Continuing Challenges in the Definitive Diagnosis of Cushing’s Disease: A Structured Review Focusing on Molecular Imaging and a Proposal for Diagnostic Work-Up

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis and Synthesis

2.4. Illustrative Patient Cases

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Imaging in Cushing’s Disease (See Also Table 1)

| Ref. | Author | Year | Tracer | Imaging Modality | Population | MRI Findings | Results | Conclusion Authors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age | Sex * | De Novo/Recurrent | Negative or Inconclusive | ≤6 mm | 7–9 mm | ≥10 mm | |||||||

| [19] | Tang et al. (Erasme Hospital, Belgium) | 2006 | 11C-Met (555 Mbq) | PET + MRI (1.5T SE, gadolinium-based) | 8 ** | X | X | 0/8 | 7/8 (88%) | 1/8 (13%) | Population: pituitary adenoma with biochemical evidence of active residual/regrowth ≥ 3 mnd post-TSS Adenoma detection: - MRI = 1/8 (13%) 1/1 correct localization; 7/8 not able to differentiate residual adenoma from scar formation - 11C-Met PET = 8/8 (100%), 8/8 correct localization Histological confirmation: unknown Outcome: - 6/8 GKRS: 4/6 no medical Tx needed after GKRS, 2/6 ketoconazole - 1/8 s TSS - 1/8 observation | 11C-Met -PET is a sensitive technique complementary to MRI for the detection of residual or recurrent pituitary adenoma. The metabolic data provides decisive complementary information for dosimetry planning in GKRS (particularly ACTH-secreting pituitary adenoma). It should gain a place in the efficient management of these tumors. | ||

| [20] | Alzahrani et al. (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Saudi Arabia) | 2009 | 18F-FDG (370 Mbq) | PET–CT + MRI (1.5T SE, gadolinium-based) | 12 | 40 (31–51) | 33% | 7/5 | 4/12 (33%) | 2/12 (17%) | 3/12 (25%) | 3/12 (25%) | Population: proven CD on biochemical (stimulation) tests, radiological and/or histopathological findings Adenoma detection: - MRI = + in 8/12 (67%), − in 4/12 (33%); of which 1/4 + on PET–CT - 18F-FDG PET–CT = + in 7/12 (58%) and - in 5/12 (42%) of which 2/5 (40%) + on MRI Not histologically proven (n = 2): negative on MRI and 18F-FDG PET–CT, IPSS: CD, 1/2 clear lateralization. De novo (n = 7): - MRI = + in 4/7 (57%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT = + in 3/7 (43%) but all seen on MRI Recurrent (n = 5) - MRI = + in 4/5 (80%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT = + in 4/5 (80%) of which 1 not seen on MRI 18F-FDG PET–CT to size negative MRI = 1/4 (25%) ≤6 mm = 2/2 (100%) 6–9 mm = 2/3 (67%) ≥10 mm = 2/3 (67%) Histological confirmation: yes in n = 10, no in n = 2 (IPSS) Outcome after TSS: - negative MRI: 1/4 remission, 2/4 persistent, 1/4 controlled with Tx - ≤6 mm: 2/2 persistent - 6–9 mm: 2/3 persistent, 1/3 remission - ≥10 mm: 2/3 remission, 1/3 persistent Without histological confirmation: 1/2 persistent, 1/2 controlled with Tx. De novo: 3/7 remission, 3/7 persistent, 1/7 controlled with Tx Recurrent: 4/5 persistent, 1/5 remission | 18F-FDG PET–CT is positive in ± 60% of CD cases. Although the majority of cases with positive 18F-FDG PET–CT had positive MRI, PET–CT may detect some cases with negative MRI and thus provides important diagnostic information. If these findings are confirmed in larger studies, PET–CT might become an important diagnostic technique, especially when MRI is negative or if IPSS is not available or inconclusive |

| [21] | Ikeda et al. (Southern Tohuku General Hospital, Japan) | 2010 | 18F-FDG (185 Mbq) + 11C-Met (280–450 Mbq) FDG 1 h after Met injection | PET-MRI (12 by 3.0T) + MRI (19 by 3.0T, 16 by 1.5T; SE and gadolinium-based) | 35 | 46.5 (11–76) | 29% | 35/0 | 10/30 (33%) *** | 30/35 (86%) of which 18/30 overt (60%) 12/30 preclinical (40%) | 5/35 (14%) of which 2/5 overt (40%) 3/5 preclinical (60%) | Population: histologically proven Cushing’s adenoma after TSS, overt (n = 20) and preclinical (n = 15) Adenoma detection: - MRI microadenoma (n = 30): - 1.5T = + in 8/14 (57%) of which preclinical: + in 2/5, overt: + in 6/9 - 3.0T = + in 4/16 (25%) of which preclinical: + in 1/7, overt: + in 3/9 12/30 (40%): good correlation to surgical findings: 10 false-, 6 false+ and 3 double pituitary adenoma - 11C-Met-PET/MRI 3.0T = + in 11/11 (100%) and 100% accuracy - 18F-FDG–PET/MRI 3.0T = + in 8/12 (67%) To size - microadenoma: 11C-Met-PET/MRI: + in 8/8 18F-FDG–PET/MRI: + in 6/8 - macroadenoma: 11C-Met-PET/MRI: + in 3/3 18F-FDG–PET/MRI: + in 2/3 To stage - preclinical: 11C-Met-PET/MRI: + in 5/5 18F-FDG–PET/MRI: + in 2/5 - overt: 11C-Met-PET/MRI: + in 6/6 18F-FDG–PET/MRI: + in 6/7 Histological confirmation: yes Outcome: unknown | 11C-Met-PET/3.0T MRI provides higher sensitivity for determining the location and delineation of Cushing’s adenoma than other neuroradiological imaging techniques ([dynamic] MRI and CT). A pituitary adenoma is better delineated on 11C-Met -PET than 18F-FDG–PET. No difference in SUVmax of 11C-Met and 18F-FDG -PET between overt and preclinical CD in terms of glucose and amino acid metabolism within adenoma; therefore, 11C-Met-PET/MR imaging is useful in detecting early-stage Cushing’s adenoma. If there is PET-positive imaging around the pituitary region and CD is doubted endocrinologically, then we believe that surgery is justified, implying that IPSS can be omitted. | |

| [22] | Seok et al. (Yonsei University College of Medicine, Korea), Prospective | 2013 | 18F-FDG (259–333 Mbq) | PET + MRI (1.5T SE, gadolinium contrast) | 2 ** | 17 + 58 | 50% | 2/0 | 1/2 (50%) | 0 | 0 | 1/2 (50%) | Population: 32 patients investigated for pituitary lesions Adenoma detection: - MRI: + in 1/2 (50%; macroadenoma) - 18F-FDG–PET: + in 1/2 (50; macroadenoma; same as MRI) Histological confirmation: unknown Outcome: unknown | 18F-FDG–PETis an ancillary tool for detecting and differentiating various pituitary lesions in certain circumstances. Further PET studies determining the right threshold of SUVmax or conjugating various tracer molecules will be helpful. |

| [23] | Chittiboina et al. (National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, USA) Prospective | 2015 | 18F-FDG (≥ 18 years = 370 Mbq and <18 years = 2.96 Mbq/kg) | hrPET + MRI (1.5T SE + SPGR, gadolinium contrast) | 10 | 30.8 ± 19.3 (11–59) | 30% | 9/1 | SE: 6/10 (60%), SPGR: 3/10 (30%) | 7/10 (70%) (max diameter of adenoma at surgery) | 0/10 | 3/10 (30%) (max diameter of adenoma at surgery) | Population: consecutive patients with CD (biochemical tests, MRI—pituitary, and/or IPSS) Adenoma detection: - MRI SE = + in 4/10 (40%) SPGR = + in 7/10 (70%), - 18F-FDG hrPET = + in 4/10 (40%) 3 detected on SPGR but not on PET 1 detected on SE but not on PET 2 detected on PET but not on SE Location corresponded with the surgical location in all positive MRI and hrPET. De novo (n = 9) MRI SE: + in 4/9 MRI SPGR: + in 6/9 18F-FDG hrPET: + in 4/9 Recurrent (n = 1): MRI SE: + in 0/1 MRI SPGR: + 1/1 18F-FDG hrPET: + in 0/1 To size: - negative SPGR: 0/3 + on PET - negative SE: 2/6 + on PET - ≤6 mm: 2/7 - on all; 2/7 + on SE + SPGR, - on PET; 2/7 + on PET + SPGR, - on SE 1/7 + on SPGR, - on PET + SE - ≥10 mm: 2/3 + on all 3, 1/3 - on all 3 Histological confirmation: yes Outcome: 10/10 (100%) biochemical remission after surgery. | While 18F-FDG hrPET can detect small functioning corticotropinomas (3 mm) and is more sensitive than SE MRI, SPGR MRI is even more sensitive. High midnight ACTH levels and an attenuated response to CRH stimulation can predict 18F-FDG hrPET-positive adenomas in CD. |

| [24] | Boyle et al. (National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, USA) Prospective | 2019 | 18F-FDG (≥18 years = 370 Mbq and <18 years= 2.96 Mbq/kg) with and without CRH stimulation (1 mcg/kg): 0, 2, or 4 h prior to PET | hrPET + MRI (SE + SPGR, gadolinium contrast) | 27 | 34.9 ± 16.8 (10–61) | 26% | 23/4 | 9/27 (33%) of which 5/9 negative (-) and 4/9 questionable (?) | 7/27 (26%) | 3/27 (11%) | 8/27 (30%) | Population: subjects with likely diagnosis of CD (based on biochemical data, IPSS when incongruent or MRI negative/lesions <6 mm) Adenoma detection: (2 reviewers: neuroradiologists) - MRI = + in 18/27 (67%), −/? in 9/27 of which 2/5+ on PET [1 after CRH] - 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = ≥1 reviewer + in: 12/27 (44%) both reviewers: + in 8/27 (30%) - in 15/27(56%): of which 8 + on MRI - 18F-FDG hrPET PET with CRH = ≥ 1 reviewer + in: 15/27 (56%) both reviewers: + in 14/27 (52%) - in 12/27(44%): of which 5 + on MRI No false+ De novo (n = 23) - MRI = + in 17/23 (74%) - 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = ≥1 reviewer + in: 11/23 (48%) both reviewers: + in 7/23 (30%) - 18F-FDG hrPET with CRH = ≥1 reviewer + in: 14/23 (61%) both reviewers: + in 11/23 (48%) Recurrent (n = 4) - MRI = + in 1/4 (25%), −/? in 3/4 - 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = ≥1 reviewer + in: 1/4 (25%) both reviewers: + in 1/4 (25%) same + as on MRI - 18F-FDG hrPET with CRH = ≥1 reviewer + in: 2/4 (50%) both reviewers: + in 2/4 (50%) same + as on MRI and 1 - MRI To size: - inconclusive (n = 9): 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = + in 1/9 18F-FDG hrPET with CRH = + in 2/9 - <6 mm (n = 7): 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = + in 3/7 18F-FDG hrPET with CRH = + in 4/7 - 7–9 mm (n = 3) 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = + in 3/3 18F-FDG hrPET with CRH = + in 3/3 - ≥10 mm (n = 8) 18F-FDG hrPET no CRH = + in 5/8 18F-FDG hrPET with CRH = + in 7/8 Histological confirmation: yes Outcome: unknown | CRH stimulation may lead to increased 18F-FDG uptake and an increased rate of detection of corticotropinomas in CD. These results also suggest that some MRI-invisible adenomas may be detectable by CRH-stimulated 18F-FDG–PET imaging. These findings invite further prospective evaluation; if validated, CRH-stimulated PET imaging could complement MRI to improve the presurgical visualization of ACTH-secreting microadenomas. |

