Hemorrhage Versus Thrombosis: A Risk Assessment for Anticoagulation Management in Pelvic Ring and Acetabular Fractures—A Registry-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

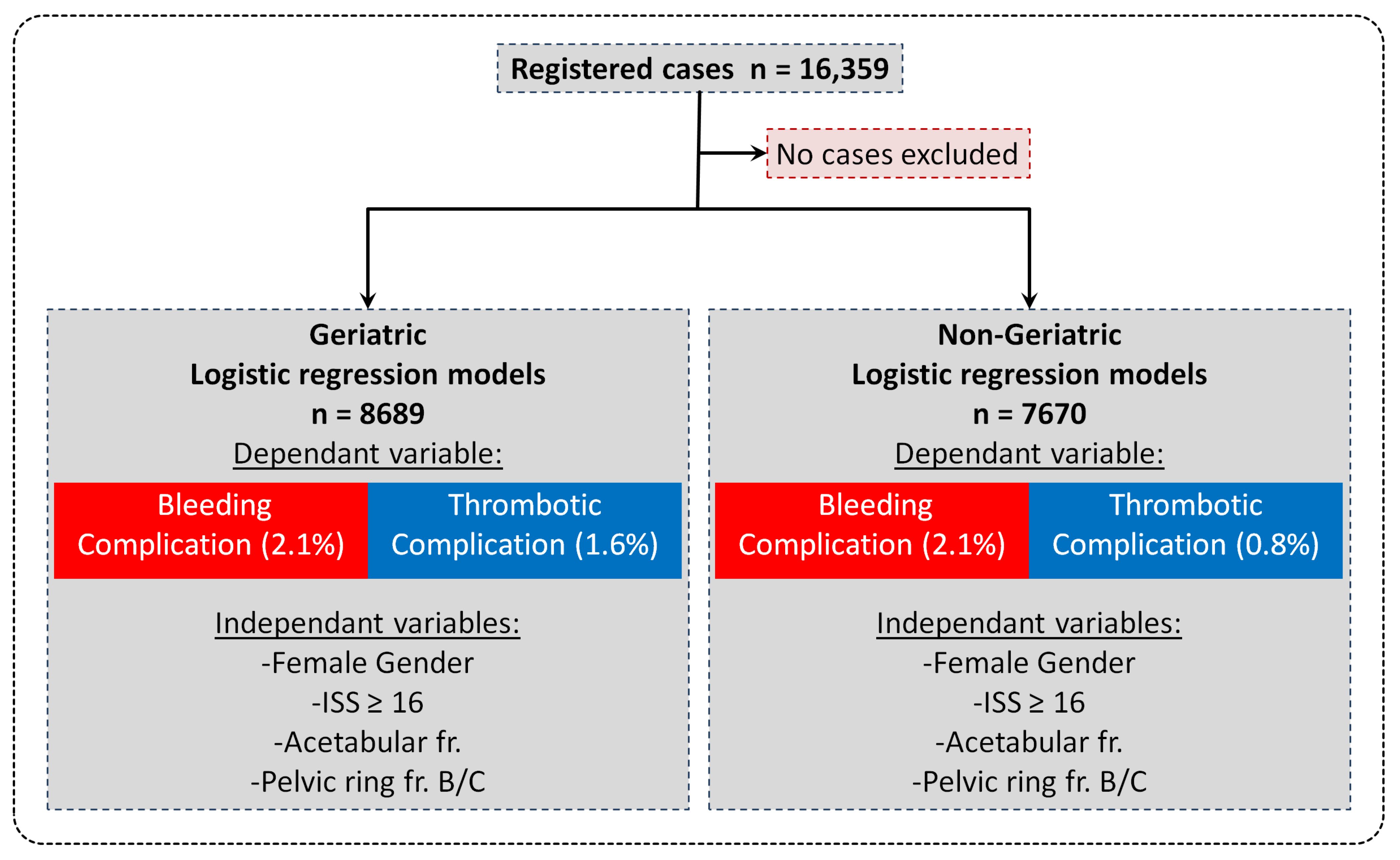

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patient Collective

