The Moderating Role of the FKBP5 Gene Polymorphisms in the Relationship between Attachment Style, Perceived Stress and Psychotic-like Experiences in Non-Clinical Young Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Prodromal Questionnaire 16 (PQ-16)

2.2.2. Psychosis Attachment Measure (PAM)

2.2.3. Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10)

2.3. Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

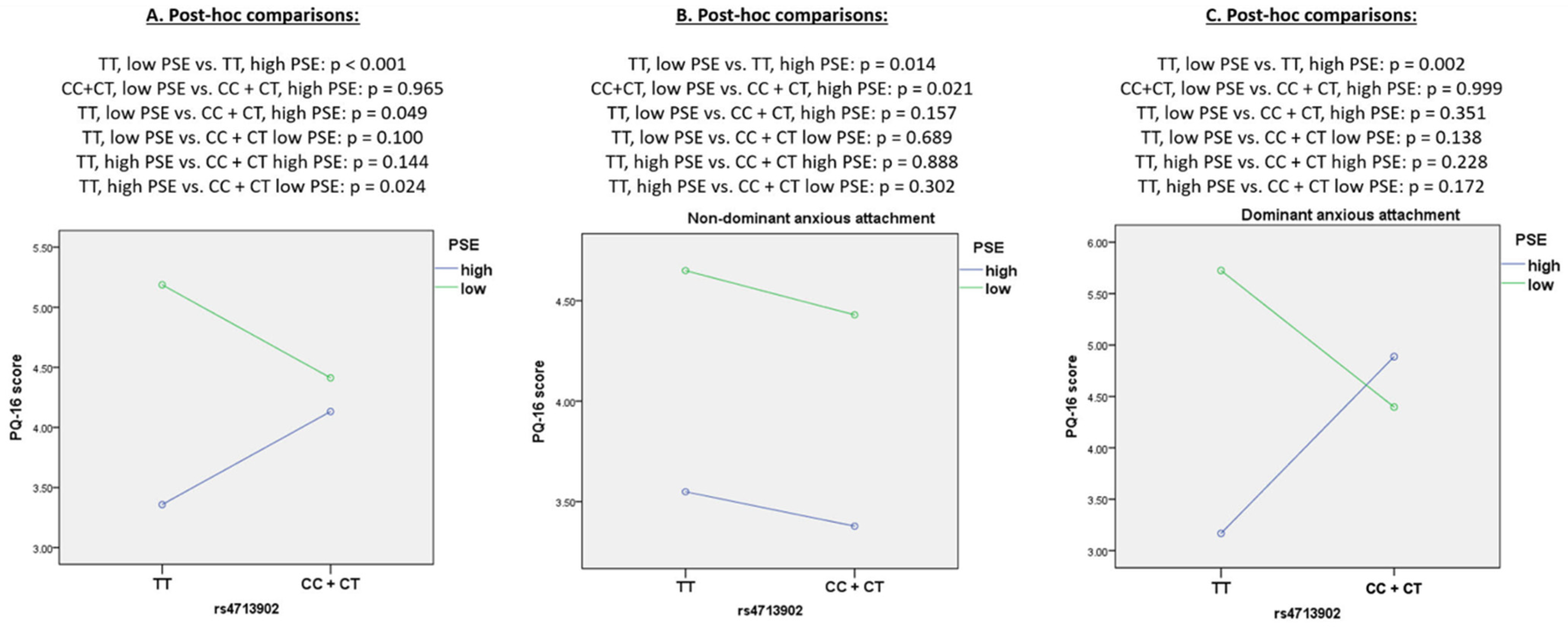

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Os, J.; Kenis, G.; Rutten, B.P.F. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature 2010, 468, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Winkel, R.; Stefanis, N.C.; Myin-Germeys, I. Psychosocial stress and psychosis. A review of the neurobiological mechanisms and the evidence for gene-stress inter- action. Schizophr. Bull. 2008, 34, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Winkel, R.; Van Nierop, M.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Van Os, J. Childhood trauma as a cause of psychosis: Linking genes, psychology, and biology. Can. J. Psychiatry 2013, 58, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Os, J.; Hanssen, M.; Bijl, R.V.; Ravelli, A. Strauss (1969) revisited: A psychosis continuum in the general population? Schizophr. Res. 2000, 45, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linscott, R.J.; van Os, J. An updated and conservative systematic review and meta- analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: On the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 1133–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frydecka, D.; Kotowicz, K.; Gaweda, L.; Prochwicz, K.; Kłosowska, J.; Rymaszewska, J.; Samochowiec, A.; Samochowiec, J.; Podwalski, P.; Pawlak-Adamska, E.; et al. Effects of interactions between variation in dopaminergic genes, traumatic life events, and anomalous self-experiences on psychosis proneness: Results from a cross-sectional study in a nonclinical sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotowicz, K.; Frydecka, D.; Gaweda, L.; Prochwicz, K.; Kłosowska, J.; Rymaszewska, J.; Samochowiec, A.; Samochowiec, J.; Szczygieł, K.; Pawlak-Adamska, E.; et al. Effects of traumatic life events, cognitive biases and variation in dopaminergic genes on psychosis proneness. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frydecka, D.; Misiak, B.; Kotowicz, K.; Pionke, R.; Krężołek, M.; Cechnicki, A.; Gawęda, Ł. The interplay between childhood trauma, cognitive biases, and cannabis use on the risk of psychosis in nonclinical young adults in Poland. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metel, D.; Arciszewska, A.; Daren, A.; Pionke, R.; Cechnicki, A.; Frydecka, D.; Gawęda, Ł. Mediating role of cognitive biases, resilience and depressive symptoms in the relationship between childhood trauma and psychotic-like experiences in young adults. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2020, 14, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pionke-Ubych, R.; Frydecka, D.; Cechnicki, A.; Nelson, B.; Gawęda, Ł. The Indirect Effect of Trauma via Cognitive Biases and Self-Disturbances on Psychotic-Like Experiences. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 611069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaweda, L.; Pionke, R.; Arciszewska, A.; Prochwicz, K.; Frydecka, D.; Misiak, B.; Cechnicki, A.; Cicero, D.C.; Nelson, B. A combination of self-disturbances and psychotic-like experiences. A cluster analysis study on a non-clinical sample in Poland. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawęda, Ł.; Pionke, R.; Krężołek, M.; Prochwicz, K.; Kłosowska, J.; Frydecka, D.; Misiak, B.; Kotowicz, K.; Samochowiec, A.; Mak, M.; et al. Self-disturbances, cognitive biases and insecure attachment as mechanisms of the relationship between traumatic life events and psychotic-like experiences in non-clinical adults—A path analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 259, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.E.; Reeves, L.E.; Cooper, S.; Olino, T.M.; Ellman, L.M. Traumatic life event exposure and psychotic-like experiences: A multiple mediation model of cognitive-based mechanisms. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 205, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaweda, L.; Pionke, R.; Hartmann, J.; Nelson, B.; Cechnicki, A.; Frydecka, D. Toward a Complex Network of Risks for Psychosis: Combining Trauma, Cognitive Biases, Depression, and Psychotic-like Experiences on a Large Sample of Young Adults. Schizophr. Bull. 2021, 47, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaweda, L.; Pionke, R.; Krezolek, M.; Frydecka, D.; Nelson, B.; Cechnicki, A. The interplay between childhood trauma, cognitive biases, psychotic-like experiences and depression and their additive impact on predicting lifetime suicidal behavior in young adults. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristóbal-Narváez, P.; Sheinbaum, T.; Ballespí, S.; Mitjavila, M.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Kwapil, T.R.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Psychotic-Like Symptoms and Stress Reactivity in Daily Life in Nonclinical Young Adults. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ered, A.; Gibson, L.E.; Maxwell, S.D.; Cooper, S.; Ellman, L.M. Coping as a mediator of stress and psychotic-like experiences. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 43, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochwicz, K.; Kłosowska, J.; Dembinska, A. The Mediating Role of Stress in the Relationship Between Attention to Threat Bias and Psychotic-Like Experiences Depends on Coping Strategies. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrak, R.; Güler, M.; Şahin, N.H. The Mediating Role of Self-Concept and Coping Strategies on the Relationship Between Attachment Styles and Perceived Stress. Eur. J. Psychol. 2018, 14, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hawkins, A.C.; Howard, R.A.; Oyebode, J.Y. Stress and coping in hospice nursing staff: The impact of attachment styles. Psycho. Oncol. 2007, 16, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.-H. Relationship among stress coping, secure attachment, and the trait of resilience among Taiwanese college students. Coll. Stud. J. 2008, 42, 312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Pilton, M.; Bucci, S.; McManus, J.; Hayward, M.; Emsley, R.; Berry, K. Does insecure attachment mediate the relationship between trauma and voice-hearing in psychosis? Psychiatry Res. 2016, 246, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheinbaum, T.; Kwapil, T.R.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Fearful attachment mediates the association of childhood trauma with schizotypy and psychotic-like experiences. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheinbaum, T.; Bifulco, A.; Bifulco, A.; Ballespí, S.; Mitjavila, M.; Kwapil, T.R.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Interview investigation of insecure attachment styles as mediators between poor childhood care and schizophrenia-spectrum phenomenology. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sitko, K.; Bentall, R.P.; Shevlin, M.; O’Sullivan, N.; Sellwood, W. Associations between specific psychotic symptoms and specific childhood adversities are mediated by attachment styles: An analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 217, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, D.S.; Korver-Nieberg, N.; Velthorst, E.; Meijer, C.J.; de Haan, L. Childhood maltreatment, adult attachment and psychotic symptomatology: A study in patients, siblings and controls. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, K.; Rush, R.; Grünwald, L.; Darling, S.; Tiliopoulos, N. Attachment as a partial mediator of the relationship between emotional abuse and schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 230, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment: Attachment and Loss, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.; Pereg, D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics and Change; Guilgord Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Patriciello, G.; Ruzzi, V.; Fico, G.; Pellegrino, F.; Castellini, G.; Steardo, L., Jr.; Monteleone, P.; Maj, M. Insecure Attachment and Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Functioning in People with Eating Disorders. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 80, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, C.; Newport, D.J.; Mletzko, T.; Miller, A.H.; Nemeroff, C.B. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2008, 33, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.C.M.; Sharifi, N.; Condren, R.; Thakore, J.H. Evidence of basal pituitary-adrenal overactivity in first episode, drug naïve patients with schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braehler, C.; Holowka, D.; Brunet, A.; Beaulieu, S.; Baptista, T.; Debruille, J.B.; Walker, C.D.; King, S. Diurnal cortisol in schizophrenia patients with childhood trauma. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 79, 353–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; Brennan, P.A.; Esterberg, M.; Brasfield, J.; Pearce, B.; Compton, M.T. Longitudinal changes in cortisol secretion and conversion to psychosis in at-risk youth. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brent, B.K.; Holt, D.J.; Keshavan, M.S.; Seidman, L.J.; Fonagy, P. Mentalization- based treatment for psychosis: Linking an attachment-based model to the psy- chotherapy for impaired mental state understanding in people with psychotic disorders. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2014, 51, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, E.B. The role of FKBP5, a co-chaperone of the glucocorticoid receptor in the pathogenesis and therapy of affective and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34 (Suppl. 1), S186–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramecki, F.; Frydecka, D.; Misiak, B. The role of the interaction between the FKBP5 gene and stressful life events in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: A narrative review. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannas, A.S.; Binder, E.B. Gene-environment interactions at the FKBP5 locus: Sensitive periods, mechanisms and pleiotropism. Genes Brain Behav. 