Effect of the Narcissism Subscale “Threatened Self” on the Occurrence of Burnout Among Male Physicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Participants

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

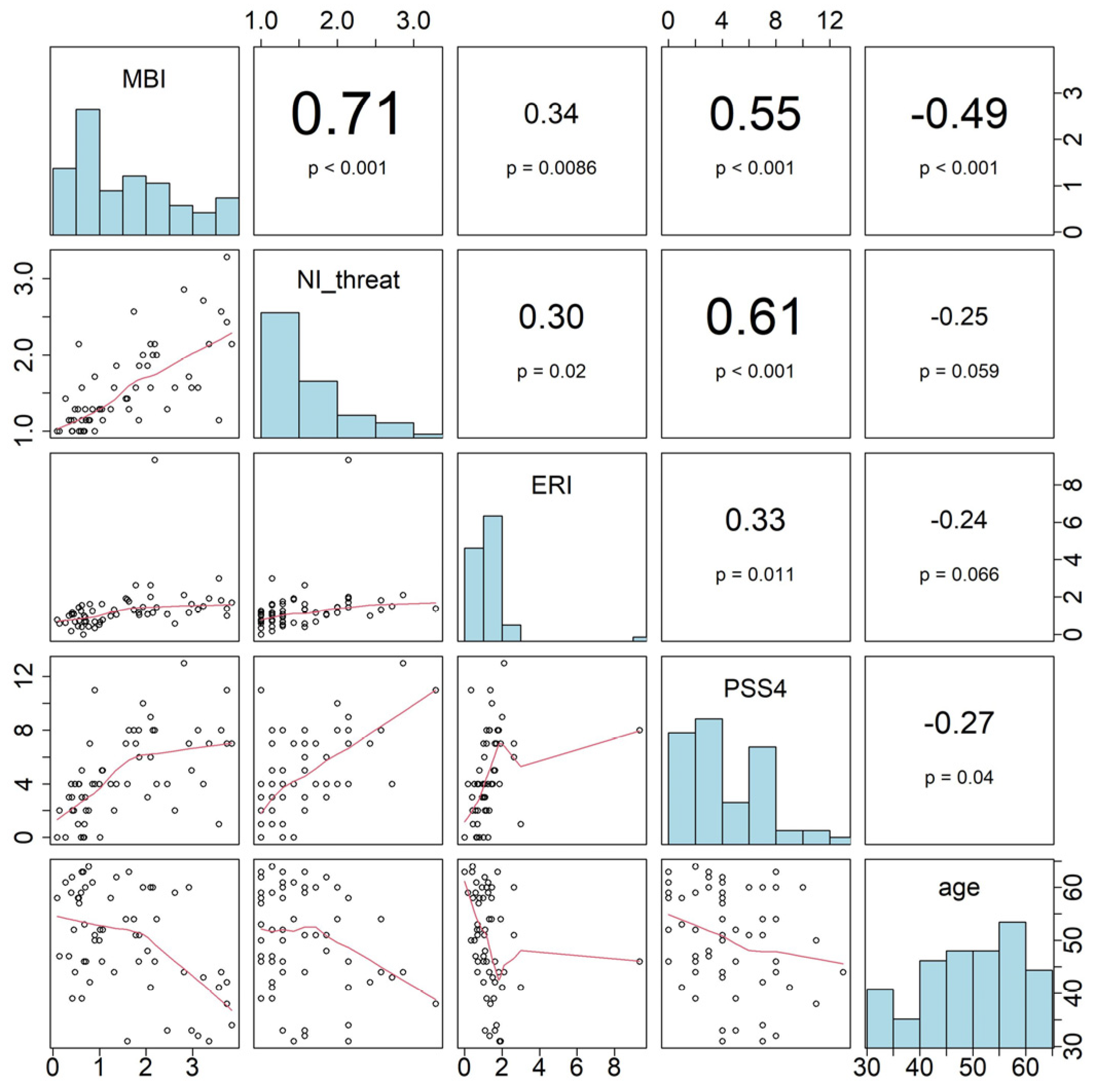

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CnS | Classic narcissistic self |