2.2. Patients’ Characteristics and Data

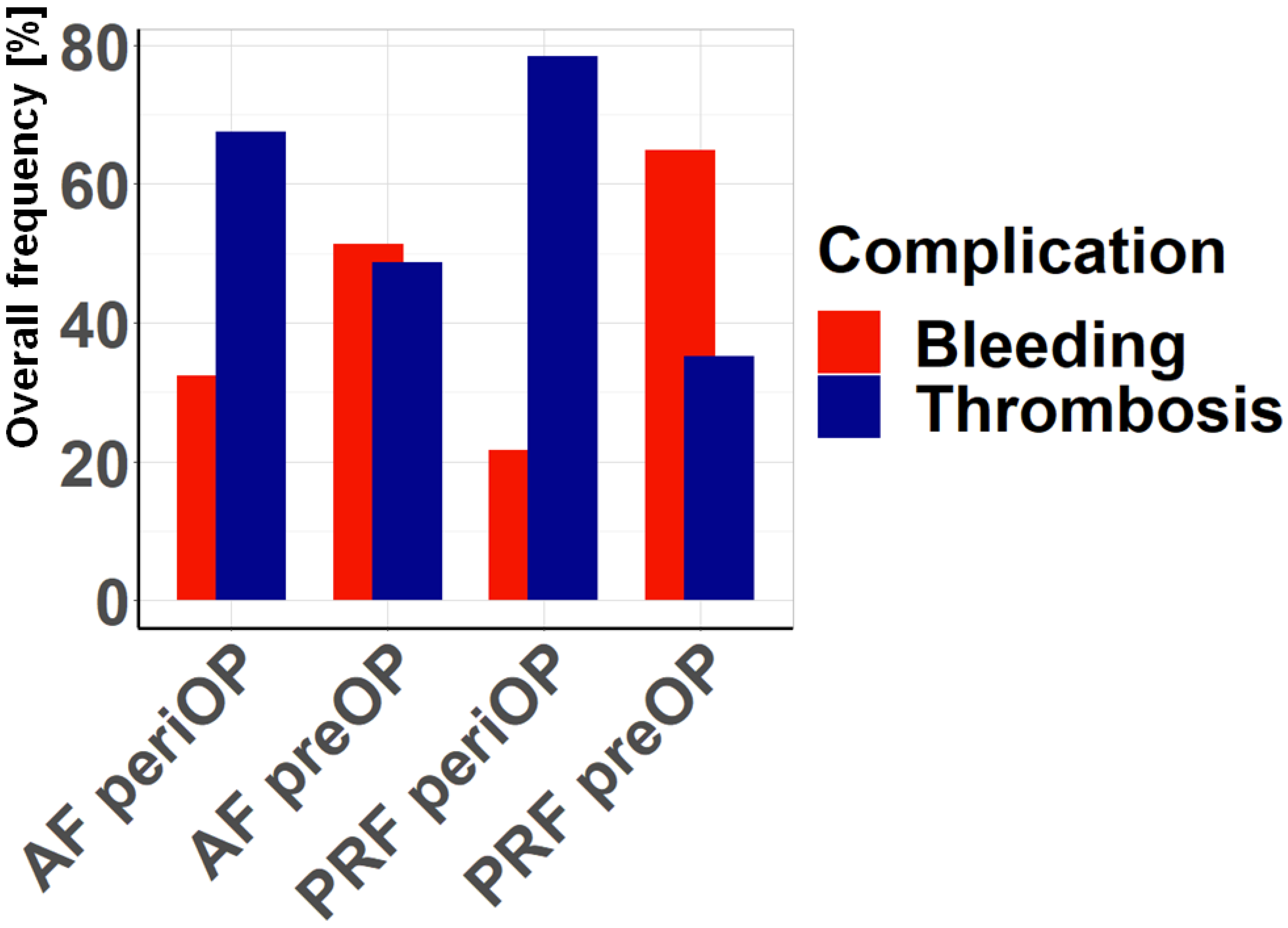

2.3. Survey

- “Which risk do you estimate to be higher preoperatively (admission until surgery) for acetabular fracture (AF)?” (A) Bleeding (B) Thrombosis

