Patients with a Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) Diagnosed with ECG-Gated Cardiac Multislice Computed Tomography—Analysis of the Reasons for Referral, Classification of Morphological Phenotypes, Co-Occurring Cardiovascular Abnormalities, and Coronary Artery Stenosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Computed Tomography Protocol

2.3. Analysis of Reasons for Referral for Cardiac CT in Patients with BAV

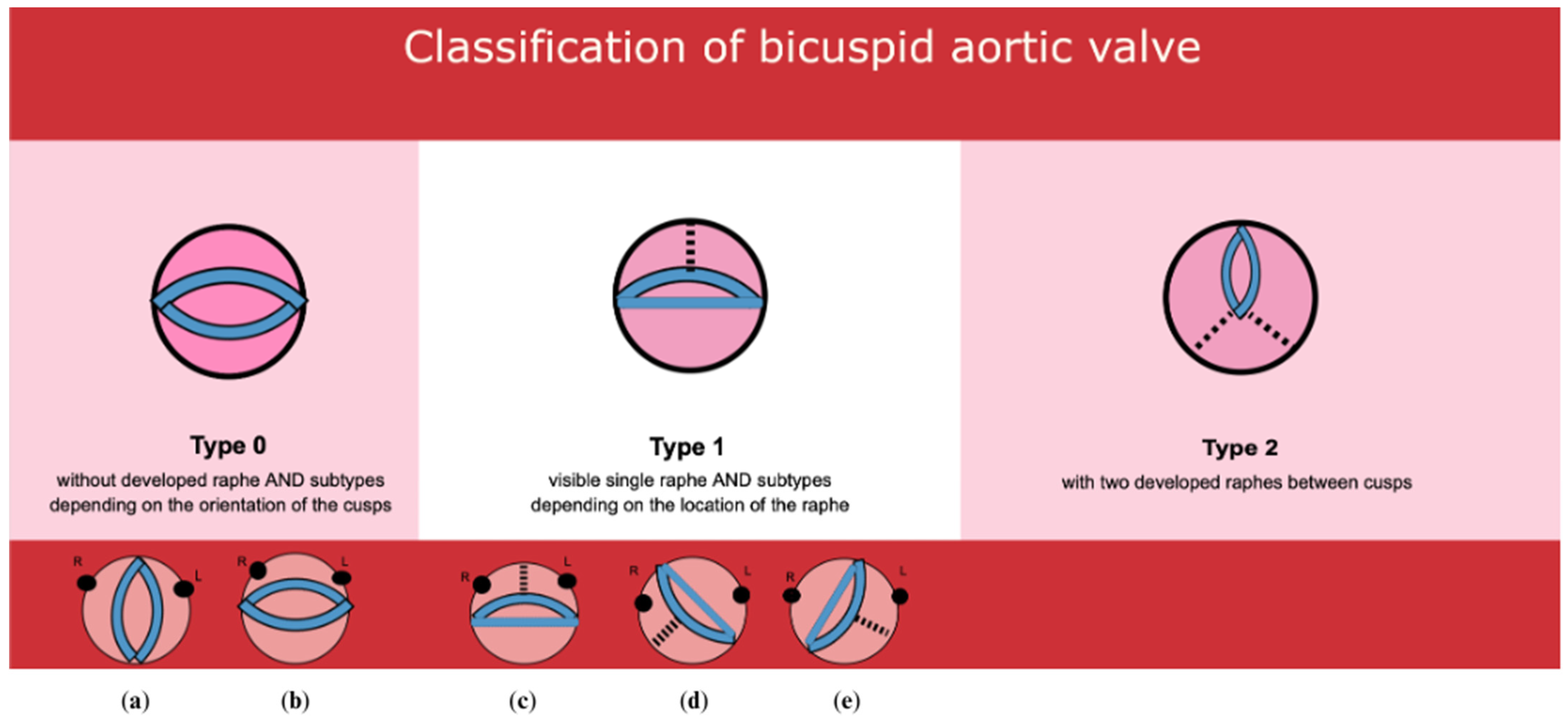

2.4. BAV Classification

2.5. Classification of Cardiovascular Abnormalities Coexisting with BAV

2.6. Coronary Stenosis Severity Score

- Category 0 (corresponding to CAD-RADS 0)—no atherosclerotic lesions, stenosis 0%;

- Category 1 (corresponding to CAD-RADS 1–2)—insignificant lesions, stenosis 1–49%;

- Category 2 (corresponding to CAD-RADS 3)—less severe significant lesions, stenosis 50–69%;

- Category 3 (corresponding to CAD-RADS 4)—significant lesions, stenosis 70–99%;

- Category 4 (corresponding to CAD-RADS 5)—total coronary occlusion, 100% stenosis.

- Calcium score 1–100 (P1 according to CAD-RADS)—mild amount of plaque;

- Calcium score 101–300 (P2 according to CAD-RADS)—moderate amount of plaque;

- Calcium score 301–999 (P3 according to CAD-RADS)—severe amount of plaque;

- Calcium score > 1000 (P4 according to CAD-RADS)—extensive amount of plaque.

