Influence of Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease History on the Use of Immunosuppressants, Biological Agents and Surgery in Patients with Pediatric-Onset of the Disease in the Era of Biological Therapies. Results from the ENEIDA Registry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population, Data Collection, and Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

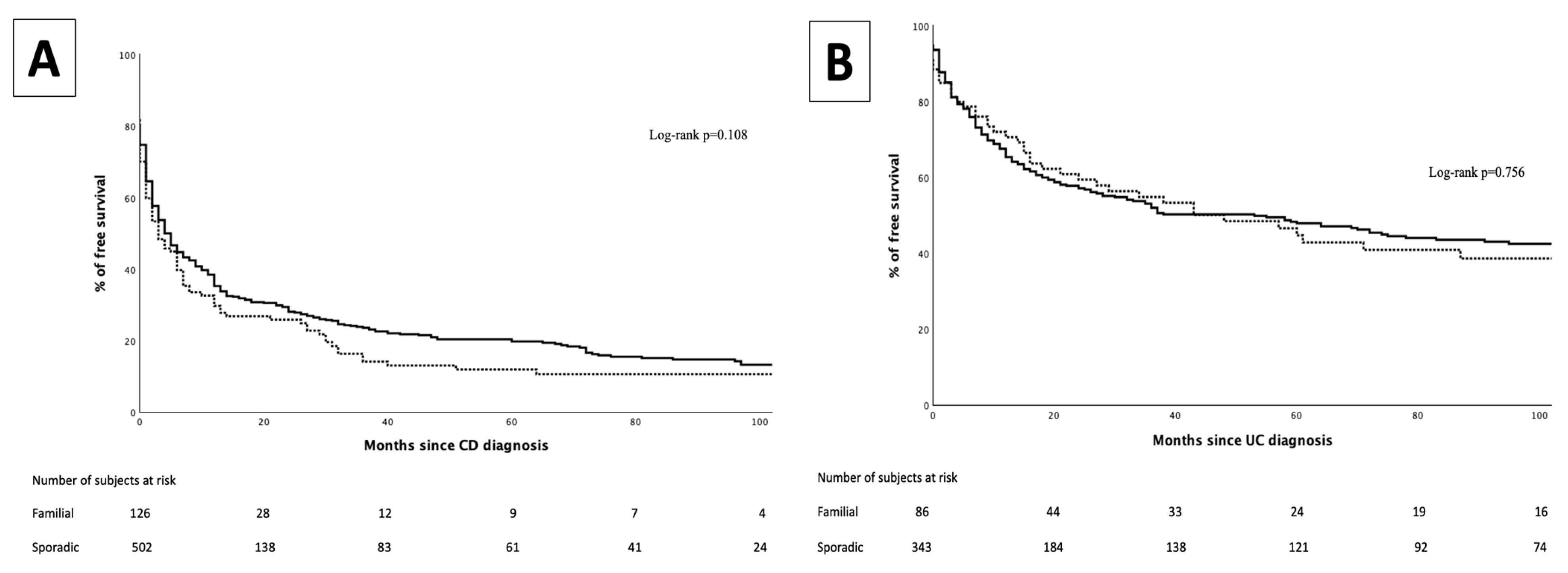

3.1. Immunomodulators

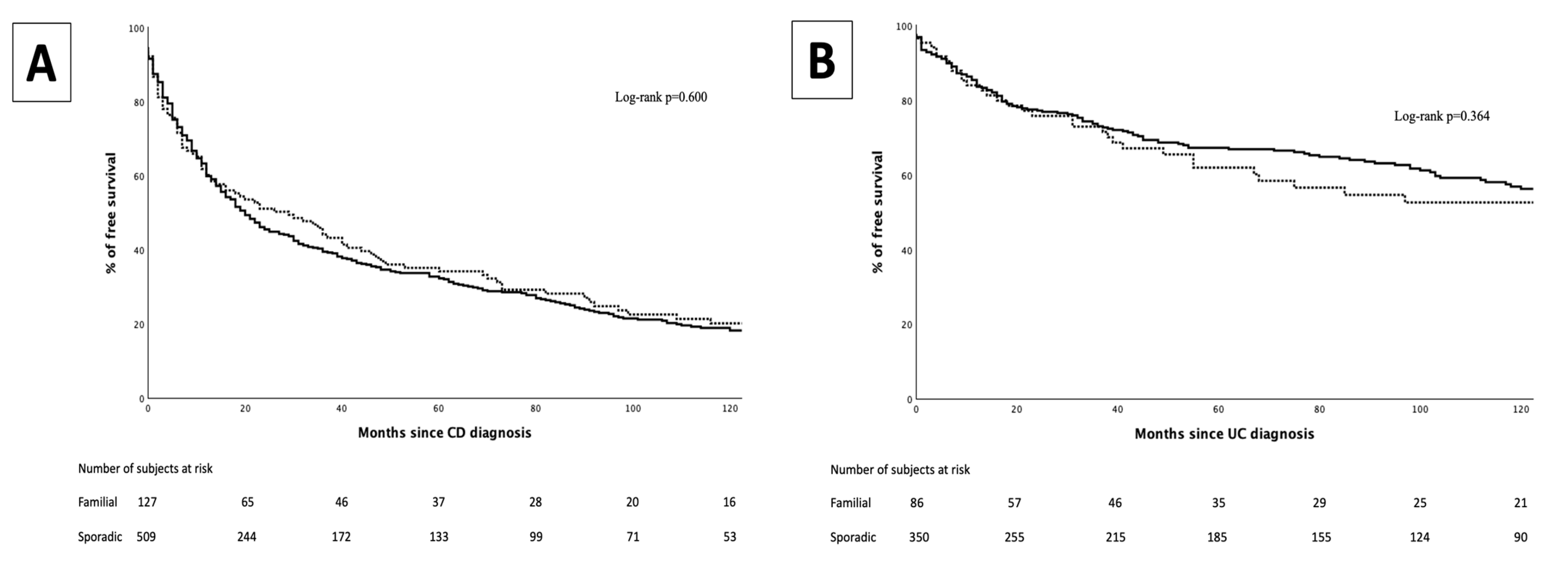

3.2. Biological Therapy

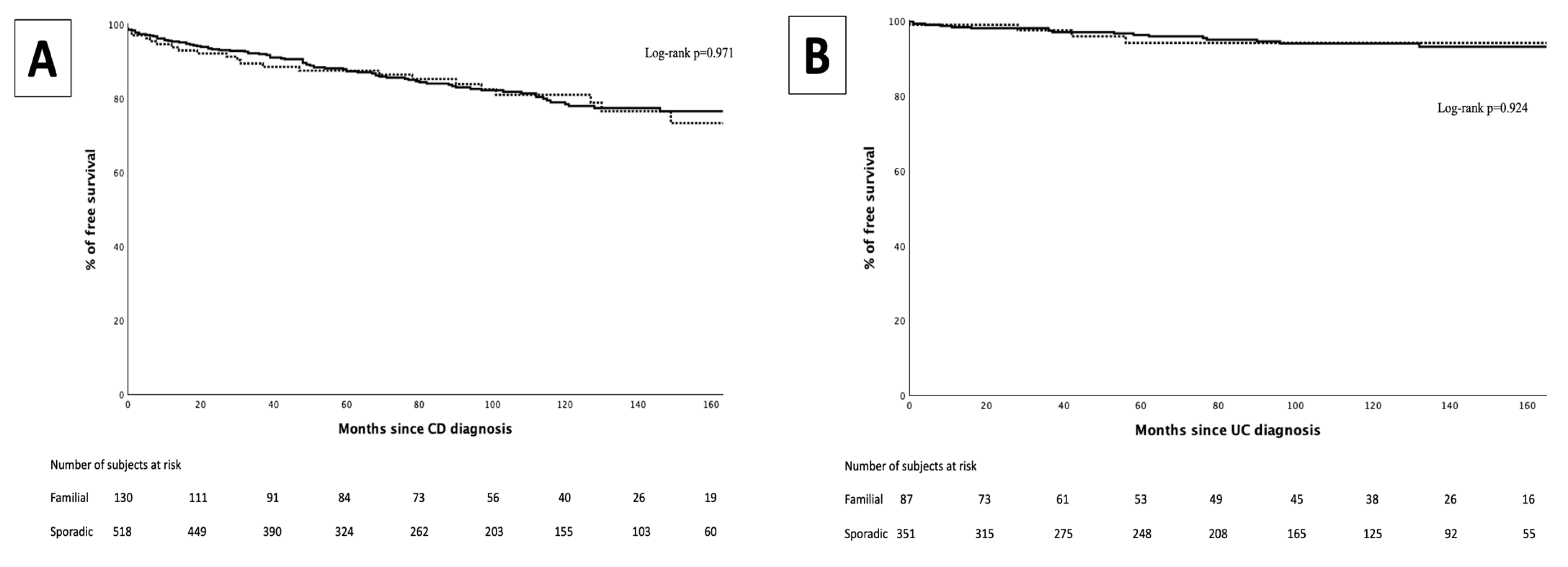

