Abstract

Introduction: The university student population is influenced by multiple factors that affect body awareness. Identifying the body awareness status of students is crucial in creating self-care and emotion management programs to prevent diseases and promote health. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) questionnaire evaluates interoceptive body awareness in eight dimensions through 32 questions. It is one of the few tools that enable a comprehensive assessment of interoceptive body awareness by involving eight dimensions of analysis. Method: The objective of this study is to present the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) to observe to what extent the hypothesized model fits the population of university students in Colombia. A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted with 202 students who met the inclusion criterion of being undergraduate university students. Data were collected in May 2022. Results: A descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic variables of age, gender, city, marital status, discipline, and history of chronic diseases was performed. JASP 0.16.4.0 statistical software was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis. A confirmatory factor analysis was performed based on the proposed eight-factor model of the original MAIA, giving a significant p-value and 95% confidence interval. However, when performing loading factor analysis, a low p-value was found for item 6 of the Not Distracting factor, and for the entire Not Worrying factor. Discussion: A seven-factor model with modifications is proposed. Conclusions: The results of this study confirmed the validity and reliability of the MAIA in the Colombian university student population.

1. Introduction

The mental health of university students has been affected by various social determinants such as high academic load, a sedentary lifestyle, suicidal ideation, depression, early pregnancy, domestic violence, dysfunctional families, poverty, and eating disorders, among others [1]. This has generated interest by researchers in investigating these social determinants in greater depth to promote primary health care programs and generate a culture of care in universities [2].

Some prior studies promote health protective factors such as physical exercise and note that self-esteem is among the switch projective factors for protective factors. One of the pillars of this approach is to ensure adequate body awareness, which implies a conscious mind–body connection linked to internal processes of self-knowledge and self-regulation, confidence in the body, and identification of basic physical sensations such as postural alterations, respiratory and cardiac rhythm, in addition to identifying pain and states of relaxation [3].

Among the theoretical references to the body is corporeality, which refers to the understanding of the body beyond the physical, where an emotional memory produced by the interactions and intersections of the individual with a social context is registered throughout life [4]. Embodiment is related to the perceptual processes that give meaning, representation, and awareness to the body. These sensory and perceptual processes involve body image and body awareness. Body image has neurophysiological, psychological, and behavioral information that shapes the self-image that each person has of his or her own body [5]. Body awareness is the ability to identify the body’s signals to respond in time to situations that may affect health [6]. Body awareness requires information that the body receives from different sources. This information is processed at the neurophysiological level and converted into meanings, known as perceptions, which leave an imprint at the molecular level [7].

When individuals identify bodily sensations and their meaning, they are making themselves conscious of the internal information of their bodies, which is known as interoceptive body awareness. Body awareness can be affected by socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions, and is rarely assessed in university students [4]. Identifying the body awareness status of students is important for creating self-care and emotion management programs. Wellness units are increasingly looking for tools that allow early identification of risks that may affect students’ health conditions, in order to implement promotion and prevention programs [3].

Interoceptive awareness refers to the ability to perceive and understand internal bodily signals, which is important for emotional regulation, decision-making, and stress adaptation. Evaluating interoceptive awareness requires sophisticated techniques and is typically conducted by specialists. Self-report questionnaires are an easy and cost-effective technique that can provide valuable information on how individuals perceive their bodily sensations, identify health issues, and track changes over time. However, self-report questionnaires may have limitations, such as potential for bias, lack of objectivity, and limited ability to measure the physiological aspects of interoceptive awareness. Nonetheless, self-report questionnaires remain a useful and accessible tool for evaluating interoceptive awareness [8,9].

Few tools exist to assess interoceptive body awareness in a multidimensional manner. A study conducted by two universities in the United Kingdom proposes a three-dimensional model that assesses interoceptive accuracy (performance in objective behavioral tests of beat detection, interoceptive sensitivity, and interoceptive awareness [10].

There are other tools to assess body awareness qualitatively, such as BARS; however, to use it, it is necessary to be a basal body awareness therapist [11]. These considerations served as the basis for the creation of the MAIA questionnaire, a multidimensional self-report instrument designed to measure interoceptive body awareness [12]. The MAIA is one of the few instruments that allows a comprehensive assessment of interoceptive body awareness by involving eight dimensions of analysis through 32 items. There is also a 37-item version and another for children aged 7 to 17 years. For this reason, it is being used in different countries and populations. It is currently free to use, and 28 translations have been made available on the website of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine www.osher.ucsf.edu/maia (accesed 3 June 2022).