2.7. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Structure of the Study Group According to the Sievers–Schmidtke Classification

3.3. Indications for ECG-Gated Cardiac CT

3.4. BAV and Accompanying Cardiovascular Defects in Cardiac CT

3.5. Coronary Artery Stenosis in Patients with BAV

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bravo-Jaimes, K.; Prakash, S.K. Genetics in bicuspid aortic valve disease: Where are we? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.I.; Kaplan, S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.D.; Crawford, T.; Magruder, J.T.; Alejo, D.E.; Hibino, N.; Black, J.; Dietz, H.C.; Vricella, L.A.; Cameron, D.E. Cardiovascular operations for Loeys-Dietz syndrome: Intermediate-term results. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 153, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, A.S.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Zackai, E.H.; Goldmuntz, E. Aortic root dilation in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2009, 149A, 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niaz, T.; Poterucha, J.T.; Olson, T.M.; Johnson, J.N.; Craviari, C.; Nienaber, T.; Palfreeman, J.; Cetta, F.; Hagler, D.J. Characteristic Morphologies of the Bicuspid Aortic Valve in Patients with Genetic Syndromes. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2018, 31, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strande, N.T.; Riggs, E.R.; Buchanan, A.H.; Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; DiStefano, M.; Dwight, S.S.; Goldstein, J.; Ghosh, R.; Seifert, B.A.; Sneddon, T.P.; et al. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Gene-Disease Associations: An Evidence-Based Framework Developed by the Clinical Genome Resource. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, I.; Albuisson, J.; Goudot, G.; Carmi, S.; Shpitzen, S.; Messas, E.; Gilon, D.; Durst, R. Bicuspid Aortic Valve: Genetic and Clinical Insights. Aorta 2021, 9, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, R.B.; Martin, L.J.; Rame-Gowda, S.; Tabangin, M.E.; Cripe, L.H.; Benson, D.W. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome links to chromosomes 10q and 6q and is genetically related to bicuspid aortic valve. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.M.; Gallego, P.; Gonzalez, A.; Aroca, A.; Bret, M.; Mesa, J.M. Risk factors for aortic complications in adults with coarctation of the aorta. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minette, M.S.; Sahn, D.J. Ventricular septal defects. Circulation 2006, 114, 2190–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasuski, R.A. When and how to fix a ‘hole in the heart’: Approach to ASD and PFO. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2007, 74, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsey, J.T.; Elmasry, O.A.; Martin, R.P. Patent arterial duct. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2009, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, W.C. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. A study of 85 autopsy cases. Am. J. Cardiol. 1970, 26, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.-M. The anatomopathology of bicuspid aortic valve. Folia Morphol. 2011, 70, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sabet, H.Y.; Edwards, W.D.; Tazelaar, H.D.; Daly, R.C. Congenitally bicuspid aortic valves: A surgical pathology study of 542 cases (1991 through 1996) and a literature review of 2,715 additional cases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1999, 74, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, H.-H.; Schmidtke, C. A classification system for the bicuspid aortic valve from 304 surgical specimens. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 133, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelena, H.I.; Corte, A.D.; Evangelista, A.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Edwards, W.D.; Roman, M.J.; Devereux, R.B.; Fernández, B.; Asch, F.M.; Barker, A.J.; et al. International consensus statement on nomenclature and classification of the congenital bicuspid aortic valve and its aortopathy, for clinical, surgical, interventional and research purposes. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 60, 448–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, B.M.; Lewin, M.B.; Stout, K.K.; Gill, E.; Prueitt, A.; Byers, P.H.; Otto, C.M. The bicuspid aortic valve: An integrated phenotypic classification of leaflet morphology and aortic root shape. Heart 2008, 94, 1634–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.J.; Shin, J.K.; Chee, H.K.; Kim, J.S.; Ko, S.M. Characteristics of aortic valve dysfunction and ascending aorta dimensions according to bicuspid aortic valve morphology. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 2103–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzmetov, M.; Shah, J.J.; Fortuna, R.S.; Welke, K.F. The Association Between Aortic Valve Leaflet Morphology and Patterns of Aortic Dilation in Patients with Bicuspid Aortic Valves. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 99, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.K.; Delgado, V.; Poh, K.K.; Regeer, M.V.; Ng, A.C.; McCormack, L.; Yeo, T.C.; Shanks, M.; Parent, S.; Enache, R.; et al. Prognostic Implications of Raphe in Bicuspid Aortic Valve Anatomy. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Simpson, T.F.; Akhavein, R.; Rajotte, K.; Weller, S.; Fuss, C.; Song, H.K.; Golwala, H.; Zahr, F.; Chadderdon, S.M. Hemodynamic and Conduction System Outcomes in Sievers Type 0 and Sievers Type 1 Bicuspid Aortic Valves Post Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Struct. Heart 2021, 5, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, F.A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Siepe, M. Pathophysiological implications of different bicuspid aortic valve configurations. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 735829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, B.; Durán, A.C.; Fernández-Gallego, T.; Fernández, M.C.; Such, M.; Arqué, J.M.; Sans-Coma, V. Bicuspid aortic valves with different spatial orientations of the leaflets are distinct etiological entities. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2312–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaoutakis, G.J.; Sultan, I.; Siki, M.; Bavaria, J.E. Bicuspid aortic valve repair: Systematic review on long-term outcomes. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 8, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.T.; Roman, M.J.; Mogtadek, A.H.; Devereux, R.B. Association of aortic dilation with regurgitant, stenotic and functionally normal bicuspid aortic valves. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 19, 238–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sucu, M.; Davutoğlu, V.; Özer, O.; Başpınar, O.; Aksoy, M.; Kılıç, M. Bicuspid Aortic Valve Prevalence In A Large Series Of Echocardiograms In The Area Of Frequent Consanguineous Marriage. Eur. J. Ther. 2009, 15, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Pasic, M.; Schaffarzyk, R.; Siniawski, H.; Knollmann, F.; Meyer, R.; Hetzer, R. Reduction aortoplasty for dilatation of the ascending aorta in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2002, 73, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzi, F.; Valentini, F.; Anselmi, F.; Cavigli, L.; Bandera, F.; Benfari, G.; D’Andrea, A.; Di Salvo, G.; Esposito, R.; Evola, V.; et al. Bicuspid aortic valve and sports: From the echocardiographic evaluation to the eligibility for sports competition. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Ohtaki, E.; Misu, K.; Tohbaru, T.; Asano, R.; Nagayama, M.; Kitahara, K.; Umemura, J.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Kawase, M.; et al. Etiology of aortic valve disease and recent changes in Japan: A study of 600 valve replacement cases. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002, 86, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, C.C.; Eykyn, S.J. Bicuspid aortic valve—A silent danger: Analysis of 50 cases of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelena, H.I.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Topilsky, Y.; Messika-Zeitoun, D.; Della Corte, A.; Evangelista, A.; Schäfers, H.-J.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. The Bicuspid Aortic Valve Condition: The Critical Role of Echocardiography and the Case for a Standard Nomenclature Consensus. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 61, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.L.; Stinson, W.A.; Veinot, J.P. Reliability of transthoracic echocardiography in the assessment of aortic valve morphology: Pathological correlation in 178 patients. Can. J. Cardiol. 1999, 15, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.K.F.; Delgado, V.; Bax, J.J. Bicuspid Aortic Valve: What to Image in Patients Considered for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, e005987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakar, T.S.; Tülüce, K.; Şimşek, E.Ç.; Şafak, Ö.; Ökten, M.Ş.; Yapan Emren, Z.; Emren, S.V.; Kocabaş, U.; Bayata, S.; Nazlı, C. Assessment of bicuspid aortic valve phenotypes and associated pathologies: A transesophageal echocardiographic study. Turk. Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2017, 45, 690–701. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E. Echocardiographic evaluation of the aortic valve. In UpToDate; Manning, W.J., Yeon, S.B., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/5295 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Mathur, S.K.; Singh, P. Transoesophageal echocardiography related complications. Indian J. Anaesth. 2009, 53, 567–574. [Google Scholar]