3.3. Intestinal Surgeries

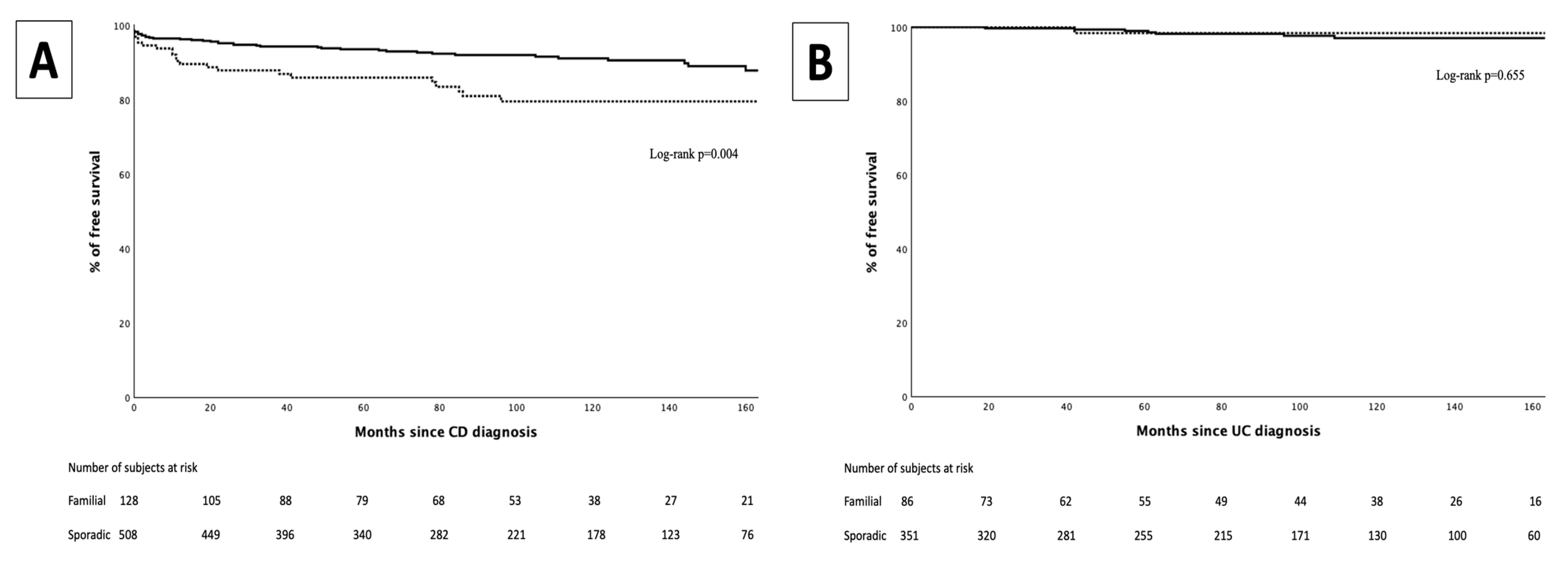

3.4. Perianal Surgeries

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| FF | Familial forms |

| SF | Sporadic forms |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| IMM | Immunomodulators |