| [25] | Koulouri et al. (Wellcome-MRC Institute of Metabolic Science) | 2015 | 11C-Met (300–400 Mbq) | PET–CT + MRI (1.5T SE + SPGR, gadolinium contrast) | 18 | 43 (17–77) | 20% | 10/8 | SPGR: 3/18 (17%) SE: 7/18 (39%) | X (de novo: 6/10 possible microadenoma on conventional MRI SE) | Population: ACTH-dependent CS, de novo and residual/recurrent (all TSS + 2 also previous Rx) Adenoma detection: - De novo: MRI SE = + in 6/10 (60%) MRI SPGR = + in 10/10 (100%) 11C-Met PET–CT: + in 7/10 (70%); all 7 co-localized with adenoma on SPGR − in 3/10 (30%) - Recurrent: MRI SE/SPGR: + in 5/8 11C-Met PET–CT: + in 5/8 (63%); all 5 co-localized with adenoma on MRI − in 3/8 (38%), all 3 also - on MRI Histological confirmation.: yes Outcome after TSS: De novo: described for 6/10: + on PET: 3/7 remission, 4/7 not given − on PET:1/3 remission, 2/3 persistent Recurrent: described for 2/8: 2/2 in remission | 11C-Met PET/MRI may help inform decision making in: (i) de novo CD and suspected lesion on MRI (SE, dynamic, or SPGR) to confirm functionality within the visualized lesion; (ii) after noncurative TSS or with the recurrent disease when further surgery or Rx is considered: to distinguish the disease from post-treatment change/scar tissue. We speculate that a multimodel pituitary imaging approach using SE and/or SPGR pituitary MRI and 11C-Met PET–CT could be adopted for ‘difficult’ pituitary Cushing’s cases in order to maximize the chance of adenoma detection and localization. | ||

| [26] | Feng et al. (The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, China) | 2016 | 11C-Met (280–450 Mbq) + 18F-FDG (370 Mbq) Preformed on separate days within 1 week | PET–CT + MRI | 15 ** | 38.3 ± 9.19 (28–55) | 47% | 11/4 | 2/15 (13%) *** (2 equivocal MRI: 4 + 5 mm) | 6/15 (40%) | 5/15 (33%) | 4/15 (27%) | Population: adenoma location in functional PA Adenoma detection: - MRI: + in 13/15 (87%), equivocal in 2/15 (13%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 10/15 (67%), in 5/15 (33%), no false+, 100% specificity (all concordant) - 11C-Met PET–CT: + in 15/15 (100%), of which 1/15 false +, specificity: 93% De novo - MRI: + in 10/11, - in 1/11: + on both FDG and Met, but disconcordant (5 mm) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 9/11 (82%), - in 2/11: 4 and 5 mm - 11C-Met PET–CT: + in 11/11 (1 false +) Recurrent - MRI: + in 3/4, − in 1/4: + on both FDG and Met (4 mm) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 1/4, - in 3/4 - 11C-Met PET–CT: + in 4/4 To size: - equivocal (n = 2): 2/2 + on FDG and PET, but 1/2 disconcordant: lesion of FDG was a true lesion during surgery - <6 mm (n = 6): 18F-FDG + in 3/6 11C-Met + in 6/6 of which 1 false + - 6–9 mm (n = 5): 18F-FDG + in 4/5 11C-Met + in 5/5 - ≥10 mm (n = 4): 18F-FDG + in 3/4 11C-Met + in 4/4 Histological confirmation: yes Outcome: unknown | The positive rate of 11C-Met PET–CT in ACTH-secreting pituitary adenoma is as high as 100% and a promising, noninvasive method that could even replace IPSS under specific circumstances. The sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET–CT is unsatisfactory. Functional pituitary adenoma in general: PET–CT may be useful to detect tumors in patients with equivocal MRI results. Met–PET can provide valuable diagnostic information when 18F-FDG–PET yields negative results (not vice versa). |

| [27] | Wang et al. (The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, China) Prospective | 2019 | 13N-ammonia (444–592 Mbq) + 18F-FDG (370 Mbq) FDG 2 h after ammonia | PET–CT + MRI (3.0T SE, gadolinium contrast) | 10 ** | 38.4 ± 9.55 (28–55) | 40% | 8/2 | 1/10 (10%) *** | 3/10 (30%) | 2/10 (20%) | 5/10 (50%) | Population: = position of pituitary tissue in patients with pituitary adenoma Adenoma detection: - MRI = + in 9/10 (90%), also correct localization − in 1/10 (10%); de novo, 5 mm + on 18F-FDG but - on 13N-ammonia - 13N-ammonia PET–CT: + in 9/10 (90%), also correct localization - in 1/10 (10%); same as - on MRI All positives concurrent L/R position. Histological confirmation.: yes Outcome: unknown | Pituitary adenoma in general: 13N-ammonia PET–CT imaging is a sensitive means for locating and distinguishing pituitary tissue from PAs, particularly those with tumor maximum diameter <2 cm. It is potentially valuable in the detection of pituitary tissue in pituitary adenoma. |

| [28] | Zhou et al. (Ruijin Hospital, China) | 2019 | 18F-FDG (4.44–5.55 Mbq/kg) | PET–CT + MRI | 11 | 44.8 ± 14.7 (17–74) | 34% | 11/0 | 4/11 (36%) | 4/11 (36%) | 3/11 (27%) | Population: patients who underwent whole-body 18F-FDG PET–CT to identify ACTH-dependent CS source Adenoma detection: - MRI: + in 7/11 (64%), specificity: 72% - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + 4/11 (36%, all also seen on MRI), specificity: 50% To size: - inconclusive: 18F-FDG + in 0/4 - microadenoma: 18F-FDG + in 3/4 - macroadenoma: 18F-FDG + in 1/3 Histological confirmation: yes Outcome: unknown | 18F-FDG PET–CT plays a role in localizing the site for EAS (especially mediastinal, pancreatic, and nasal endocrine tumors), although it plays a limited role in CD | |

| [29] | Walia et al. (Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, India) Prospective | 2020 | 68Ga-DOTA-CRH (111–185 Mbq) | PET–CT + MRI (3.0T SPGR, gadolinium contrast) | 24 | 37.4 (13–64) | 37% | 24/0 | 4/24 (17%) *** | 10/24 (42%) | 7/24 (29%) | 7/24 (29%) | Population: ACTH-dependent CS Adenoma detection: - MRI: + in 20/24 (83%), − in 4/24 (17%; of which 1 empty sella, 2 normal and 1 post-op changes > CRH PET–CT correctly delineated lesions) - 68Ga-DOTA-CRH PET–CT = + in 24/24 (100%), lateralization also 100% Histological confirmation.: yes Outcome: PET information used for intraoperative navigation: biochemical remission in 12/17 (71%) of micro- and 4/7 (57%) macroadenoma | 68Ga-CRH PET–CT is targeting CRH receptors that not only delineate corticotropinoma and provide the surgeon with valuable information for intraoperative tumor navigation but also help in differentiating a pituitary from an extra-pituitary source of ACTH-dependent CS. |

| [30] | Berkman et al. (Kantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland) | 2021 | 11C-Met (200 Mbq) + 18F-FET (300 Mbq) | PET-MRI (3.0T SPGR, contrast imaging) | 15 | 47.2 (18–69) | 7% | 12/3 | 4/15 (27%) *** | 15/15 (100%), mean tumor volume = 0.07 | 0 | Population: patients who underwent TSS for biochemically proven CD Adenoma detection: - MRI: + in 11/15 (73%) - 11C-Met PET-MRI: + in 9/9 (100%) of which 1 suggested lesion contralateral to actual lesion during surgery: PPV = 8/9 (89%) - 18F-FET-PET: + in 9/9 (100%), PPV localization = 9/9(100%) Histological confirmation: yes Outcome: Initial biochemical remission in 13/15 (87%). Recurrence in 2/15 during follow-up (1 18F-FET and 1 11C-Met/18F-FET): recurrence rate 18F-FET = 20% and 11C-Met = 50%. Non-remission rate: 1 (17%) of 18F-FET and 1 (33%) 11C-Met/18F-FET group | Preoperative hybrid 18F-FET-PET/MRI and 11C-Met-PET/MRI have a high predictive value in localizing corticotroph adenoma selective for adenomectomy in CD. Even with a limited number of patients investigated in this study, the performance of 18F-FET PET/MRI for localizing microadenoma may encourage validating studies and, thereafter, more widespread use, to give more patients access to a potentially effective, and, in terms of selectivity, a less detrimental surgical therapy option. | |

| [31] | Novruzov et al. (University College London Hospital, UK) | 2021 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE (120–200 Mbq) | PET–CT | 7 ** | 48 ± 17 (26–68) | 43% | 0/7 | X | Population: consecutive patients with suspected pituitary pathology referred for 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT Adenoma detection: 9 suspected recurrent CS: - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: pituitary + in 7/9 (78%), − in 1/9 (occult) and 1/9 uptake pancreas Pituitary uptake: 7/7 in recurrent CD 0/2 in ECS Histological confirmation.: yes Outcome: unknown | Recurrent CS is associated with positive pituitary uptake of 68Ga-DOTA-TATE. Although in these cases it would not be possible to distinguish pathological from physiological uptake, positive 68Ga-DOTA-TATE is useful as it indicates the presence of functioning pituitary tissue. The absence of pituitary uptake in patients with recurrent CS suggests an ectopic ACTH source. | |||

| [32] | Ding et al. (Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China) Prospective | 2022 | 68Ga-pentixafor (111–185 MBq) + 18F-FDG (5.55 MBq/kg) | PET–CT + MRI (rapid dynamic contrast-enhanced) | 7 ** | 38.0 ± 9.5 | 14% | 4/3 | 3/7 (43%) *** | 7/7 (100%), M ± SD = 5.9 ± 2.9 mm | 0 | Population: Cushing’s syndrome who underwent 68Ga-pentixafor Adenoma detection: - MRI: + in 4/7 (57%) -68Ga-pentixafor PET–CT: + in 6/7(86%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 1/7 (14%) De novo - MRI: + in 4/4 (100%) - 68Ga-pentixafor PET–CT: + in 4/4 - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 1/4 Recurrent - MRI: + in 0/3 - 68Ga-pentixafor PET–CT: + in 2/3 - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 0/3 Histological confirmation: unknown Outcome: unknown | 68Ga-pentixafor PET–CT is promising in the differential diagnosis of both ACTH-independent and ACTH-dependent CS. The ACTH-pituitary adenoma detection rate of 68Ga-pentifaxor PET–CT was greater than that of contrast-enhanced MRI of 18F-FDG PET–CT. | |