| DP | Depersonalization |

| EE | Emotional exhaustion |

| ERI | Effort–Reward Imbalance |

| HS | Hypochondriac self |

| IS | Idealistic self |

| MBI | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| NI-20 | Narcissism Inventory |

| PA | Personal accomplishment |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PSS4 | Perceived Stress Scale |

| TS | Threatened self |

References

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resourzces; Scarecrow Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arigoni, F.; Bovier, P.A.; Sappino, A.P. Trend of burnout among Swiss doctors. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010, 140, w13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Noseworthy, J.H. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govardhan, L.M.; Pinelli, V.; Schnatz, P.F. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn. Med. 2012, 76, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Lima, K.; Loureiro, S.R. Burnout, anxiety, depression, and social skills in medical residents. Psychol. Health Med. 2015, 20, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, K.S.; Huffman, L.B.; Phillips, G.S.; Carpenter, K.M.; Fowler, J.M. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 824.e1–824.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talih, F.; Warakian, R.; Ajaltouni, J.; Shehab, A.A.; Tamim, H. Correlates of Depression and Burnout Among Residents in a Lebanese Academic Medical Center: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acad. Psychiatry 2016, 40, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Narciso, V.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Dominici, G.; Talamo, A.; Girardi, P.; Lester, D.; Tatarelli, R. Burnout, hopelessness and suicide risk in medical doctors. Clin. Ter. 2010, 161, 511–514. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Bechamps, G.; Russell, T.; Dyrbye, L.; Satele, D.; Collicott, P.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.; Freischlag, J. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann. Surg. 2010, 251, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, F.; Liolios, E.; Persefonis, G.; Slater, J.; Kafetsios, K.; Niakas, D. Physician burnout and patient satisfaction with consultation in primary health care settings: Evidence of relationships from a one-with-many design. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2012, 19, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Rathert, C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: Exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, R.; Boss, R.W.; Chan, L.; Goldberg, J.; Mallon, W.K.; Moradzadeh, D.; Goodman, E.A.; McConkie, M.L. Burnout and its correlates in emergency physicians: Four years’ experience with a wellness booth. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1996, 3, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharp, D.M.; Walker, L.G.; Monson, J.R. Stress and burnout in colorectal and vascular surgical consultants working in the UK National Health Service. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gut, A.; Fröhli, D. Arbeitssituation der Assistenz- und Oberärztinnen und -ärzte Management Summary zur Mitgliederbefragung 2023 im Auftrag des Verbands Schweizerischer Assistenz- und Oberärztinnen und -ärzte (vsao); Verband Schweizerischer Assistenz- und Oberärztinnen und -ärzte (vsao): Bern, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, F.; Rozsnyai, Z.; Zumbrunn, B.; Laukenmann, J.; Kronenberg, R.; Streit, S. Assessing the mental wellbeing of next generation general practitioners: A cross-sectional survey. BJGP Open 2019, 3, bjgpopen19X101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon, G.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Känel, R.; Herr, R.M.; AEM, V.A.N.V.; Schmidt, B. Association of adaptive and maladaptive narcissism with personal burnout: Findings from a cross-sectional study. Ind. Health 2017, 55, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flett, G.L.; Nepon, T.; Hewitt, P.L.; Su, C.; Yacyshyn, C.; Moore, K.; Lahijanian, A. The Social Comparison Rumination Scale: Development, Psychometric Properties, and Associations With Perfectionism, Narcissism, Burnout, and Distress. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2024, 42, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincus, A.L.; Lukowitsky, M.R. Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A.L.; Ansell, E.B.; Pimentel, C.A.; Cain, N.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Levy, K.N. Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morf, C.C.; Rhodewalt, F. Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychol. Inq. 2001, 12, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, K.; Lammers, C.-H. Narzissmus—Persönlichkeitsvariable und persönlichkeitsstörung = Narcissism—Variable of personality and personality disorder. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2007, 57, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A. Factor analysis and construct validity of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. J. Personal. Assess. 