Abstract

Gingivitis and periodontitis are chronic inflammatory diseases that affect the supporting tissues of the teeth. Although induced by the presence of bacterial biofilms, other factor, such as tobacco smoking, drugs, and various systemic diseases, are known to influence their pathogenesis. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases correspond to inflammatory diseases that have pathogenic mechanisms in common, with the involvement of pro-inflammatory mediators. A bidirectional relationship between type 2 diabetes and periodontitis has been documented in several studies. Significantly less studies have focused on the association between periodontal disease and type 1 diabetes. The aim of the study is to analyze the association between periodontal status and type 1 diabetes mellitus. The “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines” was used and registered at PROSPERO. The search strategy included electronic databases from 2012 to 2021 and was performed by two independent reviewers. According to our results, we found one article about the risk of periodontal diseases in type 1 diabetes mellitus subjects; four about glycemic control; two about oral hygiene; and eight about pro-inflammatory cytokines. Most of the studies confirm the association between type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. The prevalence and severity of PD was higher in DM1 patients when compared to healthy subjects.

1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1), also known as insulin-dependent diabetes or juvenile diabetes, has an idiopathic or autoimmune cause in which there is a destruction of the pancreatic β-cells [1,2,3,4]. It can be diagnosed at any age, but this type of diabetes often manifests itself in children, adolescents, and young adults [4]. According to the American Diabetes Association, type 1 diabetes represents about 5–10% of patients with diabetes [5,6].

Several clinical studies suggest that diabetes mellitus is a risk factor in the prevalence, progression, and severity of periodontal disease (PD). According to some authors, periodontal disease is considered the sixth most common complication of diabetes [6,7,8,9].

PD is a chronic inflammatory disease that causes the destruction of the tissues that support the tooth. This inflammatory process is caused by the presence of Gram-negative bacteria, which accumulate along the tooth margin, promoting a chronic and progressive local inflammatory response [5,10,11,12,13,14]. Gingivitis and periodontitis are the two forms of periodontal disease. Gingivitis is a superficial inflammation of the periodontium in which there is no attachment loss. When left untreated, it can reach the deep periodontium, evolving to periodontitis, which is an irreversible inflammation of the periodontium with tissue destruction and bone resorption [12,15]. The consequent loss of support structure can lead to loss of tooth parts and systemic inflammation [11,16].

Diabetes mellitus and PD correspond to inflammatory diseases that have pathogenic mechanisms in common, with the involvement of pro-inflammatory mediators [17]. According to some studies, the presence of elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators in the gingival tissues of diabetic patients, such as IL1-β (interleukin 1 beta), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), IL-6 (interleukin 6), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), prostaglandins (PGs), nuclear factor-kappa B receptor activator ligand/osteoprotegerin relationship (RANK-L/OPG), and oxidative stress, plays an important role in the initiation and progression of periodontal disease [7,8,9,17,18].

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is associated with elevated levels of systemic markers of inflammation. The elevated inflammatory state in diabetes contributes to both microvascular and macrovascular complications, and hyperglycemia can result in the activation of pathways that enhance inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis [19].

The level of glycemic control is of key importance in determining increased risk of periodontal disease. The glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test is also widely used for the detection and control of diabetes mellitus. This test determines the amount of glucose that is irreversibly bound to the hemoglobin molecule of red blood cells and which will remain bound throughout its lifetime, around 30 to 90 days. The normal value for hemoglobin HbA1c is less than 6.5%; the higher the glucose level, the higher the percentage of glycated hemoglobin [19,20].

Although there are already plenty of studies on PD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), studies on the relationship of PD and DM1 remain scarce. The main objective of this systematic review is to analyze the association between periodontal status and type 1 diabetes mellitus and evaluate the effects of glycemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus subjects with periodontal disease.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted from June 2022 to September 2022, according to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines” (PRISMA) [21] using the databases MEDLINE via PubMed and Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Scopus (from January of 2012 to November of 2022). The search was also conducted using the following journals: Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Journal of Periodontology, and Periodontology 2000 via Wiley Online Library (2012 to present). The research strategy used was: (type 1 diabetes mellitus [MeshTerms]) and (periodontal disease [MeshTerms]); (type 1 diabetes mellitus [MeshTerms]) and (periodontitis [MeshTerms]); (type 1 diabetes mellitus [MeshTerms]) and (chronic periodontitis [MeshTerms]); (gingivitis [MeshTerms]) and (type 1 diabetes mellitus [MeshTerms]).