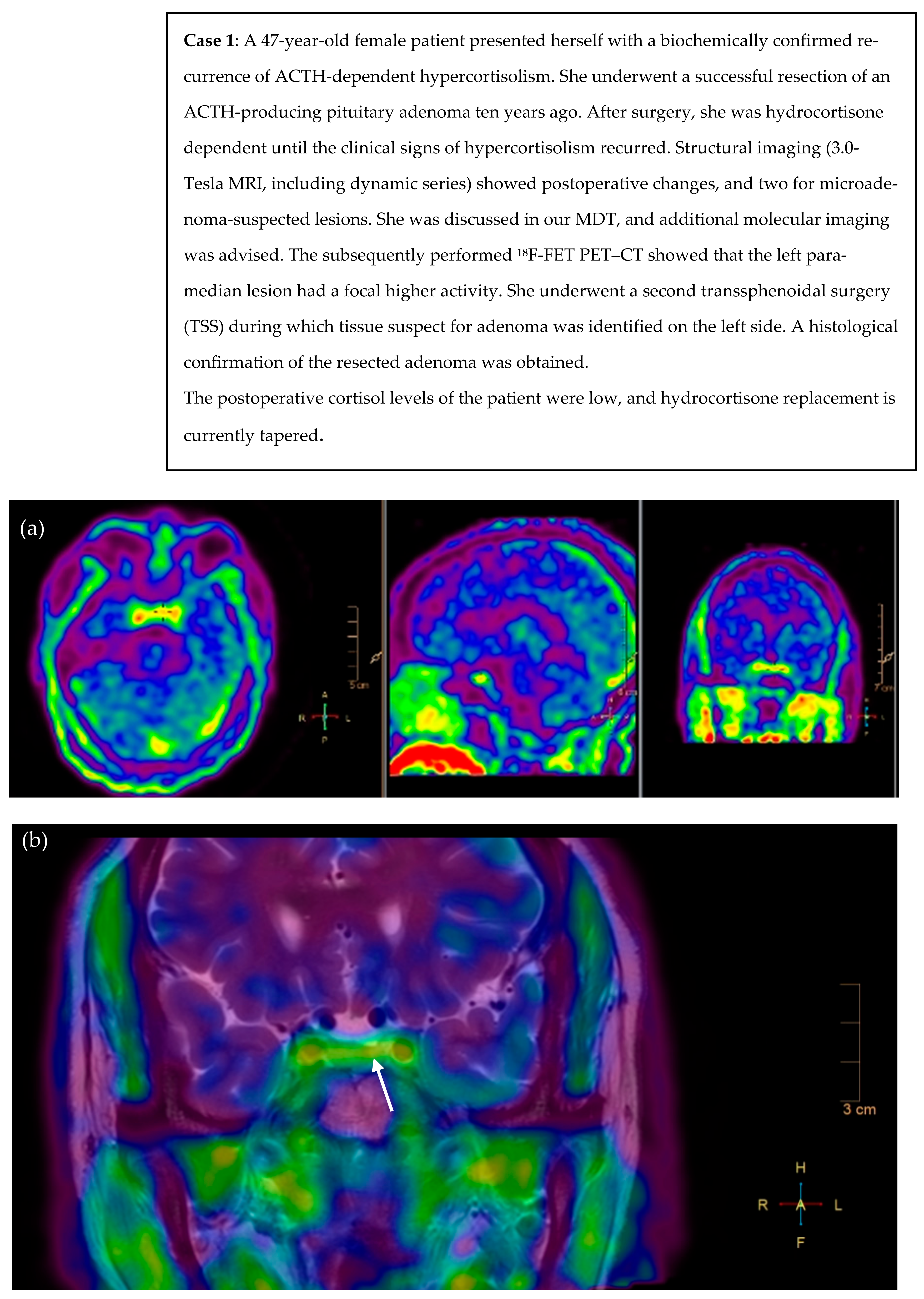

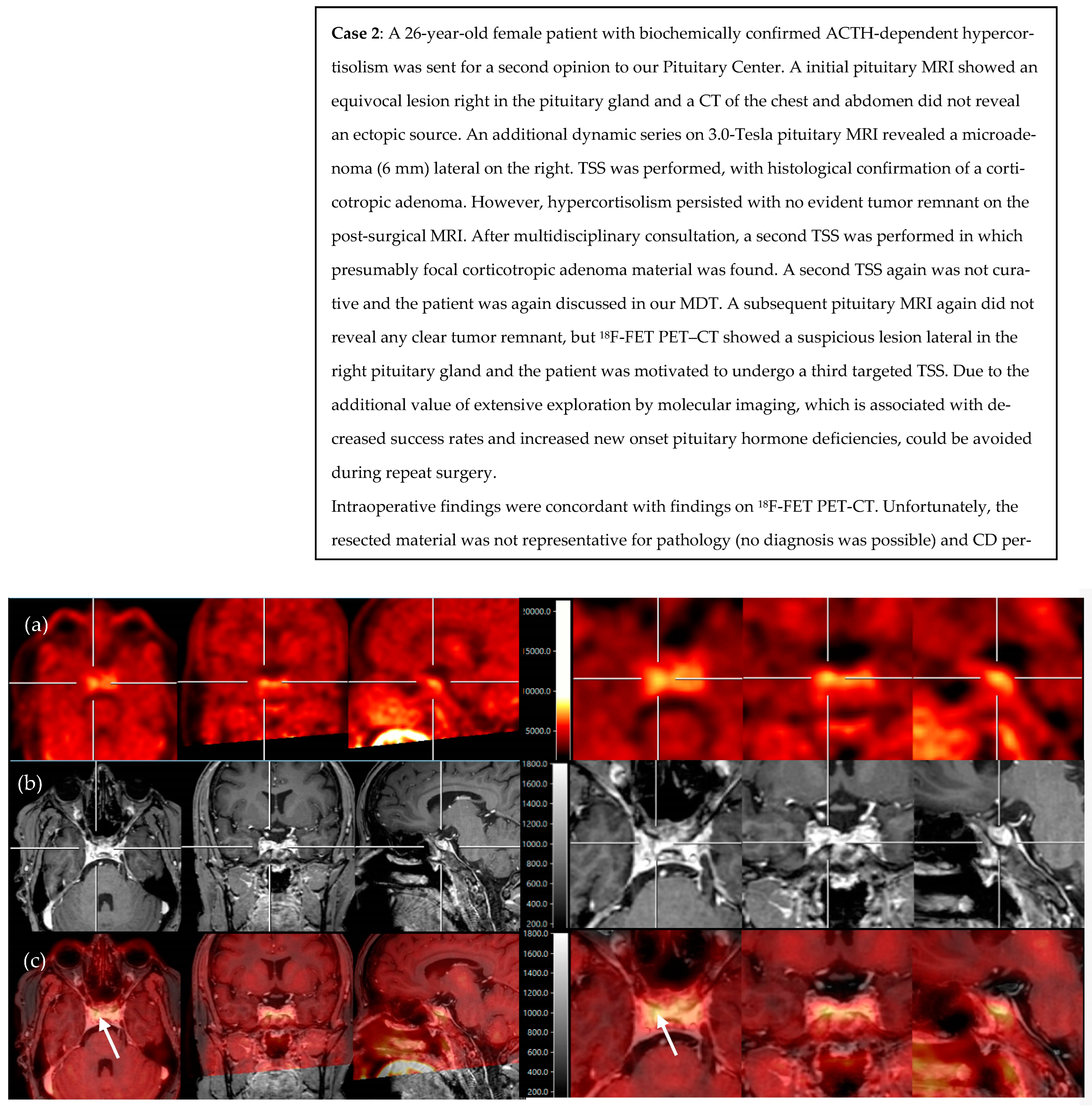

3.2. Illustrative Cases

3.3. Molecular Imaging in Ectopic Cushing’s Syndrome (See Also Table A1 and Table A2)

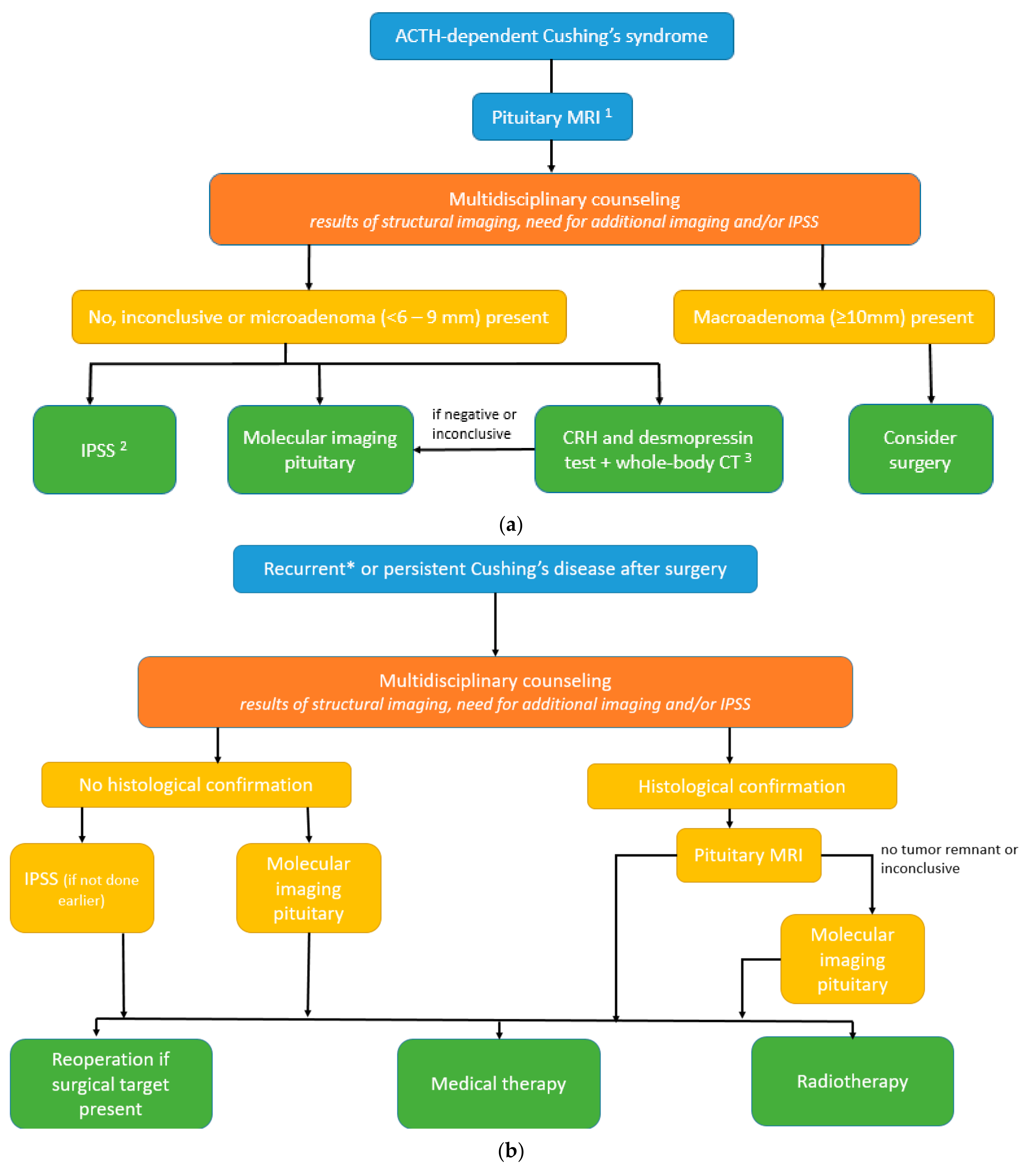

3.4. Proposal of Diagnostic Algorithms in ACTH-Dependent Cushing’s Syndrome (See Also Figure 3a,b)

- If (optimized) structural imaging remains negative or equivocal or shows a microadenoma (<10 mm), and clinical presentation including biochemical testing is suggestive of Cushing’s disease (high “pretest probability”; young women with gradual onset and mildly elevated ACTH levels);

- If CRH and desmopressin test and whole-body CT (or whole-body 68Ga-SSTR PET–CT) in the search for ECS is inconclusive;

- Presence of contraindications to IPSS (renal failure, blood clotting disorders, or allergy to dye contrast).

- Persistent or selected cases of recurrent Cushing’s disease (equivocal biochemical response) after transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) and without histological confirmation.