1984, 48, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons, R.A. Narcissism: Theory and measurement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfer, T.; Spitzer, C.; Lammers, C.H. Narcissism-Normal, pathological, grandiose, vulnerable? Nervenarzt 2024, 95, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneke, F.-W.; Hilgenstock, B. Das Narzissmusinventar; Huber: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Daig, I.; Burkert, S.; Fischer, H.F.; Kienast, T.; Klapp, B.F.; Fliege, H. Development and factorial validation of a short version of the narcissism inventory (NI-20). Psychopathology 2010, 43, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M. The Psychology of Self-Affirmation: Sustaining the Integrity of the Self. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; Volume 21, pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kernis, M.H. Measuring self-esteem in context: The importance of stability of self-esteem in psychological functioning. J. Personal. 2005, 73, 1569–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoefler, A.; Athenstaedt, U.; Corcoran, K.; Ebner, F.; Ischebeck, A. Coping with Self-Threat and the Evaluation of Self-Related Traits: An fMRI Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.D.; Flores, J. Narcissus, exhausted: Self-compassion mediates the relationship between narcissism and school burnout. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 97, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzkopf, K.; Straus, D.; Porschke, H.; Znoj, H.; Conrad, N.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; von Känel, R. Empirical evidence for a relationship between narcissistic personality traits and job burnout. Burn. Res. 2016, 3, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Riedel, E.; Czens, F.; Petersohn, H.; Moellmann, H.L.; Schorn, L. When Do Narcissists Burn Out? The Bright and Dark Side of Narcissism in Surgeons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Raymond, M.; Kosty, M.; Satele, D.; Horn, L.; Pippen, J.; Chu, Q.; Chew, H.; Clark, W.B.; Hanley, A.E.; et al. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moellmann, H.L.; Rana, M.; Daseking, M.; Petersohn, H. Exploring grandiose narcissism among surgeons: A comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klerks, M.; Dumitrescu, R.; De Caluwé, E. The relationship between the Dark Triad and academic burnout mediated by perfectionistic self-presentation. Acta Psychol. 2024, 250, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Känel, R.; Princip, M.; Holzgang, S.A.; Garefa, C.; Rossi, A.; Benz, D.C.; Giannopoulos, A.A.; Kaufmann, P.A.; Buechel, R.R.; Zuccarella-Hackl, C.; et al. Coronary microvascular function in male physicians with burnout and job stress: An observational study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara, J.D.; Prasad, M.; Eleid, M.F.; Zhang, M.; Widmer, R.J.; Lerman, A. Association Between Work-Related Stress and Coronary Heart Disease: A Review of Prospective Studies Through the Job Strain, Effort-Reward Balance, and Organizational Justice Models. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.T.; Chu, A.; Austin, P.C.; Johnston, S.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Roifman, I.; Tusevljak, N.; Udell, J.A.; Frank, E. Comparison of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Outcomes Among Practicing Physicians vs the General Population in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1915983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Perrar, K.-M. Die Messung von Burnout Untersuchung einer deutschen Fassung des Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D) = Measuring burnout: A study of a German version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D). Diagnostica 1992, 38, 328–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gräfe, K.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W.; Löwe, B. Screening psychischer Störungen mit dem “Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D)”. Diagnostica 2004, 50, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, M.P. Burnout as a developmental process: Consideration of models. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Series in Applied Psychology: Social Issues and Questions; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, C.L.; Dougherty, T.W. A Review and an Integration of Research on Job Burnout. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, E.I.; Schlatzer, C.; Stehli, J.; Kaufmann, P.A.; Bloch, K.E.; Stradling, J.R.; Kohler, M. Effect of CPAP Withdrawal on myocardial perfusion in OSA: A randomized controlled trial. Respirology 2016, 21, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.; Dammann, G.; Küchenhoff, J.; Frommer, J.; Schoeneich, F.; Danzer, G.; Klapp, B.F. Psychosocial situation of living donors: Moods, complaints, and self-image before and after liver transplantation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2005, 11, Cr503–Cr509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Dreier, M.; Reinecke, L.; Müller, K.W.; Schmutzer, G.; Wölfling, K.; Beutel, M.E. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale—Psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Wege, N.; Pühlhofer, F.; Wahrendorf, M. A short generic measure of work stress in the era of globalization: Effort-reward imbalance. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödel, A.; Siegrist, J.; Hessel, A.; Brähler, E. Fragebogen zur Messung beruflicher Gratifikationskrisen. Z. Für Differ. Und Diagn. Psychol. 2004, 25, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O.; Brauchli, R.; Bauer, G.F. Effort-reward and work-life imbalance, general stress and burnout among employees of a large public hospital in Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 142, w13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buddeberg-Fischer, B.; Klaghofer, R.; Abel, T.; Buddeberg, C. Junior physicians’ workplace experiences in clinical fields in German-speaking Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2005, 135, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Holzgang, S.A.; Pazhenkottil, A.P.; Princip, M.; Auschra, B.; Euler, S.; von Känel, R. Burnout among Male Physicians: A Controlled Study on Pathological Personality Traits and Facets. Psych 2023, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzgang, S.A.; Princip, M.; Pazhenkottil, A.P.; Auschra, B.; von Känel, R. Underutilization of effective coping styles in male physicians with burnout. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, R.; Nasello, J.A.; Melchior, V.; Triffaux, J.M. Academic burnout among medical students: Respective importance of risk and protective factors. Public Health 2021, 198, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weilenmann, S.; Schnyder, U.; Keller, N.; Corda, C.; Spiller, T.R.; Brugger, F.; Parkinson, B.; von Känel, R.; Pfaltz, M.C. Self-worth and bonding emotions are related to well-being in health-care providers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig Llobet, M.; Sánchez Ortega, M.; Lluch-Canut, M.; Moreno-Arroyo, M.; Hidalgo Blanco, M.; Roldán-Merino, J. Positive Mental Health and Self-Care in Patients with Chronic Physical Health Problems: Implications for Evidence-based Practice. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2020, 17, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich-Rüfenacht, S.; Rousselot, A.; Künzler, A. Psychosoziale Aspekte chronischer Erkrankungen und deren Einfluss auf die Behandlung. Swiss Med. Forum Schweiz. Med. Forum 2013, 13. Available online: https://www.chronischkrank.ch/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/smf-01425pdf (accessed on 23 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Raju, A.; Nithiya, D.R.; Tipandjan, A. Relationship between burnout, effort-reward imbalance, and insomnia among Informational Technology professionals. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, L.E.; Bretones, F.D.; Rodríguez, J.A. The Effort-Reward Model and Its Effect on Burnout Among Nurses in Ecuador. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 760570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoman, Y.; Ranjbar, S.; Strippoli, M.P.; von Känel, R.; Preisig, M.; Guseva Canu, I. Relationship Between Effort-Reward Imbalance, Over-Commitment and Occupational Burnout in the General Population: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1606160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alle Schweizer Bundesbehörden. Tatsächliche Arbeitsstunden. Tatsächliches Arbeitsvolumen, Entwicklung der Arbeitszeit. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/arbeit-erwerb/erwerbstaetigkeit-arbeitszeit/arbeitszeit/tatsaechliche-arbeitsstunden.html (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Seidler, Z.E.; Dawes, A.J.; Rice, S.M.; Oliffe, J.L.; Dhillon, H.M. The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 49, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, P.J.; Lee, J.G.; Dworkin, S.L. “Real men don’t”: Constructions of masculinity and inadvertent harm in public health interventions. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, O. Gender and role models in the education of medical doctors: A qualitative exploration of gendered ways of thinking. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2020, 11, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, U.; Krugmann, C.S.; Plaumann, M. Preventing burnout? A systematic review of effectiveness of individual and combined approaches. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2012, 55, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weilenmann, S.; Ernst, J.; Petry, H.; Pfaltz, M.C.; Sazpinar, O.; Gehrke, S.; Paolercio, F.; von Känel, R.; Spiller, T.R. Health Care Workers’ Mental Health During the First Weeks of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Switzerland-A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 594340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, H.; Benzakour, L.; Moullec, G.; Buetti, N.; Nguyen, A.; Corbaz, S.; Roos, P.; Vieux, L.; Suard, J.C.; Weissbrodt, R.; et al. Mental health outcomes of ICU and non-ICU healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebo, P.; Favrod-Coune, T.; Mahler, L.; Moussa, A.; Cohidon, C.; Broers, B. A cross-sectional study of the health status of Swiss primary care physicians. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total Sample, n = 60 | Burnout, n = 30 | Control, n = 30 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median | IQR | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median | IQR | z-Value | p-Value | ||

