Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for Proximal Humeral Fractures: Primary Treatment vs. Salvage Procedure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

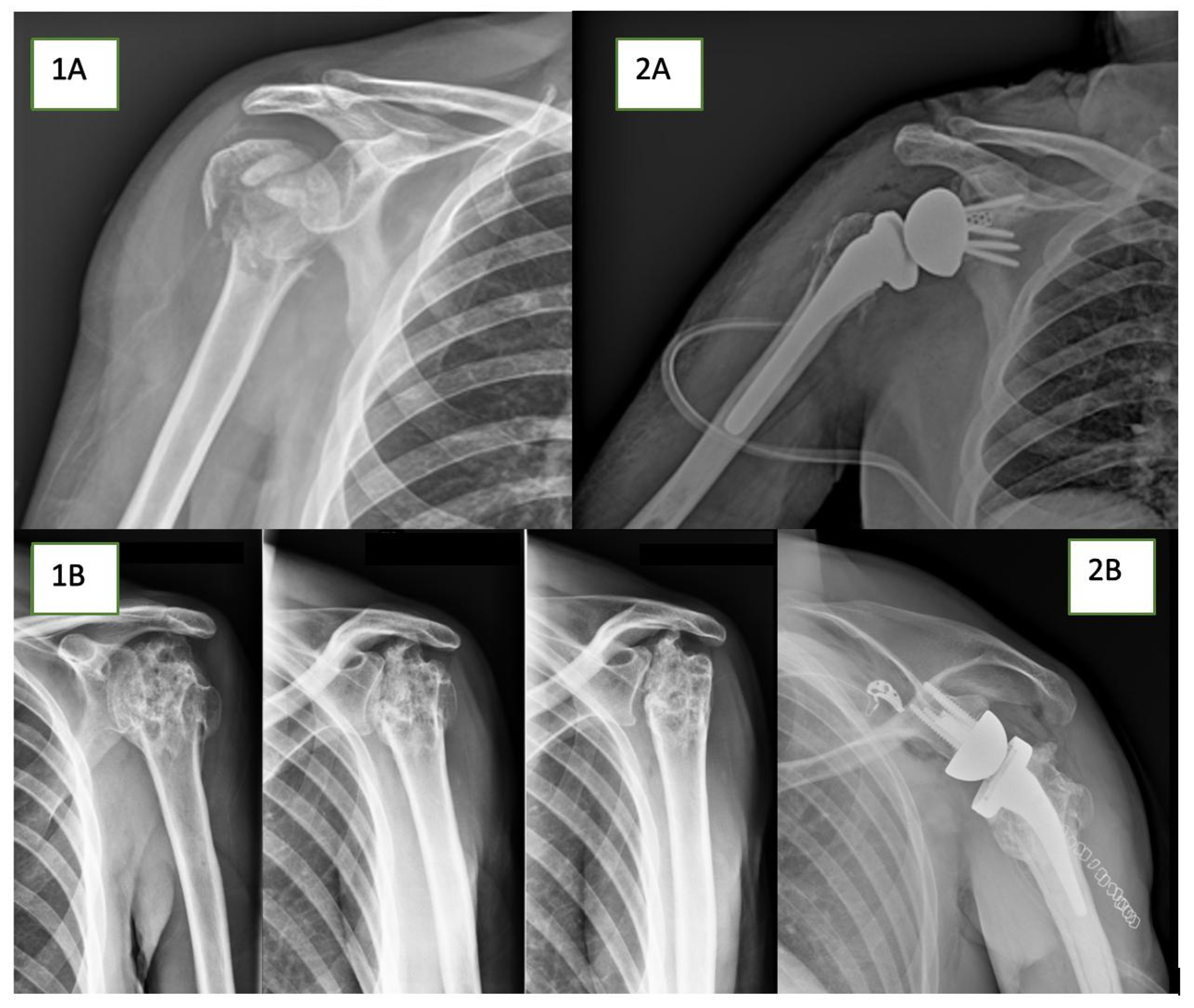

2.5. Surgical Technique

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koeppe, J.; Stolberg-Stolberg, J.; Fischhuber, K.; Iking, J.; Marschall, U.; Raschke, M.J.; Katthagen, J.C. The incidence of proximal humerus fracture—An Analysis of Insurance Data. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2023, 120, 555–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.H.; Wilder, J.H.; Ofa, S.A.; Lee, O.C.; Savoie, F.H., 3rd; O’brien, M.J.; Sherman, W.F. Trending a decade of proximal humerus fracture management in older adults. JSES Int. 2022, 6, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, A.; Handoll, H.; Brealey, S.; Jefferson, L.; Keding, A.; Martin, B.C.; Goodchild, L.; Chuang, L.-H.; Hewitt, C.; Torgerson, D. Surgical vs Nonsurgical Treatment of Adults with Displaced Fractures of the Proximal Humerus: The PROFHER randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015, 313, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, E.; Keough, N.; Glatt, V.; Tetsworth, K. Surgical treatment is not superior to nonoperative treatment for displaced proximal humerus fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 32, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.A.; Kwan, C.C.; Tjong, V.K.; Terry, M.A.; Sheth, U. Primary Versus Salvage Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty for Displaced Proximal Humerus Fractures in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Shoulder Elb. Arthroplast. 2020, 4, 2471549220949731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liu, H.; Xing, R.; Mei, W.; Zhang, L.; Ding, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, P. Effect of intramedullary nail and locking plate in the treatment of proximal humerus fracture: An update systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, G.; Schönthaler, W.; Huf, W.; Komjati, M.; Fialka, C.; Boesmueller, S. Complication rate after operative treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus: Locking plate osteosynthesis versus proximal humeral nail. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 47, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-C.; Li, Y.-L.; Ning, G.-Z.; Wu, Q.; Feng, S.-Q. Treatment of three- and four-part proximal humeral fractures with locking proximal humerus plate. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2013, 23, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.A.; Walch, G.; Pape, G.; Gohlke, F.; Favard, L. Secondary Rotator Cuff Dysfunction Following Total Shoulder Arthroplasty for Primary Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis: Results of a Multicenter Study with More Than Five Years of Follow-up. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2012, 94, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Trojani, C.; Chuinard, C.; Lehuec, J.-C.; Walch, G. Proximal Humerus Fracture Sequelae: Impact of a new radiographic classification on arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006, 442, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmeyer, M.; Schmalzl, J.; Schmidt, E.; Graf, A.; Rentschler, V.; Gerhardt, C.; Lehmann, L.-J. Surgical treatment of fracture sequelae of the proximal humerus according to a pathology-based modification of the Boileau classification results in improved clinical outcome after shoulder arthroplasty. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2024, 34, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugg, C.M.; Coughlan, M.J.; Lansdown, D.A. Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: Biomechanics and Indications. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2019, 12, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.L.; Routman, H. The biomechanics of current reverse shoulder replacement options. Ann. Jt. 2019, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, M.M.; Hussey, S.E.; Mighell, M.A. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty as a salvage procedure after failed internal fixation of fractures of the proximal humerus: Outcomes and complications. Bone Jt. J. 2015, 97-B, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Trojani, C.; Walch, G.; Krishnan, S.G.; Romeo, A.; Sinnerton, R. Shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of the sequelae of fractures of the proximal humerus. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2001, 10, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Gauci, M.-O.; Wagner, E.R.; Clowez, G.; Chaoui, J.; Chelli, M.; Walch, G. The reverse shoulder arthroplasty angle: A new measurement of glenoid inclination for reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2019, 28, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Alta, T.D.; Decroocq, L.; Sirveaux, F.; Clavert, P.; Favard, L.; Chelli, M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for acute fractures in the elderly: Is it worth reattaching the tuberosities? J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2019, 28, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lädermann, A.; Williams, M.D.; Melis, B.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Walch, G. Objective evaluation of lengthening in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2009, 18, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, S.F.; Wagner, E.R.; Houdek, M.T.; Cross, W.W., 3rd; Sánchez-Sotelo, J. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures: Outcomes comparing primary reverse arthroplasty for fracture versus reverse arthroplasty after failed osteosynthesis. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2016, 25, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfuli, B.; King, J.J.; Farmer, K.W.; Struk, A.M.; Wright, T.W. Outcomes of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty as primary versus revision procedure for proximal humerus fractures. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2016, 25, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastia-Forcada, E.; Lizaur-Utrilla, A.; Cebrian-Gomez, R.; Miralles-Muñoz, F.A.; Lopez-Prats, F.A. Outcomes of Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty for Proximal Humeral Fractures: Primary Arthroplasty Versus Secondary Arthroplasty After Failed Proximal Humeral Locking Plate Fixation. J. Orthop. Trauma 2017, 31, e236–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, A.; Sholder, D.; Warrender, W.; Livesey, M.; Williams, G.; Abboud, J.; Namdari, S. Early Versus Late Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for Proximal Humerus Fractures: Does It Matter? Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2017, 5, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Katthagen, J.C.; Hesse, E.; Lill, H.; Schliemann, B.; Ellwein, A.; Raschke, M.J.; Imrecke, J. Outcomes and revision rates of primary vs. secondary reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures. Obere. Extremität. 2020, 15, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, N.A.; Taylor, K.A.; Roche, C.P.; Franovic, S.; Chen, C.; Carofino, B.C.; Flurin, P.-H.; Wright, T.W.; Schoch, B.S.; Zuckerman, J.D.; et al. Acute versus delayed reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures in the elderly: Mid-term outcomes. Semin. Arthroplast. JSES 2020, 30, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.; Yousri, T.; Arealis, G.; Levy, O. The role of reverse shoulder arthroplasty in management of proximal humerus fractures with fracture sequelae: A systematic review of the literature. Orthop. Rev. 2017, 9, 6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary RTSA | Salvage RTSA | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n°) | 42 | 21 | |

