Comment on Cancello et al. Sarcopenia Prevalence Among Hospitalized Patients with Severe Obesity: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2880

Abstract

1. Introduction

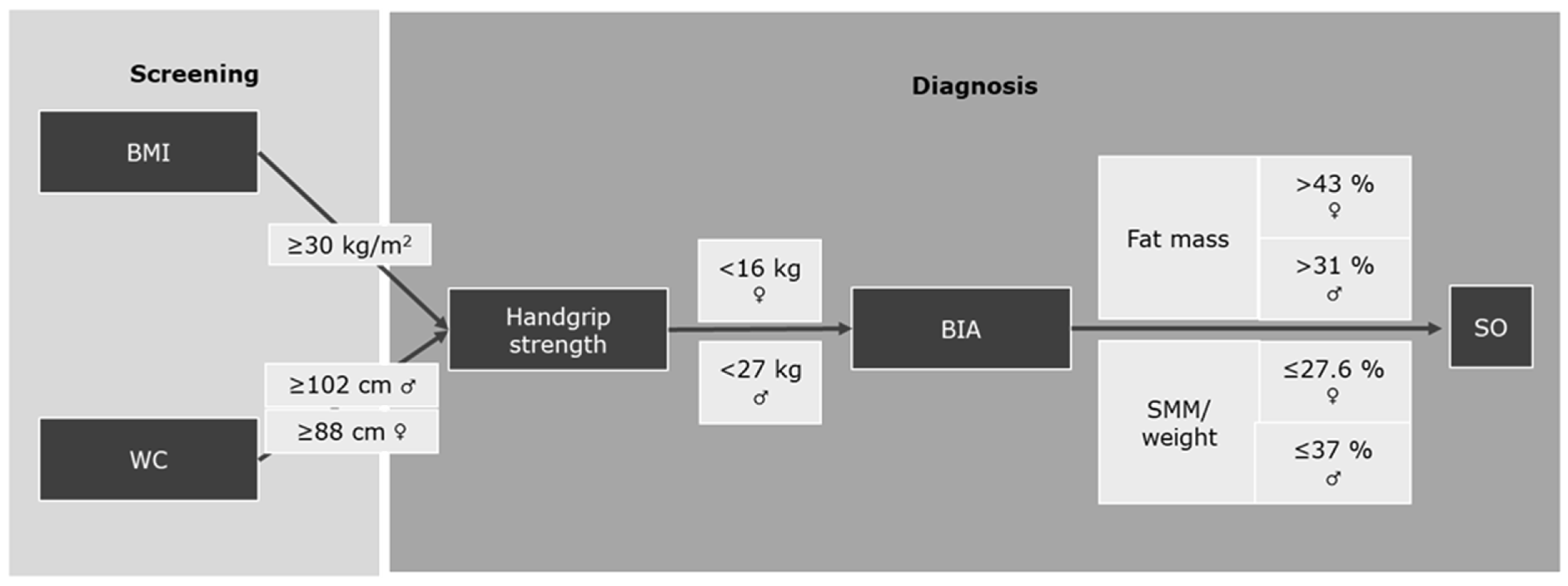

2. How Is Sarcopenic Obesity Diagnosed?

3. High Fat Mass and Reduced SMM/Weight Are Necessary for the Diagnosis of SO

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prado, C.M.; Batsis, J.A.; Donini, L.M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Siervo, M. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: A clinical overview. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batsis, J.A.; Villareal, D.T. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: Aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 513–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D.; et al. Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Sarcopenic Obesity: ESPEN and EASO Consensus Statement. Obes. Facts 2022, 15, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schluessel, S.; Huemer, M.T.; Peters, A.; Drey, M.; Thorand, B. Sarcopenic obesity using the ESPEN and EASO consensus statement criteria of 2022—Results from the German KORA-Age study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 17, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Someya, Y.; Tamura, Y.; Kaga, H.; Sugimoto, D.; Kadowaki, S.; Suzuki, R.; Aoki, S.; Hattori, N.; Motoi, Y.; Shimada, K.; et al. Sarcopenic obesity is associated with cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults: The Bunkyo Health Study. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulugerger Avci, G.; Bektan Kanat, B.; Can, G.; Suzan, V.; Unal, D.; Degirmenci, P.; Avci, S.; Yavuzer, H.; Erdincler, D.S.; Doventas, A. The impact of sarcopenia and obesity on mortality of older adults: Five years results. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 2209–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancello, R.; Brenna, E.; Soranna, D.; Zambon, A.; Villa, V.; Castelnuovo, G.; Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Capodaglio, P.; Brunani, A. Sarcopenia Prevalence Among Hospitalized Patients with Severe Obesity: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schluessel, S.; Mueller, K.; Drey, M. Comment on Cancello et al. Sarcopenia Prevalence Among Hospitalized Patients with Severe Obesity: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2880. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6685. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226685

Schluessel S, Mueller K, Drey M. Comment on Cancello et al. Sarcopenia Prevalence Among Hospitalized Patients with Severe Obesity: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2880. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(22):6685. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226685

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchluessel, Sabine, Katharina Mueller, and Michael Drey. 2024. "Comment on Cancello et al. Sarcopenia Prevalence Among Hospitalized Patients with Severe Obesity: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2880" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 22: 6685. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226685

APA StyleSchluessel, S., Mueller, K., & Drey, M. (2024). Comment on Cancello et al. Sarcopenia Prevalence Among Hospitalized Patients with Severe Obesity: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2880. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(22), 6685. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226685