Australians’ Well-Being and Resilience During COVID-19: The Role of Trust, Misinformation, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Locus of Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- During the first year of the pandemic, how did Australians fare in terms of their well-being and resilience?

- (2)

- What were the psychological factors that promoted or hindered Australians’ well-being and resilience in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Survey

2.2.1. Outcome Variables

2.2.2. Predictor Variables

2.2.3. Control Variables

2.2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

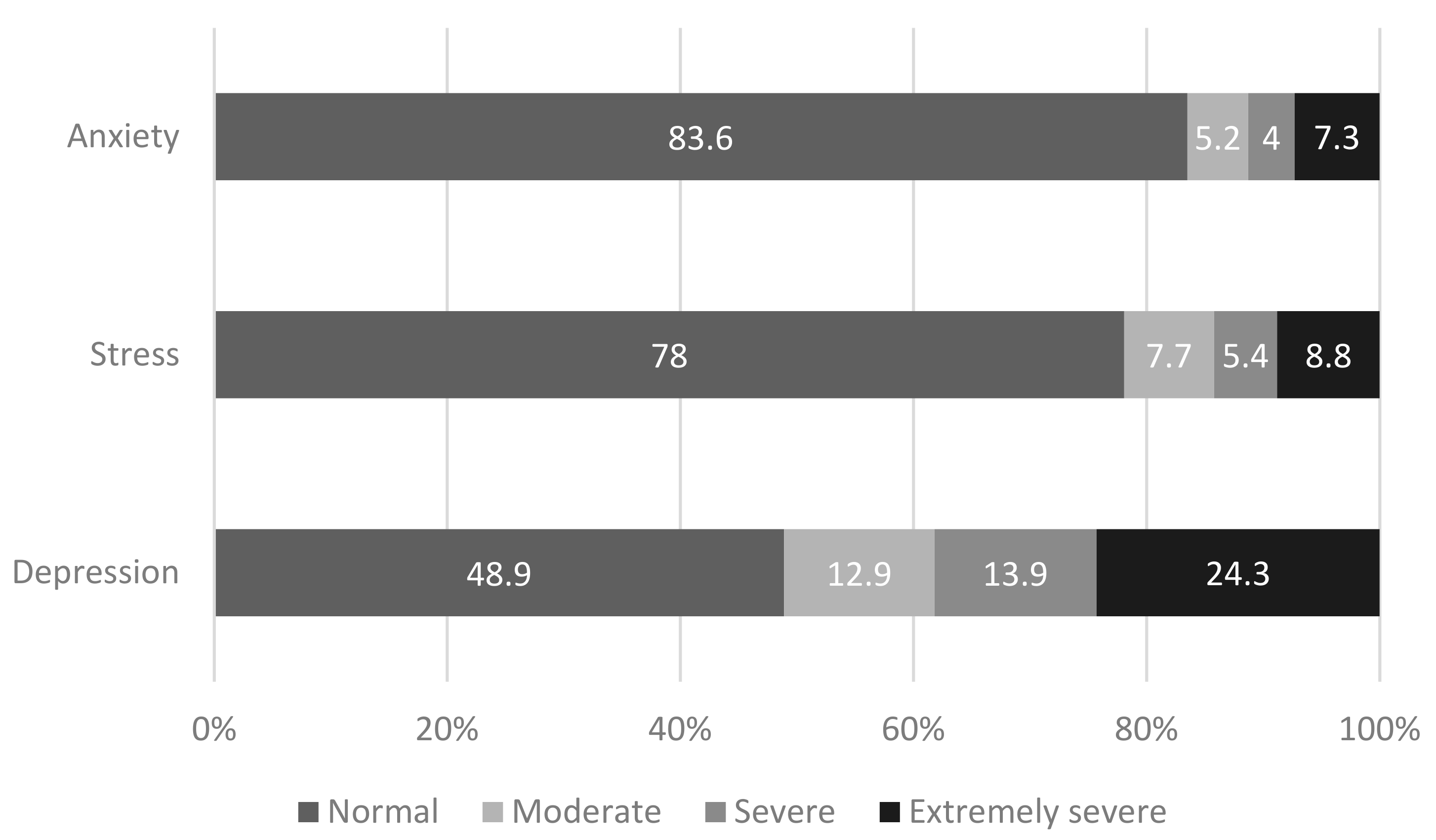

3.1. Well-Being and Resilience

3.2. Psychological Factors, Well-Being, and Resilience

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakefield, W.S.; Olusanya, O.A.; White, B.; Shaban-Nejad, A. Social determinants and indicators of COVID-19 among marginalized communities: A scientific review and call to action for pandemic response and recovery. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211019854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, J.; Roth, E.; Baird, M.; Carman, K.; Collins, R. A longitudinal study of predictors of serious psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, D.; Shah, A.; Doubeni, C.; Sia, I.; Wieland, M. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Preparedness of countries to face COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Strategic positioning and factors supporting effective strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. The health gap: The challenge of an unequal world. Lancet 2015, 386, 2442–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) at a Glance—29 November 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-29-november-2020 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Australia’s COVID Response Was One of the Best in the World at First. Why Do We Rank so Poorly Now? Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-07-28/australia-covid-response-from-good-to-bad/101277358 (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force, Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Trend Unemployment Rate Ends 2019 at 5.1%. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Business Indicators, Business Impacts of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Asmundson, G.; Taylor, S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 70, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtet, P.; Olié, E.; Debien, C.; Vaiva, G. Keep socially (but not physically) connected and carry on: Preventing suicide in the age of COVID-19. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 15527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reger, M.; Stanley, I.; Joiner, T. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—A perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1093–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchetti, M.; Lee, J.; Aschwanden, D.; Sesker, A.; Strickhouser, J.; Terracciano, A.; Sutin, A. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tull, M.; Edmonds, K.; Scamaldo, K.; Richmond, J.; Rose, J.; Gratz, K. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, M.; Abramowitz, J.; Berman, N.; Fabricant, L.; Olatunji, B. Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluck, L.; Gold, W.; Robinson, S.; Pogorski, S.; Galea, S.; Styra, R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health and Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Period in Australia. Available online: https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/mental-health-and-wellbeing-during-covid-19-period-australia (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Li, S.; Beames, J.; Newby, J.; Maston, K.; Christensen, H.; Werner-Seidler, A. The impact of COVID-19 on the lives and mental health of Australian adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Valgarðsson, V.; Smith, J.; Jennings, W.; Scotto di Vettimo, M.; Bunting, H.; McKay, L. Political trust in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 67 studies. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 31, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.; Uscinski, J.; Sutton, R.; Cichocka, A.; Nefes, T.; Ang, C.; Deravi, F. Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 2019, 40, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, B.; Niederdeppe, J.; Cappella, J.; Gaysynsky, A.; Kelley, D.; Oh, A.; Peterson, E.; Chou, W. Misinformation as a misunderstood challenge to public health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kużelewska, E.; Tomaszuk, M. Rise of conspiracy theories in the pandemic times. Int. J. Semiot. Law-Rev. Int. Sémiotique Jurid. 2022, 35, 2373–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, K.; Cvejic, E.; Nickel, B.; Copp, T.; Bonner, C.; Leask, J.; Ayre, J.; Batcup, C.; Cornell, S.; Dakin, T.; et al. COVID-19 misinformation trends in Australia: Prospective longitudinal national survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pummerer, L.; Böhm, R.; Lilleholt, L.; Winter, K.; Zettler, I.; Sassenberg, K. Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.P.; Efstratiou, A.; Komer, S.R.; Baxter, L.A.; Vasiljevic, M.; Leite, A.C. The impact of risk perceptions and belief in conspiracy theories on COVID-19 pandemic-related behaviours. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavolar, J.; Kacmar, P.; Hricova, M.; Schrötter, J.; Kovacova-Holevova, B.; Köverova, M.; Raczova, B. Intolerance of uncertainty and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Gen. Psychol. 2023, 150, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, D.; Mason, O. Perception of COVID-19 threat, low self-efficacy, and external locus of control lead to psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denson, N.; Dunn, K.; Ben, J.; Kamp, A.; Sharples, R.; Pitman, D.; Paradies, Y.; McGarty, C. Australians’ well-being and resilience during COVID-19. Available online: https://www.crisconsortium.org/research-reports/covid-resilience (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Kelly, A.; Halford, W. Responses to ethical challenges in conducting research with Australian adolescents. Aust. J. Psychol. 2007, 59, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, J.M.; Fisher, C.B. Assessing and enhancing the research consent capacity of children and youth. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2003, 7, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population: Census—Information on Sex and Age. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Income and Work: Census—Information on Income, Occupation and Employment. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Australia’s Population by Country of Birth—Statistics on Australia’s Estimated Resident Population by Country of Birth. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Education and Training: Census, 2021—Information on Qualifications, Educational Attendance and Type of Educational Institution. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Historical Population, 2021—Demographic Data Going Back as Far as Data is Available. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Kyriazos, T.; Stalikas, A.; Prassa, K.; Yotsidi, V. Can the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales Short be shorter? Factor structure and measurement invariance of DASS-21 and DASS-9 in a Greek, non-clinical sample. Psychology 2018, 9, 1095–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.; DiMatteo, M. A short-form measure of loneliness. J. Personal. Assess. 1987, 51, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Political issues and trust in government: 1964–1970. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.; Johnson, J.; Eber, H.; Hogan, R.; Ashton, M.; Cloninger, C.; Gough, H. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. J. Res. Personal. 2006, 40, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.; Norton, M.; Asmundson, G. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.; Franklin, J.; Andrews, G. A scale to measure locus of control of behaviour. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1984, 57, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaching for a Healthier Life: Facts on Socioeconomic Status and Health in the US. Available online: http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/news/Reaching%20for%20a%20Healthier%20life.