Suicide among Cancer Patients: Current Knowledge and Directions for Observational Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction

3. Results

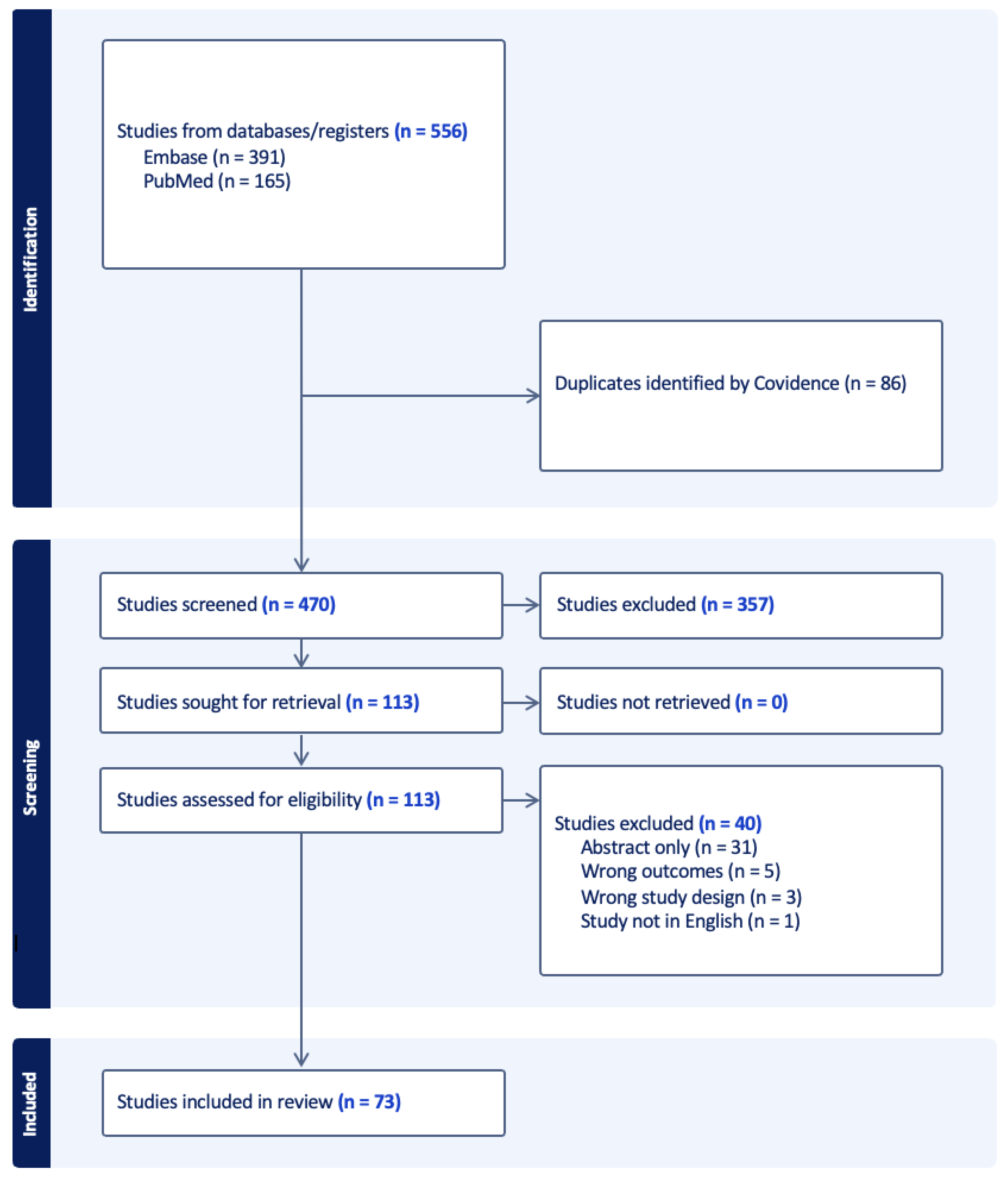

Search Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, F.B.; Cisewski, J.A.; Xu, J.; Anderson, R.N. Provisional Mortality Data—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New Approaches and Procedures for Cancer Treatment: Current Perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211034366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Zhang, Y.; Tuanquin, L.; Bluethmann, S.M.; Park, H.S.; Chinchilli, V.M. Suicide among Cancer Patients. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Li, J.-Q.; Shi, J.-F.; Que, J.-Y.; Liu, J.-J.; Lappin, J.M.; Leung, J.; Ravindran, A.V.; Chen, W.-Q.; Qiao, Y.-L.; et al. Depression and Anxiety in Relation to Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Park, E.-C.; Kim, T.H.; Han, E. Mental Disorders and Suicide Risk among Cancer Patients: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022, 26, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ma, J.; Jemal, A.; Zhao, J.; Nogueira, L.; Ji, X.; Yabroff, K.R.; Han, X. Suicide Risk among Individuals Diagnosed with Cancer in the US, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2251863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, R.; Hong, Y.-R.; Wasserman, R.M.; Swint, J.M.; Azenui, N.B.; Sonawane, K.B.; Tsai, A.C.; Deshmukh, A.A. Analysis of Suicide after Cancer Diagnosis by US County-Level Income and Rural vs Urban Designation, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2129913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lyu, J.; Yang, B.; Yan, T.; Ma, Q.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, H. Incidence and Risk Factors of Suicide among Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: A Population-Based Analysis from 2000 to 2018. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 972908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lin, H.; Xu, F.; Liu, J.; Cai, Q.; Yang, F.; Lv, L.; Jiang, Y. Risk Factors Associated with Suicide among Esophageal Carcinoma Patients from 1975 to 2016. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, N.J.; Talukder, A.M.; Lawson, A.G.; Komic, A.X.; Bateson, B.P.; Jones, A.J.; Kruse, E.J. Thyroid Malignancy and Suicide Risk: An Analysis of Epidemiologic and Clinical Factors. World J. Endocr. Surg. 2018, 10, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, A.B.; Li, E.V.; Desai, A.S.; Press, D.J.; Schaeffer, E.M. Cause of Death during Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Contemporary, US Population-Based Analysis. Cancer 2021, 127, 2895–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, Z.; DiBianco, J.M.; Jen, R.P.; Harper, B.; Yaguchi, G.; Reinstatler, L.; Woodard, C.; Moses, K.A.; Terris, M.K.; Madi, R. The Impact of Radical Cystectomy and Urinary Diversion on Suicidal Death in Patients with Bladder Cancer. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2016, 43, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, Z.; Goldberg, H.; Chandrasekar, T.; Arora, K.; Sayyid, R.K.; Hamilton, R.J.; Fleshner, N.E.; Williams, S.B.; Wallis, C.J.D.; Kulkarni, G.S. Changing Trends for Suicidal Death in Patients with Bladder Cancer: A 40+ Year Population-Level Analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2018, 16, 206–212.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.-D.; Chen, W.-K.; Wu, C.-Y.; Wu, W.-T.; Xin, X.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Li, P.; Zhang, M.-H. Cause of Death during Renal Cell Carcinoma Survivorship: A Contemporary, Population-Based Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 864132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, Z.; Jen, R.P.; DiBianco, J.M.; Dominica, R.; Reinstatler, L.; Li, Q.; Madi, R.; Lewis, R.W.; Smith, A.M.; Neal, D.E., Jr.; et al. Factors Associated with Suicide in Patients with Genitourinary Malignancies. J. Urol. 2015, 193, e105–e106. [Google Scholar]

- Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Simpson, M.C.; Zhao, L.; Boakye, E.A.; Olomukoro, S.I.; Varvares, M.A. Suicide Risk among Cancer Survivors: Head and Neck versus Other Cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 124, 4072–4079. [Google Scholar]

