Safety and Effectiveness of G-Mesh® Gynecological Meshes Intended for Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse—A Retrospective Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Procedure

2.2. Patient Population

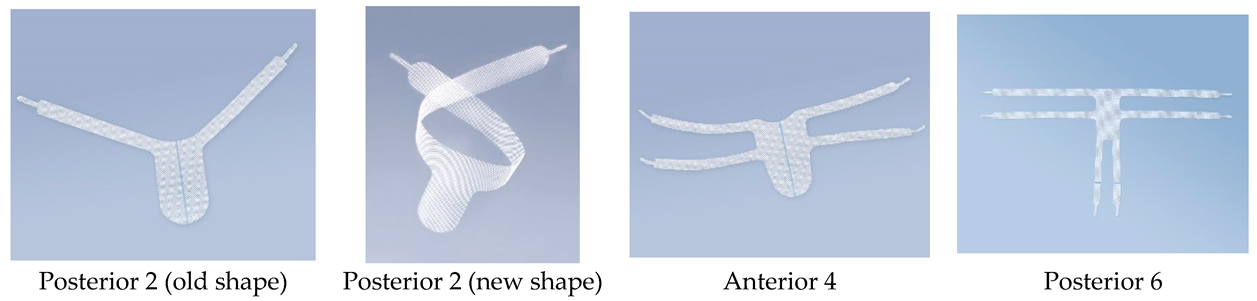

2.3. Description of the Product

- Posterior 2—Make a bilateral incision in the skin in the buttock area. Place the implant in the posterior vaginal wall from the rectum side, with the arms facing upwards, from the sacrospinous ligament. Attach the arms from the sacrospinous ligament and guide their ends through the tissues towards the skin incisions.

- Anterior 4—Make two bilateral incisions in the skin in the groin (upper and lower). Place the implant in the anterior vaginal wall from the bladder side, with the arms facing the obturated openings and with the narrower part (tongue) towards the vaginal opening. Pull the arms through the anterior part and the posterior angle of the obturated openings and guide their ends through the tissues towards the skin incisions. Make the first incision in the area of the genital-femoral line and the second incision 3 cm lower and 2 cm lateral to the first incision.

- Posterior 6—It is possible to cut off the two lateral arms. Make three or two incisions bilaterally (for six or four arms). Make the first incision in the genital-femoral area and pass the first one from the narrower side of the mesh through the anterior part of the obturator holes. Pull the end of the arm through the tissues towards the incisions in the skin. Make the second incision 3 cm lower and 2 cm lateral to the first incision. Pull the second (perpendicular) arm to the second incision through the posterior angle of the obturator hole. Place the implant in the posterior vaginal wall from the rectum side, with the narrower part towards the vaginal opening. Attach the remaining two arms to the sacrospinous ligament and pass through the third opening located in the gluteal area.

