Testicular Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

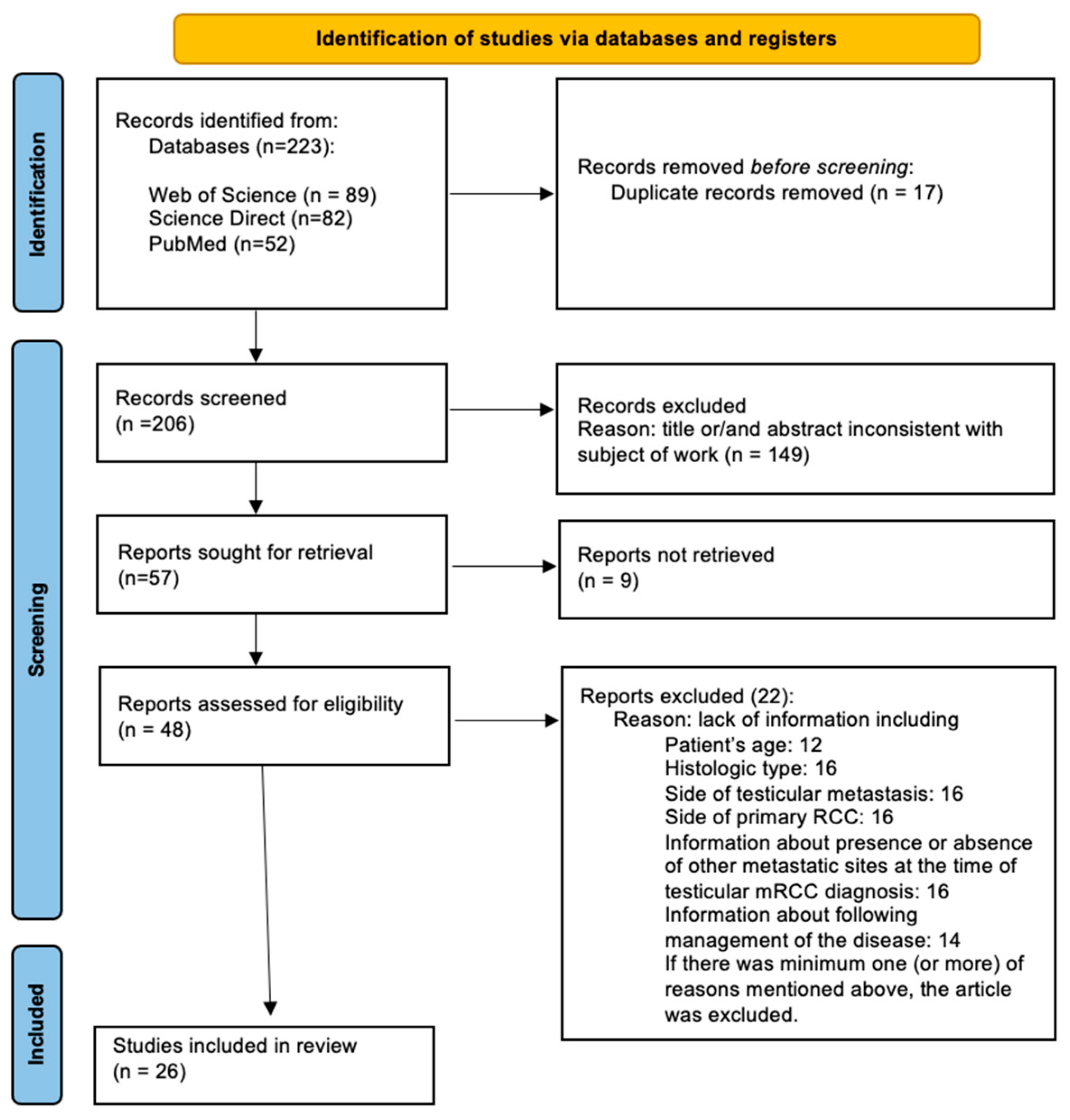

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Assessment

- -

- Review articles and conference abstracts and studies void of any original data.

