Patterns of Opioid and Non-Opioid Analgesic Consumption in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Conditions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Survey

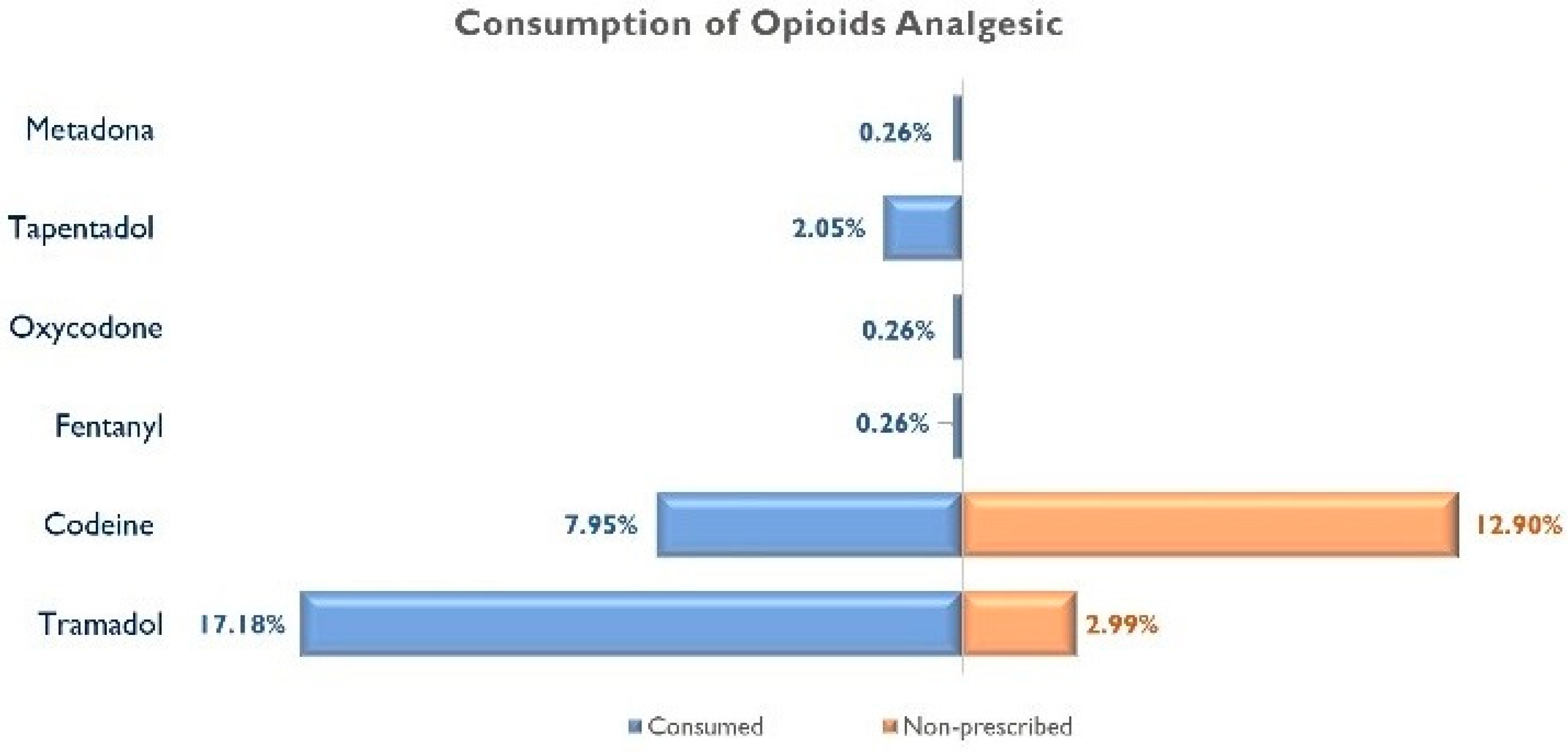

- Have you taken opioid analgesics prescribed by a medical doctor within the last 30 days? Participants answering “Yes” marked the type of opioid analgesic by using their commercial names: Tramadol, codeine, Fentanyl, Oxycodone, Morphine, Pethidine, Buprenorphine, Hydromorphone, Tapentadol, or Methadone;