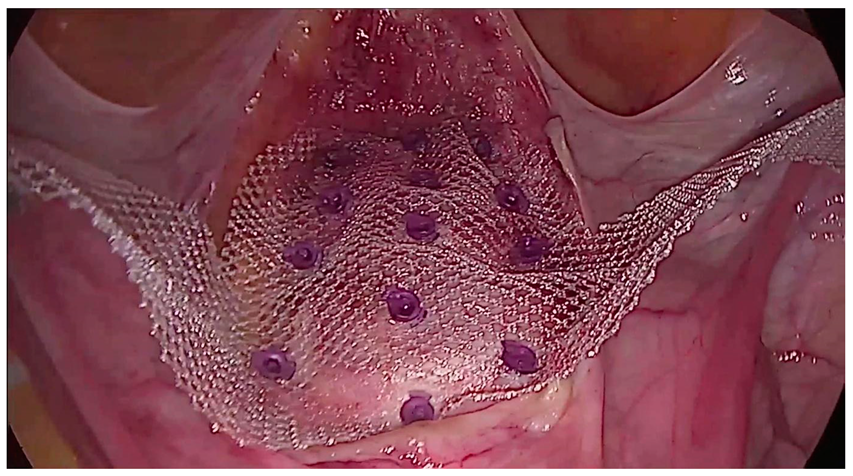

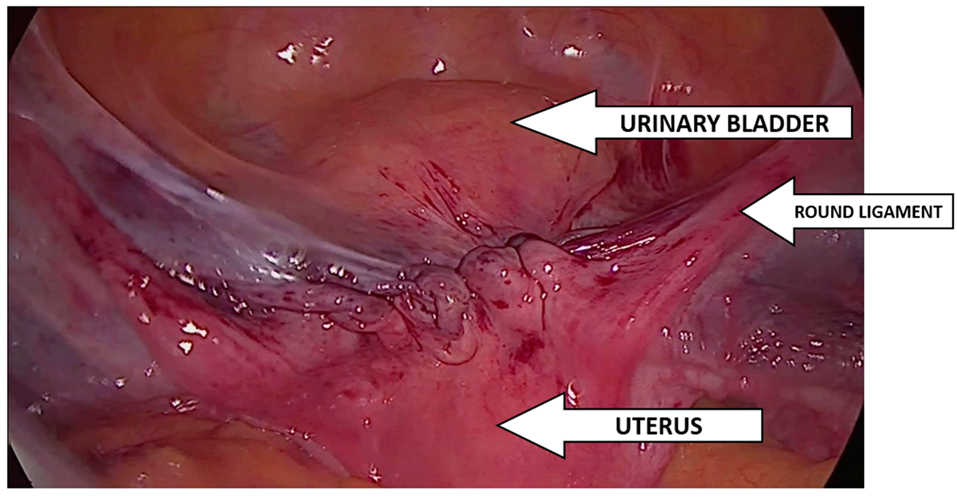

2.4. Implantation Technique

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demography

3.2. Post-Operative Information

3.3. Follow up (Control Visit + Optional Visit)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tim, S.; Mazur-Bialy, A.I. The Most Common Functional Disorders and Factors Affecting Female Pelvic Floor. Life 2021, 11, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pisarska-Krawczyk, M.; Jarząbek-Bielecka, G.; Mizgier, M.; Plagens-Rotman, K.; Friebe, Z.; Kędzia, W. An Outline of the Problem of Pelvic Organ Prolapse, Including Dietary and Physical Activity Prophylaxis; Medical University: Lublin, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann, G.; Börner, C.; Naumann, L.J.; Schröder, S.; Hüsch, T. A novel bilateral anterior sacrospinous hysteropexy technique for apical pelvic organ prolapse repair via the vaginal route: A cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfahmy, A.; Mahran, A.; Conroy, B.; Brewka, R.R.; Ibrahim, M.; Sheyn, D.; El-Nashar, S.A.; Hijaz, A. Abdominal and vaginal pelvic support with concomitant hysterectomy for uterovaginal pelvic prolapse: A comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanowski, P.; Szweda, H.; Szepieniec, W.K.; Malanowska, E.; Świś, E.; Jóźwik, M. Rola Defektu Apikalnego W Patogenezie Obniżenia Narządów Miednicy Mniejszej: Cystocele Z Defektem Apikalnym. Państwo I Społeczeństwo 2017, 4, XVII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliwa, J.; Kryza-Ottou, A.; Grobelak, J.; Domagala, Z.; Zimmer, M. Anterior abdominal fixation—A new option in the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śliwa, J.; Rosner-Tenerowicz, A.; Kryza-Ottou, A.; Ottou, S.; Wiatrowski, A.; Pomorski, M.; Sozański, L.; Zimmer, M. Analysis of prevalence of selected anamnestic factors among women with pelvic organ prolapse. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; Maher, C.; Haya, N.; Crawford, T.J.; Brown, J. Surgery for women with pelvic organ prolapse with or without stress urinary incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD013108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Raba, G.; Dykczyński, P.; Wilczak, M.; Turlakiewicz, K.; Latańska, I.; Sujka, W. Clinical Outcomes of Mid-Urethral Sling (MUS) Procedures for the Treatment of Female Urinary Incontinence: A Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Monist, M.J.; Dobrowolska, B.; Semczuk, A. Pessary-related complications: A brief overview. Gynecol. Pelvic Med. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowski, P.; Gierat, A.; Szweda, H.; Jóźwik, M. Choroby Uroginekologiczne—Poważny Problem Społeczny. Państwo I Społeczeństwo 2017, 4, XVII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ptug.pl/rekomendacje/interdyscyplinarne-wytyczne-polskiego-towarzystwa-uroginekologicznego-odnosnie-diagnostyki-i-leczenia-obnizenia-narzadow-miednicy-mniejszej/ (accessed on 21 September 2014).

