Inpatient vs. Outpatient: A Systematic Review of Information Needs throughout the Heart Failure Patient Journey

Abstract

1. Introduction

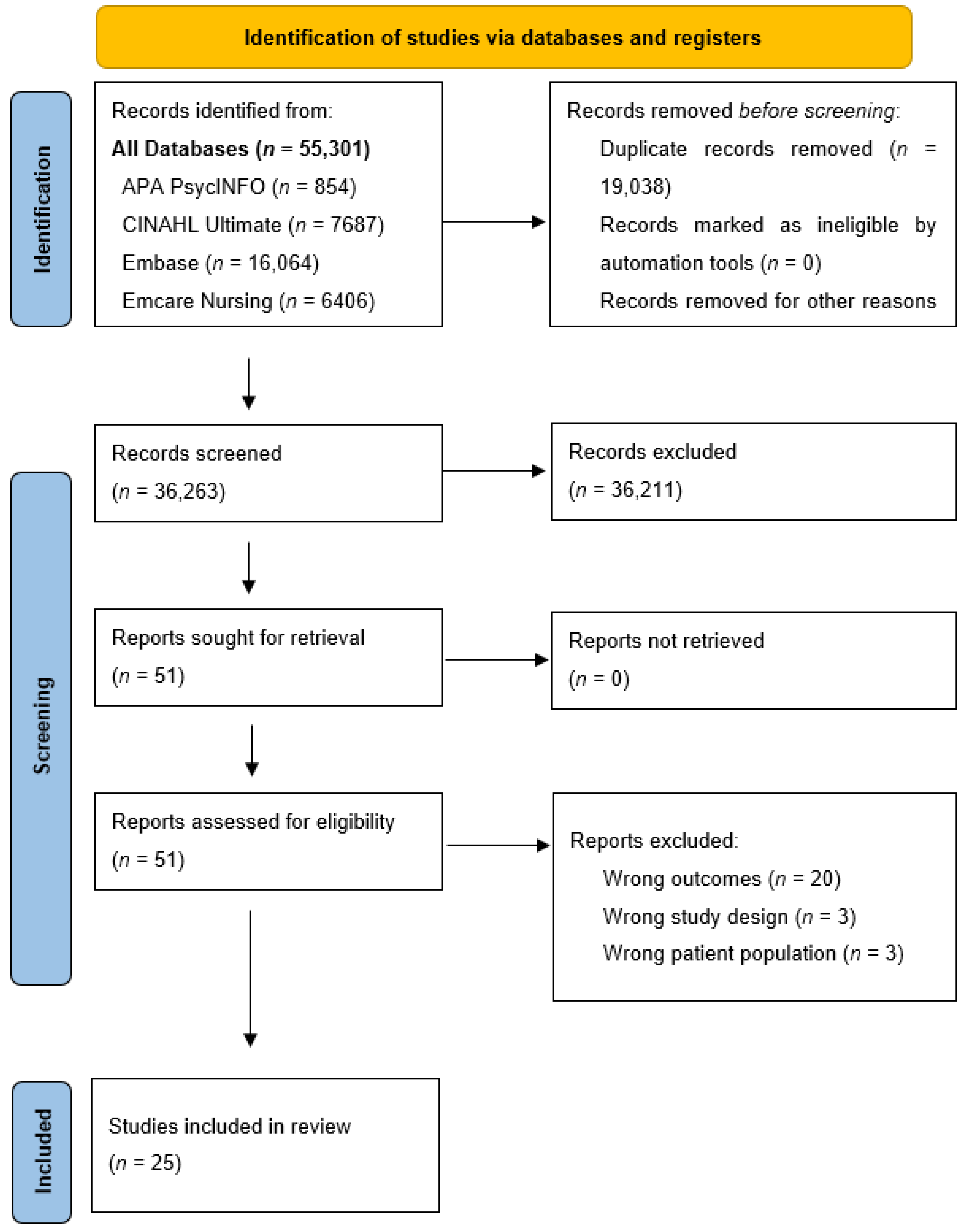

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process, Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Information Needs of Heart Failure Patients in Outpatient Settings

