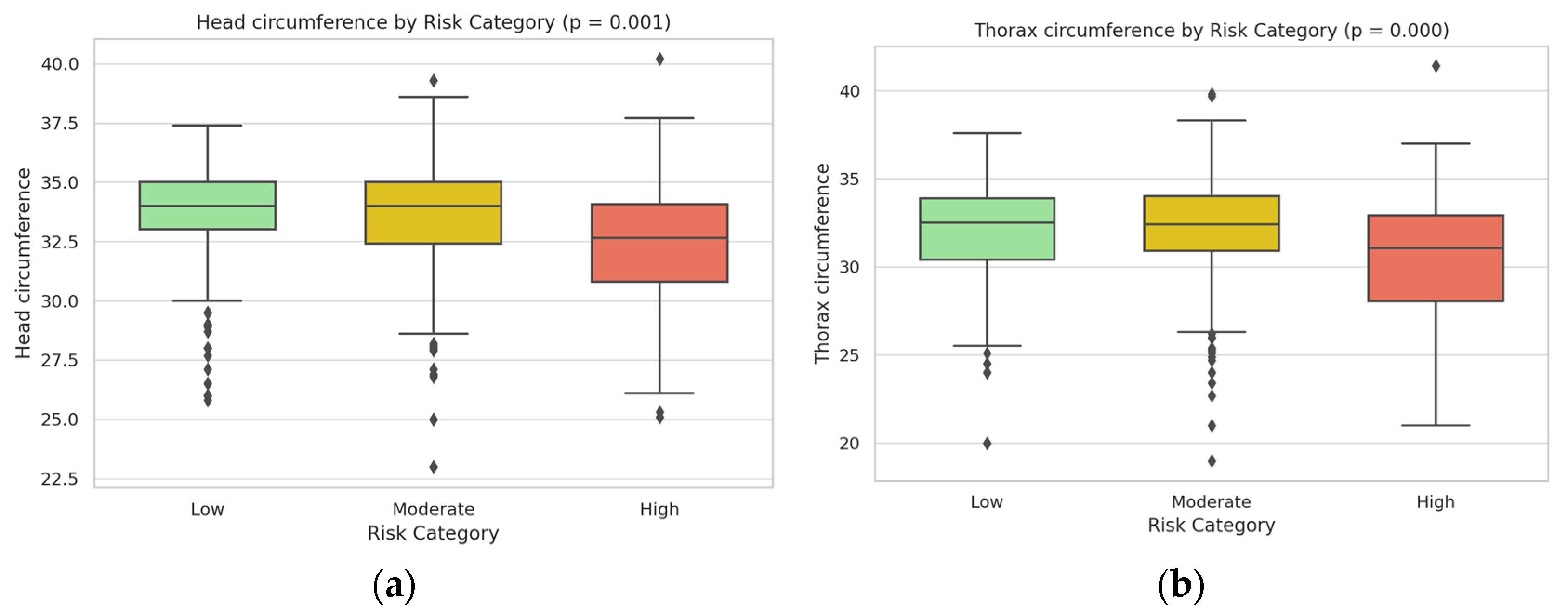

3.4. Neonatal Outcomes by Risk Category

3.5. Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Relevance and Utility of the Predictive Model

4.2. Implications for Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes

4.3. Socioeconomic Determinants and Healthcare Disparities

4.4. Implementation Framework for Clinical Practice

- Assessment timing: The risk assessment should be optimally performed during routine second-trimester visits (20–24 weeks), although risk scoring can further be applied to any gestational age on first presentation.

- Risk-stratified management protocols:

- Low-risk patients (0–4 points): Standard prenatal care with visits every 4–6 weeks, routine blood pressure monitoring, and standard education about pre-eclampsia warning signs.

- Moderate-risk patients (5–7 points): Increased surveillance with visits every 2–3 weeks, consideration of low-dose aspirin (although less effective when started after 16 weeks, some benefit may still be observed), and optional biomarker testing where available.

- High-risk patients (≥8 points): Intensive monitoring with weekly or biweekly visits, regular assessment of maternal organ function (liver enzymes, platelet counts, renal function), enhanced fetal surveillance with serial ultrasounds, and planning for possible early delivery after 37 weeks or sooner if complications develop.