- Szymanowski, P. Uroginekologia. Metody Leczenia Operacyjnego. Zawieszenie Boczne Laparoskopowe; Krakowska Akademia im. Andrzeja Frycza Modrzejewskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2021; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dubuisson, J.B.; Chapron, C. Laparoscopic iliac colpo-uterine suspension for treatment of genital prolapse using two meshes. A new operative technique. J. Gynecol. Surg. 1998, 14, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dubuisson, J.B.; Yaron, M.; Wenger, J.M.; Jacob, S. Treatment of genital prolapse by laparoscopic lateral suspension using mesh: A series of 73 patients. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008, 15, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuisson, J.; Eperon, I.; Dällenbach, P.; Dubuisson, J.B. Laparoscopic repair of vaginal vault prolapse by lateral suspension with mesh. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 287, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veit-Rubin, N.; Dubuisson, J.B.; Gayet-Ageron, A.; Lange, S.; Eperon, I.; Dubuisson, J. Patient satisfaction after laparoscopic lateral suspension with mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: Outcome report of a continuous series of 417 patients. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takazawa, N.; Fujisaki, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Tsujimura, A.; Horie, S. Short-term outcomes of the transvaginal minimal mesh procedure for pelvic organ prolapse. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2018, 59, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegre, L.; Debodinance, P.; Demattei, C.; Fabbro Peray, P.; Cayrac, M.; Fritel, X.; Courtieu, C.; Fatton, B.; de Tayrac, R. Clinical evaluation of the Uphold LITE mesh for the surgical treatment of anterior and apical prolapse: A prospective, multicentre trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 2242–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsamo, R.; Illiano, E.; Zucchi, A.; Natale, F.; Carbone, A.; De Sio, M.; Costantini, E. Sacrocolpopexy with polyvinylidene fluoride mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: Mid term comparative outcomes with polypropylene mesh. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 220, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Hu, M.; Dai, F.; Fan, Y.; Deng, Z.; Deng, H.; Cheng, Y. Application of synthetic and natural polymers in surgical mesh for pelvic floor reconstruction. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özant, A.; Arslan, K. Synthetic Meshes in Hernia Surgery. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 2023, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Zhong, C.; Xu, R.; Zou, T.; Wang, F.; Fan, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Novel large-pore lightweight polypropylene mesh has better biocompatibility for rat model of hernia. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2018, 106, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkemichel, M.; Bringman, S.A.W.; Widhe, B.O.O. Long-term Comparison of Recurrence Rates Between Different Lightweight and Heavyweight Meshes in Open Anterior Mesh Inguinal Hernia Repair a Nationwide Population-based Register Study. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciej, W.; Karolina, C.-W.; Katarzyna, T.; Adam, M.; Magdalena, M.; Małgorzata, K. Uteropeksja boczna techniką Dubuissona. In Ginekologia Operacyjna; Stojko, R., Samulak, D., Eds.; PZWL Wydaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini, T.; Panattoni, A.; Cadenbach-Blome, T.; Caiazzo, N.; García, M.C.; Caretto, M.; Chun, F.; Francescangeli, E.; Gaia, G.; Giannini, A.; et al. Role of lateral suspension for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: A Delphi survey of expert panel. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 4344–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, E.M.; Hehenkamp, W.J.; Geomini, P.M.; Janssen, P.F.; Jansen, F.W.; Twijnstra, A.R. Laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications: Clinical practice guideline. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 296, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelak, W. Analiza Czynników Mających Wpływ na Jakość Świadczeń Zdrowotnych w Ginekologii Operacyjnej. Ph.D. Thesis, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznań, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.F.; Feiner, B.; DeCuyper, E.M.; Nichlos, C.J.; Hickey, K.V.; O’Rourke, P. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy versus total vaginal mesh for vaginal vault prolapse: A randomized trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 360.e1–360.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, V.; Hengrasmee, P.; Lam, A.; Luscombe, G.; Lawless, A.; Lam, J. Evidence to justify retention of transvaginal mesh: Comparison between laparoscopic sacral colpopexy and transvaginal Elevate™ mesh. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withagen, M.I.; Vierhout, M.E.; Milani, A.L.; Mannaerts, G.H.; Kluivers, K.B.; van der Weiden, R.M. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy versus total vaginal mesh for vault prolapse; comparison of cohorts. Gynecol. Surg. 2013, 10, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration: FDA. Safety Communication: Update on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse; U. S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Springs, MD, USA, 2011. Available online: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm (accessed on 13 July 2013).

