Umbilical Endometriosis: A Systematic Literature Review and Pathogenic Theory Proposal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

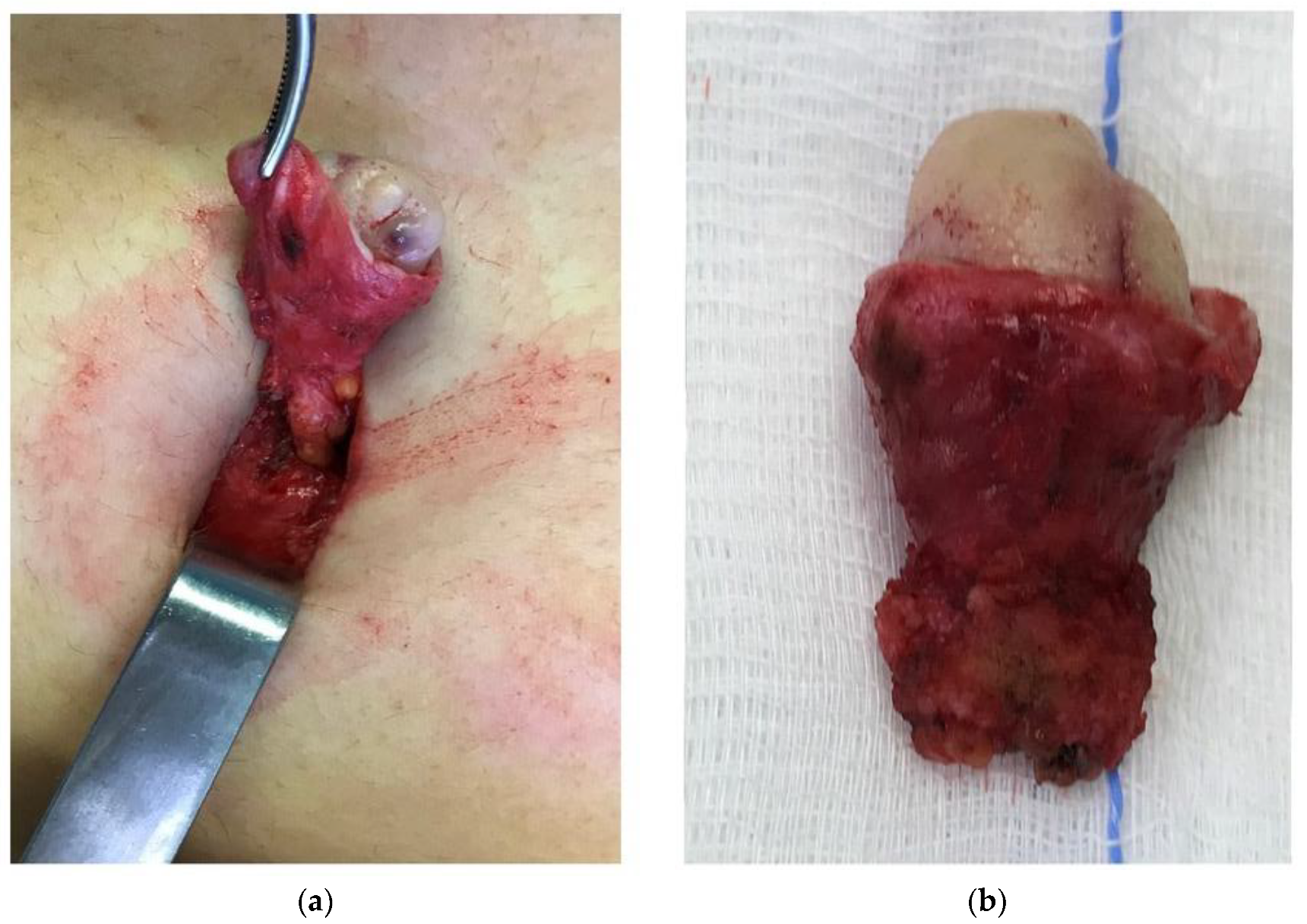

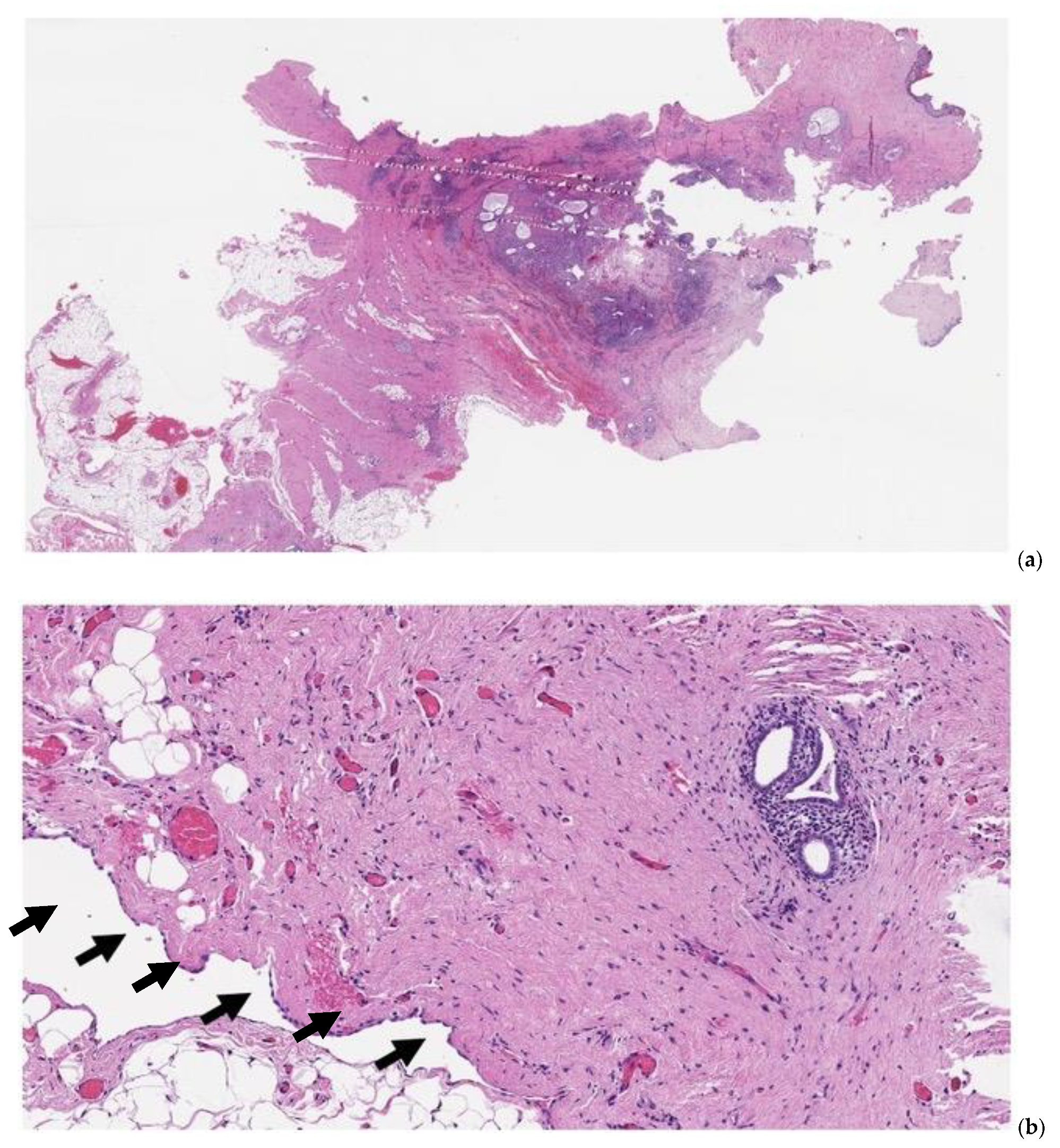

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rowlands, I.J.; Abbott, J.A.; Montgomery, G.W.; Hockey, R.; Rogers, P.; Mishra, G.D. Prevalence and incidence of endometriosis in Australian women: A data linkage cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, J.P.; Yu, O.; Schulze-Rath, R.; Grafton, J.; Hansen, K.; Reed, S.D. Incidence, prevalence, and trends in endometriosis diagnosis: A United States population-based study from 2006 to 2015. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 500.e1–500.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, V.H.; Weil, C.; Chodick, G.; Shalev, V. Epidemiology of endometriosis: A large population-based database study from a healthcare provider with 2 million members. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 125, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gylfason, J.T.; Kristjansson, K.A.; Sverrisdottir, G.; Jonsdottir, K.; Rafnsson, V.; Geirsson, R.T. Pelvic endometriosis diagnosed in an entire nation over 20 years. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calagna, G.; Perino, A.; Chianetta, D.; Vinti, D.; Triolo, M.M.; Rimi, C.; Cucinella, G.; Agrusa, A. Primary umbilical endometrioma: Analyzing the pathogenesis of endometriosis from an unusual localization. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 54, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinella, G.; Granese, R.; Calagna, G.; Candiani, M.; Perino, A. Laparoscopic treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis causing chronic shoulder and arm pain. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2009, 88, 1418.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andres, M.P.; Arcoverde, F.V.L.; Souza, C.C.C.; Fernandes, L.F.C.; Abrao, M.S.; Kho, R.M. Extrapelvic endometriosis: A systematic review. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victory, R.; Diamond, M.P.; Johns, D.A. Villar’s nodule: A case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2007, 14, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Koga, K.; Kitade, M.; Fukuda, S.; Neriishi, K.; Taniguchi, F.; Honda, R.; Takazawa, N.; Tanaka, T.; Kurihara, M.; et al. A national Survey of Umbilical Endometriosis in Japan. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, A.; Dompmartin, A.; Barjot, P.; Louvet, S.; Leroy, D. Umbilical metastasis or Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. Int. J. Dermatol. 