Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) as a Promising Treatment for Craving in Stimulant Drugs and Behavioral Addiction: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

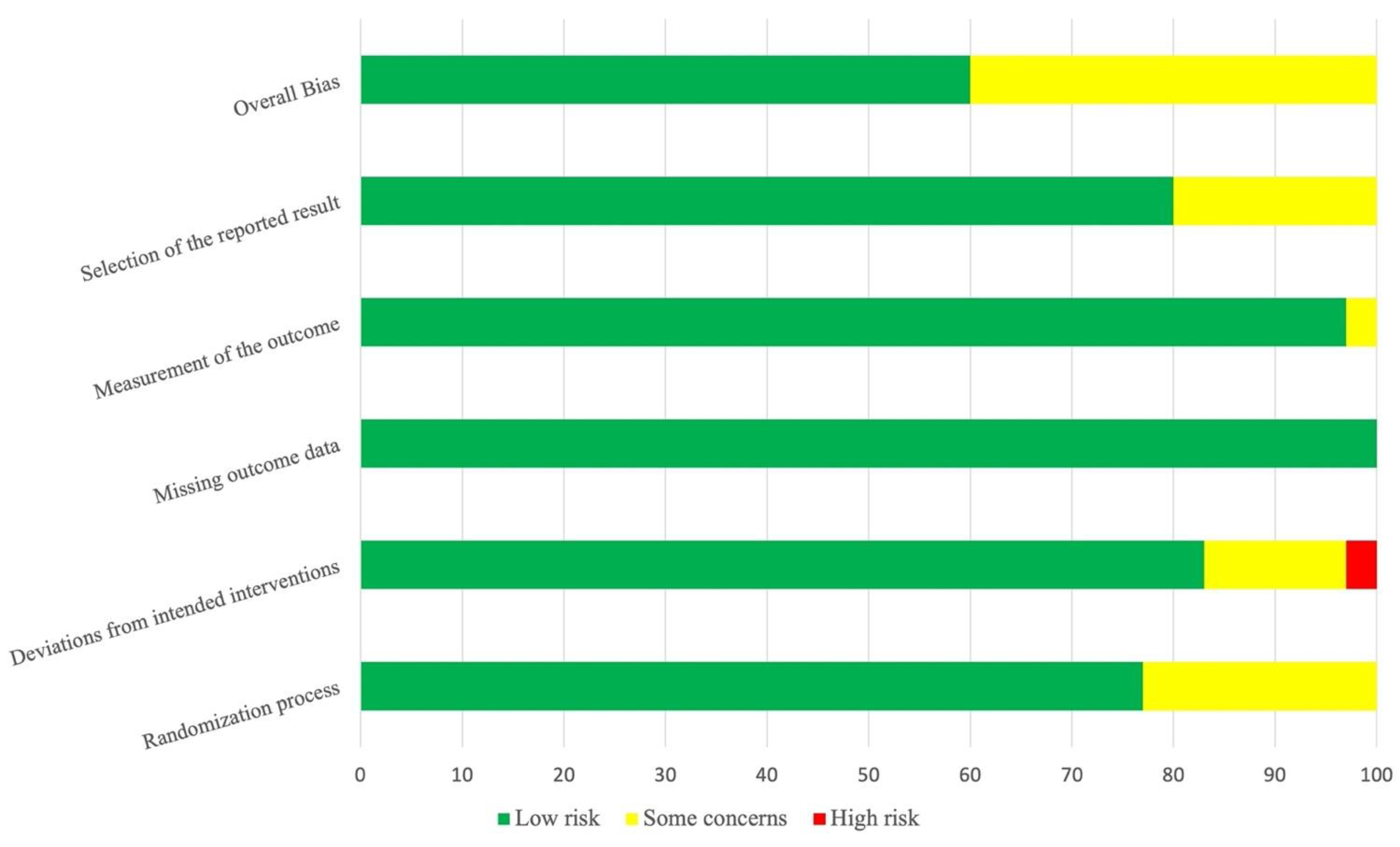

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria for the Selection of Studies

