Factors Impacting the Use or Rejection of Hearing Aids—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Qualitative and Quantitative Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

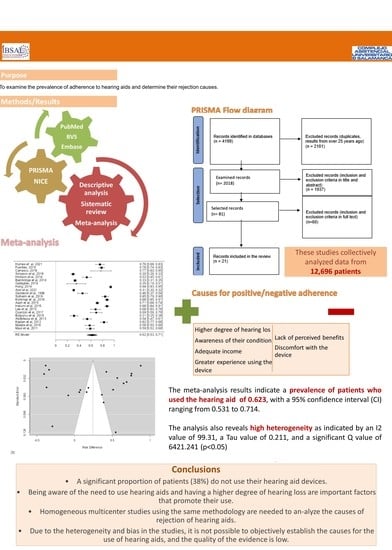

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

- A significant proportion of patients (38%) do not use their hearing aid devices.

- Being aware of the need to use hearing aids and having a higher degree of hearing loss are important factors that promote their use.

- Homogeneous multicenter studies using the same methodology are needed to analyze the causes of rejection of hearing aids.

- Due to the heterogeneity and bias in the studies, it is not possible to objectively establish the causes for the use of hearing aids, and the quality of the evidence is low. There is heterogeneity among the studies included in this analysis, including non-randomized series, variation in the populations studied, different study designs, and diverse data collection methods. The wide age range and the inclusion of studies conducted over a long period, which encompasses changes in technology and social habits, further contribute to the heterogeneity. This increased heterogeneity suggests that the results may not apply to the overall population. Therefore, valid conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the characteristics and profiles of patients in each group.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cano, C.A.; Borda, M.G.; Arciniegas, A.J.; Parra, J.S. Problemas de la audición en el adulto mayor, factores asociados y calidad de vida: Estudio SABE Bogotá, Colombia. Biomedica 2014, 34, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabello, P.; Bahamonde, H. El adulto mayor y la patología otorrinolaringológica. Rev. Hosp. Clín. Univ. Chile 2008, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Restrepo, M.S.; Morales, G.R.; Ramírez, G.M.; López, L.M.; Varela, L.L. Los hábitos alimentarios en adultos mayores y su relación con los procesos protectores y deteriorantes de la salud. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2006, 33, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete, S.O.; Gallardo, A.L. Descripción de factores no audiológicos asociados en adultos mayores del programa de audífonos año 2006, Hospital Padre Hurtado, Santiago. Rev. Otorrinolaringol. Cir. Cabeza Cuello 2009, 69, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, M.A.; Kitterick, P.T.; Chong, L.Y.; Edmondson-Jones, M.; Barker, F.; Hoare, D.J. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, C.; Aguilera, E.; Lecaros, R.; Riquelme, K.; Valenzuela, M.; Manque, P. No adherencia al uso de audífonos en adultos mayores de 65 años. Programa GES, hospital Carlos Van Buren, 2014. Rev. Chil. Salud Pública 2014, 19, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GBD 2019 Hearing Loss Collaborators. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 397, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.E.; Rankin, Z.; Noonan, K.Y. Otolaryngology and the Global Burden of Disease. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2018, 51, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, L.; Hamilton, L.; Orange, S.P. Factors associated with hearing aid use. Aust. J. Audiol. 1986, 8, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Maul, F.X.; Rivera, B.C.; Aracena, C.K.; Slater, R.F.; Breinbauer, K.H. Adherencia y desempeño auditivo en uso de audífonos en pacientes adultos hipoacúsicos atendidos en la Red de Salud UC. Rev. Otorrinolaringol. Cir. Cabeza Cuello 2011, 71, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kochkin, S.; Beck, D.L.; Christensen, A.L.A.; Medwetsky, L.; Northern, J.; Sweetow, R. MarkeTrak VIII: Why Consumers Return Hearing Aids: A Guide for Reducing Hearing Aid Returns; Better Hearing Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aazh, H.; Prasher, D.; Nanchahal, K.; Moore, B.C. Hearing-aid use and its determinants in the UK National Health Service: A cross-sectional study at the Royal Surrey County Hospital. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, H.; Day, J.; Bant, S.; Munro, K.J. Adoption, use and non-use of hearing aids: A robust estimate based on Welsh national survey statistics. Int. J. Audiol. 2020, 59, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, C.; Hickson, L.; Fletcher, A. Identifying the barriers and facilitators to optimal hearing aid self-efficacy. Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53 (Suppl. 1), S28–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.H.; Loke, A.Y. Determinants of hearing-aid adoption and use among the elderly: A systematic review. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing Review Questions and Planning the Evidence Review. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/developing-review-questions-and-planning-the-evidence-review (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Van der Mierden, S.; Tsaioun, K.; Bleich, A.; Leenaars, C.H.C. Software tools for literature screening in systematic reviews in biomedical research. ALTEX 2019, 36, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humes, L.E. Differences Between Older Adults Who Do and Do Not Try Hearing Aids and Between Those Who Keep and Return the Devices. Trends Hear. 2021, 25, 23312165211014329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-López, E.; Fuente, A.; Valdivia, G.; Luna-Monsalve, M. Effects of auditory and socio-demographic variables on discontinuation of hearing aid use among older adults with hearing loss fitted in the Chilean public health sector. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrasco-Alarcón, P.; Morales, C.; Bahamóndez, M.C.; Cárcamo, D.A.; Schacht, C. Elderly who refuse to use hearing aids: An analysis of the causes. Codas 2018, 30, e20170198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpson, A.N.; Matthews, L.J.; Cassarly, C.; Dubno, J.R. Time from Hearing Aid Candidacy to Hearing Aid Adoption: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickson, L.; Meyer, C.; Lovelock, K.; Lampert, M.; Khan, A. Factors associated with success with hearing aids in older adults. Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53 (Suppl. 1), S18–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, K.E.; Ramachandran, V. Hearing aid use among older U.S. adults; the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2005–2006 and 2009–2010. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallagher, N.E.; Woodside, J.V. Factors Affecting Hearing Aid Adoption and Use: A Qualitative Study. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2018, 29, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.Y.; Oh, I.-H.; Jung, T.S.; Kim, T.H.; Kang, H.M.; Yeo, S.G. Clinical Reasons for Returning Hearing Aids. Korean J. Audiol. 2014, 18, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assi, L.; Reed, N.S.; Nieman, C.L.; Willink, A. Factors Associated with Hearing Aid Use Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, igab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garstecki, D.C.; Erler, S.F. Hearing loss, control, and demographic factors influencing hearing aid use among older adults. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 1998, 41, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, J.; Gay, C.; Hickson, L. Older adults’ experiences and issues with hearing aids in the first six months after hearing aid fitting. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.H.; Bayır, Ö.; Er, S.; Işık, E.; Saylam, G.; Tatar, E.; Özdek, A. Satisfaction and compliance of adult patients using hearing aid and evaluation of factors affecting them. Eur. Arch. Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2016, 273, 3723–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, I.D.S.; Shirayama, Y.; Yuasa, M.; Bento, R.F.; Iwahashi, J.H. Hearing Aid Use and Adherence to Treatment in a Publicly-Funded Health Service from the City of São Paulo, Brazil. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 19, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.-H.; Noh, H. Prediction of the use of conventional hearing aids in Korean adults with unilateral hearing impairment. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyarzún, P.D.; Quilaqueo, D.S. Adherencia y caracterización de la población de adultos mayores usuarios de audífonos atendidos en el Servicio de Otorrinolaringología del Hospital Regional de Talca. Rev. Otorrinolaringol. Cir. Cabeza Cuello 2017, 77, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bulğurcu, S.; Uçak, I.; Yönem, A.; Erkul, E.; Çekin, E. Hearing Aid Problems in Elderly Populations. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020, 99, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdellaoui, A.; Huy, P.T.B. Success and failure factors for hearing-aid prescription: Results of a French national survey. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2013, 130, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan-Neeman, R.; Muchnik, C.; Hildesheimer, M.; Henkin, Y. Hearing aid satisfaction and use in the advanced digital era. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Sugaya, A.; Nagayasu, R.; Nakagawa, A.; Nishizaki, K. Subjective hearing-related quality-of-life is a major factor in the decision to continue using hearing aids among older persons. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2016, 136, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Stephens, D. Reasons for referral and attitudes toward hearing aids: Do they affect outcome? Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 2003, 28, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, L.V.; Öberg, M.; Nielsen, C.; Naylor, G.; Kramer, S.E. Factors Influencing Help Seeking, Hearing Aid Uptake, Hearing Aid Use and Satisfaction with Hearing Aids: A Review of the Literature. Trends Amplif. 2010, 14, 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCormack, A.; Fortnum, H. Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? Int. J. Audiol. 2013, 52, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nieman, C.L.; Marrone, N.; Szanton, S.L.; Thorpe, J.R.J.; Lin, F.R. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Hearing Health Care Among Older Americans. J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomita, M.; Mann, W.C.; Welch, T.R. Use of assistive devices to address hearing impairment by older persons with disabilities. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2001, 24, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.N. The time course of adaptation to hearing aid use. Br. J. Audiol. 1996, 30, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruusuvuori, J.E.; Aaltonen, T.; Koskela, I.; Ranta, J.; Lonka, E.; Salmenlinna, I.; Laakso, M. Studies on stigma regarding hearing impairment and hearing aid use among adults of working age: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Barker, T.H.; Ziegelmann, P.K.; Munn, Z.; Falavigna, M. Meta-analysis of prevalence: I2 statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoli, S.; Staehelin, K.; Zemp, E.; Schindler, C.; Bodmer, D.; Probst, R. Survey on hearing aid use and satisfaction in Switzerland and their determinants. Int. J. Audiol. 2009, 48, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Database | Boolean Operators |