- Alkadhi, H.; Leschka, S.; Trindade, P.T.; Feuchtner, G.; Stolzmann, P.; Plass, A.; Baumueller, S. Cardiac CT for the differentiation of bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves: Comparison with echocardiography and surgery. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; McEvoy, S.H.; Iyengar, S.; Feuchtner, G.; Cury, R.C.; Roobottom, C.; Baumueller, S.; Alkadhi, H.; Dodd, J.D. Bicuspid aortic valves: Diagnostic accuracy of standard axial 64-slice chest CT compared to aortic valve image plane ECG-gated cardiac CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2014, 83, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, J.; Chandrashekhar, Y.; Ahmadi, A.; Abbara, S.; Berman, D.S.; Blankstein, R.; Leipsic, J.; Newby, D.; Nicol, E.D.; Nieman, K.; et al. SCCT 2021 Expert Consensus Document on Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography: A Report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2021, 15, 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierro, A.; Cilla, S.; Totaro, A.; Ienco, V.; Sacra, C.; De Filippo, C.M.; Sallustio, G. ECG-gated CT angiography of the thoracic aorta: The importance of evaluating the coronary arteries. Clin. Radiol. 2018, 73, 983.e1–983.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.S.; Strange, G.; Playford, D.; Stewart, S.; Celermajer, D.S. Characteristics of Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease and Stenosis: The National Echo Database of Australia. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, A.; Gallego, P.; Calvo-Iglesias, F.; Bermejo, J.; Robledo-Carmona, J.; Sánchez, V.; Saura, D.; Arnold, R.; Carro, A.; Maldonado, G.; et al. Anatomical and clinical predictors of valve dysfunction and aortic dilation in bicuspid aortic valve disease. Heart 2018, 104, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.W.; Muchnik, R.D.; Ogunsua, A.; Kundu, A.; Lakshmanan, S.; Shah, N.; Dickey, J.B.; Gentile, B.A.; Pape, L.A. Serial echocardiography for valve dysfunction and aortic dilation in bicuspid aortic valves. Echocardiography 2021, 38, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, M.; Kahler-Quesada, A.; Mori, M.; Yousef, S.; Geirsson, A.; Vallabhajosyula, P. Progression of aortic stenosis in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. J. Card. Surg. 2021, 36, 4665–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beppu, S.; Suzuki, S.; Matsuda, H.; Ohmori, F.; Nagata, S.; Miyatake, K. Rapidity of progression of aortic stenosis in patients with congenital bicuspid aortic valves. Am. J. Cardiol. 1993, 71, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, F.E.C.M.; Van der Linden, N.; Thomassen, A.L.L.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; Meex, S.J.R.; Kietselaer, B.L.J.H. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants in bicuspid aortic dilatation: Results from a longitudinal observational study. Medicine 2016, 95, e5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, A.; Bancone, C.; Buonocore, M.; Dialetto, G.; Covino, F.E.; Manduca, S.; Scognamiglio, G.; D’Oria, V.; De Feo, M. Pattern of ascending aortic dimensions predicts the growth rate of the aorta in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avadhani, S.A.; Martin-Doyle, W.; Shaikh, A.Y.; Pape, L.A. Predictors of ascending aortic dilation in bicuspid aortic valve disease: A five-year prospective study. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibevski, S.; Ruzmetov, M.; Plate, J.F.; Scholl, F.G. The Impact of Bicuspid Aortic Valve Leaflet Fusion Morphology on the Ascending Aorta and on Outcomes of Aortic Valve Replacement. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2023, 50, e217831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.S.; Mallidi, H.R.; Lee, R.S.; Sheehan, M.P.; Liang, D.; Fleischman, D.; Herfkens, R.; Mitchell, R.S.; Miller, D.C. The aortopathy of bicuspid aortic valve disease has distinctive patterns and usually involves the transverse aortic arch. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 135, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Foley, T.A.; Bonnichsen, C.R.; Maurer, M.J.; Goergen, K.M.; Nkomo, V.T.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; Williamson, E.E.; Michelena, H.I. Transthoracic Echocardiography versus Computed Tomography for Ascending Aortic Measurements in Patients with Bicuspid Aortic Valve. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Otto, C. Bicuspid Aortic Valve and Aortopathy: See the First, Then Look at the Second. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Coronary artery anomalies: An entity in search of an identity. Circulation 2007, 115, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, G.M.; Nazarian, I.H.; Bulkley, B.H. Association of left dominant coronary arterial system with congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Am. J. Cardiol. 1978, 42, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bild, D.E.; Detrano, R.; Peterson, D.; Guerci, A.; Liu, K.; Shahar, E.; Ouyang, P.; Jackson, S.; Saad, M.F. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2005, 111, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, A.; Alfieri, O.; Andreotti, F.; Antunes, M.J.; Barón-Esquivias, G.; Baumgartner, H.; Borger, M.A.; Carrel, T.P.; De Bonis, M.; Evangelista, A.; et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2451–2496. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling, J.S.; Lubat, E. Forme fruste or ‘Incomplete’ bicuspid aortic valves with very small raphes: The prevalence of bicuspid valve and its significance may be underestimated. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 184, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Polguj, M.; Szymczyk, E.; Bakoń, L.; Pacho, R.; Stefańczyk, L. Assessment of aortic valve in regard to its anatomical variants morphology in 2053 patients using 64-slice CT retrospective coronary angiography. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Kim, W.-K.; Dhoble, A.; Milhorini Pio, S.; Babaliaros, V.; Jilaihawi, H.; Pilgrim, T.; De Backer, O.; Bleiziffer, S.; Vincent, F.; et al. Bicuspid Aortic Valve Morphology and Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Choi, B.H.; Chee, H.K.; Kim, J.S.; Ko, S.M. Aortic Valve Dysfunction and Aortopathy Based on the Presence of Raphe in Patients with Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, S. ECG-Gated Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Doctoral Dissertation, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland, 2014. Available online: https://ppm.umlub.pl/info/achievement/UML9f856c6acab24c8bbfe35683244350e7/ (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Bialkowski, J.; Szkutnik, M.; Glowacki, J.; Fiszer, R. Coarctation of the aorta—Clinical picture and therapeutic options. Post. Cardiol. Interw. 2010, 6, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, S.M.; Sanders, S.P.; Khairy, P.; Jenkins, K.J.; Gauvreau, K.; Lang, P.; Simonds, H.; Colan, S.D. Morphology of bicuspid aortic valve in children and adolescents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 1648–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tullio, M.R.; Homma, S. Patent foramen ovale and stroke: What should be done? Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2009, 16, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukić, F.; Miljko, M.; Vegar-Zubović, S.; Behmen, A.; Arapović, A.K. Prevalence of coronary artery anomalies detected by coronary CT angiography in Canton Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 830–834. [Google Scholar]