2.3. Study Selection and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

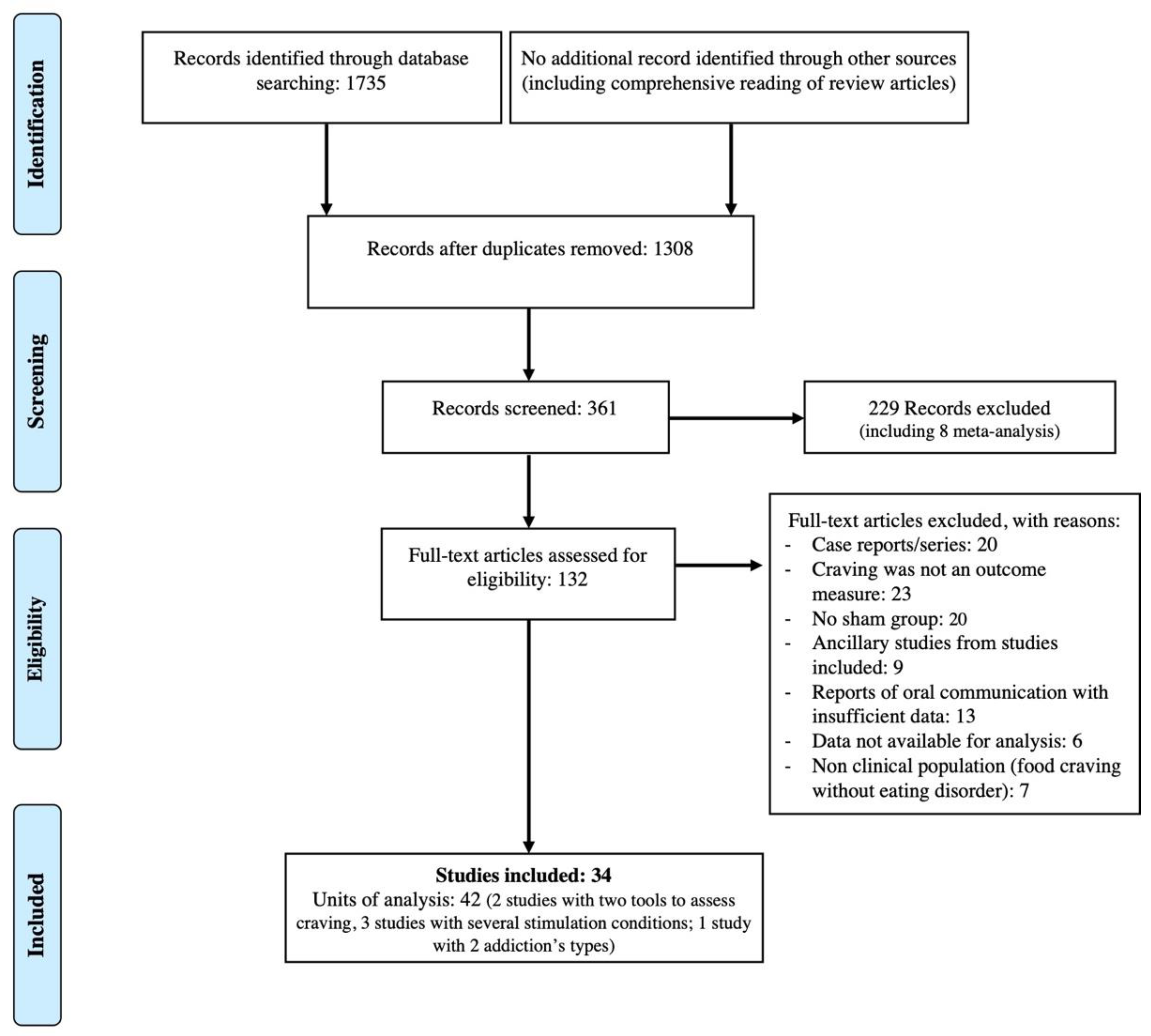

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Main Results

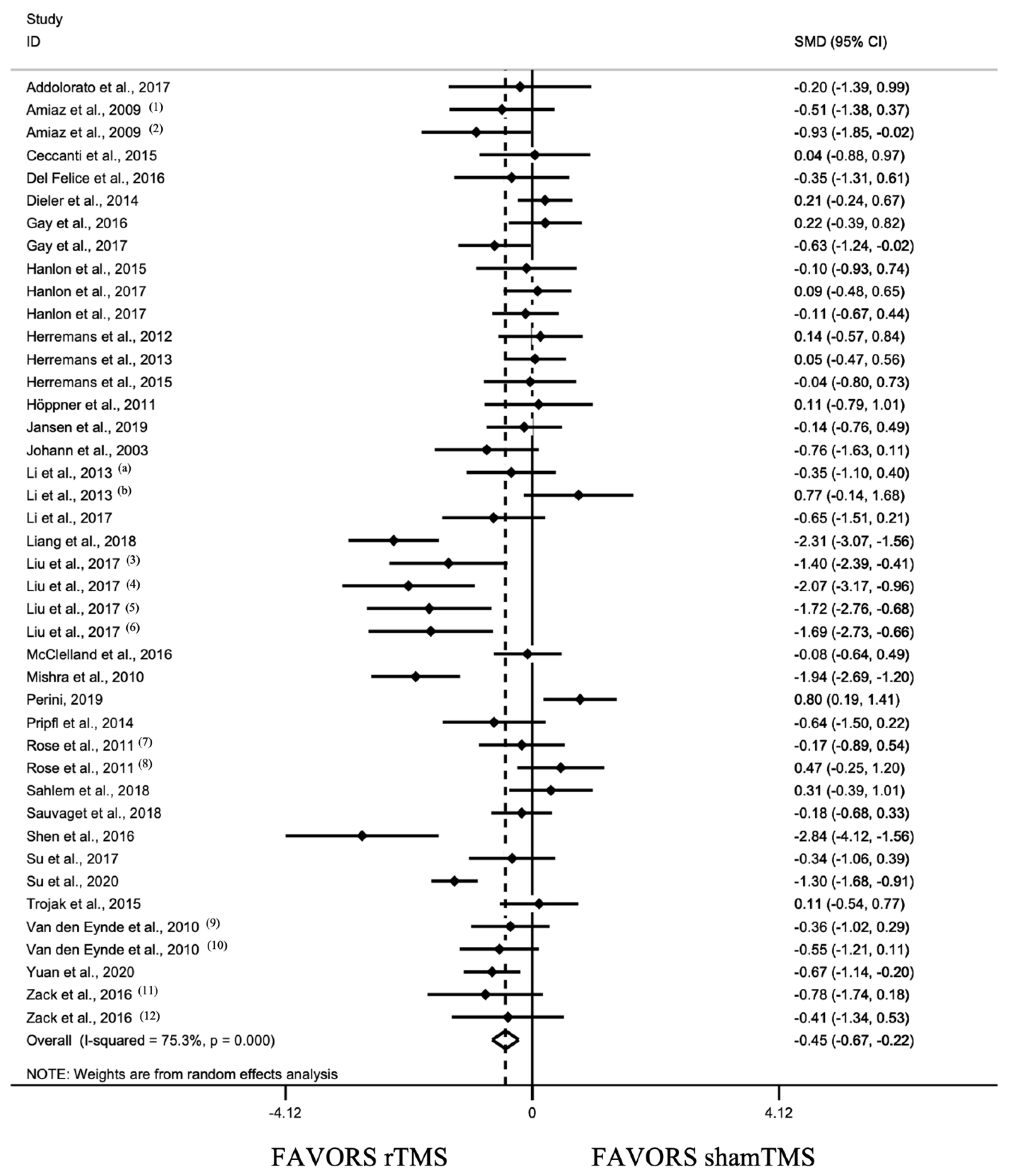

3.2.1. Overall Effect of rTMS and Sensitivity Analysis

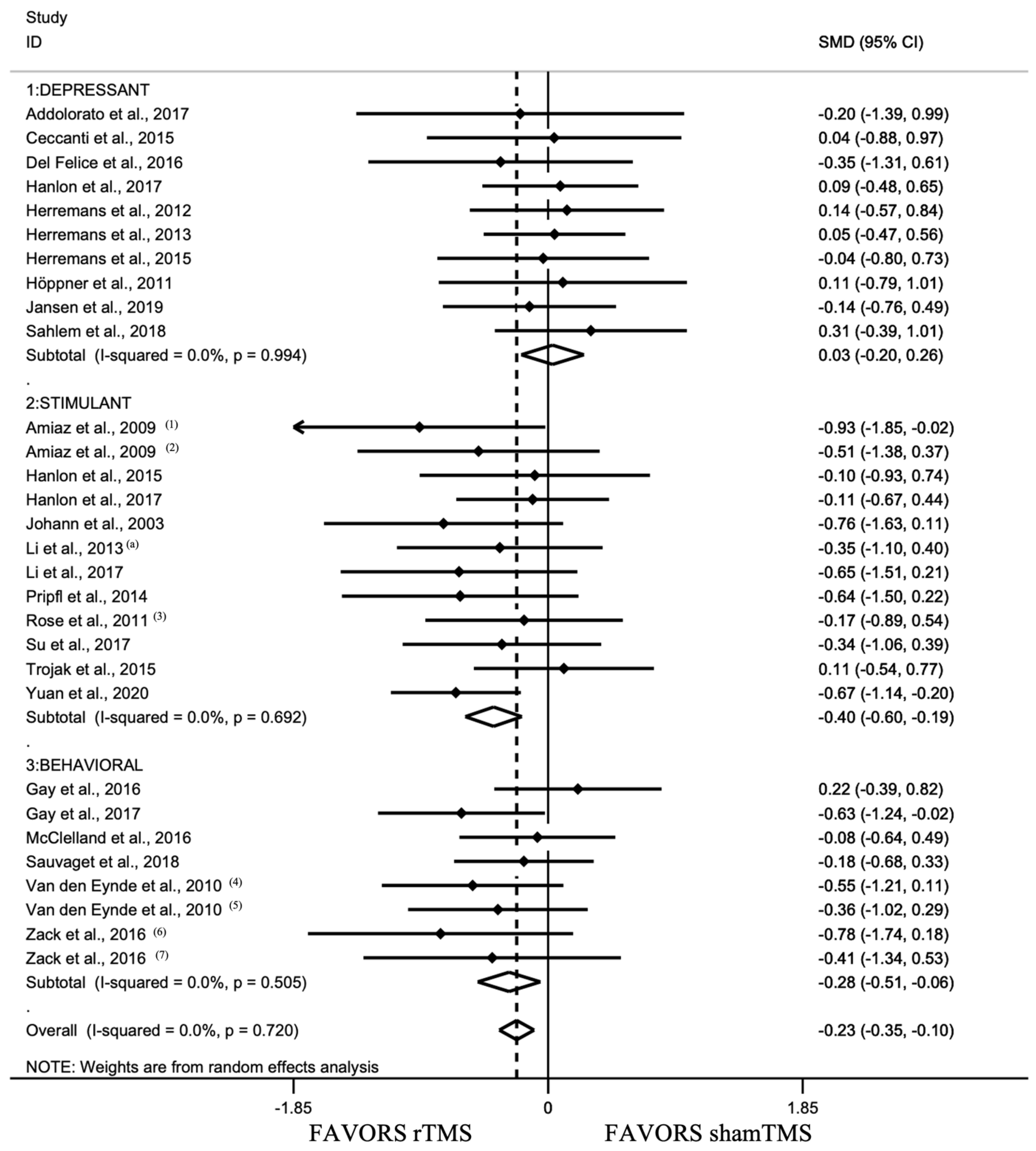

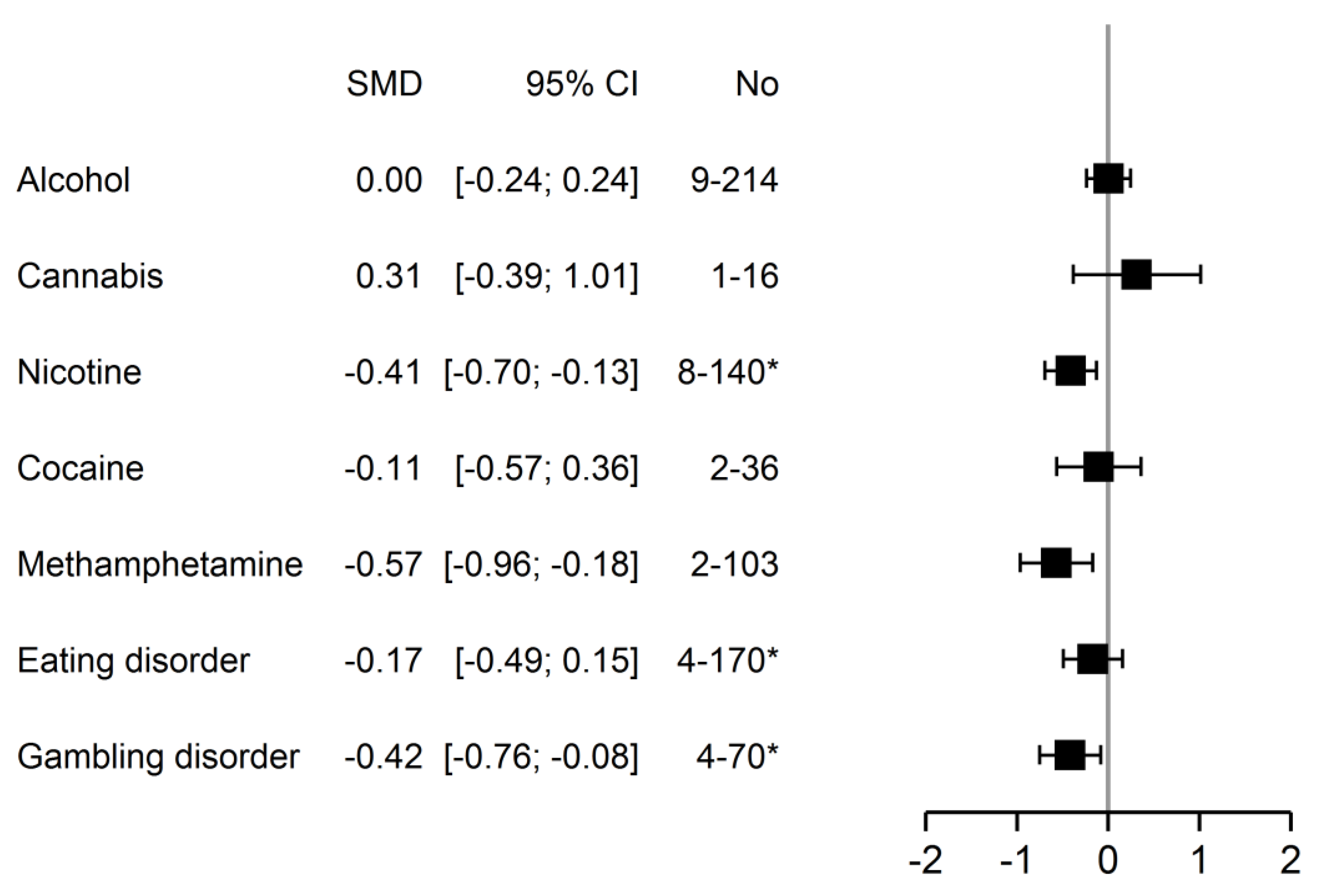

3.2.2. Analyses between Addiction Type Groups

3.3. Analysis of Stimulation Settings

3.4. Safety

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Studies | Design | Population | Stimulation Settings | Method of Craving Assessment and Other Outcome Measures 2 * Craving as Primary Outcome | Main Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Sessions 1 Total Pulses/Session | Frequency (Hz) Intensity (% of RMT) | Stimulation Site Method for Locating Target | Coil Type of shamTMS | |||||

| Depressant group | ||||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||||

| Mishra et al., 2010 [106] | RCT, SB | 45 M, 30 real/15 shamTMS, detoxified | 10 1000 | 10 Hz 110% | R DLPFC NS | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | ACQ-NOW *, before, after, and 1 month after last session | Significant post-rTMS reduction |