1998, 37, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, S.M.; Carpenter, S.E.; Rock, J.A. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 1989, 16, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michowitz, M.; Baratz, M.; Stavorovsky, M. Endometriosis of the umbilicus. Dermatologica 1983, 167, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyamidis, K.; Lora, V.; Kanitakis, J. Spontaneous cutaneous umbilical endometriosis: Report of a new case with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Dermatol. Online J. 2011, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamié, L.P.; Ferreira, R.R.D.M.; Tiferes, D.A.; de Macedo, N.A.C.; Serafini, P.C. Atypical sites of deeply infiltrative endometriosis: Clinical characteristics and imaging findings. Radiographics 2018, 38, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera-Barba, E.; Ramón-Llíon, J.C.; Pérez, A.S.; Navarro, G.I.; Rueda-Pérez, J.M.; Maldonado, A.J.C.; Vazquez-Rojas, L. Endometriosis umbilical primaria. A propósito de 6 casos. Rev. Hispanoam Hernia 2014, 2, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechsner, S.; Bartley, J.; Infanger, M.; Loddenkemper, C.; Herbel, J.; Ebert, A.D. Clinical management and immunohistochemical analysis of umbilical endometriosis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 280, 23542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Koga, K.; Kai, K.; Katabuchi, H.; Kitade, M.; Kitawaki, J.; Kurihara, M.; Takazawa, N.; Tanaka, T.; Taniguchi, F.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of extragenital endometriosis in Japan, 2018. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 2474–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetan, N.; Torkington, J.; Watkin, A.; Jamison, M.H.; Humphreys, W.V. Endometriosis: Presentation to general surgeons. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1999, 81, 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- King, E.S.J. Endometriosis of the umbilicus. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1954, 67, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, A.T. The ultrasound of subcutaneous extrapelvic endometriosis. J. Ultrason. 