- Persistent or selected cases of recurrent Cushing’s disease (equivocal biochemical response) after TSS and with histological confirmation, but no or inconclusive adenoma remnant localization on the pituitary MRI (illustrative cases 1 and 2).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Ref. | Author | Year | Tracer | Imaging Modalities | Population | Aim | Results | Conclusions of Authors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age | Sex * | Diagnosis | Imaging | |||||||

| [48] | Pacak et al. (National Institutes of Health, USA) Prospective | 2004 | 18F-FDG (20 mCi) | PET | 17 | 43 ± 13 (22–69) | 59% | Assess 18F-FDG–PETsensitivity for detection of ACTH-secreting tumors and comparison with conventional imaging. | (Pulmonary) carcinoid, insulinoma, gastrinoma, somatostatinoma, olfactory esthesioneuroblastoma, SCLC, and metastatic carcinoid | Population: ACTH-secreting tumors Routine imaging + FDG–PET, H-OCT if L-OCT was negative > localized in 13/17 (76%), occult in 4/17 (24%) ECS detection: true positives/false positives - CT (n = 17): 9/17 (53%)/3/17 - MRI (n = 16): 6/16 (37%)/3/16 - 18F-FDG–PET (n = 17): 6/17 (35%)/4/17 Localization: 18F-FDG -PET concordant with CT and/or MRI in 6 true positives; L-OCT in 8 true positives. 18F-FDG–PET did not reveal additional tumors beyond those identified on CT or MRI; the smallest detected lesion = 1.3 cm. - positive scans were typically more aggressive (NET, olfactory neuroblastoma, SLCL) - negative scans were less aggressive (pulmonary carcinoids) or a form of tumoral hibernation Outcome: 12 underwent surgery: ACTH staining: 8+, 1- but hypercortisolism resolved after resection, 2 not available 2 with + imaging and biopsy-proven ACTH-secreting tumors did not undergo surgical resection 4 remained with occult disease | 18F-FDG–PET is inferior to CT/MRI and does not detect additional ACTH-secreting tumors causing CS (occult tumors on CT/MRI). Because hyperplastic adrenal glands may show 18F-FDG–PET and/or OCT uptake, an adrenal ACTH-secreting lesion may be obscured. Recommend that CT, MRI, and L-OCT be used to screen for tumors. Modalities are complementary: single + study may represent false +, more than 1 + study = confirm true lesion. |

| [68] | Zemskova et al. (National Institutes of Health, USA) Prospective | 2010 | 18F-FDG + F-DOPA | PET | 11 (41 total) | Proven: 45 ± 13.6 (23–69), occult: 54 ± 14.4 (33–82) (total) | Proven: 43%, occult: 73% (total) | Evaluate the utility of 18F-FDG and other modalities. | Population: 41 patients with ECS based on IPSS > 11/41 (27%) remained occult, and 30/41 (73%) resected tumors. In tumor-identified patients (n = 30): sensitivities per patient/positive predictive value per lesion/proportion of FP lesions/fraction of patients with ≥ 1 false+ findings - CT—neck/chest/abdomen/pelvis (n = 30) = 28/30 (93%)/66%/34%/50% - MRI—neck/chest/abdomen/pelvis (3T, n = 29) = 26/29 (90%)/74%/26%/31% - 18F-FDG–PET (n = 11) = 7/11 (64%)/53%/47%/18% - F-DOPA-PET (n = 11) = 6/11 (55%)/100%/0%/x In all patients with EAS (n = 41): sensitivities per patient/positive predictive value per lesion/proportion of FP lesions - CT—neck/chest/abdomen/pelvis = 28/41 (68%)/57%/43% - MRI—neck/chest/abdomen/pelvis (3T) = 26/40 (65%)/67%/ 33% - 18F-FDG–PET = 7/14 (50%)/50%/50% - F-DOPA-PET = 6/13 (46%)/89%/11% PET detected only lesions also seen by CT/MRI; abnormal F-DOPA-PET improved PPV of CT/MRI. | High sensitivity and positive predictive value suggest thoracic CT/MRI + L-OCT for initial imaging, with lesions confirmation by 2 modalities. | |

| [53] | Kumar et al. (Guy’s Hospital, London) | 2006 | 18F-FDG | PET | 3 | 44 + 24 + + 74 | 33% | Report on the use of 18F-FDG–PETscanning in the evaluation of ECS. | Carcinoid: right atrium and lung (2) | ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 2): ECS in 2/2 - X-thorax (n = 1), - in 1/1 - CT—chest (n = 3): + in 1/3 (nodule lung), − in 2/3 - CT—abdomen (n = 2): + but bilateral adrenal hyperplasia - MRI—chest (n = 2): + in 1/2, − in 1/2 - MRI—pituitary (n = 2): − in 2/2 - 18F-FDG–PET whole body (n = 3): + in 3/3 | 18F-FDG–PET assisted in localizing small metabolically active NETs, suggesting this imaging modality may have a useful role in identifying NET-causing CS as a result of ECS. 18F-FDG–PET is useful where conventional imaging modalities fail/changes of uncertain significance. |

| [54] | Moraes et al. (Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho, Brazil) | 2008 | 18F-FDG | PET | 2 | 31 + 53 | 50% | Report utility of 18F-FDG–PETin localization of 2 ECS tumors, where conventional imaging failed to definitively identify lesions. | Carcinoid + possible cervix | ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 1): ECS in 1/1 - CT—thorax (n = 2): + in 1/2 (lung nodule), − in 1/2 - MRI—abdomen/pelvis (n = 1): + in 1/1 (hepatic, iliac, femoral, and lumbar secondary implants) - MRI—pituitary (n = 2): − in 2/2 - 18F-FDG–PET (n = 2): + in 2/2 | C/18F-FDG–PETmay have a role in the investigation of an ECS where conventional imaging studies were not diagnostic. |

| [49] | Xu et al. (Rui Jin Hospital, China) | 2009 | 18F-FDG (0.12–0.15 mCi/kg) | PET–CT | 5 | 50 ± 14 (27–64) | 60% | Report on the use of 18F-FDG PET–CT in localization of EAS tumors in ECS. | Pulmonary carcinoma (2), thymoma (1), thymic carcinoma (1) | ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 2): ECS in 2/2 - MRI—pituitary (n = 4): − in 3/4, + in 1/4 (possible microadenoma) - CT—abdomen (n = 5): − in 1/5, + in 4/5 (bilateral adrenal hyperplasia) 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 5/5 positive 5 NETs and also 1 pneumonia, 2 hyperplasia adrenals Outcome: 4/5 resection: 3 biochemical releases, 1 clinical release 1/5 died due to severe infection and electrolyte disorders | 18F-FDG PET–CT increases the accuracy of tumor localization and further improves prognosis by curative resection. CT may localize the source better and PET reduces the false + rate. PET provides metabolic information and may reveal lesions that potentially mislead CT. |

| [50] | Doi et al. (Tokyo Medical and Dental University Graduate School, Japan) | 2010 | 18F-FDG | PET | 9 (16 total) | 58.4 ± 19 (total) | 44% (total) | Evaluate the clinical, endocrinological, and imaging features, management, and prognosis of 16 EAS. | Lung carcinoma (3), thymic hyperplasia (1), bronchus carcinoma (1), olfactory neuroblastoma (1), gastric NEC (1), pancreatic NEC (1) | Population: 16 EAS: 10/16 proven and 6/10 occult/unknown ECS detection: - IPSS: 13/15 (87%) no ACTH gradient - CT/MRI: + in 8/16 (50%) and − in 8/16 (50%) - 18F-FDG–PET: + in 1/9(11%, SCLC, also + on CT/MRI/SRS), - in 8/9 (1 + on CT/MRI, 2 + on SRS, 5 also - other) | To localize ECS, a combination of dynamic endocrine tests and imaging tests, including anatomical modalities (CT and MRI) and functional modalities (SRS and 18F-FDG–PET) is required. 18F-FDG–PETis known to identify tumors with high proliferative activities: modality seems limited to localizing malignant tumors with a highly aggressive and invasive nature. |

| [66] | Dutta et al. (All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India) | 2010 | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC | PET–CT | 2 | 29 + 23 | 50% | Describe the utility of 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT and clinic-pathological features in 4 thymic carcinoid tumors. | Thymic carcinoid tumors (4) | Population: 2 cases of thymic carcinoid (stage 2 and 3): ECS localization: - BIPSS: ECS in 2/2 - CECT—chest: + in 2/2 - MRI—pituitary: − in 2/2 - 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT: − in 2/2 | Unlike pulmonary and abdominal carcinoids, 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT has not proven useful in thymic carcinoids. |

| [45] | Ejaz et al. (University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) | 2011 | 18F-FDG | PET | 6 (20 total) | 48 [19–75] (total) | 40% (total) | Study our institutional experience with CS-EAS and further understand this entity in a cancer center. | Bronchus carcinoid (9), SCLC (9), medullary thyroid carcinoid (4), pancreatic NET (3), thymic carcinoma (3), urinary bladder NET (1), small bowel carcinoma (1), metastatic NET (1) | ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 8): EAS in 8/8 - pituitary MRI (n = 34): − in 31/34 (91%), + in 3/31 (9%) (incidental pituitary abnormalities) - CT/MRI—chest (n = 37): + in 25/37 (68%) - CT/MRI—abdomen (n = 32): + in 9/32 (28%) - 18F-FDG–PET(n = 6): + in 4/6 (67%; all also on CT/MRI), - in 2/6 (33%) | 18F-FDG–PET localized ACTH sources in four of six patients in whom primary tumor was also observed on less expensive cross-sectional imaging studies. |

| [47] | Boddaert et al. (Georges Pompidou European Hospital, France) | 2012 | 18F-FDG + 18F-DOPA | PET | 6 (12 total) | 40 (16–63) (total) | 57% (total) | Revisit characteristics and outcomes of ACTH-secreting bronchial carcinoid tumor responsible for CS. | Bronchial carcinoids tumors (14; of which 11 are typical and 3 atypical) | Population: 14 bronchial carcinoid tumors causing CS. ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 6): ECS in 6/6 - Pituitary MRI (n = 14): − in 10/14 (71%), + in 4/14 (29%; 3/4 suggestive adenoma, 1/4 Rathke’s cleft cyst) - X-thorax (n = 14): − in 12/14 (86%), + in 2/14 (14%; 1 basithoracic nodule + 1 diffuse reticulonodular lesion) - CT—thorax (n = 14): + in 9/14 (64%), − in 5/14 (36%) + in other 5: tumor detected with mean delay 68 months - CT—abdominal (n = 12): + in 4/12 (33%; bilateral adrenal hyperplasia and 2/12 abnormal adrenal nodular pattern) - 18FDG-PET: + in 3/4 (75%, moderately abnormal), − in 1/4 - 18F-DOPA-PET: + in 1/2 (50%), − in 1/2 (50%) | 18F-FDG–PETis of limited use in these tumors because of its low metabolic activity. New and more specific markers of carcinoid tumors are currently available, including 18F-DOPA or 11C-5 HTP. |

| [58] | Giraldi et al. (European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy) | 2013 | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC (3 MBq/kg) | PET–CT | 5 | 37–67 | 20% | Report experience with 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT in 5 patients with clinical and biochemical evidence of EAS tumors of unknown origin. | Typical carcinoid (3) | ECS localization: - MRI—pituitary: − in 3/5, + in 2/5 (pituitary adenoma) - BIPSS (n = 2): ECS in 2/2 - Conventional imaging (n = 5): + in 2/5 (40%), − in 3/5 (60%) - 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT: + in 5/5 (100%), − in 0/5 including 1 false + (left adrenal: hyperplasia) | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT can direct diagnosis in a noninvasive way, eliminating the need for an invasive procedure. However, physiological uptake in the pituitary/spleen/adrenals/head/pancreas may limit sensitivity (false + in one patient). |

| [62] | Özkan et al. (Instanbul University Instanbul Medical Faculty, Turkey) | 2013 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE (3–4 mCi) + 111In (5 mCi) | PET–CT + SPECT–CT | 5 (19 total) | 37.8 | 32% | Evaluate the value of SSTR imaging with OCT and 68Ga-DOTA-TATE in localizing ectopic ACTH-producing tumors. | Pulmonary carcinoid (6), pancreatic NET (1), metastatic foci atypical carcinoid of unknown origin (1) | Population: 8/19 (42%) ectopic site detected ECS localization: Of ectopic foci: + in 7/8 (88%) on OCT or 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT, − in 1/8 (metastatic foci) 6 pulmonary carcinoids: - 4/6 + on OCT (all also on CT) - 1/6 - on OCT, follow-up CT after 3 years: nodule upper lobe (carcinoid) - 1/6 + on 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT, prior false- evaluated on CT (atypical pulmonary carcinoid) 1 pancreatic NET: detected on MRI + OCT scan 1 metastatic focus atypical carcinoid after resection mediastinal mass + lymph nodes: metastatic lymph nodes and bone lesions on OCT; 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT showed progression of the disease. OCT: performed in 16/19 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: performed in 5/19 11 patients: EAS site could not be detected; - 10/11 - (scans + uptake) - 1/11: 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT false + (mass adrenal gland on CT with moderate 68Ga uptake > adenoma without ACTH staining) | Somatostatin receptor imaging has a complementary role with radiological imaging in localizing ectopic ACTH secretion sites. PET–CT imaging with 68Ga peptide conjugates is a promising new modality for this indication. Since pulmonary carcinoid tumors are responsible for ECS in most cases, thoracic regions must be evaluated with great care. |

