The Efficacy of Misoprostol Vaginal Inserts for Induction of Labor in Women with Very Unfavorable Cervices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

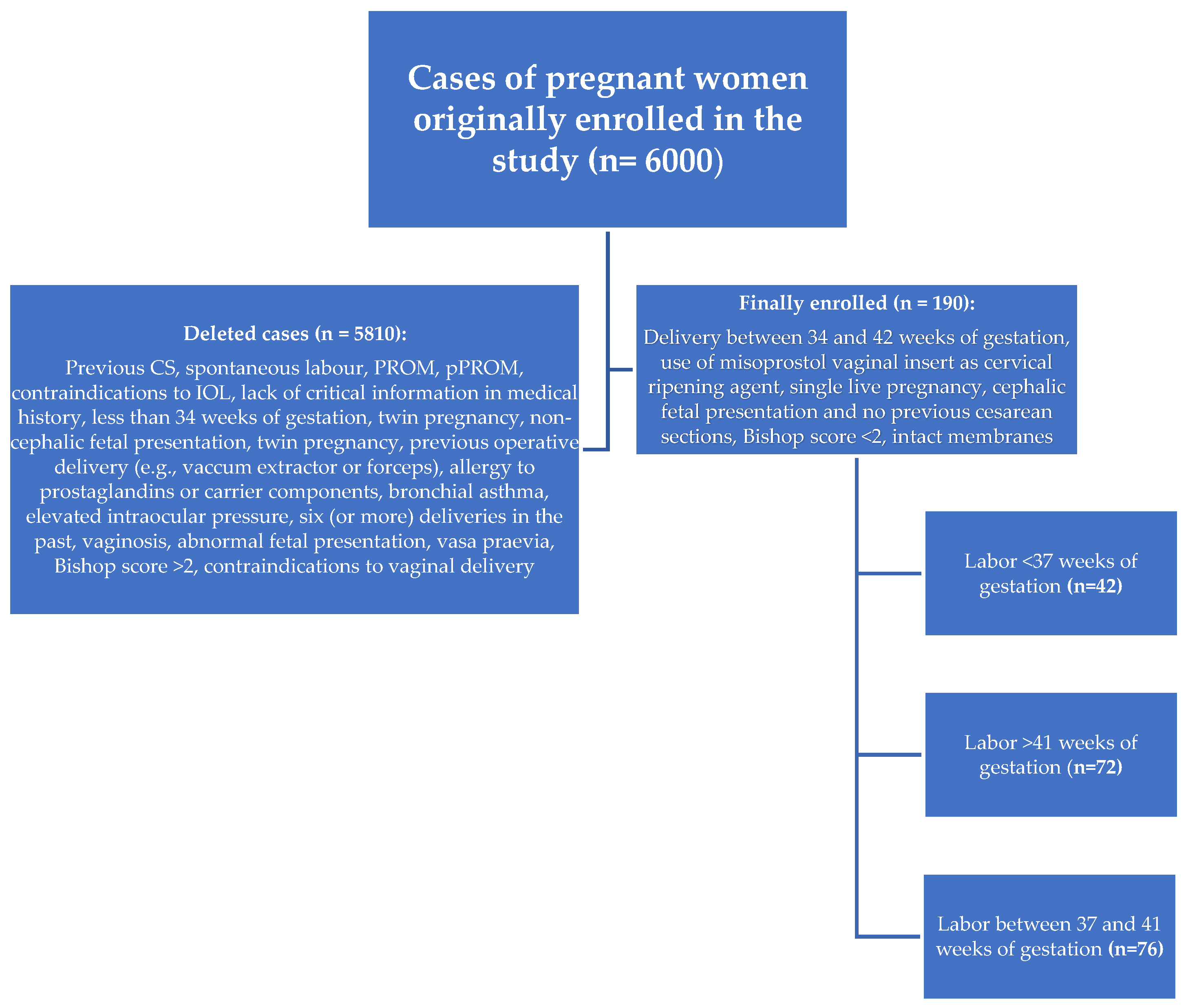

2. Materials and Methods

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The use of vaginal misoprostol in labor induction is highly effective in achieving vaginal delivery within 48 h in women with a very unfavorable cervix (Bishop < 2).

- The use of misoprostol may be associated with shortening the time to delivery (both vaginal and cesarean).

- The use of misoprostol in a group of post-term pregnancies with very unfavorable cervices significantly increased the rate of vaginal deliveries and allowed successful vaginal delivery within 24 h.

- The use of misoprostol in a post-term pregnancy group with very unfavorable cervices was associated with a lower need for oxytocin augmentation.