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements Report. Available online: https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/natural-disasters/report (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Hardship, Distress, and Resilience: The Initial Impacts of COVID-19 in Australia. Available online: https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/hardship-distress-and-resilience-initial-impacts-covid-19-australia-1 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Fisher, J.; Tran, T.; Hammarberg, K.; Sastry, J.; Nguyen, H.; Rowe, H.; Popplestone, S.; Stocker, R.; Stubber, C.; Kirkman, M. Mental health of people in Australia in the first month of COVID-19 restrictions: A national survey. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossell, S.; Neill, E.; Phillipou, A.; Tan, E.; Toh, W.; Van Rheenen, T.; Meyer, D. An overview of current mental health in the general population of Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from the COLLATE project. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Leach, L.; Walsh, E.; Batterham, P.; Calear, A.; Phillips, C.; Olsen, A.; Doan, T.; LaBond, C.; Banwell, C. COVID-19 and mental health in Australia—A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloh, S.; Peleg, S.; Nudelman, G. Core self-evaluations as resilience and risk factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoychet, G.; Lenton-Brym, A.; Antony, M. The impact of COVID-19 anxiety on quality of life in Canadian adults: The moderating role of intolerance of uncertainty and health locus of control. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2022, 55, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, S.; Gelo, O.; Bassi, G.; Lo Coco, G.; Lagetto, G.; Esposito, G.; Pazzagli, C.; Salcuni, S.; Mazzeschi, C.; Giordano, C.; et al. The role of emotion regulation and intolerance to uncertainty on the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and distress. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19658–19669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurvinsdottir, R.; Thorisdottir, I.; Gylfason, H. The impact of COVID-19 on mental health: The role of locus on control and internet use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampe, H.; Danbolt, L.; Haver, A.; Stålsett, G.; Schnell, T. Locus of control moderates the association of COVID-19 stress and general mental distress: Results of a Norwegian and a German-speaking cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Long, Q.; Huang, G.; Huang, L.; Luo, S. Different roles of interpersonal trust and institutional trust in COVID-19 pandemic control. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 293, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Jung, J.; Kim, H. Political trust, mental health, and the coronavirus pandemic: A cross-national study. Res. Aging 2023, 45, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J. Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos Int. Rev. Soc. Sci. 2006, 59, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, A.; Dunn, K.; Sharples, R.; Denson, N.; Diallo, T. Understanding Trust in Contemporary Australia Using Latent Class Analysis. Cosmop. Civ. Soc. Interdiscip. J. 2023, 15, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. What makes democracy work? Natl. Civ. Rev. 1993, 82, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moesen, W.; Van Puyenbroeck, T.; Cherchye, L. Trust as Societal Capital: Economic Growth in European Regions; CES-Discussion Paper Series (DPS) 00.01; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zak, P.; Knack, S. Trust and growth. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, G.; Giambona, F.; Vassallo, E.; Vassiliadis, E. A measure of trust: The Italian regional divide in a latent class approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 209–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/trust/2020-trust-barometer (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/trust/2021-trust-barometer (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer. Available online: https://www.edelman.com.au/sites/g/files/aatuss381/files/2022-02/Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%202022%20-%20Australia%20Country%20Report.