Records were screened by the title, abstract, and full text by two independent investigators. Studies included in this review matched all the predefined criteria according to PICOS (“Population”, “Intervention”, “Comparison”, “Outcomes”, and “Study design”). A detailed search flowchart is presented in the Results section.

The study protocol for this systematic review was registered on the International Prospective of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), under number CRD42022385448.

The eligibility criteria were organized, using the PICO method, as follows:

- − P (population): Type 1 Diabetic patients;

- − I (intervention/exposure): Periodontal disease;

- − C (comparison): Patients without periodontal disease;

- − O (outcome): to analyze the association between type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease.

The inclusion criteria corresponding to the PICO’s questions were articles in English, Portuguese, or Spanish, articles related to DM1, and cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, cohort studies, and randomized controlled clinical studies. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were articles without an abstract available, literature reviews and meta-analyses, expert opinions, letters to editor, conference abstracts, animal studies, and studies investigating DM2 exclusively. We also excluded inflammatory diseases, chronic liver disease, or articles related to any treatment that may modify study parameters such as antibiotics, immunosuppressants, or antiepileptic drugs.

2.1. Extraction of Sample Data

The data were collected by drawing up a results table, and the information was collected taking into consideration the study design and aim, the eligibility criteria, the study population (with sample size and age group or average age), the duration in months or years of the study as well as the follow-up period, and the outcome measures and results.

2.2. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

To assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct, or analysis, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance 2017 for each type of study (cross-sectional, case-control, cohort studies, or randomized controlled trials) [22]. For each type of study, a different questionnaire was conducted using the answers Yes (Y), No (n), Unclear (UN), Not/Applicable (NA). Two independent examiners (R.C./M.R.) were used to demonstrate intra- and inter-examiner reliability.

3. Results

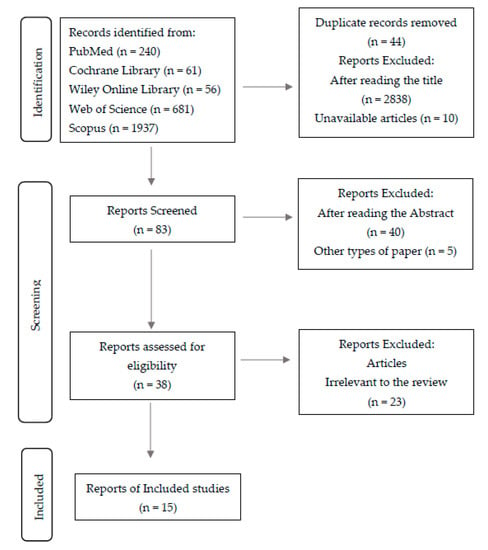

In total, 2975 studies were initially identified, and after removing duplicates and excluding articles by title and abstract, we investigated in a full-text analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Finally, 15 cohort studies were included in our meta-analysis; the characteristics of all included studies are presented in the Table 5.

Figure 1 shows the detailed selection strategy of the articles.

3.1. Characterization of the Sample for the Quality of the Study

Quality assessments are shown in Table 1 for cross-sectional studies, Table 2 for case-control Studies, Table 3 for randomized controlled trials, and Table 4 for cohort studies.

The degree of quality of the studies on the relational index used and the number of positive responses to the questions are mostly high, including nine articles [7,11,20,23,24,25,26,27,28], although we can also find five studies with moderate evidence [3,9,18,29,30] and one of low quality [8].

Table 1.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies.

Table 1.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies.

| Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies. | 1. Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | 2. Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | 3. Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 4. Were Objective, Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | 5. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 6. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 7. Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 8. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonoglou et al. [18], 2013 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | UN | Y | Y |

| Dakovic et al. [9], 2013 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | UN | Y | Y |

| Poplawska-Kita et al. [7], 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UN | Y | Y |

| Jindal et al. [29], 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | UN | Y | Y |

| Lappin et al. [23], 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ismail et al. [24], 2017 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Roy et al. [25], 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UN |

| Dicembrini et al. [11], 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jensen et al. [26], 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UN | Y | Y |

Table 2.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Control Studies.

Table 2.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Control Studies.

| Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Control Studies. | 1. Were the Groups Comparable other than the Presence of Disease in Cases or the Absence of Disease in Controls? | 2. Were Cases and Controls Matched Appropriately? | 3. Were the Same Criteria Used for Identification of Cases and Controls? | 4. Was Exposure Measured in a Standard, Valid, and Reliable Way? | 5. Was Exposure Measured in the Same Way for Cases and Controls? | 6. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 7. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 8. Were Outcomes Assessed in a Standard, Valid, and Reliable Way for Cases and Controls? | 9. Was the Exposure Period of Interest Long Enough to be Meaningful? | 10. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zizzi et al. [27], 2013 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Linhartova et al. [28], 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Keles et al. [30], 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UN | UN | Y | Y | Y |

| Sereti et al. [3], 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UN | UN | Y | Y | Y |

Table 3.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials.