- Resource allocation strategies:

- In low-resource settings: Focus advanced monitoring resources on high-risk patients while maintaining standard care for low-risk patients.

- In medium-resource settings: Implement tiered care model with intensity scaled to risk category.

- In high-resource settings: Integrate second-trimester risk score with first-trimester biomarker screening when available for comprehensive risk assessment.

- Healthcare provider education: Implement standardized training for clinicians on risk score calculation, interpretation, and management protocols.

- Patient education materials: Develop risk-appropriate educational resources, emphasizing different warning signs for each risk category.

- Follow-up protocol: Create structured follow-up schedules based on risk category, with clear escalation pathways when warning signs appear.

4.5. Recommendations for Clinical Practice and Future Research

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fox, R.; Kitt, J.; Leeson, P.; Aye, C.Y.; Lewandowski, A.J. Preeclampsia: Risk factors, diagnosis, management, and the cardiovascular impact on the offspring. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, R.A.; Das, J.K.; Ali, A.; Bhaumik, S.; Lassi, Z.S. Diagnosis and Management of Preeclampsia in Community Settings in Low and Middle-Income Countries. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibai, B.M. Etiology and management of preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, L.; Ahlberg, M.; Schmidt, J.; Lindqvist, P.G. Diagnostic criteria influence the incidence of preeclampsia: Trends over time in Sweden. Hypertension 2015, 65, 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.M.; Myatt, L.; Spong, C.Y.; Thom, E.A.; Hauth, J.C.; Leveno, K.J. Preeclampsia and the extracellular matrix: Pathway interactions contributing to long-term cardiovascular disease risk. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Verlohren, S.; Herraiz, I.; Lapaire, O.; Schlembach, D.; Zeisler, H.; Calda, P.; Sabria, J.; Markfeld-Erol, F.; Galindo, A.; Schoofs, K.; et al. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in different types of hypertensive pregnancy disorders and its prognostic potential in preeclamptic patients. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.J.; Maynard, S.E.; Qian, C.; Lim, K.H.; England, L.J.; Yu, K.F.; Schisterman, E.F.; Thadhani, R.; Sachs, B.P.; Epstein, F.H.; et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschat, A.A.; Galan, H.L.; Luo, J.; Turan, O.M.; Berg, C.; Harman, C.R. Screening for preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction with maternal blood pressure, uterine artery Doppler, and placental volume by 3D ultrasound in the first trimester. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 211, e1–e514. [Google Scholar]

- Chaemsaithong, P.; Seshadri, S.; Gray, K.J.; Keating, S.; Bainbridge, S.A.; Smith, G.N.; Whittle, W.; Kingdom, J.C. Potential clinical utility of first-trimester placental biomarkers for risk prediction of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, L.M.; García, R.G.; Ruiz, S.L.; Camacho, P.A.; Ospina, M.B.; Hurtado, I.C.; López-Jaramillo, P. Preeclampsia, a disease associated with inequality in maternal health care. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41622. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw, L.; Medley, N.; Darzi, A.J.; Richardson, M.; Habiba Garga, K.; Ongolo-Zogo, P. Health System and Community Level Interventions for Improving Antenatal Care Coverage and Health Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD010994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e215–e233. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, L.C.; Enye, S.; Seed, P.T.; Briley, A.L.; Poston, L.; Shennan, A.H. Adverse perinatal outcomes and risk factors for preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension: A prospective study. Hypertension 2008, 51, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Hypertension in Pregnancy: The Management of Hypertensive Disorders During Pregnancy. In National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance; RCOG Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.Y.; Wright, D.; Syngelaki, A.; Akolekar, R.; Cicero, S.; Janga, D.; Singh, M.; Greco, E.; Wright, A.; Maclagan, K.; et al. Comparison of Diagnostic Accuracy of Early Screening for Pre-Eclampsia by NICE Guidelines and a Method Combining Maternal Factors and Biomarkers: Results of SPREE. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolnik, D.L.; Wright, D.; Poon, L.C.; O’Gorman, N.; Syngelaki, A.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Akolekar, R.; Cicero, S.; Janga, D.; Singh, M.; et al. Aspirin versus placebo in pregnancies at high risk for preterm preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velegrakis, A.; Kouvidi, E.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Sifakis, S. Predictive Value of the sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio in Women with Suspected Preeclampsia: An Update (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 52, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.; Romero, R.; Nien, J.K.; Gomez, R.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Medina, L.; Edwin, S.; Hassan, S.; Carstens, M.; et al. Identification of Patients at Risk for Early Onset and/or Severe Preeclampsia with the Use of Uterine Artery Doppler Velocimetry and Placental Growth Factor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 326.e1–326.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, L.C.; Syngelaki, A.; Akolekar, R.; Lai, J.; Nicolaides, K.H. Combined screening for preeclampsia and small for gestational age at 11–13 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 33, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ødegård, R.A.; Vatten, L.J.; Nilsen, S.T.; Salvesen, K.A.; Austgulen, R. Preeclampsia and fetal growth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 96, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Goh, P.S.; Allison, B.J.; Lees, C.; Kametas, N.A. A prospective study of fetal and neonatal outcomes in women with preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 23, 452–456. [Google Scholar]