- Heinonen, P.; Aaltonen, R.; Joronen, K. i wsp.: Long-term outcome after transvaginal mesh repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration: FDA. Strengthens Requirements for Surgical Mesh for the Transvaginal Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse to Address Safety Risks; U. S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Springs, MD, USA, 2016. Available online: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm479732.htm (accessed on 4 January 2016).

- Schimpf, M.O.; Abed, H.; Sanses, T. i wsp.: Graft and mesh use in transvaginal prolapse repair: A systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 28, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K. i wsp.: Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD012079. [Google Scholar]

- Mereu, L.; Tateo, S.; D’Alterio, M.N.; Russo, E.; Giannini, A.; Mannella, P.; Pertile, R.; Cai, T.; Simoncini, T. Laparoscopic lateral suspension with mesh for apical and anterior pelvic organ prolapse: A prospective double center study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 244, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziioannidou, K.; Veit-Rubin, N.; Dällenbach, P. Laparoscopic lateral suspension for anterior and apical prolapse: A prospective cohort with standardized technique. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshankiti, H.; Houlihan, S.; Robert, M.; Calgary Women’s Pelvic Health Research Group. Incidence and contributing factors of perioperative complications in surgical procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasyan, G.; Abramyan, K.; Popov, A.A.; Gvozdev, M.; Pushkar, D. Mesh–related and intraoperative complications of pelvic organ prolapse repair. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2014, 67, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buca DI, P.; Liberati, M.; Falò, E.; Leombroni, M.; Di Giminiani, M.; Di Nicola, M.; Santarelli, A.; Frondaroli, F.; Fanfani, F. Long-term outcome after surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse with Elevate Prolapse Repair System. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 38, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu Arrom, L.; Errando Smet, C.; Gutierrez Ruiz, C.; Araño, P.; Palou Redorta, J. Pelvic organ prolapse repair with mesh: Mid-term efficacy and complications. Urol. Int. 2018, 101, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh Type | Arm Span (mm) | Arm Length | Arm Width |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior 2 (old version) | 574 | - | 32 |

| Posterior 2 (new version) | 574 | 262 | 32 |

| Anterior 4 | 418 | 174 | 15 |

| Posterior 4 | 600 | 266 (lateral arm) | 17 |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 66) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 15) | p Values | All Patients (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (range) | 62 (28–81) | 64 (38–83) | 0.2643 | 62 (28–83) |

| BMI | 25.53 (19.33–38) | 25.61 (17.97–33.46) | 0.2563 | 26 (18–38) |

| Medical history | 0.9219 | |||

| Thyroid diseases | 17 (25.8%) | 4 (26.7%) | 21 (25.9%) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (4.9%) | |

| Urinary diseases | 6 (9.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | 8 (9.9%) | |