- Misoprostol vaginal administration for IOL may be associated with an increased desire to use analgesia during labor.

- The use of vaginal misoprostol in post-term pregnant patients with a very unfavorable cervix is associated with an increased risk of abnormal CTG recording as an indication for CS and may be associated with a lower risk of labor arrest.

- Induction of labor with misoprostol in preterm labor may require more frequent use of oxytocin augmentation.

- A misoprostol IOL regimen might be considered a safe IOL agent due to the small percentage of tachysystole cases that occurred.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicholson, J.; Kellar, L.; Henning, G.; Waheed, A.; Colon-Gonzalez, M.; Ural, S. The association between the regular use of preventive labour induction and improved term birth outcomes: Findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 122, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Keeney, E.; Dowswell, T.; Welton, N.J.; Dias, S.; Jones, L.V.; Navaratnam, K.; Caldwell, D.M. Labour induction with prostaglandins: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatsis, V.; Frey, N. Misoprostol for Cervical Ripening and Induction of Labour: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness and Guidelines; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, Y.; Narumiya, S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11613–11617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Narumiya, S.; Sugimoto, Y.; Ushikubi, F.; Alexanian, A.; Sorokin, A.; Fujii, N.; Singh, M.S.; Halili, L.; Boulay, P.; Sigal, R.J.; et al. Prostanoid Receptors: Structures, Properties, and Functions. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, R.; Pierce, S.; Myers, D. The role of prostaglandins E1 and E2, dinoprostone, and misoprostol in cervical ripening and the induction of labor: A mechanistic approach. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 296, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, S.C.; Sanchez-Ramos, L.; Adair, C.D. Labor induction with intravaginal misoprostol compared with the dinoprostone vaginal insert: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 624.e1–624.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.C.; Delaney, T.; Armson, B.A.; Fanning, C. Oral misoprostol, low dose vaginal misoprostol, and vaginal dinoprostone for labor induction: Randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzi, A.A.; Alsibiani, S.; Mansouri, N.; Alsinani, N.; Darhouse, K. Randomized clinical trial between hourly titrated oral misoprostol and vaginal dinoprostone for induction of labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 56.e1–56.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomba-Opoń, D.; Drews, K.; Huras, H.; Laudański, P.; Paszkowski, T.; Wielgoś, M. Polish Gynecological Society Recommendations for Labor Induction. Ginekol. Polska 2017, 88, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chwalisz, K.; Garfield, R.E. Role of nitric oxide in the uterus and cervix: Implications for the management of labor. J. Périnat. Med. 1998, 26, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekerhovd, E.; Brännström, M.; Weijdegård, B.; Norström, A. Nitric oxide synthases in the human cervix at term pregnancy and effects of nitric oxide on cervical smooth muscle contractility. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 183, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vaan, M.D.; Ten Eikelder, M.L.; Jozwiak, M.; Palmer, K.R.; Davies-Tuck, M.; Bloemenkamp, K.W.; Mol, B.W.J.; Boulvain, M. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD001233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierce, S.; Bakker, R.; Myers, D.A.; Edwards, R.K. Clinical insights for cervical ripening and labor induction using prostaglandins. Am. J. Perinatol. Rep. 2018, 8, e307–e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rugarn, O.; Tipping, D.; Powers, B.; Wing, D. Induction of labour with retrievable prostaglandin vaginal inserts: Outcomes following retrieval due to an intrapartum adverse event. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 124, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eikelder, M.L.G.T.; Rengerink, K.O.; Jozwiak, M.; de Leeuw, J.W.; de Graaf, I.M.; van Pampus, M.G.; Holswilder, M.; A Oudijk, M.; van Baaren, G.-J.; Pernet, P.J.M.; et al. Induction of labour at term with oral misoprostol versus a Foley catheter (PROBAAT-II): A multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, E.G.; Plachouras, N.; Drougia, A.; Andronikou, S.; Vlachou, C.; Stefos, T.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Zikopoulos, K. Comparison of Misoprostol and Dinoprostone for elective induction of labour in nulliparous women at full term: A randomized prospective study. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2004, 2, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Aflaifel, N.; Weeks, A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 13, CD001338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denguezli, W.; Trimech, A.; Haddad, A.; Hajjaji, A.; Saidani, Z.; Faleh, R.; Sakouhi, M. Efficacy and safety of six hourly vaginal misoprostol versus intracervical dinoprostone: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2007, 276, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R.S.; Kumar, N.; Williams, M.J.; Cuthbert, A.; Aflaifel, N.; Haas, D.M.; Weeks, A.D. Low-dose oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 6, CD014484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Bolnga, J.W.; Verave, O.; Aipit, J.; Rero, A.; Laman, M. Safety and effectiveness of oral misoprostol for induction of labour in a resource-limited setting: A dose escalation study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nystedt, A.; Hildingsson, I. Diverse definitions of prolonged labour and its consequences with sometimes subsequent inappropriate treatment. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, A.; Burt, R.; Rice, P.; Templeton, A. Women’s perceptions, expectations and satisfaction with induced labour—A questionnaire-based study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 123, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impey, L. Maternal attitudes to amniotomy and labor duration: A survey in early pregnancy. Birth 1999, 26, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, G.J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Pileggi, C. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, CD000941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, A.D.; Lightly, K.; Mol, B.W.; Frohlich, J.; Pontefract, S.; Williams, M.J.; the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Evaluating misoprostol and mechanical methods for induction of labour. BJOG 2022, 129, e61–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, S.J.; Ferguson, E.; Duffy, A.; Ford, I.; Chalmers, J.; Norman, J. Outcomes of elective induction of labour compared with expectant management: Population based study. BMJ 2012, 344, e2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hannah, M.E.; Hannah, W.J.; Hellmann, J.; Hewson, S.; Milner, R.; Willan, A.; the Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. Induction of Labor as Compared with Serial Antenatal Monitoring in Post-Term Pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. The Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, V.J.; Rogers, M.S. Pregnancy outcome beyond 41 weeks gestation. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1997, 59, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, C.; Mazzoni, G.; Gerosa, V.; Fratelli, N.; Prefumo, F.; Sartori, E.; Lojacono, A. Labor induction with misoprostol vaginal insert compared with dinoprostone vaginal insert. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handal-Orefice, R.C.; Friedman, A.M.; Chouinard, S.M.; Eke, A.C.; Feinberg, B.; Politch, J.; Iverson, R.E.; Yarrington, C.D. Oral or Vaginal Misoprostol for Labor Induction and Cesarean Delivery Risk. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikouras, P.; Koukouli, Z.; Manav, B.; Soilemetzidis, M.; Liberis, A.; Csorba, R.; Trypsianis, G.; Galazios, G. Induction of Labor in Post-Term Nulliparous and Parous Women—Potential Advantages of Misoprostol over Dinoprostone. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016, 76, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wing, D.A.; Brown, R.; Plante, L.A.; Miller, H.; Rugarn, O.; Powers, B.L. Misoprostol vaginal insert and time to vaginal delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redling, K.; Schaedelin, S.; Huhn, E.A.; Hoesli, I. Efficacy and safety of misoprostol vaginal insert vs. oral misoprostol for induction of labor. J. Périnat. Med. 2018, 47, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, G.A.; Fakhar, S.; Nisar, N.; Alam, A.Y. Misoprostol for term labor induction: A randomized controlled trial. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 50, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gornisiewicz, T.; Huras, H.; Kusmierska-Urban, K.; Galas, A. Pregnancy-related comorbidities and labor induction—The effectiveness and safety of dinoprostone compared to misoprostol. Ginekol. Polska 2021, 92, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ray, C.; Carayol, M.; Bréart, G.; Goffinet, F.; for the PREMODA Study Group. Elective induction of labor: Failure to follow guidelines and risk of cesarean delivery. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, T.; Devkota, R.; Bhattarai, B.; Acharya, R. Outcome of misoprostol and oxytocin in induction of labour. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5, 2050312117700809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M.L.; Powers, B.L.; Wing, D.A. Fetal heart rate and cardiotocographic abnormalities with varying dose misoprostol vaginal inserts. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013, 26, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolderup, L.; McLean, L.; Grullon, K.; Safford, K.; Kilpatrick, S.J. Misoprostol is more efficacious for labor induction than prostaglandin E2, but is it associated with more risk? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 180, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Haas, D.M.; Weeks, A.D. Misoprostol for labour induction. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 77, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorherr, H. Placental insufficiency in relation to postterm pregnancy and fetal postmaturity. Evaluation of fetoplacental function; management of the postterm gravida. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1975, 123, 67–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcioglu, O.; Topacoglu, H.; Dikme, O.; Dikme, O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blajic, I.; Zagar, T.; Semrl, N.; Umek, N.; Lucovnik, M.; Pintaric, T.S. Analgesic efficacy of remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia versus combined spinal-epidural technique in multiparous women during labour. Ginekol. Polska 2021, 92, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodzis, A.; Walędziak, M.; Czajkowski, K.; Różańska-Walędziak, A. Intrapartum Analgesia—Have Women’s Preferences Changed over the Last Decade? Medicina 2022, 58, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, I.; Fuchs, P.; Fuchs, A.; Lorek, M.; Tobolska-Lorek, D.; Drosdzol-Cop, A.; Sikora, J. Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Methods of Labour Pain Relief—Establishment of Effectiveness and Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santana, L.S.; Gallo, R.B.S.; Ferreira, C.H.J.; Duarte, G.; Quintana, S.M.; Marcolin, A.C. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) reduces pain and postpones the need for pharmacological analgesia during labour: A randomised trial. J. Physiother. 2015, 62, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levett, K.; Smith, C.; Dahlen, H.; Bensoussan, A. Acupuncture and acupressure for pain management in labour and birth: A critical narrative review of current systematic review evidence. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutshi, V.; Rani, K.U.; Marwah, S.; Patel, M. Efficacy of intravenous infusion of acetaminophen for intrapartum analgesia. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2016, 10, QC18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, M.; Pevzner, L.; Schmuel, E.; Bernstein, P.; Dayal, A.; Barnhard, J.; Chazotte, C.; Merkatz, I. Uterine tachysystole and hyperstimulation during induction of labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Neophytou, M.; Hars, O.; Freudenberg, J.; Kühnert, M. Clinical experience with misoprostol vaginal insert for induction of labor: A prospective clinical observational study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahimi, M.; Haghighi, L.; Baradaran, H.R.; Azami, M.; Larijani, S.S.; Kazemzadeh, P.; Moradi, Y. Comparison of the effect of oral and vaginal misoprostol on labor induction: Updating a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| <37 Group (n = 42) | 37–41 Group (n = 76) | +41 Group (n = 72) | All (n = 190) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 35.1 (0.7) | 38.5 (1.2) | 41.1 (0.3) | 38.8 (2.4) | a–c <0.0001 3 |