| [69] | Wahlberg and Ekman (Linköping University, Sweden) | 2013 | 11C-5-HTP | PET | 1 | 63 | 0% | Describe diagnostic challenges to find a tumor in CS secondary to ECS in 2 cases with (a)typical pulmonary carcinoid. | Pulmonary carcinoid (atypical) | ECS localization: - BIPSS: ECS in 1/1 - MRI—pituitary: - in 1/1 - CT—neck/thorax/abdomen: enlargement of the left adrenal - 11C-5 HTP–PET: + in 1/1: 8 mm mass left lung with focal uptake in retrospect: the same shadow was present on thoracic CT, previously assessed as a vessel | Diagnostic evaluation time is limited due to the aggressive course in ECS. We suggest that 11C-5-HTP–PET could be considered early as a secondary diagnostic tool when primary CT and/or MRI fail to show tumor. |

| [52] | Gabriel et al. (La Timone & North University Hospital, France) Prospective | 2013 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE + 111In | PET–CT + SPECT | 5 (32 total) | 22–80 (total) | 41% (total) | Perform head-to-head comparison between 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT and standard imaging work-up of NET that included multiphasic CT, liver MRI, and SRS SPECT. | Lung NET (4; of which 2 typical and 2 atypical) | Population: 32 NET > 5 cases ectopic ACTH secretion: 4 lung NETs and 1 remained occult after all imaging ECS localization: - Conventional imaging (CT/MRI): + in 2/5 (40%), - in 3/5 (60% of which 1 typical, 1 atypical, and 1 occult) - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: + in 2/5 (40%; both - on CT), − in 3/5 (60%; 2 false- and 1 occult also on CT) | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT detected a similar number of sites with a combination of SRS, liver MRI, and thoraco-abdominopelvic CT on region-based analyses and missed half of the primary lung carcinoids with ECS. |

| [55] | Kakade et al. (KEM Hospital Mumbai, India) | 2013 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE+ 18F-FDG | PET + CT + MRI (3D VIBE) | 6 (17 total) | 42.67 (20–63) | 67% | Analyze clinical, biochemical, and imaging characteristics; management strategies and outcomes of EAS. | Bronchial carcinoids (6), thymic (1), metastatic (2), medullary thyroid carcinoid (1) | ECS localization: - IPSS: ECS in 8/8 - MRI—pituitary: − in 12/17 (71%), + in 5/17 (29%; suspicious microadenoma > TSS > uncured) - CT (n = 17): + in 15/17 (88%), − in 2/17 (both + on 68Ga- DOTA-TATE PET–CT) - MRI (3D VIBE): true+ (+MRI in CD) = 111, false- (-MRI in CD) = 90, false+ (+MRI in EAS) = 5, false- (-MRI in EAS) = 12 > sensitivity = 55%, specificity: 70.5%, PPV: 95.6% - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET (n = 6): + in 4/6 (67%), − in 2/6 (33%, both + on CT) - 18F-FDG–PET: 4/4 positive (mapping of disease burden) | Some lesions are better diagnosed by anatomical rather than functional scans, but functional imaging may help in cases where anatomical imaging fails. |

| [63] | Goroshi et al. (KEM Hospital Mumai, India) | 2016 | 68Ga-DOTA-NOC (3–5 mCi) | PET–CT + CECT | 12 | 35.5 (22–45) | 42% | Review the performance of 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT and CECT in 12 consecutive EAS patients. | Population: 11 overt cases, 1 remained occult. 13 lesions in 11 patients (true +) ECS localization: - CECT (n = 13): + in 12/13 (92%, of which 5 false +), PPV = 71% -68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: + in 9/13 (69%, of which 0 false+ > PPV = 100%) | CECT remains the first-line investigation in EAS localization, and 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT can be added to enhance the PPV of suggestive lesions. | |

| [59] | Venkitaraman et al. (All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India) | 2014 | 18F-FDG + 68Ga-DOTA-TOC | PET–CT | 3 | 42, 45, 28 | unkn | Share experience in successful localization of ectopic EAS in 3 patients with 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT, who later underwent surgical resection and had complete resolution of symptoms. | Typical carcinoid lung (3) | ECS localization - MRI—pituitary (n = 3): − in 3/3 - CT—chest (n = 3): + in 3/3 - 18F-FDG PET–CT (n = 3): − in 3/3 - 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT (n = 3): + in 3/3 Outcome: 3/3 the complete resolution of symptoms | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT successfully localized ectopic source in all three and also detected the spread to the mediastinal lymph nodes; thus, not only helped in localizing tumors but also influenced surgical decision making. |

| [70] | Karageorgiadis et al. (National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA) | 2015 | 18F-FDG + 68Ga-DOTA-TATE | PET–CT + SPECT | 7 | Median: 13.6 (1–21) | 57% | Discussion of localization, work-up, and management of ACTH/CRH co-secreting tumors in children and adolescents. | Metastatic hepatic NET, metastatic pancreatic NET (primary tumor: 2 lobular mass and 1 distal pancreatic tail), thymic carcinoid (3), bronchogenic carcinoid, pancreatoblastoma | ECS localization: - IPSS (n = 5): ECS in 4/5 - MRI—pituitary (n = 6): - in 4/6, + in 2/6 (hypoenhancing segments suggestive of macroadenomas > 1 TSS) - Abdominal or chest MRI and CT (n = 7): + in 7/7 - 18F-FDG PET–CT (n = 5): + in 4/5 (true positives) - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT (n = 1): 1/1 uptake | Extremely rare, diagnosis is frequently missed and sometimes confused with CD due to the effect of CRH on the pituitary. |

| [25] | Koulouri et al. (Wellcome Trust-MRC Institute of Metabolic Science) | 2015 | 11C-Met (300–400 MBq) | PET–CT + MRI (SPGR) | 2 | 42 + unknown | unknown | Report experience of functional imaging with 11C-Met PET–CT/MRI in the investigation of ACTH-dependent CS. | Small bowel primary NET + primary breast tumor | ECS localization: 11C-Met PET–CT: 2/2 Very little uptake in pituitary fossa, but distant sites of metastasis were detected, with subsequent histology confirming ACTH-stained NET | 11C-Met PET–CT can aid the detection of ACTH-secreting tumors in CS and facilitate targeted therapy: may help inform decision making in EAS with an incidental NFA + source of ECS (including metastases) may be identified. |

| [71] | Sathyakumar et al. (Christian Medical College, India) | 2017 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE + 68Ga-DOTA-NOC + 18F-FDG | PET–CT | 7 scans (total N = 21) | 34 (19–55) (total) | 67% (total) | Describe the experience with ECS. | Thymic carcinoid (1), bronchial carcinoid (4) | ECS localization: - CT—chest: (n = 17): + in 12/17 (71%), − in 5/17 (29%) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: (n = 1): + in 1/1 - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: + in 4/5 (80%, of which 3/4 also + on CT), − in 1/5 (20%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: + in 2/2 (100%) | ECS is most commonly seen in association with intrathoracic tumors such as bronchial or thymic carcinoid. |

| [46] | Deldycke et al. (AZ Sint-Jan Hospital Bruges) | 2018 | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC + 18F-FDG | PET–CT | 1 | 68 | 100% | 4 case descriptions, highlighting diagnostic challenges and treatment options in paraneoplastic CS. | occult | ECS localization: - BIPSS: ECS in 1/1 - CT: − in 1/1 (no overt tumor; small lung nodule but no malignant aspect, stable upon re-evaluation) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: − in 1/1 - 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT: − in 1/1 Outcome: not controlled by SSA/ketoconazole so bilateral adrenalectomy, at follow-up no primary tumor identified | |

| [65] | Varlamov, Hinojosa and Fleseriu (Oregon Health & Science University, USA) | 2019 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE + 111In + 18F-FDG | PET–CT, SPECT, pituitary MRI, body CT or MRI | 6 | 54.6 (±16.1) | 17% | Report on 6 consecutive patients with confirmed active and occult ECS who underwent 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT. | Occult (4), pancreatic NET (1) | ECS localization: - IPSS (n = 4): ECS in 4/4 - pituitary MR (n = 6): − in 3/6, + in 3/6 (2x 4 mm + 1x 3 mm > 1 patient TSS but later D/pancreatic tumor) - CT body (n = 6): − in 1/6, + in 5/6 - 18F-FDG PET–CT (n = 5): − in 2/5, + in 3/5(of which 2 false +) - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT (n = 6): − in 4/6, + in 2/6 Outcome: 2 occult: medical therapy with ketoconazole/mifepristone, 2 bilateral adrenalectomy | Center experience demonstrates a lower than previously reported 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT sensitivity for ECS, especially in occult lesions. We suggest that data on this tracer in ECS is subject to publication bias and false – are likely underreported; its diagnostic value needs further study. 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT suggestive of ECS source in one overt case (seen on CT) and did not help identify a culprit lesion in five occult lesions. |

| [60] | Wannachalee et al. (3 tertiary referral centers: University of Michigan, Mayo Clinic Rochester + The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA) | 2019 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE | PET–CT | 28 | 50 (38–64) | 21% | Determine the efficacy for ECS localization and clinical benefit of 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT. | Bronchial (5), thymic (1), pancreatic (1), metastatic NET of unknown origin (1) | Population: 28 ECS: 17/28 identified, 15/28 occult ECS localization: - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: + in 11/17 (65%; 7/11 solitary and 4/11 metastatic), − in 6/17 1 false +: adrenocortical hyperplasia 1 false-: lever metastasis First modality to localize in 2/17 Outcome: Follow-up (n = 11) 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: 7/11 (64%) changes in clinical management (4/7 no change) > identified 9 new metastatic foci and 3 recurrent tumors (5 solitary bone, 3 pancreatic, 1 abdominal lymph) | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT is sensitive in detecting primary and metastatic ECS, often identifies occult tumors after conventional imaging, and impacts clinical care in the majority of patients. A somewhat lower accuracy in this series might reflect selection bias for difficult cases at referral centers, with a high prevalence of occult ECS. |

| [64] | Ceccato et al. (University Hospital of Padova, Italy) | 2020 | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC + 68Ga DOTA-NOC (2 MBq/kg) | PET–CT | 18 | 44% | Study the diagnostic accuracy of CT with 68Ga-SSTR PET–CT in localizing ACTH-secreting tumors in patients with EAS. | Bronchial carcinoma (11), SCLC (2), pancreatic NET (1) | Population: 18 ECS cases (16 primary + 2 recurrent neoplasms) > 8 overt and 10 occult: 6/10 covert after careful follow-up and 4/10 remained occult ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 10): ECS in 10/10 - CT (n = 18) + in 11/18 (61%), − in 7/18 (39%) - 68Ga-SSTR PET–CT: + in 12/28, − in 16/28 Overt cases: (n = 8) - de novo overt ECS: CT + in 4/6, 68Ga-SSTR + in 6/6 - recurrent/relapse ECS: CT + 2/2, 68Ga-SSTR + in 1/2 Occult cases (n = 10, 6/10 localized after careful FU) - 1 + on CT, never showed pathological uptake 68Ga-SSTR - 1 + on 68Ga-SSTR, not found on conventional radiology Baseline: - CT (n = 16): + in 4/16, 1/16 inconclusive, − in 12/16 (of which 2+ on 68Ga-SSTR) - MRI (n = 6): - in 6/6 - 68Ga-SSTR PET–CT (n = 16): + in 6/16, − in 10/16 Follow-up: - CT (n = 15): + in 7/15, − in 8/15 (of which 1 + on 68Ga) - MRI (n = 3): + in 2/3, − in 1/3 - 68Ga-SSTR PET/CT (n = 12): + in 6/12, − in 6/12 (of which 2+ on CT) | 68Ga-SSTR PET–CT is useful in localizing EAS, especially to enhance positive prediction of the suggestive CT lesions and to detect occult neoplasms. However, it presents a considerable number of indeterminate/false+ images that need careful interpretation. Nuclear and conventional imaging should be repeated during follow-up (occult + overt). | |