- Smettei, O.A.; Sayed, S.; Abazid, R.M. The prevalence of coronary artery anomalies in Qassim Province detected by cardiac computed tomography angiography. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2017, 29, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirasapalli, C.N.; Christopher, J.; Ravilla, V. Prevalence and spectrum of coronary artery anomalies in 8021 patients: A single centre study in South India. Indian Heart J. 2018, 70, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, A.; Babai, L.; Rudas, L.; Gaál, T.; Horváth, T.; Tálosi, L.; Tóth, K.; Sárváry, L.; Szász, K. Epidemiology of congenital coronary artery anomalies: A coronary arteriography study on a central European population. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Diagn. 1997, 42, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedak, P.W.; Verma, S.; David, T.E.; Leask, R.L.; Weisel, R.D.; Butany, J. Clinical and pathophysiological implications of a bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation 2002, 106, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michałowska, I.M.; Hryniewiecki, T.; Kwiatek, P.; Stokłosa, P.; Swoboda-Rydz, U.; Szymański, P. Coronary Artery Variants and Anomalies in Patients with Bicuspid Aortic Valve. J. Thorac. Imaging 2016, 31, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenraadt, W.M.C.; Tokmaji, G.; DeRuiter, M.C.; Vliegen, H.W.; Scholte, A.J.H.A.; Siebelink, H.M.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; de Graaf, M.A.; Wolterbeek, R.; Mulder, B.J.; et al. Coronary anatomy as related to bicuspid aortic valve morphology. Heart 2016, 102, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, S.; Petersen, J.; Reichenspurner, H.; Girdauskas, E. The impact of coronary anomalies on the outcome in aortic valve surgery: Comparison of bicuspid aortic valve versus tricuspid aortic valve morphotype. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 26, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFaria, Y.D. Coronary artery variants and bicuspid aortic valve disease: Gaining insight into genetic underpinnings. Heart 2018, 104, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhajosyula, S.; Fuchs, M.; Yang, L.-T.; Gulati, R.; Klarich, K.; Michelena, H. Anomalous coronary artery origin from the opposite sinus in patients with bicuspid aortic valve—Comparison with tricuspid aortic valve. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.-L.; Bhalla, S.; Bierhals, A.; Gutierrez, F. MDCT of partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) in adults. J. Thorac. Imaging 2009, 24, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Lluri, G. Coronary Artery Dominance and Cardiovascular Pathologies in Patients with Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 363, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, P.; Cavallotti, L.; Songia, P.; Di Minno, A.; Ambrosino, P.; Mammana, L.; Parolari, A.; Alamanni, F.; Tremoli, E.; Di Minno, M.N. Impact of Valve Morphology on the Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuchtner, G.; Bleckwenn, S.; Stoessl, L.; Plank, F.; Beyer, C.; Bonaros, N.; Schachner, T.; Senoner, T.; Widmann, G.; Gollmann-Tepeköylü, C.; et al. Bicuspid Aortic Valve Is Associated with Less Coronary Calcium and Coronary Artery Disease Burden. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Z.; Guan, L.; Mu, Y. Association between bicuspid aortic valve phenotype and patterns of valvular dysfunction: A meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2021, 44, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohmann, R.F.; Lauten, P.; Seitz, P.; Krieghoff, C.; Lücke, C.; Gottschling, S.; Mende, M.; Weiß, S.; Wilde, J.; Kiefer, P.; et al. Combined Coronary CT-Angiography and TAVI-Planning: A Contrast-Neutral Routine Approach for Ruling-out Significant Coronary Artery Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of the Study Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 0 (n = 42) | Type 1 R-L * (n = 501) | Type 1 R-N + 1 L-N * (n = 100) | Type 2 (n = 57) | p | |