|---|---|

| EMBASE | (‘hearing aid’/exp OR ‘hearing aid’ OR ((‘hearing’/exp OR hearing) AND (‘aid’/exp OR aid))) AND (‘adaptation’/exp OR adaptation) (‘hearing aid’/exp OR ‘hearing aid’ OR ((‘hearing’/exp OR hearing) AND (‘aid’/exp OR aid))) AND (‘patient compliance’/exp OR ‘patient compliance’) ((‘hearing aid’/exp OR ‘hearing aid’ OR ((‘hearing’/exp OR hearing) AND (‘aid’/exp OR aid))) AND (‘patient compliance’/exp OR ‘patient compliance’) OR ‘acceptance’/exp OR acceptance) AND (‘older adults’/exp OR ‘older adults’) (‘hearing aid’/exp OR ‘hearing aid’ OR ((‘hearing’/exp OR hearing) AND (‘aid’/exp OR aid))) AND (‘acceptance’/exp OR acceptance) AND (‘older adults’/exp OR ‘older adults’) (‘aged’/exp OR ‘aged’ OR ‘aged patient’ OR ‘aged people’ OR ‘aged person’ OR ‘aged subject’ OR ‘elderly’ OR ‘elderly patient’ OR ‘elderly people’ OR ‘elderly person’ OR ‘elderly subject’ OR ‘senior citizen’ OR ‘senium’) AND (‘hearing aid’/exp OR ‘aid, hearing’ OR ‘auditory appliance’ OR ‘auditory prosthesis’ OR ‘fitting, hearing aid’ OR ‘hearing aid’ OR ‘hearing aid device’ OR ‘hearing aid fitting’ OR ‘hearing aid, device’ OR ‘hearing aids’ OR ‘hearing apparatus’ OR ‘hearing device’ OR ‘listening aid’ OR ‘listening aids’) AND (‘patient compliance’/exp OR ‘adherence to therapy’ OR ‘adherence to treatment’ OR ‘compliance to therapy’ OR ‘compliance to treatment’ OR ‘patient adherence’ OR ‘patient compliance’ OR ‘patients’ adherence’ OR ‘therapy adherence’ OR ‘therapy compliance’ OR ‘treatment adherence’ OR ‘treatment adherence and compliance’ OR ‘treatment compliance’) |