| [61] | Bélissant et al. (Hôpital Tenon APHP and Sorbonne University) | 2020 | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC (1.2–2 MBq/kg)+ 18F-FDG + F-DOPA | PET–CT + CECT | 19 | Range: 26–71 | 26% | Report experience with 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT in localizing causal NET in case of initial but also recurrent paraneoplastic Cushing’s syndrome, and its clinical impact. | ECS localization: Primary NET (sensitivity/accuracy): - CECT: 2/7 (29%)/3/9 (33%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: 1/6 (17%)/1/7 (14%) - DOPA PET–CT: 0/6 (0%)/0/6 (0%) - 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT: 4/8 (50%)/5/9 (55%) Persistence: (n = 3) or recurrence (n = 4) of PCS (sensitivity per patient/sensitivity per lesion/accuracy per lesion): - CECT: 2/7 (29%)/2/9 (22%)/2/9 (22%) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: 0/3 (0)/0/3 (0)/0/4 (0) - DOPA PET–CT: 0/1 (0)/0/1 (0)/0/1 (0) - 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT:6/7(86%)/9/10 (90%)/9/11(82%) Outcome: 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT clinical impact: 3/13 (23%) primary NET and DOTA-TOC PET/CT alone had a clinical impact in 4/7 (57%) persistent patients. | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC PET–CT seems to be a valuable tool for the detection of NET responsible for persistent/recurrent paraneoplastic Cushing’s syndrome after surgery (more effective than the detection of causal tumor initial PCS). Also valuable for staging when primary NET is easily found > help localize additional lesions (small lymph nodes). | |

| [29] | Walia et al. (Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, India) Prospective | 2021 | 68Ga-tagged CRH (111–185 MBq) | PET–CT | 3 | unknown | 33% | Evaluate the role of 68Ga-CRH PET–CT for the evaluation and management of ACTH-dependent CS. | Bronchial NET (2), pancreatic NET (1) | ECS localization: - BIPSS (n = 1): central gradient - MRI—pituitary (n = 3): − in 2/3, + in 1/2 (suspicious lesion 3 × 4 mm) - 68Ga-CRH PET–CT: detection of primary NET = 3/3 uptake tracer in sella: + in 1/3 (diffuse), − in 2/3 Outcome: 1 resolution after surgery and 1 died before surgery | 68Ga-CRH PET–CT represents a novel, noninvasive molecular imaging, targeting CRH receptors that not only delineate corticotropinoma and provide the surgeon with valuable information on intraoperative tumor navigation but also help in differentiating a pituitary from an extra-pituitary source of ACTH-dependent CS. |

| [51] | Zisser et al. (Vienna general hospital, Italy) | 2021 | 18F-FDG (5 MBq/kg) + 18F-DOPA (3 MBq/kg) + 68Ga-DOTA-NOC (3 MBq/kg) | PET–CT | 18 | 51 ± 18 (confirmed: 43±17; occult: 57±16) | 58% (con: 62%, occ: 50%) | Evaluate the diagnostic feasibility of 18F-FDG, 18F-DOPA, 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT in ECS. | Pulmonary NET, SCLC, papillary thyroid carcinoma | Population: 18 ECS: confirmed (n = 7; all visible on conventional imaging), highly suspected without histology (n = 1), and occult (n = 10). ECS detection: - CT—chest (n = 12): + in 6/12 (50%; 5/6 true+ and 1/6 false+) - MRI—chest (n = 1): + in 0/1 - CT—abdomen (n = 10): + in 0/10 - MRI—abdomen (n = 5): + in 0/5 - 18F-FDG PET–CT (n = 11): + in 5/11 (3/5 true+, 2/5 false+) - 18F-DOPA PET–CT (n = 11): + in 3/11 (3/3 true+, 0 false+) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT (n = 8): + in 4/8 (3/4 true+, 1 false+) Confirmed cases: (n = 7) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: true+ in 3/6 (50%), false- in 3/6 (50%) sensitivity = 50%, specificity = 60% (3/5), PPV = 60%, NPV = 50%, accuracy = 55% (6/11) - 18F-DOPA PET–CT: true+ in 3/4 (75%), false− in 1/4 (25%) sensitivity = 75%, specificity = 7/7 (100%), PPV 100%, NPV 88%, accuracy = 90% (10/11), - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: true+ in 3/3, false− in 0 sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 80% (4/5), PPV = 75%, NPV = 100%, accuracy = 88% (7/8) | 68Ga-DOTA-NOC and 18F-DOPA PET–CT superior results compared to 18F-FDG. The sensitivity might be influenced by the etiology of the underlying tumor. 68Ga-DOTA-NOC is a highly recommendable tracer for tumor detection in ECS, and F-DOPA has promising results (especially specificity) but needs further assessment; FDG can be complementary. |

| [31] | Novruzov et al. (University College London Hospital, UK) | 2021 | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE (120–200 MBq) | PET–CT | 8 | 50 ± 23 (14–78) | 25% | Investigate the utility of 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT in patients with suspected pituitary pathology. | Bronchial carcinoma (3 of which 2 typical), small bowel NET (1), pancreatic NET (1) | Population: ECS: 6 de novo and 2 suspected recurrent CD ECS detection: - 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET–CT: + in 6/8 (75%), −in 2/8 (25%) + = 5/6 (83%) de novo and 1/2 (50%) recurrent First to localize in 1/5 (terminal ileum) 2 cases occult: not shown on any imaging modality > 1/2 detected on EUS (pancreatic NET) and 1/2 occult | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE is useful in CS for the detection of ectopic sources of ACTH production, especially when anatomic imaging is negative. |

| [56] | Hou et al. (Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China) | 2021 | 18F-FDG (5.55 MBq/kg) + 68Ga-DOTA-NOC (111–148 MBq) + 99mTc | PET–CT/SPECT-CT | 24 | 38 ± 17 (9–72) | 54% | Evaluate the usefulness of 18F-FDG PET–CT for differentiating ectopic ACTH-secreting lung tumors from tumor-like pulmonary infections in patients with ECS. | Lung tumors (18, of which 12 are typical, 5 atypical, 1 SLCL) | Population: 24 cases with pulmonary CT nodules and occult source of ECS (18 lung tumors and 6 pulmonary infections) ECS detection: - MRI—pituitary: − in 18/24 (75%), - 18F-FDG PET–CT: SUVmax of infections higher than tumors, SUVmax > 4.95 = differentiating 75% sensitivity and 94% specificity. - SRI: (n = 15 of which 6 99mTc + 9 68Ga): lung tumors: sensitivity = 6/11 (55%) and spec = 50% lung infections: + in 2/4 (50%; 3/4 99mTc) | Pulmonary infections exhibit higher 18F-FDG uptake than ACTH-secreting lung tumors. An SUVmax cut-off value of 4.95 may be useful for differentiating the two conditions. SRI may not be an effective tool for differentiating the two conditions (low specificity). |

| [32] | Ding et al. (Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China) | 2022 | 68Ga-pentifaxor | PET–CT | 1 | 39 | 100% | Investigate the performance of 68Ga-pentixafor in CS. | Case of metastatic ECS: multiple hypermetabolic lesions, no pituitary uptake, increased adrenal uptake | Promising in the DD of both ACTH-independent and ACTH-dependent CS. Activated CXCR4 molecular signaling along the pituitary–adrenal axis was found in patients with Cushing’s disease. | |

| [57] | Zhang et al. (The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, China) | 2022 | 18F-FDG (5.55 MBq/kg) + 68Ga-DOTA-NOC (111–185 MBq) | PET–CT | 68 | 51 [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] (19–72) | 44% | Compare the diagnostic efficacies of 18F-FDG and 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT in EAS. | Anterior mediastinal/thymic (21), bronchial carcinoid (9), pancreatic NET (10), paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma (3), medullary thyroid carcinoma (2), olfactory neuroblastoma (2), occult (21) | Population: 68 cases: 37/68 (54%) for tumor localization, 31/68 (46%) to evaluate tumor load/metastasis (staging) ESC detection: Localization group (n = 37): primary tumor detected in 18/37 (49%) Scan-based: (n = 37) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: true+ in 7/37 (19%), false+ in 8/37 (22%) and false- in 1/37 (3%) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: true+ in 17/37 (46%), false+ in 1/37 (3%) and false- in 1/37 (3%) Lesion-based: (n = 29): - 18F-FDG PET–CT: true+ in 7/29 (24%), false+ in 9/29 (31%) and false− in 1/37 (3%) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: true+ in 17/29 (59%), false+ in 1/29 (3%) In overt EAS (n = 18) - 18F-FDG PET–CT: sensitivity = 7/18 (39%) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: sensitivity = 17/18 (94%) 6/18 (33%) + on both, 11/18 (61%) + only in 68Ga, 1/18 (6%) only + in FDG Staging group (n = 31): 11/31 after primary tumor resection with 286/292 confirmed as tumor lesions. 28/31 (90%) patients with detected tumor lesions. Scan-based: - 18F-FDG PET–CT: true+ in 26/31 (84%), false+ in 4/31 (13%) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: true+ in 21/31 (68%), false+ in 3/31 (10%) Lesion-based: -18F-FDG PET–CT: true+ in 274/292(94%), false+ in 4/292(1%) - 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT: true+ in 160/292 (55%), false+ in 3/392 (1%) 148/286 (52%) + on both exams; 126/286 (48%) + only FDG, 12/286 (4%) + only 68Ga | 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET–CT imaging may be more suitable than 18F-FDG for identifying primary tumors in ECS, while 18F-FDG PET–CT may be more advantageous than 68Ga-DOTA-NOC for patients with suspected metastasis. |

Appendix B

| 18F-FDG (16 Articles) | 68Ga-SSTR (16 Articles) | 68Ga-DOTA-TOC (5 Articles) | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE (7 Articles) | 68Ga-DOTA-NOC (4 Articles) | 68Ga-Pentixafor (1 Article) | 68Ga-CRH (1 Article) | 18F-DOPA (3 Articles) | 11C-Met (1 Article) | 11C-5-HTP (1 Article) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | True + | 46% (75/164) | 59% (109/185) | 65% (17/26) | 49% (29/59) | 62% (51/82) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (3/3) | 32% (7/22) | 100% (2/2) | 100% (1/1) |

| False + | 22% (23/106) | 6% (7/124) | 13% (1/8) | 3% (1/34) | 6% (5/82) | 33% (1/3) | 0% (0/9) * | ||||

| Overt | True + | 54% (47/87) | 74% (73/98) | 70% (7/10) | 70% (29/41) | 77% (30/39) | 100% (3/3) | 35% (7/20) | 100% (2/2) | 100% (1/1) | |

| False + | 60% (3/5) | 3% (2/78) | 20% (1/5) | 3% (1/34) | 0% (0/39) | 33% (1/3) | 0% (0/9) | ||||

| PET | True + | 47% (26/55) | 67% (4/6) | 67% (4/6) | 47% (7/15) | 100% (1/1) | |||||

| False + | 24% (4/17) | 0% (0/2) | |||||||||

| PET–CT | True + | 45% (49/109) | 59% (105/179) | 65% (17/26) | 47% (25/53) | 62% (51/82) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (3/3) | 0% (0/7) | 100% (2/2) | |

| False + | 20% (20/101) | 6% (7/124) | 13% (1/8) | 3% (1/34) | 6% (5/82) | 33% (1/3) | 0% (0/7) | ||||

| De novo | True + | 38% (49/130) | 49% (74/151) | 58% (11/19) | 49% (28/57) | 49% (29/59) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (3/3) | 33% (7/21) | 100% (2/2) | 100% (1/1) |

| False + | 25% (19/75) | 4% (4/101) | 13% (1/8) | 3% (1/34) | 3% (2/59) | 33% (1/3) | 0% (0/2) * | ||||

| Recurrent | True + | 76% (26/34) | 65% (34/52) | 86% (6/7) | 50% (1/2) | 68% (21/31) | 0% (0/1) | ||||

| False + | 12% (4/34) | 10% (3/31) | 10% (3/31) | 0% (0/1) | |||||||

References

- Boscaro, M.; Barzon, L.; Fallo, F.; Sonino, N. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet 2001, 357, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grober, Y.; Grober, H.; Wintermark, M.; Jane, J.A.; Oldfield, E.H. Comparison of MRI techniques for detecting microadenomas in Cushing’s disease. J. Neurosurg. JNS 2018, 128, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invitti, C.; Giraldi, F.P.; De Martin, M.; Cavagnini, F. Diagnosis and Management of Cushing’s Syndrome: Results of an Italian Multicentre Study1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfelder, M.; Nistor, R.; Fahlbusch, R.; Huk, W.J. The accuracy of CT and MR evaluation of the sella turcica for detection of adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting adenomas in Cushing disease. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1993, 14, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arnaldi, G.; Angeli, A.; Atkinson, A.B.; Bertagna, X.; Cavagnini, F.; Chrousos, G.P.; Fava, G.A.; Findling, J.W.; Gaillard, R.C.; Grossman, A.B.; et al. Diagnosis and Complications of Cushing’s Syndrome: A Consensus Statement. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 5593–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.A.; Luciano, M.G.; Doppman, J.L.; Patronas, N.J.; Oldfield, E.H. Pituitary Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Normal Human Volunteers: Occult Adenomas in the General Population. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 120, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, A.D. Sellar susceptibility artifacts: Theory and implications. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1993, 14, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, B.W.; Kucharczyk, W.; Singer, W.; George, S. Pituitary gland MR: A comparative study of healthy volunteers and patients with microadenomas. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1994, 15, 675–679. [Google Scholar]