2020, 20, e176–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marras, S.; Pluchino, N.; Petignat, P.; Wenger, J.M.; Ris, F.; Buchs, N.C.; Dubuisson, J. Abdominal wall endometriosis: An 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2019, 4, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellido-Cotelo, R.; Muñoz-González, J.L.; Oliver-Pérez, M.R.; de la Hera-Lázaro, C.; Almansa-González, C.; Pérez-Sagaseta, C.; Jiménez-López, J.S. Endometriosis node in gynaecologic scars: A study of 17 patients and the diagnostic considerations in clinical experience in tertiary care center. BMC Womens Health 2015, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, A.M.; Donnellan, N.M.; Shepherd, J.P.; Lee, T.T. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 211, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, L.; Manuzzi, L.; Di Donato, N.; Salfi, N.; Trivella, G.; Ceccaroni, M.; Seracchioli, R. Endometriosis of the abdominal wall: Ultrasonographic and doppler characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 39, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, G.K.; Carvalho, L.F.; Korkes, H.; Guazzelli, T.F.; Kenj, G.; Viana Ade, T. Scar endometrioma following obstetric surgical incisions: Retrospective study on 33 cases and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2009, 127, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Fong, Y.F. Cutaneous endometriosis. Singap. Med. J. 2008, 49, 704–709. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lang, J.; Leng, J.; Liu, Z.; Sun, D.; Zhu, L. Abdominal wall endometriomas. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2005, 90, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, P.; Wade-Evans, T. Anterior abdominal wall endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1985, 6, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, W.D.; Helwing, E.B. Coutaneous endometriosis. JAMA 1965, 191, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysostomou, A.; Branch, S.J.; Myamya, N.E. Primary umbilical endometriosis: To scope or not to scope? S. Afr. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 23, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, U.N.; Hayes, J.A. Umbilical endometriosis. Br. J. Clin. Pract. 1968, 22, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lattuneddu, A.; Ercolanni, G.; Orlandi, V.; Saragoni, L.; Garcea, D. Umbilical endometriosis: Description of 3 cases and diagnostic and therapeutic observations. Chirugia. Dec. 2002, 15, 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saad, S.; Al-Shinawi, H.M.; Kumar, M.A.; Brair, A.F.I. Extra-gonadal endometriosis: Unusual presentation. Bahrain Med. Bull. 2007, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dessy, L.A.; Buccheri, E.M.; Chiummariello, S.; Gagliardi, D.N.; Onesti, M.G. Umbilical endometriosis, our experience. In Vivo 2008, 22, 811–815. [Google Scholar]