2014, 13, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matosin, N.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Binder, E.B. Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms Underpinning Gene by Environment Interactions in Psychiatric Disorders: The FKBP5 Model. Biological. Psychiatry 2018, 83, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collip, D.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Wichers, M.; Jacobs, N.; Derom, C.; Thiery, E.; Lataster, T.; Simons, C.; Delespaul, P.; Marcelis, M.; et al. FKBP5 as a possible moderator of the psychosis-inducing effects of childhood trauma. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stramecki, F.; Frydecka, D.; Gawęda, Ł.; Prochwicz, K.; Kłosowska, J.; Samochowiec, J.; Szczygieł, K.; Pawlak, E.; Szmida, E.; Skiba, P.; et al. The Impact of the FKBP5 Gene Polymorphisms on the Relationship between Traumatic Life Events and Psychotic-Like Experiences in Non-Clinical Adults. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ising, H.K.; Veling, W.; Loewy, R.L.; Rietveld, M.; Reitdijk, J.; Dragt, S.; Klassen, R.M.C.; Nieman, D.H.; Wunderink, L.; Linszen, D.H.; et al. The validity of the 16-item version of the prodromal questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra-high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, K.; Barrowclough, C.; Wearden, A. Attachment theory: A framework for understanding symptoms and interpersonal relationships in psychosis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpak, M.; Białecka-Pikul, M. Attachment and alexithymia are related, but mind-mindedness does not mediate this relationship. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 46, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P. Childhood attachment and schizophrenia: The “attachment-developmental-cognitive” (ADC) hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses 2014, 83, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Simpson, J.; Berry, K.; Bucci, S.; Moskowitz, A.; Varese, F. Attachment and dissociation as mediators of the link between childhood trauma and psychotic experiences. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.A.; Nitzburg, G.; DeRosse, P.; Karlsgodt, K.H. Relationship between executive function, attachment style, and psychotic like experiences in typically developing youth. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 197, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, D.; Drake, R.; Killackey, E.; Yung, A.R. Perceived stress and psychosis: The effect of perceived stress on psychotic-like experiences in a community sample of adolescents. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mihaljevic, M.; Zeljic, K.; Soldatovic, I.; Andric, S.; Mirjanic, T.; Richards, A.; Mantripragada, K.; Pekmezovic, T.; Novakovic, I.; Maric, N.P. The emerging role of the FKBP5 gene polymorphisms in vulnerability–stress model of schizophrenia: Further evidence from a Serbian population. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 267, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borelli, J.L.; Smiley, P.A.; Rasmussen, H.F.; Gómez, A.; Seaman, L.C.; Nurmi, E.L. Interactive effects of attachment and FKBP5 genotype on school-aged children’s emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Brain Res. 2017, 325 Pt B, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijk, M.P.; Velders, F.P.; Tharner, A.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Hofman, A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Tiemeier, H. FKBP5 and resistant attachment predict cortisol reactivity in infants: Gene-environment interaction. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, R.H.; Rijlaarsdam, J.; Luijk, M.P.; Verhulst, F.C.; Felix, J.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Methylation matters: FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5) methylation moderates the associations of FKBP5 genotype and resistant attachment with stress regulation. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamman, A.J.F.; Sippel, L.M.; Han, S.; Neria, Y.; Krystal, J.H.; Southwick, S.M.; Gelernter, J.; Pietrzak, R.H. Attachment style moderates effects of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse on post-traumatic stress symptoms: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 20, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbané, M.; Salaminios, G.; Luyten, P.; Badoud, D.; Armando, M.; Solida Tozzi, A.; Fonagy, P.; Brent, B.K. Attachment, neurobiology, and mentalizing along the psychosis continuum. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collip, D.; Wigman, J.T.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Jacobs, N.; Derom, C.; Thiery, E.; Wichers, M.; van Os, J. From epidemiology to daily life: Linking daily life stress reactivity to persistence of psychotic experiences in a longitudinal general population study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendler, K.S.; Gallagher, T.J.; Abelson, J.M.; Kessler, R.C. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 23.4 ± 3.0 |