Table 3.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials.

| Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials. | 1. Was True Randomization Used for Assignment of Participants to Treatment Groups? | 2. Was Allocation to Treatment Groups Concealed? | 3. Were Treatment Groups Similar at the Baseline? | 4. Were Participants Blind to Treatment Assignment? | 5. Were Those Delivering Treatment Blind to Treatment Assignment? | 6. Were Outcomes Assessors Blind to Treatment Assignment? | 7. Were Treatment Groups Treated Identically Other than the Intervention of Interest? | 8. Was Follow up Complete and If Not, Were Differences between Groups in Terms of Their Follow up Adequately Described and Analyzed? | 9. Were Participants Analyzed in the Groups to Which They Were Randomized? | 10. Were Outcomes Measured in the Same Way for Treatment Groups? | 11. Were Outcomes Measured in a Reliable Way? | 12. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | 13. Was the Trial Design Appropriate, and any Deviations from the Standard RCT Design (Individual Randomization, Parallel Groups) Accounted for in the Conduct and Analysis of the Trial? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajita et al. [8], 2013 | N | Y | NA | N | NA | N | NA | N | N | NA | N | NA | NA |

Table 4.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies.

Table 4.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies.

| Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies. | 1. Were the Two Groups Similar and Recruited from the Same Population? | 2. Were the Exposures Measured Similarly to Assign People to both Exposed and Unexposed Groups? | 3. Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 4. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 5. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 6. Were the Groups/Participants Free of the Outcome at the Start of the Study (or at the Moment of Exposure)? | 7. Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 8. Was the Follow up Time Reported and Sufficient to Be Long Enough for Outcomes to Occur? | 9. Was Follow up Complete, and If Not, Were the Reasons to Loss to Follow up Described and Explored? | 10. Were Strategies to Address Incomplete Follow up Utilized? | 11. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun et al. [20], 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y |

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

From each eligible study included in the present systematic review, we collected data about general characteristics, such as study design and aim, inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the study population (with sample size and age group or average age), the duration in months or years of the study, as well as the follow-up period and the outcome measures and results (Table 5).

Table 5.

The main characteristics of the included studies.

According to our results, we found one article about the risk of periodontal diseases in type 1 diabetes mellitus subjects; four about glycemic control; two about oral hygiene; and eight about pro-inflammatory cytokines.

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review is to analyze the association between type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease.

There is emerging evidence of a two-way relationship between diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases, with diabetes increasing the risk of periodontitis and periodontal inflammation negatively affecting glycemic control [1,6,7].

According to our results, there seems to be an association between PD and DM1, and the prevalence and severity of PD was higher in DM1 patients when compared to healthy controls [7,8,11,20]. Sun et al. [20] confirmed that DM1 patients exhibited an increased risk of PD (aHR = 1.45; p < 0.001) when compared to non-diabetic patients. In addition, the hazard of developing PD was markedly increased in DM1 patients with increased annual emergency room visits and hospitalizations for their diabetes (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 13.0 and 13.2, respectively, p < 0.001). Concerning the two specific types of PD, DM1 patients had a 1.47-fold higher risk to develop gingivitis (95% CI = 1.36–1.59) and 1.66-fold higher risk to develop periodontitis (95% CI = 1.41–1.96), when compared to non-DM1 subjects. People aged 20–40 had a lower incidence of gingivitis and a higher incidence of periodontitis than those aged <20 in both case and control groups [20].

4.1. Glycemic Control

The evidence suggests that the level of glycemic control is of key importance in determining increased risk of periodontal disease [7,19,31]. For this reason, periodontal literature used categorical values for Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c) as seen in the new consensus report of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions for the staging and grading of periodontitis [32]. From our results, four articles were found that support this theory [7,8,26,29]. The goal of research led by Dicembrini et al. [11] was to investigate the prevalence of PD in DM1 patients and its association with glycemic control and glucose variability. A significant correlation was found between mean Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL) and Glucose Coefficient Variation (CV) (r = 0.31, p = 0.002), but not with Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c) (r = 0.038 p = 0.673). Furthermore, mean Periodontal Probing Depths (PPD) were associated with CV but not with HbA1c (r = 0.27 and 0.044; p = 0.007 and 0.619, respectively). A positive correlation between the CV and DM1 was seen after adjusting for the main confounders.

