Examining Clinical Opinion and Experience Regarding Utilization of Plain Radiography of the Spine: Evidence from Surveying the Chiropractic Profession

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Distribution

2.2. Statistical Analyses

2.2.1. Procedures and Sample

2.2.2. Dependent Variable

- (1)

- I do NOT take radiographs in my clinic, I refer patients out to another facility (coded as 0);

- (2)

- I DO have an X-ray machine in my practice, but I still refer patients out to another facility for the majority of my spinal radiographs (coded as 0);

- (3)

- I have a plain film X-ray system in my practice and use it for the majority of my radiographs (coded as 1);

- (4)

- I have a DR (digital radiography) digital X-ray system in my practice and use it for the majority of my radiographs (coded as 1);

- (5)

- I have a CR (computed radiography) digital X-ray system in my practice and use it for the majority of my radiographs (coded as 1).

2.2.3. Predictors

2.3. Clinician Opinion & Experience on Chiropractic Radiography (COECR) Scale

2.4. Analytic Plan

2.5. Study 1: Predicting the Use of Plain Radiography of the Spine in Chiropractic Practice

2.6. Study 2: COECR Scale Development and Validation

Rasch Model

3. Results

3.1. Initial Results

3.2. Descriptive Statistics, Chi-Square, and Mean Differences

3.3. Study 1: Logistic Regression

- (1)

- radiographic procedures in a chiropractic office have value beyond the identification of pathology, OR = 1.54, p < 0.05

- (2)

- radiographs for biomechanical procedures have significant value, OR = 1.72, p < 0.01

- (3)

- radiographic procedures are vital to chiropractic care, OR = 5.93, p < 0.01

- (4)

- radiographic procedures aid in the measurement of clinical outcomes, OR = 2.23, p < 0.01

- (5)

- that sharing chiropractic clinical findings from radiographic studies with the patient is beneficial to their clinical outcome, OR = 1.18, p < 0.05

- (6)

- biomechanical analysis or measurements of spinal alignment are valid reasons for obtaining spinal radiograph, OR = 1.4, p < 0.05

- (7)

- and care plan modification consideration is a valid reason to obtain a spinal radiograph, OR = 1.57, p < 0.01.