| Digestive system diseases | 7 (10.6%) | 1 (6.7%) | 8 (9.9%) | |

| Respiratory system diseases | 3 (4.5%) | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 6 (9.1%) | 0 | 6 (7.4%) | |

| Cerebral diseases | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Skin diseases | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Vascular diseases | 7 (10.6%) | 2 (13.3%) | 9 (11.1%) | |

| Bone diseases | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Diseases of the reproductive system | 7 (10.6%) | 3 (20.0%) | 10 (12.3%) | |

| Neurological disorders | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Diseases of the visual system | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (4.9%) | |

| Metabolic diseases | 39 (59.1%) | 11 (73.3%) | 50 (61.7%) | |

| Hernia surgery | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Clinical condition | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Mental disorders | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) | 5 (7.4%) | 2 (15.4%) | 7 (8.6%) | |

| Overactive bladder (OAB) | 4 (5.9%) | 0 | 4 (4.9%) | |

| None | 14 (20.6%) | 1 (7.7%) | 15 (18.5%) | |

| Medication intake | 1.0000 | |||

| yes | 48 (70.6%) | 11 (84.6%) | 60 (74.1%) | |

| no | 20 (29.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 21 (25.9%) |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 66) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 15) | p Values | All Patients (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of disorder | 0.0113 | |||

| lowering of the anterior vaginal wall/urinary bladder (Cystocele) | 62 (93.9%) | 13 (86.7%) | 75 (92.6%) | |

| lowering or prolapse of the uterus (Uterine prolapse) | 51 (77.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 55 (67.9%) | |

| lowering of the vaginal vault/urethra (Ureterocele) | 5 (7.6%) | 1 (6.7%) | 6 (7.4%) | |

| lowering of the posterior vaginal/rectal wall (Rectocele) | 41 (62.1%) | 4 (26.7%) | 45 (55.6%) | |

| lowering of the uterorectal cavity/small intestine (Enterocele) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gynecological examination | 0.0297 | |||

| Post-hysterectomy (including/excluding appendages) | 0 | 7 (46.7%) | 7 (8.6%) | |

| Post-Dubuisson surgery | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Post- anterior/posterior surgery | 0 | 3 (20%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Urogynecologycal examination | 0.0468 | |||

| Bladder POPQ into front vaginal wall | ||||

| level I | 5(33.3%) | 0 | 5 (6.2%) | |

| level II | 20 (30.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 24(29.6%) | |

| level III | 25 (37.9%) | 7 (46.7%) | 32 (39.5%) | |

| level IV | 11 (16.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 14 (17.3%) | |

| Rectum POPQ into back vaginal wall | ||||

| level 0 | 15 (22.7%) | 5(33.3%) | 20(24.7%) | |

| level II | 21(31.8%) | 4 (26.7%) | 25(30.9%) | |

| level III | 11 (16.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 12 (14.8%) | |

| level IV | 3 (4.5%) | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Cervix POPQ | ||||

| level 0 | 7 (10.6%) | 3(20%) | 10 (12.3%) | |

| level II | 18 (27.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 20 (24.7%) | |

| level III | 17 (25.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | 18 (22.2%) | |

| level IV | 13 (19.7%) | 0 | 13 (16.0%) | |

| Cough test | 0.0039 | |||

| negative | 2 (3.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 5 (6.2%) | |

| no data | 64 (97%) | 12 (80.0%) | 76 (93.8%) |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 66) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 15) | p Values | All Patients (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of products used | 0.0572 | |||

| Posterior 2 old | 3 (4.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (6.2%) | |

| Posterior 2 new | 63 (95.5%) | 0 | 63 (77.8%) | |

| Anterior 4 | 0 | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Posterior 6 | 0 | 11 (73.3%) | 11 (13.6%) | |

| Surgery time in minutes (range) | 83 (50–201) | 85 (70–190) | 0.0010 | 83 (50–201) |

| Perioperative complications | 1.0000 | |||

| tightening of the postoperative wound on the right side | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| problems with dissecting the bladder from the vagina–scars after anterior surgery | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Implant-related adverse events | 0 | 0 | - | 0 |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 66) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 15) | p Values | All Patients (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean hospitalization time in days (range) | 3 (1–4) | 3 (3–5) | 0.0014 | 3 (1–5) |

