KidsTUMove—A Holistic Program for Children with Chronic Diseases, Increasing Physical Activity and Mental Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aims and Scopes

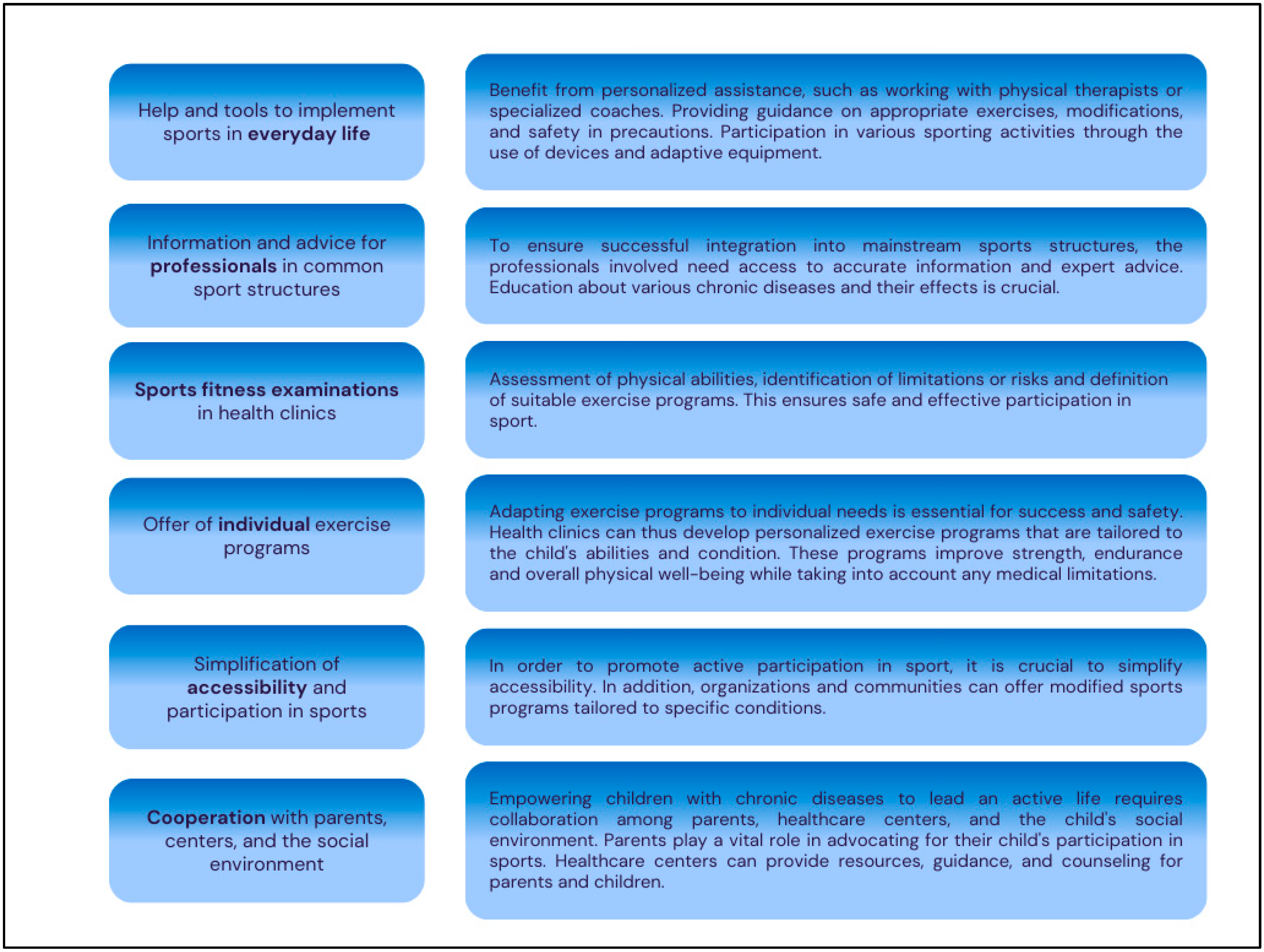

2.1. Encouragement in Children with Chronic Diseases through Specialized Sports Activities and Personal Support

2.2. Empowering Children Leading an Active Life

2.3. Enhancing Quality of Life for Children with Chronic Diseases: Comprehensive—Support for Overall Well-Being

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Program Design and Participant Recruitment

- All participants aged 4–18 with a chronic disease;

- Medical certification of fitness for physical activity;

- Parental/guardian consent for participation.