- -

- Works that provided incomplete or non-extractable data (such as lack of patient age (12), histological type (16), side of testicular metastasis (16), and side of primary RCC (16); information about the presence or absence of other metastatic sites at the time of diagnosis of testicular mRCC (16), information about follow-up management of the disease (14) or one impossible to extract.

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Study Endpoints

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Methodology

2.6.2. Statistical Environment

3. Results

3.1. Study Identification

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Study Identification

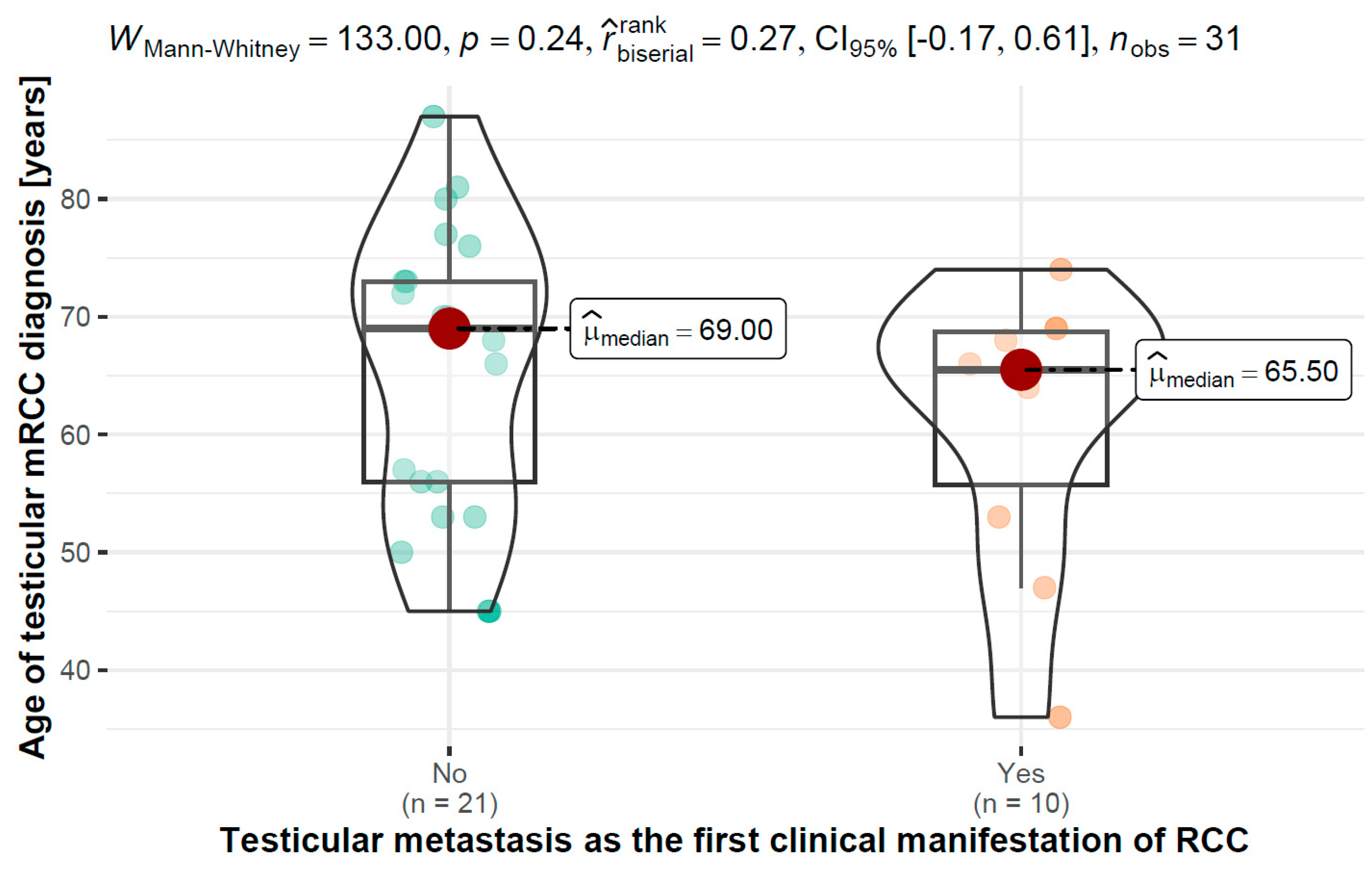

3.4. Age of Testicular Diagnosis of mRCC vs. Testicular Metastasis as the First Clinical Manifestation of RCC

3.5. Age of Testicular mRCC Diagnosis vs.Time Period between Primary Kidney Tumor Diagnosis and Testicular Metastasis

3.6. Testicular mRCC Side in Relation to Kidney Primary RCC Side

3.7. T Stage of Primary RCC vs. Testicular Metastasis as the First Clinical Manifestation of RCC

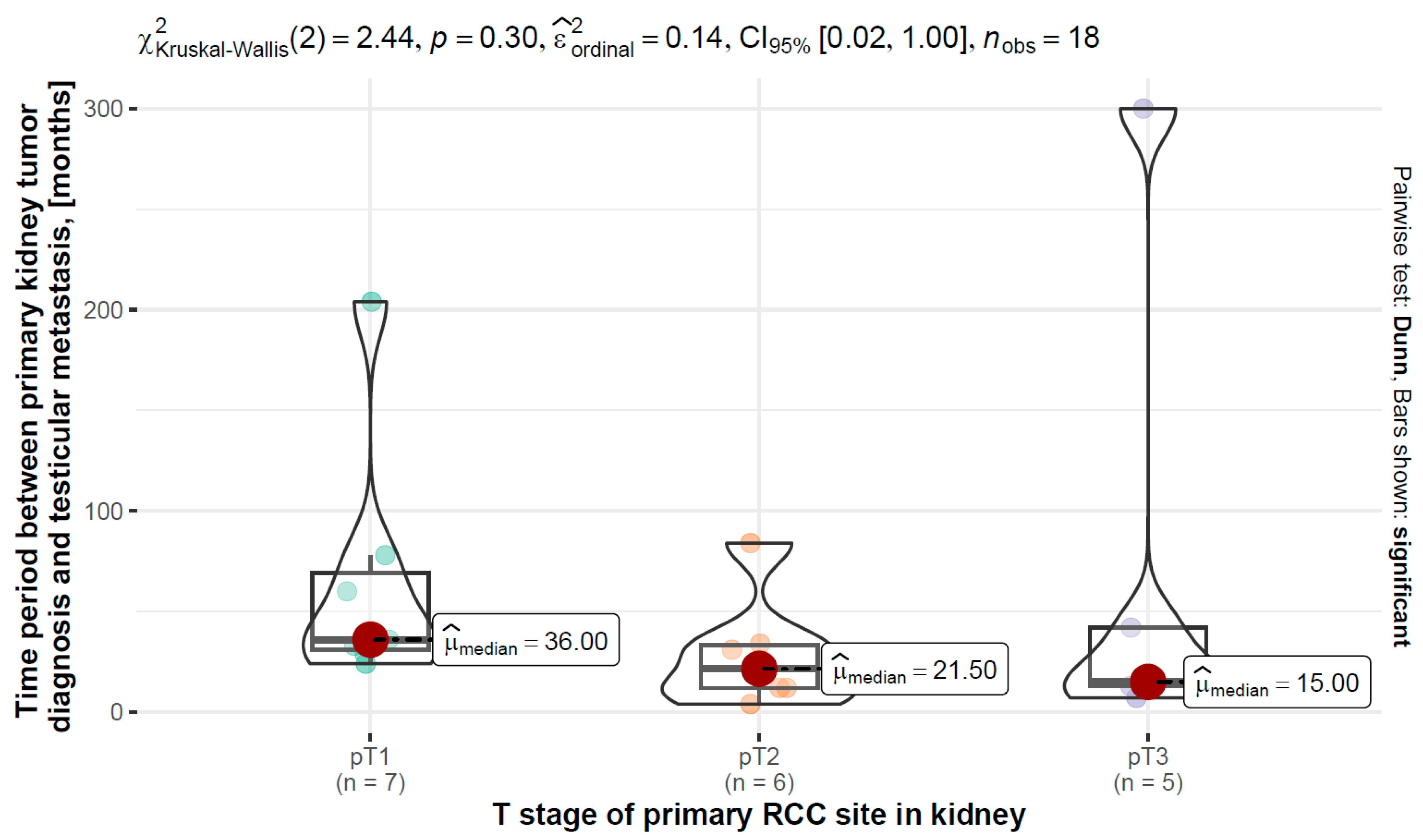

3.8. T Stage of Primary RCC vs. Time Period between Primary Kidney Tumor Diagnosis and Testicular Metastasis

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capitanio, U.; Bensalah, K.; Bex, A.; Boorjian, S.A.; Bray, F.; Coleman, J.; Gore, J.L.; Sun, M.; Wood, C.; Russo, P. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, K.; Alyami, F.; Merrimen, J.; Bagnell, S. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the testis: A case report and review of the literature. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014, 8, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Mostafaei, H.; Miura, N.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Luzzago, S.; Schmidinger, M.; Bruchbacher, A.; Pradere, B.; Egawa, S.; Shariat, S.F. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the first-line setting: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, D.M.; Hahn, A.W.; Hale, P.; Maughan, B.L. Overview of Current and Future First-Line Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, E.M.; Limvorasak, S.; Figlin, R.A. Targeted therapies for renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishna, B.; Gupta, N.P.; Wadhwa, P.; Hemal, A.K.; Dogra, P.N.; Seth, A.; Aron, M.; Kumar, R. Pattern of metastases in renal cell carcinoma: A single institution study. Indian J. Cancer 2005, 42, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bandler, C.G.; Roen, P.R. Solitary Testicular Metastasis Simulating Primary Tumor and Antedating Clinical Hypernephroma of the Kidney: Report of a Case. J. Urol. 1946, 55, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhou, C.; Villamil, C.F.; So, A.; Yuan, R.; English, J.C.; Jones, E.C. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Testis: A Clinicopathologic Analysis of Five Cases. Case Rep. Pathol. 2020, 2020, 9394680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; McKenzie, J.E. Introduction to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetic, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, H.M.; Mann, R.B.; Trump, D.L.; Abeloff, M.D. Metastatic carcinoma involving the testis. Clinical and pathologic distinction from primary testicular neoplasms. Cancer 1984, 54, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, K.-P.; Düe, W.; Loy, V. Intrascrotal Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 1988, 15, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, G.F.; Schaeffer, A.J. Renal cell carcinoma involving penis and testis: Unusual initial presentations of metastatic disease. Urology 1991, 37, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, D.H.G. Simultaneous Contralateral Testicular Metastasis from a Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 1999, 33, 136–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, A.; Tartarelli, G.; Martini, L.; Donati, S.; Puccinelli, P.; Amoroso, D. Ipsilateral right testicular metastasis from renal cell carcinoma in a responder patient to interleukine-2 treatment. Int. J. Urol. 2007, 14, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemoto, K.; Shimizu, H.; Kimura, G. Testicular metastasis and local recurrence of renal cell carcinoma after nephron-sparing surgery in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urol. Jpn. 2007, 53, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Schmorl, P.; Ostertag, H.; Conrad, S. Intratestikuläre Metastasierung eines Nierenzellkarzinoms [Intratesticular metastasis of renal cancer]. Die Urol. 2008, 47, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llarena Ibarguren, R.; García-Olaverri Rodríguez, J.; Azurmendi Arin, I.; Olano Grasa, I.; Pertusa Peña, C. Metástasis testicular metacrónica secundaria a adenocarcinoma renal de células claras [Metachronic testicular metastasis secondary to clear cell renal adenocarcinoma]. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2008, 61, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, H.-Y.; Xu, L.-W.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Yu, Y.-L.; Li, X.-D.; Li, G.-H. Metachronous contralateral testicular and bilateral adrenal metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2010, 11, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, S.; Takeshita, H.; Adachi, A.; Arai, Y.; Higuchi, S.; Tokairin, T.; Chiba, K.; Nakagawa, K.; Noro, A. Simultaneous bilateral testicular metastases from renal clear cell carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Atti, L. Unusual Ultrasound Presentation of Testicular Metastasis from Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma. Rare