The Relationship between Erectile Dysfunction, Self-Esteem, and Depression in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Demographics

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics

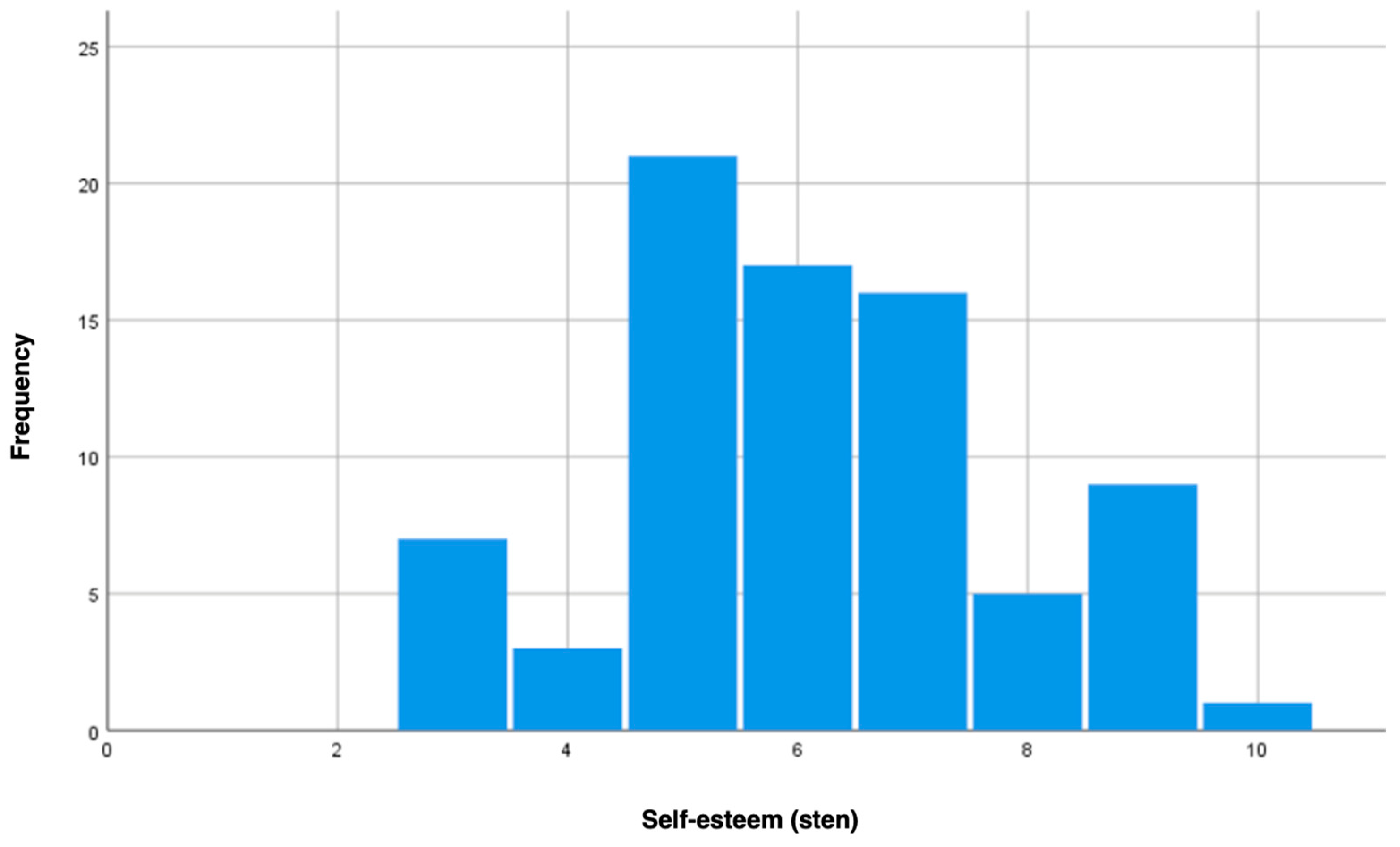

3.2. Self-Esteem in Post-MI Patients

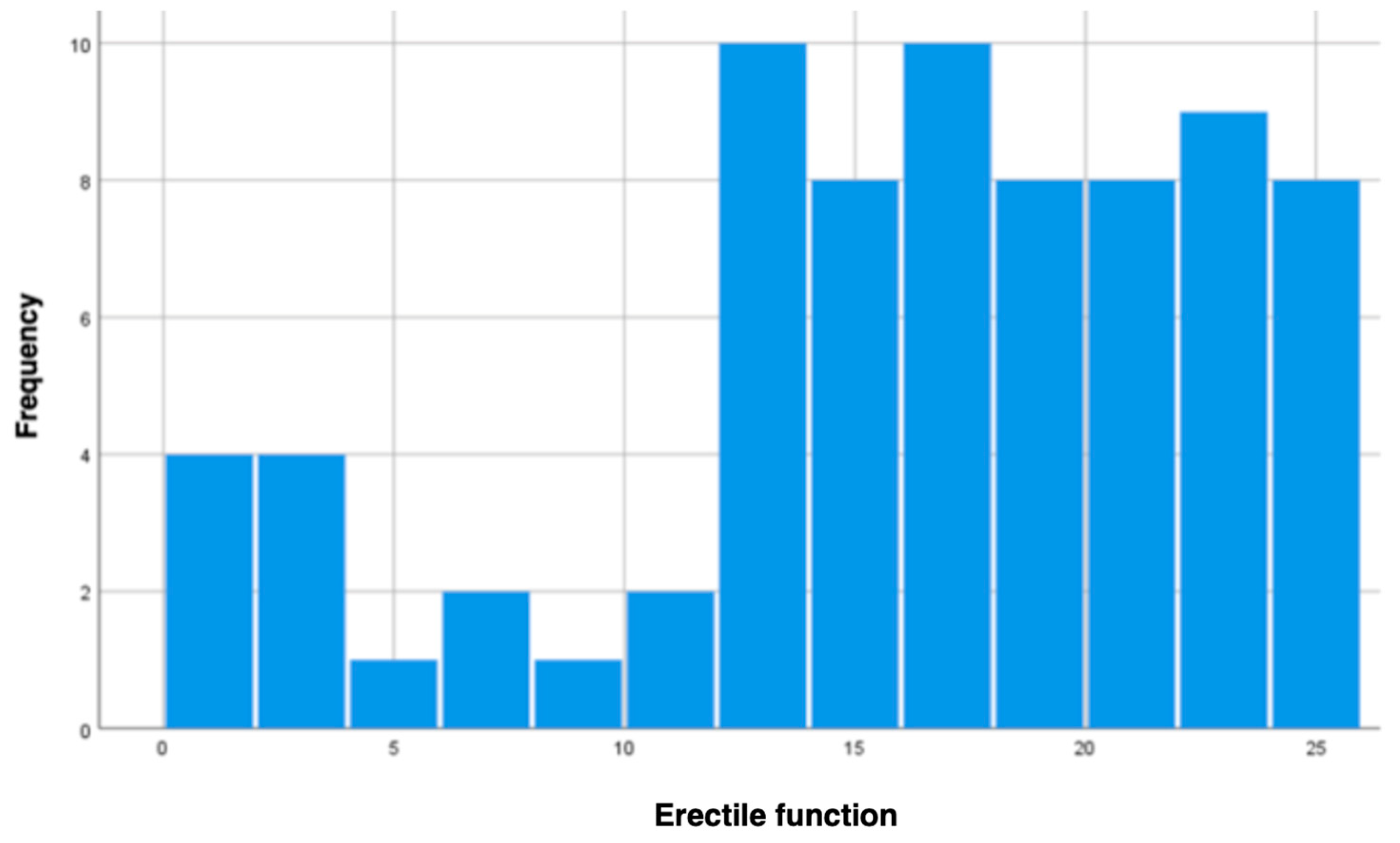

3.3. Erectile Function in Post-MI Patients

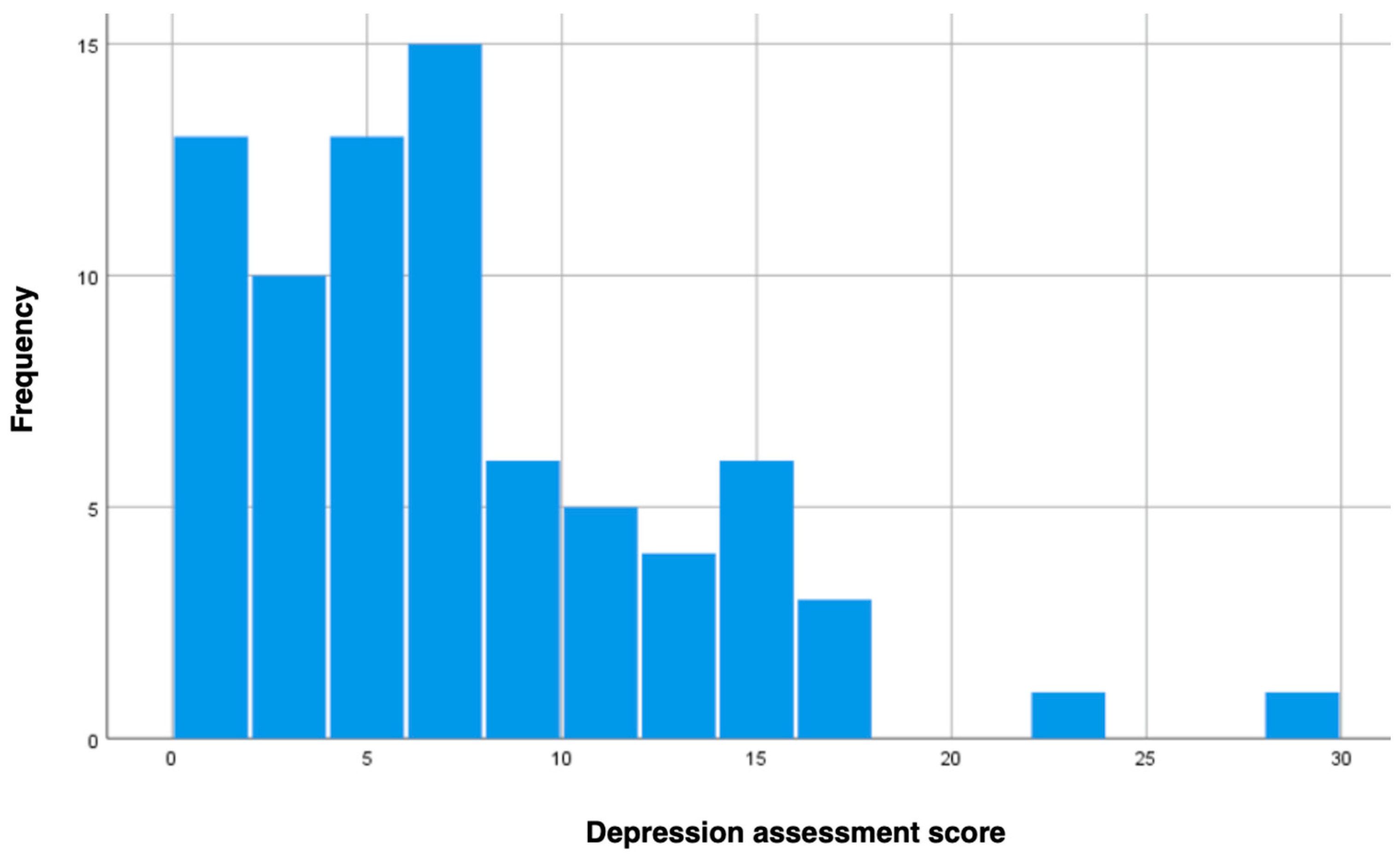

3.4. Depression Levels in Post-MI Patients

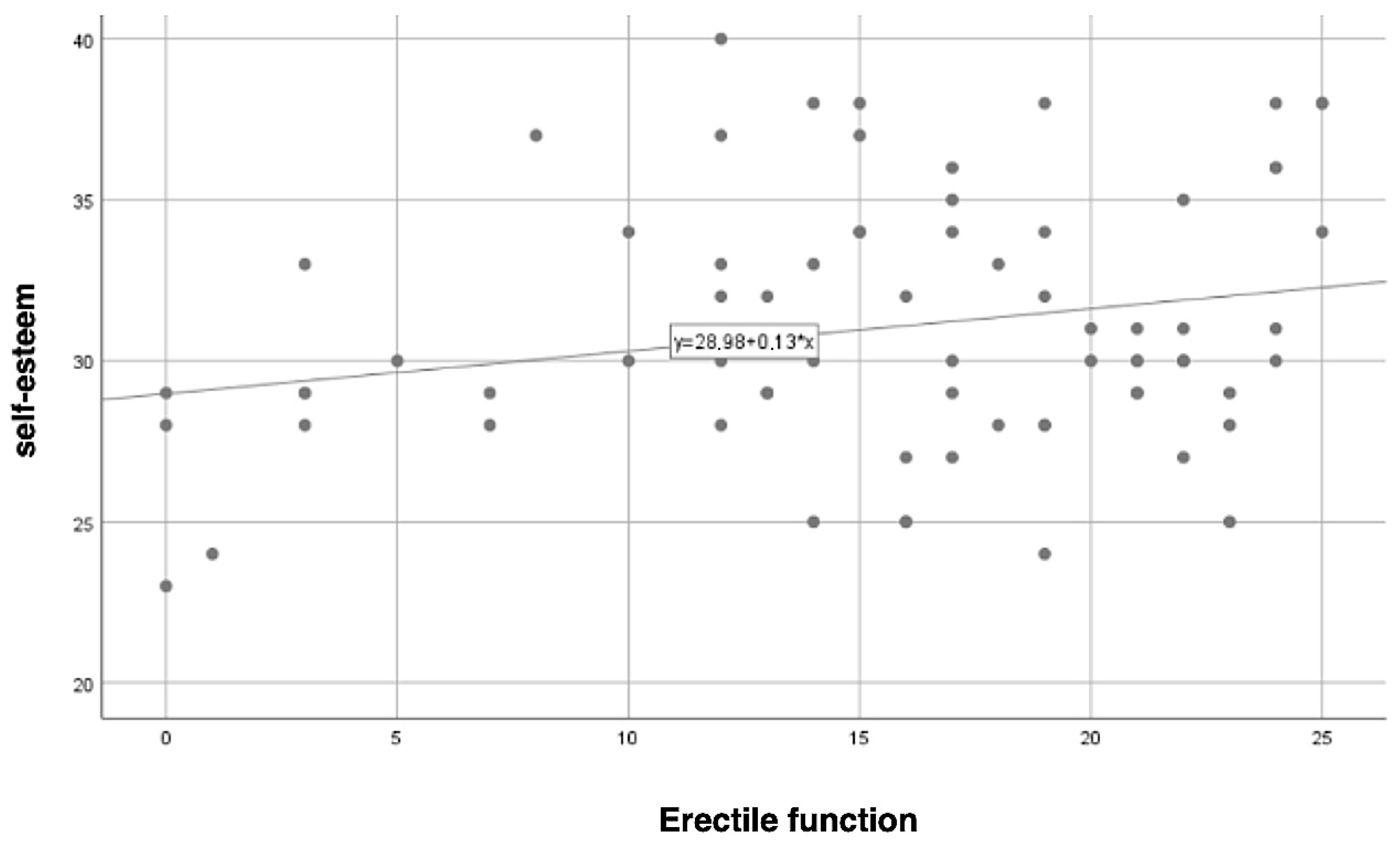

3.5. Correlation between Self-Esteem and Erectile Functioning

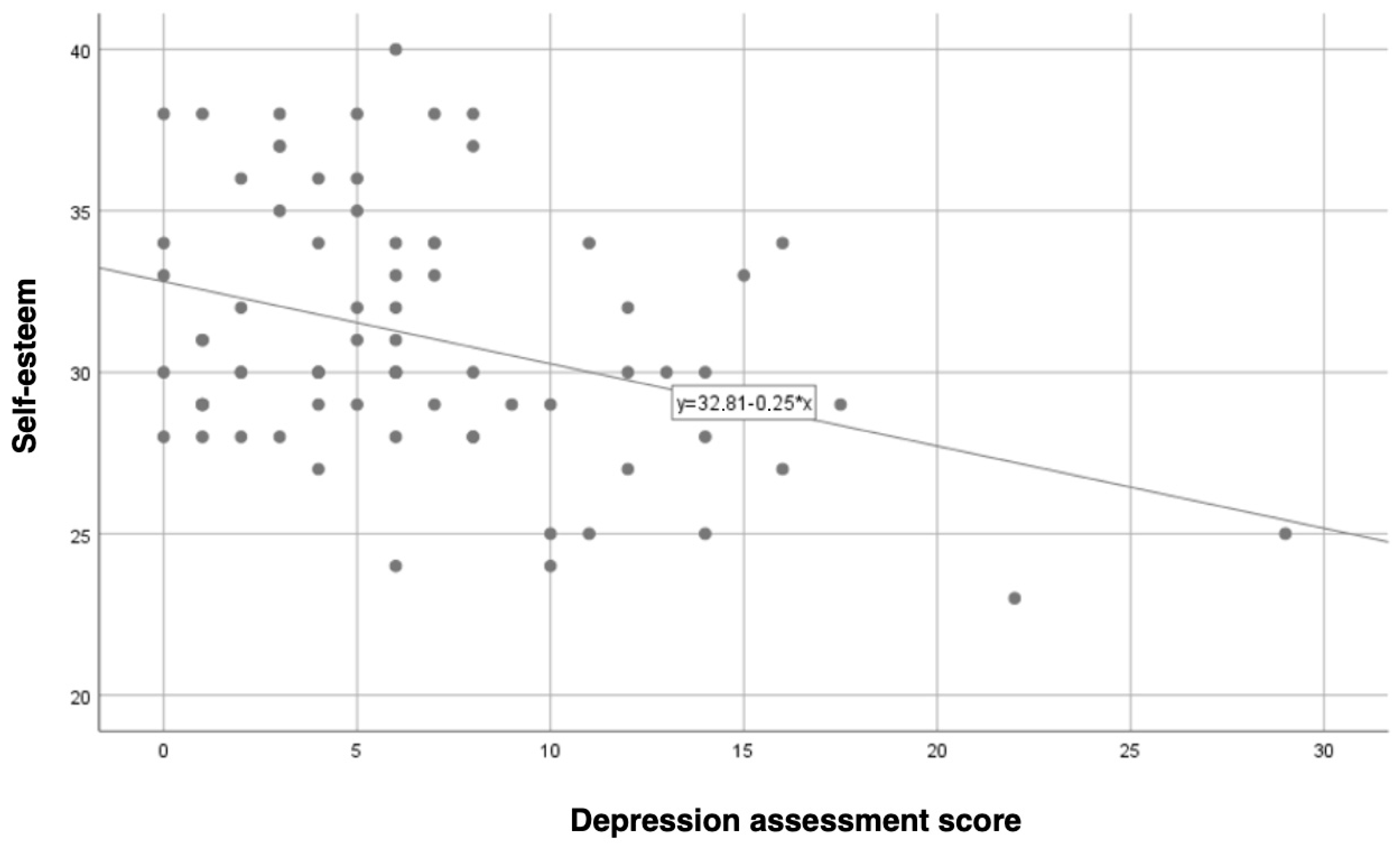

3.6. Correlation between Self-Esteem and Depression Levels

3.7. Other Demographic Variables

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salari, N.; Morddarvanjoghi, F.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaleghi, A.A.; Hezarkhani, L.A.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. The global prevalence of myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, Y.; Weston, S.A.; Jiang, R.; Roger, V.L. The changing epidemiology of myocardial infarction in olmsted county, minnesota, 1995–2012. Am. J. Med. 2014, 128, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Y.; Cao, H.; Ren, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; et al. Three therapeutic tendencies for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction and possible role of Chinese traditional patent medicine: Viewpoint of evidence-based medicine. J. Evid.-Based Med. 2009, 2, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Mei, S.; Gao, T.; Liang, L.; Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Guo, X.; Meng, C.; Lv, J.; Yuan, T.; et al. Self-esteem as a mediator between life satisfaction and depression among cardiovascular disease patients. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 31, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.R.; Rudnick, S.B.; Minami, H.R.; Chen, A.M.; Zemela, M.S.; Wittgen, C.M.; Williams, M.S.; Smeds, M.R. Depression screening in patients with vascular disease. Vascular 2022, 31, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Mansoor, D.; Langut, H.; Lorber, A. Quality of Life, Depressed Mood, and Self-Esteem in Adolescents With Heart Disease. Psychosom. Med. 2007, 69, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-H. Mental stress–induced myocardial ischemia and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA 2022, 327, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshfield, E.L.; Pennells, L.; Schwartz, J.E.; Willeit, P.; Kaptoge, S.; Bell, S.; Shaffer, J.A.; Bolton, T.; Spackman, S.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; et al. Association between depressive symptoms and incident cardiovascular diseases. JAMA 2020, 324, 2396–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, V.; Almuwaqqat, Z.; Kim, J.H.; Hammadah, M.; Shah, A.J.; Ko, Y.-A.; Elon, L.; Sullivan, S.; Shah, A.; Alkhoder, A.; et al. Association of mental stress–induced myocardial ischemia with cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA 2021, 326, 1818–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwonkowska, I.; Lachowicz-Tabaczek, K.; Łaguna, M. Skala samooceny SES Morrisa Rosenberga–polska adaptacja metody. Psychol. Społeczna 2007, 2, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, R.; Cappelleri, J.; Smith, M.D.; Lipsky, J.; Peña, B. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 1999, 11, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Shi, L.; Luo, M. Prevalence of depression in myocardial infarction: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e14596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytaç; McKinlay, J.B.; Krane, R.J. The likely worldwide increase in erectile dysfunction between 1995 and 2025 and some possible policy consequences. BJU Int. 1999, 84, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montorsi, P.; Montorsi, F.; Schulman, C.C. Is erectile dysfunction the “tip of the iceberg” of a systemic vascular disorder? Eur. Urol. 2003, 44, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Total Cardiovascular Risk; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hooshang, H.; Farahani, A.V.; Rezaeizadeh, H.; Forouzannia, S.K.; Alaeddini, F.; Ashraf, H.; Karimi, M. Efficacy of date palm pollen in the male sexual dysfunction after coronary artery bypass graft: A randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 5032681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tor-Anyiin, I.; Omokhua, O.E.; Swende, L.T. Association between erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular risk factors in a nigeria tertiary hospital. Rwanda Med. J. 2024, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Z.; Maguire, T.A.; Zou, K.H.; Lee, L.J.; Donde, S.S.; Taylor, D.G. Prevalence, comorbidities, and risk factors of erectile dysfunction: Results from a prospective real-world study in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2022, 5229702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Osta, A.; Kerr, G.; Alaa, A.; El Asmar, M.L.; Karki, M.; Webber, I.; Sasco, E.R.; Blume, G.; Beecken, W.-D.; Mummery, D. Investigating self-reported efficacy of lifestyle medicine approaches to tackle erectile dysfunction: A cross-sectional esurvey based study. BMC Urol. 2023, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A. Erectile dysfunction treatment improves self-esteem and quality of life in men with cardiovascular disease. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteynshlyuger, A.; Kaufman, M. Comparative effectiveness of different treatments for erectile dysfunction: Implications for improving self-esteem in post-MI patients. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2021, 33, 712–718. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, I. The mutually reinforcing triad of depressive symptoms, cardiovascular disease, and erectile dysfunction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000, 86, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadio, P.; Zarà, M.; Sandrini, L.; Ieraci, A.; Barbieri, S.S. Depression and Cardiovascular Disease: The Viewpoint of Platelets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Rastrelli, G.; Isidori, A.; Pivonello, R.; Bettocchi, C.; Reisman, Y.; Sforza, A.; Maggi, M. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular risk: A review of current findings. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2020, 18, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziapour, A.; Kazeminia, M.; Rouzbahani, M.; Bakhshi, S.; Montazeri, N.; Yıldırım, M.; Tadbiri, H.; Moradi, F.; Janjani, P. Global prevalence of sexual dysfunction in cardiovascular patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, J.-Y.; Chen, Z.-C.; Chang, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-W.; Ho, C.-H.; Chang, W.-T. Risks of age and sex on clinical outcomes post myocardial infarction. IJC Hear. Vasc. 2019, 23, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | ||