3.3. Information Needs of Heart Failure Patients in Inpatient Settings

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.; Coats, A.J.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roger, V.L. Epidemiology of Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.; Cole, G.; Asaria, P.; Jabbour, R.; Francis, D.P. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 171, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, A. The crucial role of patient education in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005, 7, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlister, F.A.; Stewart, S.; Ferrua, S.; McMurray, J.J. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: A systematic review of randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 810–819. [Google Scholar]

- Strömberg, A.; Mårtensson, J.; Fridlund, B.; Dahlström, U. Nurse-led heart failure clinics in Sweden. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2001, 3, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Loor, S.; Jaarsma, T. Nurse-managed heart failure programmes in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2002, 1, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, N.H.; Westland, H.; Groenwold, R.H.; Ågren, S.; Atienza, F.; Blue, L.; Bruggink-André de la Porte, P.W.; DeWalt, D.A.; Hebert, P.L.; Heisler, M.; et al. Do Self-Management Interventions Work in Patients with Heart Failure? An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2016, 133, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, S.A.; Wakefield, B.J.; Gunlock, T.L.; Wakefield, D.S. Heart failure self-management education: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2009, 7, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S. Hospital discharge education for patients with heart failure: What really works and what is the evidence? Crit. Care Nurse 2008, 28, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.M. A systematic review of transitional-care strategies to reduce rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung 2016, 45, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.M.; Rehman, M.; Johnson, W.D.; Magee, M.B.; Leonard, R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Healthcare Providers versus Patients’ Understanding of Health Beliefs and Values. Patient Exp. J. 2017, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Park, J.S.; Choi, E.Y.; Ahn, J.A. Comparison of learning needs priorities between healthcare providers and patients with heart failure. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.A.; Ashley, E.A.; Fedak, P.W.; Hawkins, N.; Januzzi, J.L.; McMurray, J.J.; Parikh, V.N.; Rao, V.; Svystonyuk, D.; Teerlink, J.R.; et al. Mind the Gap: Current Challenges and Future State of Heart Failure Care. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palis, A.G.; Quiros, P.A. Adult learning principles and presentation pearls. Middle East. Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 21, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Metra, M.; Mordi, I.; Gregson, J.; ter Maaten, J.M.; Tromp, J.; Anker, S.D.; Dickstein, K.; Hillege, H.L.; Ng, L.L.; et al. Heart failure in the outpatient versus inpatient setting: Findings from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018 User Guide. BMJ Open 2021, 11, 039246. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, L.; Nordgren, L. Heart Failure Patients’ Perceptions of Received and Wanted Information: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2019, 28, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, A.; Pardaens, S.; De Smedt, D.; Puddu, P.E.; Ciancarelli, M.C.; Dawodu, A.; De Sutter, J.; De Bacquer, D.; Clays, E. Sexual Activity in Heart Failure Patients: Information Needs and Association with Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Gill, L.; Muir, V.; Nadar, S.; Raja, Y.; Goyal, D.; Koganti, S. Do heart failure patients understand their diagnosis or want to know their prognosis? Heart failure from a patient’s perspective. Clin. Med. 2010, 10, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, R.; Selman, L.; Beynon, T.; Hodson, F.; Coady, E.; Read, C.; Walton, M.; Gibbs, L.; Higginson, I.J. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiansen, A.M.; Svanholm, J.R.; Schjødt, I.; Mølgaard Jensen, K.; Silén, C.; Karlgren, K. Patients with heart failure as co-designers of an educational website: Implications for medical education. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2017, 8, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lhermitte, C.; Viallet, A.; Rosset, E.; Godreuil, C. Assessing the educational needs of patients with heart failure. Soins 2019, 64, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianese, M.; De Astis, V.; Griffo, R. Assessing patients needs in outpatients with advanced heart failure. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2011, 76, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driel, A.G.; de Hosson, M.J.; Gamel, C. Sexuality of patients with chronic heart failure and their spouses and the need for information regarding sexuality. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2014, 13, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.D.; Reid, G.J.; Farvolden, P.; Deane, M.L.; Bisaillon, S. Learning needs of patients with congestive heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. 2003, 19, 413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.C.; Lan, V.M. Heart failure patient learning needs after hospital discharge. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2004, 17, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattini, E.; Lindsay, P.; Kerr, E.; Park, Y.J. Learning needs of congestive heart failure patients. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 1998, 13, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenhoff, B.D.; Feutz, C.; Conn, V.S.; Sagehorn, K.K.; Moranville-Hunziker, M. Patient education needs as reported by congestive heart failure patients and their nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, H.R.; Rupert, D.J.; Etta, V.; Peinado, S.; Wolff, J.L.; Lewis, M.A.; Chang, P.; Cené, C.W. Examining Information Needs of Heart Failure Patients and Family Companions Using a Previsit Question Prompt List and Audiotaped Data: Findings from a Pilot Study. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehby, D.; Brenner, P.S. Perceived learning needs of patients with heart failure. Heart Lung 1999, 28, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.D. Exploring Education Needs for Heart Failure Patients’ Transition of Care to Home. Doctoral Dissertation, ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ashour, A.; Al-Rawashdeh, S.; Alwidyan, M.; Al-Smadi, A.; Alshraifeen, A. Perceived Learning Needs of Patients with Heart Failure in Jordan: Perspectives of Patients, Caregivers, and Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 35, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Ahn, J.A.; Kang, S.M.; Kim, G.; Lee, S. Learning needs of patients with heart failure a descriptive, exploratory study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Chair, S.Y.; Chan, C.W.; Li, X.; Choi, K.C. Perceived learning needs of patients with heart failure in China: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Contemp. Nurse 2012, 41, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.M.; Chair, S.Y.; Chan, C.W.; Choi, K.C. Information needs of older people with heart failure: Listening to their own voice. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ong, S.F.; Foong, P.P.; Seah, J.S.; Elangovan, L.; Wang, W. Learning Needs of Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure in Singapore: A Descriptive Correlational Study. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 26, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyde, M.; Tuckett, A.; Peters, R.; Thompson, D.R.; Turner, C.; Stewart, S. Learning style and learning needs of heart failure patients (The Need2Know-HF patient study). Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2009, 8, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivynian, S.E.; Newton, P.J.; DiGiacomo, M. Patient preferences for heart failure education and perceptions of patient-provider communication. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 34, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buetow, S.A.; Coster, G.D. Do general practice patients with heart failure understand its nature and seriousness, and want improved information? Patient Educ. Couns. 2001, 45, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani, K.N.; Murray, S.A.; Grant, L. Multidimensional needs of patients living and dying with heart failure in Kenya: A serial interview study. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, P.S.; Peterson, L.M. Learning needs of cardiac patients. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 1984, 20, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.L.; Kushniruk, A.W.; Borycki, E.M. Patient journey mapping: Current practices, challenges and future opportunities in healthcare. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. 2020, 12, 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Jaarsma, T.; Hill, L.; Bayes-Genis, A.; La Rocca, H.B.; Castiello, T.; Čelutkienė, J.; Marques-Sule, E.; Plymen, C.M.; Piper, S.E.; Riegel, B.; et al. Self-care of heart failure patients: Practical management recommendations from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeder, K.M.; Ercole, P.M.; Peek, G.M.; Smith, C.E. Symptom perceptions and self-care behaviors in patients who self-manage heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Colvin, M.M.; Drazner, M.H.; Filippatos, G.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; Givertz, M.M.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017, 136, e137–e161. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.S.; Walker, S.; Smart, N.A.; Piepoli, M.F.; Warren, F.C.; Ciani, O.; Whellan, D.; O’Connor, C.; Keteyian, S.J.; Coats, A.; et al. Impact of Exercise Rehabilitation on Exercise Capacity and Quality-of-Life in Heart Failure: Individual Participant Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1430–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Mordi, I.R.; Bridges, C.; A Sagar, V.; Davies, E.J.; Coats, A.J.; Dalal, H.; Rees, K.; Singh, S.J.