Tumors 2016, 8, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongnyuy, M.; Lawindy, S.; Martinez, D.; Parker, J.; Hall, M. A Rare Case of the Simultaneous, Multifocal, Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Ipsilateral Left Testes, Bladder, and Stomach. Case Rep. Urol. 2016, 2016, 1829025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libert, F.; Cabri-Wiltzer, M.; Dardenne, E.; Draguet, A.-P.; Puttemans, T. Ultrasonographic Pattern of Testicular Metastasis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma with Pathological Correlation. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2016, 100, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, R.; Tulchiner, G.; Aigner, F.; Horninger, W.; Heidegger, I. Paratesticular Metastasis of a Clear-Cell Renal-Cell Carcinoma With Renal Vein Thrombus Mimicking Primary Testicular Cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 15, e123–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvinov, K.; Neulander, E.Z.; Kan, E.; Asali, M.; Ariad, S.; Mermershtain, W. Testicular Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Oncol. 2017, 10, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ling, W.; Qiu, T.; Luo, Y. Ultrasonographic features of testicular metastasis from renal clear cell carcinoma that mimics a seminoma: A case report. Medicine 2018, 97, e12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolukcu, E.; Kilic, S.; Parlaktas, B.S.; Deresoy, F.A.; Atilgan, D.; Gumusay, O.; Uluocak, N. Contralateral Testicular Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report. Eurasian J. Med. 2019, 51, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gobbi, A.; Mangano, M.S.; Cova, G.; Lamon, C.; Maccatrozzo, L. Testicular metastasis from renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy and on tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy: Case report and review. Urol. J. 2019, 86, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, L.; Pahernik, S.; Pandey, A. Harnleiter und Hodenmetastase 25 Jahre nach Nephrektomie: Langjähriges Überleben mit einem metastasierten Nierenzellkarzinom [Ureteric and testicular mestastasis 25 years after nephrectomy: Long-term survival with metastatic renal cell carcinoma]. Der Urologe Ausg. 2020, 59, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safriadi, F.; Noegroho, B.S.; Partogu, B. Papillary renal cell carcinoma with testicular and penile metastases: A case report and literature review. Urol. Case Rep. 2020, 33, 101362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turco, F.; Tucci, M.; Di Stefano, R.F.; Samuelly, A.; Bungaro, M.; Bollito, E.