Depression and Anxiety in 336 Elective Orthopedic Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

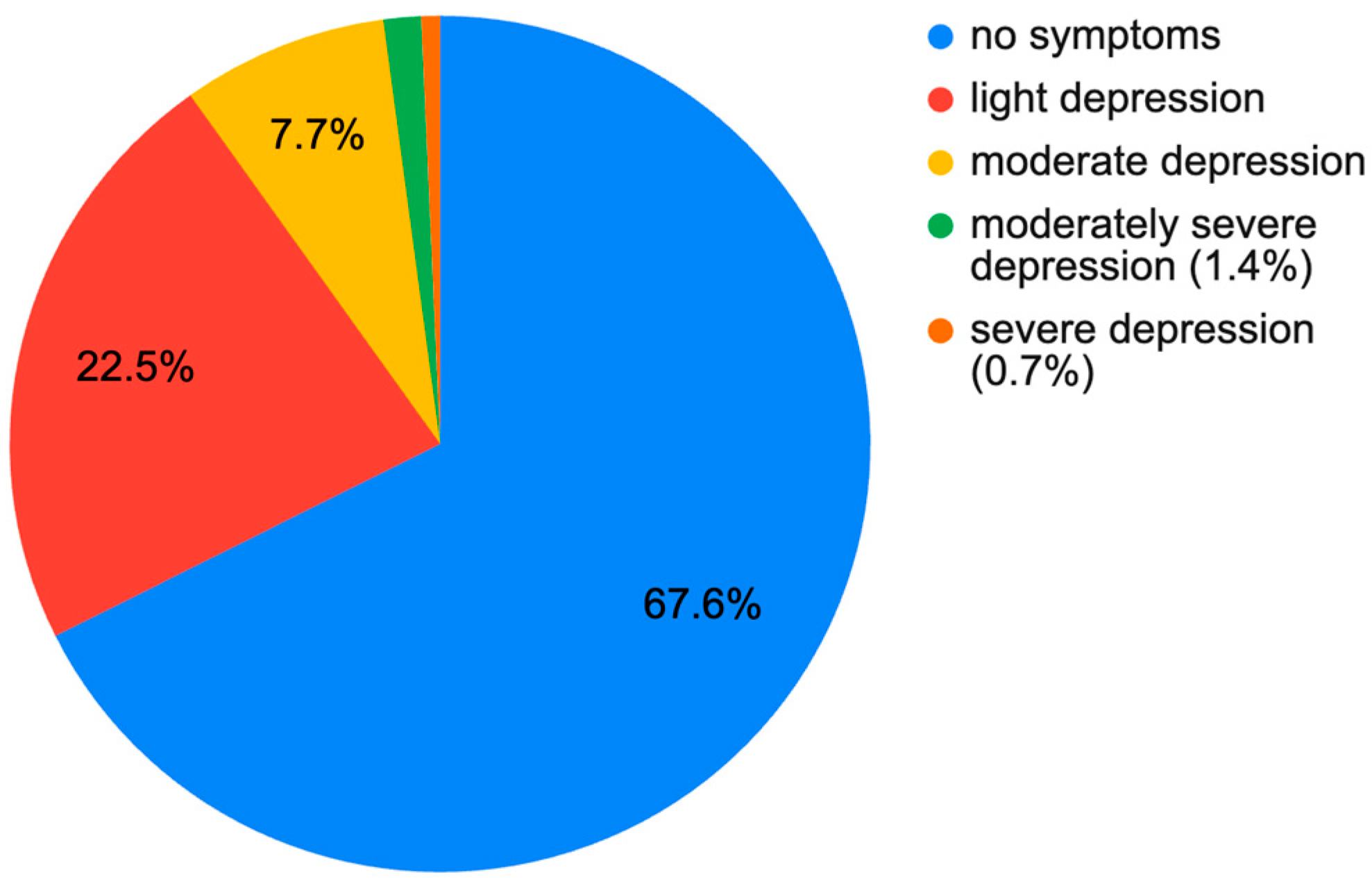

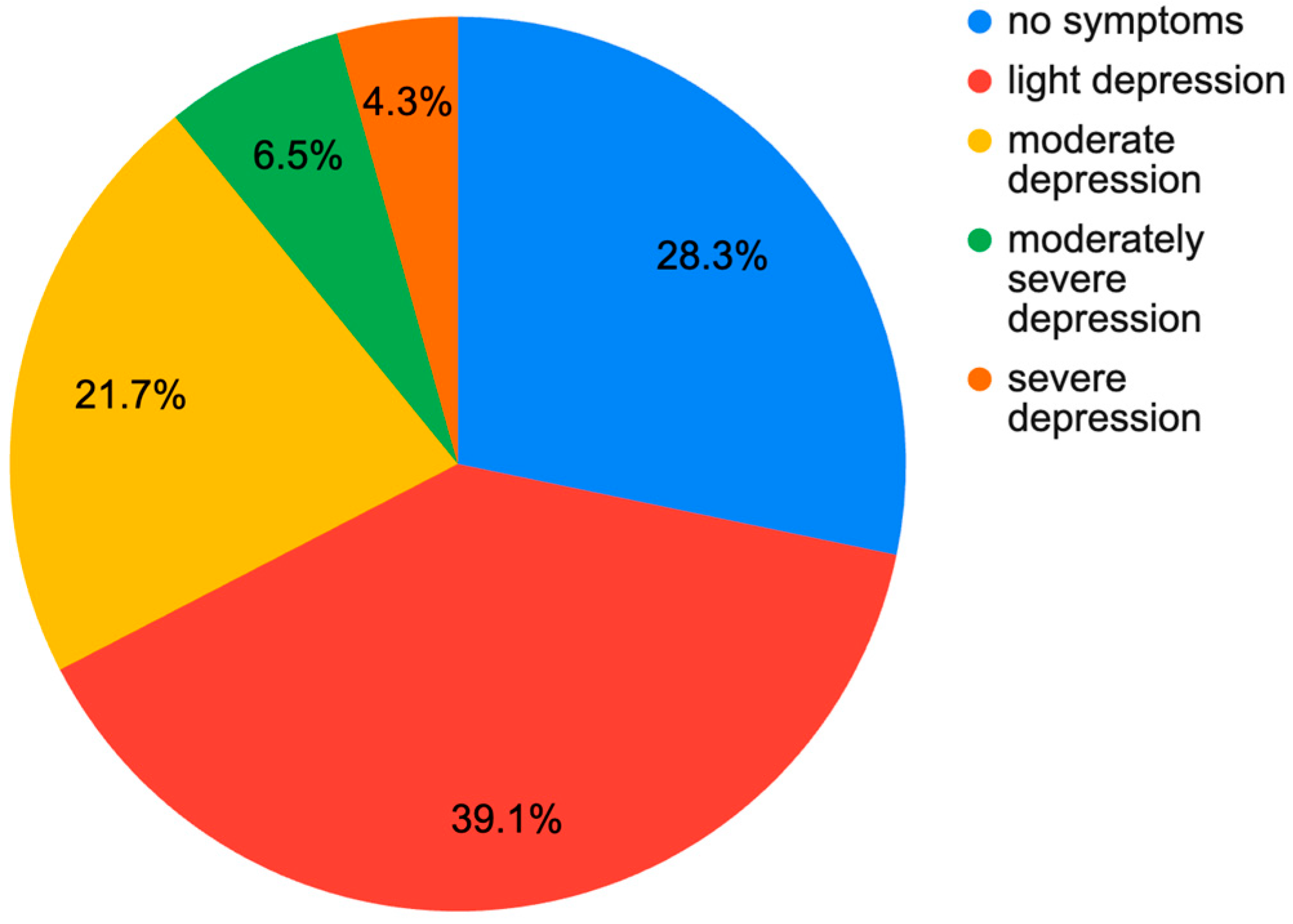

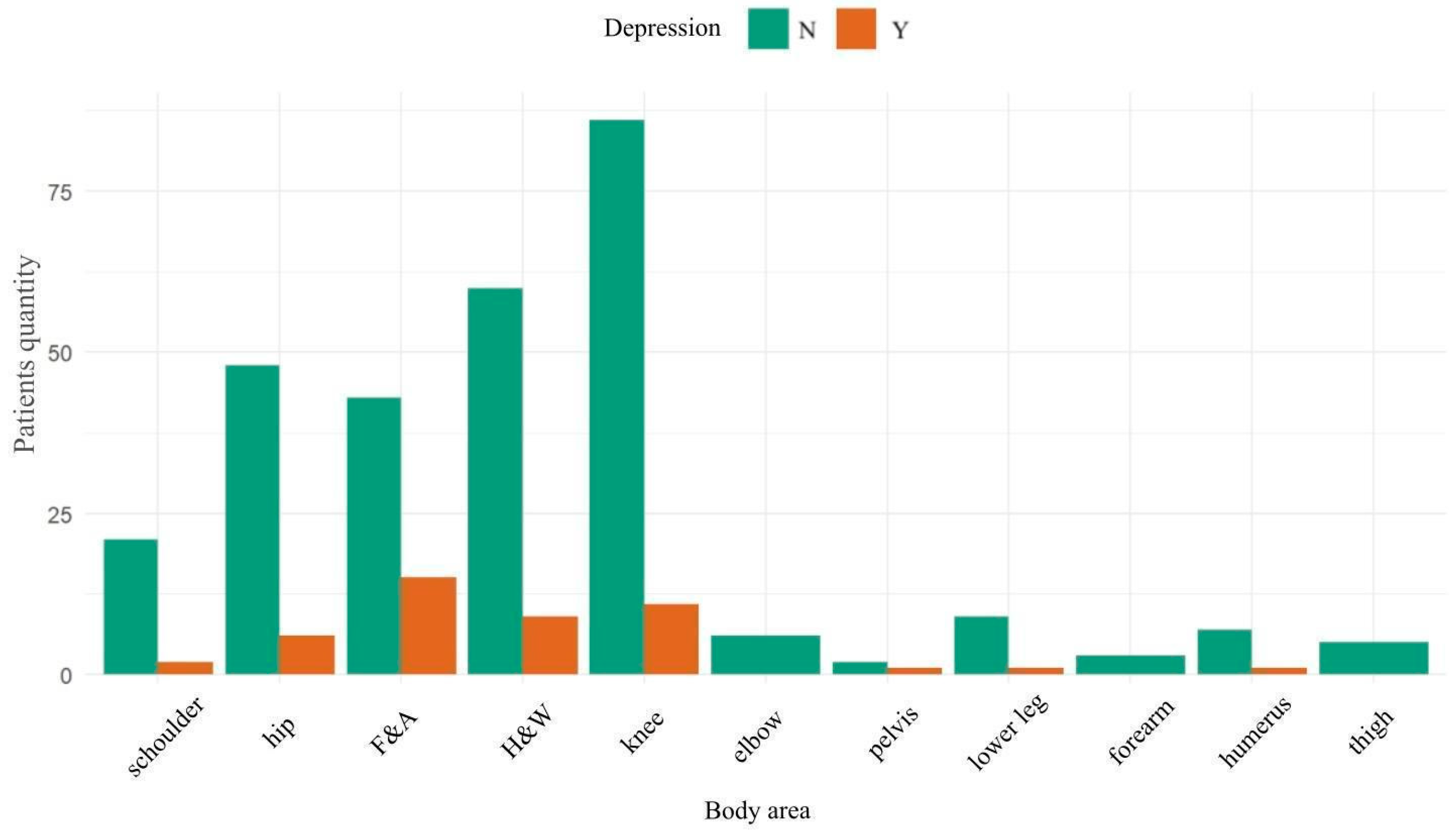

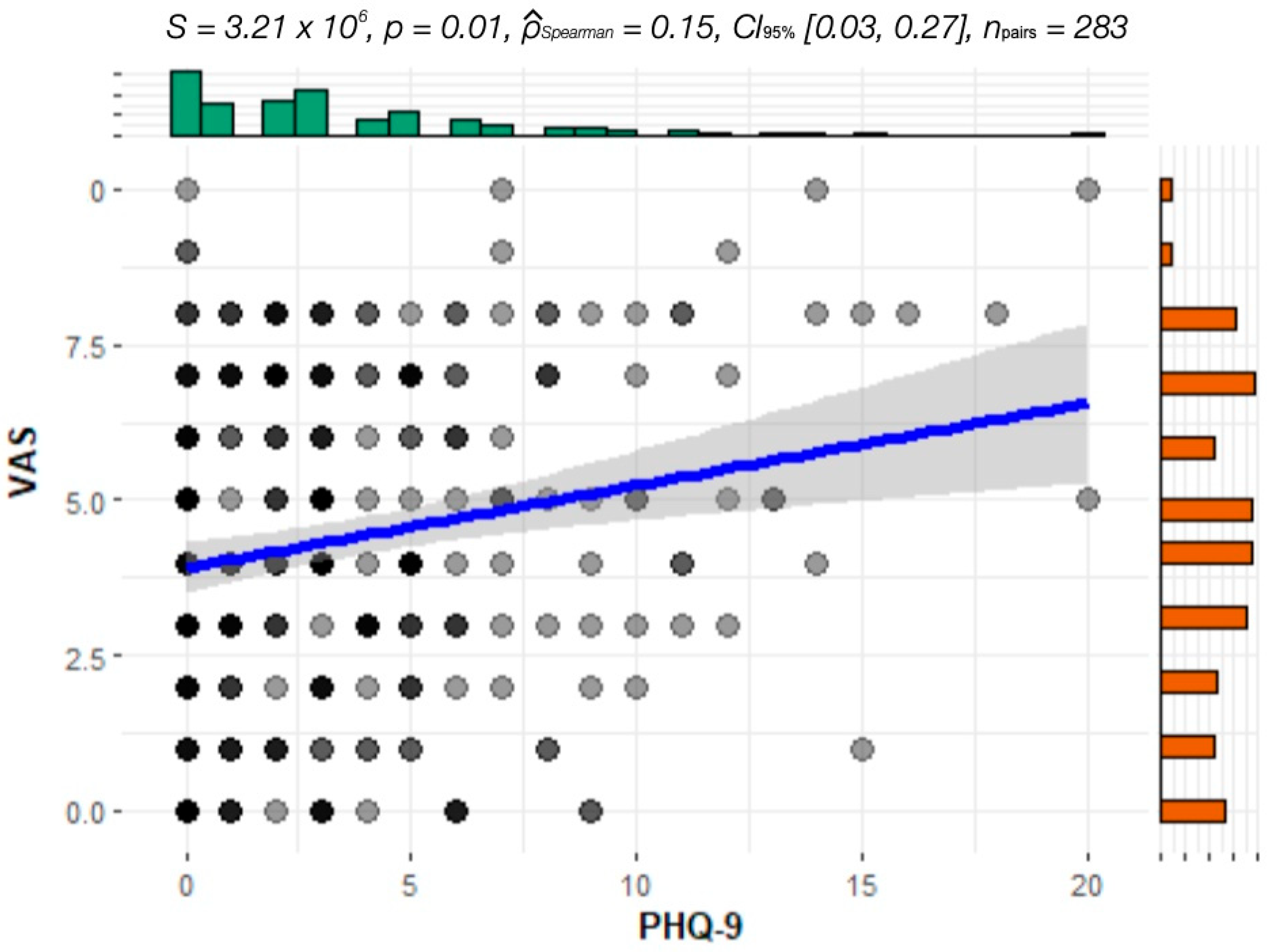

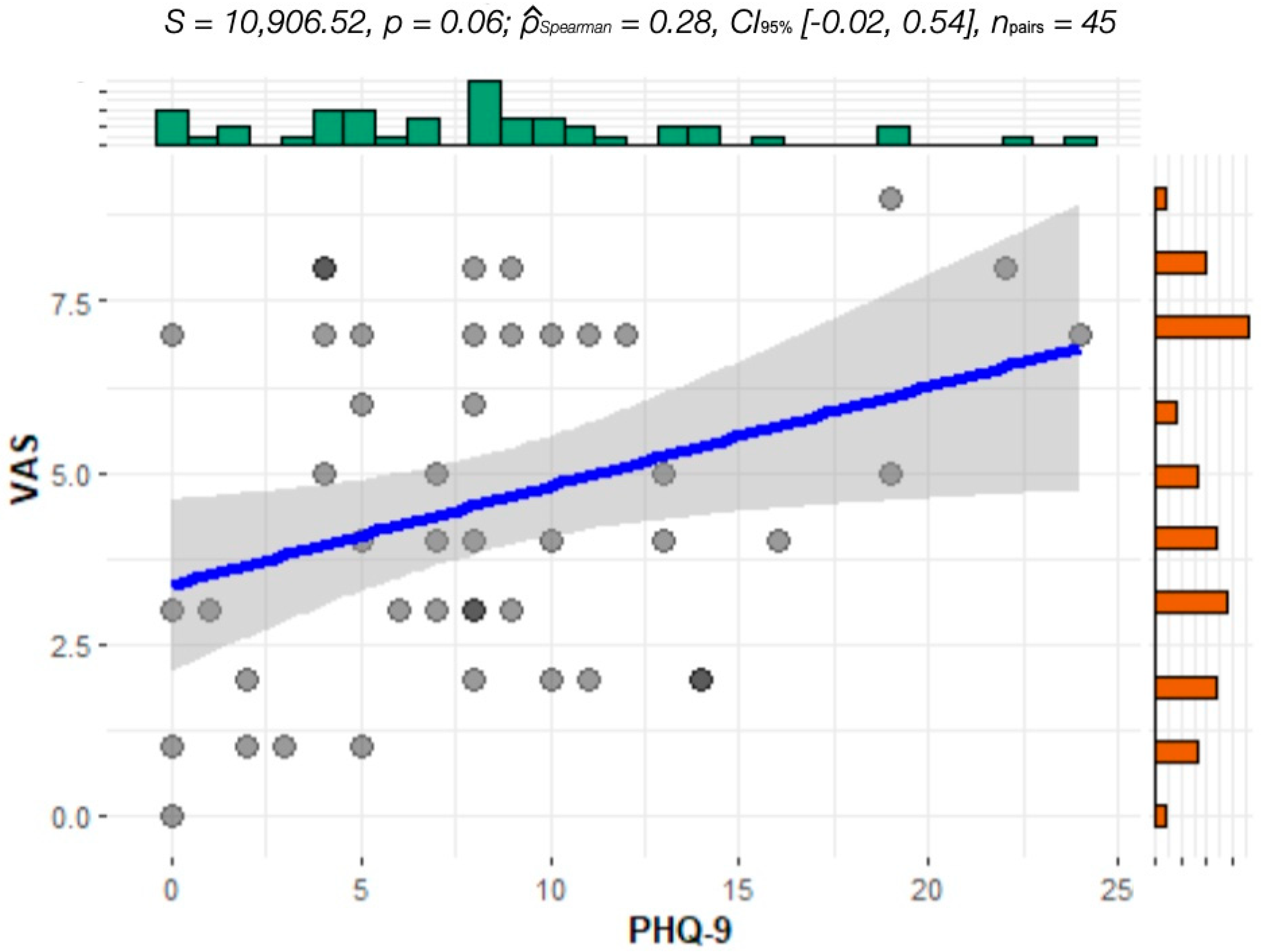

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Q.; Huang, S.; Xu, H.; Peng, J.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, L.; et al. The Burden of Mental Disorders in Asian Countries, 1990–2019: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD Results. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Muñoz-Navarro, R.; Cano-Vindel, A.; Medrano, L.A.; Schmitz, F.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, P.; Abellán-Maeso, C.; Font-Payeras, M.A.; Hermosilla-Pasamar, A.M. Utility of the PHQ-9 to Identify Major Depressive Disorder in Adult Patients in Spanish Primary Care Centres. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambamoorthi, U.; Shah, D.; Zhao, X. Healthcare Burden of Depression in Adults with Arthritis. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2017, 17, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, R.; Daniel, J.