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, Cd003331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Sato, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Tsuchihashi-Makaya, M.; Kotooka, N.; Ikegame, T.; Takura, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Nagayama, M.; Goto, Y.; et al. Multidisciplinary Cardiac Rehabilitation and Long-Term Prognosis in Patients with Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e006798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Long, L.; Mordi, I.R.; Madsen, M.T.; Davies, E.J.; Dalal, H.; Rees, K.; Singh, S.J.; Gluud, C.; Zwisler, A.D. Exercise-Based Rehabilitation for Heart Failure: Cochrane Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, L.G.; Schopfer, D.W.; Zhang, N.; Shen, H.; Whooley, M.A. Participation in Cardiac Rehabilitation Among Patients with Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2017, 23, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshvani, N.; Subramanian, V.; Wrobel, C.A.; Solomon, N.; Alhanti, B.; Greene, S.J.; DeVore, A.D.; Yancy, C.W.; Allen, L.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Patterns of Referral and Postdischarge Utilization of Cardiac Rehabilitation Among Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure: An Analysis From the GWTG-HF Registry. Circ. Heart Fail. 2023, 16, e010144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, M.E.; Hsia, J.; Cannon, C.P.; Bonaca, M.P. Uptake of Newer Guideline-Directed Therapies in Heart Failure Patients with Diabetes or Chronic Kidney Disease. JACC Heart Fail. 2022, 10, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülow, C.; Clausen, S.S.; Lundh, A.; Christensen, M. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1, CD008986. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, M.R.; Mourilhe-Rocha, R.; Chang, H.-Y.; Volterrani, M.; Ban, H.N.; de Albuquerque, D.C.; Chung, E.; Fonseca, C.; Lopatin, Y.; Serrano, J.A.M.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on heart failure management: Global experience of the OPTIMIZE Heart Failure Care network. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 363, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, F.; Manla, Y.; Atallah, B.; Starling, R.C. Heart failure and COVID-19. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiler, S.E.; Ashton, J.J.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Unverferth, D.V.; Leier, C.V. An analysis of the determinants of exercise performance in congestive heart failure. Am. Heart J. 1987, 113, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadagno, D.; Nation, A.J.; Johnson, D.; Waitley, C.; Waitley, N.; Epstein, D.; Satterwhite, A. Cardiovascular disease and sexual functioning. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1995, 8, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaarsma, T.; Steinke, E.E. Sexual Counseling of the Cardiac Patient. In Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; Perk, J., Gohlke, H., Hellemans, I., Sellier, P., Mathes, P., Monpère, C., McGee, H., Saner, H., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2007; pp. 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, T.; Lesman-Leegte, I.; Couperus, M.F.; Sanderman, R.; Jaarsma, T. What keeps nurses from the sexual counseling of patients with heart failure? Heart Lung 2012, 41, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Doherty, S.; Murphy, A.W.; McGee, H.M.; Jaarsma, T. The CHARMS Study: Cardiac patients’ experiences of sexual problems following cardiac rehabilitation. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 12, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Doherty, S.; Byrne, M.; Murphy, A.W.; McGee, H.M. Cardiac Rehabilitation Staff Views about Discussing Sexual Issues with Coronary Heart Disease Patients: A National Survey in Ireland. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 10, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kolbe, N.; Kugler, C.; Schnepp, W.; Jaarsma, T. Sexual Counseling in Patients with Heart Failure: A Silent Phenomenon: Results From a Convergent Parallel Mixed Method Study. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMaughan, D.J.; Oloruntoba, O.; Smith, M.L. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. SAMHSA/CSAT Treatment Improvement Protocols. In Improving Cultural Competence; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, K.S.; Scott, L.D.; Britton, A.S. The use of supportive-educative and mutual goal-setting strategies to improve self-management for patients with heart failure. Home Healthc. Nurse 2007, 25, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toback, M.; Clark, N. Strategies to improve self-management in heart failure patients. Contemp. Nurse 2017, 53, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author Year Country Language | Setting In- vs. Out-Patient | Study Design Quality Appraisal (/5) * | Participant Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | NYHA Classifications | Females (n) or (%) | Age (n) or (Range) | |||