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Buttigliero, C. Are tyrosine kinase inhibitors an effective treatment in testicular metastases from kidney cancer? Case report. Tumori J. 2021, 107, NP149–NP154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Farhoumand, D.; Bouzari, B.; Shakiba, B. Simultaneous Bilateral Testicular Metastases from Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma: A Rare Presentation in Von Hippel–Lindau disease. J. Kidney Cancer VHL 2022, 9, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balawender, K.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Pliszka, A.; Rajda, S.; Walocha, J.; Wysiadecki, G. Can renal cell carcinoma be encountered in male gonads? A rare primary manifestation of advanced kidney cancer? Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.; Park, E.M.; du Plessis, J.; Rachakonda, K.; Liodakis, P. Rare presentation of a clear cell renal cell cancer metastasis to the contralateral testicle: A case report. Urol. Case Rep. 2023, 46, 102299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, R.C.; Campbell, S.C.; Clark, J.I.; Picken, M.M. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2003, 4, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.; Rini, B.; Garcia, J.; Baz, R.; Abou-Jawde, R.; Thakkar, S.; Elson, P.; Mekhail, T.; Zhou, M.; Bukowski, R. Prognostic factors associated with long-term survival in previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudani, S.; de Velasco, G.; Wells, C.; Gan, C.L.; Donskov, F.; Porta, C.; Fraccon, A.; Pasini, F.; Hansen, A.R.; Bjarnason, G.A.; et al. Sites of metastasis and survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Results from the International mRCC Database Consortium (IMDC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, S.; Oya, M.; Mizuno, R.; Kosaka, T.; Katsube, K.-I.; Okada, Y. Invasion and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2014, 47, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, G.; Cella, D.; Robinson, D.; Mahadevia, P.J.; Clark, J.; Revicki, D.A. Symptom burden among patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Content for a symptom index. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazarian, A.A.; Rusner, C.; Trabert, B.; Braunlin, M.; McGlynn, K.A.; Stang, A. Testicular cancer among US men aged 50 years and older. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 55, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Daneshmand, S. Modern Management of Testicular Cancer. In Genitourinary Cancers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 175, pp. 273–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAU Guidelines Office. EAU Guidelines. Edn. Presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 29–62. ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R.E.; Harris, G.T. Carcinoma: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 99, 179–184, Erratum in Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 99, 732. [Google Scholar]