-P.A.; Idarraga, A.J.; Perticone, K.M.; Lin, J.; Holmes, G.B.; Lee, S.; Hamid, K.S.; Bohl, D.D. Depression Following Operative Treatments for Achilles Ruptures and Ankle Fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2021, 42, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscatelli, S.; Spurr, H.; O’Hara, N.N.; O’Hara, L.M.; Sprague, S.A.; Slobogean, G.P. Prevalence of Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Acute Orthopaedic Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Trauma 2017, 31, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekes, D.G.; Campbell, R.E.; Shi, W.J.; Giunta, N.; Freedman, K.B.; Pepe, M.D.; Tucker, B.S.; Tjoumakaris, F.P. Prevalence of Clinical Depression Among Patients After Shoulder Stabilization: A Prospective Study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2019, 101, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattas, S.A.; Smith, T.; Bhatti, M.; Wilson-Nunn, D.; Donell, S. Greater Pre-Operative Anxiety, Pain and Poorer Function Predict a Worse Outcome of a Total Knee Arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 3403–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.K.; Barth, K.; Cororaton, A.; Hummel, A.; Cody, E.A.; Mancuso, C.A.; Ellis, S. Association of Depression and Anxiety with Expectations and Satisfaction in Foot and Ankle Surgery. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 29, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, T.J.; Bernstein, D.N.; Merchan, N.; Franco, J.; Nessralla, C.J.; Harper, C.M.; Rozental, T.D. The Association Between Depression and Antidepressant Use and Outcomes After Operative Treatment of Distal Radius Fractures at 1 Year. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2022, 47, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, D.T.; Gevers Deynoot, B.D.J.; Stufkens, S.A.; Sierevelt, I.N.; Goslings, J.C.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; Doornberg, J.N. What Factors Are Associated with Outcomes Scores After Surgical Treatment Of Ankle Fractures with a Posterior Malleolar Fragment? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2019, 477, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagrave, K.G.; Lewin, A.M.; Harris, I.A.; Badge, H.; Naylor, J. Association Between Pre-Operative Anxiety and/or Depression and Outcomes Following Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 29, 2309499021992605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajapey, S.P.; McKeon, J.F.; Krueger, C.A.; Spitzer, A.I. Outcomes of Total Joint Arthroplasty in Patients with Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 18, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crijns, T.J.; Bernstein, D.N.; Gonzalez, R.; Wilbur, D.; Ring, D.; Hammert, W.C. Operative Treatment Is Not Associated with More Relief of Depression Symptoms than Nonoperative Treatment in Patients with Common Hand Illness. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020, 478, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Regular Physical Exercise and Its Association with Depression: A Population-Based Study Short Title: Exercise and Depression. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 309, 114406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, H.; Suen, Y.N.; Hui, C.L.M.; Wong, S.M.Y.; Chan, S.K.W.; Lee, E.H.M.; Wong, M.T.H.; Chen, E.Y.H. Assessing Anxiety among Adolescents in Hong Kong: Psychometric Properties and Validity of the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) in an Epidemiological Community Sample. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Rief, W.; Klaiberg, A.; Braehler, E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the General Population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2006, 28, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, S.F.; Hashim, I.J.; Hashim, M.J.; Stip, E.; Samad, M.A.; Ahbabi, A.A. Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders: Global Burden and Sociodemographic Associations. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NFZ o Zdrowiu. Depresja. Available online: https://ezdrowie.gov.pl/portal/home/badania-i-dane/zdrowe-dane/raporty/nfz-o-zdrowiu-depresja (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Villarroel, M.A.; Terlizzi, E.P. Symptoms of Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019; NCHS Data Brief No. 379; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Nakagawa, R.