To date, studies have been conducted on the psychometric characteristics of the MAIA in different linguistic and sociocultural groups. Most studies have maintained the original eight-factor model. Some have found problems with the estimation of the Not Distracted and Not Worried subscales. Items 8 and 10 of the Not Worried subscales have been consistently problematic because of their low factor loadings or loading on other factors [13,14,15]. There are proposed six-factor versions, excluding the dimensions mentioned above, and other proposals that maintain the eight factors with item modifications.

The purpose of this paper is to present the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) to observe to what extent the hypothesized model fits the population of university students in Colombia. Based on the studies taken as the background to our study, confirmatory analysis was applied with the model proposed by Chile, since this version was applied to a Spanish-speaking population; however, the model did not converge with the data from the Colombian student population; therefore, the original version of the MAIA was used.

Factor analyses are useful for researchers who apply instruments because they allow verification of the hypotheses of theoretical constructs, their validity, and reliability for application in specific populations. Confirmatory factor analysis allows the researcher to verify a questionnaire for use in different cultural contexts. The exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the original version of MAIA will be conducted to test the model in the Colombian university student population, replacing the previous analysis [16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Validation Compliance with the Assumptions for the Application of Factor Analysis

The aim of this study is to present the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) to observe to what extent the hypothesized model fits the population of university students in Colombia. The questionnaire was applied to a sample of 232 students, with a final sample of 202. Incomplete questionnaire data were excluded. According to Parra (2019), for sample calculation, 5 to 10 participants per item should be recruited [17]. For the MAIA questionnaire, which has 32 items, the minimum sample should be 160 participants. As a reference for this sample, a study was found that conducted a factor analysis of the psychometric properties of MAIA in a respondent sample of 204 Portuguese university students (52% female; M = 21.3, SD = 3.9 years), where MAIA version 2 was applied [18].

This study was conducted with undergraduate university students from the Escuela Colombiana de Rehabilitación in the city of Bogotá and the Universidad de Manizales in the city of Manizales. A cross-sectional study was used with convenience sampling. The sample consisted of 202 students who met the criterion of being undergraduate university students. Postgraduate students were not included due to the short time they remained in the institutions. The reference age presented in a mean of 21 years, as most of the sample fell within this range.

For the description of the psychometric characteristics of the MAIA questionnaire, both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to assess data factorability. Bartlett’s test of significant sphericity (p < 0.0001) and the KMO index < 0.50 indicate an adequate sample to support factor analysis and the correlation matrix determinant was 2.29 × 10−10. Based on the results obtained, it was possible to perform exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses [19,20]. In the EFA, multiple criteria were used to determine the number of factors to retain, such as the simplicity of the solution (factor loadings 0.30 and no cross-loadings), examination of eigenvalues > 1, and the interpretability of the factor structure [21]. Internal consistency reliability was determined by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Construct validity was estimated following Terwee’s recommendations [22].

2.2. Instruments

All participants completed the Spanish version of the MAIA, using ArcGIS Survey123, a free-to-use Spanish version, which analyzes interoceptive body awareness in 8 categories through 32 questions as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

MAIA categories and questions.

The scale uses a Likert-type measurement scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). It gives a total score for the level of body awareness and a dimensional assessment. For the dimensional assessment, it is important to note that questions 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 are reverse scored [12].

Before answering the questionnaire, the ethical considerations of the study were explained through informed consent, and it was verified that all students who responded had no cognitive difficulties in understanding the questions.

For the present study, we took as background research prior studies on the psychometric characteristics of the 32-item version of the MAIA, in order to conduct our study in a population of Spanish-speaking university students (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prior studies.