- “Which risk do you estimate to be higher perioperatively (surgery and inpatient up to 14 days after surgery) in the case of acetabular fracture (AF)?” (A) Bleeding (B) Thrombosis

- “Which risk do you estimate to be higher preoperatively (admission until surgery) for pelvic ring fractures (PRF)?” (A) Bleeding (B) Thrombosis

- “Which risk do you estimate to be higher perioperatively (surgery and inpatient up to 14 days after surgery) for pelvic ring fractures (PRF)?” (A) Bleeding (B) Thrombosis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Impact of Patient Characteristics on Complication Frequency

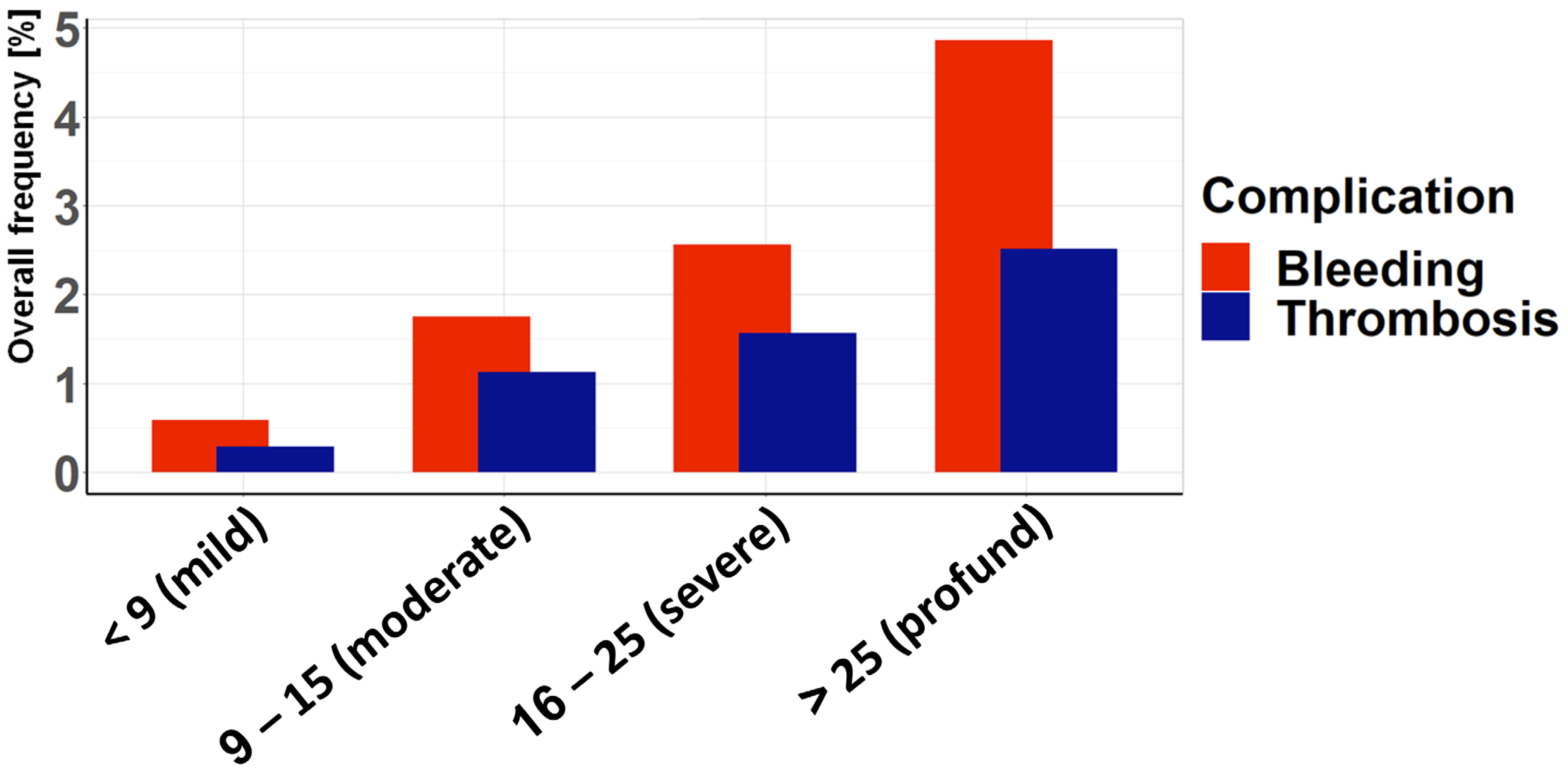

3.2. Association Between Age and ISS and the Complication Rate

3.3. Survey Results

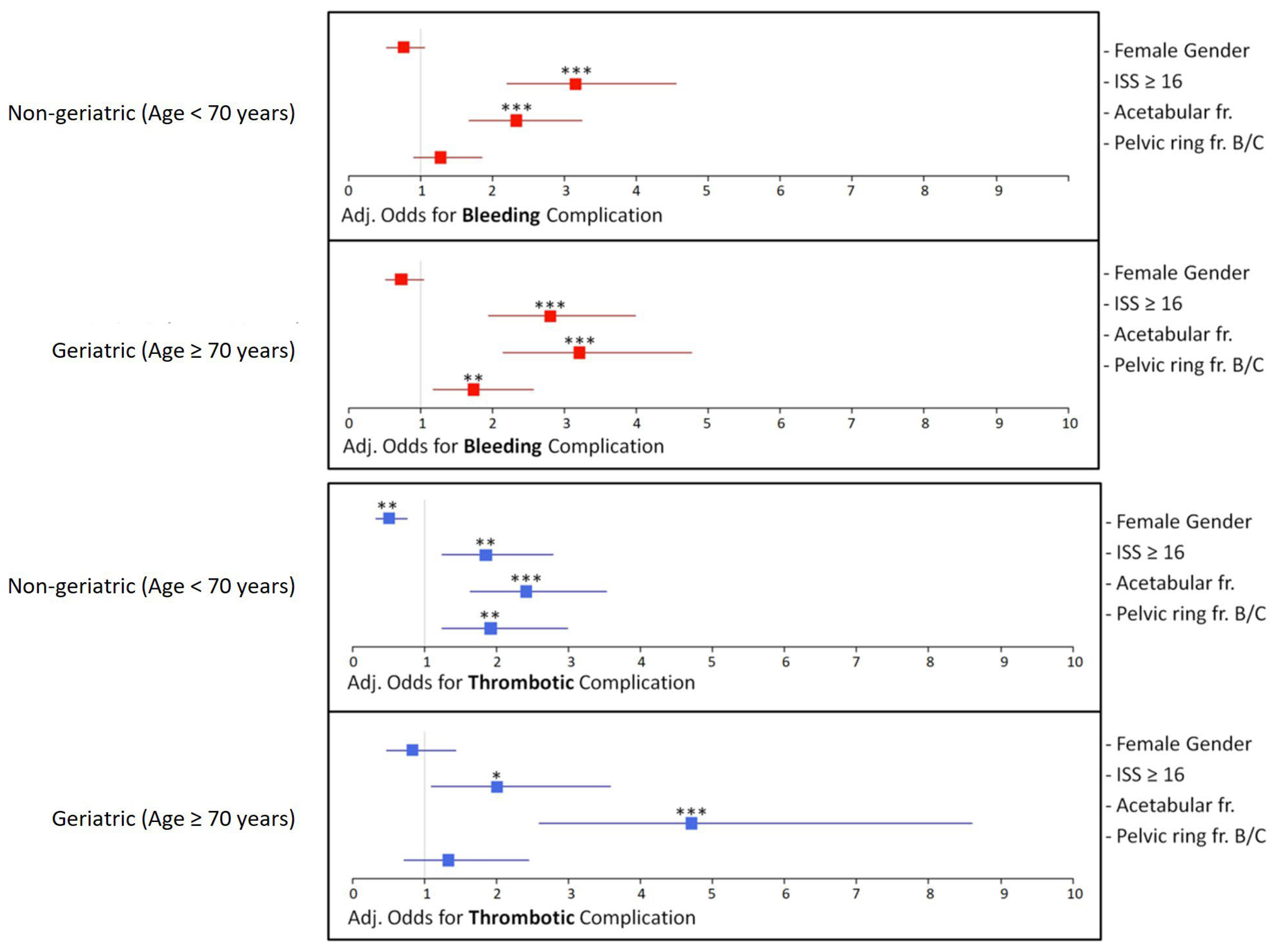

3.4. Logistic Regression Analysis—Odds Ratios and Adjusted Odds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rollmann, M.F.; Herath, S.C.; Kirchhoff, F.; Braun, B.J.; Holstein, J.H.; Pohlemann, T.; Menger, M.D.; Histing, T. Pelvic ring fractures in the elderly now and then—A pelvic registry study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 71, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, S.C.; Pott, H.; Rollmann, M.F.R.; Braun, B.J.; Holstein, J.H.; Hoch, A.; Stuby, F.M.; Pohlemann, T. Geriatric Acetabular Surgery: Letournel’s Contraindications Then and Now-Data From the German Pelvic Registry. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2019, 33 (Suppl. S2), S8–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibon, E.; Lu, L.; Goodman, S.B. Aging, inflammation, stem cells, and bone healing. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saul, D.; Khosla, S. Fracture Healing in the Setting of Endocrine Diseases, Aging, and Cellular Senescence. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 984–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; Rottbeck, U.; Hofbauer, V.; Raschke, M.; Stange, R. Pelvic ring fractures in the elderly. Underestimated osteoporotic fracture. Unfallchirurg 2011, 114, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuby, F.M.; Schaffler, A.; Haas, T.; Konig, B.; Stockle, U.; Freude, T. Insufficiency fractures of the pelvic ring. Unfallchirurg 2013, 116, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimerman, M.; Kristan, A.; Jug, M.; Tomazevic, M. Fractures of the acetabulum: From yesterday to tomorrow. Int. Orthop. 