- Fedele, L.; Frontino, G.; Bianchi, S.; Borruto, F.; Ciappina, N. Umbilical endometriosis: A radical exicision with laparoscopic assistence. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abramowicz, S.; Pura, I.; Vassilieff, M.; Auber, M.; Ness, J.; Denis, M.H.; Marpeau, L.; Roman, H.J. Umbilical endometriosis in women free of abdominal surgical antecedents. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 40, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darouichi, M. Primary and secondary umbilical endometriosis. Feuill. Radiol. 2013, 53, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Koga, K.; Osuga, Y.; Harada, M.; Takemura, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Yano, T.; Kozuma, S. Individualized management of umbilical endometriosis: A report of seven cases. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikazawa, K.; Mitsushita, J.; Netsu, S.; Konno, R. Surgical excision of umbilical endometriotic lesions with laparoscopic pelvic observation is the way to treat umbilical endometriosis. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2014, 7, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boesgaard-Kjer, D.; Boesgaard-Kjer, D.; Kjer, J.J. Primary umbilical endometriosis (PUE). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 209, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, P.V.D.S.; Dos Santos, M.P.; Castro, S.; De Melo, V.A. Primary umbilical endometriosis. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2018, 21, 45, e1746. [Google Scholar]

- Makena, D.; Obura, T.; Mutiso, S.; Oindi, F. Umbilical endometriosis: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 7, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Ochiai, H.; Maeshima, A. Umbilical endometriosis with urachal remnant. Arch. Dermatol. 2012, 148, 1331.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitch, J.; Pines, B.; Grayzel, D.M. Endometriosis of the umbilicus. J. Int. Coll. Surg. 1952, 18, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vercellini, P.; Abbiati, A.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Daguati, R.; Meroni, F.; Crosignani, P.G. Asymmetry in distribution of diaphragmatic endometriotic lesions: Evidence in favour of the menstrual reflux theory. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 2359–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, D.C.; Stern, J.L.; Buscema, J.; Rock, A.; Woodruff, J.D. Pleural and pulmonary endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1981, 58, 552–556. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenshein, N.B.; Leichner, P.K.; Vogelsang, G. Radiocolloids in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1979, 34, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drye, J.C. Intraperitoneal pressure in the human. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1948, 87, 472–475. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, M.A. Distribution of intra-abdominal malignant seeding: Dependency on dynamics of flow of ascitic fluid. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium. Ther. Nucl. Med. 1973, 119, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, M.A. The spread and localization of acute intraperitoneal effusions. Radiology 1970, 95, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, J.S.; Chow, P.K.; Koong, H.N.; Ho, J.M.; Girija, R. Unusual sites (thorax and umbilical hernial sac) of endometriosis. J. R. Coll. Surg. Edinb. 