- Deterioration in general health;

- Injuries and acute illnesses (Infections, diseases, open wounds).

- Sports science professionals: Sports scientists lead the multidisciplinary team and investigate the effects of physical activity on children with chronic diseases. They develop the program’s sports education concept and organize, evaluate, and carry out the sports activities.

- Health science professionals: KidsTUMove recognizes the importance of collaboration with health science professionals within the healthcare system. They contribute their expertise in pediatric health, nutrition, and psychology, providing valuable insights and ensuring the program aligns with evidence-based practices. This collaboration ensures that KidsTUMove remains at the forefront of health education for children.

- Pediatricians: Pediatricians and sports physicians assess the physical fitness of the participants and provide medical care during the sporting activities.

- University students: KidsTUMove benefits from a large group of university students who have the opportunity to learn about the program’s concepts and principles. Through their involvement, they gain valuable experience and knowledge in promoting physical activity among children. These students act as ambassadors and can further disseminate the program’s concepts to the broader community.

- Exercise professionals and coaches: As KidsTUMove expands its reach, it aims to establish partnerships with schools and educational institutions to create a sustainable framework. The framework involves training and supporting coaches in delivering the program’s activities. Coaches are trained in child development, physical education, and health promotion. They serve as role models and mentors for the children, guiding them toward a more active lifestyle.

3.2. Program Evaluation and Assessments

4. Results

4.1. Program Overview

4.2. Move It—Integrative Sports Group

4.3. Summer and Winter Camps

4.4. Weekend Events

4.5. Climbing Group

4.6. KidsTUMove Goes Online!

4.7. Tailoring KidsTUMove Activities for Pediatric Chronic Diseases

4.8. Funding and Resource Allocation

- Diverse Funding Sources: Securing support from government grants, private donations, and partnerships with healthcare organizations was crucial to maintaining a consistent resource flow for program maintenance and expansion.

- Efficient Resource Use: Prioritizing the development of tailored materials, training for staff, and maintaining technological platforms was essential. Allocating resources for regular program evaluation and feedback collection ensured continuous improvement.

- Community Partnerships: Collaborations with local healthcare providers, schools, and community organizations enhanced resource sharing and broadened the program’s reach. These partnerships facilitated referrals and increased program visibility.

- Scalability Planning: A modular approach allowed for replicating successful program elements in new locations. Pilot programs helped refine strategies before broader implementation, ensuring adaptability to different community needs and resources.

