Prevalence of Unwanted Loneliness and Associated Factors in People over 65 Years of Age in a Health Area of the Region of Murcia, Spain: HELPeN Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample and Setting

2.3. Variables and Measurement Instruments

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Considerations

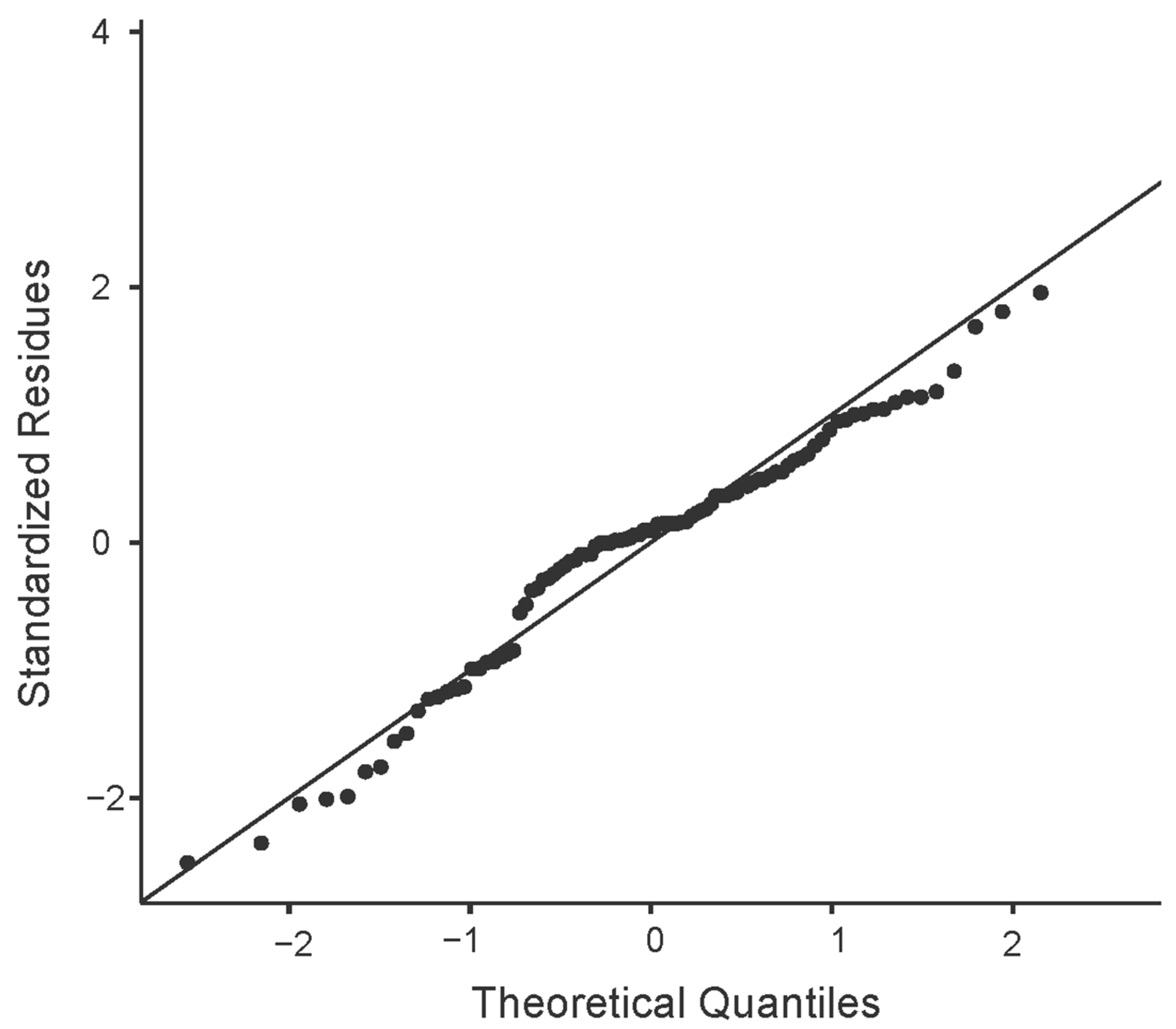

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Participants

3.2. Results from the Measurement Tools

3.3. Correlation and Regression Models of the Study Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications and Future Directions

