Gender-Related Outcomes after Surgical Resection and Level of Satisfaction in Patients with Left Atrial Tumors

Abstract

1. Introduction

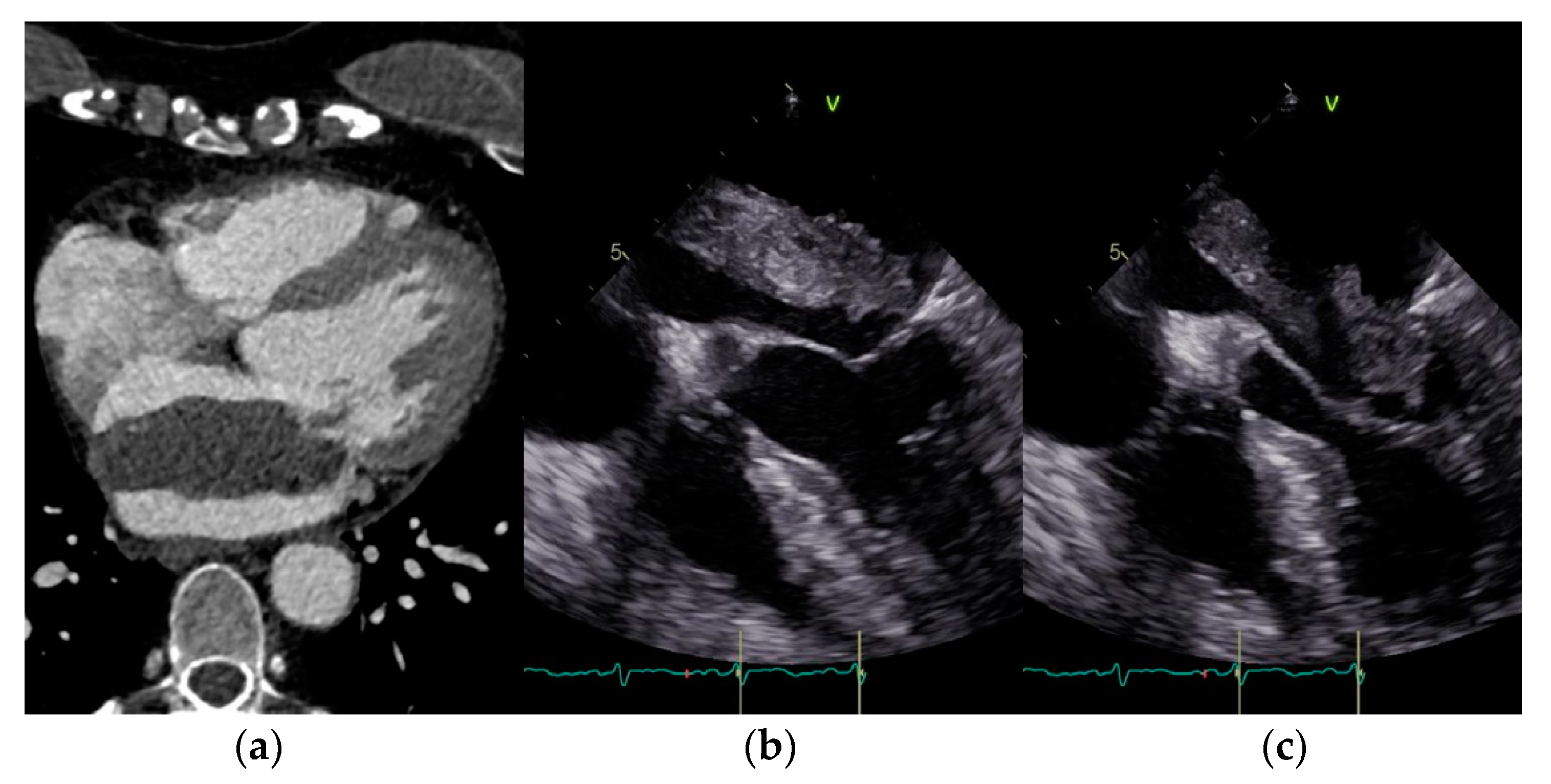

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

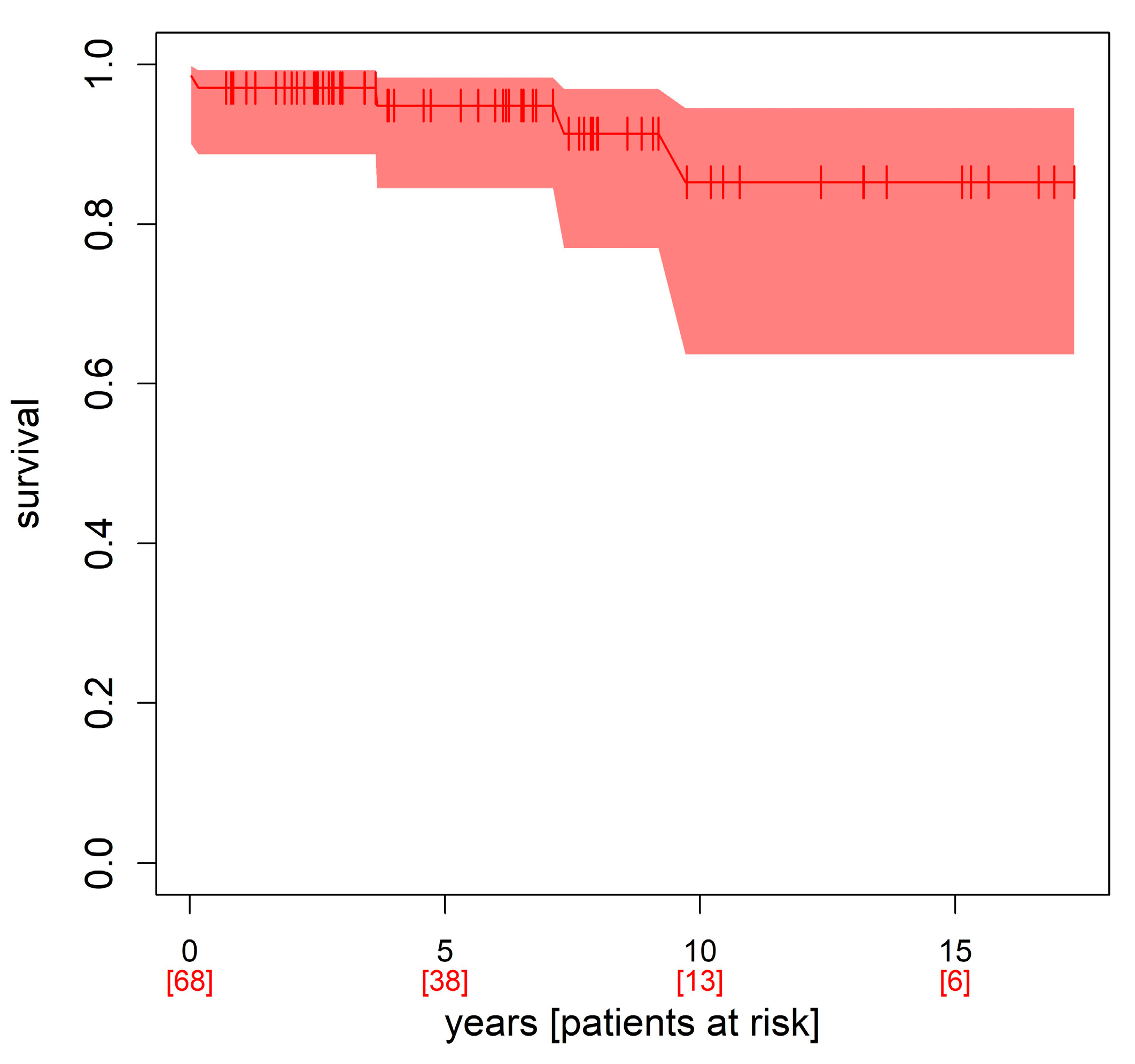

Follow-Up Data and Level of Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reynen, K. Cardiac myxomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grebenc, M.L.; Rosado de Christenson, M.L.; Burke, A.P.; Green, C.E.; Galvin, J.R. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2000, 20, 1073–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjessmo, S.; Ivert, T. Cardiac myxoma: 40 years’ experience in 63 patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997, 63, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasoglu, I.; Tutun, U.; Lafci, G.; Hijaazi, A.; Yener, U.; Yalcinkaya, A.; Ulus, T.; Aksoyek, A.; Saritas, A.; Birincioglu, L.; et al. Primary cardiac myxomas: Clinical experience and surgical results in 67 patients. J. Card. Surg. 2009, 24, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Vito, A.; Mignogna, C.; Donato, G. The Mysterious Pathways of Cardiac Myxomas: A Review of Histogenesis, Pathogenesis and Pathology. Histopathology 2015, 66, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdil, N.; Ates, S.; Cetin, L.; Demirkilic, U.; Sener, E.; Tatar, H. Frequency of Left Atrial Myxoma with Concomitant Coronary Artery Disease. Surg. Today 2003, 33, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, F.H.; Hale, D.; Cohen, A.; Thompson, L.; Pezzella, A.T.; Virmani, R. Primary cardiac valve tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1991, 52, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudzik, B.; Miszalski-Jamka, K.; Glowacki, J.; Lekston, A.; Gierlotka, M.; Zembala, M.; Polonski, L.; Gasior, M. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A.; Virmani, R. Tumors of the Heart and Great Vessels (Atlas of Tumor Pathology 3rd Series), 1st ed.; Amer Registry of Pathology: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1996; pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, P.; Aung, M.M.; Awan, M.U.; Kososky, C.; Barn, K. A Case of Large Atrial Myxoma Presenting as an Acute Stroke. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2016, 6, 29604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Terry, T.M.; Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-387-98784-3. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, V.D.; de Campos, F.P. Cardiac Myxoma. Autops. Case Rep. 2016, 6, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabe, E.D.; Rodríguez Correa, C.; Vigliano, C.; San Martino, J.; Wisner, J.N.; González, P.; Boughen, R.P.; Torino, A.; Suárez, L.D. Cardiac myxoma. Clinical-pathological cor-relation. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2002, 55, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gismondi, R.A.; Kaufman, R.; Correa, G.A.; Nascimento, C.; Weitzel, L.H.; Reis, J.O.B.; Rocha, A.S.C.D.; Cunha, A.B.D. Left atrial myxoma associated with obstructive coronary artery disease. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2007, 88, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kannel, W.B.; Hjortland, M.C.; McNamara, P.M.; Gordon, T. Menopause and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Framingham study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1976, 85, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, L.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Wenger, N.K. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: What a difference a decade makes. Circulation 2011, 124, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaideeswar, P.; Butany, J.W. Benign cardiac tumors of the pluripotent mesenchyme. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2008, 25, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garatti, A.; Nano, G.; Canziani, A.; Gagliardotto, P.; Mossuto, E.; Frigiola, A.; Menicanti, L. Surgical excision of cardiac myxomas: Twenty years experience at a single institution. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 93, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Xiao, J.; Chen, J.; Hong, J.; Peng, H.; Kang, B.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z. Treating cardiac myxomas: A 16-year Chinese singlecenter study. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 17, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, R.P.; Ramírez, M.A.; Zalaquett, S.R.; Moran, V.S.; Irarrázaval, L.I.M.J.; Arretz, V.C.; Córdova, A.S.; Arnaiz, G.P. Cardiac myxoma: Clinical characterization. diagnostic methods and late surgical results. Rev. Med. Chile 2008, 136, 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kalavrouziotis, D.; Li, D.; Buth, K.J.; Légaré, J.F. The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) is not appropriate for withholding surgery in high-risk patients with aortic stenosis: A retrospective cohort study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2009, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (Patients) n = 80 | Female Patients | Male Patients | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 62.76 ± 13.42 | 59.65 ± 15.84 | 0.438 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 27.36 ± 6.16 | 27.09 ± 5.75 | 0.945 |