- Have you taken non-opioid analgesics prescribed by a medical doctor within the last 30 days? Participants answering “Yes” marked the type of non-opioid analgesic by using their commercial names, including Paracetamol, ibuprofen, metamizole, or Acetylsalicylic acid.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, P.; Qie, S.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J.; Li, K.; Xi, J. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A single arm meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaffi, J.; Meliconi, R.; Ruscitti, P.; Berardicurti, O.; Giacomelli, R.; Ursini, F. Rheumatic manifestations of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2020, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullahi, A.; Candan, S.A.; Abba, M.A.; Bello, A.H.; Alshehri, M.A.; Afamefuna Victor, E.; Umar, N.A. Kundakci B Neurological and musculoskeletal features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caronna, E.; Pozo-Rosich, P. Headache as a symptom of COVID-19: Narrative review of 1-year research. Curr. Pain. Headache Rep. 2021, 25, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Filho, P.A.S. Headache associated with COVID-19: Epidemiology, characteristics, pathophysiology and management. Headache 2022, 62, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Florencio, L.L.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Navarro-Santana, M. Prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms in hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Int. Med. 2021, 92, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global prevalence of post COVID-19 condition or long COVID: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, jiac136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. Long COVID: Current definition. Infection 2022, 50, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Navarro-Santana, M.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Time course prevalence of post-COVID pain symptoms of musculoskeletal origin in patients who had survived severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2022, 163, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Norrefalk, J.R.; Borg, K. Pain burden in post-COVID-19 syndrome following mild COVID-19 infection. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; de-la-Llave-Rincón, A.I.; Ortega-Santiago, R.; Ambite-Quesada, S.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arias-Navalón, J.A.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Martín-Guerrero, J.D.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of musculoskeletal pain symptoms as long-term post-COVID sequelae in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: A multicenter study. Pain 2022, 163, e989–e996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Navarro-Santana, M.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Cuadrado, M.L.; García-Azorín, D.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Plaza-Manzano, G. Headache as an acute and post-COVID-19 symptom in COVID-19 survivors: A meta-analysis of the current literature. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 3820–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premraj, L.; Kannapadi, N.V.; Briggs, J.; Seal, S.M.; Battaglini, D.; Fanning, J.; Suen, J.; Robba, C.; Fraser, J.; Cho, S.M. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 434, 120162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.S.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H.; Nirantharakumar, K.; et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Mattiuzzi, C. Internet searches for over-the-counter analgesics during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in Italy. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1885–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, T.P.; Do, H.Q. Internet search interest for over-the-counter analgesics during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 2407–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, A.A.; Conger, A.; McCormick, Z.L.; Kendall, R.W.; Wagner, G.; Teramoto, M.; Cushman, D.M. Changes in interventional pain physician decision-making, practice patterns, and mental health during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 Global Pandemic. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 3585–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Yang, K.C.; Kaminski, P.; Peng, S.; Odabas, M.; Gupta, S.; Green, H.D., Jr.; Ahn, Y.Y.; Perry, B.L. Substitution of nonpharmacologic therapy with opioid prescribing for pain during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021, 4, e2138453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Utilización de Medicamentos Opioides en España. 2021. Available online: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/observatorio-de-uso-de-medicamentos/utilizacion-de-medicamentos-opioides-en-espana/ (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Utilización de Medicamentos Analgésicos No Opioides en España. 2021. Available online: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/observatorio-de-uso-de-medicamentos/utilizacion-de-medicamentos-analgesicos-no-opioides-en-espana/ (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Mirahmadizadeh, A.; Heiran, A.; Dadvar, A.; Moradian, M.J.; Sharifi, M.H.; Sahebi, R. The association of opium abuse with mortality amongst hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Iranian Population. J. Prev. 2022, 43, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, J.M.; Schnell, M.K.; Schwandt, H.; Zhang, J. Prescribing of Opioid Analgesics and Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021, 4, e216147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, C.J.; Campbell, C.M.; McGill, L.S.; Wegener, S.T.; Aaron, R.V. Trajectories and Individual Differences in Pain, Emotional Distress, and Prescription Opioid Misuse During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A One-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Pain 2022, 23, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb, C.T.; Goepp, M.; Rossi, A.G.; Yao, C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prostaglandins, and COVID-19. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 4899–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, P. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 368, m1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, C.G.; Varisco, T.J.; Bapat, S.S.; Shen, C.; Thornton, J.D. Impact of COVID-19 related policy changes on filling of opioid and benzodiazepine medications. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2005–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosetti, C.; Santucci, C.; Radrezza, S.; Erthal, J.; Berterame, S.; Corli, O. Trends in the consumption of opioids for the treatment of severe pain in Europe, 1990-2016. Eur. J. Pain 2019, 23, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS.GOV/OPIOIDS. What Is the U.S. Opioid Epidemic? Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Canadian Centre of Substance Use and Addiction. Prescription Opioids 2020. (Canadian Drug Summary). Available online: https://www.ccsa.ca/prescription-opioids-canadian-drug-summary (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Kalkman, G.A.; Kramers, C.; van Dongen, R.T.; van den Brink, W.; Schellekens, A. Trends in use and misuse of opioids in the Netherlands: A retrospective, multi- source database study. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e498–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, A.E.; Clausen, T.; Sjøgren, P.; Odsbu, I.; Skurtveit, S. Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017. Scand J. Pain 2019, 19, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanicki, J.L.; Schwarz, J.; May, K.P.; Black, J.C.; Dart, R.C. Tramadol non-medical use in Four European countries: A comparative analysis. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2020, 217, 108367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reines, S.A.; Goldmann, B.; Harnett, M.; Lu, L. Misuse of Tramadol in the United States: An Analysis of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health 2002–2017. Subst. Abuse 2020, 14, 1178221820930006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigal, L.M.; Bibeau, K.; Dunbar, S. Tramadol Prescription over a 4-Year Period in the USA. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2019, 23, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.S.; Bergin, M.; Van Hout, M.C.; McGuinness, P.; De Pleissisc, J.; Rich, E.; Dada, S.; Wells, R.; Gooney, M.A. Purchasing Over The Counter (OTC) Medicinal Products Containing Codeine—Easy Access, Advertising, Misuse and Perceptions of Medicinal Risk. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 21, 30049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrilla, J.A.; de Lorenzo, Í.; Sastre, M.; Díaz de Terán, J. Headache as a cardinal symptom of coronavirus disease 2019 a cross-sectional study. Headache 2020, 60, 2176–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nino-Orrego, M.J.; Baracaldo-Santamaría, D.; Patricia Ortiz, C.; Zuluaga, H.P.; Cruz-Becerra, S.A.; Soler, F.; Pérez-Acosta, A.M.; Delgado, D.R.; Calderon-Ospina, C.A. Prescription for COVID-19 by non-medical professionals during the pandemic in Colombia: A cross-sectional study. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2022, 13, 20420986221101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, O.; Borchgrevink, P.C.; Fredheim, O.M.; Mahic, M.; Romundstad, P.; Skurtveit, S. Prevalence of use of non-prescription analgesics in the Norwegian HUNT3 population: Impact of gender, age, exercise and prescription of opioids. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, E.; Fernández-Cerezo, F.L.; Díaz-Jimenez, J.; Rosety-Rodriguez, M.; Díaz, A.J.; Ordonez, F.J.; Rosety, M.Á.; Rosety, I. Consumption of over-the-Counter Drugs: Prevalence and Type of Drugs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilet-Rosell, E.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Sáez, J.F.; Alvarez-Dardet, C. Inequality in analgesic prescription in Spain. A gender development issue. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsen, P.J.; Svendsen, K.; Wilsgaard, T.; Stubhaug, A.; Nielsen, C.S.; Eggen, A.E. Persistent analgesic use and the association with chronic pain and other risk factors in the population-a longitudinal study from the Tromsø Study and the Norwegian Prescription Database. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Dal Pizzol, T.; Turmina Fontanella, A.; Cardoso Ferreira, M.B.; Bertoldi, A.D.; Boff Borges, R.; Serrate Mengue, S. Analgesic use among the Brazilian population: Results from the National Survey on Access, Use and Promotion of Rational Use of Medicines (PNAUM). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol-Prokopczyk, H. Use and Opinions of Prescription Opioids Among Older American Adults: Sociodemographic Predictors. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Cancela-Cilleruelo, I.; Moro-López-Menchero, P.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Torres-Macho, J.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; Martín-Guerrero, J.D.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Post-COVID Pain in Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors Depending on Infection with the Historical, Alpha or Delta SARS-CoV-2. Var. Biomed. 2022, 10, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 594, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherrer, J.F.; Miller-Matero, L.R.; Salas, J.; Sullivan, M.D.; Secrest, S.; Autio, K.; Wilson, L.; Amick, M.; De Bar, L.; Lustman, P.J.; et al. Characteristics of Patients with Non-Cancer Pain and Perceived Severity of COVID-19 Related Stress. Mo. Med. 2022, 119, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, A.S.; Ghani, S.B.; Naps, M.; Grandner, M.A.; Stein, M.D.; Chakravorty, S. Past year use or misuse of an opioid is associated with use of a sedative-hypnotic medication: A NSDUH study. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 18, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, S.A.; Raji, M.A.; Chen, L.; Kuo, Y.F. Trends in the Use of Benzodiazepines, Z-Hypnotics, and Serotonergic drugs among US women and men before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2131012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeisler, M.É.; Lane, R.I.; Wiley, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A.; Howard, M.E.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W. Follow-up survey of US adult reports of mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic, September 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Al-Aly, Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with COVID-19: Cohort study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostinelli, E.G.; Smith, K.; Zangani, C.; Ostacher, M.J.; Lingford-Hughes, A.R.; Hong, J.S.W.; Macdonald, O.; Cipriani, A. COVID-19 and substance use disorders: A review of international guidelines for frontline healthcare workers of addiction services. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschert, C.; Seitz, N.N.; Olderbak, S.; Pogarell, O.; Dreischulte, T.; Kraus, L. Abuse of Non-opioid Analgesics in Germany: Prevalence and Associations Among Self-Medicated Users. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 864389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 74 | 18.97 |