| Use of antibiotics | 1.0000 | |||

| Yes | 55 (83.3%) | 13 (86.7%) | 68 (84.0%) | |

| No | 11 (16.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 13 (16.0%) | |

| Complications in first days post surgery | 0.0000 | |||

| recurring cystocele/rectocele | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| pain at the laparoscopic puncture site | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Adverse events related to the implant | 0 | 0 | - | 0 |

| Mesh-related comfort/discomfort assessment | 0.0000 | |||

| very good | 65 (98.5%) | 14 (93.3%) | 79 (98.0%) | |

| good | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| no data | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Mean pain assessment VAS (1–10) | 0.0000 | |||

| 0 | 66 (100%) | 13 (86.7%) | 79 (97.5%) | |

| 2 | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Function/disfunction assessment | 0.0000 | |||

| very good | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| good | 64 (97.0%) | 11 (73.3%) | 75 (92.6%) | |

| no data | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (3.7%) |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 66) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 15) | p Values | All Patients (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up in days (range) | 79 (22–429) | 63 (6–181) | 0.0118 | 76 (6–429) |

| Complications | 1.0000 | |||

| related to urinary tract | 17 (25.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | 18 (22.2%) | |

| post-operative pain | 26 (39.4%) | 1 (6.7%) | 27 (33.3%) | |

| de novo pelvic organ prolapse | 23 (34.8%) | 0 | 23 (28.4%) | |

| constipation | 4 (6.1%) | 0 | 4 (4.9%) | |

| recurrent vaginal infections | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| difficulties in passing stool | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| wound infection | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| discomfort in rectal region | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| qualification for TOT surgery | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Adverse events | 0 | 0 | - | 0 |

| Effectiveness | 0.0000 | |||

| very good | 60 (90.9%) | 15 (100%) | 75 (92.6%) | |

| good | 3 (4.5%) | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | |

| poor | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| no data | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Comfort | 0.0000 | |||

| very good | 60 (90.9%) | 15 (100%) | 75 (92.6%) | |

| good | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| poor | 3 (4.5%) | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | |

| no data | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Mean pain sensation VAS (1–10) | 0.0006 | |||

| 0 | 58 (87.5%) | 15 (100%) | 73 (90.1%) | |

| 2 | 4 (6.1%) | 0 | 4 (4.9%) | |

| 4 | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.0%) | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | |

| Function/dysfunction assessment | 0.0000 | |||

| very good | 8 (12.1%) | 1 (6.7%) | 9 (11.1%) | |

| good | 56 (84.8%) | 13 (86.7%) | 69 (85.2%) | |

| poor | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| no data | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Foreign body sensation | 0.3148 | |||

| yes | 7 (10.6%) | 1 (6.7%) | 8 (9.9%) | |

| no | 54 (81.8%) | 12 (80.0%) | 66 (81.5%) | |

| no data | 5 (7.6%) | 2 (13.3%) | 7 (8.6%) |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 38) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 4) | p Values | All Patients (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up in days (range) | 175 (49–429) | 213 (81–336) | 0.0000 | 178 (49–429) |

| Complications | 1.0000 | |||

| post TOT-surgery | 0 | 1 (25%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| overactive bladder | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| vaginal itchiness | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| chronic postoperative pain—lower abdominal pain | 6 (15.8%) | 0 | 6 (14.3%) | |

| stress urinary incontinence | 5 (13.2%) | 0 | 5 (11.9%) | |

| pelvic organ prolapse | 3 (7.9%) | 0 | 3 (7.1%) | |

| chronic pain at implantation site | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| constipation | 3 (7.9%) | 0 | 3 (7.1%) | |

| feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| pulling sensation at passing stool | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| recurrent rectocele | 12 (31.6%) | 0 | 12 (28.6%) | |