The original version of the MAIA validated in a Chilean population was used as a reference for the factorial analysis [14].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted on sociodemographic variables including age, gender, city, marital status, discipline, and history of chronic diseases. For the factor analysis, statistical software JASP 0.16.4.0 and Python were utilized.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Most of the participating students were women (64%), were studying BHASE disciplines (91%), and were aged between 18 and 49 years for 55% were under 21 years of age, with a median age of 21 and a SD o±3.48. 96%. Most were single (65%) and lived in the city of Bogota. Of the participants, 16% reported having a history of chronic diseases. The presence of these chronic diseases was investigated, and it was found that 32% of this sub-group of students reported a history of diseases such as diabetes and respiratory diseases. This information was included in the characterization of students to obtain a general health profile. These histories were not exclusion criteria for administering the questionnaire since MAIA, being a self-report questionnaire, aims to evaluate the perception of interoceptive awareness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographics of university students (n = 202).

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

The calculation of the eigenvalues was carried out, obtaining eight factors corresponding to the values higher than 1.0: 11.4377455, 2.90782465, 2.0218799, 1.54278935, 1.40393595, 1.35838162, 1.13057784, 1.02032593.

For these eigenvalues, the contribution rate of the variation and the cumulative contribution rate of the variation are calculated, obtaining the results shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Contribution rates.

The factor load is analyzed, and no clearly defined factors are obtained, so a varimax rotation is applied; in addition, the questions are separated according to the factors and dimensions proposed by the MAIA questionnaire and the following values are obtained. Based on this analysis, a grouping of questions with high values into a single factor is not identified in the dimensions of Noticing, Not Distracting, Not Worrying and Attention Regulation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factorial load by questions according to MAIA dimensions.

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed based on the proposed factor model of the original MAIA, giving a significant p-value, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

3.4. Factor Loadings

A confirmatory factor analysis of the original MAIA was performed, which resulted in a significant p-value and a 95% confidence interval. However, during the factor loading analysis, a low p-value was found for item 6 of the Not Distracting factor, and for the entire Not Worrying factor. This suggests that these elements may not fit well with the proposed model, and caution should be exercised when interpreting results related to these elements (Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Factor loadings of CFA.

Table 8.

Factor loading.

Finally, a global Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.90 and an omega coefficient (Ω = 0.96) were found.

The study conducted among a Chilean student population is the closest to the Colombian population; however, when applying the adjusted six-factor model proposed in the Chilean study, it did not converge with the data from the Colombian student population. The factorial analysis performed in this study used the original version of MAIA translated into Spanish in the validation study conducted by Chile, where they found significant factor loadings for the eight factors and the best goodness-of-fit statistics with 30 items [14].

Overall, the results of the present study suggest that the version of the MAIA used is a useful and reliable tool for measuring interoceptive awareness in the studied population. However, further studies are needed to confirm the validity and reliability of the MAIA in different populations and transcultural contexts, as well as to explore possible adjustments to the proposed model.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study is to present the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) Spanish version to observe to what extent the hypothesized model fits the population of university students in Colombia. The questionnaire was applied to a sample of 202 students. Among this sample, a global Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.90 was found. Other studies report a Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.90 was found in 202 students aged between 18 and 32 years. This result is similar to those of the MAIA in the German version, the Spanish version, and the Italian version [14,21,23]. The results reveal an internal consistency through the omega coefficient (Ω = 0.95), which is considered good. Among prior studies carried out using the MAIA, application of the omega coefficient is not found; however, this sample was used in similar studies supporting their findings with the global Cronbach’s alpha [27,28,29].

For the EFA of the present study, an eight-dimensional factorial structure was contemplated. Because no clearly defined factors were obtained, a varimax rotation was applied; additionally, the questions were separated according to the factors and dimensions proposed by the MAIA questionnaire. It was found that there was no group of questions with high values in a single factor in the dimensions relating to noticing, non-restlessness and regulation of attention. This can be coindexed with the study conducted in Chile with a sample of 470 participants aged between 18 and 70 years; the eight-factor EFA results found a model with loads greater than or equal to 0.30, where seven of the eight factors comprised three or more. The eight-factor model achieved the highest quality and was used to perform the AFC. As an analytical strategy, they used the ML method with Spanish Promax rotation [14].