| Case No. | References | Were Patients’ Demographic Characteristics Clearly Described? | Was the Patient’s History Clearly Described and Presented as a Timeline? | Was the Current Clinical Condition of the Patient on Presentation Clearly Described? | Were Diagnostic Tests or Assessment Methods and the Results Clearly Described? | Was the Intervention(s) or Treatment Procedure(s) Clearly Described? | Was the Post-Intervention Clinical Condition Clearly Described? | Were Adverse Events (Harms) or Unanticipated Events Identified and Described? | Does the Case Report Provide Takeaway Lessons? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bandler and Roen, 1946 [7] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2. | Haupt et al., 1984 [11] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. | Dieckmann, Due and Loy, 1988 [12] | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. | Daniels and Schaefer, 1991 [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 5. | Steiner et al., 1999 [14] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 6. | Camerini et al., 2007 [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7. | Nemoto, Shimizu, and Kimura, 2007 [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| 8. | Schmorl, Ostertag and Conrad, 2008 [17] | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 9. | Llarena et al., 2008 [18] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| 10. | Wu et al., 2010 [19] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 11. | Moriyama et al., 2014 [20] | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes |

| 12. | Dell’Atti, 2016 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 13. | Kongnyuy et al., 2016 [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes |

| 14. | Libert et al., 2016 [23] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 15. | Libert et al., 2016 [23] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 16. | Pichler et al., 2017 [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 17. | Rouvinov et al., 2017 [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes |

| 18. | Huang et al., 2018 [26] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 19. | Kolukcu et al., 2019 [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 20. | De Gobbi et al., 2019 [28] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 21. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 22. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 23. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | No | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

| 24. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | Yes |

| 25. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | No | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| 26. | De Jonge, Pahernik and Pandey, 2020 [29] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 27. | Safriadi, Noegroho and Partogu, 2020 [30] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 28. | Turco et al., 2021 [31] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| 29. | Moradi et al, 2022 [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 30. | Balawender et al., 2023 [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| 31. | Thomson et al., 2023 [34] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Case No. | References | Age of Testicular mRCC Diagnosis [Years] | Histopathological Type | “T” Stage of Primary RCC Site in Kidney | Grading in the Fuhrman Scale | Side | Testicular mRCC Side in Relation to Kidney Primary RCC Side | Other Metastatic Sites Present at the Time of Testicular mRCC Diagnosis | Testicular Metastasis as the First Clinical Manifestation of RCC | Time Period between Primary Kidney Tumor Diagnosis and Testicular Metastasis [months] | Primary Kidney Tumor Treatment | Metastasis Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bandler and Roen, 1946 [7] | 47 | unclassified | N/A | N/A | right | ipsilateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | Yes | N/A | radical right nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 2. | Haupt et al., 1984 [11] | 36 | unclassified | N/A | N/A | left | ipsilateral | inguinal lymph nodes | Yes | N/A | chemotherapy (Adriamycin, 5-fluorouracil, vincristine, mitomycin C) with radiotherapy | left orchiectomy |

| 3. | Dieckmann, Due and Loy, 1988 [12] | 73 | clear cell | pT3a | N/A | left | ipsilateral | lungs | No | 13 | tumor vessels embolization as palliative treatment | left orchiectomy |

| 4. | Daniels and Schaefer, 1991 [13] | 87 | clear cell | pT3 | N/A | right | contralateral | paraaortic, paravertebral lymph nodes | No | 15 | left radical nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 5. | Steiner et al., 1999 [14] | 66 | clear cell | pT1b | N/A | left | contralateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | Yes | N/A | right radical nephrectomy | left orchiectomy |

| 6. | Camerini et al., 2007 [15] | 45 | clear cell | pT2 | G2 | right | ipsilateral | bones, lungs, pleura | No | 4 | right radical nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 7. | Nemoto, Shimizu, and Kimura, 2007 [16] | 56 | clear cell | pT1b | G1 | left | ipsilateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 36 | left nephron-sparing surgery followed by left radical nephrectomy | left orchiectomy |