| Andersson, L. et al. [21] 2019 Sweden English | 6 primary healthcare centers Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 3/5 | 192 | Not reported | n = 97 51% | 48–96 (mean 80.3 ± 9.2) |

| Ashour, A. et al. [36] 2020 Jordan English | Outpatient department of 2 government hospitals Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 3/5 | 67 | I = 7.5% II = 11.9% III = 19.4% IV = 61.2% | n = 29 43% | 60 years or older (71.6%) |

| Baert, A. et al. [22] 2019 Italy and Belgium English | 4 hospitals Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 77 | I = 13.85% II = 72.3% III = 12.3% | n = 20 27% | 62.3 (SD = 10.6) |

| Banerjee, P. et al. [23] 2010 United Kingdom English | Patients identified via hospital database Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 3/5 | 90 | Not reported | n = 29 32% | 43–87 (median 71) |

| Boyde, M. et al. [41] 2009 Australia English | Large tertiary referral hospital In- and outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 55 | I = 9% II = 44% III = 44% IV = 3% | n = 17 31% | 33–83 years—mean 64.25 (SD = 13.21) |

| Buetow, S. et al. [43] 2001 New Zealand English | Large primary care organization Outpatients | Qualitative 4/5 | 62 | Not reported | n = 26 42% | 75 years (SD = 11) |

| Chan, A. et al. [29] 2003 Canada England | 1 hospital Inpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 34 | II = 17.6% III = 20.6% IV = 38.2% | n = 6 18% | 54.8 (14.88 SD), range 26 to 83 |

| Clark, J. et al. [30] 2004 USA English | Home care and outpatient HF clinic Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 33 | Not reported | n = 17 51% | 49–92 years, mean = 75.7 (SD = 10.56) |

| Frattini, E. et al. [31] 1998 Canada English | Hospital Inpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 50 | Not reported | n = 15 30% | 56–75 years |

| Hagenhoff, B. et al. [32] 2008 United Kingdom English | Hospital Inpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 30 | Not reported | n = 10 33% | 68 years (SD = 12.81) (range: 38–87) |

| Harding, R. et al. [24] 2008 United Kingdom English | Outpatient clinic and hospital wards In- and outpatients | Qualitative 5/5 | 20 | III = 70% III = 10% IV = 20% | n = 4 20% | 69 years (SD = 10.6) |

| Ivynian, S. et al. [42] 2020 Australian England | Inpatient lists from the cardiothoracic ward at a teaching hospital Inpatients | Qualitative 5/5 | 15 | II = 47% III = 53% | n = 5 33% | 55 years (median), IQR 52.69 |

| Jenkins, H. et al. [33] 2022 USA English | Outpatient at a cardiology clinic Outpatients | Qualitative 3/5 | 30 | Not reported | n = 11 37% | 60.3 (13.9) years (mean) for accompanied patients; 61.14 (17.2) for unaccompanied |

| Kim, S. et al. [37] 2013 Korea English | Cardiac outpatient clinic Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 5/5 | 121 | I = 49.1% II = 38.8% III = 12.1% | n = 41 34% | 19–88 years, 68% were >60 years of age, 19% were 50–59 and 13% were <50 |

| Kimani, K. et al. [44] 2018 Kenya English | Hospital In- and outpatients | Qualitative 5/5 | 18 | III = 56% IV = 44% | n = 10 56% | Not reported |

| Kristiansen, A. et al. [25] 2017 Denmark English | Hospital Outpatients | Qualitative 4/5 | 10 | Not reported | n = 2 20% | 47–78 years |

| Lhermitte, C. et al. [26] 2019 France French | Hospital Inpatients | Qualitative 4/5 | 15 | Not reported | n = 6 40% | 80.1 years |

| Min, D. et al. [14] 2020 Korea English | 2 large tertiary medical centers Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 5/5 | 100 | I = 24% II = 25% III = 35% IV = 16% | n = 58 58% | 72.15 years (range 44–94) |