| Gender, M/F | 133/327 (40.7/59.3) |

| Clinical diagnosis | 38 (8.2) |

| Anxious attachment | 1.22 ± 0.65 |

| Avoidant attachment | 1.21 ± 0.65 |

| Predominant anxious attachment | 186 (40.4) |

| Perceived helplessness | 12 ± 5.19 |

| Perceived self-efficacy | 10 ± 2.90 |

| Frequent use of substances (>once per week) | 97 (21.1) |

| PQ-16 | 4.1 ± 4.6 |

| rs1360780 | 450 |

| CC | 260 (58.56) |

| CT | 159 (34.46) |

| TT | 31 (6.98) |

| rs9296158 | 444 |

| AA | 26 (5.84) |

| AG | 159 (35.73) |

| GG | 260 (58.43) |

| rs3800373 | 443 |

| GG | 37 (8.35) |

| TG | 144 (32.51) |

| TT | 262 (59.14) |

| rs9470080 | 443 |

| CC | 245 (55.30) |

| CT | 151 (34.09) |

| TT | 47 (10.61) |

| rs4713902 | 441 |

| CC | 50 (11.34) |

| CT | 154 (34.92) |

| TT | 237 (53.74) |

| rs737054 | 449 |

| CC | 224 (49.89) |

| CT | 182 (40.53) |

| TT | 43 (9.58) |

| Model | Effect | Perceived Helplessness | Perceived Self-Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (exposure) | Perceived stress | F = 43.90, p < 0.001 | F = 25.90, p < 0.001 |

