Feasibility and Acceptability of a Complex Telerehabilitation Intervention for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury: The Child in Context Intervention (CICI)

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment Procedures

2.3. Assessments

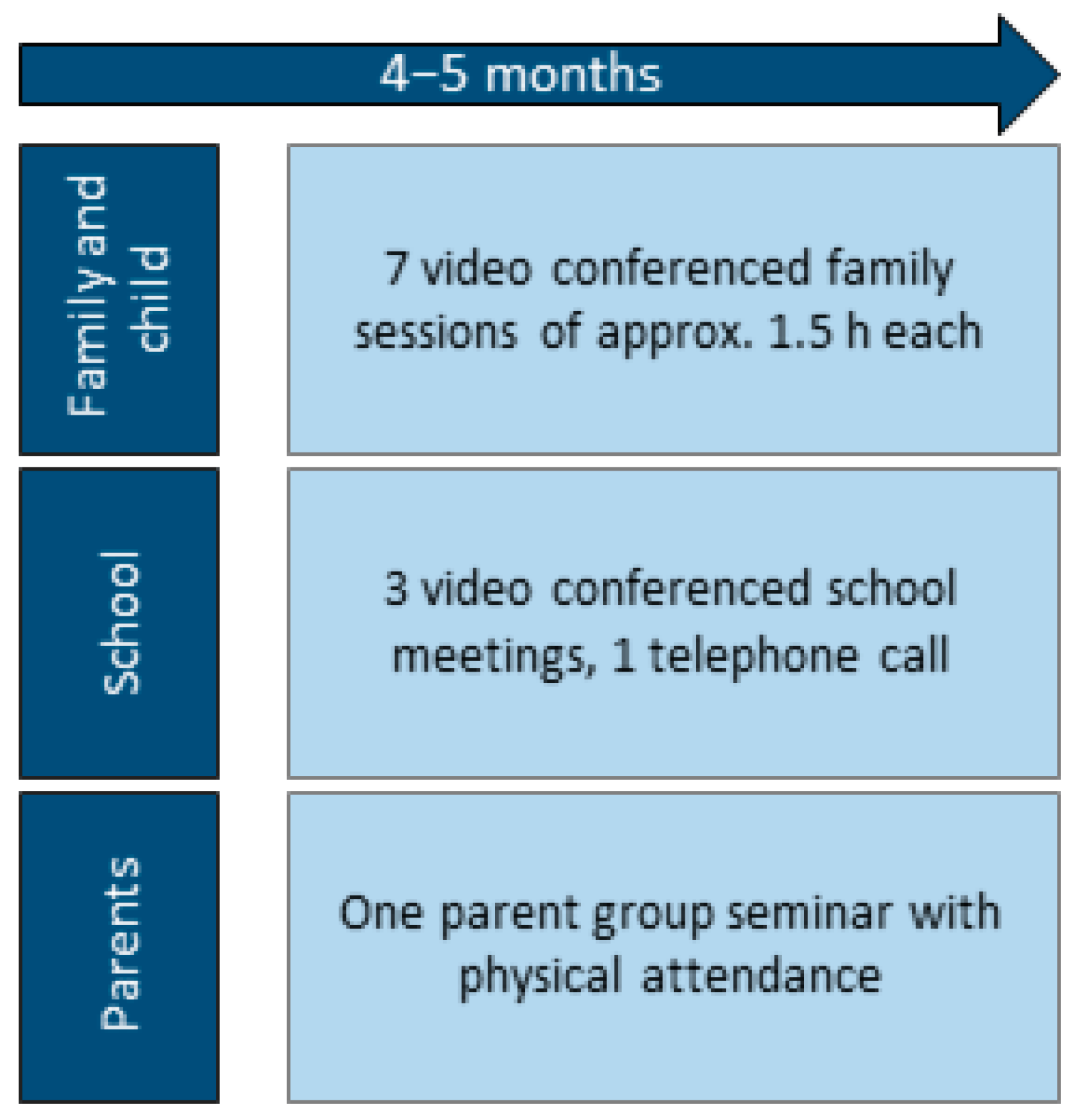

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Content

2.5.1. Family Sessions

2.5.2. School Involvement

2.5.3. Parent Group Seminar

2.6. Telerehabilitation Delivery

2.7. Adaptations Due to COVID-19

2.8. Procedures of Feasibility Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Identification of Main pABI-Related Problem Areas