3.4. Study 2: Scale Construction

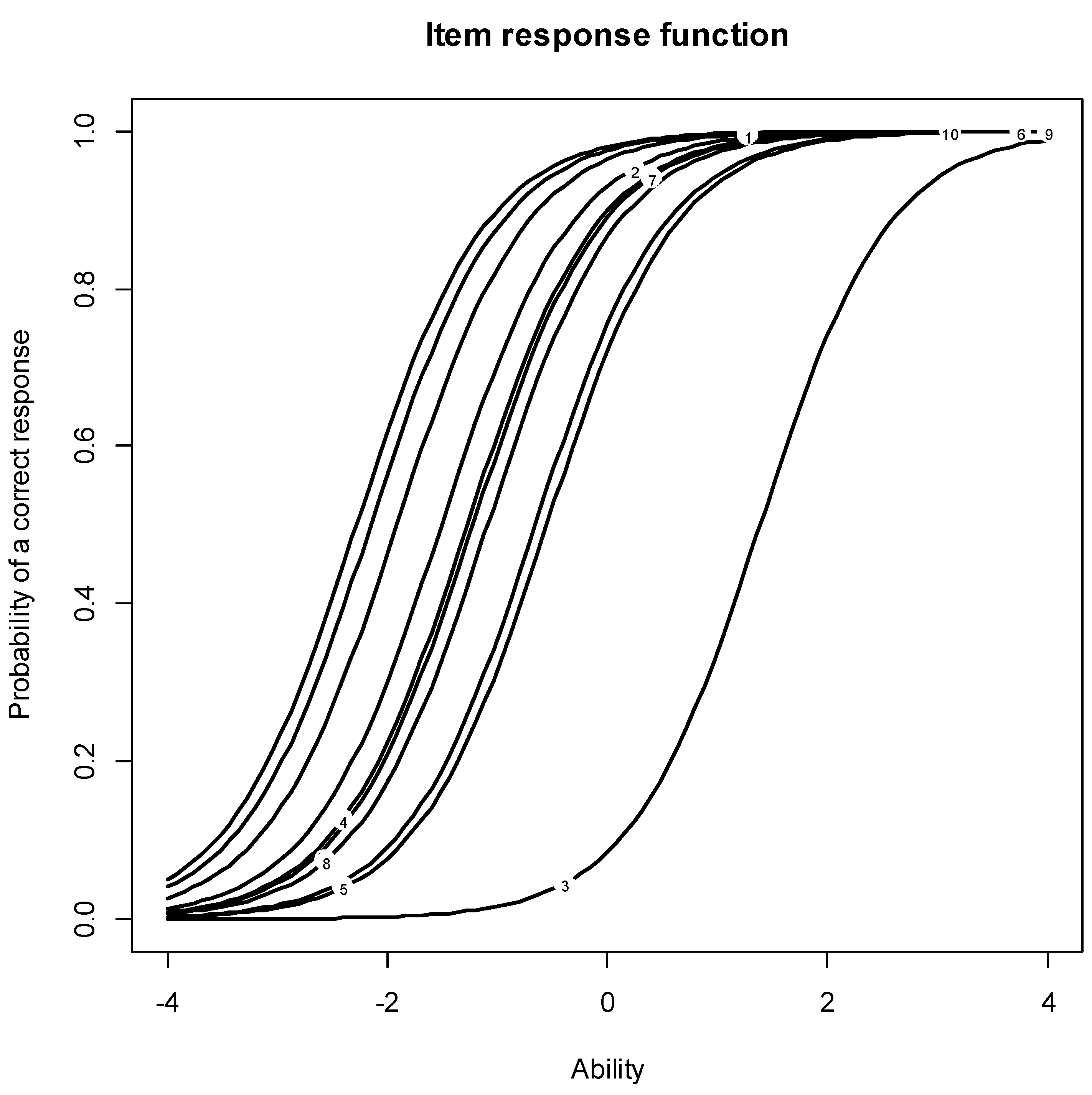

3.5. Item Response Theory

3.6. Results Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Other Findings

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

- Invitation to complete the Survey

- Chiropractic Radiology Evidence-Based Practice Survey

Appendix B

| State | N | % |

| AL | 352 | 0.72% |

| AK | 146 | 0.29% |

| AZ | 1032 | 2.07% |

| AR | 478 | 0.96% |

| CA | 7617 | 15.31% |

| CO | 1304 | 2.62% |

| CT | 716 | 1.44% |

| DE | 81 | 0.16% |

| DC | 30 | 0.06% |

| FL | 4346 | 8.74% |

| GA | 1447 | 2.90% |

| HI | 63 | 0.13% |

| ID | 399 | 0.80% |

| IL | 2656 | 5.34% |

| IN | 465 | 0.93% |

| IA | 718 | 1.44% |

| KS | 393 | 0.79% |

| KY | 722 | 1.45% |

| LA | 340 | 0.68% |

| MA | 667 | 1.34% |

| MD | 375 | 0.75% |

| ME | 134 | 0.27% |

| MI | 1823 | 3.66% |

| MN | 1010 | 2.03% |

| MS | 264 | 0.53% |

| MO | 1107 | 2.23% |

| MT | 172 | 0.35% |

| NE | 610 | 1.23% |

| NV | 315 | 0.63% |

| NH | 188 | 0.38% |

| NJ | 2455 | 4.93% |

| NM | 179 | 0.36% |

| NY | 3462 | 6.96% |

| NC | 864 | 1.74% |

| ND | 133 | 0.27% |

| OH | 2153 | 4.33% |

| OK | 355 | 0.71% |

| OR | 654 | 1.31% |

| PA | 1998 | 4.02% |

| RI | 80 | 0.16% |

| SC | 616 | 1.24% |

| SD | 158 | 0.32% |

| TN | 557 | 1.12% |

| TX | 2657 | 5.34% |

| UT | 519 | 1.04% |

| VT | 97 | 0.19% |

| VA | 601 | 1.21% |

| WA | 1200 | 2.41% |

| WV | 108 | 0.22% |

| WI | 869 | 1.75% |

| WY | 62 | 0.42% |

| Total | 49,747 | 100.00% |

Appendix C

| State | n | % |

| AL | 16 | 0.44% |

| AK | 14 | 0.38% |

| AZ | 51 | 1.40% |

| AR | 16 | 0.44% |

| CA | 423 | 11.62% |

| CO | 89 | 2.44% |

| CT | 27 | 0.74% |

| DE | 3 | 0.08% |

| DC | 5 | 0.14% |

| FL | 198 | 5.44% |

| GA | 199 | 5.47% |

| HI | 8 | 0.22% |

| ID | 59 | 1.62% |

| IL | 159 | 4.37% |

| IN | 89 | 2.44% |

| IA | 77 | 2.11% |

| KS | 31 | 0.85% |

| KY | 13 | 0.36% |

| LA | 84 | 2.30% |

| MA | 41 | 1.13% |

| MD | 47 | 1.29% |

| ME | 8 | 0.22% |

| MI | 259 | 7.11% |

| MN | 73 | 2.00% |

| MS | 5 | 0.14% |

| MO | 38 | 1.04% |

| MT | 25 | 0.69% |

| NE | 26 | 0.71% |

| NV | 43 | 1.18% |

| NH | 13 | 0.36% |

| NJ | 87 | 2.39% |

| NM | 19 | 0.52% |

| NY | 108 | 2.97% |

| NC | 71 | 1.95% |

| ND | 13 | 0.36% |

| OH | 104 | 2.86% |

| OK | 23 | 0.63% |

| OR | 164 | 4.50% |

| PA | 192 | 5.27% |

| RI | 7 | 0.19% |

| SC | 59 | 1.62% |

| SD | 52 | 1.42% |

| TN | 37 | 1.02% |

| TX | 121 | 3.32% |

| UT | 126 | 3.46% |

| VT | 6 | 0.16% |

| VA | 69 | 1.89% |

| WA | 152 | 4.17% |

| WV | 6 | 0.16% |

| WI | 68 | 1.87% |

| WY | 18 | 0.49% |

| Total | 3641 | 100.00% |

Appendix D

- 41% were short comments emphasizing the need for X-rays as an integral and essential tool within their chiropractic practice.

- 37% commented on the differences between utilization in a chiropractic clinical setting versus a medical setting.

- 37% described conditions that they found on numerous occasions in which the patient had no red flags or complaints yet required alteration of care.

- 5% of the comments were related to clinicians supporting the need for this type of survey.

- 4% revolved around comments related to safety.

- Less than 1% commented on question selection.