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadisitca (INE). Proyecciones de Población. Available online: https://ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/es/PROP20242074.htm (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Beard, J.R.; Bloom, D.E. Towards a Comprehensive Public Health Response to Population Ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg-Weger, M.; Morley, J.E. Loneliness in Old Age: An Unaddressed Health Problem. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzman, R.; Beard, J.R.; Boerma, T.; Chatterji, S. Health in an Ageing World—What Do We Know? Lancet 2015, 385, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguna, L.; Fiszman, S.; Puerta, P.; Chaya, C.; Tárrega, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Food Priorities. Results from a Preliminary Study Using Social Media and an Online Survey with Spanish Consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzafa-Martinez, M.; García-González, J.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Leal-Costa, C.; Hernández-Méndez, S.; Hernández-López, M.J.; Albarracín-Olmedo, J.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Complex Multimorbid Elderly: Follow-up of a Community-Based Cohort. SAMAC3 Study. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2023, 55, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Norman, G.J.; Berntson, G.G. Social Isolation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1231, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Edelman, L.S.; Tracy, E.L.; Demiris, G.; Sward, K.A.; Donaldson, G.W. Loneliness as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Isolation on Cognitive Functioning of Chinese Older Adults. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplau, L.A.; Perlman, D. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy. Contemp. Sociol. 1984, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissinotto, C.M.; Stijacic Cenzer, I.; Covinsky, K.E. Loneliness in Older Persons: A Predictor of Functional Decline and Death. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, T.K.M.; Roth, D.L.; Szanton, S.L.; Wolff, J.L.; Boyd, C.M.; Thorpe, R.J. The Epidemiology of Social Isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J. Gerontol.-Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, K.; Kunonga, T.P.; Stow, D.; Barker, R.; Craig, D.; Hanratty, B. Prevalence of Loneliness amongst Older People in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vozikaki, M.; Linardakis, M.; Philalithis, A. Preventive Health Services Utilization in Relation to Social Isolation in Older Adults. J. Public Health 2017, 25, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso González, A.; Qués, A.M.; Salgado Babarro, L.; Vázquez Domínguez, C.; Ramos Cid, Á.; Del, M.; López Pérez, C. Soledad y Aislamiento Social en Personas Mayores de Una Población Rural de Galicia. Gerokomos 2023, 34, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gayol Fernández, M.; Arguiano, J.S.; Conde Díez, Y. Aislamiento Social y Dependencia en la Población Anciana de Una Población Rural. RqR Enfermería Comunitaria 2020, 8, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gené-Badia, J.; Comice, P.; Belchín, A.; Erdozain, M.Á.; Cáliz, L.; Torres, S.; Rodríguez, R. Profiles of Loneliness and Social Isolation in Urban Population. Aten. Primaria 2020, 52, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beridze, G.; Ayala, A.; Ribeiro, O.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Forjaz, M.J.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A. Are Loneliness and Social Isolation Associated with Quality of Life in Older Adults? Insights from Northern and Southern Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garcia, M.; Sansano-Sansano, E.; Castillo-Hornero, A.; Femenia, R.; Roomp, K.; Oliver, N. Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: A Population Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, L.C.; Steptoe, A. Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Health Behaviors at Older Ages: Longitudinal Cohort Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L.; Pearce, E.; Ajnakina, O.; Johnson, S.; Lewis, G.; Mann, F.; Pitman, A.; Solmi, F.; Sommerlad, A.; Steptoe, A.; et al. The Association between Loneliness and Depressive Symptoms among Adults Aged 50 Years and Older: A 12-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausín, B.; Muñoz, M.; Castellanos, M.A. Loneliness, Sociodemographic and Mental Health Variables in Spanish Adults over 65 Years Old. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, N.H. Concepts of Researching the Loneliness of Elderly. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 1, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, K.L.; Turan, B.; McCormick, L.; Durojaiye, M.; Nyblade, L.; Kempf, M.C.; Lichtenstein, B.; Turan, J.M. HIV-Related Stigma Among Healthcare Providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tragantzopoulou, P.; Giannouli, V. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Old Age: Exploring Their Role in Mental and Physical Health. Psychiatrike 2021, 32, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julsing, J.E.; Kromhout, D.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Giltay, E.J. Loneliness and All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Noncardiovascular Mortality in Older Men: The Zutphen Elderly Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 24, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo-Rodríguez, L.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; Rojas-Russell, M.E. Elder Abuse and Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Loneliness in Older Adults. Arch. Med. Res. 2024, 55, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaka, J.; Thompson, S.; Palacios, R. The Relation of Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Social Support to Disease Outcomes among the Elderly. J. Aging Health 2006, 18, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Peralta, L.P.; Sánchez-Moreno, E.; Rodríguez, V.R.; Martín, M.G. La Investigación Sobre Soledad. Rev. Esp. Saúde Pública 2023, 97, e202301006. [Google Scholar]