2001, 46, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, A.A. Anatomy and embryology of umbilicus in newborns: A review and clinical correlations. Front. Med. 2016, 10, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, R.; Conte, M.; Egidi, F.; Pietrasanta, D.; Borghese, M. Umbilical metastases: Current viewpoint. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2005, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugen, N.; Kanne, H.; Simmer, F.; van de Water, C.; Voorham, Q.J.; Ho, V.K.; Lemmens, V.E.; Simons, M.; Nagtegaal, I.D. Umbilical metastases: Real-world data shows abysmal outcome. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodheart, R.S.; Cooke, C.T.; Tan, E.; Matz, L.R. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. Med. J. Aust. 1986, 145, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromidou, A.; Machairas, N.; Paspala, A.; Hasemaki, N.; Sotiropoulos, G.C. Diagnosis, surgical treatment and postoperative outcomes of hepatic endometriosis: A systematic review. Ann. Hepatol. 2020, 19, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C.; Lindheim, S.R.; Backhus, L.; Vu, M.; Vang, N.; Nezhat, A.; Nezhat, C. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: A review of diagnosis and management. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2019, 23, e2019.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhat, C.; Seidman, D.S.; Nezhat, F.; Nezhat, C. Laparoscopic surgical. Management of diaphragmatic endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1998, 69, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year of Publication (Ref) | Country | Study Design ° Period of Recruitment °° | Women with Abdominal Wall Endometriosis (n) | Women with UE (n) | Age (Mean) of Women with UE | Primary UE % (n) | Secondary UE % (n) | MINORS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical series | ||||||||

| Steck and Helwing, 1965 [31] | USA | Retrospective study on recorded cases | 70 | 28 | NR | 75.0 (21/28) | 25.0 (7/28) | 8 |

| McKenna and Wade-Evans, 1985 [30] | UK | Retrospective study on recorded cases between 1951–1980 | 25 | 5 | 47.5 | 100 (5/5) | 0 | 8 |

| Zhao et al., 2005 [29] | China | Retrospective study on recorded cases between 1951–1980 | 62 | 2 | NR | 100 (2/2) | 0 | 10 |

| Agarwal et al., 2008 [28] | Singapore | Retrospective study on recorded cases between 2000–2007 | 8 | 2 | 42 | 50.0 (1/2) | 50.0 (1/2) | 9 |

| Leite et al., 2009 [27] | Brazil | Retrospective study 2001–2007 | 31 | 2 | NR | 0 | 100 (2/2) | 10 |

| Savelli et al., 2012 [26] | Italy | Retrospective study 2001–2007 | 19 | 8 | NR | 25.0 (2/8) | 75.0 (6/8) | 8 |

| Ecker et al., 2014 [25] | USA | Retrospective study 2001–2013 | 63 | 9 | NR | 44.4 (4/9) | 55.6 (5/9) | 8 |

| Vellido-Cotelo et al., 2015 [24] | Spain | Retrospective study 2000–2012 | 15 | 2 | 37 | 0 | 100 (2/2) | 8 |

| Chrysostomou et al., 2017 [32] | South Africa | Prospective study 2010–2016 | 14 | 6 | 31.1 | 100 (6/6) | 0 | 13 |

| Marras et al., 2019 [23] | Switzerland | Retrospective study 2007–2017 | 35 | 10 | NR | 60.0 (6/10) | 40.0 (4/10) | 11 |

| Youssef, 2020 [22] | Egypt | Retrospective study 2016–2019 | 21 | 2 | NR | 50.0 (1/2) | 50.0 (1/2) § | 9 |

| Total clinical series | 363 | 76 | 63.2 (48/76) | 36.8 (28/76) | ||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | 51.9–73.1 | 26.9–48.1 | ||||||

| Case series | ||||||||

| Rabinovitch et al., 1952 [46] | USA | NR | 3 | 36 | 100 (3/3) | 0 | 6 | |

| Pathak and Hayes, 1968 [33] | Jamaica | NR | 3 | 42 | 66.7 (2/3) | 33.3 (1/3) | 10 | |

| Lattuneddu et al., 2002 [34] | Italy | 2000–2001 | 3 | 43.6 | 33.3 (1/3) | 66.7 (2/3) | 9 | |