References

- Koch, C.; Hänsel, F. Non-specific Low Back Pain and Postural Control During Quiet Standing—A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, J.D.; Boyle, E.; Côté, P.; Hogg-Johnson, S.; Bondy, S.J.; Haldeman, S. Risk of Carotid Stroke after Chiropractic Care: A Population-Based Case-Crossover Study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2017, 26, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, A.J.; Carroll, M.T.; Robinson, A.; Mitchell, E.K.L. Adverse Events Due to Chiropractic and Other Manual Therapies for Infants and Children: A Review of the Literature. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2015, 38, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, S.M.; de Zoete, A.; van Middelkoop, M.; Assendelft, W.J.J.; de Boer, M.R.; van Tulder, M.W. Benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy for the treatment of chronic low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2019, 364, l689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.L.; Smith, M. Association Between Chiropractic Utilization and Opioid Prescriptions Among People With Back or Neck Pain: Evaluation of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2022, 45, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, M.; Chopra, D.; Smith, A.M.; Fritz, J.M.; Martin, B.C. Associations Between Early Chiropractic Care and Physical Therapy on Subsequent Opioid Use Among Persons With Low Back Pain in Arkansas. J. Chiropr. Med. 2022, 21, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emary, P.C.; Brown, A.L.; Oremus, M.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Cameron, D.F.; DiDonato, J.; Busse, J.W. Association of Chiropractic Care With Receiving an Opioid Prescription for Noncancer Spinal Pain Within a Canadian Community Health Center: A Mixed Methods Analysis. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2022, 45, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whedon, J.M.; Uptmor, S.; Toler, A.W.J.; Bezdjian, S.; MacKenzie, T.A.; Kazal, L.A. Association between chiropractic care and use of prescription opioids among older medicare beneficiaries with spinal pain: A retrospective observational study. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2022, 30, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeney, B.J.; Fulton-Kehoe, D.; Turner, J.A.; Wickizer, T.M.; Chan, K.C.G.; Franklin, G.M. Early predictors of lumbar spine surgery after occupational back injury: Results from a prospective study of workers in Washington State. Spine 2013, 38, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trager, R.J.; Daniels, C.J.; Perez, J.A.; Casselberry, R.M.; Dusek, J.A. Association between chiropractic spinal manipulation and lumbar discectomy in adults with lumbar disc herniation and radiculopathy: Retrospective cohort study using United States’ data. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e068262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goertz, C.M.; Long, C.R.; Vining, R.D.; Pohlman, K.A.; Walter, J.; Coulter, I. Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical Care Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members With Low Back Pain: A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Wang, D.; Lea, R.; Murphy, D. Chiropractic Care for Workers with Low Back Pain. Work. Compens. Res. Inst. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes, M.; Willetts, J.; Wasiak, R. Health maintenance care in work-related low back pain and its association with disability recurrence. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndetan, H.; Hawk, C.; Evans, W.; Tanue, T.; Singh, K. Chiropractic Care for Spine Conditions: Analysis of National Health Interview Survey. J. Health Care Res. 2020, 1, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.J. Historical influence on the practice of chiropractic radiology: Part II—Thematic analysis on the opinions of diplomates of the American Chiropractic College of Radiology about the future. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2017, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. The Chiropractic Scope of Practice in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2014, 37, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Betz, J.W.; Harrison, D.E.; Siskin, L.A.; Hirsh, D.W.; International Chiropractors Association Rapid Response Research Review Subcommittee. Radiophobia Overreaction: College of Chiropractors of British Columbia Revoke Full X-Ray Rights Based on Flawed Study and Radiation Fear-Mongering. Dose-Response Publ. Int. Hormesis Soc. 2021, 19, 15593258211033142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbreras, B.; Donat, L.; Hernández-Aguado, I. Incidental findings in imaging diagnostic tests: A systematic review. Br. J. Radiol. 2010, 83, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammendolia, C.; Côté, P.; Hogg-Johnson, S.; Bombardier, C. Do Chiropractors Adhere to Guidelines for Back Radiographs?: A Study of Chiropractic Teaching Clinics in Canada. Spine 2007, 32, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Imaging studies in patients with spinal pain: Practice audit evaluation of Choosing Wisely Canada recommendations. Can. Fam. Physician 2016, 62, e129–e137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Zucker, M.I. Validity of a Set of Clinical Criteria to Rule Out Injury to the Cervical Spine in Patients with Blunt Trauma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, J.J.; Ulsh, B.A. It Is Time to Move Beyond the Linear No-Threshold Theory for Low-Dose Radiation Protection. Dose-Response 2018, 16, 155932581877965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollycove, M.; Feinendegen, L.E. Molecular biology, epidemiology, and the demise of the linear no-threshold (LNT) hypothesis. Comptes Rendus Académie Sci. Ser. III Sci. Vie 1999, 322, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.A.; Pennington, C.W.; Sacks, B. Subjecting Radiologic Imaging to the Linear No-Threshold Hypothesis: A Non Sequitur of Non-Trivial Proportion. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubiana, M.; Feinendegen, L.E.; Yang, C.; Kaminski, J.M. The Linear No-Threshold Relationship Is Inconsistent with Radiation Biologic and Experimental Data. Radiology 2009, 251, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.A.; Welsh, J.S. Does Imaging Technology Cause Cancer? Debunking the Linear No-Threshold Model of Radiation Carcinogenesis. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 15, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orton, C.G.; Williamson, J.F. Controversies in Medical Physics: A Compendium of Point/Counterpoint Debates Volume 3; American Association of Physicists in Medicine: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2017; 349p. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ACA-Choosing-Wisely-List.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- II) Chiropractic Guideline for Spine Radiography for the Assessment of Spinal Subluxation in Children and Adults. Pract. Chiropr. Comm. Radiol. Protoc. 2006. Available online: http://www.pccrp.org/docs/PCCRP%20Section%20II.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Guyatt, G.H. Evidence-based medicine. ACP J. Club 1991, 114, A-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Zimring, C.; Zhu, X.; DuBose, J.; Seo, H.-B.; Choi, Y.-S.; Quan, X.; Joseph, A. A Review of the Research Literature on Evidence-Based Healthcare Design. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2008, 1, 61–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, K.; Bhargava, D. Evidence Based Health Care: A scientific approach to health care. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2007, 7, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, R.B.; Devereaux, P.J.; Guyatt, G.H. Physicians’ and patients’ choices in evidence based practice. BMJ 2002, 324, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2020—NBCE Survey Analysis. Available online: https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Gliedt, J.A.; Perle, S.M.; Puhl, A.A.; Daehler, S.; Schneider, M.J.; Stevans, J. Evaluation of United States chiropractic professional subgroups: A survey of randomly sampled chiropractors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.J. Historical influence on the practice of chiropractic radiology: Part I—A survey of Diplomates of the American Chiropractic College of Radiology. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2017, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-13-479054-1. [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden, W.J.; Hambleton, R.K. (Eds.) Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-1-4419-2849-8. [Google Scholar]