- Surkalim, D.L.; Luo, M.; Eres, R.; Gebel, K.; Van Buskirk, J.; Bauman, A.; Ding, D. The Prevalence of Loneliness across 113 Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2022, 376, e067068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness, Isolation and the Health of Older Adults: Do We Need a New Research Agenda? J. R. Soc. Med. Suppl. 2012, 105, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Estatal de la Soledad No Deseada Barómetro de la Soledad No Deseada en España. Available online: https://www.soledades.es/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- Velarde-Mayol, C.; Fragua-Gil, S.; García-de-Cecilia, J.M. Validación de La Escala de Soledad de UCLA y Perfil Social en la Población Anciana Que Vive Sola. Semergen 2016, 42, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Frades-Payo, B.; Forjaz, M.J.; Martínez-Martín, P.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Pérez, F. Propiedades Psicométricas del Cuestionario de Apoyo Social Funcional y de la Escala de Soledad en Adultos Mayores No Institucionalizados en España. Gac. Sanit. 2012, 26, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega Orcos, R.; Salinero Fort, M.A.; Kazemzadeh Khajoui, A.; Vidal Aparicio, S.; De Dios Del Valle, R. Validación de la Versión Española de 5 y 15 Ítems de la Escala de Depresión Geriátrica en Personas Mayores en Atención Primaria. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2007, 207, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez De La Iglesia, J.; Herrero, R.D.; Vilches, M.C.O.; Taberné, C.A.; Colomer, C.A.; Luque, R.L. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of Pfeiffer’s Test (Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire [SPMSQ]) to Screen Cognitive Impairment in General Population Aged 65 or Older. Med. Clin. 2001, 117, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royuela Rico, A.; Macías Fernández, J.A. Propiedades Clinimétricas de la Versión Castellana del Cuestionario de Pittsburgh. Vigilia-Sueño 1997, 9, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaola-Sagardui, I. Validation of the Barthel Index in the Spanish Population. Enferm. Clin. 2018, 28, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-López, M.J.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Leal-Costa, C.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Díaz-García, I.; López-Pérez, M.V.; Hernández-Méndez, S.; García-González, J. Effects of a Clinical Simulation-Based Training Program for Nursing Students to Address Social Isolation and Loneliness in the Elderly: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samper, M.B. Reglamento (Ue) 2016/679 del Parlamento Europeo Y del Consejo de 27 de Abril de 2016, Relativo a la Protección de las Personas Físicas en lo Que Respecta al Tratamiento de Datos Personales Y a la Libre Circulación de Estos Datos Y Por El Que Se Deroga La. Prot. Pers. 2020, 2014, 17–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassarino, M.; Bantry-White, E.; Setti, A. Neighbourhood Environment and Cognitive Vulnerability—A Survey Investigation of Variations across the Lifespan and Urbanity Levels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitte, T.; Mallow, J.; Barnes, E.; Petrone, A.; Barr, T.; Theeke, L. A Systematic Review of Loneliness and Common Chronic Physical Conditions in Adults. Open Psychol. J. 2015, 8, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feeley, T.H. Social Support, Social Strain, Loneliness, and Well-Being among Older Adults: An Analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2014, 31, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.C. Loneliness: A Disease? Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Rao, W.; Li, M.; Caron, G.; D’Arcy, C.; Meng, X. Prevalence of Loneliness and Social Isolation among Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 35, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotwal, A.A.; Cenzer, I.S.; Waite, L.J.; Covinsky, K.E.; Perissinotto, C.M.; Boscardin, W.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Dale, W.; Smith, A.K. The Epidemiology of Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older Adults during the Last Years of Life. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 3081–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanova, S.Y.; Giannouli, V.; Gergov, T.K. Sentimentality and Nostalgia in Elderly People in Bulgaria and Greece—Cross-Validity of the Questionnaire Snep and Cross-Cultural Comparison. Eur. J. Psychol. 2017, 13, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Cho, T.C.; Westrick, A.C.; Chen, C.; Langa, K.M.; Kobayashi, L.C. Association of Cumulative Loneliness with All-Cause Mortality among Middle-Aged and Older Adults in the United States, 1996 to 2019. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2306819120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, T.J.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Van Tilburg, T.G.; Stek, M.L.; Jonker, C.; Schoevers, R.A. Feelings of Loneliness, but Not Social Isolation, Predict Dementia Onset: Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2014, 85, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Lara, E.; Rubio-Valera, M.; Olaya, B.; Moneta, M.V.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M. Loneliness and Depression in the Elderly: The Role of Social Network. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.R.; Westbury, L.; Cooper, C. Social Isolation and Loneliness as Risk Factors for the Progression of Frailty: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Health in Old Age: A Scoping Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, L.; Agahi, N.; Lennartsson, C. Lonelier than Ever? Loneliness of Older People over Two Decades. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 75, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczynski, A.M.; Piccirillo, M.; Dora, J.; Kuehn, K.S.; Halvorson, M.A.; King, K.M.; Kanter, J. Characterizing the Momentary Association between Loneliness, Depression, and Social Interactions: Insights from an Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 360, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, N.J.; Blazer, D. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categorical Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48 | 47.1 |

