Racial Disparities in Fertility Care: A Narrative Review of Challenges in the Utilization of Fertility Preservation and ART in Minority Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation

2.1. The Reproductive Lifespan

2.2. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Planned OC Utilization

2.3. Predicting Future Success after Planned OC in Minority Patients

2.4. Systemic Bias and Racism in Medicine

3. Fertility Preservation Prior to Gonadotoxic Therapies

3.1. Lack of Referrals and Counseling

3.2. Role of Insurance in Reducing Disparities

3.3. Streamlining Fertility Preservation Care

4. Limitations and Future Directions

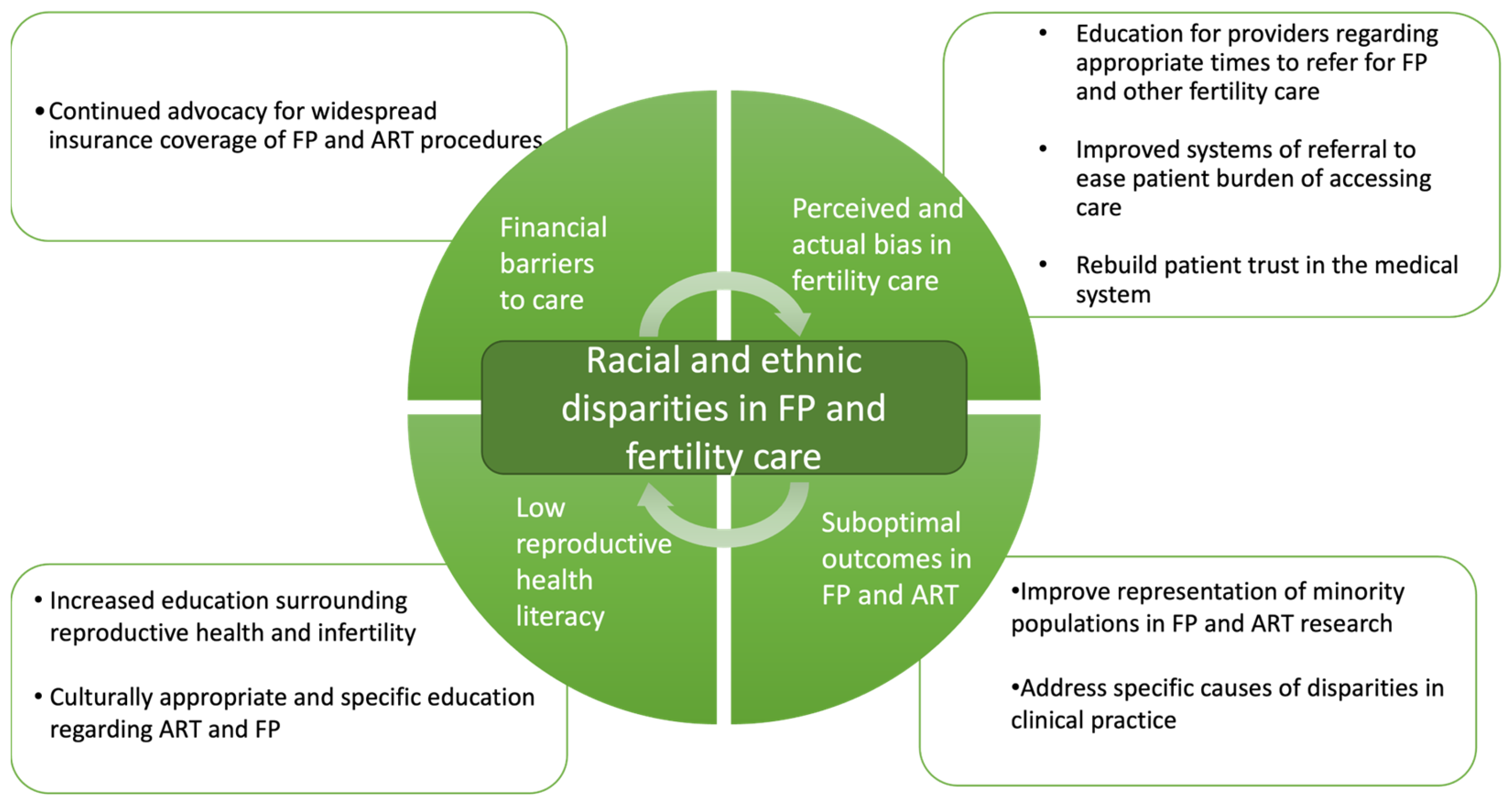

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oversight of Assisted Reproductive Technology. Available online: https://www.asrm.org/advocacy-and-policy/media-and-public-affairs/oversite-of-art/ (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- History of ASRM. Available online: https://www.asrm.org/about-us/about-asrm/history-of-asrm/ (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Merkison, J.M.; Chada, A.R.; Marsidi, A.M.; Spencer, J.B. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Systematic Review. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What Is Fertility Preservation? Available online: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/infertility/conditioninfo/fertilitypreservation (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Katler, Q.S.; Shandley, L.M.; Hipp, H.S.; Kawwass, J.F. National Egg-Freezing Trends: Cycle and Patient Characteristics with a Focus on Race/Ethnicity. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Bey, T.; Morris, J.; Jasper, E.; Edwards, D.R.V.; Thornton, K.; Richard-Davis, G.; Plowden, T.C. Systematic Review of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Where Do We Stand Today? FS Rev. 2021, 2, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daar, J.; Benward, J.; Collins, L.; Davis, J.; Davis, O.; Francis, L.; Gates, E.; Ginsburg, E.; Gitlin, S.; Klipstein, S.; et al. Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation for Women Seeking to Preserve Future Reproductive Potential: An Ethics Committee Opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.I.; Missmer, S.A.; Farland, L.V.; Ginsburg, E.S. Public Support in the United States for Elective Oocyte Cryopreservation. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mature Oocyte Cryopreservation: A Guideline. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 37–43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evidence-Based Outcomes after Oocyte Cryopreservation for Donor Oocyte in Vitro Fertilization and Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation: A Guideline. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 36–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, Z.; Lanes, A.; Ginsburg, E. Oocyte Cryopreservation Review: Outcomes of Medical Oocyte Cryopreservation and Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, J.K.; Grifo, J.A.; DeVore, S.M.; Hodes-Wertz, B.; Berkeley, A.S. Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation—10–15-Year Follow-up: Return Rates and Cycle Outcomes. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.Q.; Baker, K.; Vaughan, D.; Shah, J.S.; Korkidakis, A.; Ryley, D.A.; Sakkas, D.; Toth, T.L. Clinical Outcomes and Utilization from over a Decade of Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation. Reprod. BioMedicine Online 2021, 43, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, A.-L.; Schildauer, K.; Brännström, M. Elective Oocyte Freezing for Nonmedical Reasons: A 6-Year Report on Utilization and in Vitro Fertilization Results from a Swedish Center. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, B.-S.L.; Guarnaccia, M.M.; Ramirez, L.; Klein, J.U. Likelihood of Achieving a 50%, 60%, or 70% Estimated Live Birth Rate Threshold with 1 or 2 Cycles of Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürtin, Z.B.; Morgan, L.; O’Rourke, D.; Wang, J.; Ahuja, K. For Whom the Egg Thaws: Insights from an Analysis of 10 Years of Frozen Egg Thaw Data from Two UK Clinics, 2008–2017. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo, A.; García-Velasco, J.; Domingo, J.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J. Elective and Onco-Fertility Preservation: Factors Related to IVF Outcomes. Human. Reprod. 2018, 33, 2222–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, J.; Barbieri, R. Ovarian Life Cycle. In Yen & Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 167–205. [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston, A.; Ray, K.; Bacani, R.; Staggs, J.; Anderson, R.M.; Vassar, M. Inequities in Medically Assisted Reproduction: A Scoping Review. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 30, 2373–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galic, I.; Negris, O.; Warren, C.; Brown, D.; Bozen, A.; Jain, T. Disparities in Access to Fertility Care: Who’s in and Who’s out. FS Rep. 2020, 2, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komorowski, A.S.; Jain, T. A Review of Disparities in Access to Infertility Care and Treatment Outcomes among Hispanic Women. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhijani, R.; Godiwala, P.; Grady, J.; Christy, A.; Thornton, K.; Grow, D.; Engmann, L. Black Race Associated with Lower Live Birth Rate in Frozen-Thawed Blastocyst Transfer Cycles: An Analysis of 7,002 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Frozen-Thawed Blastocyst Transfer Cycles. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 117, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Definition of Fertility Preservation—NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms—NCI. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/fertility-preservation (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs)—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Tong, M.; Hill, L.; Artiga, S. Racial Disparities in Cancer Outcomes, Screening, and Treatment. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-cancer-outcomes-screening-and-treatment/ (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Fertility Preservation and Reproduction in Patients Facing Gonadotoxic Therapies: An Ethics Committee Opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 380–386. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, P.E.; Blakemore, J.K.; McCulloh, D.; Fino, M.E. Equal Opportunity for All? An Analysis of Race and Ethnicity in Fertility Preservation in New York City. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 3095–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Heytens, E.; Moy, F.; Ozkavukcu, S.; Oktay, K. Determinants of Access to Fertility Preservation in Women with Breast Cancer. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1932–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgboji, G.E.; Cordeiro Mitchell, C.N.; Bedrick, B.S.; Vaidya, D.; Tao, X.; Liu, Y.; Maher, J.Y.; Christianson, M.S. Predictive Factors for Fertility Preservation in Pediatric and Adolescent Girls with Planned Gonadotoxic Treatment. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 2713–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, P.; Persily, J.; Blakemore, J.K.; Licciardi, F.; Thakker, S.; Najari, B. Sociodemographic Differences in Utilization of Fertility Services among Reproductive Age Women Diagnosed with Cancer in the USA. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.R.; Balthazar, U.; Kim, J.; Mersereau, J.E. Trends of Socioeconomic Disparities in Referral Patterns for Fertility Preservation Consultation. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M.; Miller, M.; Cannella, C.; Daviskiba, S. Disparities in Fertility Preservation among Patients Diagnosed with Female Breast Cancer. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, G.P.; Block, R.G.; Clayman, M.L.; Kelvin, J.; Arvey, S.R.; Lee, J.-H.; Reinecke, J.; Sehovic, I.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Reed, D.; et al. If You Did Not Document It, It Did Not Happen: Rates of Documentation of Discussion of Infertility Risk in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Patients’ Medical Records. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, J.M.; Smith, J.F.; Ebbel, E.E.; Craig, A.; Katz, P.P.; Cedars, M.I.; Rosen, M.P. Racial, Socioeconomic, and Demographic Disparities in Access to Fertility Preservation in Young Women Diagnosed with Cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 4579–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.K.; McGuire, J.M.; Noncent, E.; Olivieri, J.F.; Smith, K.N.; Marsh, E.E. Disparities in Counseling Female Cancer Patients for Fertility Preservation. J Womens Health 2017, 26, 886–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besharati, M.; Woodruff, T.; Victorson, D. Young Adults’ Access to Fertility Preservation Services at National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program Minority/Underserved Community Sites: A Qualitative Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2016, 5, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Laws & Legislation. Available online: https://www.allianceforfertilitypreservation.org/state-legislation/ (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Gadson, A.K.; Anthony, K.E.; Raker, C.; Sauerbrun-Cutler, M.-T. Fertility preservation in an insurance mandated state: Outcomes from the rhode island fertility preservation registry. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, K.F.B.; Kraschel, K.; Seifer, D.B. State Insurance Mandates for in Vitro Fertilization Are Not Associated with Improving Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Utilization and Treatment Outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 313.e1–313.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkidakis, A.; DeSantis, C.E.; Kissin, D.M.; Hacker, M.R.; Koniares, K.; Yartel, A.; Adashi, E.Y.; Penzias, A.S. State Insurance Mandates and Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Assisted Reproductive Technology Utilization. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 121, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, L.; Artiga, S.; Damico, A. Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity, 2010–2022. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Family-Friendly Benefits Take Off. Available online: https://www.mercer.com/en-us/insights/us-health-news/family-friendly-benefits-take-off/ (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Cardozo, E.R.; Turocy, J.M.; James, K.E.; Freeman, M.P.; Toth, T.L. Employee Benefit or Occupational Hazard? How Employer Coverage of Egg Freezing Impacts Reproductive Decisions of Graduate Students. FS Rep. 2020, 1, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshua, A.S.; Abittan, B.; Bar-El, L.; Mullin, C.; Goldman, R.H. Employer-Based Insurance Coverage Increases Utilization of Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flink, D.M.; Sheeder, J.; Kondapalli, L.A. Do Patient Characteristics Decide If Young Adult Cancer Patients Undergo Fertility Preservation? J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2017, 6, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gadson, A.K.; Sauerbrun-Cutler, M.-T.; Eaton, J.L. Racial Disparities in Fertility Care: A Narrative Review of Challenges in the Utilization of Fertility Preservation and ART in Minority Populations. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041060

Gadson AK, Sauerbrun-Cutler M-T, Eaton JL. Racial Disparities in Fertility Care: A Narrative Review of Challenges in the Utilization of Fertility Preservation and ART in Minority Populations. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(4):1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041060

Chicago/Turabian StyleGadson, Alexis K., May-Tal Sauerbrun-Cutler, and Jennifer L. Eaton. 2024. "Racial Disparities in Fertility Care: A Narrative Review of Challenges in the Utilization of Fertility Preservation and ART in Minority Populations" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 4: 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041060

APA StyleGadson, A. K., Sauerbrun-Cutler, M.-T., & Eaton, J. L. (2024). Racial Disparities in Fertility Care: A Narrative Review of Challenges in the Utilization of Fertility Preservation and ART in Minority Populations. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(4), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041060