| Höppner et al., 2011 [81] | RCT, SB | 19 F, 10 real/9 shamTMS, detoxified | 10 1000 | 20 Hz 90% | L DLPFC 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 45° angulation and shifting | OCDS * Mood (HDRS, BDI) Attentional blink | No significant effect on craving and mood |

| Herremans et al., 2012 [99] | RCT, SB, | 31 inpatients (36 included), 15 real/16 shamTMS, 21 M/10 F, detoxified | 1 1560 | 20 Hz 110% | R DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | OCDS * Before, after, and the 3 days following rTMS in natural setting | No significant effect on craving (immediate or delayed) |

| Herremans et al., 2013 [100] | RCT, SB, crossover, 1 week washout | 29 inpatients (50 included), 19 M/10 F, detoxified | 1 1560 | 20 Hz 110% | R DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | OCDS Go/NoGo test | No significant effect on craving Effect on IIRTV on Go/NoGo |

| Herremans et al., 2015 [101] | Phase 1: RCT, DB, 1 session Phase 2: NC | 26 (Phase 2: 23), 13 real/13 shamTMS, 17 M/9 F, detoxified | Phase 1: 1 Phase 2: 15, for 4 days 1560 | 20 Hz 110% | R DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | Craving cue-induced: TLS *, before rTMS, day1 and 7 General craving: AUQ and OCDS, before rTMS, day 7 fMRI, before rTMS, day1 and 7 | No significant effect on cue-induced craving Significant reduction in general craving after phase 2 |

| Ceccanti et al., 2015 [92] dTMS | RCT, DB | 18 M, 9 real/9 shamTMS, detoxified for 10 days | 10 1500 | 20 Hz 120% | MPFC 5 cm | H coil ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced) Alcohol consumption, cortisolemia, and prolactinemia Before, after rTMS and each month to 6 months | Significant reduction in craving (maintained at 1 month), alcohol consumption, cortisolemia, and prolactinemia |

| Del Felice et al., 2016 [94] | RCT, SB | 17 inpatients (20 included), 8 real/9 shamTMS, 13 M/4 F During detoxification | 4 (2/week, 2 weeks) 1000 | 10 Hz 100% | L DLPFC 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS: wooden panel under coil | VAS Alcohol intake, EEG, Stroop, and Go/NoGo tasks Before and after rTMS sessions, at 1 month | No effect on craving and alcohol intake Significant reduction in fast EEG frequencies Effect on Stroop and Go/NoGo |