| GETECCU | Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis |

References

- Kaplan, G.G.; Windsor, J.W. The Four Epidemiological Stages in the Global Evolution of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuenzig, M.E.; Fung, S.G.; Marderfeld, L.; Mak, J.W.Y.; Kaplan, G.G.; Ng, S.C.; Wilson, D.C.; Cameron, F.; Henderson, P.; Kotze, P.G.; et al. Twenty-First Century Trends in the Global Epidemiology of Pediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1147–1159.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.N.; Appleton, L.; Gearry, R.B.; Day, A.S. Rising Incidence of Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canterbury, New Zealand, 1996–2015. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, e45–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.J.; Barakat, F.M.; Barnes, C.; Coelho, T.A.F.; Batra, A.; Afzal, N.A.; Beattie, R.M. Incidence and Prevalence of Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Continues to Increase in the South of England. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, E20–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Bernstein, C.N.; Bitton, A.; Carroll, M.W.; Singh, H.; Otley, A.R.; Vutcovici, M.; El-Matary, W.; Nguyen, G.C.; Griffiths, A.M.; et al. Trends in Epidemiology of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: Distributed Network Analysis of Multiple Population-Based Provincial Health Administrative Databases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1120–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussaini, A.; El Mouzan, M.; Hasosah, M.; Al-Mehaidib, A.; Alsaleem, K.; Saadah, O.I.; Al-Edreesi, M. Clinical Pattern of Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Saudi Arabia: A Multicenter National Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowitz, S.M. The Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clues to Pathogenesis? Front. Pediatr. 2023, 10, 1103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Sabino, J.; Frias-Gomes, C.; Hillenbrand, C.M.; Soudant, C.; Axelrad, J.E.; Shah, S.C.; Ribeiro-Mourão, F.; Lambin, T.; Peter, I.; et al. Early Life Exposures and the Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, F.T.; Andersen, V.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Jess, T. Familial Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study 1977-2011. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amre, D.K.; Lambrette, P.; Law, L.; Krupoves, A.; Chotard, V.; Costea, F.; Grimard, G.; Israel, D.; Mack, D.; Seidman, E.G. Investigating the Hygiene Hypothesis as a Risk Factor in Pediatric Onset Crohn’s Disease: A Case-Control Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, G.; Hassall, E. Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Paediatric Population. J. Adv. Nurs. 1992, 17, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Bostrom, A.G.; Ph, D.; Kirschner, B.S.; Cohen, A.; Abramson, O.; Ferry, G.D.; Gold, B.D.; Winter, H.S.; Baldassano, R.N.; et al. Presentation and disease course in early- compared to later-onset pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 103, 2092–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, T.; Birnbaum, A.; Pal, D.K.; Pittman, N.; Ceballos, C.; Leleiko, N.S.; Benkov, K. Distinct Phenotype of Early Childhood Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, V. Epidemiology of IBD during the Twentieth Century: An Integrated View. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2004, 18, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-de-Carpi, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Ramos, E.; Jiménez, S.; Martínez-Gómez, M.J.; Medina, E.; Serrano, J.; Ricart, E.; Sánchez-Valverde, F.; Peña-Quintana, L.; et al. Increasing Incidence of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain (1996-2009): The SPIRIT Registry. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghione, S.; Sarter, H.; Fumery, M.; Armengol-Debeir, L.; Savoye, G.; Ley, D.; Spyckerelle, C.; Pariente, B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Turck, D.; et al. Dramatic Increase in Incidence of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease (1988–2011): A Population-Based Study of French Adolescents. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C.J.; Henderson, P.; Jones, G.R.; Lees, C.W.; Wilson, D.C. Paediatric Patients (Less Than Age of 17 Years) Account for Less Than 1.5% of All Prevalent Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cases. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, L.; Weersma, R.K.; Dijkstra, G.; Van Der Steege, G.; Benninga, M.A.; Nolte, I.M.; Taminiau, J.A.J.M.; Hommes, D.W.; Stokkers, P.C.F. Genetic Susceptibility Has a More Important Role in Pediatric-Onset Crohn’s Disease than in Adult-Onset Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 13, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duricova, D.; Sarter, H.; Savoye, G.; Leroyer, A.; Pariente, B.; Armengol-Debeir, L.; Bouguen, G.; Ley, D.; Turck, D.; Templier, C.; et al. Impact of Extra-Intestinal Manifestations at Diagnosis on Disease Outcome in Pediatric- and Elderly-Onset Crohn′s Disease: A French Population-Based Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, M.B.; Kirschner, B.S.; Gold, B.D.; Ferry, G.; Baldassano, R.; Cohen, S.A.; Winter, H.S.; Fain, P.; King, C.; Smith, T.; et al. Children with Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Analysis of a Pediatric IBD Consortium Registry. J. Pediatr. 