| R2 | 0.088 | 0.054 | |

| Model 2 (exposure and covariates) | Perceived stress | F = 24.62, p < 0.001 | F = 12.90, p < 0.001 |

| Age | F = 39.21, p < 0.001 | F = 42.35, p < 0.001 | |

| Sex | F = 0.68, p = 0.412 | F = 0.60, p = 0.441 | |

| Clinical diagnosis | F = 4.63, p = 0.032 | F = 5.29, p = 0.022 | |

| Frequent substance use | F = 2.09, p = 0.149 | F = 2.92, p = 0.09 | |

| R2 | 0.178 | 0.155 |

| Stress Category | Effect | rs1360780 | rs9296158 | rs3800373 | rs9470080 | rs4713902 | rs737054 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived helplessness | Age | F = 34.11; p < 0.001 | F = 33.28; p < 0.001 | F = 29.09; p < 0.001 | F = 30.96; p < 0.001 | F = 29.61; p < 0.001 | F = 29.83; p < 0.001 |

| Gender | F < 0.01; p = 0.940 | F < 0.01; p = 0.956 | F = 0.02; p = 0.889 | F = 0.01; p = 0.922 | F = 0.01; p = 0.915 | F = 0.03; p = 0.854 | |

| Clinical diagnosis | F = 4.51; p = 0.034 | F = 4.32; p = 0.038 | F = 5.76; p = 0.017 | F = 4.64; p = 0.032 | F = 4.88; p = 0.028 | F = 4.19; p = 0.041 | |

| Frequent substance use | F = 2.85; p = 0.092 | F = 2.90; p = 0.089 | F = 2.21; p = 0.138 | F = 2.05; p = 0.153 | F = 1.28; p = 0.259 | F = 1.93; p = 0.165 | |

| Perceived helplessness | F = 19.68; p < 0.001 | F = 21.62; p < 0.001 | F = 7.00; p = 0.009 | F = 20.53; p < 0.001 | F = 20.70; p < 0.001 | F = 23.14; p < 0.001 | |

| Attachment | F = 3.23; p = 0.073 | F = 3.25; p = 0.072 | F = 0.62; p = 0.433 | F = 3.62; p = 0.058 | F = 2.79; p = 0.096 | F = 2.85; p= 0.092 | |

| FKBP5 | F = 1.11; p = 0.294 | F = 2.36; p = 0.126 | F = 8.82; p = 0.003 | F = 0.81; p = 0.370 | F = 0.10; p = 0.748 | F = 0.16; p = 0.687 | |

| Perceived helplessness × attachment | F = 0.15; p = 0.696 | F = 0.06; p = 0.811 | F = 0.39; p = 0.534 | F = 0.17; p = 0.684 | F = 0.80; p = 0.779 | F = 0.08; p = 0.776 | |

| FKBP5 × attachment | F = 0.23; p = 0.629 | F = 0.06; p = 0.808 | F = 0.03; p = 0.875 | F = 0.12; p = 0.732 | F = 0.25; p = 0.615 | F = 0.52; p = 0.473 | |

| FKBP5 × perceived helplessness | F < 0.01; p = 0.996 | F = 0.06; p = 0.813 | F < 0.01; p = 0.989 | F = 0.23; p = 0.634 | F = 3.49; p = 0.062 | F = 1.66; p = 0.199 | |

| FKBP5 × perceived helplessness × attachment | F = 0.57; p = 0.452 | F = 1.02; p = 0.314 | F = 1.34; p = 0.238 | F = 1.32; p = 0.251 | F = 1.64; p = 0.201 | F = 1.80; p = 0.180 | |

| R2 | 0.189 | 0.192 | 0.207 | 0.182 | 0.184 | 0.192 | |

| Perceived self-efficacy | Age | F = 36.37; p < 0.001 | F = 35.61, p < 0.001 | F = 31.18; p < 0.001 | F = 33.53; p < 0.001 | F = 31.60; p < 0.001 | F = 33.00; p < 0.001 |

| Gender | F < 0.01; p = 0.991 | F < 0.01; p = 0.985 | F < 0.01; p =0.990 | F < 0.01; p = 0.937 | F = 0.00; p = 0.979 | F = 0.02; p = 0.901 | |