| Female | 316 | 81.03 |

| Age group | ||

| <40 years | 66 | 17.28 |

| 40–55 years | 242 | 63.35 |

| >55 years | 74 | 19.37 |

| Nationality | ||

| Immigrants | 6 | 1.54 |

| Spanish | 384 | 98.46 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 121 | 31.03 |

| Married or couple | 208 | 53.33 |

| Divorced/widow | 54 | 13.85 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary school | 18 | 4.62 |

| Secondary school | 111 | 28.46 |

| Higher education | 261 | 66.92 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Employed | 202 | 51.79 |

| Unemployed | 41 | 10.51 |

| Inactive | 95 | 24.36 |

| Monthly income | ||

| <EUR 1000 | 29 | 7.44 |

| EUR 1000–EUR 2000 | 129 | 33.08 |

| >EUR 2000 | 189 | 48.46 |

| Alcohol consumption in the past 12 months | ||

| No | 189 | 48.46 |

| Yes | 201 | 51.54 |

| Smoking habit in the past 12 months | ||

| Smoker | 35 | 8.97 |

| Ex-smoker | 164 | 42.05 |

| Non-smoker | 191 | 48.97 |

| Pain symptoms (generalized, headache, and chest pain) | ||

| No | 28 | 7.18 |

| Yes | 362 | 92.82 |

| Number of chronic conditions | ||

| 0 | 111 | 28.46 |

| 1–2 | 121 | 31.03 |

| ≥3 | 158 | 40.51 |

| Number of post-COVID symptoms | ||

| <5 | 86 | 22.05 |

| 5–7 | 171 | 43.85 |

| >7 | 133 | 34.10 |

| Self-assessment of health status | ||

| Good | 106 | 27.18 |

| Poor | 173 | 44.36 |

| Very poor | 111 | 28.46 |

| Hospitalization in preceding 12 months | ||

| No | 283 | 72.56 |

| Yes | 107 | 27.44 |

| Admission to intensive care in preceding 12 months | ||

| No | 376 | 96.41 |

| Yes | 14 | 3.59 |

| Opioid Analgesic consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | 296 | 75.90 |

| Yes | 94 | 24.10 |

| Non-opioid analgesics consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | 69 | 17.69 |

| Yes | 321 | 82.31 |

| Anxiolytic consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | 215 | 55.13 |

| Yes | 175 | 44.87 |

| Antidepressant consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | 237 | 60.77 |

| Yes | 153 | 39.23 |

| Cannabis, Marijuana, or Hashish consumption in the last 12 months | ||

| No | 374 | 95.9 |

| Yes | 16 | 4.10 |

| Opioid Analgesic | Non-Opioid Analgesic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (95% CI) | p Value | N | % (95% CI) | * p Value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 12 | 16.22 (9.18, 25.83) | 0.078 | 54 | 72.97 (62.12, 82.07) | 0.019 * |

| Female | 82 | 25.95 (21.35, 30.99) | 267 | 84.49 (80.20, 88.16) | ||

| Age group | ||||||

| < 40 years | 9 | 13.64 (6.97, 23.41) | 0.095 | 45 | 68.18 (56.35, 78.46) | 0.005 * |