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kimura, S.; Sadamasu, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sato, Y.; Akagi, R.; Sasho, T.; Ohtori, S. Association of Anxiety and Depression with Pain and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Foot and Ankle Diseases. Foot Ankle Int. 2017, 38, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awale, A.; Dufour, A.B.; Katz, P.; Menz, H.B.; Hannan, M.T. Link Between Foot Pain Severity and Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.M.; Shih, C.-D.; Brooks, B.M.; Tower, D.E.; Tran, T.T.; Simon, J.E.; Armstrong, D.G. The Diabetic Foot-Pain-Depression Cycle. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2023, 113, 22–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.-H.; Liu, X.-M.; Yu, H.-R.; Qian, Y.; Chen, H.-L. The Incidence of Depression in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2022, 21, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maydick, D.R.; Acee, A.M. Comorbid Depression and Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Home Healthc. Now. 2016, 34, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavipour, F.; Rahemi, Z.; Sadat, Z.; Ajorpaz, N.M. The Effects of Foot Reflexology on Depression during Menopause: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-L.; Hung, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-R.; Chen, K.-H.; Yang, S.-N.; Chu, C.-M.; Chan, Y.-Y. Effect of Foot Reflexology Intervention on Depression, Anxiety, and Sleep Quality in Adults: A Meta-Analysis and Metaregression of Randomized Controlled Trials. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 2654353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H. The Link between Depression and Physical Symptoms. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Halawi, M.J.; Gronbeck, C.; Savoy, L.; Cote, M.P.; Lieberman, J.R. Depression Treatment Is Not Associated with Improved Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Total Joint Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2020, 35, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekar, A.A.; Hendrix, J.M.; Cascella, M. WHO Analgesic Ladder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Sánchez-Salcedo, J.A.; Estevez-Cabrera, M.M.; Molina-Jiménez, T.; Cortes-Altamirano, J.L.; Alfaro-Rodríguez, A. Depression and Pain: Use of Antidepressants. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Total N = 336 | F&A N = 58 | H&W N = 69 | Shoulder N = 23 | Hip N = 54 | Knee N = 97 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 1 | 56.0 (41.0, 67.0) | 57.0 (42.0, 63.8) | 51.0 (41.0, 65.0) | 55.0 (40.5, 61.0) | 65.5 (55.3, 71.0) | 55.0 (38.0, 69.0) |