A translation and validation study in Malaysia with 815 Malaysians (403 females) suggested a 19-item, three-factor structure. The confirmatory factor analysis indicated that both the three-factor and eight-factor models exhibited complete strict invariance between the sexes. Overall, the three-dimensional Malaysian MAIA proved to be internally consistent and invariant between the sexes, but further tests of construct and convergent validity are required [27]. A cross-sectional study involving 268 Japanese individuals proposed a six-factor structure that proved useful for assessing interoceptive awareness in the Japanese population [26]. In the confirmatory factorial analysis, the Japanese six-factor model showed a good fit to the original model [30]. The results suggest the need to make minor modifications, such as the elimination or addition of items to the original eight-factor model, to validate the MAIA scale in transcultural contexts.

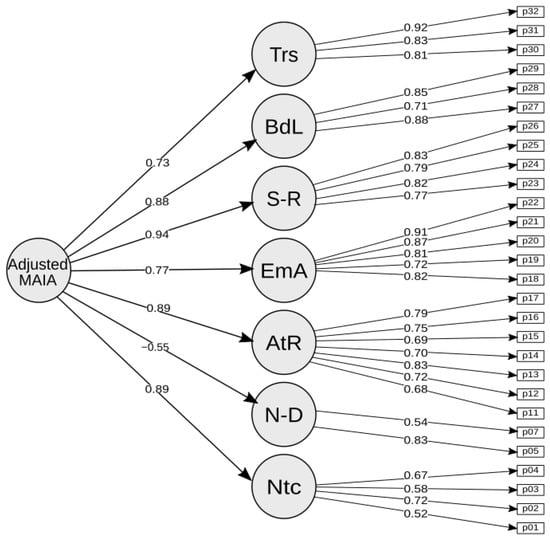

We propose a seven-factor model with modifications, removing the Not Worrying factor, as it has a p-value of 0.0405, and item 6 of the Not Distracting factor, as it has a p-value of 0.087. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed with this proposal, giving the following results (Table 9).

Table 9.

Adjusted confirmatory factor analysis.

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed based on the proposed factor model of the original MAIA, giving a significant p-value and a 95% confidence interval. However, the factorial loading analysis found a low p-value for item 6 of the Not Distracting factor, and for the entire Not Worrying factor (Table 10 and Figure 1).

Table 10.

Adjusted factor loading.

Figure 1.

Proposed seven-factor MAIA.

This study showed that the Spanish version of the 32-item MAIA applied to the Colombian population has acceptable psychometric properties. The adjusted exploratory factor analysis suggested an eight-factor model; however, it is suggested to verify the dimension of Noticing, Not Worrying, and Attention Regulation. Some studies suggest models with six or seven factors by discarding some items [25].

5. Conclusions

This study showed that the Spanish version of the 32-item MAIA applied to Colombian university students has adequate psychometric properties in terms of validity and reliability.

The CFA suggested a seven-factor model discarding the entire Not Worrying factor and item 6 of the Not Distracting factor.

The MAIA shows good overall internal consistency reliability and is a suitable instrument to assess interoceptive awareness in the population of university students with different sociodemographic characteristics.