In another study, conducted by Jensen et al. [26], the worsening of glycemic control was associated with increased severity of early markers of periodontal disease in children and adolescents with DM1. The HbA1c was positively correlated with plaque index (PI) (Rho = 0.34; p = 0.002), gingival index (GI) (Rho = 0.30; p = 0.009), bleeding on probing (BOP) (Rho = 0.44; p = 0.0001), and periodontal probing depths (PPD) > 3 mm (Rho = 0.21; p = 0.06).

Furthermore, Jindal et al. [29] investigated the relationship between the severity of PD and glycemic control in DM1 patients in a hospital-based study, and the DM1 patients with poor metabolic control (PMC) exhibited increased inflammation (p < 0.005), more dental plaque, and clinical attachment loss when compared to those with fair and good glycemic control (GMC).

The study of Ajita et al. [8] showed that the bleeding index was significantly higher in DM1 patients, suggesting greater susceptibility for PD. When comparing the poor metabolic control patients with ones with good metabolic control, significant differences were recorded in PPD (p < 0.001), Bleeding Index (BI) (p < 0.001), and Clinical attachment Loss (CAL) (p = 0.001). CAL, BI, and PPD were greater in DM1 patients than in non-DM1 patients (4.337 ± 0.648 vs. 2.300 ± 0.557, respectively, p = 0.001; 2.708 ± 0.390 vs. 1.760 ± 0.434 respectively, p < 0.001; and 6.337 ± 0.650 vs. 5.181 ± 0.705, respectively, p < 0.001). The results showed a correlation between the bleeding index and disease severity in patients diagnosed with diabetes in a short period of time (4–7 years) (1.760 ± 0.434). On the other hand, longer durations of DM1 were associated with greater CAL.

Another study by Poplawska-Kita et al. [7] studied the role of hyperglycemia in the development of periodontal disease. According to their study, periodontitis was found in 57.9% of DM1 patients, including 59.5% of these with poor metabolic control, which highlights the relationship between glycemic control and the increased risk of periodontal disease in DM1 subjects.

4.2. Advanced Glycated-End Products

The presence of chronic hyperglycemia is related to the increased production of Advanced Glycated-End products (AGEs). AGEs are implicated in suppressed collagen production by gingival and periodontal ligament fibroblasts [3,27]. In addition, the binding of AGEs to a receptor increases the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF)-α, and interleukin-6 (IL-6), involved in periodontal destruction [19,33].

The study of Zizzi et al. [27] attempted to evaluate the expression of AGEs in Diabetes-Mellitus-associated periodontitis. According to their findings, AGE-positive cells were not found either in fibroblasts or in gingival inflammatory cell infiltrates in subjects of the control group and in the group of systematically healthy individuals affected by chronic periodontitis. On the other hand, in the group of subjects with DM1 affected by chronic periodontitis, there was found a positive correlation between the duration of DM and the percentage of AGE-positive cells in epithelium (r: 0.610; p: 0.012), vessels (0.635; p: 0.008), and fibroblasts (r = 0.589; p: 0.016). A positive association was found between gingival expression of AGEs and the duration of DM1.

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory process caused by Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria that are present in bacterial plaque along the tooth margin, causing a chronic and progressive response. For this reason, the presence of inadequate oral hygiene might contribute to the development of periodontal inflammation and further tissue destruction [34]. According to our research, there are two studies that support that evidence [24,25]. The study of Ismail et al. [24] showed that children with DM1 exhibited significantly greater plaque deposits (p = 0.01), a higher mean plaque index (p < 0.01), and a greater percentage of sites with bleeding on probing (p > 0.05) when compared to non-diabetics. Furthermore, the study by Sereti et al. [3] showed that the mean of GI, BOP, and the number of sites with PI and GI score > 1 was markedly higher in the DM1 group as compared to the controls. Moreover, the results by Roy et al. [25] showed that the mean presence of plaque, GI, and BOP and the mean sites with GI score ≥ 1 were appreciably higher in the DM1 group than in the control group, which suggests that these subjects will be more susceptible to developing periodontitis in the future. However, concerning the diagnosis of periodontal disease, no significant differences were observed. Gingivitis was present in 68% of the diabetics and 60% of nondiabetic subjects. Concerning the presence of periodontitis, fourteen patients of the control group had a diagnosis of periodontitis against fifteen of the diabetics group. In a multivariable logistic regression, periodontitis was related mainly to age and BOP. When comparing the periodontal parameters between controls and diabetics in younger (<40 years old) and older (>40 years old) subjects, the younger diabetic subjects showed significantly more plaque (p = 0.004) and inflammation (GI p < 0.001) compared with their matched controls. In the older group, gingival inflammation was markedly higher in diabetic subjects compared with controls (p = 0.003). According to the authors, this difference in the gingival health of young vs. old DM1 subjects to their matched controls may provide diagnostic advantages and prevention opportunities to exploit.