2005, 146, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishige, T.; Tomomasa, T.; Takebayashi, T.; Asakura, K.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, T.; Miyazawa, R.; Arakawa, H. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children: Epidemiological Analysis of the Nationwide IBD Registry in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Garre, A.; Ricart, E.; Iglesias-Flores, E.; Taxonera, C.; Domènech, E.; Gisbert, J.P.; Mañosa, M.; Vera Mendoza, I.; Mínguez, M.; et al. Differences between Childhood- and Adulthood-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The CAROUSEL Study from GETECCU. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, A.; Griffiths, A.; Markowitz, J.; Wilson, D.C.; Turner, D.; Russell, R.K.; Fell, J.; Ruemmele, F.M.; Walters, T.; Sherlock, M.; et al. Pediatric Modification of the Montreal Classification for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Paris Classification. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, M.; Lionetti, P.; Barabino, A.; Guariso, G.; Costa, S.; Fontana, M.; Romano, C.; Lombardi, G.; Miele, E.; Alvisi, P.; et al. Phenotype and Disease Course of Early-Onset Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Papadatou, B.; Baldassare, M.; Balli, F.; Barabino, A.; Barbera, C.; Barca, S.; Barera, G.; Bascietto, F.; Canani, R.B.; et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adolescents in Italy: Data from the Pediatric National IBD Register (1996–2003). Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arai, K. Very Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Challenging Field for Pediatric Gastroenterologists. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2020, 23, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, E.S.; Panayiotou, J.; Pachoula, J.; Constantinidou, C.; Polyzos, A.; Zellos, A.; Lagona, E.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Syriopoulou, V.P. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children: The Role of a Positive Family History. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 22, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawi, F.; Assa, A.; Eliakim, R.; Mozer-Glassberg, Y.; Nachmias Friedler, V.; Niv, Y.; Rosenbach, Y.; Silbermintz, A.; Zevit, N.; Shamir, R. The Natural History of Pediatric-Onset IBD-Unclassified and Prediction of Crohn’s Disease Reclassification: A 27-Year Study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower-Rousseau, C.; Dauchet, L.; Vernier-Massouille, G.; Tilloy, E.; Brazier, F.; Merle, V.; Dupas, J.L.; Savoye, G.; Baldé, M.; Marti, R.; et al. The Natural History of Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 2080–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, M.; Slavick, A.; Amir, A.; Ben-Tov, A.; Moran-Lev, H.; Weintraub, Y.; Anafy, A.; Cohen, S.; Yerushalmy-Feler, A. Increasing Rate of a Positive Family History of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) in Pediatric IBD Patients. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, R.A.; Lewis, L.G.; Warner, B.W. Predicting the Need for Colectomy in Pediatric Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2000, 4, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloi, M.; D’Arcangelo, G.; Capponi, M.; Nuti, F.; Vassallo, F.; Civitelli, F.; Oliva, S.; Pagliaro, G.; Cucchiara, S. Managing Paediatric Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis According to the 2011 ECCO-ESPGHAN Guidelines: Efficacy of Infliximab as a Rescue Therapy. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buczyńska, A.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U. Prognostic Factors of Biologic Therapy in Pediatric IBD. Children 2022, 9, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley-Quon, L.I.; Jen, H.C.; Ziring, D.A.; Gupta, N.; Kirschner, B.S.; Ferry, G.D.; Cohen, S.A.; Winter, H.S.; Heyman, M.B.; Gold, B.D.; et al. Predictors of Proctocolectomy in Children with Ulcerative Colitis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, M.; D’Arcangelo, G.; Pofi, F.; Vassallo, F.; Rizzo, V.; Nuti, F.; Di Nardo, G.; Pierdomenico, M.; Viola, F.; Cucchiara, S. Presenting Features and Disease Course of Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, e509–e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawi, F.; Assa, A.; Eliakim, R.; Mozer-Glassberg, Y.; Nachmias-Friedler, V.; Niv, Y.; Rosenbach, Y.; Silbermintz, A.; Zevit, N.; Shamir, R. Risk of Colectomy in Patients with Pediatric-Onset Ulcerative Colitis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Muñoza, C.; Calafat, M.; Gisbert, J.P.; Iglesias, E.; Mínguez, M.; Sicilia, B.; Aceituno, M.; Gomollón, F.; Calvet, X.; Ricart, E.; et al. Influence of Familial Forms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease on the Use of Immunosuppressants, Biological Agents, and Surgery in the Era of Biological Therapies. Results from the ENEIDA Project. Postgrad. Med. J. 2024, 100, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabana, Y.; Panés, J.; Nos, P.; Gomollón, F.; Esteve, M.; García-Sánchez, V.; Gisbert, J.P.; Barreiro-de-Acosta, M.; Domènech, E. The ENEIDA Registry (Nationwide Study on Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Inflammatory Bowel Disease) by GETECCU: Design, Monitoring and Functions. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 43, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Ruemmele, F.M.; Orlanski-Meyer, E.; Griffiths, A.M.; De Carpi, J.M.; Bronsky, J.; Veres, G.; Aloi, M.; Strisciuglio, C.; Braegger, C.P.; et al. Management of Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis, Part 1: Ambulatory Care-An Evidence-Based Guideline from European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, 257–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Ruemmele, F.M.; Orlanski-Meyer, E.; Griffiths, A.M.; De Carpi, J.M.; Bronsky, J.; Veres, G.; Aloi, M.; Strisciuglio, C.; Braegger, C.P.; et al. Management of Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis, Part 2: Acute Severe Colitis—An Evidence-Based Consensus Guideline from the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rheenen, P.F.; Aloi, M.; Assa, A.; Bronsky, J.; Escher, J.C.; Fagerberg, U.L.; Gasparetto, M.; Gerasimidis, K.; Griffiths, A.; Henderson, P.; et al. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: An ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivković, L.; Hojsak, I.; Trivić, I.; Sila, S.; Hrabač, P.; Konjik, V.; Senečić-Čala, I.; Palčevski, G.; Despot, R.; Žaja, O.; et al. IBD Phenotype at Diagnosis, and Early Disease-Course in Pediatric Patients in Croatia: Data from the Croatian National Registry. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 88, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, K.E.; Lakatos, P.L.; Arató, A.; Kovács, J.B.; Várkonyi, Á.; Szucs, D.; Szakos, E.; Sólyom, E.; Kovács, M.; Polgár, M.; et al. Incidence, Paris Classification, and Follow-up in a Nationwide Incident Cohort of Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberzadeh-Ardestani, B.; Anushiravani, A.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F.; Fakheri, H.; Vahedi, H.; Sheikhesmaeili, F.; Yazdanbod, A.; Moosavy, S.H.; Vosoghinia, H.; Maleki, I.; et al. Clinical Phenotype and Disease Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comparison Between Sporadic and Familial Cases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boaz, E.; Bar-Gil Shitrit, A.; Schechter, M.; Goldin, E.; Reissman, P.; Yellinek, S.; Koslowsky, B. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Families with Four or More Affected First-Degree Relatives. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, H.S.; Hong, S.P.; Cheon, J.H.; Kim, T.I.; Kim, W.H. Similar Clinical Characteristics of Familial and Sporadic Inflammatory Bowel Disease in South Korea. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 17120–17126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Pal, P.; Hutfless, S.; Ganesh, B.G.; Reddy, D.N. Familial Aggregation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in India: Prevalence, Risks and Impact on Disease Behavior. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.W.; Kwak, M.S.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, J.M.; Park, S.H.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, K.J.; Ye, B.D.; Byeon, J.S.; et al. Influence of a Positive Family History on the Clinical Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.P.; Martí, D.; Tosca, J.; Bosca-Watts, M.M.; Sanahuja, A.; Navarro, P.; Pascual, I.; Antón, R.; Mora, F.; Mínguez, M. Disease Severity and Treatment Requirements in Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaz, E.; Ariella, B.G.S.; Menachem, S.; Eran, G.; Petachia, R.; Shlomo, Y.; Koslowsky, B. P670 Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Associated with a More Adverse Disease Compared to Sporadic Cases. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, i578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, F.; Friedrich, M.; Wolf, C.; Stallhofer, J.; Angelberger, M.; Diegelmann, J.; Olszak, T.; Tillack, C.; Beigel, F.; Göke, B.; et al. The NOD2 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Rs72796353 (IVS4+10 A>C) Is a Predictor for Perianal Fistulas in Patients with Crohn’s Disease in the Absence of Other NOD2 Mutations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simovic, I.; Hilmi, I.; Ng, R.T.; Chew, K.S.; Wong, S.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Riordan, S.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N. ATG16L1 Rs2241880/T300A Increases Susceptibility to Perianal Crohn’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis on Inflammatory Bowel Disease Risk and Clinical Outcomes. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2024, 12, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, G.C.; Lee, M.J.; Hind, D.; Brown, S.R. Prognostic Factors Affecting Outcomes in Fistulating Perianal Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Tech. Coloproctol. 2017, 21, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sporadic (n = 352) | Familial (n = 88) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 151 (42.9) | 39 (44.3) | 0.810 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 14 (11–16) | 14 (12–16) | 0.829 |