| Age [years], Me (Min–Max) | 48.5 (3–85) | 56 (7–88) | 54 (1–80) | 30.5 (6–76) | <0.001 |

| Sex–Males, n (%) | 30 (71.4%) | 342 (68.3%) | 60 (60.0%) | 41 (71.9%) | 0.320 |

| BMI, Me (Min–Max) | 26.1 (16.0–39.1) | 28.1 (11.3–41.9) | 26.6 (15.6–38.4) | 24.8 (15.4–39.7) | 0.070 |

| Ejection fraction [%], Me (Min–Max) | 59 (33–87) | 62.5 (16–85) | 63 (16–83) | 63.5 (19–78) | 0.236 |

| End-diastolic volume [ml], Me (Min–Max) | 164.5 (60–453) | 172 (59–508) | 159 (12–643) | 174 (57–486) | 0.258 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 20 (47.6%) | 221 (44.1%) | 48 (48.0%) | 25 (43.9%) | 0.882 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (9.5%) | 54 (10.8%) | 16 (16.0%) | 6 (10.5%) | 0.481 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 10 (23.8%) | 75 (15.0%) | 10 (10.0%) | 6 (10.5%) | 0.145 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 10 (23.8%) | 119 (23.8%) | 22 (22.0%) | 13 (22.8%) | 0.984 |

| Indications for ECG-Gated Cardiac CT in Patients with BAV | Overall (n = 700), n (%) | Males (n = 473), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 219 (31.1%) | 127 (26.8%) |

| 64 (9.1%) | 40 (8.5%) |

| 54 (7.7%) | 40 (8.5%) |

| 42 (6.0%) | 31 (6.6%) |

| 105 (15.0%) | 85 (18.0%) |

| 12 (1.7%) | 6 (1.3%) |

| 53 (7.6%) | 39 (8.2%) |

| 39 (5.6%) | 33 (7.0%) |

| 11 (1.6%) | 6 (1.3%) |

| 8 (1.1%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| 12 (1.7%) | 10 (2.1%) |

| 10 (1.4%) | 5 (1.1%) |

| 18 (2.6%) | 15 (3.2%) |

| 20 (2.9%) | 8 (1.7%) |

| 33 (4.7%) | 26 (5.5%) |

| The Most Common Indications for ECG-Gated Cardiac CT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with BAV in ECG-Gated Cardiac CT (n = 700) | |||||

| ≤40 years (n = 203) | n (%) | 41–60 years (n = 271) | n (%) | >60 years (n = 226) | n (%) |

| Suspicion or postoperative assessment of congenital cardiovascular defects excluding BAV—category 2 | 49 (24.1%) | Suspected coronary artery disease—category 1 | 113 (41.7%) | Suspected coronary artery disease—category 1 | 99 (43.8%) |

| Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 32 (15.8%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 48 (17.7%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 25 (11.0%) |

| Verification of BAV presence—category 3 | 29 (14.3%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography without initial diagnosis of BAV or aortic valve disease—category 4 | 24 (8.9%) | Assessment of the heart and the aorta before TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation)—category 14 | 17 (7.5%) |

| Parametric assessment of aortic stenosis or aortic insufficiency coexisting with BAV—category 8 | 26 (12.8%) | Parametric assessment of acquired aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) without an initial diagnosis of BAV—category 7 | 15 (5.5%) | Parametric assessment of acquired aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) without an initial diagnosis of BAV—category 7 | 15 (6.6%) |

| Parametric assessment of acquired aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) without an initial diagnosis of BAV —category 7 | 23 (11.3%) | Verification of BAV presence—category 3 | 15 (5.5%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography without an initial diagnosis of BAV or aortic valve disease—category 4 | 13 (5.8%) |

| Females with BAV in ECG-gated cardiac CT (n = 227) | |||||

| ≤40 years (n = 54) | n (%) | 41–60 years (n = 85) | n (%) | >60 years (n = 88) | n (%) |

| suspicion or postoperative assessment of congenital cardiovascular defects excluding BAV—category 2 | 18 (33.3%) | Suspected coronary artery disease—category 1 | 46 (54.1%) | Suspected coronary artery disease—category 1 | 43 (48.9%) |

| verification of BAV presence—category 3 | 8 (14.8%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography without an initial diagnosis of BAV or aortic valve disease—category 4 | 8 (9.4%) | Assessment of the heart and the aorta before TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation)—category 14 | 11 (12.5%) |

| dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 7 (13.0%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 8 (9.4%) | Parametric assessment of acquired aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) without an initial diagnosis of BAV—category 7 | 7 (8.0%) |

| Males with BAV in ECG-gated cardiac CT (n = 473) | |||||

| ≤40 years (n = 149) | n (%) | 41–60 years (n = 186) | n (%) | >60 years (n = 138) | n (%) |

| suspicion or postoperative assessment of congenital cardiovascular defects excluding BAV—category 2 | 31 (20.8%) | Suspected coronary artery disease—category 1 | 67 (36.0%) | Suspected coronary artery disease—category 1 | 56 (40.6%) |

| dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 25 (16.8%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 40 (21.5%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography with accompanying aortic valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency) or bicuspid aortic valve—category 5 | 20 (14.5%) |

| parametric assessment of aortic stenosis or aortic insufficiency coexisting with BAV—category 8 | 22 (14.8%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography without an initial diagnosis of BAV or aortic valve disease—category 4 | 16 (8.6%) | Dilated ascending aorta in echocardiography without an initial diagnosis of BAV or aortic valve disease—category 4 | 10 (7.2%) |

| Cardiovascular Abnormalities Accompanying BAV in CCTA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I. Cardiovascular defects | n (%) | Group II. Coronary artery anomalies | n (%) | Group III. Other cardiovascular abnormalities | n (%) |

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) | 30 (4.3%) | (1) Anomalies of origin | 108 *** | Patent foramen ovale (PFO) | 105 (15.0%) |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 25 (3.6%) | High take-off | 45 (6.4%) | Atrial septal aneurysm | 52 (7.4%) |

| Atrial septal defect (ASD) | 18 (2.6%) | Paracommissural orifice | 31 (4.4%) | Accessory left atrial appendage | 35 (5.0%) |

| Partial absence of the pericardium | 10 (1.4%) | Absence of left main coronary artery (LMCA) | 19 (2.7%) | Bachmann bundle leak | 27 (3.9%) |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch | 8 (1.1%) | Origin of coronary artery or branch from opposite sinus | 9 (1.3%) | Left ventricular diverticulum | 26 (3.7%) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) | 7 (1.0%) | Origin of circumflex artery (LCx) from right coronary artery (RCA) | 4 (0.6%) | Arteria lusoria | 17 (2.4%) |

| Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) | 7 (1.0%) | (2) Anomalies of termination | 3 *** | Common origin of brachiocephalic and left common carotid arteries | 13 ** |

| Persistent left superior vena cava | 5 (0.7%) | Coronary arteriovenous fistula | 3(0.4%) | Left common carotid artery arising from the brachiocephalic trunk | 9 ** |

| Transposition of great arteries (TGA) | 2 (0.3%) | ||||

| Others * | 3 (0.4%) | ||||

| Total number of cardiovascular defects | 115 *** | Total number of coronary artery anomalies | 111 *** | Total number of other cardiovascular abnormalities | 284 *** |

| Characteristics of Study Group | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | 111 (23.5%) | 58 (25.6%) | ||||

| Number of clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 143 | 83 | ||||

| Number of defects/person in patients with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 1.29 | 1.43 | ||||

| Number of defects/person in the whole group | 0.30 | 0.37 | ||||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation in the group with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 17.1% | 25.9% | ||||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation in the whole group | 14.4% | 15.0% | ||||

| Most common clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | High take-off | 34 (7.2%) | Paracommissural orifice | 17 (7.5%) | ||

| VSD | 25 (5.3%) | Coarctation of the aorta | 11 (4.9%) | |||

| Absence of LMCA | 15 (3.2%) | High take-off | 11 (4.9%) | |||

| Coarctation of the aorta | 14 (3.0%) | ASD | 8 (3.5%) | |||

| Paracommissural orifice | 14 (3.0%) | PAPVR | 7 (3.1%) | |||

| Defects with different prevalences in females and males | Paracommissural orifice, n (%) | 14 (3.0%) | 17 (7.5%) | p = 0.010 | ||

| PAPVR, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (3.1%) | p < 0.001 | |||

| VSD *, n (%) | 25 (5.6%) | 5 (2.2%) | p = 0.059 | |||

| Characteristics of the Study Group | Type 0 (n = 42) | Type 1 (n = 601) | Type 2 (n = 57) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | 15 (35.7%) | 143 (23.8%) | 11 (19.3%) | |||

| Number of clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 22 | 187 | 17 | |||

| Number of defects/person in patients with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 1.47 | 1.30 | 1.54 | |||

| Number of defects/person in the whole group | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.30 | |||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation in the group with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 40.0% | 17.5% | 27.3% | |||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation in the whole group | 21.4% | 13.6% | 19.3% | |||

| Most common clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | High take-off | 5 (11.9%) | High take-off | 33 (5.5%) | High take-off | 7 (13.5%) |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 4 (9.5%) | Paracommissural orifice | 29 (4.8%) | VSD | 2 (3.8%) | |

| VSD | 2 (4.8%) | VSD | 25 (4.2%) | PDA | 2 (3.8%) | |

| ASD | 2 (4.8%) | Coarctation of the aorta | 21 (3.5%) | |||

| Absence of LMCA | 2 (4.8%) | Absence of LMCA | 16 (2.7%) | |||

| Most common clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities in particular BAV subtypes, n (%) | Type 0 lateral (n = 18) | Type 1 R-L (n = 501) | ||||

| High take-off | 5 (27.8%) | High take-off | 27 (5.4%) | |||

| Coarctation of the aorta | 3 (16.7%) | Paracommissural orifice | 25 (5.0%) | |||