| Age (years) | 49.85 (9.59) | 46.77 (10.56) | 45 | 18.25 | 52.93 (7.48) | 52 | 12 | −2.29 | 0.012 | ||||

| Body mass index (m2/kg) | 24.99 (2.96) | 25.63 (3.09) | 25.25 | 3.29 | 24.35 (2.72) | 23.92 | 2.90 | 1.75 | 0.094 | ||||

| Marital status | Married | 44 (73%) | 21 (70%) | 23 (77%) | 0.359 | ||||||||

| Other | 16 (27%) | 9 (30%) | 7 (23%) | ||||||||||

| Job status | full time | 48 (80%) | 25 (83%) | 23 (77%) | 0.527 | ||||||||

| part time | 12 (20%) | 5 (17%) | 7 (23%) | ||||||||||

| Working hours per week | 56.03 (10.40) | 57.35 (8.99) | 60.00 | 13.75 | 54.72 (11.66) | 55.00 | 14.375 | 0.332 | |||||

| Night work | 35 (58%) | 18 (60%) | 17 (57%) | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Employment | Self-employed | 20 (33%) | 10 (33%) | 10 (33%) | |||||||||

| hospital | 38 (63%) | 19 (63%) | 19 (63%) | ||||||||||

| Self-employed and hospital | 2 (3.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||||||||||

| Job satisfaction | Very dissatisfied | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| dissatisfied | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||||||

| Partly satisfied, partly dissatisfied | 14 (23%) | 14 (47%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||||||

| satisfied | 21 (35%) | 11 (37%) | 10 (33%) | ||||||||||

| Very satisfied | 23 (38%) | 3 (10%) | 20 (67%) | ||||||||||

| Medical specialty | Psychiatry | 6 (10%) | 2 (6.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.181 | ||||||||

| Cardiology | 3 (5%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||||||||||

| Internal medicine | 20 (33%) | 12 (40%) | 8 (27%) | ||||||||||

| Oncology | 4 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (13%) | ||||||||||

| Surgery | 11 (18.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | ||||||||||

| Neurology | 3 (5%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||||||||||

| Other | 13 (22%) | 9 (30%) | 4 (13.3%) | ||||||||||

| Variables | Total Sample, n = 60 | Burnout, n = 30 | Control, n = 30 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Median | IQR | Mean (SD) | Median | IQR | z-Value | p-Value | ||

| Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) | Total score | 1.68 (1.11) | 2.68 (0.57) | 2.62 | 0.91 | 0.68 (0.33) | 0.71 | 0.50 | 6.65 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Exhaustion | 19.53 (12.78) | 31.13 (5.84) | 30.50 | 8.75 | 7.93 (4.43) | 7.00 | 6.75 | 6.66 | <0.001 | |

| Depersonalization | 8.05 (7.26) | 13.77 (6.08) | 12.00 | 8.75 | 2.33 (1.67) | 2.00 | 2.00 | 6.45 | <0.001 | |

| Personal accomplishment | 8.68 (5.58) | 12.43 (4.61) | 12.00 | 6.75 | 4.93 (3.6) | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.45 | <0.001 | |