| recurrent cystocele | 4 (10.5%) | 0 | 4 (9.5%) | |

| cervix elongation | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| pulling sensation in bladder area | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| nycturia | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| pelvic heaviness | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| bulging in vagina | 3 (7.9%) | 0 | 3 (7.1%) | |

| fecal incontinence | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| micturition disorder | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 2 (4.8%) | |

| dyspareunia | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| vaginal dryness | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| fungal infection | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| recurrent enterocele | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| pulling sensation at implantation site | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| total vaginal and uterine prolapse | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| none | 16 (38.1%) | 16 (38.1%) | ||

| Adverse events | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | - | 2 (4.8%) |

| none | 39 (92.9%) | 39 (92.9%) | ||

| no data | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.4%) | ||

| Efficiency | 0.0324 | |||

| very good | 26 (68.4%) | 4 (100%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

| good | 8 (21.1%) | 0 | 8 (19.0%) | |

| poor | 3 (7.9%) | 0 | 3 (7.1%) | |

| no data | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Comfort | 0.0354 | |||

| very good | 33 (86.8%) | 4 (100%) | 37 (88.1%) | |

| good | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| poor | 4 (10.5%) | 0 | 4 (9.5%) | |

| no data | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Mean pain sensation VAS (1–10) | 0.000 | |||

| 0 | 31 (81.6%) | 4 (100%) | 35 (83.3%) | |

| 2 | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 2 (4.8%) | |

| 3 | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| 4 | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| 5 | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 2 (4.8%) | |

| no data | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Function/dysfunction assessment | 0.0018 | |||

| very good | 8 (21.1%) | 2 (50%) | 10 (23.8%) | |

| good | 26 (68.4%) | 1 (25%) | 27 (64.3%) | |

| poor | 4 (10.5%) | 0 | 4 (9.5%) | |

| no data | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Foreign body sensation | 1.0000 | |||

| yes | 10 (26.3%) | 0 | 10 (23.8%) | |

| no | 27 (71.1%) | 2 (50%) | 29 (69.0%) | |

| no data | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (50%) | 3 (7.1%) | |

| Patients with Laparoscopic Procedures (n = 66) | Patients with Other Surgeries (n = 15) | p Values | All Patients (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up in days (range) | 321 (135–1430) | 440 (138–1430) | 0.0000 | 318 (135–1430) |

| Comfort | 0.0587 | |||

| very good | 56 (84.8%) | 12 (80.0%) | 68 (84.0%) | |

| good | 2 (3.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 5 (6.2%) | |

| poor | 3 (4.5%) | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | |

| no data | 5 (7.6%) | 0 | 5 (6.2%) | |

| Mean pain sensation VAS (1–10) | 0.0000 | |||

| no data | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| 0 | 57 (86.4%) | 15 (100%) | 72 (88.9%) | |

| 2 | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| 3 | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| 4 | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| 5 | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (1.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilczak, M.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Wójtowicz, M.; Kądziołka, P.; Paul, P.; Gajdzicka, A.; Jezierska, K.; Sujka, W. Safety and Effectiveness of G-Mesh® Gynecological Meshes Intended for Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse—A Retrospective Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7421. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237421

Wilczak M, Chmaj-Wierzchowska K, Wójtowicz M, Kądziołka P, Paul P, Gajdzicka A, Jezierska K, Sujka W. Safety and Effectiveness of G-Mesh® Gynecological Meshes Intended for Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse—A Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(23):7421. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237421

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilczak, Maciej, Karolina Chmaj-Wierzchowska, Mariusz Wójtowicz, Przemysław Kądziołka, Paulina Paul, Aleksandra Gajdzicka, Kaja Jezierska, and Witold Sujka. 2024. "Safety and Effectiveness of G-Mesh® Gynecological Meshes Intended for Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse—A Retrospective Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 23: 7421. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237421

APA StyleWilczak, M., Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K., Wójtowicz, M., Kądziołka, P., Paul, P., Gajdzicka, A., Jezierska, K., & Sujka, W. (2024). Safety and Effectiveness of G-Mesh® Gynecological Meshes Intended for Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse—A Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7421. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237421