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Douglas, K. COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2021, 24, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.; Sutton, R.; Cichocka, A. The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 26, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.; O’brien, W.; Stuart, B.; Stoner, L.; Batten, J.; Wadsworth, D.; Askew, C.; Badenhorst, C.; Byrd, E.; Draper, N.; et al. Physical activity, mental health and wellbeing of adults within and during the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, in the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, R.; Kaufman, D.; Settle, K.; Duckworth, M. Policy leadership challenges in supporting community resilience. In Strategies for Supporting Community Resilience: Multinational Experiences: CRISMART 2015; The Swedish Defence University: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, N.; Delfabbro, P.; Balzan, R. COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs and their relationship with perceived stress and pre-existing conspiracy beliefs. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 166, 110201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Saunders, K.; Farhart, C. Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: The moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. Am. J. Political Sci. 2016, 60, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, J.; Douglas, K. Belief in conspiracy theories: Basic principles of an emerging research domain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agley, J.; Xiao, Y. Misinformation about COVID-19: Evidence for differential latent profiles and a strong association with trust in science. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peucker, M.; Fisher, T. Mainstream media use for far-right mobilisation on the alt-tech online platform Gab. Media Cult. Soc. 2023, 45, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N. Untrustworthy news and the media as “enemy of the people”? How a populist worldview shapes recipients’ attitudes toward the media. Int. J. Press Politics 2019, 24, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A.; Holt, K. Paradoxical populism: How PEGIDA relates to mainstream and alternative media. Inform. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1665–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecula, D.; Pickup, M. How populism and conservative media fuel conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19 and what it means for COVID-19 behaviors. Res. Politics 2021, 8, 2053168021993979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peucker, M.; Spaaij, R. Alternative epistemology in far-right anti-publics: A qualitative study of Australian activists. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, P.; Looi, J. Moral injury and psychiatrists in public community mental health services. Australas. Psychiatry 2022, 30, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddlestone, M.; Green, R.; Douglas, K. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. Words Matter: How New Zealand’s Clear Messaging Helped Beat Covid. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/26/words-matter-how-new-zealands-clear-messaging-helped-beat-covid (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Covid Australia: Sydney Celebrates End of 107-Day Lockdown. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-58866464 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Melbourne Marks 200 Days of COVID-19 Lockdowns Since the Pandemic Began—ABC News. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-19/melbourne-200-days-of-covid-lockdowns-victoria/100386078 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- WA Has a ‘Go Hard, Go Early’ Approach to COVID-19 Lockdowns, But What Is the Pathway Out? Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-18/wa-hard-lockdown-approach-pathway-out-of-covid/100301206 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Liu, C.; Zhang, E.; Wong, G.; Hyun, S. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for US young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpox Is on the Rise in Australia, Prompting Calls to Limit Intimate Partners and Keep Contact Tracing Details—ABC News. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-07-26/mpox-cases-outbreak-australia-victoria-spike-infections/104119360 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