It is important that the questionnaire is completed by university students who understand the questions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M.-H.; methodology, N.G.-J.; software, G.B.-J.; validation, L.C.-O.; formal analysis, N.G.-J.; investigation, L.C.-P., R.J.-V. and I.S.-A.; resources, L.C.-P.; data curation, S.C. and I.S.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.-H.; writing—review and editing, M.C.S.-S. and O.M-H.; visualization, J.P.; supervision, J.C.-G., J.P. and R.J.-V.; project administration, J.C.-G.; funding acquisition, R.J.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Colombian School of Rehabilitation and for the University of La Rioja.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were carried out under the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of Principles. The ethics committee of the Colombian School of Rehabilitation received the endorsement ECR-CI-INV-121-2021 and the and CBE07 Act of the University of Manizales. All students signed an informed consent explaining the research, its implications, and the security of personal data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Generated Statement: No potentially identifiable human images or data is presented in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chau, C.; Vilela, P. Determinants of mental health in university students from Lima and Huánuco. Rev. De Psicol. 2017, 35, 387–422. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/psico/v35n2/a01v35n2.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Becerra Heraud, S. Healthy universities: A commitment to integral student training. Rev. De Psicol. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Idrugo Jave, H.A.; Sánchez Cabrejos, W.M. Mental health in medical students. Investig. En Educ. Médica 2020, 3, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Bergel Petit, E. Mindfulness, body awareness, and academic performance in university students: A pilot study. Sci. Med. Data 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Jiménez, R.M.; Velasco-Quintana, P.J.; Terrón-López, M.J. Building healthy universities: Body awareness and personal well-being. Rev. Iberoam. De Educ. 2014, 66, 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado Herrera, D.R. Corporeality and motricity. A way of looking at body knowledge. Lúdica Pedagógica 2007, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M.P.; Smolak, L. Paradigm clash in the field of eating disorders: A critical examination of the biopsychiatric model from a sociocultural perspective. Adv. Eat. Disord. 2013, 2, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.J.; Acree, M.; Bartmess, E.; Stewart, A. The multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, B.M.; Pollatos, O. Attenuated interoceptive sensitivity in overweight and obese individuals. Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Seth, A.K.; Barrett, A.B.; Suzuki, K.; Critchley, H.D. Knowing your own heart: Distinguishing interoceptive accuracy from interoceptive awareness. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 104, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjaerven, L.H.; Gard, G.; Sundal, M.A.; Strand, L.I. Reliability, and validity of the Body Awareness Rating Scale (BARS), an observational assessment tool of movement quality. Eur. J. Physiother. 2015, 17, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.; Bartmess, E.; Acree, M.; Gopisetty, V.; Stewart, A. P05.61. The multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness (MAIA). BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, P421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calì, G.; Ambrosini, E.; Picconi, L.; Mehling, W.E.; Committeri, G. Investigating the relationship between interoceptive accuracy, interoceptive awareness, and emotional susceptibility. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Moguillansky, C.; Reyes-Reyes, A. Psychometric properties of the multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness (MAIA) in a Chilean population. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William Li, H.C.; Chung, O.K.J.; Ho, K.Y. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children: Psychometric testing of the Chinese version. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2582–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J. Confirmatory factor analysis in the study of structure and stability of assessment instruments: An example with the Self-esteem Questionnaire CA-14. Psychosoc. Interv. 2010, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, F. Estadística y Machine Learning Con R [Internet]. Econometria. Wordpress. 2019. Available online: https://bookdown.org/content/2274/portada.html (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Machorrinho, J.; Veiga, G.; Fernandes, J.; Mehling, W.; Marmeleira, J. Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness: Psychometric Properties of the Portuguese Version. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2018, 126, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.R.D.; Bonafé, F.S.S.; Marôco, J.; Maloa, B.F.S.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Abbreviated version in Portuguese-speaking adults from three different countries. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2018, 40, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.S.; de Maria, M.; Barbaranelli, C.; Vellone, E.; Matarese, M.; Ausili, D.; Rejane, R.E.; Osokpo, O.H.; Riegel, B. Cross-cultural applicability of the Self-Care Self-Efficacy Scale in a multi-national study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 77, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, B. A First Course in Factor Analysis. Technometrics 1993, 35, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, M.; Ghorbani, N.; Hatami, J.; Gholamali, L.M. Validity and Reliability of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) in Iranian students. J. Sabzevar Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Baranauskas, M.; Grabauskaite, A.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. Psychometric characteristics of Lithuanian version of Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA LT). Neurol. Semin. 2016, 20, 202–206. Available online: https://osher.ucsf.edu/sites/osher.ucsf.edu/files/inlinefiles/MAIA_Lithuanian_Validation.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Fujino, H. Further validation of the Japanese version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M.; Mehling, W.E.; Hautzinger, M.; Herbert, B.M. Investigating Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness in a Japanese population: Validation of the Japanese MAIA-J. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.; Barron, D.; Aspell, J.E.; Toh, E.K.L.; Zahari, H.S.; Khatib, N.A.M.; Swami, V. Translation and validation of a Bahasa Malaysia (Malay) version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, D. Further Insights into the German Version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferentzi, E.; Olaru, G.; Geiger, M.; Vig, L.; Köteles, F.; Wilhelm, O. Examining the Factor Structure and Validity of the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness. J. Personal. Assess. 2020, 103, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiire, S.; Matsumoto, N. The Further Validation of the Japanese Version of Short UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (SUPPS-P-J). Jpn. J. Personal. 2022, 31, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).