- Yogi-Morren, D.; Habra, M.A.; Faiman, C.; Bena, J.; Hatipoglu, B.; Kennedy, L.; Weil, R.J.; Hamrahian, A.H. Pituitary mri findings in patients with pituitary and ectopic acth-dependent cushing syndrome: Does a 6-mm pituitary tumor size cut-off value exclude ectopic acth syndrome? Endocr. Pract. 2015, 21, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleseriu, M.; Auchus, R.; Bancos, I.; Ben-Shlomo, A.; Bertherat, J.; Biermasz, N.R.; Boguszewski, C.L.; Bronstein, M.D.; Buchfelder, M.; Carmichael, J.D. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: A guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 847–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.S.; Isidori, A.M.; Wat, W.Z.; Kaltsas, G.A.; Afshar, F.; Sabin, I.; Jenkins, P.J.; Monson, J.P.; Besser, G.M.; Grossman, A.B. Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics of Adrenocorticotropin-Secreting Macroadenomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4963–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katznelson, L.; Bogan, J.S.; Trob, J.R.; Schoenfeld, D.A.; Hedley-Whyte, E.T.; Hsu, D.W.; Zervas, N.T.; Swearingen, B.; Sleeper, M.; Klibanski, A. Biochemical Assessment of Cushing’s Disease in Patients with Corticotroph Macroadenomas1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 1619–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrh, A.; Ospina, N.S.; Nofal, A.; Farah, W.; Barrionuevo, P.; Sarigianni, M.; Mohabbat, A.; Benkhadra, K.; Leon, B.C.; Gionfriddo, M. Predictors of biochemical remission and recurrence after surgical and radiation treatments of Cushing disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B.; Kennedy, A.; Wiggam, M.I.; McCance, D.R.; Sheridan, B. Long-term remission rates after pituitary surgery for Cushing’s disease: The need for long-term surveillance. Clin. Endocrinol. 2005, 63, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, B.M.; Hlavac, M.; Martinez, R.; Buchfelder, M.; Müller, O.A.; Fahlbusch, R. Long-term results after microsurgery for Cushing disease: Experience with 426 primary operations over 35 years. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 108, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandraki, K.I.; Kaltsas, G.A.; Isidori, A.M.; Storr, H.L.; Afshar, F.; Sabin, I.; Akker, S.A.; Chew, S.L.; Drake, W.M.; Monson, J.P. Long-term remission and recurrence rates in Cushing’s disease: Predictive factors in a single-centre study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 168, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashari, W.A.; Gillett, D.; MacFarlane, J.; Powlson, A.S.; Kolias, A.G.; Mannion, R.; Scoffings, D.J.; Mendichovszky, I.A.; Jones, J.; Cheow, H.K.; et al. Modern imaging in Cushing’s disease. Pituitary 2022, 25, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, R.; Gillett, D.; MacFarlane, J.; Van de Meulen, M.; Powlson, A.; Koulouri, O.; Casey, R.; Bashari, W.; Gurnell, M. New types of localization methods for adrenocorticotropic hormone-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 35, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.N.T.; Levivier, M.; Heureux, M.; Wikler, D.; Massager, N.; Devriendt, D.; David, P.; Dumarey, N.; Corvilain, B.; Goldman, S. 11C-methionine PET for the diagnosis and management of recurrent pituitary adenomas. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2006, 33, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.S.; Farhat, R.; Al-Arifi, A.; Al-Kahtani, N.; Kanaan, I.; Abouzied, M. The diagnostic value of fused positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the localization of adrenocorticotropin-secreting pituitary adenoma in Cushing’s disease. Pituitary 2009, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Abe, T.; Watanabe, K. Usefulness of composite methionine–positron emission tomography/3.0-tesla magnetic resonance imaging to detect the localization and extent of early-stage Cushing adenoma: Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. JNS 2010, 112, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, H.; Lee, E.Y.; Choe, E.Y.; Yang, W.I.; Kim, J.Y.; Shin, D.Y.; Cho, H.J.; Kim, T.S.; Yun, M.J.; Lee, J.D. Analysis of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography findings in patients with pituitary lesions. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chittiboina, P.; Montgomery, B.K.; Millo, C.; Herscovitch, P.; Lonser, R.R. High-resolution18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for pituitary adenoma detection in Cushing disease. J. Neurosurg. JNS 2015, 122, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, J.; Patronas, N.J.; Smirniotopoulos, J.; Herscovitch, P.; Dieckman, W.; Millo, C.; Maric, D.; Chatain, G.P.; Hayes, C.P.; Benzo, S.; et al. CRH stimulation improves 18F-FDG-PET detection of pituitary adenomas in Cushing’s disease. Endocrine 2019, 65, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulouri, O.; Steuwe, A.; Gillett, D.; Hoole, A.C.; Powlson, A.S.; Donnelly, N.A.; Burnet, N.G.; Antoun, N.M.; Cheow, H.; Mannion, R.J.; et al. A role for 11C-methionine PET imaging in ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 173, M107–M120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; He, D.; Mao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Utility of 11C-Methionine and 18F-FDG PET/CT in Patients With Functioning Pituitary Adenomas. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, e130–e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, D.; Wang, X.; Du, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. Utility of 13N-Ammonia PET/CT to Detect Pituitary Tissue in Patients with Pituitary Adenomas. Acad. Radiol. 2019, 26, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ju, H.; Zhu, L.; Pan, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Y. Value of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT in localizing the primary lesion in adrenocorticotropic hormone-dependent Cushing syndrome. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2019, 40, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, R.; Gupta, R.; Bhansali, A.; Pivonello, R.; Kumar, R.; Singh, H.; Ahuja, C.; Chhabra, R.; Singh, A.; Dhandapani, S.; et al. Molecular Imaging Targeting Corticotropin-releasing Hormone Receptor for Corticotropinoma: A Changing Paradigm. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 106, 1816–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkmann, S.; Roethlisberger, M.; Mueller, B.; Christ-Crain, M.; Mariani, L.; Nitzsche, E.; Juengling, F. Selective resection of cushing microadenoma guided by preoperative hybrid 18-fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine and 11-C-methionine PET/MRI. Pituitary 2021, 24, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novruzov, F.; Aliyev, A.; Wan, M.Y.S.; Syed, R.; Mehdi, E.; Aliyeva, I.; Giammarile, F.; Bomanji, J.B.; Kayani, I. The value of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TATE PET/CT in diagnosis and management of suspected pituitary tumors. Eur. J. Hybrid Imaging 2021, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Tong, A.; Hacker, M.; Feng, M.; Huo, L.; Li, X. Usefulness of 68Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT on Diagnosis and Management of Cushing Syndrome. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 47, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidori, A.M.; Kaltsas, G.A.; Mohammed, S.; Morris, D.G.; Jenkins, P.; Chew, S.L.; Monson, J.P.; Besser, G.M.; Grossman, A.B. Discriminatory Value of the Low-Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test in Establishing the Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Cushing’s Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 5299–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriere, A.; Tabarin, A. Biochemical testing to differentiate Cushing’s disease from ectopic ACTH syndrome. Pituitary 2022, 25, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frete, C.; Corcuff, J.-B.; Kuhn, E.; Salenave, S.; Gaye, D.; Young, J.; Chanson, P.; Tabarin, A. Non-invasive diagnostic strategy in ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 3273–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldi, F.P.; Cavallo, L.M.; Tortora, F.; Pivonello, R.; Colao, A.; Cappabianca, P.; Mantero, F. The role of inferior petrosal sinus sampling in ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome: Review and joint opinion statement by members of the Italian Society for Endocrinology, Italian Society for Neurosurgery, and Italian Society for Neuroradiology. Neurosurg. Focus FOC 2015, 38, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetti, B.; Grossrubatscher, E.; Dalino Ciaramella, P.; Boccardi, E.; Loli, P. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling. Endocr. Connect. 2016, 5, R12–R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, J.E.; Johnston, P.C.; Hui, F.; Mulligan, G.; Weil, R.J.; Recinos, P.F.; Yogi-Morren, D.; Salvatori, R.; Mukherjee, D.; Gallia, G.; et al. Pitfalls in Performing and Interpreting Inferior Petrosal Sinus Sampling: Personal Experience and Literature Review. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e1953–e1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, H.J.; Kang, S.; Seo, J.-H.; Chun, K.A.; Cho, I.H.; Won, K.S.; Zeon, S.K.; Ahn, B.-C.; et al. Incidental pituitary uptake on whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT: A multicentre study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 2334–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, K.-H.; Choe, Y.S.; Kim, B.-T. Incidental Focal 18F-FDG Uptake in the Pituitary Gland: Clinical Significance and Differential Diagnostic Criteria. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomura, N.; Saginoya, T.; Mizuno, Y.; Goto, H. Accumulation of (11)C-methionine in the normal pituitary gland on (11)C-methionine PET. Acta Radiol 2017, 58, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergström, M.; Muhr, C.; Lundberg, P.; Långström, B. PET as a tool in the clinical evaluation of pituitary adenomas. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 1991, 32, 610–615. [Google Scholar]