| Ong, S. et al. [40] 2018 Singapore English | Acute tertiary hospital Inpatients | Quantitative descriptive 5/5 | 97 | I = 19.6% II = 30.9% III = 34% IV = 9.3% | n = 28 30% | 60.84 (SD = 11.34), range 32–89 |

| Pianese, M. et al. [27] 2011 Italy Italian | Hospital clinic Outpatients | Qualitative 5/5 | 50 | Not reported | n = 23 46% | 77.68 years |

| vanDriel, A. et al. [28] 2014 Belgium and Netherlands England | 3 hospitals Outpatients | Quantitative descriptive 4/5 | 52 | I = 15% II = 42% III = 23% IV = 15% | n = 11 21% | 65 years |

| Wehby, D. et al. [34] 1999 USA English | 2 Hospitals Inpatients | Quantitative descriptive 5/5 | 84 | II = 30% III = 56% IV = 14% | n = 45 54% | 71.8 (SD = 12.86), range 33–92 years |

| Williams, M. [35] 2019 USA English | Follow-up visit after hospital discharge Outpatients | Qualitative 5/5 | 12 | Not reported | n = 2 17% | 57.1 |

| Yu, M. et al. [38] 2012 China English | 3 Hospitals Inpatients | Quantitative descriptive 5/5 | 347 | I = 10% II = 55% III = 25% IV = 10% | n = 123 35% | 64 (SD = 13) |

| Yu, M. et al. [39] 2016 China English | Cardiovascular department of a university-affiliated hospital Outpatients | Qualitative 2/5 | 26 | II = 38.5% III = 34.6% IV = 26.9% | n = 11 42% | 58.62 (SD = 11.09) |

| Setting | Reference | Top 3 Information Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Outpatient | Andersson et al., 2019 [21] |

|

| Ashour et al., 2020 [36] |

| |

| Baert et al., 2019 [22] |

| |

| Banerjee et al., 2010 [23] |

| |

| Buetow et al., 2001 [43] |

| |

| Clark et al., 2004 [30] |

| |

| Jenkins et al., 2022 [33] |

| |

| Kristiansen et al., 2017 [25] |

| |

| Min et al., 2020 [14] |

| |

| Pianese et al., 2011 [27] |

| |

| vanDriel et al., 2014 [28] |

| |

| Williams et al., 2019 [35] |

| |

| Yu et al., 2016 [39] |

| |

| Inpatient | Chan et al., 2003 [29] |

|

| Frattini et al., 1998 [31] |

| |

| Hagenhoff et al., 1994 [32] |

| |

| Ivynian et al., 2020 [42] |

| |

| Kim et al., 2013 [37] |

| |

| Lhermitte et al., 2019 [26] |

| |

| Ong et al., 2018 [40] |

| |

| Wehby et al., 1999 [34] |

| |

| Yu et al., 2012 [38] |

| |

| Both outpatient and inpatient | Boyde et al., 2009 [41] |

|

| Harding et al., 2008 [24] |

| |

| Kimani et al., 2018 [44] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cotie, L.M.; Pakosh, M.; Ghisi, G.L.d.M. Inpatient vs. Outpatient: A Systematic Review of Information Needs throughout the Heart Failure Patient Journey. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041085

Cotie LM, Pakosh M, Ghisi GLdM. Inpatient vs. Outpatient: A Systematic Review of Information Needs throughout the Heart Failure Patient Journey. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(4):1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041085

Chicago/Turabian StyleCotie, Lisa M., Maureen Pakosh, and Gabriela Lima de Melo Ghisi. 2024. "Inpatient vs. Outpatient: A Systematic Review of Information Needs throughout the Heart Failure Patient Journey" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 4: 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041085

APA StyleCotie, L. M., Pakosh, M., & Ghisi, G. L. d. M. (2024). Inpatient vs. Outpatient: A Systematic Review of Information Needs throughout the Heart Failure Patient Journey. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(4), 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041085