3.2. Objective 1: Recruitment Procedures

3.3. Objective 2: Contents and Structure of the Intervention

3.3.1. Attendance

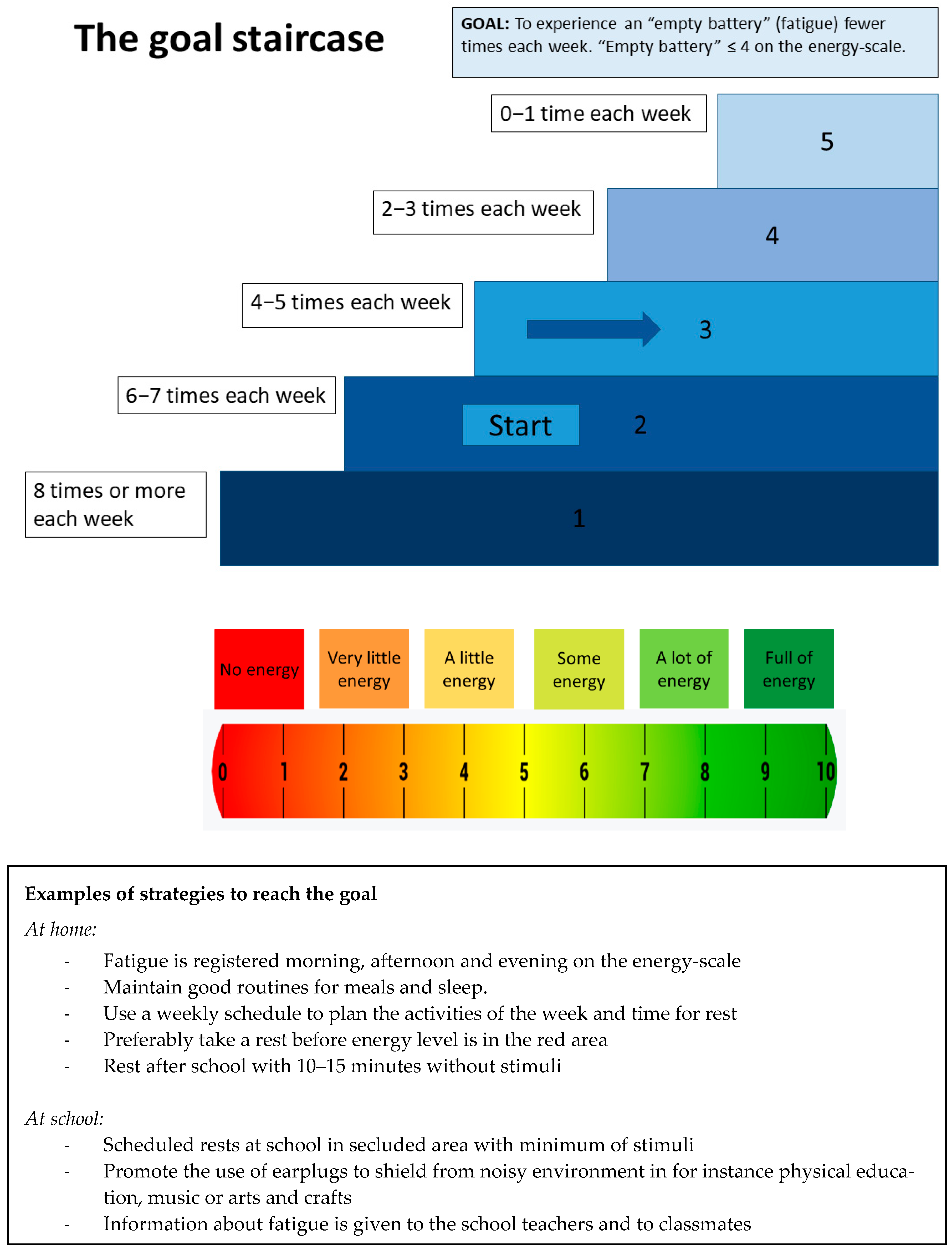

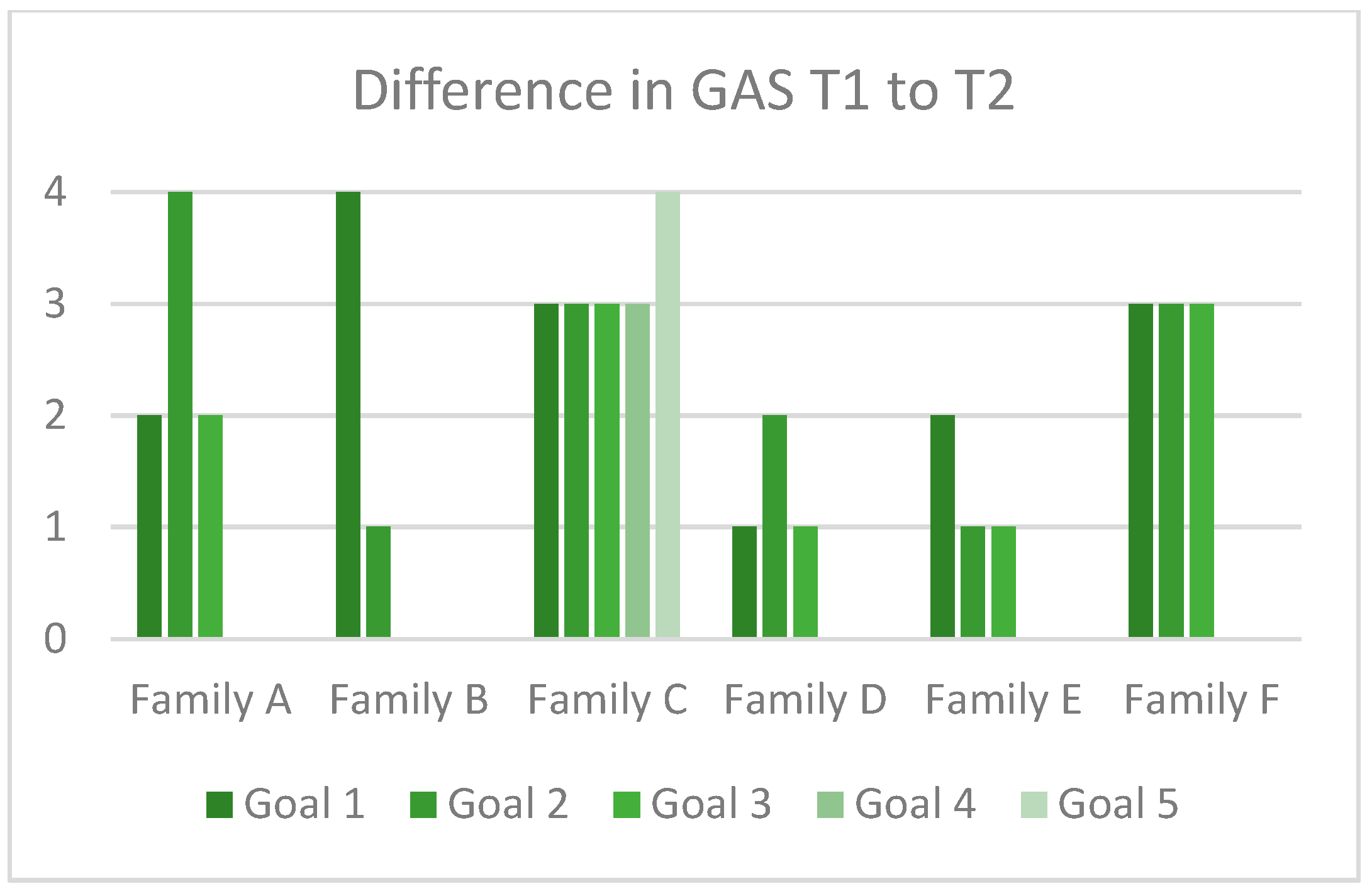

3.3.2. Evaluation of the SMART-Goal and GAS Approach

3.3.3. Responses to the SMART-Goal Approach

3.3.4. The Use of Videoconferences in Treatment Delivery

3.4. Objective 3: Acceptability for the Children, Parents and Therapists

3.4.1. Working Alliance in the Intervention

3.4.2. Usefulness of the Intervention

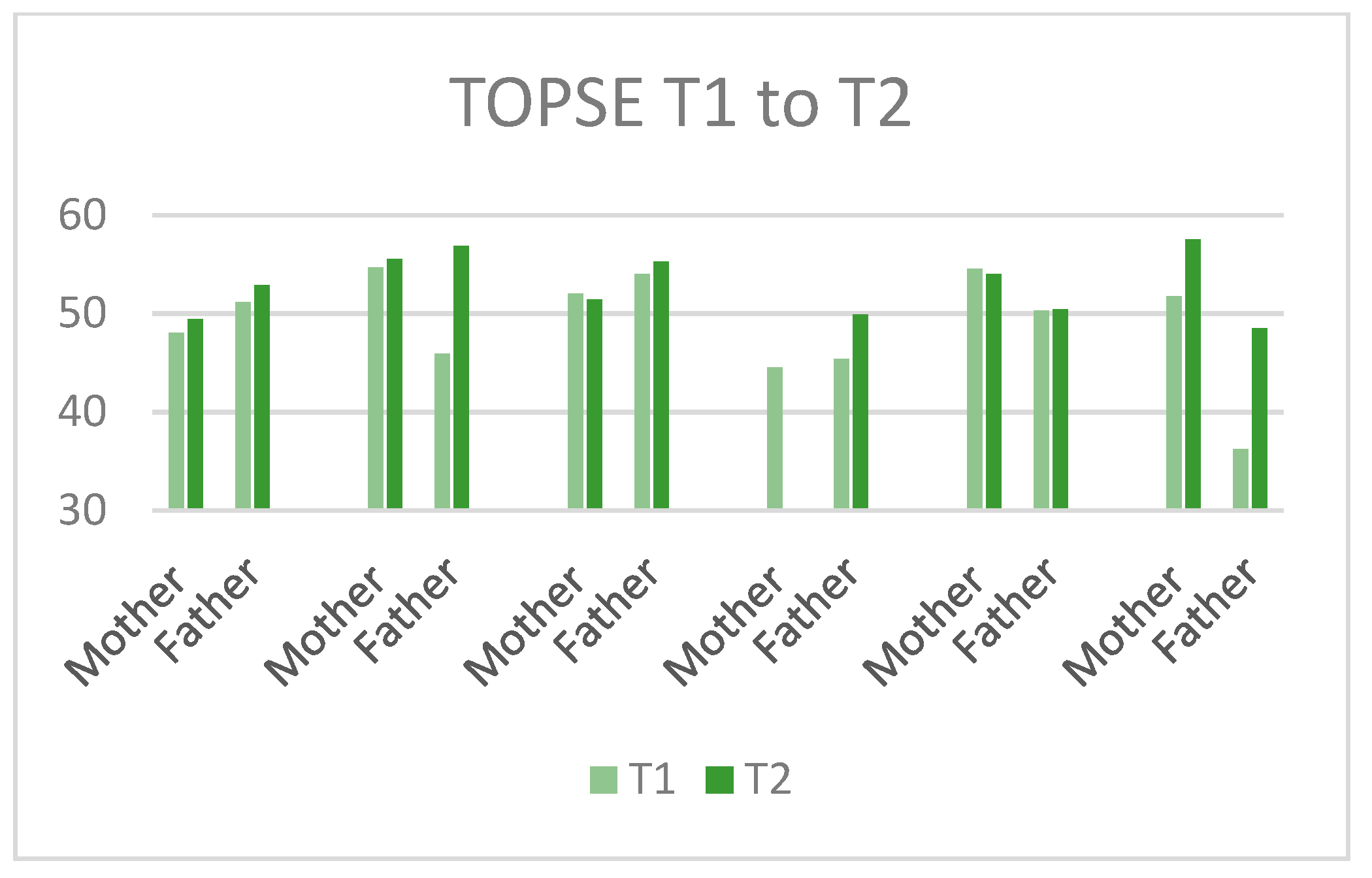

3.5. Objective 4: Methods of Assessment at Baseline and T2

3.5.1. Burden of Assessments

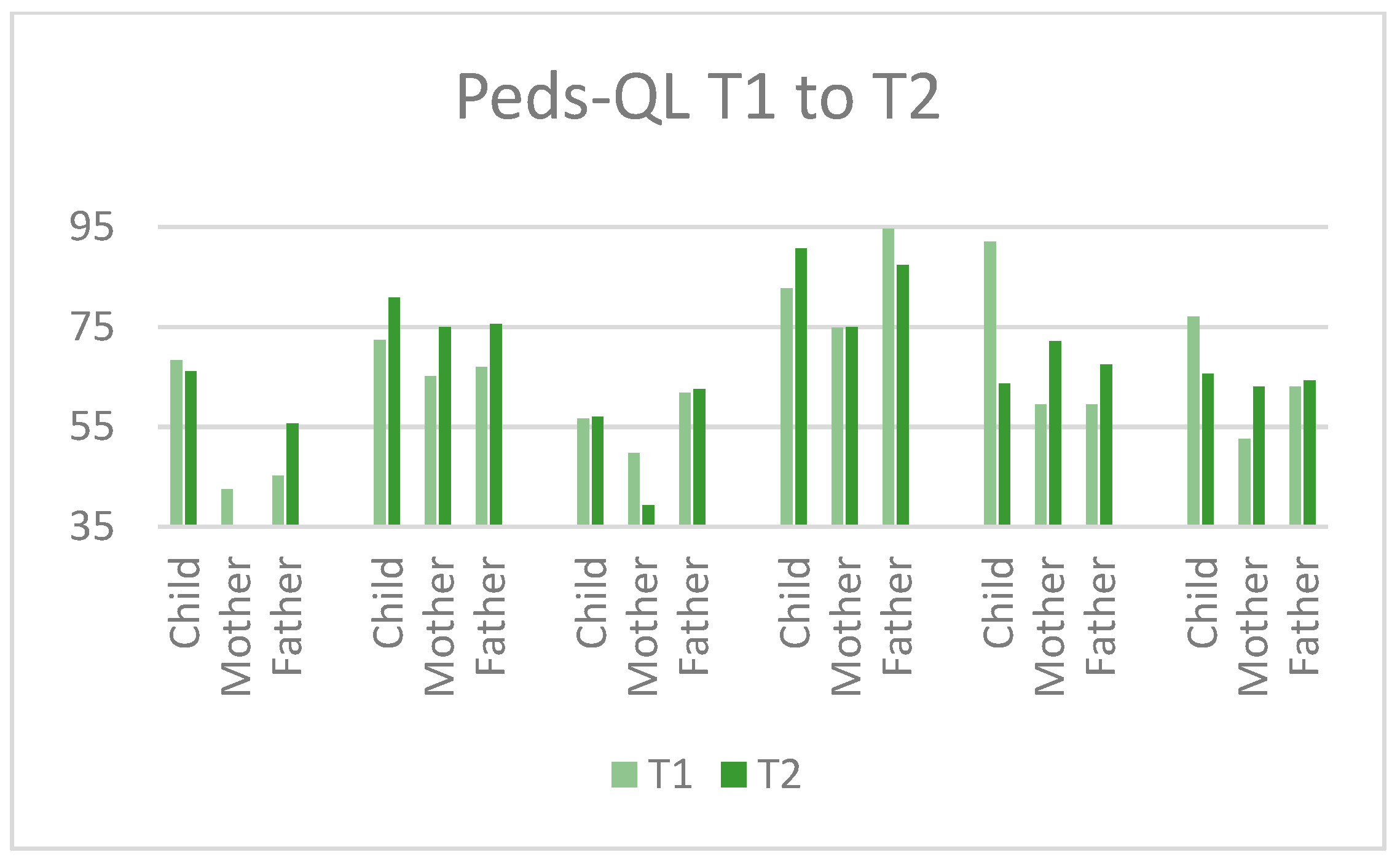

3.5.2. Outcome Measures

3.6. Objective 5: Quality of Treatment Delivery

3.7. Harms

4. Discussion

4.1. Contents and Structure of the Intervention

4.2. Acceptability

4.3. Methods of Assessment at Baseline and Post Treatment

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, V.; Brown, S.; Newitt, H.; Hoile, H. Long-term outcome from childhood traumatic brain injury: Intellectual ability, personality, and quality of life. Neuropsychology 2011, 25, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babikian, T.; Asarnow, R. Neurocognitive outcomes and recovery after pediatric TBI: Meta-analytic review of the literature. Neuropsychology 2009, 23, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babikian, T.; Merkley, T.; Savage, R.C.; Giza, C.C.; Levin, H. Chronic Aspects of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Review of the Literature. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Câmara-Costa, H.; Francillette, L.; Opatowski, M.; Toure, H.; Brugel, D.; Laurent-Vannier, A.; Meyer, P.G.; Dellatolas, G.; Watier, L.; Chevignard, M. Participation seven years after severe childhood traumatic brain injury. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 42, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, M.; Anaby, D.; DeMatteo, C.; Hanna, S. Participation patterns of children with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2011, 25, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivara, F.P.; Ennis, S.K.; Mangione-Smith, R.; MacKenzie, E.J.; Jaffe, K.M. Quality of Care Indicators for the Rehabilitation of Children with Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 381–385.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Battista, A.; Soo, C.; Catroppa, C.; Anderson, V. Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents Post-TBI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosema, S.; Crowe, L.; Anderson, V. Social Function in Children and Adolescents after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review 1989–2011. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keetley, R.; Radford, K.; Manning, J. A scoping review of the needs of children and young people with acquired brain injuries and their families. Brain Inj. 2019, 33, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, H.T.; Clark, A.E.; Holubkov, R.; Ewing-Cobbs, L. Changing Healthcare and School Needs in the First Year After Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2020, 35, E67–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Davis, N.; Tyson, S.F. A scoping review of the needs of children and other family members after a child’s traumatic injury. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, D.T. What is rehabilitation? An empirical investigation leading to an evidence-based description. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF-CY; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McCarron, R.H.; Watson, S.; Gracey, F. What do Kids with Acquired Brain Injury Want? Mapping Neuropsychological Rehabilitation Goals to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2019, 25, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laatsch, L.; Dodd, J.; Brown, T.; Ciccia, A.; Connor, F.; Davis, K.; Doherty, M.; Linden, M.; Locascio, G.; Lundine, J.; et al. Evidence-based systematic review of cognitive rehabilitation, emotional, and family treatment studies for children with acquired brain injury literature: From 2006 to 2017. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 130–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catroppa, C.; Anderson, V. Traumatic brain injury in childhood: Rehabilitation considerations. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2009, 12, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catroppa, C.; Soo, C.; Crowe, L.; Woods, D.; Anderson, V. Evidence-based approaches to the management of cognitive and behavioral impairments following pediatric brain injury. Future Neurol. 2012, 7, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Arana, C.; Catroppa, C.; Carranza-Escárcega, E.; Godfrey, C.; Yáñez-Téllez, G.; Corona, P.; De León, M.A.; Anderson, V. A Systematic Review of Interventions for Hot and Cold Executive Functions in Children and Adolescents with Acquired Brain Injury. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.L.; Fisher, A.P.; Kaizar, E.E.; Yeates, K.O.; Taylor, H.G.; Zhang, N. Recovery Trajectories of Child and Family Outcomes Following Online Family Problem-Solving Therapy for Children and Adolescents after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2019, 25, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.L.; Kaizar, E.E.; Narad, M.; Zang, H.; Kurowski, B.G.; Yeates, K.O.; Taylor, H.G.; Zhang, N. Online Family Problem-solving Treatment for Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Kaizar, E.E.; Narad, M.E.; Kurowski, B.G.; Yeates, K.O.; Taylor, H.G.; Wade, S.L. Examination of Injury, Host, and Social-Environmental Moderators of Online Family Problem Solving Treatment Efficacy for Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury Using an Individual Participant Data Meta-Analytic Approach. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.L.; Narad, M.E.; Shultz, E.L.; Kurowski, B.G.; Miley, A.E.; Aguilar, J.M.; Adlam, A.-L.R. Technology-assisted rehabilitation interventions following pediatric brain injury. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2018, 62, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbarao, B.S.; Stokke, J.; Martin, S.J. Telerehabilitation in Acquired Brain Injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 32, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, S.L.; Raj, S.P.; Moscato, E.L.; Narad, M.E. Clinician perspectives delivering telehealth interventions to children/families impacted by pediatric traumatic brain injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2019, 64, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solana, J.; Caceres, C.; Garcia-Molina, A.; Opisso, E.; Roig, T.; Tormos, J.M.; Gomez, E.J. Improving Brain Injury Cognitive Rehabilitation by Personalized Telerehabilitation Services: Guttmann Neuropersonal Trainer. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2015, 19, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øra, H.P.; Kirmess, M.; Brady, M.C.; Partee, I.; Hognestad, R.B.; Johannessen, B.B.; Thommessen, B.; Becker, F. The effect of augmented speech-language therapy delivered by telerehabilitation on poststroke aphasia—A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, S.A.; Booth, A.T.; Schnabel, A.; Wright, B.J.; Painter, F.L.; McIntosh, J.E. Exploring the Efficacy of Telehealth for Family Therapy Through Systematic, Meta-analytic, and Qualitative Evidence. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.R.; Woodward, E.N.; Drummond, K.L.; Deen, T.L.; Oliver, K.A.; Petersen, N.J.; Meit, S.S.; Fortney, J.C.; Kirchner, J.E. Using implementation facilitation to implement primary care mental health integration via clinical video telehealth in rural clinics: Protocol for a hybrid type 2 cluster randomized stepped-wedge design. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, C.; Oldrati, V.; Oprandi, M.C.; Ferrari, E.; Poggi, G.; Borgatti, R.; Urgesi, C.; Bardoni, A. Remote Technology-Based Training Programs for Children with Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analytic Exploration. Behav. Neurol. 2019, 2019, 1346987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M.; Hawley, C.; Blackwood, B.; Evans, J.; Anderson, V. Technological aids for the rehabilitation of memory and executive functioning in children and adolescents with acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, 11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.; Dunford, C.; Forsyth, R.; Kavcic, A. Using child- and family-centred goal setting as an outcome measure in residential rehabilitation for children and youth with acquired brain injuries: The challenge of predicting expected levels of achievement. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny-Pacini, A.; Hiebel, J.; Pauly, F.; Godon, S.; Chevignard, M. Goal Attainment Scaling in rehabilitation: A literature-based update. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 56, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vroland-Nordstrand, K.; Eliasson, A.-C.; Jacobsson, H.; Johansson, U.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L. Can children identify and achieve goals for intervention? A randomized trial comparing two goal-setting approaches. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, L.; Moriarty, H.J.; Robinson, K.; Piersol, C.; Vause-Earland, T.; Newhart, B.; Iacovone, D.B.; Hodgson, N.; Gitlin, L.N. Efficacy and acceptability of a home-based, family-inclusive intervention for veterans with TBI: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgen, I.M.H.; Løvstad, M.; Andelic, N.; Hauger, S.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Søberg, H.L.; Sveen, U.; Forslund, M.V.; Kleffelgård, I.; Lindstad, M.Ø.; et al. Traumatic brain injury—Needs and treatment options in the chronic phase: Study protocol for a randomized controlled community-based intervention. Trials 2020, 21, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.; Boyd, K.; Craig, N.; French, D.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Cooper, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; et al. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: The need for guidance. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Imms, C.; Stewart, D.; Freeman, M.; Nguyen, T. A transactional framework for pediatric rehabilitation: Shifting the focus to situated contexts, transactional processes, and adaptive developmental outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A.; PAFS Consensus Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th ed.; NCS Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Talley, J.L. Children’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test-2; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Korkman, M.; Kirk, U.; Kemp, S. NEPSY-II, 2nd ed.; Harcourt Assessment: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1999, 40, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedell, G. Further validation of the Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP). Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2009, 12, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayr, L.K.; Yeates, K.O.; Taylor, H.G.; Browne, M. Dimensions of postconcussive symptoms in children with mild traumatic brain injuries. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2009, 15, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.O.; Jones, W.H. The Parental Stress Scale: Initial Psychometric Evidence. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 12, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, S.; Bloomfield, L. Developing and validating a tool to measure parenting self-efficacy. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 51, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wright, F.V. Development of the family needs questionnaire—Pediatric version [FNQ-P]—Phase I. Brain Inj. 2019, 33, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9—Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder—The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, I.M.H.; Hauger, S.L.; Forslund, M.V.; Kleffelgård, I.; Brunborg, C.; Andelic, N.; Sveen, U.; Søberg, H.L.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Røe, C.; et al. Goal Attainment in an Individually Tailored and Home-Based Intervention in the Chronic Phase after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovend’Eerdt, T.J.H.; Botell, R.E.; Wade, D. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: A practical guide. Clin. Rehabil. 2009, 23, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, J.F. Goal Attainment Scaling in Rehabilitation. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 1999, 9, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catroppa, C.; Anderson, V.; Beauchamp, M.; Yeates, K. New Frontiers in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: An Evidence Base for Clinical Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schrieff-Elson, L.E.; Thomas, K.G.F.; Rohlwink, U.K. Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Outcomes and Rehabilitation. In Textbook of Pediatric Neurosurgery; Di Rocco, C., Pang, D., Rutka, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Limond, J.; Leeke, R. Practitioner Review: Cognitive rehabilitation for children with acquired brain injury. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laatsch, L.; Harrington, D.; Hotz, G.; Marcantuono, J.; Mozzoni, M.P.; Walsh, V.; Hersey, K.P. An Evidence-based Review of Cognitive and Behavioral Rehabilitation Treatment Studies in Children with Acquired Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007, 22, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resch, C.; Rosema, S.; Hurks, P.; de Kloet, A.; Van Heugten, C. Searching for effective components of cognitive rehabilitation for children and adolescents with acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlberg, M.M. Cognitive Rehabilitation Manual: Translating Evidence-Based Recommendations into Practice. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2012, 27, 931–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crowe, L.M.; Catroppa, C.; Anderson, V. Sequelae in children: Developmental consequences. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 128, pp. 661–677. [Google Scholar]