| 8. | Schmorl, Ostertag and Conrad, 2008 [17] | 66 | clear cell | pT3a | G2 | right | ipsilateral | bones | No | 42 | radical right nephrectomy | immunochemotheraphy (Interferone, Interleukine-2, 5-Fluorouracil) |

| 9. | Llarena et al., 2008 [18] | 57 | clear cell | pT2 | G2 | right | ipsilateral | bones | No | 12 | right radical nephrectomy | immunochemotheraphy (IL-2 inhalations changed for Sorafenib), right orchiectomy |

| 10. | Wu, Hai-Yang et al., 2010 [19] | 70 | chromophobe renal cell | N/A | N/A | left | contralateral | adrenal glands | No | 72 | right radical nephrectomy | bilateral adrenalectomy, left orchiectomy |

| 11. | Moriyama et al., 2014 [20] | 65 | clear cell | pT1b | N/A | bilateral | N/A | pancreas, adrenal glands | Yes | N/A | left nephron-sparing surgery, followed by left radical nephrectomy | bilateral orchiectomy |

| 12. | Dell’Atti, 2016 [21] | 69 | clear cell | pT1b | N/A | left | ipsilateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 24 | left radical nephrectomy | left orchiectomy |

| 13. | Kongnyuy et al., 2016 [22] | 68 | clear cell | pT3a | G4 | left | contralateral | lungs | Yes | N/A | right radical nephrectomy followed by sunatinib, changed for atixitinib | left orchiectomy |

| 14. | Libert et al., 2016 [23] | 69 | clear cell | pT1b | N/A | right | ipsilateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | Yes | N/A | right radical nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 15. | Libert et al., 2016 [23] | 77 | clear cell | N/A | N/A | left | ipsilateral | lungs | No | 60 | left nephron-sparing surgery | left orchiectomy |

| 16. | Pichler et al., 2017 [24] | 53 | clear cell | pT3b | G3 | left | ipsilateral | lungs, liver | Yes (paratesticular metastases with spermatic cord infiltration) | N/A | radical nephrectomy with cavotomy and thrombectomy | chemotherapy (Sunitinib), left orchiectomy |

| 17. | Rouvinov et al., 2017 [25] | 72 | clear cell | pT1b | N/A | right | ipsilateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 78 | right nephron-sparing surgery | right orchiectomy |

| 18. | Huang et al., 2018 [26] | 64 | clear cell | pT3a | G2 | right | ipsilateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | Yes | N/A | right radical nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 19. | Kolucu et al., 2019 [27] | 56 | clear cell | pT2a | G2 | left | contralateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 12 | right radical nephrectomy | chemotherapy (Sunitinib), right orchiectomy |

| 20. | De Gobbi et al., 2019 [28] | 53 | clear cell | pT3a | G3 | left | ipsilateral | lungs | No | 7 | left radical nephrectomy with thrombectomy | chemotherapy (Sunitinib, changed for programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors: anti-PD-1 + Nivolumab), left orchiectomy |

| 21. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | 53 | clear cell | pT1 | G1 | bilateral | N/A | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 33 | tumor vessels embolization followed by left nephron sparing surgery | bilateral orchiectomy |

| 22. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | 81 | clear cell | pT2a | G3 | left | ipsilateral | bones | No | 34 | left radical nephrectomy | left orchiectomy |

| 23. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | 45 | clear cell | pT2b | G4 | right | contralateral | bones | No | 31 | left radical nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 24. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | 76 | clear cell | pT1 | G1 | right | contralateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 29 | left nephron-sparing surgery followed by left radical nephrectomy | right orchiectomy |

| 25. | Gang Wang et al., 2020 [8] | 68 | clear cell | pT2b | N/A | left | ipsilateral | bladder, stomach | No | 84 | left radical nephrectomy | left orchiectiomy, gastric polyp resection, TURBT |