5. Partners and Collaborations

6. Discussion

6.1. Positive Impacts on Children

6.2. Benefits to Families

6.3. Comparative Analysis with Other Offers in Europe

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perrin, J.M.; Bloom, S.R.; Gortmaker, S.L. The Increase of Childhood Chronic Conditions in the United States. JAMA 2007, 297, 2755–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Dunn, M.J.; Rodriguez, E.M. Coping with Chronic Illness in Childhood and Adolescence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 455–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cleave, J.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Perrin, J.M. Dynamics of Obesity and Chronic Health Conditions among Children and Youth. JAMA 2010, 303, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, L.; Vogelgesang, F.; Thamm, R.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Damerow, S.; Scklack, R.; Junker, S.; Mauz, E. Individual trajectories of asthma, obesity and ADHD during the transition from childhood and adolescence to young adulthood. J. Health Monit. 2021, 6, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Durstine, J.L. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Chronic Diseases: A Brief Review. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2019, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.B.; Fernández, C.S.; de Oliveira, M.B.; Lagos, C.M.; Martínez, M.T.B.; Hernández, C.L.; González, I.d.C. Chronic Diseases in the Paediatric Population: Comorbidities and Use of Primary Care Services. An. Pediatría 2020, 93, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yomoda, K.; Kurita, S. Influence of Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity in Children: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2021, 19, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzan-Bluma, I.; Lipowska, M. Physical Activity and Cognitive Functioning of Children: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, S.L.C.; A Paw, M.J.M.C.; Altenburg, T.M. Physical Activity and Prospective Associations with Indicators of Health and Development in Children Aged <5 Years: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, S.; Sanders, S.W. Physical Education in Early Childhood. Elem. Sch. J. 2008, 108, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantomaa, M.T.; Tammelin, T.H.; Ebeling, H.E.; Taanila, A.M. Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Relation to Physical Activity in Youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammelin, T.; Näyhä, S.; Laitinen, J.; Rintamäki, H.; Järvelin, M.-R. Physical Activity and Social Status in Adolescence as Predictors of Physical Inactivity in Adulthood. Prev. Med. 2003, 37, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wind, W.M.; Schwend, R.M.; Larson, J. Sports for the Physically Challenged Child. JAAOS-J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2004, 12, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1· 6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, C.; Beneke, R.; Bloch, W.; Bucksch, J.; Dordel, S.; Eiser, S.; Ferrari, N.; Koch, B.; Krug, S.; Lawrenz, W.; et al. Vorschläge zur Förderung der körperlichen Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde 2013, 161, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, C.; Sigrid, D.; Benjamin, K.; Hans-Georg, P. Bewegungsmangel und Übergewicht Bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 2006, 57, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman, J.R.; Thompson, P.D.; Lantos, J.; Berul, C.I.; Botkin, J.; Cohen, J.T.; Cook, N.R.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.; Frick, K.D. Screening for Sudden Cardiac Death in the Young: Report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group. Circulation 2011, 123, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavey, R.-E.W.; Daniels, S.R.; Flynn, J.T. Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Cardiol. Clin. 2010, 28, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic Review of the Health Benefits of Physical Activity and Fitness in School-Aged Children and Youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 9789241550536. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Pitti, J.; Casajús-Mallén, J.A.; Leis-Trabazo, R.; Lucía, A.; de Lara, D.L.; Moreno-Aznar, L.A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Exercise as Medicine in Chronic Diseases during Childhood and Adolescence. An. Pediatría 2020, 92, 173.e1–173.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.L.; Banks, L.; Schneiderman, J.E.; Caterini, J.E.; Stephens, S.; White, G.; Dogra, S.; Wells, G.D. Physical Activity for Children with Chronic Disease: A Narrative Review and Practical Applications. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siaplaouras, J.; Albrecht, C.; Apitz, C. Sport Mit Angeborenem Herzfehler–Wo Stehen Wir 2017? Swiss Sports Exerc. Med. 2017, 65, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, P.H.; King, N.A.; Armstrong, T.P. The Contribution of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviours to the Growth and Development of Children and Adolescents: Implications for Overweight and Obesity. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 533–545. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, J.; Houghton, K.; Luke, A.; Canadian Paediatric Society, & Healthy Active Living; Sports Medicine Committee. Physical Activity Recommendations for Children with Specific Chronic Health Conditions: Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, Hemophilia, Asthma and Cystic Fibrosis. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 15, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoff, M.; Held, K.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B. Cardiac Rehabilitation in Germany. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2007, 14, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Alcaraz, J.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Faucette, F.N. Effects of a Physical Education Program on Children’s Manipulative Skills. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1998, 17, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, S.M.; Baryza, M.J.; Webster, H.C. Pediatric Rehabilitation and Recovery of Children with Traumatic Injuries. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 1992, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, A.; Tietjens, M. Bewegung, Spiel und Sport in der Rehabilitation und Reintegration krebskranker Kinder und Jugendlicher: Ein Situationsbericht. BG Bewegungstherapie Gesundheitssport 2010, 26, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M.; King-Shier, K.M.; Thompson, D.R.; Spaling, M.A.; Duncan, A.S.; Stone, J.A.; Jaglal, S.B.; Angus, J.E. A Qualitative Systematic Review of Influences on Attendance at Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs after Referral. Am. Heart J. 2012, 164, 835–845.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voll, R. Aspects of the Quality of Life of Chronically Ill and Handicapped Children and Adolescents in Outpatient and Inpatient Rehabilitation. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2001, 24, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrenz, W. Sport und Körperliche Aktivität Für Kinder Mit Angeborenen Herzfehlern. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 2007, 58, 334–337. [Google Scholar]

- Holger, F. Kindersportmedizin. In Kompendium der Sportmedizin: Physiologie, Innere Medizin und Pädiatrie; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2017; pp. 419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanie, N.S. Kidstumove: Hintergründe und Ausblicke Für Gesundes Bewegungsverhalten Bei Kindern und Jugendlichen Mit Angeborenem Herzfehler; Technische Universität München: München, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stöcker, N.; Oberhoffer, R.; Gaser, D.; Sitzberger, C. Kidstumove Wintercamp: A Pilot Project for Children with Congenital Heart Diseases. Cardiol. Young 2019, 29 (Suppl. 1), S189. [Google Scholar]