| Village | 13 | 16.3% |

| Town < 50,000 inhabitants | 11 | 13.8% |

| Town 50,000–150,000 inhabitants | 3 | 3.8% |

| City 150,000–500,000 inhabitants | 48 | 60% |

| No data | 5 | 6.3% |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 1 | 1.3% |

| Secondary | 23 | 28.7% |

| Technical/vocational | 32 | 40% |

| Higher education | 23 | 28.7% |

| No data | 1 | 1.3% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 57 | 71.3% |

| Unmarried partnership | 9 | 11.3% |

| Widowed | 2 | 2.5% |

| Single | 11 | 13.8% |

| No data | 1 | 1.3% |

| Occupational status | ||

| Retired | 23 | 28.7% |

| Employed | 51 | 63.7% |

| No data | 6 | 7.5% |

| Variable | M | Me | SD | Sk. | Kurt. | Min | Max | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.06 | 57.50 | 10.12 | −0.19 | −0.80 | 35 | 77 | 0.98 | 0.202 |

| Self-Esteem (SES) | 31.05 | 30 | 3.87 | 0.31 | −0.45 | 23 | 40 | 0.96 | 0.019 |

| Erectile Function (IIEF-5) | 15.71 | 17 | 6.79 | −0.78 | −0.12 | 0 | 25 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

| Depression Level (BDI-II) | 6.80 | 6 | 5.54 | 1.34 | 2.54 | 0 | 29 | 0.90 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wróblewski, O.; Skwirczyńska, E.; Michalczyk, K.; Zaeir, S.; Zair, L.; Kraszewska, K.; Kiryk, J.; Bobik, A.; Mikołajczyk-Kocięcka, A.; Chudecka-Głaz, A. The Relationship between Erectile Dysfunction, Self-Esteem, and Depression in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13206134

Wróblewski O, Skwirczyńska E, Michalczyk K, Zaeir S, Zair L, Kraszewska K, Kiryk J, Bobik A, Mikołajczyk-Kocięcka A, Chudecka-Głaz A. The Relationship between Erectile Dysfunction, Self-Esteem, and Depression in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(20):6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13206134

Chicago/Turabian StyleWróblewski, Oskar, Edyta Skwirczyńska, Kaja Michalczyk, Samir Zaeir, Labib Zair, Klara Kraszewska, Julia Kiryk, Alicja Bobik, Anna Mikołajczyk-Kocięcka, and Anita Chudecka-Głaz. 2024. "The Relationship between Erectile Dysfunction, Self-Esteem, and Depression in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 20: 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13206134

APA StyleWróblewski, O., Skwirczyńska, E., Michalczyk, K., Zaeir, S., Zair, L., Kraszewska, K., Kiryk, J., Bobik, A., Mikołajczyk-Kocięcka, A., & Chudecka-Głaz, A. (2024). The Relationship between Erectile Dysfunction, Self-Esteem, and Depression in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(20), 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13206134