| 26. | De Jonge, Pahernik and Pandey, 2020 [29] | 70 | clear cell | pT3a | N/A | right | N/A | lungs, thyroid, brain | No | 300 | right nephrectomy, left nephron sparing surgery | chemotherapy (Interferon/Interleukin, Sunitinib, Nivolumab, experimental arm of the phase III GOLD study: sorafenib vs. Dovitinib), pulmonary metastasectomy, stereotactic radiation, right orchiectomy |

| 27. | Safriadi, Noegroho and Partogu, 2020 [30] | 69 | papillary | pT2b | N/A | left | ipsilateral | penis, liver | Yes | N/A | left nephrectomy | chemotherapy (Lenvatinib), left orchiectomy, penectomy |

| 28. | Turco et al., 2021 [31] | 73 | clear cell | pT1a | G1 | right | ipsilateral | lungs, liver, pancreas | No | 204 | right nephron-sparing surgery | chemotherapy (Sunitinib changed for Cabozantinib, then for Nivolumab), left orchiectomy |

| 29. | Moradi et al, 2022 [32] | 50 | clear cell | pT1b | G3 | bilateral | N/A | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | No information provided | left nephrectomy | chemotherapy (Sunitinib), bilateral orchiectomy |

| 30. | Balawender et al., 2023 [33] | 74 | clear cell | pT4 | G3 | left | N/A | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | Yes | N/A | N/A (qualified to tki therapy but died before treatment) | Left orchiectomy |

| 31. | Thomson et al., 2023 [34] | 80 | clear cell | pT1a | G2 | left | contralateral | no other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis | No | 60 | right nephrectomy | Left orchiectomy |

| Parameter | N | Mdn (Q1–Q3) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of diagnosis of testicular mRCC, [years] | 31 | 68.0 (54.5–72.5) |

| Time period between primary kidney tumor diagnosis and testicular metastasis [months] | 20 | 33.5 (14.5–63.0) |

| N | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Histopathological type: | ||

| 31 | 27 (87.2) 1 (3.2) 1 (3.2) 2 (6.4) |

| “T” stage of the primary RCC site in the kidney: | ||

| 27 | 2 (7.4) 2 (7.4) 7 (25.9) 2 (7.4) 2 (7.4) 3 (11.1) 1 (3.7) 6 (22.3) 1 (3.7) 1 (3.7) |

| Grading in the Fuhrman scale | 17 | |

| 4 (23.5) 6 (35.3) 5 (29.4) 2 (11.8) | |

| Side: | ||

| 31 | 3 (9.7) 16 (51.6) 12 (38.7) |

| Testicular mRCC side in relation to kidney primary RCC side: | ||

| 26 | 8 (30.8) 18 (69.2) |

| Other metastatic sites present at the time of testicular mRCC diagnosis: | ||

| 31 | 13 (41.9) 5 (16.1) 8 (25.7) 10 (32.3) |

| Testicular metastasis as the first clinical manifestation of RCC: | 31 | |

| 21 (67.7) 10 (32.3) | |

| Primary kidney tumor treatment: | ||

| 31 | 24 (77.4) 2 (6.5) 8 (25.8) 2 (6.5) 4 (12.9) |

| Metastasis treatment: | ||

| 31 | 27 (87.1) 3 (9.7) 8 (25.8) 4 (12.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pliszka, A.; Rajda, S.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Walocha, J.; Polguj, M.; Wysiadecki, G.; Clarke, E.; Golberg, M.; Zarzecki, M.; Balawender, K. Testicular Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175636

Pliszka A, Rajda S, Wawrzyniak A, Walocha J, Polguj M, Wysiadecki G, Clarke E, Golberg M, Zarzecki M, Balawender K. Testicular Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(17):5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175636

Chicago/Turabian StylePliszka, Anna, Sebastian Rajda, Agata Wawrzyniak, Jerzy Walocha, Michał Polguj, Grzegorz Wysiadecki, Edward Clarke, Michał Golberg, Michał Zarzecki, and Krzysztof Balawender. 2023. "Testicular Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 17: 5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175636

APA StylePliszka, A., Rajda, S., Wawrzyniak, A., Walocha, J., Polguj, M., Wysiadecki, G., Clarke, E., Golberg, M., Zarzecki, M., & Balawender, K. (2023). Testicular Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(17), 5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175636