| Al-Saad et al., 2007 [35] | Kingdom of Bahrain | 2002–2005 | 3 | 42.3 | 100 (3/3) | 0 | 11 | |

| Dessy et al., 2008 [36] | Italy | 2003–2006 | 4 | 37 | 50.0 (2/4) | 50.0 (2/4) | 11 | |

| Fedele et al., 2010 [37] | Italy | 2001–2003 | 7 | 37 | 57.1 (4/7) | 42.9 (3/7) | 9 | |

| Abramowicz et al., 2011 [38] | France | NR | 3 | 29 | 100 (3/3) | 0 | 9 | |

| Darouichi et al., 2013 [39] | Switzerland | NR | 3 | 37.3 | 66.7 (2/3) | 33.3 (1/3) | 7 | |

| Saito et al., 2013 [40] | Japan | 1999–2011 | 7 | 35.7 | 71.4 (5/7) | 28.6 (2/7) | 11 | |

| Chikazawa et al., 2014 [41] | Japan | NR | 3 | 37 | 33.3 (1/3) | 66.7 (2/3) | 7 | |

| Boesgaard-Kjer et al., 2017 [42] | Denmark | 2011–2014 | 10 | 28.5 | 100 (10/10) | 0 | 9 | |

| Dos Santos Filho et al., 2018 [43] | Brazil | 2014–2017 | 6 | 33 | 100 (6/6) | 0 | 11 | |

| Hirata et al., 2020 [9] | Japan | 2006–2016 | 96 | 40 | 66.7 (64/96) * | 32.3 (31/96) * | 11 | |

| Makena et al., 2020 [44] | Kenya | 2015–2019 | 5 | 40 | 80.0 (4/5) | 20.0 (1/5) | 10 | |

| Total case series | 156 | 71.0 (110/155) | 29.0 (45/155) | |||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | 63.4–77.5 | 22.5–36.6 | ||||||

| Total all studies | 232 | 68.4 (158/231) | 31.6 (73/231) | |||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | 62.1–74.1 | 26.0–37.9 |

| Author, Year of Publication (Ref) | Parous (Parae/Total Women with UE) % (n) | Cesarean Section (Women with a History of CS/Total Parae) % (n) | Previous Abdominal Surgery (Women with Previous Abdominal Surgery/Total Cases with UE) % (n) | History of Endometriosis (Women with History of Endometriosis/Total Cases UE) % (n) | If Laparoscopy Associated, Concomitant Endometriosis % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical series | |||||

| Steck and Helwing, 1965 [31] | NR | NR | 25.0 (7/28) | NR | NR |

| McKenna and Wade-Evans, 1985 [30] | 100 (5/5) | 0 | 0 | 40.0 (2/5) | 20.0 (1/5) |

| Zhao et al., 2005 [29] | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Agarwal et al., 2008 [28] | 100 (2/2) | 50.0 (1/2) | 50.0 (1/2) | 0 | 50.0 (1/2) |

| Leite et al., 2009 [27] | 100 (2/2) | 100 (2/2) | 100 (2/2) | NR | NR |

| Savelli et al., 2012 [26] | NR | NR | 75.0 (6/8) | 75.0 (6/8) | NR |

| Ecker et al., 2014 [25] | 33.3 (3/9) | 33.3 (1/3) | 55.5 (5/9) | NR | NR |

| Vellido-Cotelo et al., 2015 [24] | 50.0 (1/2) | 100 (1/1) | 100 (2/2) | 50 (1/2) | NR |

| Chrysostomou et al., 2017 [32] | NR | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marras et al., 2019 [23] | NR | NR | 40.0 (4/10) | 60.0 (6/10) | 80.0 (8/10) |

| Youssef, 2020 [22] | NR | NR | 50.0 (1/2) | NR | 50.0 (1/2) |

| Total clinical series | 65.0 (13/20) | 38.5 (5/13) | 36.8 (28/76) | 45.5 (15/33) | 44.0 (11/25) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 43.3–81.9 | 17.7–64.5 | 26.9–48.1 | 29.8–62.0 | 26.7–62.9 |

| Case series | |||||

| Rabinovitch et al., 1952 [46] | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Pathak and Hayes, 1968 [33] | 0 | 0 | 33.3 (1/3) | NR | 33.3 (1/3) § |