- Reise, S.P.; Widaman, K.F.; Pugh, R.H. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reise, S.P.; Revicki, D.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Item Response Theory Modeling: Applications to Typical Performance Assessment; Multivariate Applications Series; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-84872-972-8. [Google Scholar]

- Faraway, J.J. Generalized linear models. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Peterson, P., Baker, E., McGaw, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 178–183. ISBN 978-0-08-044894-7. [Google Scholar]

- Midi, H.; Sarkar, S.K.; Rana, S. Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2010, 13, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017.

- Rasch, G. An Item Analysis Which Takes Individual Differences into Account. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1966, 19, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toit, M.D. IRT from SSI: BILOG-MG, MULTILOG, PARSCALE, TESTFACT; Scientific Software International: Skokie, IL, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-89498-053-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tranmer, M.; Murphy, J.; Elliot, M.; Pampaka, M. Multiple Linear Regression, 2nd ed.; Cathie Marsh Institute: Manchester, UK, 2020; 59p. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus User’s Guide, 6th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lawley, D.N. VI.—The Estimation of Factor Loadings by the Method of Maximum Likelihood. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. 1940, 60, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, F.M.; Novick, M.R.; Birnbaum, A. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores; Addison-Wesley: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R.K.; Swaminathan, H. Item Response Theory: Principles and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F. Latent Structure Analysis [by] Paul F. Lazarsfeld [and] Neil W. Henry; Houghton, Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.R. Testing the Local Independence Assumption in Item Response Theory. ETS Res. Rep. Ser. 1984, 1984, i-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.M. Effects of local item dependence on the fit and equating performance of the three-parameter logistic model. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1984, 8, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.M. Scaling Performance Assessments: Strategies for Managing Local Item Dependence. J. Educ. Meas. 1993, 30, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.B.; Makransky, G.; Horton, M. Critical Values for Yen’s Q3: Identification of Local Dependence in the Rasch Model Using Residual Correlations. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2017, 41, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, P.; Hatzinger, R. CML based estimation of extended Rasch models with the eRm package in R. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 49, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, R.P. mirt: A multidimensional item response theory package for the R environment. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P.D. Missing Data; SAGE Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-4522-0790-2. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; 394p. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Skokie, IL, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-89498-033-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.N.; Wright, B.D. A Model for Partial Credit Scoring; Statistical Laboratory, Department of Education, University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H.J.; Downie, A.S.; Moore, C.S.; French, S.D. Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession: A narrative review. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2018, 26, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.; Cancelliere, C.; Mior, S.; Kumar, V.; Smith, A.; Côté, P. The clinical utility of routine spinal radiographs by chiropractors: A rapid review of the literature. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2020, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. Critical analysis of “X-ray imaging is essential for contemporary chiropractic and manual therapy spinal rehabilitation: Radiography increases benefits and reduces risks” by Oakley et al. Dose-Response 2018, 16, 1559325818813509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawchuk, G.; Goertz, C.; Axén, I.; Descarreaux, M.; French, S.; Haas, M.; Hartvigsen, J.; Kolberg, C.; Jenkins, H.; Peterson, C.; et al. Letter to the Editor Re: Oakley PA, Cuttler JM, Harrison DE. X-Ray Imaging Is Essential for Contemporary Chiropractic and Manual Therapy Spinal Rehabilitation: Radiography Increases Benefits and Reduces Risks. Dose-Response 2018, 16, 1559325818811521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Radiophobic Fear-Mongering, Misappropriation of Medical References and Dismissing Relevant Data Forms the False Stance for Advocating Against the Use of Routine and Repeat Radiography in Chiropractic and Manual Therapy. Dose-Response Publ. Int. Hormesis Soc. 2021, 19, 1559325820984626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Death of the ALARA Radiation Protection Principle as Used in the Medical Sector. Dose-Response 2020, 18, 1559325820921641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, T.M. Evidence-Based Nursing Practice: To Infinity and Beyond. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2003, 34, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, D.L. Evidence-based medicine and treatment choices. The Lancet 1997, 349, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakoshi, N.; Itoi, E.; Kobayashi, M.; Kodama, H. Impact of postural deformities and spinal mobility on quality of life in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2003, 14, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebo, B.G.; Oren, J.H.; Challier, V.; Lafage, R.; Ferrero, E.; Liu, S.; Vira, S.; Spiegel, M.A.; Harris, B.Y.; Liabaud, B.; et al. Global sagittal axis: A step toward full-body assessment of sagittal plane deformity in the human body. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 25, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Okamoto, M.; Hatsushikano, S.; Shimoda, H.; Ono, M.; Watanabe, K. Normative values of spino-pelvic sagittal alignment, balance, age, and health-related quality of life in a cohort of healthy adult subjects. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2016, 25, 3675–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac-Thiong, J.-M.; Transfeldt, E.E.; Mehbod, A.A.; Perra, J.H.; Denis, F.; Garvey, T.A.; Lonstein, J.E.; Wu, C.; Dorman, C.W.; Winter, R.B. Can c7 plumbline and gravity line predict health related quality of life in adult scoliosis? Spine 2009, 34, E519–E527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Cailliet, R.; Harrison, D.D.; Troyanovich, S.J.; Harrison, S.O. A review of biomechanics of the central nervous system--Part I: Spinal canal deformations resulting from changes in posture. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1999, 22, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, C.; Massicotte, E.M.; Fehlings, M.G.; Shamji, M.F. Association of preoperative cervical spine alignment with spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging hyperintensity and myelopathy severity: Analysis of a series of 124 cases. Spine 2015, 40, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, H.-W.; Wang, J.-J.; Xun, L.; Fu, N.-X.; Huang, H. Diagnostic Value of T1 Slope in Degenerative Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Son, E.-S.; Seo, E.-M.; Suk, K.-S.; Kim, K.-T. Factors determining cervical spine sagittal balance in asymptomatic adults: Correlation with spinopelvic balance and thoracic inlet alignment. Spine J. Off. J. North Am. Spine Soc. 2015, 15, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Ha, J.-K.; Chung, J.-H.; Hwang, C.J.; Lee, C.S.; Cho, J.H. A retrospective study to reveal the effect of surgical correction of cervical kyphosis on thoraco-lumbo-pelvic sagittal alignment. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2016, 25, 2286–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Wang, J.; Tuchman, A.; Wang, J.; Fu, C.; Hsieh, P.C.; Buser, Z.; Wang, J.C. Influence of T1 Slope on the Cervical Sagittal Balance in Degenerative Cervical Spine: An Analysis Using Kinematic MRI. Spine 2016, 41, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Chang, I.B.; Song, J.H.; Kim, T.H.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, S.W.; Oh, J.K. T1 slope and degenerative cervical spondylolisthesis. Spine 2015, 40, E220–E226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keorochana, G.; Taghavi, C.E.; Lee, K.-B.; Yoo, J.H.; Liao, J.-C.; Fei, Z.; Wang, J.C. Effect of sagittal alignment on kinematic changes and degree of disc degeneration in the lumbar spine: An analysis using positional MRI. Spine 2011, 36, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, M.O.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Alleviation of chronic spine pain and headaches by reducing forward head posture and thoracic hyperkyphosis: A CBP® case report. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.M.; Hegazy, F.A.; Harrison, D.E. Does rehabilitation of cervical lordosis influence sagittal cervical spine flexion extension kinematics in cervical spondylotic radiculopathy subjects? J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2017, 30, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, J.S.; Lipetz, J.S.; Hayes, V.M.; Lonner, B.S. Measurement variability in the assessment of sagittal alignment of the cervical spine: A comparison of the gore and cobb methods. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2004, 17, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bsdc, C.C.; Robinson, D.H. Improvement of Cervical Lordosis and Reduction of Forward Head Posture with Anterior Head Weighting and Proprioceptive Balancing Protocols. J. Vertebral Subluxation Res. Available online: https://vertebralsubluxationresearch.com/2017/09/06/improvement-of-cervical-lordosis-and-reduction-of-forward-head-posture-with-anterior-head-weighting-and-proprioceptive-balancing-protocols/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Morningstar, M. Cervical curve restoration and forward head posture reduction for the treatment of mechanical thoracic pain using the pettibon corrective and rehabilitative procedures. J. Chiropr. Med. 2002, 1, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrantelli, J.R.; Harrison, D.E.; Harrison, D.D.; Stewart, D. Conservative treatment of a patient with previously unresponsive whiplash-associated disorders using clinical biomechanics of posture rehabilitation methods. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2005, 28, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Cailliet, R.; Harrison, D.D.; Janik, T.J.; Holland, B. A new 3-point bending traction method for restoring cervical lordosis and cervical manipulation: A nonrandomized clinical controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.E.; Harrison, D.D.; Betz, J.J.; Janik, T.J.; Holland, B.; Colloca, C.J.; Haas, J.W. Increasing the cervical lordosis with chiropractic biophysics seated combined extension-compression and transverse load cervical traction with cervical manipulation: Nonrandomized clinical control trial. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2003, 26, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.; Taha, S.; Harrison, D.E. Addition of a Sagittal Cervical Posture Corrective Orthotic Device to a Multimodal Rehabilitation Program Improves Short- and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients With Discogenic Cervical Radiculopathy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, M.O.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Non-surgical improvement of cervical lordosis is possible in advanced spinal osteoarthritis: A CBP® case report. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.; Hegazy, F.; Harrison, D.E. Does improvement towards a normal cervical sagittal configuration aid in the management of cervical myofascial pain syndrome: A 1- year randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.; Harrison, D.E. The effect of normalizing the sagittal cervical configuration on dizziness, neck pain, and cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility: A 1-year randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorchuk, C.; Lightstone, D.F.; McCoy, M.; Harrison, D.E. Increased Telomere Length and Improvements in Dysautonomia, Quality of Life, and Neck and Back Pain Following Correction of Sagittal Cervical Alignment Using Chiropractic BioPhysics® Technique: A Case Study. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 2017, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, M.O.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Alleviation of posttraumatic dizziness by restoration of the cervical lordosis: A CBP® case study with a one year follow-up. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wickstrom, B.M.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Non-surgical relief of cervical radiculopathy through reduction of forward head posture and restoration of cervical lordosis: A case report. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1472–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorchuk, C.; Lightstone, D.F.; McRae, C.; Kaczor, D. Correction of Grade 2 Spondylolisthesis Following a Non-Surgical Structural Spinal Rehabilitation Protocol Using Lumbar Traction: A Case Study and Selective Review of Literature. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Cailliet, R.; Harrison, D.D.; Janik, T.J.; Holland, B. Changes in sagittal lumbar configuration with a new method of extension traction: Nonrandomized clinical controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1585–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Diab, A.A.; Moustafa, I.M. Lumbar lordosis rehabilitation for pain and lumbar segmental motion in chronic mechanical low back pain: A randomized trial. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2012, 35, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A. Extension traction treatment for patients with discogenic lumbosacral radiculopathy: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2013, 27, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Oakley, P.A. Non-operative correction of flat back syndrome using lumbar extension traction: A CBP® case series of two. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mendoza-Lattes, S.; Ries, Z.; Gao, Y.; Weinstein, S.L. Natural history of spinopelvic alignment differs from symptomatic deformity of the spine. Spine 2010, 35, E792–E798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhao, W.-K.; Li, M.; Wang, S.-B.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wei, F.; Liu, X.-G.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Z.-J. Analysis of cervical and global spine alignment under Roussouly sagittal classification in Chinese cervical spondylotic patients and asymptomatic subjects. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2015, 24, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Jaeger, J.O.; Brown, J.E.; Polatis, T.A.; Clarke, J.G.; Whittler, C.D.; Harrison, D.E. The CBP® mirror image® approach to reducing thoracic hyperkyphosis: A retrospective case series of 10 patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fortner, M.O.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Treating “slouchy” (hyperkyphosis) posture with chiropractic biophysics®: A case report utilizing a multimodal mirror image® rehabilitation program. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1475–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miller, J.E.; Oakley, P.A.; Levin, S.B.; Harrison, D.E. Reversing thoracic hyperkyphosis: A case report featuring mirror image® thoracic extension rehabilitation. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1264–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Betz, J.W.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Relief of exertional dyspnea and spinal pains by increasing the thoracic kyphosis in straight back syndrome (thoracic hypo-kyphosis) using CBP® methods: A case report with long-term follow-up. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.R.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Nonsurgical correction of straight back syndrome (thoracic hypokyphosis), increased lung capacity and resolution of exertional dyspnea by thoracic hyperkyphosis mirror image® traction: A CBP® case report. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 2058–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Reducing thoracic hyperkyphosis subluxation deformity: A systematic review of Chiropractic Biophysics® methods employed in its structural improvement. J. Contemp. Chiropr. 2018, 1, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ochtman, A.E.A.; Kruyt, M.C.; Jacobs, W.C.H.; Kersten, R.F.M.R.; le Huec, J.C.; Öner, F.C.; van Gaalen, S.M. Surgical Restoration of Sagittal Alignment of the Spine: Correlation with Improved Patient-Reported Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JBJS Rev. 2020, 8, e1900100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.; Visintini, S.; Dunning, C.E.; Oxner, W.M.; Glennie, R.A. Does restoration of focal lumbar lordosis for single level degenerative spondylolisthesis result in better patient-reported clinical outcomes? A systematic literature review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 44, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-W.; Hyun, S.-J.; Kim, K.-J. Surgical Impact on Global Sagittal Alignment and Health-Related Quality of Life Following Cervical Kyphosis Correction Surgery: Systematic Review. Neurospine 2020, 17, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; He, F.; Chen, A.; Yang, H.; Pi, B. Association between sagittal balance and adjacent segment degeneration in anterior cervical surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V.A.; Amin, A.; Omeis, I.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Gottfried, O.N. Implications of spinopelvic alignment for the spine surgeon. Neurosurgery 2015, 76 (Suppl. 1), S42–S56; discussion S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, M.S.; Salotti, J.A.; Little, M.P.; McHugh, K.; Lee, C.; Kim, K.P.; Howe, N.L.; Ronckers, C.M.; Rajaraman, P.; Craft, A.W.; et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2012, 380, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crano, W.D.; Brewer, M.B.; Lac, A. Principles and Methods of Social Research, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-76831-1. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, R.M.; Fowler, J.F., Jr.; Couper, M.P.; Lepkowski, J.M.; Singer, E.; Tourangeau, R. Survey Methodology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-21134-2. [Google Scholar]