| Clinical diagnosis | F = 5.69; p = 0.018 | F = 5.46; p = 0.020 | F = 6.11; p = 0.014 | F = 5.70; p = 0.017 | F = 6.33; p = 0.012 | F = 5.32; p = 0.022 | |

| Frequent substance use | F = 3.71; p = 0.055 | F = 3.59; p = 0.059 | F = 3.28; p = 0.071 | F = 2.75; p = 0.098 | F = 1.97; p = 0.161 | F = 2.84; p = 0.093 | |

| Perceived self-efficacy | F = 10.72; p = 0.001 | F = 11.46; p = 0.001 | F = 4.60; p = 0.033 | F = 11.00; p = 0.001 | F = 12.00; p = 0.001 | F = 11.04; p = 0.001 | |

| Attachment | F = 3.96; p = 0.047 | F = 4.46; p = 0.035 | F = 0.52; p = 0.474 | F = 4.39; p = 0.037 | F = 3.02; p = 0.083 | F = 3.71; p = 0.055 | |

| FKBP5 | F = 0.73; p = 0.394 | F = 1.74; p = 0.188 | F = 8.78; p = 0.003 | F = 0.24; p = 0.626 | F < 0.01; p = 1.000 | F = 0.18; p = 0.668 | |

| Perceived self-efficacy × attachment | F = 0.06; p = 0.803 | F = 0.01; p = 0.920 | F = 0.02; p = 0.884 | F = 0,02; p = 0.882 | F = 0.01; p = 0.945 | F = 0.17; p = 0.678 | |

| FKBP5 × attachment | F = 0.01; p = 0.924 | F = 0.19; p = 0.891 | F = 0.14; p = 0.714 | F = 0.01; p = 0.917 | F = 0.42; p = 0.519 | F = 0.40; p = 0.528 | |

| FKBP5 × perceived self-efficacy | F = 2.53; p = 0.113 | F = 1.93; p = 0.166 | F = 0.09; p = 0.762 | F = 1.14; p = 0.286 | F = 6.64; p = 0.010 | F = 2.44; p = 0.119 | |

| FKBP5 × perceived self-efficacy × attachment | F = 2.14; p = 0.144 | F = 3.17; p = 0.076 | F = 0.06; p = 0.805 | F = 1.57; p = 0.211 | F = 6.18; p = 0.013 | F = 2.18; p = 0.141 | |

| R2 | 0.170 | 0.172 | 0.183 | 0.160 | 0.175 | 0.169 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stramecki, F.; Misiak, B.; Gawęda, Ł.; Prochwicz, K.; Kłosowska, J.; Samochowiec, J.; Samochowiec, A.; Pawlak, E.; Szmida, E.; Skiba, P.; et al. The Moderating Role of the FKBP5 Gene Polymorphisms in the Relationship between Attachment Style, Perceived Stress and Psychotic-like Experiences in Non-Clinical Young Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061614

Stramecki F, Misiak B, Gawęda Ł, Prochwicz K, Kłosowska J, Samochowiec J, Samochowiec A, Pawlak E, Szmida E, Skiba P, et al. The Moderating Role of the FKBP5 Gene Polymorphisms in the Relationship between Attachment Style, Perceived Stress and Psychotic-like Experiences in Non-Clinical Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(6):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061614

Chicago/Turabian StyleStramecki, Filip, Błażej Misiak, Łukasz Gawęda, Katarzyna Prochwicz, Joanna Kłosowska, Jerzy Samochowiec, Agnieszka Samochowiec, Edyta Pawlak, Elżbieta Szmida, Paweł Skiba, and et al. 2022. "The Moderating Role of the FKBP5 Gene Polymorphisms in the Relationship between Attachment Style, Perceived Stress and Psychotic-like Experiences in Non-Clinical Young Adults" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 6: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061614

APA StyleStramecki, F., Misiak, B., Gawęda, Ł., Prochwicz, K., Kłosowska, J., Samochowiec, J., Samochowiec, A., Pawlak, E., Szmida, E., Skiba, P., Cechnicki, A., & Frydecka, D. (2022). The Moderating Role of the FKBP5 Gene Polymorphisms in the Relationship between Attachment Style, Perceived Stress and Psychotic-like Experiences in Non-Clinical Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(6), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061614