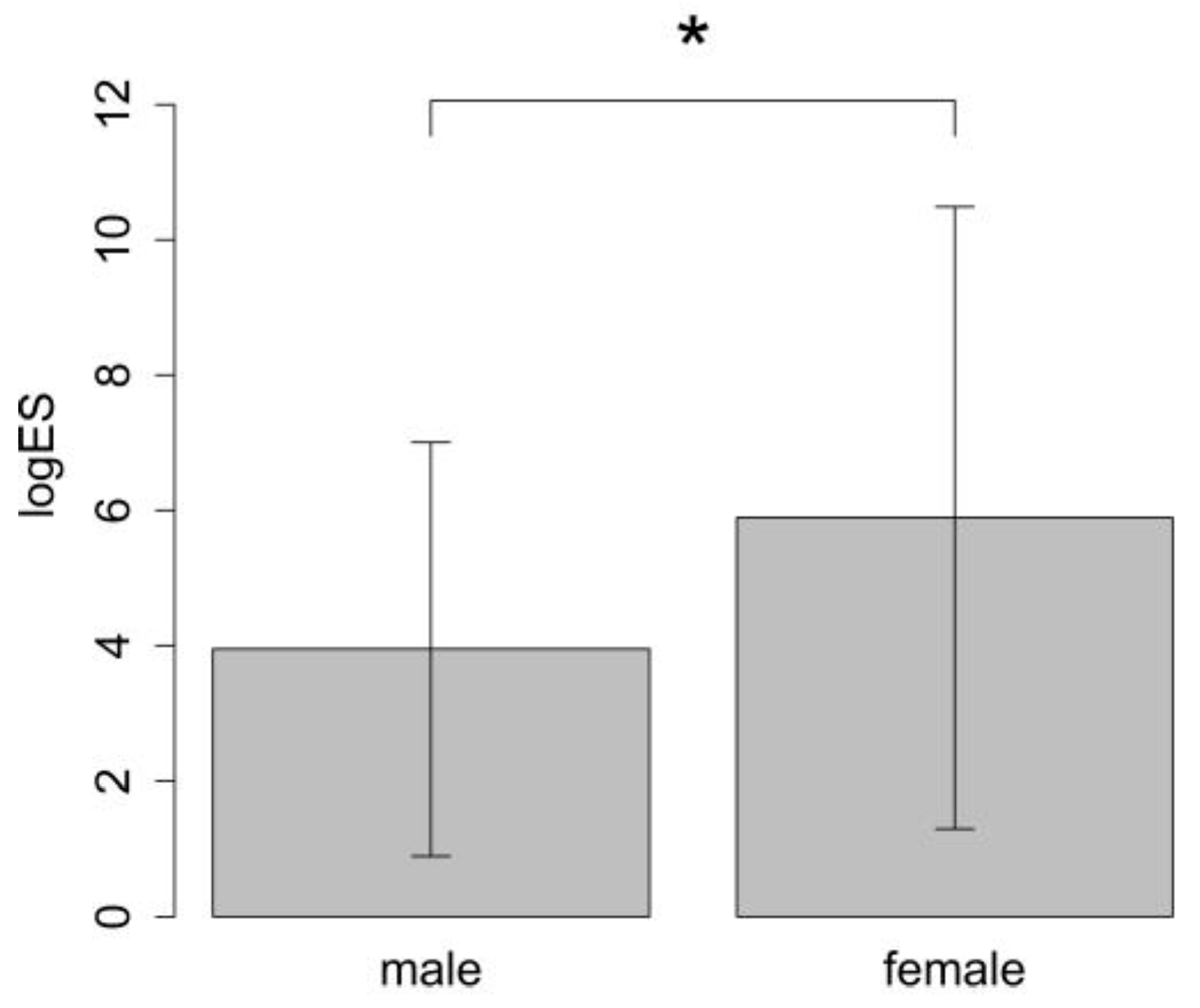

| Euroscore | 5.42 ± 2.41 | 4.04 ± 2.14 | 0.013 |

| Logistic ES | 5.89 ± 4.6 | 3.95 ± 3.06 | 0.017 |

| ES II | 2.07 ± 2.1 | 0.94 ± 0.45 | 0.043 |

| X-clamp time [min] | 41.62 ± 29.61 | 41.8 ± 37.8 | 0.6 |

| Bypass time [min] | 77.45 ± 40.86 | 71.73 ± 45.28 | 0.24 |

| In hospital stay [d] | 17.25 ± 23.52 | 16.92 ± 10.46 | 0.399 |

| LV-EF preoperative | 59.21 ± 5.1 | 57.67 ± 10.19 | 0.247 |

| LV-EF postoperative | 58.07 ± 5.99 | 57.5 ± 7.98 | 0.847 |

| Postoperative wound-healing problems | 3.85% [2] | 7.69% [2] | 0.597 |

| Symptoms | Female Patients | Male Patients | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea | 25.49% [13] | 16% [4] | 0.398 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27.45% [14] | 19.23% [5] | 0.609 |