| Q2.1: Radiographic procedures in a chiropractic office have value beyond identification of pathology. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q2.2: Radiographs for biomechanical analysis have significant value. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q2.3: I order radiographs only for red flags or pathology. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q2.4: Radiographic procedures are vital to the chiropractic care I provide in my clinic. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q2.5: I utilize radiographic procedures to aid in the measurement of clinical outcomes. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q3: What is your level of agreement/disagreement with the following statement: Based on the educational training and past clinical experiences, the Doctor of Chiropractic should be able to make their own clinical decision regarding the utilization of spinal radiographs on their patients? | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Mostly disagree | 3 = Neutral | 4 = Mostly agree | 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Q4: The foundation of an Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is based on 3 integrated components: (1) Doctor’s Clinical Expertise, (2) Patient Preferences/Values, and (3) Best Research Evidence. When making the clinical decision to obtain spinal radiographs of your patient, should all three EBP components be equally considered? | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Mostly disagree | 3 = Neutral | 4 = Mostly agree | 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Q5: What is your level of agreement/disagreement with the following statement: In my clinical opinion, patient outcomes would benefit from continued research regarding appropriate utilization of spinal radiographs in the practice of chiropractic? | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Mostly disagree | 3 = Neutral | 4 = Mostly agree | 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Q6: What is your level of agreement/disagreement with the following statement: In the absence of published chiropractic research evidence, the doctor’s clinical experience combined with patient preferences are adequate for the appropriate recommendation of spinal radiographs in the practice of chiropractic? | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Mostly disagree | 3 = Neutral | 4 = Mostly agree | 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Q8: What level of risk do you believe is present in your chiropractic practice affecting your patients’ health, as a result of X-ray radiation from your utilization of radiography? | 1 = No risk | 2 = Very low risk | 3 = Low risk | 4 = Moderate Risk | 5 = High risk |