| Range | 34.0–36.0 | 37.0–40.0 | 41.0–42.0 | 34.0–42.0 | |

| Median | 35.0 a,b | 38.0 a,c | 41.0 b,c | 40.0 | |

| 95% CI | [34.9; 35.4] | [38.2; 38.8] | [41.1; 41.2] | [38.4; 39.1] | |

| Time to delivery | a | b | c | ||

| 24 h | 27 (64.3%) | 61 (80.3%) | 64 (88.9%) | 152 (80.0%) | a,b 0.1064 4 |

| 24–48 h | 6 (14.3%) | 7 (9.2%) | 5 (6.9%) | 18 (9.5%) | a–c 0.0038 1,4 |

| Up to 48 h | 33 (78.6%) | 68 (89.5%) | 69 (95.8%) | 170 (89.5%) | b,c 0.7971 4 |

| >48 h | 9 (21.4%) | 8 (10.5%) | 3 (4.2%) | 20 (10.5%) | |

| Delivery type | a | b | c | a,b 0.7422 4 | |

| Vaginal | 23 (54.8%) | 44 (57.9%) | 44 (61.1%) | 111 (58.4%) | a–c 0.0016 4 |

| Cesarean section (CS) | 19 (45.2%) | 32 (42.1%) | 28 (38.9%) | 79 (41.6%) | b,c 0.6904 4 |

| <37 Group (n = 23) | 37–41 Group (n = 44) | +41 Group (n = 44) | All (n = 111) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to vaginal delivery | a | b | c | a,b 0.2088 4,3 | |

| 24 h | 15 (65.3%) | 41 (93.2%) | 43 (97.7%) | 99 (89.2%) | a–c 0.0142 1,4, |

| 24–48 h | 5 (21.7%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (2.3%) | 7 (6.3%) | b,c 0.1526 2,4 |

| up to 48 h | 20 (87.0%) | 42 (95.5%) | 44 (100.0%) | 106 (95.5%) | |

| >48 h | 3 (13.0%) | 2 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| <37 Group (n = 19) | 37–41 Group (n = 32) | +41 Group (n = 28) | All (n = 79) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to delivery by cesarean section | a | b | c | a,b 0.2964 4,3 | |

| 24 h | 12 (63.2%) | 20 (62.4%) | 21 (75.0%) | 53 (67.1%) | a–c <0.0001 1,4 |

| 24–48 h | 1 (5.2%) | 6 (18.8%) | 4 (14.3%) | 11 (13.9%) | b,c 0.3845 2,4 |

| up to 48 h | 13 (68.4%) | 26 (81.2%) | 25 (89.3%) | 64 (81.0%) | |

| >48 h | 6 (31.6%) | 6 (18.8%) | 3 (10.7%) | 15 (19.0%) |

| <37 Group (n = 19) | 37–41 Group (n = 32) | +41 Group (n = 28) | All (n = 79) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal CTG record | a | b | c | a,b 0.2322 4,1 | |