- Wippermann, F.; Oberhoffer, R.; Hager, A. Sport Bei Angeborenen Herzerkrankungen. Klin. Pädiatrie 2017, 229, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.R. The Effects of Exercise on Self-Perceptions and Self-Esteem. In Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 100–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, L.; Lähteenmäki, P.M.; Pukkila, H.; Arola, M.; Axelin, A.; Salanterä, S.; Järvelä, L.S. Motor Performance in Children Diagnosed with Cancer: A Longitudinal Observational Study. Children 2020, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagas, D.D.V.; Carvalho, J.F.; Batista, L.A. Do Girls with Excess Adiposity Perform Poorer Motor Skills than Leaner Peers? Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2016, 9, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Greier, K. Einfluss von Übergewicht und Adipositas Auf Die Motorische Leistungsfähigkeit Bei Grundschulkindern. Padiatrie Padol. 2014, 49, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuveer, G.; Hartz, J.; Lubans, D.R.; Takken, T.; Wiltz, J.L.; Mietus-Snyder, M.; Perak, A.M.; Baker-Smith, C.; Pietris, N.; Edwards, N.M. Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Youth: An Important Marker of Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, e101–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amedro, P.; Picot, M.; Moniotte, S.; Dorka, R.; Bertet, H.; Guillaumont, S.; Barrea, C.; Vincenti, M.; De La Villeon, G.; Bredy, C.; et al. Correlation between Cardio-Pulmonary Exercise Test Variables and Health-Related Quality of Life among Children with Congenital Heart Diseases. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 203, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, T.; Mertens, L. Physical Performance and Physical Activity in Grown-Up Congenital Heart Disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2005, 12, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, L.; Hillis, W.S. Exercise Prescription in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: A Long Way to Go. Heart 2000, 83, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amedro, P.; Dorka, R.; Moniotte, S.; Guillaumont, S.; Fraisse, A.; Kreitmann, B.; Borm, B.; Bertet, H.; Barrea, C.; Ovaert, C.; et al. Quality of Life of Children with Congenital Heart Diseases: A Multicenter Controlled Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2015, 36, 1588–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moons, P.; Van Deyk, K.; De Geest, S.; Gewillig, M.; Budts, W. Is the Severity of Congenital Heart Disease Associated with the Quality of Life and Perceived Health of Adult Patients? Heart 2005, 91, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bös, K.; Schlenker, L. Deutscher Motorik-Test 6–18 (Dmt 6–18). In Bildung im Sport: Beiträge zu Einer Zeitgemäßen Bildungsdebatte; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Bullinger, M. Assessing Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronically Ill Children with the German KINDL: First Psychometric and Content Analytical Results. Qual. Life Res. 1998, 7, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landgraf, J.M. Measuring Pediatric Outcomes in Applied Clinical Settings: An Update About the Child Health Questionnaire (Chq). Qual. Life Newsl. 1999, 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hänggi, J.M.; Phillips, L.R.; Rowlands, A.V. Validation of the GT3X ActiGraph in Children and Comparison with the GT1M ActiGraph. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European Kidscreen Approach to Measure Quality of Life and Well-Being in Children: Development, Current Application, and Future Advances. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Ellert, U.; Erhart, M. Health-Related Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents in Germany. Norm Data from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (Kiggs) Eine Normstichprobe für Deutschland Aus Dem Kinder-und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (Kiggs). Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2007, 50, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bös, K.; Schlenker, L.; Büsch, D.; Lämmle, L.; Müller, H.; Oberger, J.; Seidel, I.; Tittlbach, S. Deutscher Motorik Test 6–18: (Dmt 6–18); Czwalina: Hamburg, Germany, 2009; Volume 186. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Russell, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W. Validity and Reliability of the Wristband Activity Monitor in Free-Living Children Aged 10–17 Years. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2019, 32, 812–822. [Google Scholar]

- KidsTUMove Goes Europe—Cordially fit. Available online: https://Ktm.Infoproject.Eu (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Etschenberg, K.; Kösters, W. Chronische Erkrankungen Als Problem und Thema in Schule und Unterricht. Handreichung für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer der Klassen 1–10; Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Cologne, Germany, 2001; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine, S.; Sticker, E.J.; Dordel, S.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B. Bewegung, Spiel und Sport Mit Herzkranken Kindern. Dtsch. Arztebl. 2007, 104, 563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, N.; Gaser, D.; Fritz, R.O.; Sitzberger, C. The COVID 19 Pandemic and the Challenge of Growing up in Children with Congenital Heart Defects and Adolescents. Cardiol. Young 2022, S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöcker, N.; Oberhoffer, R.; Ewert, P. Kidstumove: Background and Outlook for Healthy Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Congenital Heart Diseases. Cardiol. Young 2017, 27 (Suppl. 2), 141. [Google Scholar]