4.3. Pro-Inflammatory Mediators

After the inflammatory stimulation, the pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, interleukin-8 (IL-8), and TNF-α and other pro-inflammatory mediators like prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) and the receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand (RANKL), as well as T cell regulatory cytokines (interleukin 18- IL-18) will increase, and periodontal destruction will occur [3,17,19,23,30,35]. According to our research, there are eight studies that support that evidence [3,9,11,18,23,27,28,30]. The study by Keles et al. [30] targeted parameters such as gingival crevicular fluid IL-18 and TNF-α levels in diabetic children with gingivitis. The clinical periodontal parameters, gingival crevicular fluid IL-18 and TNF-α levels, were similar between diabetic and systemically healthy children (p > 0.05). The gingivitis subgroups showed a significantly higher PI, GI, PPD, GCF volume, and TNF-α total amounts than the healthy subgroups (p < 0.0001). However, the IL-18 concentrations were significantly higher in the periodontally healthy subgroups than in gingivitis subgroups. The TNF-α were positively correlated with PI, GI, PPD, GCF volumes, and IL-18 concentration (r = 0.552, p = 0.01; r = 0.579, p = 0.01; r = 0.534, p = 0.01, respectively). However, there was a negative correlation between the IL-18 concentration and the TNF-α (−0.524, p = 0.01). It is known that the presence of TNF-α in periodontal tissues acts as a risk factor for the beginning of alveolar bone destruction and periodontal connective tissue breakdown by increasing both secretion of matrix metalloproteinases and osteoclast formation [30,36]. The increased gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) TNF-α in DM1 children with gingivitis confirms that TNF-α is closely related to gingival inflammation [30].

The IL-18 belongs to the IL-1 superfamily and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic diseases, including DM1. According to the authors, despite of the fact that previous studies have reported that serum IL-18 levels in diabetic children were higher when compared to healthy controls, there is no evidence of the GCF IL-18 levels from diabetic and non-diabetic children [30].

In another study by Poplawska-Kita et al. [7], the GMC group showed the lowest concentration of C-Reative Protein (CRP) and TNF-α among all groups. DM1 patients with periodontitis showed higher fibrinogen (371.3 ± 114.7, p < 0.01) and TNF-α (1.6 ± 1.2, p < 0.001) concentrations, as well as lower OHI (2.1 ± 0.7, p < 0.001) and a lower number of teeth (p < 0.001). The number of sextants without signs of periodontal disease (CPI 0) was correlated negatively with fibrinogen (r = −0.272; p < 0.05) and TNF-α (r = −0.233; p < 0.05) levels. The evidence suggests that the CRP and fibrinogen are produced in response to the action of pro-inflammatory cytokines and are responsible for a systemic response [26]. The number of sextants with 4–5 mm deep pathologic pockets (CPI 3) was correlated positively with TNF-α (r = 0.348; p < 0.01) and fasting glucose level (r = 0.217; p < 0.05). Taken together, their results suggest a role for TNF-α in periodontal destruction, especially in those with poor metabolic control, and inadequate oral hygiene might contribute to the development of inflammation and further tissue destruction.

The study of Linhartov et al. [28] targeted parameters like IL-8 plasma levels in patients with DM1 and systematic health controls. According to their findings, concentrations of circulating IL-8 levels were not significantly associated with the level of glycemic control (blood glucose and HbA1c), smoking status, and clinical parameters like GI, PPD, and attachment loss (AL) (p > 0.05). However, patients with DM1 showed higher circulating IL-8 plasma levels than Health Control with Chronic Periodontitis/non-periodontitis Heath Control. The IL-8 is involved in the initiation and amplification of a severe inflammatory reaction, and it is secreted by several cell types in response to inflammatory stimuli [3,9,23,28]. Furthermore, there were statistically significant differences between the non-periodontitis healthy control in comparison to the group with Chronic Periodontitis and DM1 with chronic periodontitis concerning the GI: (0.3 ± 0.2) vs. (0.9 ± 0.3) and (1 ± 0.3), respectively (p < 0.01), and numbers of sites and teeth with a pocket depth ≥ 5 mm and attachment loss ≥ 5 mm (p < 0.01), which means that DM1 with chronic periodontitis showed a greater inflammation and clinical attachment loss that is related to periodontal destruction.