- Kam, D.; Salib, A.; Gorgy, G.; Patel, T.D.; Carniol, E.T.; Eloy, J.A.; Baredes, S.; Park, R.C. Incidence of Suicide in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 141, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, S.T.; Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Christopher, K.M.; Arnold, L.D.; Schootman, M.; Walker, R.J.; Varvares, M.A. Competing Causes of Death in the Head and Neck Cancer Population. Oral. Oncol. 2017, 65, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Simpson, M.C.; Bukatko, A.R.; Boakye, E.A. The Association of Marital Status with Suicide among Male Cancer Patients in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, M.B.; Walsh, N.J.; Jones, A.J.; Talukder, A.M.; Lawson, A.G.; Kruse, E.J. Demographic and Clinical Factors Associated with Suicide in Gastric Cancer in the United States. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, A.; Kunieda, E. Suicide in Patients with Gastric Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 46, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshanbary, A.A.; Zaazouee, M.S.; Hasan, S.M.; Abdel-Aziz, W. Risk Factors for Suicide Mortality and Cancer-Specific Mortality among Patients with Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A SEER Based Study. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 2067–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhao, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Hong, S.; Huang, Y.; et al. Trends in Incidence and Associated Risk Factors of Suicide Mortality in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4146–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, D.; Rao, A.; Bressel, M.; Neiger, D.; Solomon, B.; Mileshkin, L. Suicide in Lung Cancer: Who Is at Risk? Chest 2013, 144, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitanidis, A.; Alevizakos, M.; Pitiakoudis, M.; Wiggins, D. Trends in Incidence and Associated Risk Factors of Suicide Mortality among Breast Cancer Patients. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, K.K.; Roncancio, A.M.; Plaxe, S.C. Women with Gynecologic Malignancies Have a Greater Incidence of Suicide than Women with Other Cancer Types. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2013, 43, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdi, H.; Swensen, R.E.; Munkarah, A.R.; Chiang, S.; Luhrs, K.; Lockhart, D.; Kumar, S. Suicide in Women with Gynecologic Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 122, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hu, X.; Zhao, J.; Ma, J.; Jemal, A.; Yabroff, K.R. Trends of Cancer-Related Suicide in the United States: 1999–2018. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.P.; Mehta, V.; Branovan, D.; Huang, Q.; Schantz, S.P. Non-Cancer-Related Deaths from Suicide, Cardiovascular Disease, and Pneumonia in Patients with Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Squamous Carcinoma. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 138, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahouma, M.; Kamel, M.; Nasar, A.; Harrison, S.; Lee, B.; Stiles, B.; Altorki, N.; Port, J.L. Lung Cancer Patients Have the Highest Malignancy-Associated Suicide Rate in USA: A Population Based Analysis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, F.; Feng, X.; Kaaya, R.E.; Lyu, J. Incidence of and Sociological Risk Factors for Suicide Death in Patients with Leukemia: A Population-Based Study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060520922463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, P.; Lin, X.; Zhao, Q.; Wen, X.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Incidence, Trend and Risk Factors Associated with Suicide among Patients with Malignant Intracranial Tumors: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 27, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendal, W.S.; Kendal, W.M. Comparative Risk Factors for Accidental and Suicidal Death in Cancer Patients. Crisis 2012, 33, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Cai, K.; Huang, Y.; Lyu, J. Risk Factors Associated with Suicide among Leukemia Patients: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9006–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wu, W.; Fu, R.; Zheng, S.; Bai, R.; Lyu, J. Coincident Patterns of Suicide Risk among Adult Patients with a Primary Solid Tumor: A Large-Scale Population Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, F.; Cai, Q.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Lin, H. Risk Factors Associated with Suicide among Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Shi, H.-Y.; Qian, Y.; Jin, X.-H.; Yu, H.-R.; Fu, X.-L.; Song, Y.-P.; Chen, H.-L.; Shi, Y.-Q. Insurance Status and Risk of Suicide Mortality among Patients with Cancer: A Retrospective Study Based on the SEER Database. Public Health 2021, 194, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Qiu, Y.; Tao, J. Suicide and Cardiovascular Death among Patients with Multiple Primary Cancers in the United States. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 857194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, O. Socioeconomic Predictors of Suicide Risk among Cancer Patients in the United States: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019, 63, 101601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetto, S.S.; Sakinofsky, I. The Gender Paradox in Suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1998, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mościcki, E.K. Gender Differences in Completed and Attempted Suicides. Ann. Epidemiol. 1994, 4, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, D.J.; Benjamins, M.R.; Saiyed, N.S.; Silva, A.; Shrestha, S. Suicide Rates and Differences in Rates Between Non-Hispanic Black and Non-Hispanic White Populations in the 30 Largest US Cities, 2008–2017. Public Health Rep. 2022, 137, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neeleman, J.; Wessely, S.; Lewis, G. Suicide Acceptability in African- and White Americans: The Role of Religion. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1998, 186, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockett, I.R.H.; Samora, J.B.; Coben, J.H. The Black–White Suicide Paradox: Possible Effects of Misclassification. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, I.R.; Wang, S.; Stack, S.; De Leo, D.; Frost, J.L.; Ducatman, A.M.; Walker, R.L.; Kapusta, N.D. Race/Ethnicity and Potential Suicide Misclassification: Window on a Minority Suicide Paradox? BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchand, R.; Gordon, J.A.; Pearson, J.L. Trends in Suicide Rates by Race and Ethnicity in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messias, E.; Salas, J.; Wilson, L.; Scherrer, J.F. Temporal Location of Changes in the US Suicide Rate by Age, Ethnicity, and Race: A Joinpoint Analysis 1999–2020. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2023, 211, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D. Late-Life Suicide in an Aging World. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fang, W.; Liu, J.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hong, S.; Huang, Y.; et al. Suicide among Cancer Patients: Adolescents and Young Adult (AYA) versus All-Age Patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, E.O.; Mehlum, L.; Qin, P. Marital Status and Suicide Risk: Temporal Effect of Marital Breakdown and Contextual Difference by Socioeconomic Status. SSM—Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denney, J.T.; Rogers, R.G.; Krueger, P.M.; Wadsworth, T. Adult Suicide Mortality in the United States: Marital Status, Family Size, Socioeconomic Status, and Differences by Sex. Soc. Social. Sci. Q. 2009, 90, 1167–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kposowa, A.J. Marital Status and Suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øien-Ødegaard, C.; Hauge, L.J.; Reneflot, A. Marital Status, Educational Attainment, and Suicide Risk: A Norwegian Register-Based Population Study. Popul. Health Metr. 2021, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, R.; Rehm, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Gozdyra, P.; Kurdyak, P. Rurality and Risk of Suicide Attempts and Death by Suicide among People Living in Four English-Speaking High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searles, V.B.; Valley, M.A.; Hedegaard, H.; Betz, M.E. Suicides in Urban and Rural Counties in the United States, 2006–2008. Crisis 2014, 35, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-U.; Oh, I.-H.; Jeon, H.J.; Roh, S. Suicide Rates across Income Levels: Retrospective Cohort Data on 1 Million Participants Collected between 2003 and 2013 in South Korea. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Morin, S.B.; Bourand, N.M.; DeClue, I.L.; Delgado, G.E.; Fan, J.; Foster, S.K.; Imam, M.S.; Johnston, C.B.; Joseph, F.B.; et al. Social Vulnerability and Risk of Suicide in US Adults, 2016-2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e239995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.V.; Garlow, S.J.; Brawley, O.W.; Master, V.A. Peak Window of Suicides Occurs within the First Month of Diagnosis: Implications for Clinical Oncology. Psychooncology 2012, 21, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Kong, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Ren, Y.; Dong, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J. Subsequent Risk of Suicide among 9,300,812 Cancer Survivors in US: A Population-Based Cohort Study Covering 40 Years of Data. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahara, K.; Farooq, S.A.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Merath, K.; Paredes, A.Z.; Wu, L.; Mehta, R.; Hyer, J.M.; Endo, I.; Pawlik, T.M. Immunotherapy Utilization for Hepatobiliary Cancer in the United States: Disparities among Patients with Different Socioeconomic Status. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2020, 9, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyers, J.T.; Patel, A.; Shih, W.; Nagaraj, G. Association of Sociodemographic Factors with Immunotherapy Receipt for Metastatic Melanoma in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2015656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.C.; Lauzon, M.; Luu, M.; Noureddin, M.; Ayoub, W.; Kuo, A.; Sundaram, V.; Kosari, K.; Nissen, N.; Gong, J.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Early Treatment with Immunotherapy for Advanced HCC in the United States. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, K.R.; Szymanski, B.R.; Kelley, M.J.; Katz, I.R.; McCarthy, J.F. Suicide Risk Following a New Cancer Diagnosis among Veterans in Veterans Health Administration Care. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 3520–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, K.E.; Brock, R.; Charnock, J.; Wickramasinghe, B.; Will, O.; Pitman, A. Risk of Suicide after Cancer Diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseri, K.; Mills, P.K.; Mirshahidi, H.R.; Moulton, L.H. Suicide in Cancer Patients in California, 1997–2006. Arch. Suicide Res. 2012, 16, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komic, A.; Taludker, A.; Walsh, N.; Jones, A.; Lawson, A.; Bateson, B.; Kruse, E.J. Suicide Risk in Melanoma: What Do We Know? Am. Surg. 2017, 83, E435–E437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M.; Marti, C.N.; Conwell, Y. Physical Health Problems as a Late-Life Suicide Precipitant: Examination of Coroner/Medical Examiner and Law Enforcement Reports. Gerontol. 2019, 59, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivarov, V.; Shivarov, H.; Yordanov, A. Seasonality of Suicides among Cancer Patients. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2022, 53, 1932–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.J.; Travis, L.B.; Chen, M.-H.; Arvold, N.D.; Nguyen, P.L.; Martin, N.E.; Kuban, D.A.; Ng, A.K.; Hoffman, K.E. Outcomes in Stage I Testicular Seminoma: A Population-Based Study of 9193 Patients: Mortality in Stage 1 Testicular Seminoma. Cancer 2013, 119, 2771–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboumrad, M.; Fuld, A.; Soncrant, C.; Neily, J.; Paull, D.; Watts, B.V. Root Cause Analysis of Oncology Adverse Events in the Veterans Health Administration. J. Oncol. Pr. Pract. 2018, 14, e579–e590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Nan, J.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, H. Cause of Death among Patients with Thyroid Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 852347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanee, S.; Russo, P. Suicide in Men with Testis Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, K.K.; Malafa, M.P.