| Addolorato et al., 2017 [91] dTMS | RCT, DB | 11, 5 real/6 shamTMS (12 M/2 F included) | 12 (3/week, 4 weeks) 1000 | 10 Hz 100% | Bilat DLPFC 5.5 cm | H coil ShamTMS: blank session | OCDS DAT by SPECT TLFB, STAI, Zung self-rating depression scale | No effect on craving Decrease in DAT availability and alcohol intake, effect on STAI state |

| Hanlon et al., 2017 ** [98] | RCT, SB, crossover, 7–14 days washout | 24 non-treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent, 17 M/7 F | 1 3600 | cTBS 110% | L FP 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced) fMRI before and after cTBS (change in MPFC–striatal connectivity) | No effect on craving Decreased evoked BOLD signal in left OFC, insula, and lateral sensorimotor cortex |

| Jansen et al., 2019 [82] | CT, SB | 39, 19 real/20 shamTMS, 26 M/13 F, Subjects sober for at least 3 weeks 36 HC | 1 3000 | 10 Hz 110% | R DLPFC Neuronavigation guided by fMRI | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | AUQ before and after the emotional reappraisal task, after rTMS Emotion regulation and related brain activity using fMRI | No effect on craving In AUD patients: reduced self-reported emotions to positive and negative images, reduced right DLPFC activity but no significant effect of rTMS on reappraisal-related brain function |