| ASD | 2 (11.1%) | VSD | 22 (4.4%) | |||

| Type 0 A-P (n = 24) | Type 1 R-N (n = 87) | |||||

| VSD Absence of LMCA | 2 (8.3%) 2 (8.3%) | High take-off | 6 (6.9%) | |||

| Coarctation of the aorta | 5 (5.7%) | |||||

| Paracommissural orifice | 4 (4.6%) | |||||

| Type 1 L-N (n = 13) | ||||||

| Only three defects: | ||||||

| ASD | 1 (7.7%) | |||||

| VSD | 1 (7.7%) | |||||

| TGA | 1 (7.7%) | |||||

| Characteristics of the Study Group | ≤40 Years (n = 203) | 41–60 Years (n = 271) | >60 Years (n = 226) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | 60 (29.6%) | 67 (24.7%) | 42 (18.6%) | |||

| Number of clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 98 | 78 | 50 | |||

| Number of defects/person in patients with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 1.63 | 1.16 | 1.19 | |||

| Number of defects/person in the whole group | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.22 | |||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation in the group with clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities | 23.3% | 17.9% | 19.0% | |||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation in the whole group | 17.7% | 15.1% | 11.1% | |||

| the most common clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | High take-off | 21 (10.3%) | Absence of LMCA | 14 (5.2%) | Paracommissural orifice | 11 (4.9%) |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 18 (8.9%) | High take-off | 14 (5.2%) | High take-off | 10 (4.4%) | |

| VSD | 13 (6.4%) | Paracommissural orifice | 11 (4.1%) | VSD | 7 (3.1%) | |

| Paracommissural orifice | 9 (4.4%) | VSD | 10 (3.7%) | ASD | 6 (2.7%) | |

| ASD | 7 (3.4%) | Coarctation of the aorta | 7 (2.6%) | Origin of coronary artery or branch from opposite sinus | 5 (2.2%) | |

| Females ≤ 40 years (n = 54) | Females 41–60 years (n = 85) | Females > 60 years (n = 88) | ||||

| the most common clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | High take-off | 17 (11.4%) | Paracommissural orifice | 5 (5.9%) | Paracommissural orifice | 5 (5.7%) |

| VSD | 11 (7.4%) | High take-off | 3 (3.5%) | High take-off | 3 (3.4%) | |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 9 (6.0%) | VSD | 2 (2.4%) | Origin of coronary artery or branch from opposite sinus | 3 (3.4%) | |

| number of defects/person ratio | 0.69 | 0.28 | 0.24 | |||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation | 16.7% | 11.8% | 17.0% | |||

| Males ≤ 40 years (n = 149) | Males 41–60 years (n = 186) | Males > 60 years (n = 138) | ||||

| Most common clinically relevant cardiovascular abnormalities, n (%) | High take-off | 17 (11.4%) | Absence of LMCA | 12 (6.5%) | High take-off | 7 (5.1%) |

| VSD | 11 (7.4%) | High take-off | 10 (5.4%) | Paracommissural orifice | 6 (4.3%) | |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 9 (6.0%) | VSD | 8 (4.3%) | VSD | 6 (4.3%) | |

| Number of defects/person | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.21 | |||

| % of patients with left-dominant coronary circulation | 18.1% | 16.7% | 7.2% | |||

| Coronary Artery Stenosis Severity (0–4) | BAV (n = 700) | TAV (n = 100) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 0, n (%) | 221 (31.6%) | 42 (42.0%) | 0.037 |

| Category 1, n (%) | 346 (49.4%) | 46 (46.0%) | NS |

| Category 2, n (%) | 12 (1.7%) | 2 (2.0%) | NS |

| Category 3, n (%) | 89 (4.8%) | 8 (8.0%) | NS |

| Category 4, n (%) | 32 (12.7%) | 2 (2.0%) | NS |

| Stenosis > 50% (≥category 2 stenosis severity), n (%) | 143 (20.4%) | 12 (12.0%) | 0.046 |

| Type 0 | Type 1 R-L | Type 1 R-N + 1 L-N | Type 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.46 |

| BAV Type | Type 0 (n = 42) | Type 1 R-L (n = 501) | Type 1 R-N + 1 L-N (n = 100) | Type 1 Total (n = 601) | Type 2 (n = 57) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 46.6 ± 20.0 | 51.4 ± 18.6 | 49.0 ± 19.3 | 51.0 ± 18.7 | 29.8 ± 15.5 |

| Males, % | 71.4% | 68.3% | 60.0% | 66.9% | 71.9% |

| Agatston score (U), mean ± SD | 193.4 ± 590.2 | 158.8 ± 508.9 | 212.7 ± 435.7 | 167.8 ± 497.5 | 4.8 ± 17.7 |

| Classification of Agatston score | |||||

| 0 U | 27 (64.3%) | 276 (55.1%) | 59 (59.0%) | 335 (55.7%) | 49 (86.0%) |

| P1 (1–100 U), n (%) | 6 (14.3%) | 114 (22.8%) | 11 (11.0%) | 125 (20.8%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| P2 (101–300 U), n (%) | 4 (9.5%) | 44 (8.8%) | 8 (8.0%) | 52 (8.7%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| P3 (301–999 U), n (%) | 1 (2.4%) | 50 (10.0%) | 16 (16.0%) | 66 (11.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| P4 (≥1000 U), n (%) | 4 (9.5%) | 17 (3.4%) | 6 (6.0%) | 23 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Agatston score percentiles (U) | |||||

| 25th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75th | 32.5 | 84.0 | 224.5 | 87.0 | 0 |