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Schell, M.J.; Sarr, M.G. Suicide in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Qu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Lu, D.; Song, H. Increased Risk of Suicide among Cancer Survivors Who Developed a Second Malignant Neoplasm. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2066133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, F.; Keating, N.L.; Mucci, L.A.; Adami, H.-O.; Stampfer, M.J.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.; Fall, K. Immediate Risk of Suicide and Cardiovascular Death after a Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Cohort Study in the United States. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.M.; Gad, M.M.; Al-Husseini, M.J.; AlKhayat, M.A.; Rachid, A.; Alfaar, A.S.; Hamoda, H.M. Suicidal Death within a Year of a Cancer Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. Cancer 2019, 125, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracuse, B.L.; Gorgy, G.; Ruskin, J.; Beebe, K.S. What Is the Incidence of Suicide in Patients with Bone and Soft Tissue Cancer?: Suicide and Sarcoma. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.R.; Mackley, H.; Snyder, T.; Lehrer, E.J.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Zaorsky, N.G. Long-Term Causes of Death among Pediatric Cancer Patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, E16–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhu, M.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Bian, X.; Yang, L.; Jiang, X.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Suicide Death among Kaposi’s Sarcoma Patients: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e920711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.M.; Johnson, K.J.; Grove, J.L.; Srivastava, A.J.; Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Perkins, S.M. Risk of Suicide among Individuals with a History of Childhood Cancer. Cancer 2022, 128, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, W.; Yu, S.; Ding, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tang, Q.; Lu, C. Risk Factors Associated with Suicide among Kidney Cancer Patients: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 5386–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Dong, X.; Mao, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.; Ma, W.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; et al. Causes of Death after Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8145173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Park, E.M.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Nichols, H.B. Suicide Rates among Patients with Cancers of the Digestive System. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2274–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; He, G.; Chen, S.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Lyu, J. Incidence and Risk Factors for Suicide Death in Male Patients with Genital-System Cancer in the United States. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, K.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Dai, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, S. Suicide and Accidental Death among Women with Primary Ovarian Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 833965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samawi, H.H.; Shaheen, A.A.; Tang, P.A.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Cheung, W.Y.; Vickers, M.M. Risk and Predictors of Suicide in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, e513–e517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, S.; Peng, P.; Ma, F.; Tang, F. Prediction of Risk of Suicide Death among Lung Cancer Patients after the Cancer Diagnosis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y.; Kang, H.; Song, K.; Dong, Y.; Peng, R.; Li, F. Suicide and Accidental Deaths among Patients with Primary Malignant Bone Tumors. J. Bone Oncol. 2021, 27, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osazuwa-Peters, N.; Barnes, J.M.; Okafor, S.I.; Taylor, D.B.; Hussaini, A.S.; Adjei Boakye, E.; Simpson, M.C.; Graboyes, E.M.; Lee, W.T. Incidence and Risk of Suicide among Patients with Head and Neck Cancer in Rural, Urban, and Metropolitan Areas. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 147, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalela, D.; Krishna, N.; Okwara, J.; Preston, M.A.; Abdollah, F.; Choueiri, T.K.; Reznor, G.; Sammon, J.D.; Schmid, M.; Kibel, A.S.; et al. Suicide and Accidental Deaths among Patients with Non-Metastatic Prostate Cancer. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakrishnan, T.T.; Sekigami, Y.; Rajeev, R.; Gamblin, T.C.; Turaga, K.K. Morbidity of Curative Cancer Surgery and Suicide Risk. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heynemann, S.; Thompson, K.; Moncur, D.; Silva, S.; Jayawardana, M.; Lewin, J. Risk Factors Associated with Suicide in Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) with Cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 7339–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Hou, X. Incidence of Suicide among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Talukder, A.M.; Walsh, N.J.; Lawson, A.G.; Jones, A.J.; Bishop, J.L.; Kruse, E.J. Clinical and Epidemiological Factors Associated with Suicide in Colorectal Cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.-L.; Wu, H.; Qian, Y.; Jin, X.-H.; Yu, H.-R.; Du, L.; Chen, H.-L.; Shi, Y.-Q. Incidence of Suicide Mortality among Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Population-Based Retrospective Study. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 304, 114119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.G.; Klaassen, Z.; Jen, R.P.; Hughes, W.M.; Neal, D.E., Jr.; Terris, M.K. Analysis of Suicide Risk in Patients with Penile Cancer and Review of the Literature. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2018, 16, e257–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Churilla, T.M.; Egleston, B.L.; Fisher, S.G.; Ridge, J.A.; Horwitz, E.M.; Meyer, J.E. Causes of Death among Cancer Patients. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Studies included | 73 | 100 |