| Perini et al., 2019 [86] dTMS | RCT, DB | 56 (45 finished sessions), 29 real/27 shamTMS (23/22 finished), treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent patients | 15 (5/week, 3 weeks) 1500 | 10 Hz 120% | Insula bilat and overlaying areas excluding ant PFC | H coil, H8 ShamTMS coil | AUQ cue-induced before each session; PACS during rTMS and follow-up (week 1, 2, 4, 8, 12) Consumption during rTMS, at the end of sessions and during follow-up; CGI and CRPS-SA during rTMS follow-up Structural and rsMRI before and after rTMS sessions | Decrease in craving and drinking measures but with no difference between real and shamTMS rTMS Difference in rs insula connectivity after treatment between real and shamTMS groups |

| Cannabis | ||||||||

| Sahlem et al., 2018 [107] | RCT, DB, crossover, 1 week washout | 16 (2 subjects withdrew before first session), 13 M/3 F | 1 4000 | 10 Hz 110% | L DLPFC Beam F3 method | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | MCQ (cue-induced) prior, during, after, and 15 min after the completion of rTMS | No effect on craving Feasibility and safety validated |

| Opiate | ||||||||

| Shen et al., 2016 [108] | RCT | 20 M, 10 real/10 shamTMS, long-term addicts | 5 2000 | 10 Hz 100% | L DLPFC NS, no MRI | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | VAS * (cue-induced) Before, after 1st and last session | Significant effect on craving at day 1 and 5 |

| Stimulant group | ||||||||

| Nicotine | ||||||||

| Johann et al., 2003 [102] | RCT, DB, crossover, 2 consecutive days | 11, 2 M/9 F, motivated to quit | 1 1000 | 20 Hz 90% | L DLPFC NS | Figure-of-8 45–90° angulation | VAS * | Significant craving reduction |

| Amiaz et al., 2009 [93] | RCT, DB, 4 arms: real/shamTMS, smoke/neutral cue | 48, 26 real/22 shamTMS (smoke cue: 12/9), 21 M/27 F, ≥20 cig/day | 10 and maintenance phase: 6 over 1 month 1000 | 10 Hz 100% | L DLPFC 5 cm | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | Cue-induced craving * by VAS and sTCQ, Consumption and nicotine dependence (FTND) Before, after rTMS and at 6 months | Significant effect on cue-induced-smoke craving, on consumption and dependence No difference at 6 months |

| Rose et al., 2011 [88] | RCT, crossover, 3 visits (1 Hz, 10 Hz, and shamTMS) | 15, 8 M/7 F, ≥20 cig/day, with good cue reactivity | 1 at each frequency 1 Hz: 450/10 Hz: 4500 | 1 and 10 Hz 90% | SFG 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS: motor cortex stimulation | Shiffman–Jarvik questionnaire (cue-induced, neutral/smoke) * Cigarette evaluation questionnaire | Cue-induced craving increase at 10 Hz but decrease if neutral cue |

| Li et al., 2013 [103] | RCT, DB, crossover, 1 week washout | 14 (16 included), 10 M/4 F, non-treatment-seeking | 1 3000 | 10 Hz 100% | L DLPFC 6 cm | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | QSU-B (cue-induced, neutral/smoke) * | Significant effect on craving, correlated with dependence severity |

| Pripfl et al., 2014 [87] | RCT, cross over, 1 week washout | 11 (14 included), 5 M/6 F, abstinent for 6 h | 1 1200 | 10 Hz 90% | L DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS: vertex stimulation | 5 points LS (cue-induced) * EEG | Significant reduction in craving and EEG delta power |

| Diehler et al., 2014 [95] | RCT, DB Add-on a 6-sessions group CBT, rTMS at meetings 3 to 6 | 74, 38 real/36 shamTMS, 40 M/34 F | 4 (2/week) 600 | iTBS 80% | R DLPFC 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS: 45° angulation and 60% RMT | QSU * before CBT and after last rTMS session Abstinence rate at 3, 6, and 12 months | No effect on craving Significant effect on abstinence rate at 3 months |

| Trojak et al., 2015 [111] | RCT, DB Phase 1: rTMS + NRT (2 weeks) Phase 2: NRT only (4 weeks) Phase 3: follow-up (6 weeks) | 37, 18 real/19 shamTMS, 20 M/17 F, motivated to quit, at least 2 unsuccessful attempts to quit | 10 360 | 1 Hz 120% | R DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS, FTCQ-12, and QSU Abstinence rate Before and after rTMS, week 6 and 12 | No significant effect of add-on rTMS on craving but effect on abstinence rate, without lasting effect |