| Variable | Range | Mean | SD | # of Items | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0–9 | 1.51 | 2.07 | 3 | 0.853 |

| Stress | 0–9 | 2.15 | 2.11 | 3 | 0.837 |

| Depression | 0–9 | 2.18 | 2.30 | 3 | 0.867 |

| Loneliness | 8–32 | 22.77 | 5.79 | 8 | 0.870 |

| Resilience | 1–5 | 3.31 | .83 | 6 | 0.889 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trust in federal government | r | 1 | 0.477 | –0.447 | 0.186 | −0.062 | 0.056 | −0.052 | −0.129 | −0.105 | −0.171 | 0.145 | 5.148 | 1.304 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.037 | 0.052 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2. Trust in state government | r | 1 | −0.243 | 0.171 | −0.261 | 0.027 | −0.041 | −0.128 | −0.072 | −0.106 | 0.078 | 5.292 | 1.359 | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.310 | 0.128 | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.004 | |||||

| 3. Distrust of government in general | r | 1 | −0.333 | 0.221 | 0.171 | 0.195 | 0.195 | 0.211 | 0.207 | −0.205 | 4.386 | 1.083 | ||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 4. Interpersonal trust | r | 1 | −0.244 | –0.310 | −0.411 | −0.440 | −0.420 | −0.433 | 0.430 | 3.443 | 0.743 | |||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 5. COVID-19 beliefs | r | 1 | 0.191 | 0.297 | 0.320 | 0.343 | 0.153 | −0.139 | 2.827 | 1.231 | ||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 6. IOU: Prospective anxiety | r | 1 | 0.715 | 0.369 | 0.466 | 0.306 | −0.345 | 2.922 | 0.787 | |||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 7. IOU: Inhibitory anxiety | r | 1 | 0.632 | 0.652 | 0.493 | −0.557 | 2.407 | 0.980 | ||||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| 8. External locus of control | r | 1 | 0.627 | 0.519 | −0.598 | 2.944 | 0.660 | |||||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| 9. Depression, anxiety, and stress a | r | 1 | 0.569 | −0.553 | 5.806 | 5.912 | ||||||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 10. Loneliness a | r | 1 | −0.545 | 2.156 | 0.724 | |||||||||

| p | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| 11. Resilience b | r | 1 | 3.314 | 0.826 | ||||||||||

| p | ||||||||||||||

| Depression, Anxiety, and Stress a | Loneliness a | Resilience b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | Beta | p | B (SE) | Beta | p | B (SE) | Beta | p | |

| Trust in federal government | −0.085 (0.119) | −0.020 | 0.475 | −0.032 (0.017) | −0.058 | 0.061 | 0.014 (0.018) | 0.021 | 0.457 |

| Trust in state government | 0.190 (0.108) | 0.045 | 0.079 | −0.003 (0.016) | −0.006 | 0.842 | 0.013 (0.017) | 0.021 | 0.447 |

| Distrust of government in general | 0.112 (0.138) | 0.021 | 0.419 | 0.006 (0.020) | 0.010 | 0.743 | −0.057 (0.021) | −0.074 | 0.008 |

| Interpersonal trust | −1.017 (0.206) | −0.135 | <0.001 | −0.199 (0.030) | −0.209 | <0.001 | 0.155 (0.032) | 0.140 | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 beliefs | 0.514 (0.117) | 0.109 | <0.001 | −0.021 (0.017) | −0.036 | 0.207 | 0.069 (0.018) | 0.100 | <0.001 |

| IOU: Prospective anxiety | 0.242 (0.239) | 0.033 | 0.313 | −0.033 (0.034) | −0.035 | 0.339 | 0.048 (0.037) | 0.045 | 0.192 |

| IOU: Inhibitory anxiety | 1.827 (0.227) | 0.311 | <0.001 | 0.191 (0.033) | 0.256 | <0.001 | −0.278 (0.035) | −0.323 | <0.001 |

| External locus of control | 1.984 (0.269) | 0.228 | <0.001 | 0.234 (0.039) | 0.212 | <0.001 | −0.397 (0.042) | −0.310 | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.563 | 0.429 | 0.505 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Denson, N.; Dunn, K.M.; Kamp, A.; Ben, J.; Pitman, D.; Sharples, R.; Lim, G.; Paradies, Y.; McGarty, C. Australians’ Well-Being and Resilience During COVID-19: The Role of Trust, Misinformation, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Locus of Control. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247495

Denson N, Dunn KM, Kamp A, Ben J, Pitman D, Sharples R, Lim G, Paradies Y, McGarty C. Australians’ Well-Being and Resilience During COVID-19: The Role of Trust, Misinformation, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Locus of Control. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(24):7495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247495

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenson, Nida, Kevin M. Dunn, Alanna Kamp, Jehonathan Ben, Daniel Pitman, Rachel Sharples, Grace Lim, Yin Paradies, and Craig McGarty. 2024. "Australians’ Well-Being and Resilience During COVID-19: The Role of Trust, Misinformation, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Locus of Control" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 24: 7495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247495

APA StyleDenson, N., Dunn, K. M., Kamp, A., Ben, J., Pitman, D., Sharples, R., Lim, G., Paradies, Y., & McGarty, C. (2024). Australians’ Well-Being and Resilience During COVID-19: The Role of Trust, Misinformation, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Locus of Control. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(24), 7495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247495