| PubMed indexed | 71 | 97 |

| Database used SEER | 69 | 95 |

| Other | 5 | 7 |

| Comparison group | ||

| US general population | 47 | 64 |

| Other | 14 | 19 |

| Study design | ||

| Cross-sectional | 70 | 96 |

| Longitudinal data | 53 | 73 |

| Longitudinal trends | 3 | 4 |

| Regions included | ||

| Full US | 72 | 99 |

| California | 1 | 1 |

| Covariates analyzed Sex | 60 | 82 |

| Age | 58 | 79 |

| Race | 69 | 95 |

| Time | 51 | 70 |

| Geography | 18 | 25 |

| Socioeconomic status | 20 | 27 |

| Cancer types analyzed | ||

| All | 20 | 27 |

| Genitourinary | 13 | 18 |

| Head and neck | 9 | 12 |

| Gastrointestinal | 5 | 7 |

| Lung and bronchus | 3 | 4 |

| Breast | 3 | 4 |

| Gynecological | 3 | 4 |

| All solid | 2 | 3 |

| Hematologic | 2 | 3 |

| Brain | 2 | 3 |

| Pancreas | 2 | 3 |

| Bone and soft tissue | 2 | 3 |

| Skin | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 3 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grobman, B.; Mansur, A.; Babalola, D.; Srinivasan, A.P.; Antonio, J.M.; Lu, C.Y. Suicide among Cancer Patients: Current Knowledge and Directions for Observational Research. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206563

Grobman B, Mansur A, Babalola D, Srinivasan AP, Antonio JM, Lu CY. Suicide among Cancer Patients: Current Knowledge and Directions for Observational Research. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(20):6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206563

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrobman, Ben, Arian Mansur, Dolapo Babalola, Anirudh P. Srinivasan, Jose Marco Antonio, and Christine Y. Lu. 2023. "Suicide among Cancer Patients: Current Knowledge and Directions for Observational Research" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 20: 6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206563

APA StyleGrobman, B., Mansur, A., Babalola, D., Srinivasan, A. P., Antonio, J. M., & Lu, C. Y. (2023). Suicide among Cancer Patients: Current Knowledge and Directions for Observational Research. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(20), 6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206563