| Li et al., 2017 [104] | RCT, SB, crossover, 1 week washout | 11, 5 M/6 F | 1 3000 | 10 Hz 100% | L DLPFC 6 cm | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced) Resting state fMRI | No effect on craving Decreased fALFF in the right insula and thalamus and temporal connectivity between L DLPFC and L OMPFC |

| Cocaine | ||||||||

| Hanlon et al., 2015 [80] | RCT, SB, crossover, 7–14 days washout | 11, 9 M/2 F, non-treatment-seeking | 1 3600 | cTBS 110% | L MPFC 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS * fMRI | Significant decrease in craving and striatum and ant insula activity |

| Hanlon et al., 2017 ** [98] | RCT, SB, crossover, 7–14 days washout | 25, 12 M/13 F, non-treatment-seeking chronic cocaine users abstinent for 48 h | 1 3600 | cTBS 110% | L FP 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced) fMRI before and after cTBS (change in MPFC–striatal connectivity) | No effect on craving Decreased evoked BOLD signal in the caudate, accumbens, anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal and parietal cortex |

| Methamphetamine | ||||||||

| Li et al., 2013 [89] | RCT, SB, crossover, 1 h washout | 18, 10 MA dependent and 8 healthy controls, 4 M/14 F | 1 900 | 1 Hz 100% | L DLPFC 6 cm | Figure-of-8 45° angulation | VAS (cue-induced, neutral/MA) * during rTMS session | For MA dependent only: significant craving increase |

| Liu et al., 2017 [85] | 5 arms (10 Hz P3 = shamTMS, 10 Hz L DLPFC, 10 Hz R DLPFC, 1 Hz L DLPFC, 1 Hz R DLPFC) | 50 M, detoxified for the last 2 months | 5 10 Hz: 2000 1 Hz: 600 | 1 Hz/10 Hz 100%RMT | L DLPFC R DLPFC 10–20 syst | Round coil ShamTMS condition = P3 | VAS (cue-induced) * prior to rTMS stimulation, 30 min after rTMS on day 1 and on day 5 | Significant decrease in craving after either at left or right side, both high and low frequency rTMS, but not after shamTMS condition |

| Su et al., 2017 [109] | RCT, DB | 30 M, 15 real/15 shamTMS | 5 1200 | 10 Hz 80% | L DLPFC 5 cm | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | VAS (cue-induced) * Cognitive functions HDRS, HARS, PSQI | Significant decrease in craving, improvement in verbal learning, memory and social cognition |

| Liang et al., 2018 [84] | RCT, DB | 48 M, 24 real/24 shamTMS | 10 (12 days) 2000 | 10 Hz NS | L DLPFC NS, no MRI | NS | VAS (cue-induced) Withdrawal symptoms, quality of sleep, depression, and anxiety | Significant craving reduction Improvement in sleep, depression, and anxiety Withdrawal symptoms reduction in both groups |

| Su et al., 2020 [110] | RCT, DB | 126, 70 real/56 shamTMS, 106 M/20 F | 20 (4 weeks) 900 | iTBS 100% | L DLPFC 10–20 syst | Figure-of-8 180° angulation | VAS (cue-induced) * at baseline and after each 5 sessions Sleep quality at baseline and after sessions, cognitive functions: at baseline, 1 month, and 12 months | Significant craving reduction Improvement in sleep quality and cognitive functions |

| Yuan et al., 2020 [90] | RCT, DB | 73 M, 37 real/36 shamTMS | 10 600 | 1 Hz 100% | L DLPFC 5 cm | Figure-of-8 90° angulation | Craving (cue-induced) Impulse inhibition (2-choice odd-ball task) After 1 session, 24 h after 10 sessions, and at 3 weeks follow-up | Significant craving decrease and improvement in response inhibition, both lasting 3 weeks after treatment |

| Behavioral group | ||||||||

| Eating Disorder | ||||||||

| Van den Eynde et al., 2010 [112] | RCT, DB | 38, 17 real/20 shamTMS, 5 M/33 F BN or EDNOS-BN, fasting 2 h before | 1 1000 | 10 Hz 110% | L DLPFC 5 cm | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced, FCT) * and FCQ-S No. of binges over the 24 h after rTMS | Significant diminution of cue-induced craving and No. of binges but no effect on FCQ-S |

| Gay et al., 2016 [96] | RCT, DB | 47 F, 23 real/24 shamTMS BN | 10 1000 | 10 Hz 110% | L DLPFC 6 cm | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced, FCT) before and after first and last rTMS session No. of bingeing and purging episodes in the 15 days following last session, MADRS | No significant effect on cue-induced craving or binge episode |

| McClelland, 2016 [105] | RCT | 49 F, 21 real/28 shamTMS 28 AN-R, 21 AN-BP Mean BMI: 16.5 | 1 session 1000 | 10 Hz 110% | L DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 | After FCT, combination of AN-related experiences evaluated by VAS of which urge to restrict * Mood, temporal discounting (TD), and salivary cortisol Before, after rTMS, and 24 h following | No significant effect of rTMS but a trend on core AN symptoms, maintained at 24 h, and on TD No effect on cortisol |