| TOTAL | 8 (42.1%) | 19 (59.4%) | 20 (71.4%) | 47 (59.5%) | a–c 0.0019 2,4 |

| b,c 0.5121 4 | |||||

| 24 h | 7 (87.5%) | 16 (84.2%) | 15 (75.0%) | 38 (80.8%) | a,b 0.2322 3,4 |

| 24–48 h | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) | 4 (20.0%) | 6 (12.8%) | a–c 0.4863 4 |

| up to 48 h | 7 (87.5%) | 18 (94.7%) | 19 (95.0%) | 44 (93.6%) | b,c 0.9703 4 |

| >48 h | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (5.0%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| <37 Group (n = 19) | 37–41 Group (n = 32) | +41 Group (n = 28) | All (n = 79) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to labor progression | a | b | c | a,b 0.2322 4,1 | |

| TOTAL | 11 (57.9%) | 13 (40.6%) | 8 (28.6%) | 32 (40.5%) | a–c 0.0019 2,4 |

| b,c 0.3288 4 | |||||

| 24 h | 5 (45.5%) | 4 (30.8%) | 6 (75.0%) | 15 (46.9%) | a,b 0.72923 3,4 |

| 24–48 h | 1 (9.0%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (15.6%) | a–c 0.3615 4 |

| up to 48 h | 6 (54.5%) | 8 (61.6%) | 6 (75.0%) | 20 (62.5%) | b,c 0.5251 4 |

| >48 h | 5 (45.5%) | 5 (38.4%) | 2 (25.0%) | 12 (37.5%) |

| <37 Group (n = 42) | 37–41 Group (n = 76) | +41 Group (n = 72) | All (n = 190) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytocin use | a | b | c | a,b 0.0563 4,1 | |

| TOTAL | 15 (35.7%) | 15 (19.7%) | 8 (11.1%) | 38 (20.0%) | a–c 0.0016 2,4 |

| b,c 0.1477 4 | |||||

| a | b | c | a,b 0.7125 4 | ||

| 24–48 h | 6 (40.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 18 (47.4%) | a–c 0.3036 3,4 |

| 48 h | 9 (60.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 20 (52.6%) | b,c 0.4691 4 |

| Intrapartum analgesia (Remifentanyl) | a | b | c | a,b 0.5637 4 | |

| TOTAL | 33 (78.6%) | 63 (82.9%) | 60 (83.3%) | 156 (82.1%) | a–c 0.5270 4 |

| b,c 0.9433 4 | |||||

| a | b | c | a,b0.0924 4 | ||

| 24 h | 25 (75.8%) | 56 (88.9%) | 58 (96.7%) | 139 (89.1%) | a–c 0.0018 4 |

| 24–48 h | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | b,c 0.0978 4 |

| >48 h | 8 (24.2%) | 7 (11.1%) | 2 (3.3%) | 17 (10.9%) |

| <37 Group (n = 42) | 37–41 Group (n = 76) | +41 Group (n = 72) | All (n = 190) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence of tachysystole | a | b | c | a,b 0.5169 | |

| TOTAL | 2 (4.8%) | 6 (7.9%) | 4 (5.6%) | 12 (6.3%) | a–c 0.8548 4 |

| b,c 0.5709 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Socha, M.W.; Flis, W.; Wartęga, M.; Stankiewicz, M.; Kunicka, A. The Efficacy of Misoprostol Vaginal Inserts for Induction of Labor in Women with Very Unfavorable Cervices. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124106

Socha MW, Flis W, Wartęga M, Stankiewicz M, Kunicka A. The Efficacy of Misoprostol Vaginal Inserts for Induction of Labor in Women with Very Unfavorable Cervices. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(12):4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124106

Chicago/Turabian StyleSocha, Maciej W., Wojciech Flis, Mateusz Wartęga, Martyna Stankiewicz, and Aleksandra Kunicka. 2023. "The Efficacy of Misoprostol Vaginal Inserts for Induction of Labor in Women with Very Unfavorable Cervices" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 12: 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124106

APA StyleSocha, M. W., Flis, W., Wartęga, M., Stankiewicz, M., & Kunicka, A. (2023). The Efficacy of Misoprostol Vaginal Inserts for Induction of Labor in Women with Very Unfavorable Cervices. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(12), 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124106