- Stallard, N. Optimal sample sizes for phase II clinical trials and pilot studies. Stat. Med. 2012, 31, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingham, S.A.; Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomine, B.S.; McCarthy, M.L.; Ding, R.; MacKenzie, E.J.; Jaffe, K.M.; Aitken, M.E.; Durbin, D.R.; Christensen, J.R.; Dorsch, A.M.; Paidas, C.N.; et al. Health Care Utilization and Needs After Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e663–e674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Wilson, B.A. When implicit learning fails: Amnesia and the problem of error elimination. Neuropsychologia 1994, 32, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiuseppe, R.; Linscott, J.; Jilton, R. Developing the therapeutic alliance in child—Adolescent psychotherapy. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 1996, 5, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjermestad, K. Therapeutic alliance in cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents. Tidsskr. Nor. Psykologforen. 2011, 48, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, B.D.; Weisz, J.R. The Therapy Process Observational Coding System-Alliance Scale: Measure Characteristics and Prediction of Outcome in Usual Clinical Practice. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øra, H.P.; Kirmess, M.; Brady, M.C.; Sørli, H.; Becker, F. Technical Features, Feasibility, and Acceptability of Augmented Telerehabilitation in Post-stroke Aphasia—Experiences from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keck, C.S.; Doarn, C. Telehealth Technology Applications in Speech-Language Pathology. Telemed. e-Health 2014, 20, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, T.N.; Raj, S.P.; Oberjohn, K.S.; Cassedy, A.; Makoroff, K.L.; Fouladi, M.; Wade, S.L. A Pilot Randomized Trial of an Online Parenting Skills Program for Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Improvements in Parenting and Child Behavior. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.L.; Taylor, H.G.; Cassedy, A.; Zhang, N.; Kirkwood, M.W.; Brown, T.M.; Stancin, T. Long-Term Behavioral Outcomes after a Randomized, Clinical Trial of Counselor-Assisted Problem Solving for Adolescents with Complicated Mild-to-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hypher, R.E.; Brandt, A.E.; Risnes, K.; Rø, T.B.; Skovlund, E.; Andersson, S.; Finnanger, T.G.; Stubberud, J. Paediatric goal management training in patients with acquired brain injury: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.L.; Cassedy, A.E.; Shultz, E.L.; Zang, H.; Zhang, N.; Kirkwood, M.W.; Stancin, T.; Yeates, K.; Taylor, H.G. Randomized Clinical Trial of Online Parent Training for Behavior Problems After Early Brain Injury. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 930–939.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer-Baumgartner, N.; Holthe, I.L.; Svendsen, E.J.; Røe, C.; Egeland, J.; Borgen, I.M.H.; Hauger, S.L.; Forslund, M.V.; Brunborg, C.; Prag Øra, H.; et al. Rehabilitation for children with chronic acquired brain injury in the Child in Context Intervention (CICI) study: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2022, 23, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assessment Domain | Instrument |