| PUBMED | hearing aid AND older adults AND patient compliance hearing aid AND elderly AND use hearing aid and elderly and use hearing aid and elderly and adherence hearing aid and elderly and acceptance hearing aid and elderly and acceptance hearing aid and use and covid hearing aid AND elderly AND (use OR adherence OR acceptance OR Patient compliance) |

| BVS | hearing aid and elderly and patient compliance hearing aid and elderly and acceptance hearing aid and elderly and adherence |

| Author, Year | Total No. | Adherence (n) | Rejection n (Rate) | AVG. AGE | Min. Age | Max. Age | Avg. Age Use | Avg. Age Rejection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humes et al., 2021 [20] | Retrospective | 139 | 105 | 34 (24%) | 73.7 | 60 | 89 | 74.7 | 72.7 |

| Fuentes-López, 2019 [21] | Prospective | 355 | 278 | 77 (22%) | 74.9 | 65 | 85 | ||

| Carrasco-Alarcón, 2018 [22] | Cross-sectional | 22 | 18 | 5 (22%) | 79.6 | 60 | 99 | 79 | 80.2 |

| Simpson et al., 2019 [23] | Prospective | 732 | 218 | 514 (70%) | 70.1 | 18 | x | 69.1 | 70.2 |

| Hickson et al., 2014 [24] | Retrospective | 160 | 85 | 75 (46%) | 73 | 60 | 91 | ||

| Bainbridge et al., 2014 [25] | Cross-sectional | 1636 | 541 | 1095 (33%) | 70 | ||||

| Gallagher, 2018 [26] | Cross-sectional | 32 | 12 | 22 (64%) | 71.6 | 47 | 80 | 71.5 | 76.7 |

| Hong, 2014 [27] | Retrospective | 1318 | 1237 | 81 (6%) | 65.3 | ||||

| Assi et al., 2021 [28] | Cross-sectional | 5146 | 1587 | 3559 (69%) | |||||

| Garstecki et al., 1998 [29] | Cross-sectional | 131 | 60 | 71 (54%) | 74.5 | 65 | 90 | 75.35 | 73.7 |

| Solheim et al., 2019 [30] | Prospective | 181 | 153 | 28 (15%) | 79.2 | 60 | |||

| Korkmaz et al., 2016 [31] | Retrospective | 400 | 351 | 49 (12%) | 63.67 | 39 | 89 | ||

| Aazh et al., 2015 [12] | Cross-sectional | 1023 | 727 | 296 (28%) | 74 | 75 | 73 | ||

| Harumi et al., 2015 [32] | Cross-sectional | 305 | 267 | 38 (12%) | 69 | 21 | 101 | 71.33 | 69.71 |

| Lee et al., 2015 [33] | Retrospective | 119 | 81 | 38 (31%) | 58 | 19 | 81 | 61.4 | 57.3 |

| Oyarzún et al., 2017 [34] | Cross-sectional | 78 | 54 | 24 (30%) | 77.4 | 65 | |||

| Bulgurcu et al., 2019 [35] | Retrospective | 191 | 60 | 131 (68%) | 77.54 | 60 | |||

| Abdellaoui et al., 2013 [36] | Prospective | 184 | 99 | 85 (46%) | 74.2 | 55 | 92 | ||

| Kaplan-Neeman et al., 2012 [37] | Cross-sectional | 177 | 146 | 31 (17%) | 65.7 | 49 | 65.2 | 66.2 | |

| Maeda et al., 2016 [38] | Retrospective | 157 | 91 | 66 (42%) | 75.3 | 65 | 74.6 | 76.1 | |