- Garmes, H.M.; Carvalheira, J.B.C.; Reis, F.; Queiroz, L.S.; Fabbro, M.D.; Souza, V.F.P.; Santos, A.O. Pituitary carcinoma: A case report and discussion of potential value of combined use of Ga-68 DOTATATE and F-18 FDG PET/CT scan to better choose therapy. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2017, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiangsong, Z.; Dianchao, Y.; Anwu, T. Dynamic 13N-ammonia PET: A new imaging method to diagnose hypopituitarism. J. Nucl. Med. 2005, 46, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ejaz, S.; Vassilopoulou-Sellin, R.; Busaidy, N.L.; Hu, M.I.; Waguespack, S.G.; Jimenez, C.; Ying, A.K.; Cabanillas, M.; Abbara, M.; Habra, M.A. Cushing syndrome secondary to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion. Cancer 2011, 117, 4381–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deldycke, A.; Haenebalcke, C.; Taes, Y. Paraneoplastic Cushing syndrome, case-series and review of the literature. Acta Clin. Belg. 2018, 73, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddaert, G.; Grand, B.; Le Pimpec-Barthes, F.; Cazes, A.; Bertagna, X.; Riquet, M. Bronchial Carcinoid Tumors Causing Cushing’s Syndrome: More Aggressive Behavior and the Need for Early Diagnosis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 94, 1823–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacak, K.; Ilias, I.; Chen, C.C.; Carrasquillo, J.A.; Whatley, M.; Nieman, L.K. The Role of [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography and [111In]-Diethylenetriaminepentaacetate-d-Phe-Pentetreotide Scintigraphy in the Localization of Ectopic Adrenocorticotropin-Secreting Tumors Causing Cushing’s Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhai, G.; Zhang, M.; Ning, G.; Li, B. The role of integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT in identification of ectopic ACTH secretion tumors. Endocrine 2009, 36, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, M.; Sugiyama, T.; Izumiyama, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Hirata, Y. Clinical features and management of ectopic ACTH syndrome at a single institute in Japan. Endocr. J. 2010, 57, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisser, L.; Kulterer, O.C.; Itariu, B.; Fueger, B.; Weber, M.; Mazal, P.; Vraka, C.; Pichler, V.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Hacker, M.; et al. Diagnostic Role of PET/CT Tracers in the Detection and Localization of Tumours Responsible for Ectopic Cushing’s Syndrome. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 2477–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.; Garrigue, P.; Dahan, L.; Castinetti, F.; Sebag, F.; Baumstark, K.; Archange, C.; Jha, A.; Pacak, K.; Guillet, B.; et al. Prospective evaluation of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in limited disease neuroendocrine tumours and/or elevated serum neuroendocrine biomarkers. Clin. Endocrinol. 2018, 89, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Spring, M.; Carroll, P.V.; Barrington, S.F.; Powrie, J.K. 18Flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the localization of ectopic ACTH-secreting neuroendocrine tumours. Clin. Endocrinol. 2006, 64, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A.B.; Taboada, G.F.; Carneiro, M.P.; Neto, L.V.; Wildemberg, L.E.A.; Madi, K.; Domingues, R.C.; Gadelha, M.R. Utility of [18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography in the localization of ectopic ACTH-secreting tumors. Pituitary 2008, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakade, H.R.; Kasaliwal, R.; Jagtap, V.S.; Bukan, A.; Budyal, S.R.; Khare, S.; Lila, A.R.; Bandgar, T.; Menon, P.S.; Shah, N.S. Ectopic ACTH-secreting syndrome: A single-center experience. Endocr. Pract. 2013, 19, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, F.; Cheng, X. Use of 18F-FDG PET/CT to Differentiate Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone-Secreting Lung Tumors From Tumor-Like Pulmonary Infections in Patients With Ectopic Cushing Syndrome. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 762327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; He, Q.; Long, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Comparison of diagnostic efficacy of (18)F-FDG PET/CT and (68)Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT in ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Front Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 962800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, L.; Colandrea, M.; Fracassi, S.L.; Sansovini, M.; Paganelli, G. 68Ga- DOTA0-Tyr3octreotide (DOTATOC) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT in five cases of ectopic adrenocorticotropin-secreting tumours. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 81, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkitaraman, B.; Karunanithi, S.; Kumar, A.; Bal, C.; Ammini, A.C.; Kumar, R. 68Ga-DOTATOC PET-CT in the localization of source of ectopic ACTH in patients with ectopic ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Clin. Imaging 2014, 38, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannachalee, T.; Turcu, A.F.; Bancos, I.; Habra, M.A.; Avram, A.M.; Chuang, H.H.; Waguespack, S.G.; Auchus, R.J. The Clinical Impact of [68Ga]-DOTATATE PET/CT for the Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone-Secreting Tumours. Clin. Endocrinol. 2019, 91, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélissant Benesty, O.; Nataf, V.; Ohnona, J.; Michaud, L.; Zhang-Yin, J.; Bertherat, J.; Chanson, P.; Reznik, Y.; Talbot, J.-N.; Montravers, F. 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in detecting neuroendocrine tumours responsible for initial or recurrent paraneoplastic Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrine 2020, 67, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkan, Z.G.; Kuyumcu, S.; Balköse, D.; Özkan, B.; Aksakal, N.; Yılmaz, E.; Şanlı, Y.; Türkmen, C.; Aral, F.; Adalet, I. The value of somatostatin receptor imaging with In-111 octreotide and/or Ga-68 DOTATATE in localizing ectopic ACTH producing tumors. Mol. Imaging Radionucl. Ther. 2013, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goroshi, M.R.; Jadhav, S.S.; Lila, A.R.; Kasaliwal, R.; Khare, S.; Yerawar, C.G.; Hira, P.; Phadke, U.; Shah, H.; Lele, V.R.; et al. Comparison of 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and contrast-enhanced CT in localisation of tumours in ectopic ACTH syndrome. Endocr. Connect. 2016, 5, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccato, F.; Cecchin, D.; Gregianin, M.; Ricci, G.; Campi, C.; Crimì, F.; Bergamo, M.; Versari, A.; Lacognata, C.; Rea, F.; et al. The role of 68Ga-DOTA derivatives PET-CT in patients with ectopic ACTH syndrome. Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamov, E.; Hinojosa-Amaya, J.M.; Stack, M.; Fleseriu, M. Diagnostic utility of Gallium-68-somatostatin receptor PET/CT in ectopic ACTH-secreting tumors: A systematic literature review and single-center clinical experience. Pituitary 2019, 22, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Kumar, A.; Julka, P.K.; Mathur, S.R.; Kaushal, S.; Kumar, R.; Jindal, T.; Suri, V. Thymic neuroendocrine tumour (carcinoid): Clinicopathological features of four patients with different presentation. Interact. CardioVascular Thorac. Surg. 2010, 11, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashari, W.A.; Senanayake, R.; MacFarlane, J.; Gillett, D.; Powlson, A.S.; Kolias, A.; Mannion, R.J.; Koulouri, O.; Gurnell, M. Using Molecular Imaging to Enhance Decision Making in the Management of Pituitary Adenomas. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 57S–62S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemskova, M.S.; Gundabolu, B.; Sinaii, N.; Chen, C.C.; Carrasquillo, J.A.; Whatley, M.; Chowdhury, I.; Gharib, A.M.; Nieman, L.K. Utility of Various Functional and Anatomic Imaging Modalities for Detection of Ectopic Adrenocorticotropin-Secreting Tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, J.; Ekman, B. Atypical or typical adrenocorticotropic hormone-producing pulmonary carcinoids and the usefulness of 11C-5-hydroxytryptophan positron emission tomography: Two case reports. J. Med. Case Rep. 2013, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiadis, A.S.; Papadakis, G.Z.; Biro, J.; Keil, M.F.; Lyssikatos, C.; Quezado, M.M.; Merino, M.; Schrump, D.S.; Kebebew, E.; Patronas, N.J.; et al. Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone and Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Co-Secreting Tumors in Children and Adolescents Causing Cushing Syndrome: A Diagnostic Dilemma and How to Solve It. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyakumar, S.; Paul, T.V.; Asha, H.S.; Gnanamuthu, B.R.; Paul, M.; Abraham, D.T.; Rajaratnam, S.; Thomas, N. Ectopic Cushing syndrome: A 10-year experience from a tertiary care center in Southern India. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 18F-FDG (8 Articles) | 18F-FDG + CRH (1 Article) | 18F-FET (1 Article) | 11C-Met (5 Articles) | 68Ga-DOTA-TATE (1 Article) | 68Ga-Pentixafor (1 Article) | 68Ga-DOTA-CRH (1 Article) | 13N-Ammonia (1 Article) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | True + | 49% (47/96) | 56% (15/27) | 100% (9/9) | 87% (53/61) | 100% (7/7) | 86% (6/7) | 100% (24/24) | 90% (9/10) |

| False − | 51% (49/96) | 44% (12/27) | 0% (0/9) | 10% (6/61) | 0% (0/7) | 14% (1/7) | 0% (0/24) | 10% (1/10) | |

| False + | 0% (0/96) | 0% (0/27) | 0% (0/9) | 3% (2/61) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/10) | |

| Histological confirmation | True + | 52% (45/87) | 56% (15/27) | 100% (9/9) | 85% (45/53) | 100% (7/7) | 100% (24/24) | 90% (9/10) | |

| False - | 48% (42/87) | 44% (12/27) | 0% (0/9) | 11% (6/53) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/24) | 10% (1/10) | ||

| False + | 0% (0/87) | 0% (0/27) | 0% (0/9) | 4% (2/53) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/10) | ||

| De novo | True + | 56% (44/79) | 61% (14/23) | 88% (28/32) | 100% (4/4) | 100% (24/24) | 88% (7/8) | ||

| False - | 44% (35/79) | 39% (9/23) | 10% (3/32) | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/24) | 13% (1/8) | |||

| False + | 0% (0/79) | 0% (0/23) | 3% (1/32) | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/8) | |||

| Recurrent | True + | 35% (6/17) | 50% (2/4) | 85% (17/20) | 100% (7/7) | 68% (2/3) | 100% (2/2) | ||

| False - | 65 (11/17) | 50% (2/4) | 15% (3/20) | 0% (0/7) | 33% (1/3) | 0% (0/2) | |||

| False + | 0% (0/17) | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/32) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/3) | 0% (0/2) | |||

| MRI negative/inconclusive | True + | 17% (4/23) | 22% (2/9) | 67% (8/12) | 67% (2/3) | 100% (4/4) | 0% (0/1) | ||

| False - | 83% (19/23) | 7/9 (78%) | 25% (3/12) | 33% (1/3) | 0% (0/4) | 100% (1/1) | |||

| False + | 0% (0/23) | 0% (0/9) | 8% (1/12) | 0% (0/3) | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/1) | |||

| Micro-adenoma (unspecified) | True + | 75% (9/12) | 100% (9/9) | 94% (16/17) | 86% (6/7) | ||||

| False - | 25% (3/12) | 0 (0/9) | 0% (0/17) | 14% (1/7) | |||||

| False + | 0% (0/12) | 0 (0/9) | 6% (1/17) | 0% (0/7) | |||||

| ≤6 mm | True + | 45% (10/22) | 57% (4/7) | 83% (5/6) | 100% (10/10) | 100% (3/3) | |||

| False - | 55% (12/22) | 43% (3/7) | 0% (0/6) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/3) | ||||

| False + | 0% (0/22) | 0% (0/9) | 17% (1/6) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/3) | ||||

| 7–9 mm | True + | 82% (9/11) | 100% (3/3) | 100% (5/5) | 100% (7/7) | 100% (2/2) | |||

| False - | 18% (2/11) | 0% (0/3) | 0% (0/5) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/2) | ||||

| False + | 0% (0/11) | 0% (0/3) | 0% (0/5) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/2) | ||||

| ≥10 mm | True + | 62% (16/26) | 88% (7/8) | 100% (7/7) | 100% (7/7) | 80% (4/5) | |||

| False - | 38% (10/26) | 13% (1/8) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/7) | 20% (1/5) | ||||

| False + | 0% (0/26) | 0% (0/8) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/5) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slagboom, T.N.A.; Stenvers, D.J.; van de Giessen, E.; Roosendaal, S.D.; de Win, M.M.L.; Bot, J.C.J.; Aronica, E.; Post, R.; Hoogmoed, J.; Drent, M.L.; et al. Continuing Challenges in the Definitive Diagnosis of Cushing’s Disease: A Structured Review Focusing on Molecular Imaging and a Proposal for Diagnostic Work-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082919

Slagboom TNA, Stenvers DJ, van de Giessen E, Roosendaal SD, de Win MML, Bot JCJ, Aronica E, Post R, Hoogmoed J, Drent ML, et al. Continuing Challenges in the Definitive Diagnosis of Cushing’s Disease: A Structured Review Focusing on Molecular Imaging and a Proposal for Diagnostic Work-Up. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(8):2919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082919

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlagboom, Tessa N. A., Dirk Jan Stenvers, Elsmarieke van de Giessen, Stefan D. Roosendaal, Maartje M. L. de Win, Joseph C. J. Bot, Eleonora Aronica, René Post, Jantien Hoogmoed, Madeleine L. Drent, and et al. 2023. "Continuing Challenges in the Definitive Diagnosis of Cushing’s Disease: A Structured Review Focusing on Molecular Imaging and a Proposal for Diagnostic Work-Up" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 8: 2919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082919

APA StyleSlagboom, T. N. A., Stenvers, D. J., van de Giessen, E., Roosendaal, S. D., de Win, M. M. L., Bot, J. C. J., Aronica, E., Post, R., Hoogmoed, J., Drent, M. L., & Pereira, A. M. (2023). Continuing Challenges in the Definitive Diagnosis of Cushing’s Disease: A Structured Review Focusing on Molecular Imaging and a Proposal for Diagnostic Work-Up. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(8), 2919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082919