| 90th | 294.4 | 425.0 | 717.4 | 510.0 | 14.2 |

| 95th | 1230.6 | 805.0 | 1115.7 | 846.0 | 19.2 |

| Age Group | ≤40 Years | 41–60 Years | >60 Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of age group | Females (n = 54) | Males (n = 149) | Total (n = 203) | Females (n = 85) | Males (n = 186) | Total (n = 271) | Females (n = 88) | Males (n = 138) | Total (n = 226) |

| Agatston score (U), mean ± SD | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 4.2 ± 45.7 | 3.1 ± 39.1 | 28.7 ± 116.9 | 127.3 ± 295.7 | 96.4 ± 257.4 | 214.9 ± 446.7 | 460.7 ± 895.5 | 365.0 ± 761.5 |

| Classification of Agatston score | |||||||||

| 0 U, n (%) | 54 (100.0%) | 143 (96.0%) | 197 (97.0%) | 58(68.2%) | 93 (50.0%) | 151(55.7%) | 30 (34.1%) | 33 (23.9%) | 63 (27.9%) |

| P1 (1–100 U), n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (3.6%) | 5 (2.5%) | 21 (24.7%) | 49 (26.3%) | 70 (25.8%) | 27 (30.7%) | 36 (26.1%) | 63 (27.9%) |

| P2 (101–300 U), n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (5.9%) | 19 (10.2%) | 24 (8.9%) | 14 (15.9%) | 19 (13.8%) | 33 (14.6%) |

| P3 (301–999 U), n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 21 (11.3%) | 21 (7.7%) | 12 (13.6%) | 33 (23.9%) | 45 (19.9%) |

| P4 (≥1000 U), n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 4 (2.2%) | 5 (1.8%) | 5 (5.7%) | 17 (12.3%) | 22 (9.7%) |

| Agatston score percentiles (U) | |||||||||

| 25th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 82.5 | 82.5 | 78 |

| 75th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 61 | 44.5 | 547.3 | 508.5 | 408.5 |

| 90th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 378 | 388.5 | 274 | 1116.8 | 1133.4 | 952.5 |

| 95th | 0 | 0 | 0 | 529.8 | 773.5 | 666 | 1581.2 | 1805.6 | 1525.8 |

| Coronary Artery Stenosis Severity (0–4) | Type 0 (n = 42) | Type 1 R-L (n = 501) | Type 1 R-N + 1 L-N (n = 100) | Type 2 (n = 57) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| Category 0, n (%) | 15 (35.7%) | 133 (26.5%) | 34 (34.0%) | 39 (68.4%) | <0.001 |

| Category 1, n (%) | 20 (47.6%) | 276 (55.1%) | 33 (33.0%) | 17 (29.8%) | <0.001 |

| Category 2, n (%) | 3 (7.1%) | 8 (1.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Category 3, n (%) | 2 (4.8%) | 66 (13.2%) | 21 (21.0%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Category 4, n (%) | 2 (4.8%) | 18 (3.6%) | 11 (11.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| Stenosis > 50% (≥category 2 stenosis severity), n (%) | 7 (16.7%) | 92 (18.4%) | 33 (33.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | <0.001 |

| OR [95%CI] | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (0—females; 1—males) | 1.56 [1.01, 2.39] | 0.044 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.07 [1.05, 1.09] | <0.001 |

| Type of BAV (0—other types of BAV; 1—type 1 R-N + 1 L-N) | 2.46 [1.54, 3,94] | <0.001 |

| Calcium score (continuous) | 1.007 [1.006, 1.008] | <0.001 |

| Estimate | SE | t-Test | p-Value | Odds Ratio | −95% CI | +95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b0 | Intercept Log. reg. | −4.926 | 0.586 | 70.48 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.023 |

| b1 | Age | 0.042 | 0.010 | 19.40 | <0.001 | 1.043 | 1.024 | 1.063 |

| b2 | BAV type | 0.997 | 0.333 | 8.97 | 0.003 | 2.709 | 1.411 | 5.201 |

| b3 | Calcium score | 0.006 | 0.001 | 71.46 | <0.001 | 1.006 | 1.004 | 1.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Machowiec, P.; Przybylski, P.; Czekajska-Chehab, E.; Drop, A. Patients with a Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) Diagnosed with ECG-Gated Cardiac Multislice Computed Tomography—Analysis of the Reasons for Referral, Classification of Morphological Phenotypes, Co-Occurring Cardiovascular Abnormalities, and Coronary Artery Stenosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133790

Machowiec P, Przybylski P, Czekajska-Chehab E, Drop A. Patients with a Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) Diagnosed with ECG-Gated Cardiac Multislice Computed Tomography—Analysis of the Reasons for Referral, Classification of Morphological Phenotypes, Co-Occurring Cardiovascular Abnormalities, and Coronary Artery Stenosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133790

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachowiec, Piotr, Piotr Przybylski, Elżbieta Czekajska-Chehab, and Andrzej Drop. 2024. "Patients with a Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) Diagnosed with ECG-Gated Cardiac Multislice Computed Tomography—Analysis of the Reasons for Referral, Classification of Morphological Phenotypes, Co-Occurring Cardiovascular Abnormalities, and Coronary Artery Stenosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133790

APA StyleMachowiec, P., Przybylski, P., Czekajska-Chehab, E., & Drop, A. (2024). Patients with a Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) Diagnosed with ECG-Gated Cardiac Multislice Computed Tomography—Analysis of the Reasons for Referral, Classification of Morphological Phenotypes, Co-Occurring Cardiovascular Abnormalities, and Coronary Artery Stenosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133790