| TIA | 11.76% [6] | 0% [0] | 0.169 |

| Stroke | 19.61% [10] | 12% [3] | 0.526 |

| Pulmonary diseases | 15.69% [8] | 24% [6] | 0.573 |

| Angina pectoris | 11.76% [6] | 8% [2] | 1 |

| Fever | 0% [0] | 8% [2] | 0.105 |

| Arterial hypertension | 70.59% [36] | 61.54% [16] | 0.586 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19.61% [10] | 16% [4] | 1 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 39.22% [20] | 40% [10] | 1 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Female | Male | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 78.43% [40] | 68% [17] | 0.481 |

| 1 | 7.84% [4] | 4% [1] | 1 |

| 2 | 11.76% [6] | 12% [3] | 1 |

| 3 | 1.96% [1] | 16% [4] | 0.038 |

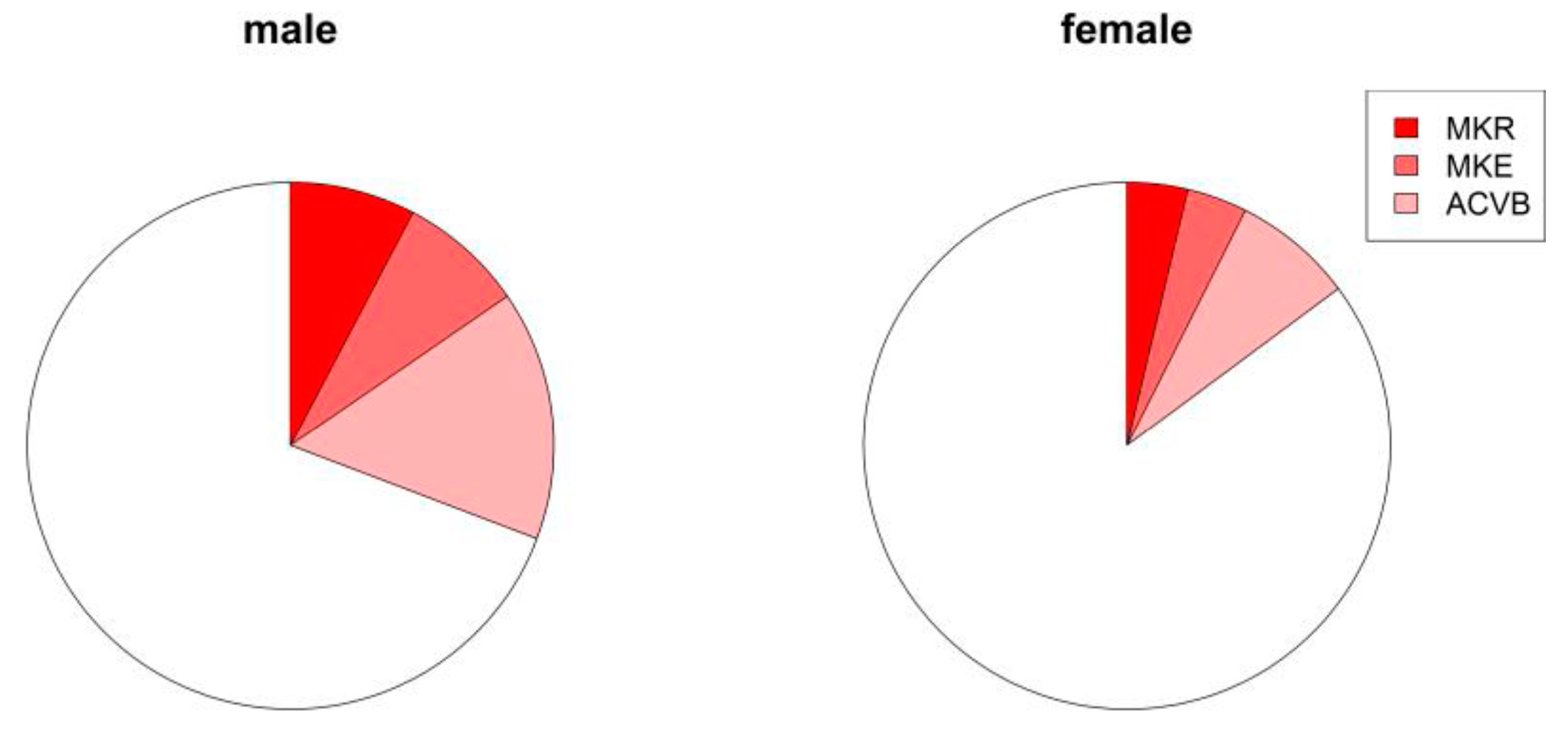

| Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting | Female | Male | p |

| 0 | 92.59% [50] | 84.62% [22] | 0.427 |

| 1 | 3.7% [2] | 0% [0] | 1 |

| 2 | 3.7% [2] | 3.85% [1] | 1 |

| 3 | 0% [0] | 11.54% [3] | 0.032 |

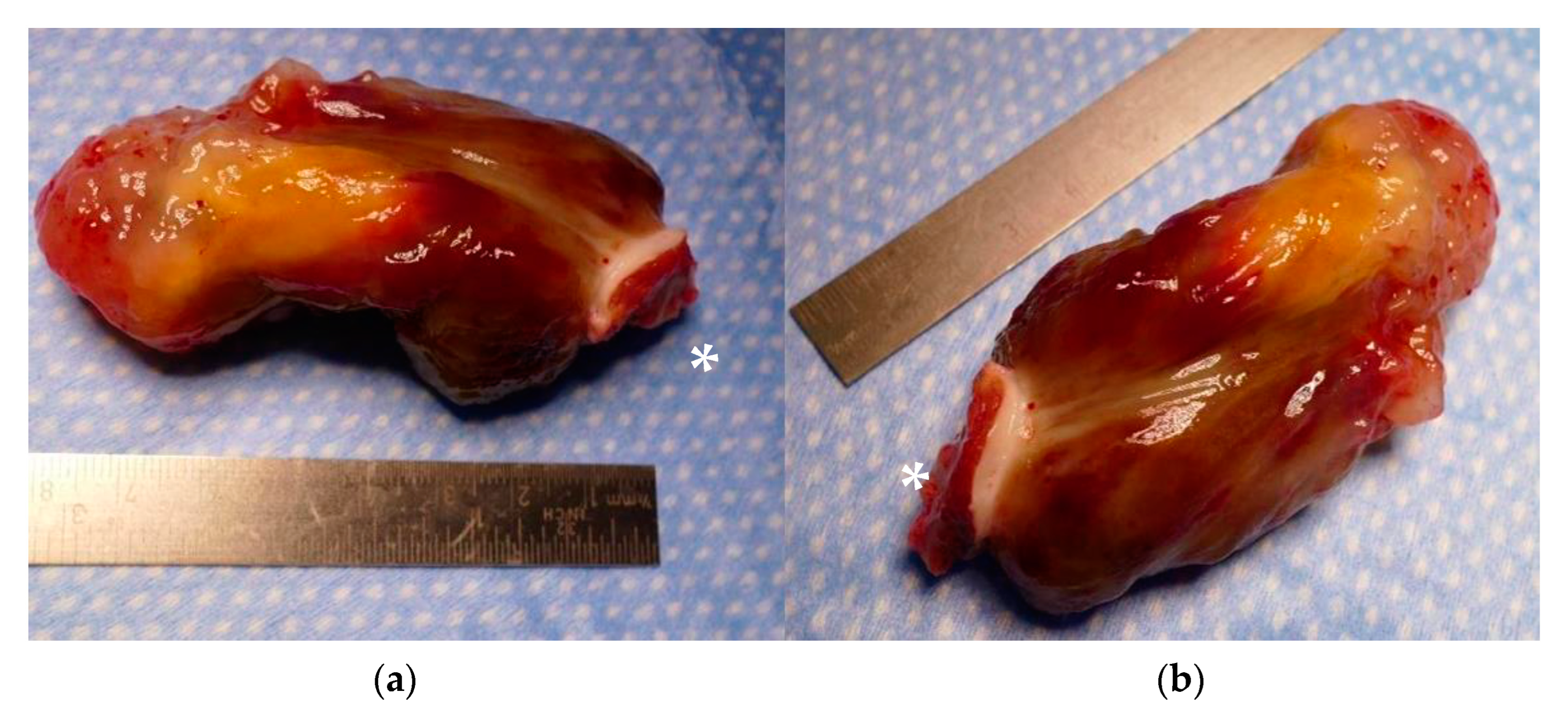

| Histopathology | n | % | Male. n | Male. % | Female. n | Female. % | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myxoma | 55 | 68.75 | 18 | 72 | 37 | 67.27 | 1 |

| Thrombus | 11 | 13.75 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 16.36 | 0.496 |

| Fibroelastoma | 8 | 10.00 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 10.91 | 1 |

| Hamartoma | 1 | 1.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.321 |

| Thyroid gland | 1 | 1.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.82 | 1 |