| Lattuneddu et al., 2002 [34] | 33.3 (1/3) | 100 (1/1) | 33.3 (1/3) | NR | 33.3 (1/3) |

| Al-Saad et al., 2007 [35] | 66.7 (2/3) | 0 | 0 | NR | NR |

| Dessy et al., 2008 [36] | 75.0 (3/4) | 66.7 (2/3) | 50.0 (2/4) | 0 | NR |

| Fedele et al., 2010 [37] | 14.3 (1/7) | NR | 42.8 (3/7) | 71.4 (5/7) | 28.6 (2/7) |

| Abramowicz et al., 2011 [38] | NR | NR | 0 | 100 (3/3) | 100 (3/3) |

| Darouichi et al., 2013 [39] | 66.7 (2/3) | 50.0 (1/2) | 33.3 (1/3) | 33.3 (1/3) | 33.3 (1/3) |

| Saito et al., 2013 [40] | 28.6 (2/7) | NR | 28.6 (2/7) | 14.3 (1/7) | 14.3 (1/7) |

| Chikazawa et al., 2014 [41] | 100 (3/3) | 66.7 (2/3) | 66.7 (2/3) | 0 | 33.3 (1/3) |

| Boesgaard-Kjer et al., 2017 [42] | 20.0 (2/10) | 0 | 0 | NR | 10.0 (1/10) |

| Dos Santos Filho et al., 2018 [43] | 100 (6/6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR |

| Hirata et al., 2020 [9] | 63.5 (61/96) | 18.0 (11/61) | 32.3 (31/96) ° | NR | NR |

| Makena et al., 2020 [44] | 60.0 (3/5) | 33.3 (1/3) | 20.0 (1/5) | NR | 40.0 (2/5) |

| Total case series | 57.3 (86/150) | 22.2 (18/81) | 28.2 (44/156) | 30.3 (10/33) | 29.5 (13/44) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 49.3–65.0 | 14.5–32.4 | 21.7–35.7 | 17.4–47.3 | 18.2–44.2 |

| Total all studies | 58.2 (99/170) | 24.5 (23/94) | 31.0 (72/232) | 37.9 (25/66) | 34.8 (24/69) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 50.7–65.4 | 16.9–34.1 | 25.4–37.3 | 27.2–49.9 | 24.6–46.6 |

| Author, Year of Publication (Ref) | Pain % (n) | Bleeding % (n) | Catamenial Symptoms * % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical series | |||

| Steck and Helwing, 1965 [31] | NR | NR | NR |

| McKenna and Wade-Evans, 1985 [30] | NR | NR | 80.0 (4/5) |

| Zhao et al., 2005 [29] | NR | NR | NR |

| Agarwal et al., 2008 [28] | 50.0 (1/2) | 100 (2/2) | 100 (1/2) |

| Leite et al., 2009 [27] | NR | 50.0 (1/2) | NR |

| Savelli et al., 2012 [26] | NR | NR | NR |

| Ecker et al., 2014 [25] | 55.5 (5/9) | NR | NR |

| Vellido-Cotelo et al., 2015 [24] | NR | NR | 100 (2/2) |

| Chrysostomou et al., 2017 [32] | 100 (6/6) | 50.0 (3/6) | 0 |

| Marras et al., 2019 [23] | NR | 40.0 (4/10) | NR |

| Youssef, 2020 [22] | 100 (2/2) | 50.0 (1/2) | 100 (2/2) |

| Total clinical series | 73.7 (14/19) | 50.0 (11/22) | 52.9 (9/17) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 51.2–88.2 | 30.7–69.3 | 31.0–73.8 |

