Endoscopic Use of N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate in Refractory Pancreatic Duct Leak and Cystic Duct Leak: Is It Really a Last Resort?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Case Reports

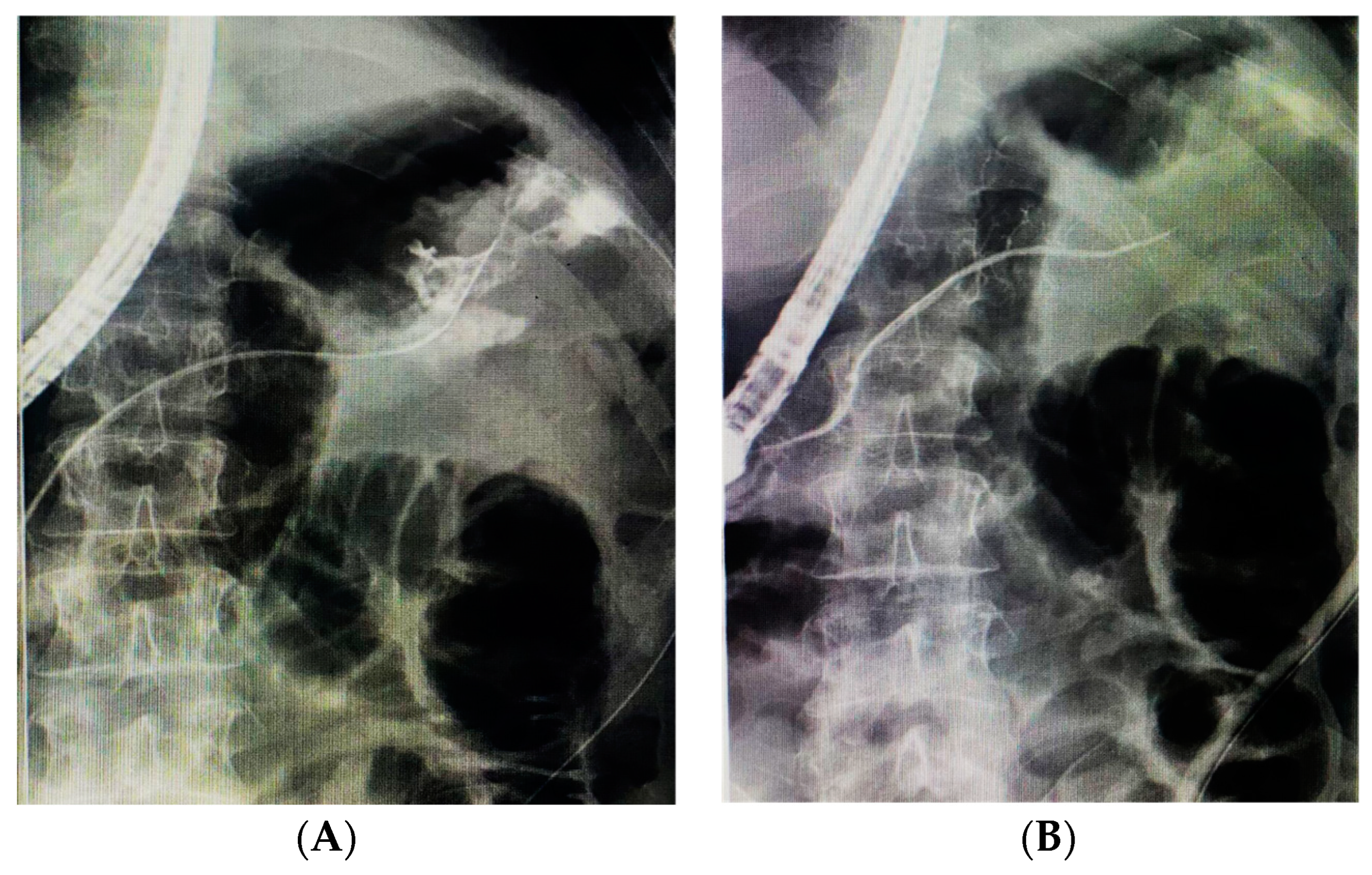

3.1. Pancreatic Duct Leak

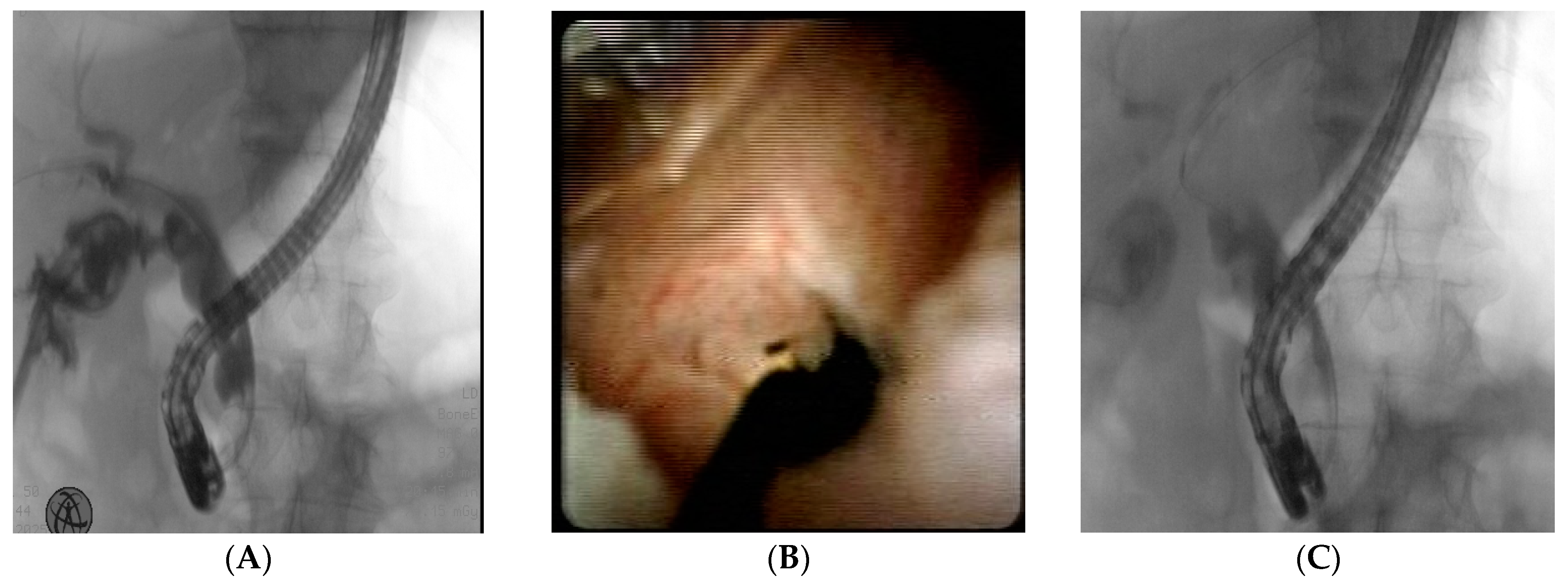

3.2. Cystic Duct Leak

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NBCA | N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate |

| ERCP | Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography |

| PD | Pancreatic duct |

| LC | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| EST | Endoscopic sphincterotomy |