| 40–55 years | 64 | 26.45 (21.19, 32.26) | 206 | 85.12 (80.23, 89.18) | ||

| >55 years | 18 | 24.32 (15.66, 34.95) | 63 | 85.14 (75.75, 91.84) | ||

| Nationality | ||||||

| Immigrants | 1 | 16.67 (1.86, 55.81) | 0.668 | 6 | 100 (100.00, 100.00) | 0.252 |

| Spanish | 93 | 24.22 (20.14, 28.69) | 315 | 82.03 (77.96, 85.62) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 16 | 13.22 (8.08, 20.10) | 0.005 * | 90 | 74.38 (66.09, 81.52) | 0.036 * |

| Married or couple | 59 | 28.37 (22.57, 34.76) | 178 | 85.58 (80.32, 89.85) | ||

| Divorced/widow | 18 | 33.33 (21.88, 46.52) | 46 | 85.19 (73.98, 92.74) | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Primary school | 4 | 22.22 (8.00, 44.58) | 0.000 * | 14 | 77.78 (55.42, 92.00) | 0.144 |

| Secondary school | 42 | 37.84 (29.22, 47.08) | 98 | 88.29 (81.34, 93.27) | ||

| Higher education | 48 | 18.39 (14.05, 23.43) | 209 | 80.08 (74.92, 84.58) | ||

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Employed | 44 | 21.78 (16.52, 27.85) | 0.243 | 165 | 81.68 (75.92, 86.55) | 0.786 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 24.39 (13.29, 38.97) | 34 | 82.93 (69.38, 92.02) | ||

| Inactive | 30 | 31.58 (22.89, 41.37) | 81 | 85.26 (77.12, 91.30) | ||

| Monthly income | ||||||

| <EUR 1000 | 12 | 41.38 (24.97, 59.41) | 0.001 * | 26 | 89.66 (74.90, 97.00) | 0.652 |

| EUR 1000–EUR 2000 | 43 | 33.33 (25.64, 41.77) | 107 | 82.95 (75.76, 88.67) | ||

| >EUR 2000 | 32 | 16.93 (12.11, 22.76) | 152 | 80.42 (74.33, 85.59) | ||

| Alcohol consumption in the past 12 months | ||||||

| No | 40 | 21.16 (15.81, 27.40) | 0.188 | 151 | 79.89 (73.75, 85.13) | 0.226 |

| Yes | 54 | 26.87 (21.1, 33.29) | 170 | 84.58 (79.11, 89.06) | ||

| Smoking habit in the past 12 months | ||||||

| Smoker | 7 | 20.00 (9.42, 35.31) | 0.199 | 29 | 82.86 (68.03, 92.51) | 0.077 |

| Ex-smoker | 47 | 28.66 (22.16, 35.91) | 143 | 87.20 (81.44, 91.65) | ||

| Non-smoker | 40 | 20.94 (15.63, 27.12) | 149 | 78.01 (71.74, 83.44) | ||

| Pain symptoms (generalized, headache, and chest pain) | ||||||

| No | 5 | 17.86 (7.16, 34.80) | 0.422 | 18 | 64.29 (45.84, 79.94) | 0.009 * |

| Yes | 89 | 24.59 (20.36, 29.21) | 303 | 83.7 (79.64, 87.23) | ||

| Number of chronic conditions | ||||||

| None | 22 | 19.82 (13.23, 27.96) | 0.377 | 87 | 78.38 (70.05, 85.25) | 0.002 * |

| 1–2 | 29 | 23.97 (17.04, 32.13) | 91 | 75.21 (66.98, 82.24) | ||

| ≥3 | 43 | 27.22 (20.73, 34.52) | 143 | 90.51 (85.20, 94.35) | ||

| Number of post-COVID symptoms | ||||||

| <5 | 12 | 13.95 (7.86, 22.42) | 0.000 * | 69 | 80.23 (70.90, 87.57) | 0.000 * |