|---|---|

| Neuropsychological Assessment at Baseline Only | |

| Verbal IQ estimate | Similarities from Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V) [40] |

| Non-verbal IQ estimate | Matrix reasoning from WISC-V |

| Auditory attention/verbal working memory | Digit span from WISC-V |

| Visuomotor processing speed | Coding from WISC-V |

| Verbal learning and memory | Children’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test-2 (CAVLT-2) [41] |

| Verbal inhibition | Inhibition from the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (NEPSY-II) [42] |

| Auditory comprehension | Comprehension of instructions from NEPSY-II |

| Questionnaires at Baseline and Post Intervention | |

| Emotional, behavioral and social functioning | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [43] |

| Participation: home, neighborhood, community | Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP) [44] |

| Quality of life | The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (Peds-QL) [45] |

| Post-concussive symptoms after ABI | Health and Behavior Inventory (HBI) [46] |

| Executive functioning at home and in school | Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-2. ed. (BRIEF-2) [42] |

| Main pABI-related problem areas of daily life | Likert scale from 0 (Not at all difficult) to 4 (Very difficult) |

| Family functioning | Family Assessment Device (FAD) [47] |

| Parent self-perceived stress | Parental Stress Scale (PSS) [48] |

| Parenting self-efficacy | Tool to measure Parenting Self-Efficacy (TOPSE and Teen TOPSE) [49] |

| Unmet healthcare needs of the family | Family Needs Questionnaire Pediatric Version (FNQ-P) [50] |

| Parents’ depression symptoms | Patient Health Questionnaire—9 item (PHQ-9) [51] |

| Parents’ generalized anxiety symptoms | The General Anxiety Disorder—7 item (GAD-7) [52] |

| Acceptability of intervention, self-tailored | Acceptability Scale rated on a Likert scale from 0 (Completely disagree) to 4 (Completely agree) |

| Objective Assessed by | Predefined Criteria |

|---|---|

| Objective 1: Recruitment procedures | |

| Consent rate. | Highly feasible: More than 30% consent rate Moderately feasible: 15–29% consent rate Not feasible: Less than 15% consent rate |

| Duration of recruitment processes. | Highly feasible: Less than 3 h per family spent on recruitment Moderately feasible: Between 3 and 5 h Not feasible: More than 5 h |

| Number of participants excluded at or after the baseline assessment to reach 6 participation families. | Highly feasible: One or no families excluded at or after baseline Moderately feasible: Two families excluded at or after baseline Not feasible: More than two families excluded at or after baseline |

| Drop-out rate. | Highly feasible: No drop-outs Moderately feasible: One drop-out Not feasible: Two or more drop-outs |

| Objective 2: Contents and structure of the intervention | |

| Attendance rate. | Measured in % attendance |

| Feasibility of the SMART-goal approach by feedback from participants on three items on the Acceptability Scale concerning the importance of the goals, and how helpful the strategies were for the child and for the family. | Highly feasible: Median score over 3 (“Agree”) Moderately feasible: Median score between 2 (“Agree moderately”) and 3 (“Agree”) Not feasible: Median score lower than 2 |

| Feasibility of videoconference in treatment delivery as assessed by: | |

| - One question in the Acceptability Scale concerning the quality of communication through videoconference rated by the children, their parents and the therapists. | Highly feasible: Median score over 3 (“Agree”) Moderately feasible: Median score between 2 (“Agree moderately”) and 3 (“Agree”) Not feasible: Median score lower than 2 |

| - A technical log, where number and type of technical failures were reported by the therapists. | Highly feasible: Restart of equipment in 0–1 session per family Moderately feasible: Restart in 2–3 sessions Not feasible: Restart in more than 4 sessions per family |