| Thymus | 1 | 1.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.82 | 1 |

| Metastasis | 1 | 1.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.321 |

| Sarcoma | 1 | 1.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.82 | 1 |

| Carcinoid | 1 | 1.25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.321 |

| Total Number of Patients | 80 (100%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients who have died | 11 (13.75%) |

| Number of patients who were alive in 2023 | 69 (86.25%) |

| Heart disease as cause of death | 3 |

| Cancer as cause of death | 1 |

| COVID-19 as cause of death | 2 |

| Unclear cause of death | 5 |

| Could not be reached by phones | 3 |

| Follow-up patients | 66 (82.5%) |

| n = 66 | Very Satisfied | Satisfied | Neutral | Unsatisfied | Very Unsatisfied | Patient Reached by Phone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Satisfaction with perioperative treatment | 57 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | n = 66 |

| Male | 15 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Female | 42 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| n = 66 | Very Satisfied | Satisfied | Neutral | Unsatisfied | Very Unsatisfied | Patient Reached by Phone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 14 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | n = 66 |

| Female | 39 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Male Mean | Male Median | Female Mean | Female Median | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with perioperative treatment | 1.2 ± 0.41 | 1 | 1.15 ± 0.47 | 1 | 0.38 |

| Satisfaction today | 1.3 ± 0.57 | 1 | 1.22 ± 0.51 | 1 | 0.499 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sido, V.; Volkwein, A.; Hartrumpf, M.; Braun, C.; Kühnel, R.-U.; Ostovar, R.; Schröter, F.; Chopsonidou, S.; Albes, J.M. Gender-Related Outcomes after Surgical Resection and Level of Satisfaction in Patients with Left Atrial Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12052075

Sido V, Volkwein A, Hartrumpf M, Braun C, Kühnel R-U, Ostovar R, Schröter F, Chopsonidou S, Albes JM. Gender-Related Outcomes after Surgical Resection and Level of Satisfaction in Patients with Left Atrial Tumors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(5):2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12052075

Chicago/Turabian StyleSido, Viyan, Annika Volkwein, Martin Hartrumpf, Christian Braun, Ralf-Uwe Kühnel, Roya Ostovar, Filip Schröter, Sofia Chopsonidou, and Johannes Maximilian Albes. 2023. "Gender-Related Outcomes after Surgical Resection and Level of Satisfaction in Patients with Left Atrial Tumors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 5: 2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12052075

APA StyleSido, V., Volkwein, A., Hartrumpf, M., Braun, C., Kühnel, R.-U., Ostovar, R., Schröter, F., Chopsonidou, S., & Albes, J. M. (2023). Gender-Related Outcomes after Surgical Resection and Level of Satisfaction in Patients with Left Atrial Tumors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(5), 2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12052075