| 5–7 | 35 | 20.47 (14.95, 26.98) | 129 | 75.44 (68.60, 81.43) | ||

| >7 | 47 | 35.34 (27.60, 43.71) | 123 | 92.48 (87.07, 96.07) | ||

| Self-assessment of health status | ||||||

| Good | 20 | 18.87 (12.31, 27.10) | 0.229 | 86 | 81.13 (72.90, 87.69) | 0.018 |

| Poor | 42 | 24.28 (18.35, 31.06) | 152 | 87.86 (82.38, 92.09) | ||

| Very poor | 32 | 28.83 (21.03, 37.72) | 83 | 74.77 (66.13, 82.15) | ||

| Hospitalization in preceding 12 months | ||||||

| No | 65 | 22.97 (18.36, 28.13) | 0.394 | 229 | 80.92 (76.04, 85.17) | 0.242 |

| Yes | 29 | 27.10 (19.37, 36.05) | 92 | 85.98 (78.48, 91.57) | ||

| Admission to intensive care in preceding 12 months | ||||||

| No | 91 | 24.20 (20.08, 28.72) | 0.812 | 309 | 82.18 (78.07, 85.79) | 0.734 |

| Yes | 3 | 21.43 (6.43, 46.90) | 12 | 85.71 (61.51, 96.91) | ||

| Opioid Analgesic consumption in the past 30 days | ||||||

| No | N.A. | 232 | 78.38 (73.43, 82.78) | 0.000 * | ||

| Yes | 89 | 94.68 (88.74, 97.94) | ||||

| Non-opioid analgesic consumption in the past 30 days | ||||||

| No | 5 | 7.25 (2.82, 15.15) | 0.000 * | N.A. | ||

| Yes | 89 | 27.73 (23.04, 32.81) | ||||

| Anxiolytic consumption in the past 30 days | ||||||

| No | 35 | 16.28 (11.81, 21.65) | 0.000 * | 162 | 75.35 (69.28, 80.74) | 0.000 * |

| Yes | 59 | 33.71 (27.02, 40.94) | 159 | 90.86 (85.92, 94.46) | ||

| Antidepressant consumption in the past 30 days | ||||||

| No | 48 | 20.25 (15.52, 25.71) | 0.027 * | 185 | 78.06 (72.47, 82.97) | 0.006 * |

| Yes | 46 | 30.07 (23.22, 37.65) | 136 | 88.89 (83.19, 93.14) | ||

| Cannabis, Marijuana, or Hashish consumption in the last 12 months | ||||||

| No | 90 | 24.06 (19.94, 28.59) | 0.932 | 308 | 82.35 (78.25, 85.96) | 0.916 |

| Yes | 4 | 25.00 (9.08, 49.07) | 13 | 81.25 (57.92, 94.42) | ||

| Opioid Analgesic | Non-Opioid Analgesic | |

|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.65 (0.76, 3.57) | 2.20 (1.15, 4.22) |

| Age group | ||

| <40 years | Reference | Reference |

| 40–55 years | 1.84 (0.77, 4.39) | 3.30 (1.65, 6.60) |

| >55 years | 1.49 (0.54, 4.12) | 3.30 (1.34, 8.09) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | Reference | Reference |

| Married or couple | 2.96 (1.43, 6.12) | N.S. |

| Divorced/widow | 2.13 (0.86, 5.28) | N.S. |

| Monthly income | ||

| >EUR 2000 | Reference | Reference |

| EUR 1000–EUR 2000 | 2.90 (1.59, 5.26) | N.S. |

| <EUR 1000 | 3.81 (1.37, 10.61) | N.S. |

| Number of post-COVID symptoms | ||

| <5 | Reference | Reference |

| 5–7 | 1.36 (0.62, 2.97) | N.S. |

| >7 | 2.64 (1.18, 5.87) | N.S. |

| Anxiolytic consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.85 (1.05, 3.25) | 2.61 (1.36, 4.98) |

| Opioid Analgesic consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | N.A. | Reference |

| Yes | 3.41 (1.27, 6.11) | |

| Non-opioid analgesic consumption in the past 30 days | ||

| No | Reference | N.A. |

| Yes | 2.70 (0.99, 7.35) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; Gallardo-Pino, C.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. Patterns of Opioid and Non-Opioid Analgesic Consumption in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Conditions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206586

Carrasco-Garrido P, Palacios-Ceña D, Hernández-Barrera V, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Gallardo-Pino C, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Patterns of Opioid and Non-Opioid Analgesic Consumption in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Conditions. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(20):6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206586

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrasco-Garrido, Pilar, Domingo Palacios-Ceña, Valentín Hernández-Barrera, Isabel Jiménez-Trujillo, Carmen Gallardo-Pino, and Cesar Fernández-de-las-Peñas. 2023. "Patterns of Opioid and Non-Opioid Analgesic Consumption in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Conditions" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 20: 6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206586

APA StyleCarrasco-Garrido, P., Palacios-Ceña, D., Hernández-Barrera, V., Jiménez-Trujillo, I., Gallardo-Pino, C., & Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. (2023). Patterns of Opioid and Non-Opioid Analgesic Consumption in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Conditions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(20), 6586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206586