| Female | 193 (57.4%) | 40 (69.0%) | 42 (60.9%) | 9 (39.1%) | 25 (46.3%) | 54 (55.7%) |

| Male | 143 (42.6%) | 18 (31.0%) | 27 (39.1%) | 14 (60.9%) | 29 (53.7%) | 43 (44.3%) |

| BMI 1,2 | 27.1 (24.0, 30.3) | 26.5 (23.2, 29.1) | 25.5 (23.2, 28.8) | 26.5 (22.5, 29.1) | 27.4 (24.2, 30.5) | 27.8 (25.6, 31.8) |

| Treated depression (N) | 46 (13.7%) | 15 (25.9%) | 9 (13.0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 6 (11.1%) | 11 (11.3%) |

| PHQ-9 1 | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.3, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 6.5) | 3.0 (0.3, 6.8) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) |

| VAS 1 | 4.0 (2.8, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (2.3, 5.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 7.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) |

| GAD-7 1 | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.5, 5.5) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 4.3) |

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: 20–29 | 0.23 | 0.01, 1.24 | 0.2 |

| Gender: Male | 0.37 | 0.15, 0.83 | 0.021 |

| Body area: F&A | 3.24 | 1.42, 7.24 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuik, L.; Łuczkiewicz, P. Depression and Anxiety in 336 Elective Orthopedic Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237354

Kuik L, Łuczkiewicz P. Depression and Anxiety in 336 Elective Orthopedic Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(23):7354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237354

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuik, Leszek, and Piotr Łuczkiewicz. 2024. "Depression and Anxiety in 336 Elective Orthopedic Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 23: 7354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237354

APA StyleKuik, L., & Łuczkiewicz, P. (2024). Depression and Anxiety in 336 Elective Orthopedic Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237354