| Narcissism Inventory (NI20) | Threatened Self | 1.55 (0.54) | 1.87 (0.56) | 1.71 | 0.71 | 1.25 (0.30) | 1.14 | 0.29 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale Sum Score (PSS-4) | 4.66 (3.10) | 6.45 (2.73) | 7.00 | 4.00 | 2.93 (2.39) | 3.00 | 2.75 | <0.001 | ||

| Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERI) | Effort–Reward Ratio | 1.33 (1.22) | 1.84 (1.54) | 1.46 | 0.74 | 0.84 (0.41) | 0.76 | 0.50 | 3.477 | 0.002 |

| Effort Subscale | 6.36 (2.22) | 7.69 (1.37) | 8.00 | 2.00 | 5.01 (2.13) | 5.00 | 2.00 | <0.001 | ||

| Reward Subscale | 13.53 (3.80) | 11.97 (3.89) | 12.00 | 6.00 | 15.03 (3.09) | 15.00 | 4.00 | 0.001 | ||

| Overcommitment Subscale | 8.48 (3.78) | 10.68 (2.88) | 11.00 | 4.25 | 6.43 (3.37) | 7.00 | 4.00 | <0.001 | ||

| Coefficients: | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p | CI Lower | CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.32 | 0.64 | 2.08 | 0.04 * | 0.045 | 2.60 |

| Narcissism Subscale “Threatened self” | 1.10 | 0.21 | 5.14 | <0.001 *** | 0.669 | 1.52 |

| PSS-4 Sum score | 0.04 | 0.038 | 1.09 | 0.28 | −0.035 | 0.117 |

| Effort–Reward Ratio | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.68 | 0.50 | −0.106 | 0.216 |

| Age | −0.35 | 0.10 | −3.47 | 0.001 ** | −0.055 | −0.015 |

| Coefficients: | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p | CI Lower | CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.71 | 0.66 | 1.07 | 0.288 | −0.615 | 2.03 |

| Narcissism Subscale “Threatened self” | 1.06 | 0.20 | 5.16 | <0.001 *** | 0.646 | 1.47 |

| PSS-4 Sum score | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.68 | 0.498 | −0.049 | 0.099 |

| Effort–Reward Ratio | 0.42 | 0.17 | 2.49 | 0.016 * | 0.081 | 0.756 |

| Age | −0.028 | 0.01 | −2.84 | 0.006 ** | −0.049 | −0.008 |

| Coefficients: | Estimate | Odds Ratio | Std. Error | z-Value | p | CI Lower | CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 7.36 | - | 3.26 | 2.26 | 0.024 * | 0.819 | 13.900 |

| Narcissism Subscale “Threatened self” | −2.62 | 0.07 | 1.24 | −2.12 | 0.034 * | −5.110 | −0.140 |

| PSS-4 Sum score | −0.33 | 0.72 | 0.18 | −1.82 | 0.068 | −0.685 | 0.032 |

| Effort–Reward Ratio | −2.30 | 0.10 | 0.96 | −2.39 | 0.017 * | −4.220 | −0.374 |

| Age | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.733 | −0.080 | 0.113 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kreis, A.T.; von Känel, R.; Holzgang, S.A.; Pazhenkottil, A.; Keller, J.W.; Princip, M. Effect of the Narcissism Subscale “Threatened Self” on the Occurrence of Burnout Among Male Physicians. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103330

Kreis AT, von Känel R, Holzgang SA, Pazhenkottil A, Keller JW, Princip M. Effect of the Narcissism Subscale “Threatened Self” on the Occurrence of Burnout Among Male Physicians. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103330

Chicago/Turabian StyleKreis, Antonia Tiziana, Roland von Känel, Sarah Andrea Holzgang, Aju Pazhenkottil, Jeffrey Walter Keller, and Mary Princip. 2025. "Effect of the Narcissism Subscale “Threatened Self” on the Occurrence of Burnout Among Male Physicians" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103330

APA StyleKreis, A. T., von Känel, R., Holzgang, S. A., Pazhenkottil, A., Keller, J. W., & Princip, M. (2025). Effect of the Narcissism Subscale “Threatened Self” on the Occurrence of Burnout Among Male Physicians. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103330