| Gender | 0.12 | ||

| Male (n°) | 7 | 8 | |

| Female (n°) | 35 | 13 | |

| Age in years (range) | 75.6 (50−87) | 72.5 (42−85) | 0.09 |

| Surgical site right (n°) | 29 | 11 | |

| Surgical site left (n°) | 13 | 10 | |

| Follow-up in months (Mean ± SD) | 51 ± 23.5 | 49.5 ± 21.8 |

| Primary RTSA | Salvage RTSA | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

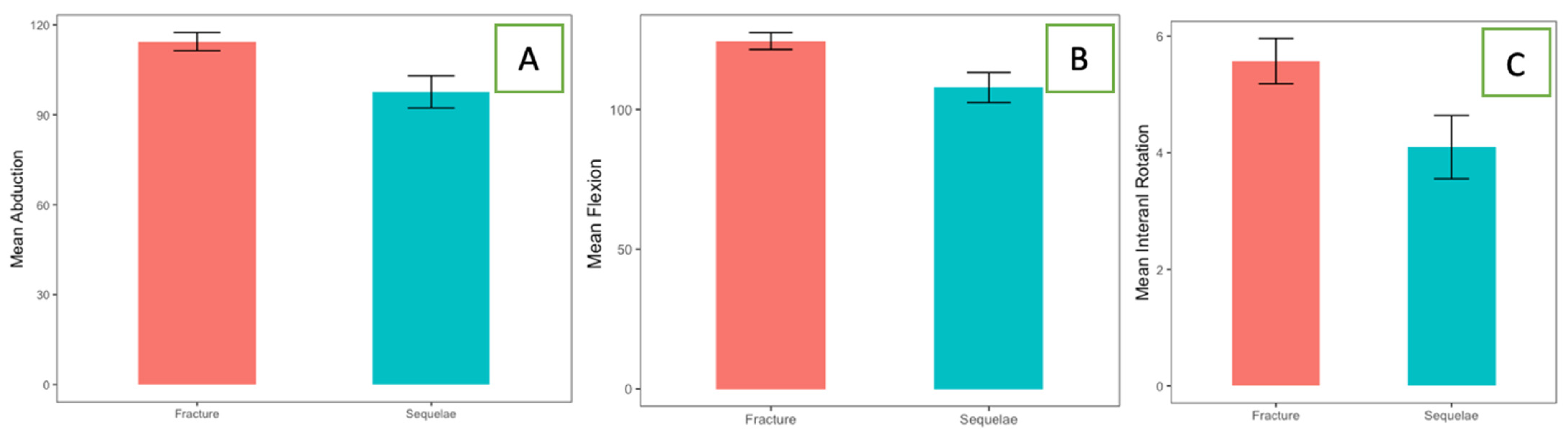

| Abduction (Mean ± SD) | 114.4° ± 19.6 | 97.6° ± 24.6 | 0.007 |

| Anterior forward flexion (Mean ± SD) | 124° ± 19.6 | 107.8° ± 29.4 | 0.02 |

| Intra rotation (Mean ± SD) | 5.6° ± 2.5 | 4.1° ± 2.5 | 0.046 |

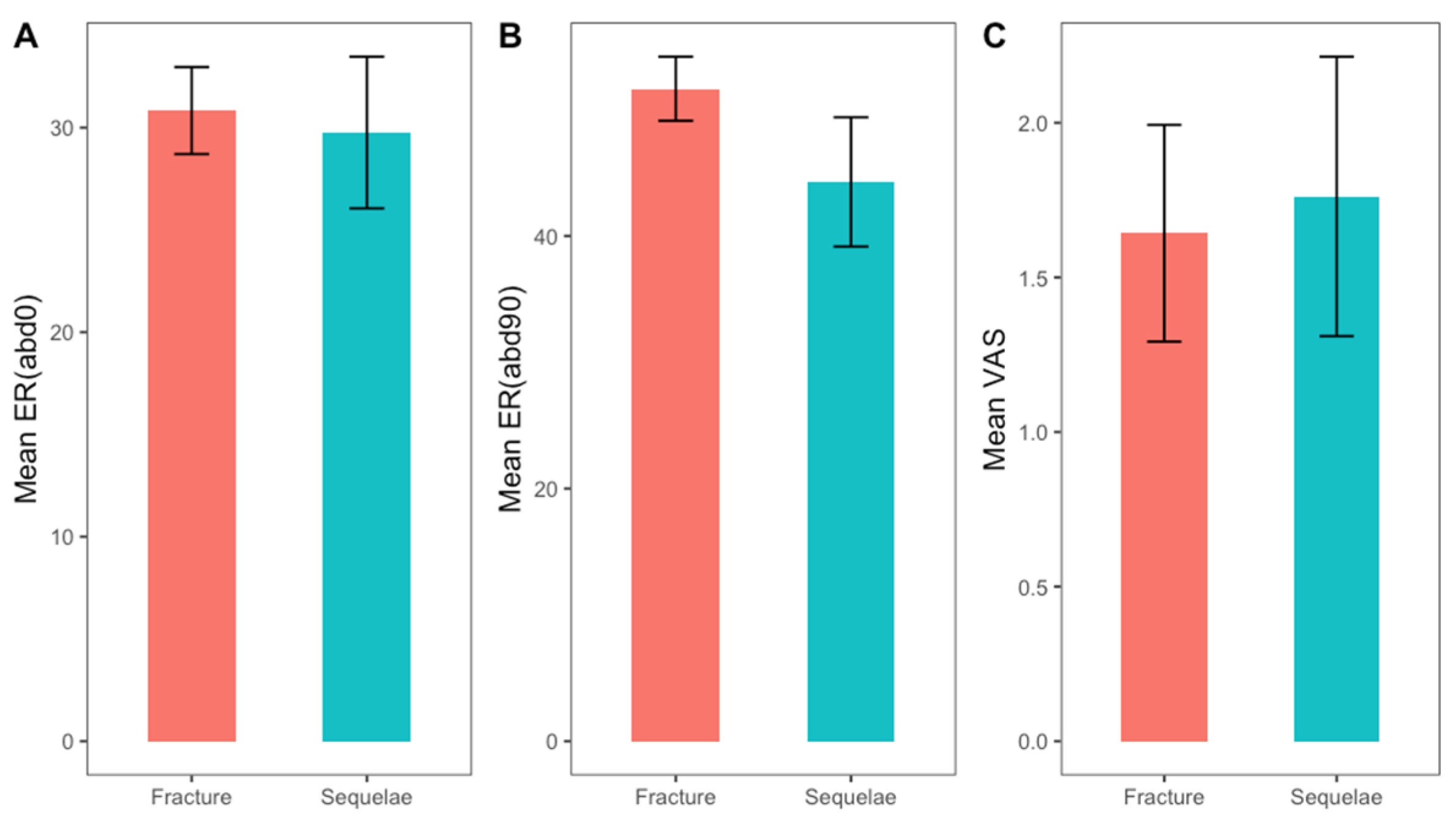

| External rotation (0° abd) (Mean ± SD) | 30.8° ± 13.8 | 29.8° ± 16.6 | 0.7 |

| External rotation (90° abd) (Mean ± SD) | 51.7° ± 16.4 | 44.3° ± 23.5 | 0.15 |

| VAS (Mean ± SD) | 1.6° ± 2.3 | 1.8° ± 2.1 | 0.59 |

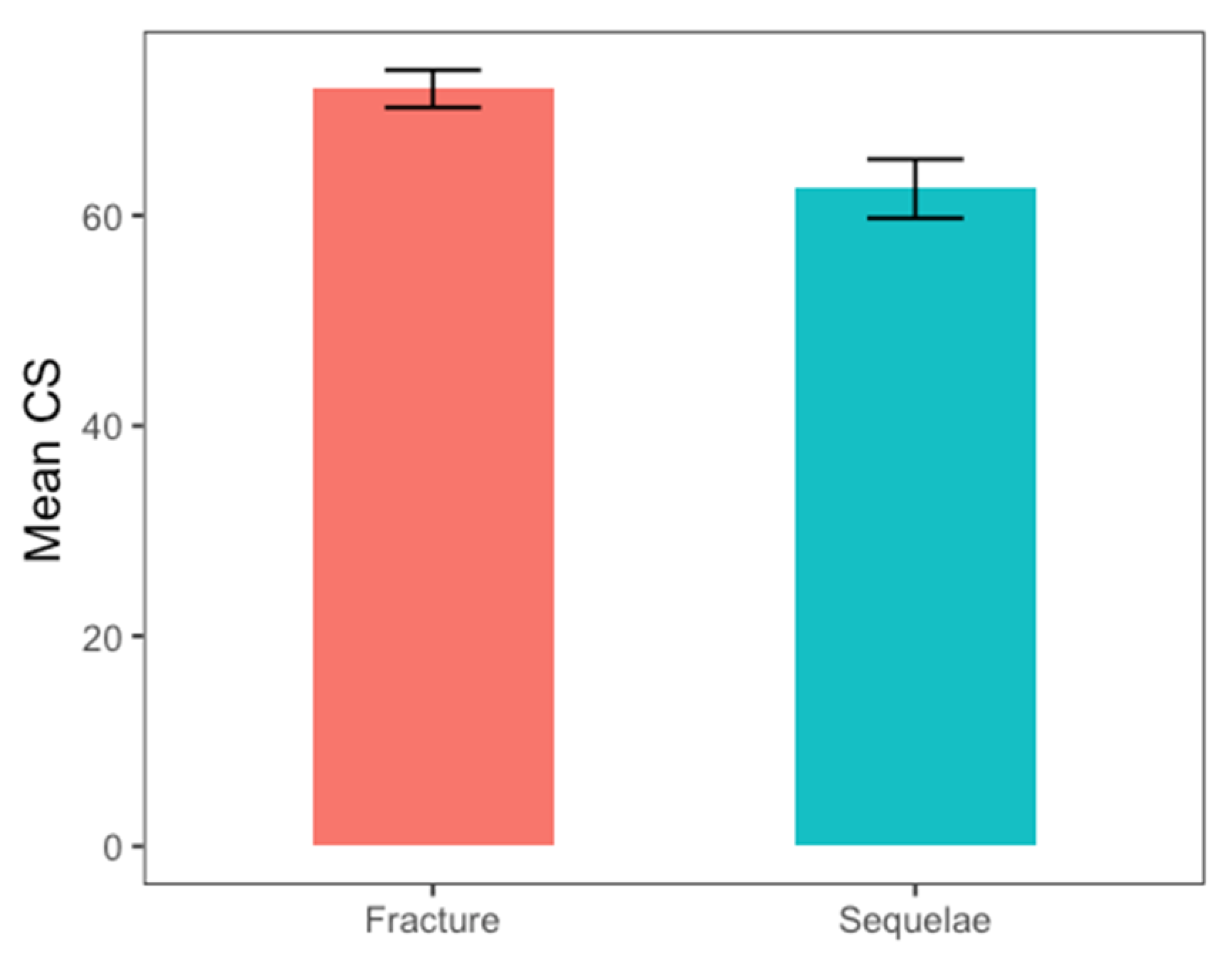