2021, 45, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, M.A.; Trulson, A.; Johannink, J.; Hirt, B.; Leis, A.; Hossfeld, M.; Histing, T.; Herath, S.C.; Amend, B. Robotic-assisted plate osteosynthesis of the anterior pelvic ring and acetabulum: An anatomical feasibility study. J. Robot. Surg. 2022, 16, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, M.M.; Herath, S.C.; Ellmerer, A.E.; Trulson, A.; Hossfeld, M.; Leis, A.; Ollig, A.; Histing, T.; Kuper, M.A.; Audretsch, C.K. Different coupling mechanisms for a novel modular plate in acetabular fractures-a comparison using a laparoscopic model. Front. Surg. 2024, 11, 1357581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, D.J.; Smith, W.R.; Suzuki, T. Management of hemorrhage in life-threatening pelvic fracture. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2009, 17, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.J.; Yoon, P.W.; Yoon, K.S. The effect of tranexamic acid in open reduction and internal fixation of pelvic and acetabular fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e29574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, P.R.; Moore, P.S.; Mansell, E.; Meredith, J.W.; Chang, M.C. External fixation or arteriogram in bleeding pelvic fracture: Initial therapy guided by markers of arterial hemorrhage. J. Trauma. 2003, 54, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Kandemir, U.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, K. Incidence and Risk Factors of Deep Vein Thrombosis in Patients With Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 25, 1076029619845066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major Extremity Trauma Research, C.; O’Toole, R.V.; Stein, D.M.; O’Hara, N.N.; Frey, K.P.; Taylor, T.J.; Scharfstein, D.O.; Carlini, A.R.; Sudini, K.; Degani, Y.; et al. Aspirin or Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin for Thromboprophylaxis after a Fracture. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.L.; Manson, R.J.; Turner, I.; Sindram, D.; Lawson, J.H. The balance of thrombosis and hemorrhage in surgery. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 2007, 21, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, W.H.; Code, K.I.; Jay, R.M.; Chen, E.; Szalai, J.P. A prospective study of venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, R.A.; Tressler, M.A.; Obremskey, W.T.; Kregor, P.J. Predicting blood loss in isolated pelvic and acetabular high-energy trauma. J. Orthop. Trauma 2007, 21, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Patel, S.; Vashisht, S.; Kumar, V.; Sehgal, I.S.; Chauhan, R.; Chaluvashetty, D.S.B.; Hemanth Kumar, D.K.; Jindal, D.K. Guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with pelvi-acetabular trauma. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 11, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.T.; Yu, A.T.; Lim, P.K.; Scolaro, J.A.; Shafiq, B. Chemoprophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in pelvic and/or acetabular fractures: A systematic review. Injury 2022, 53, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellera, C.A.; Rainfray, M.; Mathoulin-Pelissier, S.; Mertens, C.; Delva, F.; Fonck, M.; Soubeyran, P.L. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, A.; Lindelof, N.; Olofsson, B.; Berggren, M.; Gustafson, Y.; Nordstrom, P.; Stenvall, M. Effects of Geriatric Interdisciplinary Home Rehabilitation on Independence in Activities of Daily Living in Older People With Hip Fracture: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappenschneider, T.; Maderbacher, G.; Weber, M.; Greimel, F.; Holzapfel, D.; Parik, L.; Schwarz, T.; Leiss, F.; Knebl, M.; Reinhard, J.; et al. Special orthopaedic geriatrics (SOG)—A new multiprofessional care model for elderly patients in elective orthopaedic surgery: A study protocol for a prospective randomized controlled trial of a multimodal intervention in frail patients with hip and knee replacement. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossler, A.; Lukhaup, L.; Seidelmann, M.; Gaeth, C.; Dietz, S.O.; Audretsch, C.; Grutzner, P.; Windolf, J.; Neubert, A. Hemorrhage in Pelvic Ring Fractures After Low-Energy Trauma: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemenschneider, J.; Janko, M.; Vollrath, T.; Nau, C.; Marzi, I. Severe intraoperative vascular bleeding as main complication of acetabular fractures treated with plate osteosynthesis via the modified Stoppa approach. Injury 2023, 54, 110773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlemann, T.; Stengel, D.; Tosounidis, G.; Reilmann, H.; Stuby, F.; Stockle, U.; Seekamp, A.; Schmal, H.; Thannheimer, A.; Holmenschlager, F.; et al. Survival trends and predictors of mortality in severe pelvic trauma: Estimates from the German Pelvic Trauma Registry Initiative. Injury 2011, 42, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Noda, T.; Saito, T.; Uehara, T.; Shimamura, Y.; Ozaki, T. External iliac artery thrombosis following open reduction of acetabular fracture: A case report and literature review. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2020, 140, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probe, R.; Reeve, R.; Lindsey, R.W. Femoral artery thrombosis after open reduction of an acetabular fracture. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992, 283, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seadler, M.S.; Ferraresso, F.; Bansal, M.; Haugen, A.; Hayssen, W.G.; Flick, M.J.; de Moya, M.; Dyer, M.R.; Kastrup, C.J. Suppressing upregulation of fibrinogen after polytrauma mitigates thrombosis in mice. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2024, 97, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, H.C.; Moore, E.E.; McKinley, T.; Sauaia, A. Pathophysiology in patients with polytrauma. Injury 2022, 53, 2400–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Ismail, M.Y.; Citla Sridhar, D.; Nayak, L. Estrogen and thrombosis: A bench to bedside review. Thromb. Res. 2020, 192, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engbers, M.J.; van Hylckama Vlieg, A.; Rosendaal, F.R. Venous thrombosis in the elderly: Incidence, risk factors and risk groups. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkerson, W.R.; Sane, D.C. Aging and thrombosis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2002, 28, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) Baseline Characteristics | |||