References

- Gralnek, I.M.; Camus Duboc, M.; Garcia-Pagan, J.C.; Fuccio, L.; Karstensen, J.G.; Hucl, T.; Jovanovic, I.; Awadie, H.; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Tantau, M.; et al. Endoscopic Diagnosis and Management of Esophagogastric Variceal Hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 1094–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, R.; Binmoeller, K.F. Cyanoacrylate Applications in the GI Tract. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 77, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidani, N.; Hirotsune, N. NBCA: Basic Knowledge. J. Neuroendovasc. Ther. 2025, 19, 2024-0055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.; Kozarek, R. Management of Pancreatic Ductal Leaks and Fistulae. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, F.; Shen, M.; Tian, R.; Shi, C.J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.X.; Hu, J.; Wang, M.; Qin, R.Y. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Comparing Three Techniques for Pancreatic Remnant Closure Following Distal Pancreatectomy. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise Unger, S.; Glick, G.L.; Landeros, M. Cystic Duct Leak after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. A Multi-Institutional Study. Surg. Endosc. 1996, 10, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de’Angelis, N.; Catena, F.; Memeo, R.; Coccolini, F.; Martínez-Pérez, A.; Romeo, O.M.; De Simone, B.; Di Saverio, S.; Brustia, R.; Rhaiem, R.; et al. 2020 WSES Guidelines for the Detection and Management of Bile Duct Injury during Cholecystectomy. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2021, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ödemiş, B.; Durak, M.B.; Atay, A.; Başpınar, B.; Erdoğan, Ç. A Step-Up Approach Using Alternative Endoscopic Modalities Is an Effective Strategy for Postoperative and Traumatic Pancreatic Duct Disruption. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 3745–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albasini, J.L.; Aledo, V.S.; Dexter, S.P.; Marton, J.; Martin, I.G.; McMahon, M.J. Bile Leakage Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 1995, 9, 1274–1278. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8629208/ (accessed on 25 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, H.; Papachristou, G.I. Endoscopic Treatment for Post-Cholecystectomy Bile Leaks: Update and Recent Advances. Ann. Gastroenterol. Q. Publ. Hell. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2011, 24, 161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Nagra, N.; Klair, J.S.; Jayaraj, M.; Murali, A.R.; Singh, D.; Law, J.; Larsen, M.; Irani, S.; Kozarek, R.; Ross, A.; et al. Biliary Sphincterotomy Alone versus Biliary Stent with or without Biliary Sphincterotomy for the Management of Post-Cholecystectomy Bile Leak: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. 2022, 40, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, N.A.; Kotwal, V.; Sarr, M.G.; Swaroop Vege, S. Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome: Endoscopic Stent or Surgeon’s Knife? Pancreas 2015, 44, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoellhammer, H.F.; Fong, Y.; Gagandeep, S. Techniques for Prevention of Pancreatic Leak after Pancreatectomy. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2014, 3, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Papachristou, G.I.; Slivka, A.; Easler, J.J.; Chennat, J.; Malin, J.; Herman, J.B.; Laique, S.N.; Hayat, U.; Ooi, Y.S.; et al. Endotherapy Is Effective for Pancreatic Ductal Disruption: A Dual Center Experience. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 278–283. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26774205/ (accessed on 22 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Strasberg, S.M.; Hertl, M.; Soper, N.J. An Analysis of the Problem of Biliary Injury during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1995, 180, 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, T.H.; Poterucha, J.J. Insertion and Removal of Covered Expandable Metal Stents for Closure of Complex Biliary Leaks. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 4, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaleh, M.; Sundaram, V.; Condron, S.L.; De La Rue, S.A.; Hall, J.D.; Tokar, J.; Friel, C.M.; Foley, E.F.; Adams, R.B.; Yeaton, P. Temporary Placement of Covered Self-Expandable Metallic Stents in Patients with Biliary Leak: Midterm Evaluation of a Pilot Study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 66, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seewald, S.; Brand, B.; Groth, S.; Omar, S.; Mendoza, G.; Seitz, U.; Yasuda, I.; Xikun, H.; Nam, V.C.; Xu, H.; et al. Endoscopic Sealing of Pancreatic Fistula by Using N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2004, 59, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutignani, M.; Tringali, A.; Khodadadian, E.; Petruzziello, L.; Spada, C.; Spera, G.; Familiari, P.; Costamagna, G. External Pancreatic Fistulas Resistant to Conventional Endoscopic Therapy: Endoscopic Closure With N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate (Glubran 2). Endoscopy 2004, 36, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labori, K.J.; Trondsen, E.; Buanes, T.; Hauge, T. Endoscopic Sealing of Pancreatic Fistulas: Four Case Reports and Review of the Literature. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahakian, A.B.; Jayaram, P.; Marx, M.V.; Matsushima, K.; Park, C.; Buxbaum, J.L. Metallic Coil and N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate for Closure of Pancreatic Duct Leak (with Video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 87, 1122–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutignani, M.; Dokas, S.; Tringali, A.; Forti, E.; Pugliese, F.; Cintolo, M.; Manta, R.; Dioscoridi, L. Pancreatic Leaks and Fistulae: An Endoscopy-Oriented Classification. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2648–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seewald, S.; Groth, S.; Sriram, P.V.J.; Xikun, H.; Akaraviputh, T.; Mendoza, G.; Brand, B.; Seitz, U.; Thonke, F.; Soehendra, N. Endoscopic Treatment of Biliary Leakage with N-Butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2002, 56, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, G.; Jairath, V.; Reynolds, M.; Shidrawi, R.G. Endoscopic Glue Injection for Persistent Biliary Leakage. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2009, 70, 1279–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahaibi, A.A.; Alnaamani, K.; Alkindi, A.; Qarshoubi, I.A. A Novel Endoscopic Treatment of Major Bile Duct Leak. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 5, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, E.K.; Najarian, K.E.; Vecchio, J.A.; Moses, P.L. Endoscopic Occlusion of Cystic Duct Using N -Butyl Cyanoacrylate for Postoperative Bile Leakage. Dig. Endosc. 2010, 22, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 51 | 38 | 63 |