| Constant score (Mean ± SD) | 72.1° ± 11.5 | 62.5° ± 12.9 | 0.009 |

| Primary RTSA | Salvage RTSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Infection (n°) | 1 | - |

| Aseptic glenoid loosening (n°) | 1 | - |

| Axillary nerve palsy (n°) | 1 | 1 |

| Heterotopic ossification (n°) | - | 1 |

| Thrombosis (n°) | - | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caldaria, A.; Saccone, L.; Biagi, N.; Giovannetti de Sanctis, E.; Baldari, A.; Palumbo, A.; Franceschi, F. Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for Proximal Humeral Fractures: Primary Treatment vs. Salvage Procedure. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113063

Caldaria A, Saccone L, Biagi N, Giovannetti de Sanctis E, Baldari A, Palumbo A, Franceschi F. Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for Proximal Humeral Fractures: Primary Treatment vs. Salvage Procedure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(11):3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113063

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaldaria, Antonio, Luca Saccone, Nicolò Biagi, Edoardo Giovannetti de Sanctis, Angelo Baldari, Alessio Palumbo, and Francesco Franceschi. 2024. "Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for Proximal Humeral Fractures: Primary Treatment vs. Salvage Procedure" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 11: 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113063

APA StyleCaldaria, A., Saccone, L., Biagi, N., Giovannetti de Sanctis, E., Baldari, A., Palumbo, A., & Franceschi, F. (2024). Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for Proximal Humeral Fractures: Primary Treatment vs. Salvage Procedure. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(11), 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113063