| Objective 3: Acceptability for the children, parents and therapists | |

| Working alliance in the intervention was measured by child and parent ratings on six items concerning the relation with the therapist; the experience of being heard, taken seriously and given information; and whether they would recommend the study to others. In addition, working alliance was rated by the therapists on five items concerning the experienced quality of relationship with the families. | Highly feasible: Median score over 3 (“Agree”) Moderately feasible: Median score between 2 (“Agree moderately”) and 3 (“Agree”) Not feasible: Median score lower than 2 |

| Usefulness of the intervention was rated on six items on the Acceptability Scale for the children and nine items for the parents, concerning the helpfulness of the intervention, the knowledge transfer to other situations and whether one learned something new. In addition, the therapists rated their experience of the usefulness of the intervention for the families on seven items concerning helpfulness of the intervention, importance of the goals, usefulness of the parent group seminar and awareness of and openness toward the child’s challenges. | Highly feasible: Median score over 3 (“Agree”) Moderately feasible: Median score between 2 (“Agree moderately”) and 3 (“Agree”) Not feasible: Median score lower than 2 |

| Objective 4: Methods of assessment at baseline and T2 | |

| Burden of assessment was rated on the Acceptability Scale by four children, and parents rated items concerning whether the child was comfortable being tested and expressing his/her symptoms and opinions through the questionnaires, understood the questionnaires, and was fatigued by the assessments. Parents also rated two items concerning the number of questionnaires and the relevance of the topics in the questionnaires. | Highly feasible: Median score over 3 (“Agree”) Moderately feasible: Median score between 2 (“Agree moderately”) and 3 (“Agree”) Not feasible: Median score lower than 2 |

| Duration of the baseline assessment. | Highly feasible: Less than 3 h Moderately feasible: 3 to 4 h Not feasible: More than 4 h |

| Objective 5: Quality of treatment delivery | |

| Protocol adherence by study-specific checklists monitoring discrepancies between actual intervention delivery and the CICI manual. | Highly feasible: Less than 15% deviation Moderately feasible: 16–25% deviation Not feasible: More than 25% deviation |

| Family | Neuropsychological Functioning | Parents’ Identified Problem Areas | Child’s Identified Problem Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Within normal range | Fatigue, emotion regulation, study technique | Fatigue, study skills |

| 2 | Impaired memory and verbal reasoning (≤−2 sd). Slightly impaired processing speed, working memory and visual reasoning (≤−1 sd). | Fatigue, cognitive gap to peers, worry for child’s emotional health | Fatigue |

| 3 | Executive dysfunction and impaired processing speed (≤−3 sd), impaired working memory (−2 sd), reduced memory functions and verbal reasoning (≤−1.3 sd). | Social challenges, headache, fatigue | Social challenges, headache |

| 4 | Reduced working memory (−1.3 sd) | Parenting a child with ABI, child’s social insecurity, pain | Pain, sleep, fatigue |

| 5 | Overall, severely reduced neurocognitive functioning with all scores in the impaired range (between −1.3 to −3 sd, with all but 2 tests ≤−2 sd) | Parental exhaustion tied to challenges in getting adequate help for child, child’s social isolation | Losing track in conversations with peers, not able to follow activities and changes in the same tempo as peers |

| 6 | Executive dysfunction (≤−2.3 sd), impaired processing speed (−2 sd) and reduced visual reasoning (−1.3 sd) | Social challenges; physical challenges such as balance, coordination and strength; lack of independence in getting around | Getting around independently |

| Participant | Relevance of SMART-Goals | Helpful Strategies for the Child 1 | Satisfaction with Video-conference in Treatment | Working Alliance | Usefulness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | 4 | - | 3 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Mother | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Father | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Child | 3 | - | 3 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Mother | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Father | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Child | 4 | - | 3 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Mother | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Father | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Child | 2 | - | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Mother | * | * | * | * | * |

| Father | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Child | 4 | - | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Mother | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Father | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Child | 3 | - | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mother | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Father | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holthe, I.L.; Rohrer-Baumgartner, N.; Svendsen, E.J.; Hauger, S.L.; Forslund, M.V.; Borgen, I.M.H.; Øra, H.P.; Kleffelgård, I.; Strand-Saugnes, A.P.; Egeland, J.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Complex Telerehabilitation Intervention for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury: The Child in Context Intervention (CICI). J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092564

Holthe IL, Rohrer-Baumgartner N, Svendsen EJ, Hauger SL, Forslund MV, Borgen IMH, Øra HP, Kleffelgård I, Strand-Saugnes AP, Egeland J, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Complex Telerehabilitation Intervention for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury: The Child in Context Intervention (CICI). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(9):2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092564

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolthe, Ingvil Laberg, Nina Rohrer-Baumgartner, Edel J. Svendsen, Solveig Lægreid Hauger, Marit Vindal Forslund, Ida M. H. Borgen, Hege Prag Øra, Ingerid Kleffelgård, Anine Pernille Strand-Saugnes, Jens Egeland, and et al. 2022. "Feasibility and Acceptability of a Complex Telerehabilitation Intervention for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury: The Child in Context Intervention (CICI)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 9: 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092564

APA StyleHolthe, I. L., Rohrer-Baumgartner, N., Svendsen, E. J., Hauger, S. L., Forslund, M. V., Borgen, I. M. H., Øra, H. P., Kleffelgård, I., Strand-Saugnes, A. P., Egeland, J., Røe, C., Wade, S. L., & Løvstad, M. (2022). Feasibility and Acceptability of a Complex Telerehabilitation Intervention for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury: The Child in Context Intervention (CICI). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(9), 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092564