| Very early onset disease (0–5 years) | 16 (4.5) | 4 (4.6) | 0.901 |

| Follow-up time (months) | 99.5 (55–148) | 109 (39–150) | 0.721 |

| Active smoking at diagnosis | 8 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 0.777 |

| Maximal disease extent | |||

| Proctitis | 44 (12) | 10 (11) | |

| Left-sided | 94 (27) | 21 (24) | 0.789 |

| Extensive | 214 (61) | 57 (65) | |

| Perianal disease ever (fissure, fistulae, abscess) | 10 (2.9) | 5 (5.7) | 0.196 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations ever | 51 (14.9) | 8 (9.2) | 0.227 |

| Sporadic (n = 524) | Familial (n = 131) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 337 (64.3) | 80 (61.1) | 0.490 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 14 (12–15) | 14 (12–16) | 0.397 |

| Very early onset disease (0–5 years) | 18 (3.4) | 6 (4.6) | 0.131 |

| Follow-up time (months) | 98 (54–147) | 102 (56–157) | 0.558 |

| Active smoking at diagnosis | 32 (6.1) | 9 (6.9) | 0.578 |

| Disease location ileal/colonic/ileo-colonic/isolated upper-GI | 223/54/242/5 (43/10/46/1) | 55/14/61/1 (42/11/46/1) | 0.995 |

| Disease behavior inflammatory/stricturing/penetrating | 418/54/52 (80/10/10) | 102/15/14 (78/11/11) | 0.887 |

| Upper GI involvement | 149 (31.7) | 38 (34.9) | 0.525 |

| Perianal disease ever | 158 (30.2) | 39 (29.8) | 0.932 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Muñoza, C.; Giordano, A.; Ricart, E.; Nos, P.; Iglesias, E.; Gisbert, J.P.; García-López, S.; Mesonero, F.; Pascual, I.; Tardillo, C.; et al. Influence of Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease History on the Use of Immunosuppressants, Biological Agents and Surgery in Patients with Pediatric-Onset of the Disease in the Era of Biological Therapies. Results from the ENEIDA Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103352

González-Muñoza C, Giordano A, Ricart E, Nos P, Iglesias E, Gisbert JP, García-López S, Mesonero F, Pascual I, Tardillo C, et al. Influence of Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease History on the Use of Immunosuppressants, Biological Agents and Surgery in Patients with Pediatric-Onset of the Disease in the Era of Biological Therapies. Results from the ENEIDA Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103352

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Muñoza, Carlos, Antonio Giordano, Elena Ricart, Pilar Nos, Eva Iglesias, Javier P. Gisbert, Santiago García-López, Francisco Mesonero, Isabel Pascual, Carlos Tardillo, and et al. 2025. "Influence of Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease History on the Use of Immunosuppressants, Biological Agents and Surgery in Patients with Pediatric-Onset of the Disease in the Era of Biological Therapies. Results from the ENEIDA Registry" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103352

APA StyleGonzález-Muñoza, C., Giordano, A., Ricart, E., Nos, P., Iglesias, E., Gisbert, J. P., García-López, S., Mesonero, F., Pascual, I., Tardillo, C., Rivero, M., Riestra, S., Mañosa, M., Zabana, Y., Gomollón, F., Calvet, X., García-Sepulcre, M. F., Gutiérrez, A., Pérez-Calle, J. L., ... Domènech, E., on behalf of the ENEIDA registry of GETECCU. (2025). Influence of Familial Inflammatory Bowel Disease History on the Use of Immunosuppressants, Biological Agents and Surgery in Patients with Pediatric-Onset of the Disease in the Era of Biological Therapies. Results from the ENEIDA Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103352