Sereti et al. [3] evaluated the GCF levels of MMP-8, IL-8, and AGEs in DM1 patients with different glycemic levels and compared them with healthy controls. The median GCF levels of MMP-8 (control: 38.3 µg/mL vs. DM1 group: 32.1 3 µg/mL, p = 0.538), IL-8 (control: 225 pg/mL vs. DM1 group: 220 pg/mL, p = 0.433), and AGEs (control: 5.8 µg/mL vs. DM1 group: 3.4 µg/mL, p = 0.905) did not differ significantly. Concerns the presence of GCF markers, no significant differences were observed between younger diabetics (<40 years old) and controls or between older diabetics (>40 years old) and controls, even when the groups were divided according to glycemic control. According to the evidence, the MMP-8 is associated with pathologic extracellular matrix destruction and is the main collagenase that is found in inflamed gingiva in adult periodontitis [3].

In another study, Lappin et al. [23] compared the circulating levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in patients with DM1 with and without periodontitis. The evidence suggests that circulating levels of IL-6 are implicated in poor clinical outcomes in DM1 and susceptibility to periodontal disease [23]. However, no difference was seen in IL-6 plasma levels between groups. On the other hand, the plasma levels of IL-8 were higher in the periodontitis group when compared to the healthy group (p < 0.001). The DM1 group and the DM1 group with periodontitis exhibited higher levels of IL-8 than healthy volunteers (p < 0.001, for both). Patients with DM1 with Periodontitis showed higher levels of IL-8 when compared to patients with periodontitis (p < 0.05).

Furthermore, Dakovic et al. [9] investigated the differences between the salivary levels of IL-8 in patients with DM1 with or without concomitant periodontitis and healthy patients. According to their findings, DM1 patients exhibited a significantly higher level of salivary IL-8 when compared to the control group (p < 0.005). However, there were no differences in the level of salivary IL-8 between DM1 patients with periodontitis and DM1 patients without periodontitis. There was a statistically significant difference for PPD, CAL, and BOP between DM1 patients with periodontitis and DM1 without periodontitis (p < 0.05). The correlation between IL-8 and clinical parameters in DM1 children did not show any statistically significant correlation.

Another aspect worth considering is the circulating levels of RANKL and osteoprotegerin (OPG) in the extent of periodontal destruction. According to the literature, the OPG and RANKL have been suggested to play an important role in the differentiation of osteoclasts and, furthermore, in periodontal-disease-associated bone loss [18]. The study by Antonoglou et al. [18] showed that DM1 patients with no or mild periodontitis had a total of 16 sites (16.4 ± 14.5) presented with bleeding and PPD ≥ 4 mm and 0.7 sites (0.7 ± 1.0) with attachment loss (AL) ≥ 4 mm. When compared to severe periodontitis, the corresponding figures were (39.6 ± 21.9) and (38.8 ± 18.5) respectively, which suggest that PPD and AL increase with the severity of periodontal disease in DM1 subjects.

The OPG was 135 pg/mL in subjects with severe periodontitis and 96.0 pg/mL in those with no or mild periodontitis. The results showed a positive association between AL ≥ 4 mm and severity of periodontitis and the level of serum OPG. However, when the analyses included only non-smokers, the positive association mentioned above showed a major drop in the strength and statistical significance. The results did not find any association between serum RANKL level or RANKL/OPG ratio and periodontal variables. The RANKL in the group of subjects with no or mild periodontitis was 18.1 pg/mL and 33.2 pg/mL for those with severe periodontitis. Concerning the RANKL/OPG ratio, the values were (0.2 ± 0.1) for the first group (no or mild periodontitis) and (0.1 ± 0.1) for those with severe periodontitis. According to their study, the serum OPG, which is a marker of systemic inflammatory burden, could also be an indicator of periodontal tissue destruction in DM1 subjects [18].

When evaluating the quality of the studies, using the Joanna Briggs method, most of them were classified as high or moderate score quality. The item that presented the worst results was the “strategies to deal with confounding factors state”, with many of them not presenting such cofactors such as tobacco habits. Unfortunately, there are no other systematic review to our knowledge to make a comparison to our results regarding the quality of the studies (or existence of bias).