| Q7.1: I do not take radiographs in my clinic. I refer out to another facility. | |||||

| Q9: What is your level of agreement/disagreement with the following statement: In my clinical experience, sharing chiropractic clinical findings from radiographic studies with the patient is beneficial to their clinical outcome? | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Mostly disagree | 3 = Neutral | 4 = Mostly agree | 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Q10.1: To determine adjusting technique or vertebral levels to be adjusted. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q10.2: Mechanical analysis or obtaining measurements of spinal alignment. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q10.3: Future plan modification and considerations. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q10.4: Determine spinal complications such as degenerative changes, anomalies, or defects. | 0 = No | 1 = Yes | |||

| Q10.5: Investigate red flags (fracture, neurologic deficits, suspected pathology). | 0 = No | 1 = Yes |

| Predictor | % |

|---|---|

| Q2: Please select all statements that you agree with regarding spinal radiographs (multiple choices allowed). (n = 4231) | |

| Q2.1: Radiographic procedures in a chiropractic office have value beyond identification of pathology. | 91.9 |

| Q2.2: Radiographs for biomechanical analysis have significant value. | 86.7 |

| Q2.3: I order radiographs only for red flags or pathology. | 16.5 |

| Q2.4: Radiographic procedures are vital to the chiropractic care I provide in my clinic. | 82.9 |

| Q2.5: I utilize radiographic procedures to aid in the measurement of clinical outcomes. | 67.4 |

| Q7: Please select the one answer that best describes your use of general spinal radiography in your practice (This is not regarding advanced imaging such as CT/MRI). (n = 4138) | |

| Q7.1: I do not take radiographs in my clinic. I refer out to another facility. | 24.7 |

| Q7.2: I do have an X-ray machine in clinic, but I still refer patients out to another facility for the majority of my spinal radiographs. | 2.1 |

| Q7.3: I have a plain film X-ray system in my practice and us it for the majority of my radiographs. | 16 |

| Q7.4: I have a DR digital X-ray system in my practice and use it for the majority of my radiographs. | 47.7 |

| Q7.5: I have a CR digital X-ray system in my practice and use it for the majority of my radiographs. (CR digital requires the cassette to be placed into the image processor to process images) | 9.5 |

| Q10: Based on your clinical experience, which reasons are valid to obtain a spinal radiograph in the practice of chiropractic? (choose all that apply): (n = 4106) | |

| Q10.1: To determine adjusting technique or vertebral levels to be adjusted. | 72.1 |

| Q10.2: Mechanical analysis or obtaining measurements of spinal alignment. | 84.5 |

| Q10.3: Future plan modification and considerations. | 81.9 |

| Q10.4: Determine spinal complications such as degenerative changes, anomalies, or defects. | 97.1 |

| Q10.5: Investigate red flags (fracture, neurologic deficits, suspected pathology). | 98.2 |

| Predictor | n | Strongly Agree | Mostly Agree | Neutral | Mostly Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q3 | 4223 | 92.9 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Q4 | 4198 | 43.3 | 34.4 | 9.2 | 7.6 | 4.6 |

| Q5 | 4188 | 60.9 | 21.4 | 11.0 | 4.4 | 2.3 |

| Q6 | 4156 | 56.6 | 27.5 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 3.1 |

| Q8 (No Risk-High Risk) | 4138 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 10.1 | 61.2 | 27.4 |

| Q9 | 4111 | 79.1 | 13.9 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 0.9 |

| No Radiograph | Radiograph | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | % | n | % | n | χ² | |