| Female | 54 | 52.9 |

| Nationality | ||

| Spain | 99 | 97 |

| Ecuador | 2 | 2 |

| Argentina | 1 | 1 |

| Level of education | ||

| None | 71 | 69.6 |

| Primary (EGB, primary, ESO) | 22 | 21.5 |

| Secondary (vocational, baccalaureate) | 2 | 2.0 |

| University | 7 | 6.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 11 | 10.8 |

| Married | 45 | 44.1 |

| Divorced | 3 | 2.9 |

| Separated | 6 | 5.9 |

| Widowed | 37 | 36.3 |

| Environment | ||

| Urban (equal to or more than 50,000 inhab.) | 15 | 14.7 |

| Semi-urban (10,000 a <50,000 inhab.) | 55 | 53.9 |

| Rural (<10,000 habt) | 32 | 31.4 |

| Number of cohabitants | ||

| 0 | 8 | 7.8 |

| 1 | 50 | 49.0 |

| 2 | 36 | 35.3 |

| 3 | 6 | 5.9 |

| 4 | 2 | 2.0 |

| Quantitative variables | M | SD |

| Age (years) | 75.76 | 6.36 |

| No. of children | 2.12 | 1.53 |

| Loneliness (UCLA) (range 10–40) | 34.41 | 6.18 |

| <20 Severe degree of loneliness (n %) | 2 | 2 |

| 20–30 Moderate loneliness (n %) | 30 | 29.4 |

| Social isolation (DUFSS) (range 11–55) | 41.70 | 8.55 |

| <32 Low perceived social support (n %) | 15 | 14.7 |

| ≥32 Low perceived social support (n %) | 87 | 85.3 |

| Depression (GDS) (range 0–15 points) | 2.40 | 2.08 |

| Cognitive deterioration (SPSMQ) | 0.81 | 1.28 |

| 0–2 Normal (n %) | 90 | 88.2 |

| 3–4 Slight cognitive deterioration (n %) | 11 | 10.8 |

| 5–7 Moderate cognitive deterioration (n %) | 1 | 1.0 |

| 8–10 Severe cognitive deterioration (n %) | 0 | 0 |

| Sleep quality (PSQI) (range 0–21) | 5.17 | 3.13 |

| Level of mobility, functionality, and physical state (Barthel) (range 0–100) | 96.78 | 7.54 |

| Age | DUK | BTH | GDS | PFE | PIT | UCLA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | ||||||

| DUK | 0.051 | 1 | |||||

| BTH | −0.513 ** | −0.002 | 1 | ||||

| GDS | −0.040 | −0.495 ** | −0.279 ** | 1 | |||

| PFE | 0.474 ** | −0.084 | −0.403 ** | 0.224 * | 1 | ||

| PIT | 0.071 | −0.317 ** | −0.232 * | 0.529 ** | 0.241 * | 1 | |

| UCLA | 0.040 | 0.692 ** | 0.160 | −0.534 ** | −0.271 ** | −0.395 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Loneliness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| Independent Variables | β | t | p-Value | R2 Adjust | β | t | p-Value |

| Social isolation (DUFSS) | 0.692 | 9.58 | <0.001 | 0.473 | 0.567 | 6.78 | <0.001 |