| Maul et al., 2011 [10] | Cross-sectional | 208 | 123 | 85 (40%) | 74.6 | 65 |

| Author, Year | Causes for Use | Causes for Rejection | Causes for Use Legend | Causes for Rejection Legend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humes et al., 2021 [20] | 1, 2 | 1: a higher degree of hearing loss (in each article screened, they classify the degree of hearing differently) or bilateral hearing loss. 2: greater awareness of their condition. 3: greater satisfaction with the device, ease of use of the device, or having a simpler or more modern device. 4: higher economic status, higher income, higher level of education, having a university degree (each article examined determined in a different way the economic level qualified as high). 5: social issues (working age, daily activity, difficulties communicating in daily life, social support). 6: emotional causes, having a positive attitude. 7: greater experience using the device, using the device more hours per day. 8: being caucasian 9: recent diagnosis, recent audiometry evaluation, regular medical monitoring. 10: older age. 11: being male. 12: other comorbidities. | 1: lack of awareness of their condition. 2: low or no perceived benefits from hearing aid use. 3: inability to understand others. 4: finding the device uncomfortable or difficult to use. 5: social stigma and other social causes. 6: lack of sufficient income. 7: lack of social or family support. 8: older age. | |

| Fuentes-López, 2019 [21] | 2, 3, 4 | 2, 3, 4 | ||

| Carrasco-Alarcón, 2018 [22] | 2, 3, 4 | |||

| Simpson et al., 2019 [23] | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 | |||

| Hickson et al., 2014 [24] | 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 | 2, 3 | ||

| Bainbridge et al., 2014 [25] | 1, 2, 4, 9 | |||

| Gallagher, 2018 [26] | 1, 2, 5, 7, 10 | 2, 3, 4, 5 | ||

| Hong, 2014 [27] | 2, 3, 4, 6 | |||

| Assi et al., 2021 [28] | 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12 | |||

| Garstecki et al., 1998 [29] | 1, 2 | 5, 7 | ||

| Solheim et al., 2019 [30] | 2, 12 | 2, 4 | ||

| Korkmaz et al., 2016 [31] | 1, 7 | |||

| Aazh et al., 2015 [12] | 1, 10 | 3, 2 | ||

| Harumi et al., 2015 [32] | 7, 4 | |||

| Lee et al., 2015 [33] | 3, 5 | |||

| Oyarzún et al., 2017 [34] | 1 | |||

| Bulgurcu et al., 2019 [35] | 2, 3, 4, 6 | |||

| Abdellaoui et al., 2013 [36] | 2, 3, 5 | 2, 6 | ||

| Kaplan-Neeman et al., 2012 [37] | 1, 7, 10 | |||

| Maeda et al., 2016 [38] | 6 | |||

| Maul et al., 2011 [10] | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcos-Alonso, S.; Almeida-Ayerve, C.N.; Monopoli-Roca, C.; Coronel-Touma, G.S.; Pacheco-López, S.; Peña-Navarro, P.; Serradilla-López, J.M.; Sánchez-Gómez, H.; Pardal-Refoyo, J.L.; Batuecas-Caletrío, Á. Factors Impacting the Use or Rejection of Hearing Aids—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124030

Marcos-Alonso S, Almeida-Ayerve CN, Monopoli-Roca C, Coronel-Touma GS, Pacheco-López S, Peña-Navarro P, Serradilla-López JM, Sánchez-Gómez H, Pardal-Refoyo JL, Batuecas-Caletrío Á. Factors Impacting the Use or Rejection of Hearing Aids—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(12):4030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124030

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcos-Alonso, Susana, Cristina Nicole Almeida-Ayerve, Chiara Monopoli-Roca, Guillermo Salib Coronel-Touma, Sofía Pacheco-López, Paula Peña-Navarro, José Manuel Serradilla-López, Hortensia Sánchez-Gómez, José Luis Pardal-Refoyo, and Ángel Batuecas-Caletrío. 2023. "Factors Impacting the Use or Rejection of Hearing Aids—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 12: 4030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124030

APA StyleMarcos-Alonso, S., Almeida-Ayerve, C. N., Monopoli-Roca, C., Coronel-Touma, G. S., Pacheco-López, S., Peña-Navarro, P., Serradilla-López, J. M., Sánchez-Gómez, H., Pardal-Refoyo, J. L., & Batuecas-Caletrío, Á. (2023). Factors Impacting the Use or Rejection of Hearing Aids—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(12), 4030. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124030