| Country | 106.34 ** | |||||

| US | 24.4% | 842 | 75.6% | 2603 | ||

| Canada | 30.8% | 137 | 69.2% | 308 | ||

| Outside US and Canada | 58.7% | 105 | 41.3% | 74 | ||

| Q 2.1 | 442.97 ** | |||||

| No | 76.4% | 246 | 23.6% | 76 | ||

| Yes | 22.4% | 838 | 77.6% | 2909 | ||

| Q 2.2 | 450.15 ** | |||||

| No | 64.3% | 343 | 35.4% | 188 | ||

| Yes | 20.9% | 741 | 79.1% | 2797 | ||

| Q 2.3 | 603.52 ** | |||||

| No | 19.1% | 649 | 80.9% | 2751 | ||

| Yes | 65.0% | 435 | 35.0% | 234 | ||

| Q 2.4 | 950.1 ** | |||||

| No | 73.9% | 510 | 26.1% | 180 | ||

| Yes | 17.0% | 574 | 83.0% | 2805 | ||

| Q 2.5 | 564.44 ** | |||||

| No | 50.5% | 663 | 49.5% | 650 | ||

| Yes | 15.3% | 421 | 84.7% | 2335 | ||

| Q 10.1 | 407.49 ** | |||||

| No | 49.1% | 558 | 50.9% | 578 | ||

| Yes | 17.9% | 526 | 82.1% | 2407 | ||

| Q 10.2 | 551.13 ** | |||||

| No | 64.5% | 409 | 35.5% | 225 | ||

| Yes | 19.7% | 657 | 80.3% | 2760 | ||

| Q 10.3 | 174.09 ** | |||||

| No | 46.0% | 341 | 54.0% | 400 | ||

| Yes | 22.3% | 743 | 77.7% | 2585 | ||

| Q 10.4 | 153.05 ** | |||||

| No | 75.0% | 93 | 25.0% | 31 | ||

| Yes | 25.1% | 991 | 74.9% | 2954 | ||

| Q 10.5 | 0.95 | |||||

| No | 31.3% | 26 | 68.7% | 57 | ||

| Yes | 26.5% | 1058 | 73.5% | 2928 | ||

| Predictor | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q3 | 4069 | 4.9 | 0.44 |

| Q4 | 4069 | 4.07 | 1.12 |

| Q5 | 4069 | 4.35 | 0.98 |

| Q6 | 4069 | 4.3 | 1.02 |

| Q8 | 4069 | 1.85 | 0.65 |

| Q9 | 4069 | 4.68 | 0.73 |

| Predictor | B | SE | Wald | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||

| US | 1.99 | 0.17 | 130.88 | 7.36 ** |

| Canada | 1.16 | 0.2 | 33.18 | 3.17 ** |

| Q 2.1 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 3.96 | 1.54 * |

| Q 2.2 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 9.15 | 1.72 ** |

| Q 2.3 | −0.98 | 0.13 | 58.52 | 0.38 ** |

| Q 2.4 | 1.78 | 0.13 | 178.23 | 5.93 ** |

| Q 2.5 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 57.18 | 2.23 ** |

| Q 3 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| Q 4 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 1.01 |

| Q 5 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.97 |

| Q 6 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.82 | 1.06 |

| Q 8 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.02 |

| Q 9 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 5.27 | 1.18 * |

| Q 10.1 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 9.52 | 1.42 ** |

| Q 10.2 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 4.48 | 1.4 * |

| Q 10.3 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 11.45 | 1.57 ** |

| Q 10.4 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 1.74 | 1.51 |

| Q 10.5 | −0.32 | 0.31 | 1.04 | 0.73 |

| Item | Loadings | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Q 2.1 | 0.95 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 2.2 | 0.95 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 2.3 | 0.71 ** | 0.02 |

| Q 2.4 | 0.87 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 2.5 | 0.82 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 10.1 | 0.88 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 10.2 | 0.95 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 10.3 | 0.84 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 10.4 | 0.97 ** | 0.01 |

| Q 10.5 | 0.87 ** | 0.01 |

| Item | χ² | df | Difficulty | Outfit MSQ | Infit MSQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q 2.1 | 1111.56 | 4110 | −1.92 | 0.27 | 0.69 |

| Q 2.2 | 1409.32 | 4110 | −1.51 | 0.34 | 0.69 |

| Q 2.3 | 51,793.5 | 4110 | 1.39 | 12.60 | 1.32 |

| Q 2.4 | 2074.18 | 4110 | −1.27 | 0.51 | 0.82 |

| Q 2.5 | 2657.84 | 4110 | −0.55 | 0.65 | 0.76 |

| Q 10.1 | 2027.26 | 4110 | −0.66 | 0.49 | 0.66 |

| Q 10.2 | 1210.89 | 4110 | −1.22 | 0.30 | 0.52 |

| Q 10.3 | 1983.27 | 4110 | −1.09 | 0.48 | 0.75 |

| Q 10.4 | 773.515 | 4110 | −2.15 | 0.19 | 0.65 |

| Q 10.5 | 1707.58 | 4110 | −2.28 | 0.42 | 0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnone, P.A.; Kraus, S.J.; Farmen, D.; Lightstone, D.F.; Jaeger, J.; Theodossis, C. Examining Clinical Opinion and Experience Regarding Utilization of Plain Radiography of the Spine: Evidence from Surveying the Chiropractic Profession. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062169

Arnone PA, Kraus SJ, Farmen D, Lightstone DF, Jaeger J, Theodossis C. Examining Clinical Opinion and Experience Regarding Utilization of Plain Radiography of the Spine: Evidence from Surveying the Chiropractic Profession. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(6):2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062169

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnone, Philip A., Steven J. Kraus, Derek Farmen, Douglas F. Lightstone, Jason Jaeger, and Christine Theodossis. 2023. "Examining Clinical Opinion and Experience Regarding Utilization of Plain Radiography of the Spine: Evidence from Surveying the Chiropractic Profession" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 6: 2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062169

APA StyleArnone, P. A., Kraus, S. J., Farmen, D., Lightstone, D. F., Jaeger, J., & Theodossis, C. (2023). Examining Clinical Opinion and Experience Regarding Utilization of Plain Radiography of the Spine: Evidence from Surveying the Chiropractic Profession. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(6), 2169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062169