| Total [%]; (n) | Geriatric (age ≥ 70a) [%]; (n) | Non-Geriatric (age < 70a) [%]; (n) | |

| Age Female Gender | 100% (16,359) 53.5% (8748/16,359) | 46.9% (7670/16,359) 74% (5677/7670) | 53.1% (8689/16,359) 35.3% (3071/8689) |

| (b) Injury Characteristics | |||

| Total [%]; (n) | Geriatric (age ≥ 70a) [%]; (n) | Non-Geriatric (age < 70a) [%]; (n) | |

| Seriously injured (ISS ≥ 16) | 32.8% (5364/16,359) | 15.9% (1221/7670) | 47.7% (4143/8689) |

| Acetabular fracture | 27.8% (4547/16,359) | 19.7% (1514/7670) | 34.9% (3033/8689) |

| Pelvic ring fracture B/C | 47.9% (7832/16,359) | 44.4% (3407/7670) | 50.9% (4425/8689) |

| (c) Outcome Characteristics | |||

| Total [%]; (n) | Geriatric (age ≥ 70a) [%]; (n) | Non-Geriatric (age < 70a) [%]; (n) | |

| Bleeding Complication | 2.1% (343/16,359) | 2.1% (160/7670) | 2.1% (183/8689) |

| Thrombotic Complication | 1.2% (200/16,359) | 0.8% (65/7670) | 1.6% (135/8689) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Audretsch, C.K.; Histing, T.; Schiltenwolf, A.; Seidler, S.; Höch, A.; Küper, M.A.; Herath, S.C.; Menger, M.M.; Working Group on Pelvic Fractures of the German Trauma Society. Hemorrhage Versus Thrombosis: A Risk Assessment for Anticoagulation Management in Pelvic Ring and Acetabular Fractures—A Registry-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103314

Audretsch CK, Histing T, Schiltenwolf A, Seidler S, Höch A, Küper MA, Herath SC, Menger MM, Working Group on Pelvic Fractures of the German Trauma Society. Hemorrhage Versus Thrombosis: A Risk Assessment for Anticoagulation Management in Pelvic Ring and Acetabular Fractures—A Registry-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103314

Chicago/Turabian StyleAudretsch, Christof K., Tina Histing, Anna Schiltenwolf, Sonja Seidler, Andreas Höch, Markus A. Küper, Steven C. Herath, Maximilian M. Menger, and Working Group on Pelvic Fractures of the German Trauma Society. 2025. "Hemorrhage Versus Thrombosis: A Risk Assessment for Anticoagulation Management in Pelvic Ring and Acetabular Fractures—A Registry-Based Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103314

APA StyleAudretsch, C. K., Histing, T., Schiltenwolf, A., Seidler, S., Höch, A., Küper, M. A., Herath, S. C., Menger, M. M., & Working Group on Pelvic Fractures of the German Trauma Society. (2025). Hemorrhage Versus Thrombosis: A Risk Assessment for Anticoagulation Management in Pelvic Ring and Acetabular Fractures—A Registry-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103314