- Sawin, K.J.; Lannon, S.L.; Austin, J.K. Camp Experiences and Attitudes toward Epilepsy: A Pilot Study. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2001, 33, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Békési, A.; Török, S.; Kökönyei, G.; Bokrétás, I.; Szentes, A.; Telepóczki, G.; European KIDSCREEN Group Ravens-Sieberer@ uke. Uni-Hamburg. de. Health-Related Quality of Life Changes of Children and Adolescents with Chronic Disease after Participation in Therapeutic Recreation Camping Program. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2011, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, G.; Gormley, M.; MacLachlan, M. Outcomes Associated with Participation in a Therapeutic Recreation Camping Programme for Children from 15 European Countries: Data from the ‘Barretstown Studies’. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, A.R.; Moothathamby, N.; Naganathan, M.; Huynh, E.; Moola, F.J. “A Place to Call Our Own”: The Impact of Camp Experiences on the Psychosocial Wellbeing of Children and Youth Affected by Cancer—A Narrative Review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, I.; Stinson, J.; Stevens, B. The Effects of Camp on Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Chronic Illnesses: A Review of the Literature. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 22, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallander, J.L.; Siegel, L.J. Adolescent Health Problems: Behavioral Perspectives; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wallander, J.L.; Varni, J.W. Social Support and Adjustment in Chronically Ill and Handicapped Children. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1989, 17, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Weiss, R.T.; Rapoff, M.A.; Varni, J.W.; Lindsley, C.B.; Olson, N.Y.; Madson, K.L.; Bernstein, B.H. Daily Hassles and Social Support as Predictors of Adjustment in Children With Pediatric Rheumatic Disease. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2002, 27, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, H.L.; Rosnov, D.L.; Koontz, D.; Roberts, M.C. Camping Programs for Children with Chronic Illness as a Modality for Recreation, Treatment, and Evaluation: An Example of a Mission-Based Program Evaluation of a Diabetes Camp. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2006, 13, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, R.B.; Fornaciari, G.M.; Foster, K.N.; Bay, C.R.; Wadsworth, M.M.; Wood, M.; Caruso, D.M. Impact of a Pediatric Residential Burn Camp Experience on Burn Survivors’ Perceptions of Self and Attitudes Regarding the Camp Community. J. Burn. Care Res. 2007, 28, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.A.; Pearman, D. Therapeutic Recreation Camps: An Effective Intervention for Children and Young People with Chronic Illness? Arch. Dis. Child. 2009, 94, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, R. Tackling Chronic Disease in Europe: Strategies, Interventions and Challenges; WHO Regional Office Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesverband Herzkranke Kinder, e.V. BVHK. Available online: https://bvhk.de/angebote-hilfe/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Krebshilfe, Deutsche. Available online: https://www.kinderkrebshilfe.de/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Kinderherzen, Fördergemeinschaft Deutscher Kinderherzzentren e.V. Available online: https://www.kinderherzen.de/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Moons, P.; Barrea, C.; De Wolf, D.; Gewillig, M.; Massin, M.; Mertens, L.; Ovaert, C.; Suys, B.; Sluysmans, T. Changes in Perceived Health of Children with Congenital Heart Disease after Attending a Special Sports Camp. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2006, 27, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shafran, R.; Bennett, S.; Jolly, A. An Investigation into the Psychosocial Impact of Therapeutic Recreation Summer Camp for Youth with Serious Illness and Disability. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Longmuir, P.E.; Messy, R.; Messy, R.; Lai, L. “Like Any Other Camp”: Experiences and Lessons Learned from an Integrated Day Camp For Children With Heart Disease. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 27, e12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, A. Summer Camp for Children And Adolescents with Chronic Conditions. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 41, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

| Modular Program | Topic | Identified Challenges and Constraints | Possible Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular sports activities: Move it—integrative sports group, KidsTUMove climbing group | Location | Sports hall availability | Integration into existing sports clubs |

| Personnel | Qualified staff | Recruitment of trainers through associations, education facilities, and universities (e.g., integration into teaching) | |