| Depression (GDS) | −0.534 | −6.12 | <0.001 | 0.277 | −0.221 | −2.58 | 0.012 |

| Cognitive deterioration (SPSMQ) | −0.271 | −2.79 | 0.006 | 0.064 | −0.148 | −1.98 | 0.050 |

| Sleep quality (PSQI) | −0.395 | −4.17 | <0.001 | 0.147 | |||

| Level of mobility, functionality, and physical state (Barthel) | 0.160 | 1.61 | 0.11 | 0.016 | |||

| Age (years) | 0.040 | 0.40 | 0.69 | −0.008 | |||

| R = 0.727; adjusted R2 = 0.513; F = 34.004; p < 0.001; Durbin–Watson’s D statistic = 2.04 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-López, M.J.; Hernández-Méndez, S.; Leal-Costa, C.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Díaz-García, I.; López-Pérez, M.V.; García-González, J.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M. Prevalence of Unwanted Loneliness and Associated Factors in People over 65 Years of Age in a Health Area of the Region of Murcia, Spain: HELPeN Project. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185604

Hernández-López MJ, Hernández-Méndez S, Leal-Costa C, Ramos-Morcillo AJ, Díaz-García I, López-Pérez MV, García-González J, Ruzafa-Martínez M. Prevalence of Unwanted Loneliness and Associated Factors in People over 65 Years of Age in a Health Area of the Region of Murcia, Spain: HELPeN Project. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(18):5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185604

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-López, María Jesús, Solanger Hernández-Méndez, César Leal-Costa, Antonio Jesús Ramos-Morcillo, Isidora Díaz-García, María Verónica López-Pérez, Jessica García-González, and María Ruzafa-Martínez. 2024. "Prevalence of Unwanted Loneliness and Associated Factors in People over 65 Years of Age in a Health Area of the Region of Murcia, Spain: HELPeN Project" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 18: 5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185604

APA StyleHernández-López, M. J., Hernández-Méndez, S., Leal-Costa, C., Ramos-Morcillo, A. J., Díaz-García, I., López-Pérez, M. V., García-González, J., & Ruzafa-Martínez, M. (2024). Prevalence of Unwanted Loneliness and Associated Factors in People over 65 Years of Age in a Health Area of the Region of Murcia, Spain: HELPeN Project. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(18), 5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185604