Our systematic review found that the interplay between the two conditions highlights the importance of the need for a good communication between the endocrinologist and dentist about diabetic patients, always considering the probability that the two diseases may occur simultaneously in order to ensure the early diagnosis of both.

We acknowledge some limitations in our systematic review, firstly related with the few existing original articles suitable for inclusion (such as randomized controlled trials), or lack of information that could been used for a quantitative analysis. For these reasons, a meta-analysis was not possible. Nevertheless, this study, to our knowledge, is an original systematic review of the existing data regarding the association between DM1 and PD.

5. Conclusions

Most of the studies confirm the association between DM1 and PD. The prevalence and severity of PD was higher in DM1 patients when compared to healthy subjects.

Periodontal disease was associated with glucose variability in DM1 patients. Furthermore, an increased periodontal inflammatory tendency corresponded to those individuals with poor metabolic control. DM1 subjects with increased HbA1c levels were associated with an increase in plaque index, gingival index, probing depths > 3 mm, and clinical attachment loss when compared to healthy subjects. According to some studies, longer durations of DM were associated with greater periodontal attachment loss.

In addition, subjects with DM1 showed higher levels of IL-8, TNF-α, CPR, and fibrinogen. However, the findings of this review showed that research having a prospective longitudinal design should be done to clarify the roles of the pro-inflammatory cytokines in periodontal disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C., L.M. and M.R.; methodology, R.C., P.L.-J., L.M. and M.R.; software, F.C.; formal analysis, R.C., F.C., L.M. and M.R.; investigation, R.C. and M.R.; resources, R.C., F.C. and M.R.; data curation, L.M. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., L.M. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, R.C., F.C., L.M., B.R.-C. and M.R.; visualization P.L.-J. and B.R.-C.; supervision, M.R.; project administration and funding acquisition, L.M. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University Institute of Health Sciences (IUCS-CESPU) with the participation of Marta Relvas, funded by the project grant ADMT1PD_GI2-CESPU_2022, and Luis Monteiro, funded by the project grant mTORORAL_GI2-CESPU_2022 from CESPU University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Xiao, E.; Graves, D.T. Diabetes mellitus related bone metabolism and periodontal disease. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 72, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Gopalkrishna, P. Type 1 diabetes and periodontal disease: A literature review. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 56, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sereti, M.; Roy, M.; Zekeridou, A.; Gastaldi, G.; Giannopoulou, C. Gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers in type 1 diabetes mellitus: A case–control study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2021, 7, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, D.T.; Ding, Z.; Yang, Y. The impact of diabetes on periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 2020, 82, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, K.; Arangannal, P.; Santoshkumari. Frequency of putative periodontal pathogens among type 1 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daković, D.; Mileusnić, I.; Hajduković, Z.; Čakić, S.; Hadži-Mihajlović, M. Gingivitis and Periodontitis in children and adolescents suffering from type 1 diabetes mellitus. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2015, 72, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popławska-Kita, A.; Siewko, K.; Szpak, P.; Król, B.; Telejko, B.; Klimiuk, P.A.; Stokowska, W.; Górska, M.; Szelachowska, M. Association between type 1 diabetes and periodontal health. Adv. Med. Sci. 2014, 59, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajita, M.; Karan, P.; Vivek, G.; Anand, M.S.; Anuj, M. Periodontal disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus: Associations with glycemic control and complications: An Indian perspective. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2013, 7, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakovic, D.; Colic, M.; Cakic, S.; Mileusnic, I.; Hajdukovic, Z.; Stamatovic, N. Salivary interleukin-8 levels in children suffering from Type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2013, 37, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adda, G.; Aimetti, M.; Citterio, F.; Consoli, A.; Di Bartolo, P.; Landi, L.; Lione, L.; Luzi, L. Consensus report of the joint workshop of the Italian Society of Diabetology, Italian Society of Periodontology and Implantology, Italian Association of Clinical Diabetologists (SID-SIdP-AMD). Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 2515–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicembrini, I.; Barbato, L.; Serni, L.; Caliri, M.; Pala, L.; Cairo, F.; Mannucci, E. Glucose variability and periodontal disease in type 1 diabetes: A cross-sectional study—The “PAROdontopatia e DIAbete” (PARODIA) project. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, B.; Park, B.; Bartold, P.M. Periodontitis and type II diabetes: A two-way relationship. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2013, 11, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, C.; João, M.F.D.; Camargo, G.A.D.C.G.; Teixeira, G.S.; Machado, T.S.; Azevedo, R.D.S.; Mariano, F.S.; Colombo, N.H.; Vizoto, N.L.; Mattos-Graner, R.D.O. Microbiological, lipid and immunological profiles in children with gingivitis and type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2017, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, F.Q.; Almeida-da-Silva, C.L.C.; Huynh, B.; Trinh, A.; Liu, J.; Woodward, J.; Asadi, H.; Ojcius, D.M. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed. J. 2019, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda-Sobczak, A.; Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz, D.; Wyganowska-Swiatkowska, M. Type 1 Diabetes and Periodontal Health. Clin. Ther. 2018, 40, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sima, C.; Glogauer, M. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2013, 13, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şurlin, P.; Oprea, B.; Solomon, S.M.; Popa, S.G.; Moţa, M.A.R.I.A.; Mateescu, G.O.; Rauten, A.M.; Popescu, D.M.; Dragomir, L.P.; Puiu, I.; et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-7,-8,-9 and-13 in gingival tissue of patients with type 1 diabetes and periodontitis. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2014, 55, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Antonoglou, G.; Knuuttila, M.; Nieminen, P.; Vainio, O.; Hiltunen, L.; Raunio, T.; Niemelä, O.; Hedberg, P.; Karttunen, R.; Tervonen, T. Serum osteoprotegerin and periodontal destruction in subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Alba, A.L.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Konstantinidis, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Taylor, R. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.T.; Chen, S.C.; Lin, C.L.; Hsu, J.T.; Chen, I.A.; Wu, I.T.; Palanisamy, K.; Shen, T.C.; Li, C.Y. The association between Type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI’s Systematic Reviews: Study selection and critical appraisal. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappin, D.F.; Robertson, D.; Hodge, P.; Treagus, D.; Awang, R.A.; Ramage, G.; Nile, C.J. Evaluation of Serum Glycated Haemoglobin, IL-6, IL-8 and CXCL5 in TIDM with and without Periodontitis and Effects of Advanced Glycation End Products and Porphyromonas Gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide on IL-6, IL-8 and CXCL5 Expression by Oral Epithelial Cell. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.F.; McGrath, C.P.; Yiu, C.K.Y. Oral health status of children with type 1 diabetes: A comparative study. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 30, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Gastaldi, G.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Mombelli, A.; Giannopoulou, C. Periodontal health in a cohort of subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2019, 5, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E.D.; Selway, C.A.; Allen, G.; Bednarz, J.; Weyrich, L.S.; Gue, S.; Peña, A.S.; Couper, J. Early markers of periodontal disease and altered oral microbiota are associated with glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2021, 22, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zizzi, A.; Tirabassi, G.; Aspriello, S.D.; Piemontese, M.; Rubini, C.; Lucarini, G. Gingival advanced glycation end-products in diabetes mellitus-associated chronic periodontitis: An immunohistochemical study. J. Periodontal. Res. 2013, 48, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borilova Linhartova, P.; Kavrikova, D.; Tomandlova, M.; Poskerova, H.; Rehka, V.; Dušek, L.; Izakovicova Holla, L. Differences in interleukin-8 plasma levels between diabetic patients and healthy individuals independently on their periodontal status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.; Parihar, A.S.; Sood, M.; Singh, P.; Singh, N. Relationship between severity of periodontal disease and control of diabetes (glycated hemoglobin) in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Int. Oral Health 2015, 7, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, S.; Anik, A.; Cevik, O.; Abas, B.I.; Anik, A. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of interleukin-18 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in type 1 diabetic children with gingivitis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 3623–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Bhattacharjee, K.; Chakraborty, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Ghosh, S. Periodontal disease in type 1 diabetes mellitus: Influence of pubertal stage and glycemic control. Endocr. Pract. 2021, 27, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis:Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S173–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascones-Martínez, A.; Muñoz-Corcuera, M.; Bascones-Ilundain, J. Diabetes y periodontitis: Una relación bidireccional [Diabetes and periodontitis: A bidirectional relationship]. Med. Clin. 2015, 145, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babatzia, A.; Papaioannou, W.; Stavropoulou, A.; Pandis, N.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Papagiannoulis, L.; Gizani, S. Clinical and microbial oral health status in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Int. Dent. J. 2020, 70, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Ceriello, A.; Buysschaert, M.; Chapple, I.; Demmer, R.T.; Graziani, F.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Lione, L.; Madianos, P.; et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 137, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Mishra, L.; Mohanty, R.; Nayak, R. Diabetes and gum disease: The diabolic duo. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2014, 8, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).