- Luealon, P.; Phupong, V. Risk Factors of Preeclampsia in Thai Women. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2010, 93, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q.; Koene, R.J.; Yancy, C.W.; Macones, G.A.; Cahill, A.G.; Roberson, J.; Young, O.M. Preeclampsia and primary prevention strategies: A review. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 141, 103154. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, J. Preventive strategies for preeclampsia: An expert’s perspective. JAMA 2021, 326, 219–220. [Google Scholar]

- Roberge, S.; Nicolaides, K.; Demers, S.; Hyett, J.; Chaillet, N.; Bujold, E. Prevention of preeclampsia by low-molecular-weight heparin in addition to aspirin: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 40, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.T.; Whitlock, E.P.; O’Connor, E.; Senger, C.A.; Thompson, J.H.; Rowland, M.G. Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duley, L.; Meher, S.; Abalos, E. Management of pre-eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 6, CD001980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Dalziel, S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 3, CD004454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-Eclampsia Group (n = 350) | Control Group (n = 350) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| <30 | 92 (26.3%) | 169 (48.3%) | 0.0003 |

| 30–35 | 163 (46.6%) | 146 (41.7%) | 0.182 |

| >35 | 95 (27.1%) | 35 (10.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 36.2 ± 2.8 | 39.1 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 198 (56.6%) | 142 (40.6%) | 0.0002 |

| Multiparous | 152 (43.4%) | 208 (59.4%) | 0.0002 |

| Pre-existing conditions | |||

| Chronic hypertension | 87 (24.9%) | 14 (4.0%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (18.0%) | 21 (6.0%) | 0.003 |

| Education level | |||

| Below high school | 126 (36.0%) | 63 (18.0%) | 0.0007 |

| High school or above | 224 (64.0%) | 287 (82.0%) | 0.0007 |

| Health insurance | |||

| Yes | 263 (75.1%) | 312 (89.1%) | 0.0016 |

| No | 87 (24.9%) | 38 (10.9%) | 0.0016 |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 5.2 | 24.8 ± 4.1 | 0.0023 |

| Outcome | Low Risk (n = 382) | Moderate Risk (n = 196) | High Risk (n = 122) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe pre-eclampsia | 9 (2.4%) | 48 (24.5%) | 84 (68.9%) | 0.0004 |

| Eclampsia | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.5%) | 15 (12.3%) | <0.0001 |

| HELLP syndrome | 2 (0.5%) | 7 (3.6%) | 11 (8.7%) | 0.0013 |

| ICU admission | 5 (1.3%) | 12 (6.1%) | 23 (18.9%) | 0.0002 |

| Emergency cesarean delivery | 76 (19.9%) | 72 (36.7%) | 87 (71.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 15 (3.9%) | 17 (8.7%) | 26 (21.3%) | 0.0007 |

| Antihypertensive therapy required | 14 (3.7%) | 63 (32.1%) | 103 (84.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Mean systolic BP (mmHg) | 123.4 ± 10.2 | 142.6 ± 15.8 | 157.8 ± 18.3 | 0.0003 |

| Mean diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78.2 ± 7.4 | 88.9 ± 10.2 | 98.5 ± 11.7 | 0.0008 |