| Sex | M | M | F |

| Etiology | Open splenectomy (car accident) | Open splenectomy (stab wounds) | Open splenectomy (accident at work) |

| Location | Tail (IT) | Tail (IT) | Tail (IT) |

| Days after the previous unsuccessful Endoscopic treatment | 14 | N/A | 10 |

| NBCA injected | 1 mL | 1 mL | 1 mL |

| Outcome | Healing of the fistula | Healing of the fistula | Healing of the fistula |

| Complications | None | None | None |

| Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66 | 49 | 79 |

| Sex | F | M | M |

| Etiology | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Open cholecystectomy |

| Location | Cystic Duct (Type A sec. Strasberg) | Cystic Duct (Type A sec. Strasberg) | Cystic Duct (Type A sec. Strasberg) |

| Days after previous unsuccessful endoscopic treatment | 10 | 6 | 3 |

| NBCA injected (mL) | 1 mL | 2 mL | 2 mL |

| Outcome | Healing of the fistula | Healing of the fistula | Healing of the fistula |

| Complications | None | None | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gagliardi, M.; Soldaini, C.; Sica, M.; Abbatiello, C.; Fusco, M.; Fimiano, F.; Pontillo, G.; Donnarumma, E.; Puzziello, A.; Zulli, C. Endoscopic Use of N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate in Refractory Pancreatic Duct Leak and Cystic Duct Leak: Is It Really a Last Resort? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103362

Gagliardi M, Soldaini C, Sica M, Abbatiello C, Fusco M, Fimiano F, Pontillo G, Donnarumma E, Puzziello A, Zulli C. Endoscopic Use of N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate in Refractory Pancreatic Duct Leak and Cystic Duct Leak: Is It Really a Last Resort? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103362

Chicago/Turabian StyleGagliardi, Mario, Carlo Soldaini, Mariano Sica, Carmela Abbatiello, Michele Fusco, Federica Fimiano, Giuseppina Pontillo, Elio Donnarumma, Alessandro Puzziello, and Claudio Zulli. 2025. "Endoscopic Use of N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate in Refractory Pancreatic Duct Leak and Cystic Duct Leak: Is It Really a Last Resort?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103362

APA StyleGagliardi, M., Soldaini, C., Sica, M., Abbatiello, C., Fusco, M., Fimiano, F., Pontillo, G., Donnarumma, E., Puzziello, A., & Zulli, C. (2025). Endoscopic Use of N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate in Refractory Pancreatic Duct Leak and Cystic Duct Leak: Is It Really a Last Resort? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103362