| Financial Resources | Costs for material and qualified trainers | Raising donations in relation to specific items; course fees or membership fees; health insurance support | |

| Acquisition | Limited attention from the public/community | Increase visibility through flyers, website, personal network; dissemination strategy development; participation in local events, conferences and congresses | |

| Medical Care | Medical emergencies, participant-related selection criteria: >3-6 months post-operation, sports clearance certificate, no psychological impairments, independent daily living (no caregiving activities assumed) | Pediatrician at venue; first aid kit and defibrillator available; close collaboration with parents | |

| Insurance | Vulnerable participants (higher sum insured), accidents | Insurance through the association with special medical conditions | |

| Data Protection | High data security and duty of confidentiality | Data encryption and personal access guidelines | |

| Schedule | Conflict with school and other leisure activities | Consideration of school commitments, consultation with parents, adaptable schedule | |

| Evaluation | Effectiveness of the program | Status quo test and longitudinal analysis in the course of training (quality of life, motor skills, physical activity) | |

| Camps and Events: KidsTUMove summer and winter camps, KidsTUMove weekend events | Location | Suitable accommodation and sports facilities with opportunities for indoor and outdoor sports courses. Easily accessible medical care near the venue | Cooperation with foundations and clubs that provide their facilities |

| Personnel | Qualified staff | Recruitment of trainers through associations, universities (e.g., integration into teaching); third-party projects; volunteers | |

| Financial Resources | Integration of long-term sponsors, regional supporters | Long-term cooperation with foundations, associations and parents’ initiatives; participant fees | |

| Medical Care | Availability of pediatrician. Continuous and monitored administration of medication. Participant-related special selection criteria: >3-6 months post-operation, sports clearance certificate, no psychological impairments, independent daily living (no caregiving activities assumed) | 24-h doctor available at venue; medication plan and administration by medical staff on-site; clinics/emergency services informed near venue; contact with medical care centers and treating physicians; emergency equipment (e.g., defibrillator) on-site | |

| Insurance | Vulnerable participants (higher sum insured), accidents | External insurance company for participant insurance | |

| Acquisition | Limited attention from the public/community | Increase visibility through flyers, website, personal network; dissemination strategy development; participation in local events, conferences and congresses | |

| Data Protection | High data security and duty of confidentiality | Data encryption and personal access guidelines | |

| Evaluation | Effectiveness of the program, Quality analysis | Pre/post tests (quality of life, satisfaction, motor skills, physical activity), supervision | |

| Online activities: KidsTUMove goes online! | Location | Adequate space with good lighting, available capacity, and sufficient electrical outlets | Cooperation with universities or foundations |

| Personnel | Qualified staff | Recruitment of trainers, students, and trainees through associations or university (e.g., through integration into teaching); third-party projects; volunteers | |

| Financial Resources | Costs for internet platforms, media equipment and technical expertise of employees | Equipment on a donation basis; equipment rental; cooperation with foundations | |

| Medical Care | Supervision difficult: no personal contact | Safety guidelines for supervised online training | |

| Schedule | Timing, compatible with school schedules, pandemic issues | Hybrid offer; live sessions; dispatching material packages for the offerings | |

| Acquisition | Expansion of target group, accessibility of participants | Homepage setup; using network | |

| Data Protection | High data security and duty of confidentiality, internet security, and traceability on the web | Data encryption and personal access guidelines | |

| Evaluation | Effectiveness of the program, Quality analysis | Progress controls via online forms (quality of life, satisfaction, physical activity) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stöcker, N.; Gaser, D.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Sitzberger, C. KidsTUMove—A Holistic Program for Children with Chronic Diseases, Increasing Physical Activity and Mental Health. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133791

Stöcker N, Gaser D, Oberhoffer-Fritz R, Sitzberger C. KidsTUMove—A Holistic Program for Children with Chronic Diseases, Increasing Physical Activity and Mental Health. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133791

Chicago/Turabian StyleStöcker, Nicola, Dominik Gaser, Renate Oberhoffer-Fritz, and Christina Sitzberger. 2024. "KidsTUMove—A Holistic Program for Children with Chronic Diseases, Increasing Physical Activity and Mental Health" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133791

APA StyleStöcker, N., Gaser, D., Oberhoffer-Fritz, R., & Sitzberger, C. (2024). KidsTUMove—A Holistic Program for Children with Chronic Diseases, Increasing Physical Activity and Mental Health. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133791