| Outcome | Low Risk (n = 382) | Moderate Risk (n = 196) | High Risk (n = 122) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (g) | 3284 ± 432 | 3076 ± 526 | 2798 ± 612 | 0.0003 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 21 (5.5%) | 29 (14.8%) | 42 (34.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34.2 ± 1.8 | 33.4 ± 2.1 | 31.9 ± 2.4 | 0.0017 |

| Thorax circumference (cm) | 33.1 ± 1.6 | 32.3 ± 1.9 | 30.4 ± 2.2 | 0.0009 |

| Fetal length (cm) | 50.2 ± 2.3 | 48.9 ± 2.7 | 46.3 ± 3.2 | 0.0002 |

| APGAR score (1 min) | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 7.1 ± 1.4 | 0.0015 |

| APGAR score (5 min) | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 1.2 | 0.0023 |

| NICU admission | 18 (4.7%) | 26 (13.3%) | 37 (30.3%) | 0.0006 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | 28 (7.3%) | 42 (21.4%) | 61 (50.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 12 (3.1%) | 19 (9.7%) | 28 (23.0%) | 0.0018 |

| Subgroup | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 74.4% | 97.8% | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | <0.0001 |

| By parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 79.2% | 96.5% | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) | <0.0001 |

| Multiparous | 68.7% | 94.2% | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | <0.0001 |

| By age | ||||

| <35 years | 76.3% | 95.8% | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | <0.0001 |

| ≥35 years | 71.5% | 93.6% | 0.89 (0.85–0.93) | 0.0002 |

| By education | ||||

| Below high school | 80.1% | 94.5% | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | 0.0003 |

| High school or above | 72.2% | 96.1% | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.0005 |

| By insurance status | ||||

| Insured | 73.8% | 96.8% | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.0002 |

| Uninsured | 81.2% | 92.3% | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | 0.0015 |

| Model |

Timing (Trimester) | Key Components | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | 2nd | Clinical factors | 0.91 | 74.4% | 97.8% | No specialized tests needed | Moderate sensitivity |

| NICE Guidelines [15] | 1st | Maternal history | 0.77 | 89% | 61% | Simple, no tests | Low specificity |

| FMF Bayes [16] | 1st | Maternal history, MAP, UTPI, PAPP-A, PlGF | 0.95 | 89% | 90% | Highest accuracy | Requires specialized tests |

| ASPRE Trial [17] | 1st | Maternal history, MAP, UTPI, PAPP-A, PlGF | 0.92 | 76% | 91% | Validated in large trial | Requires specialized tests |

| sFlt-1/PlGF [18] | Any | Blood biomarkers | 0.89 | 82% | 95% | Good for rule-out | Expensive biomarker test |

| Espinoza et al. [19] | 2nd | Doppler + maternal history | 0.85 | 72% | 83% | Good mid-pregnancy tool | Requires Doppler ultrasound |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buciu, V.B.; Novacescu, D.; Zara, F.; Șerban, D.M.; Tomescu, L.; Ciurescu, S.; Olariu, S.; Rakitovan, M.; Armega-Anghelescu, A.; Cindrea, A.C.; et al. Development of a Risk Score for the Prediction and Management of Pre-Eclampsia in Low-Resource Settings. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103398

Buciu VB, Novacescu D, Zara F, Șerban DM, Tomescu L, Ciurescu S, Olariu S, Rakitovan M, Armega-Anghelescu A, Cindrea AC, et al. Development of a Risk Score for the Prediction and Management of Pre-Eclampsia in Low-Resource Settings. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103398

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuciu, Victor Bogdan, Dorin Novacescu, Flavia Zara, Denis Mihai Șerban, Larisa Tomescu, Sebastian Ciurescu, Sebastian Olariu, Marina Rakitovan, Antonia Armega-Anghelescu, Alexandu Cristian Cindrea, and et al. 2025. "Development of a Risk Score for the Prediction and Management of Pre-Eclampsia in Low-Resource Settings" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103398

APA StyleBuciu, V. B., Novacescu, D., Zara, F., Șerban, D. M., Tomescu, L., Ciurescu, S., Olariu, S., Rakitovan, M., Armega-Anghelescu, A., Cindrea, A. C., Ionac, M., & Chiriac, V.-D. (2025). Development of a Risk Score for the Prediction and Management of Pre-Eclampsia in Low-Resource Settings. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103398