| Case series | |||

| Rabinovitch et al., 1952 [46] | 100 (3/3) | 0 (0/3) | 100 (3/3) |

| Pathak and Hayes, 1968 [33] | 100 (3/3) | 0 (0/3) | 66.6 (2/3) |

| Lattuneddu et al., 2002 [34] | 100 (3/3) | NR | NR |

| Al-Saad et al., 2007 [35] | 100 (3/3) | 100 (3/3) | 100 (3/3) |

| Dessy et al., 2008 [36] | 50.0 (2/4) | 25.0 (1/4) | 100 (4/4) |

| Fedele et al., 2010 [37] | 100 (7/7) | 57.0 (4/7) | 100 (7/7) |

| Abramowicz et al., 2011 [38] | 66.6 (2/3) | 33.3 (1/3) | 66.6 (2/3) |

| Darouichi et al., 2013 [39] | 66.6 (2/3) | 33.3 (1/3) | 33.3 (1/3) |

| Saito et al., 2013 [40] | 100 (7/7) | 57.0 (4/7) | 86.0 (6/7) |

| Chikazawa et al., 2014 [41] | 100 (3/3) | 0 (0/3) | 33.3 (1/3) |

| Boesgaard-Kjer et al., 2017 [42] | NR | 100 (10/10) | 100 (10/10) |

| Dos Santos Filho et al., 2018 [43] | 100 (6/6) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (6/6) |

| Hirata et al., 2020 [9] | 81.0 (78/96) | 44.8 (43/96) | 86.5 (83/96) |

| Makena et al., 2020 [44] | 80.0 (4/5) | 100 (5/5) | 100 (5/5) |

| Total case series | 84.2 (123/146) | 51.0 (78/153) | 86.9 (133/153) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 77.5–89.3 | 43.1–58.8 | 80.7–91.4 |

| Total all studies | 83.0 (137/165) | 50.9 (89/175) | 83.5 (142/170) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | 76.6–88.0 | 43.5–58.2 | 77.2–88.4 |

| Author, Year of Publication (Ref) | Cases of UE (n) | Treatment | Duration of Follow Up (Mean in Months and Range) | Recurrence % (n) | Time to Recurrence (Mean in Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical series | |||||

| Agarwal et al., 2008 [28] | 2 | surgery | 20.5 | 0 | |

| Leite et al., 2009 [27] | 2 | surgery | NR | 100 (2/2) | NR |

| Chrysostomou et al., 2017 [32] | 6 | surgery | 36 (6–72) | 0 | |

| Marras et al., 2019 [23] | 10 | surgery | 62.4 ± 39.6 § | 10.0(1/10) | 24 |

| Case series | |||||

| Pathak and Hayes, 1968 [33] | 3 | surgery | 24 (2 cases) NR (1 case) | 33.3 (1/3) | 22 |

| Lattuneddu et al., 2002 [34] | 3 | surgery | 24 | 0 | |

| Al-Saad et al., 2007 [35] | 3 | surgery | 28 | 0 | |

| Dessy et al., 2008 [36] | 4 | surgery | 13 | 0 | |

| Fedele et al., 2010 [37] | 7 | surgery | 92.5 | 0 | |

| Abramowicz et al., 2011 [38] | 3 | surgery | 3 | 0 | |

| Saito et al., 2013 [40] | 7 | 1 surgery ** | 58.3 | 0 | |

| Dos Santos Filho et al., 2018 [43] | 6 | surgery | NR | 0 | |

| Hirata et al., 2020 [9] | 87 * | surgery | 6870 | 3.4 (3/87) | Recurrence occurred in 3 women, at 3, 8, and 12 months after excision without peritoneum. ° |

| Makena et al., 2020 [44] | 5 | surgery | NR | 0 | |

| Total | 148 | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dridi, D.; Chiaffarino, F.; Parazzini, F.; Donati, A.; Buggio, L.; Brambilla, M.; Croci, G.A.; Vercellini, P. Umbilical Endometriosis: A Systematic Literature Review and Pathogenic Theory Proposal. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11040995

Dridi D, Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, Donati A, Buggio L, Brambilla M, Croci GA, Vercellini P. Umbilical Endometriosis: A Systematic Literature Review and Pathogenic Theory Proposal. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(4):995. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11040995

Chicago/Turabian StyleDridi, Dhouha, Francesca Chiaffarino, Fabio Parazzini, Agnese Donati, Laura Buggio, Massimiliano Brambilla, Giorgio Alberto Croci, and Paolo Vercellini. 2022. "Umbilical Endometriosis: A Systematic Literature Review and Pathogenic Theory Proposal" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 4: 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11040995

APA StyleDridi, D., Chiaffarino, F., Parazzini, F., Donati, A., Buggio, L., Brambilla, M., Croci, G. A., & Vercellini, P. (2022). Umbilical Endometriosis: A Systematic Literature Review and Pathogenic Theory Proposal. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(4), 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11040995