| Gambling disorder | ||||||||

| Zack et al., 2016 [113] | RCT, DB, 3 * 3 (rTMS, cTBS, shamTMS), crossover, 1 week washout | 9 M, non-treatment-seeking | 1 of each rTMS: 450 cTBS: 900 | 10 Hz et cTBS 80% | rTMS: MPFC cTBS: R DLPFC Neuronavigation | rTMS: double cone coil cTBS: figure-of-8 ShamTMS: vertex stimulation | VAS (cue-induced, slot machine) Cognitive tests: DDT, Stroop test Amount of money and frequency of gambling | Significant effect of rTMS only on craving No effect on impulsive choice and decrease in control with rTMS and cTBS No effect on gambling behavior |

| Gay et al., 2017 [97] | RCT, DB, crossover, 1 week washout | 22, 14 M/8 F, treatment-seeking | 1 3008 | 10 Hz 110% | L DLPFC Neuronavigation | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced) * Gambling behavior before and 7 days after rTMS | Significant effect on craving, no effect on gambling behavior |

| Sauvaget et al., 2018 [89] | RCT, DB, crossover, 1–2 weeks washout | 30 | 1 360 | 1 Hz 120% | R DLPFC Beam F3 method | Figure-of-8 ShamTMS coil | VAS (cue-induced) * GACS-desire factor, heart rate, blood pressure | No effect on craving and other outcomes |

References

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM Library; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Gearhardt, A.N.; White, M.A.; Potenza, M.N. Binge eating disorder and food addiction. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2011, 4, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hadad, N.A.; Knackstedt, L.A. Addicted to palatable foods: Comparing the neurobiology of Bulimia Nervosa to that of drug addiction. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 1897–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kalivas, P.W.; Volkow, N.D. The neural basis of addiction: A pathology of motivation and choice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.M.L.; Dowling, N.A.; Jackson, A.C.; Shek, D.T. Gambling related family coping and the impact of problem gambling on families in Hong Kong. Asian J. Gambl. Issues Public Health 2016, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.E.; Myers, T.; Crosby, R.; O’Neill, G.; Carlisle, J.; Gerlach, S. Health care utilization in patients with eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2009, 42, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; DeBar, L.; Wilson, G.T.; Dickerson, J.; Rosselli, F.; Perrin, N.; Lynch, F.; Kraemer, H.C. Health services use in eating disorders. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, C.P. Review, Evidence-based treatments of addiction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.; Minozzi, S.; Davoli, M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 6, CD008537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, W.P.; Soares, B.G.O.; Farrel, M.; Lima, M.S. Psychosocial interventions for cocaine and psychostimulant amphetamines related disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 3, CD003023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, L.F.; Koilpillai, P.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lancaster, T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 3, CD008286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, M.N.; Sofuoglu, M.; Carroll, K.M.; Rounsaville, B.J. Neuroscience of behavioral and pharmacological treatments for addictions. Neuron 2011, 69, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Achab, S.; Khazaal, Y. Psychopharmacological treatment in pathological gambling: A critical review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolt, D.M.; Piper, M.E.; Theobald, W.E.; Baker, T.B. Why two smoking cessation agents work better than one: Role of craving suppression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mariani, J.J.; Levin, F.R. Psychostimulant treatment of cocaine dependence. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 35, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, C.A.; Geisel, O.; Banas, R.; Heinz, A. Current pharmacological treatment approaches for alcohol dependence. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. Addiction and dependence in DSM-V. Addiction 2011, 106, 866–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skinner, M.D.; Aubin, H.-J. Craving’s place in addiction theory: Contributions of the major models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.M.; Wohl, M.J.A. The Gambling Craving Scale: Psychometric validation and behavioral outcomes. Psychol. Addict. Behav. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009, 23, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.M.; Daams, J.G.; Koeter, M.W.J.; Veltman, D.J.; van den Brink, W.; Goudriaan, A.E. Effects of non-invasive neurostimulation on craving: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 2472–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelchat, M.L. Food addiction in humans. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafioun, L.; Rosenberg, H. Methods of assessing craving to gamble: A narrative review. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012, 26, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, H. Clinical and laboratory assessment of the subjective experience of drug craving. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffany, S.T.; Wray, J.M. The clinical significance of drug craving: Tiffany & Wray. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1248, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addolorato, G.; Abenavoli, L.; Leggio, L.; Gasbarrini, G. How many cravings? Pharmacological aspects of craving treatment in alcohol addiction: A review. Neuropsychobiology 2005, 51, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslin, D.W.; Cary, M.; Slaymaker, V.; Colleran, C.; Blow, F.C. Daily ratings measures of alcohol craving during an inpatient stay define subtypes of alcohol addiction that predict subsequent risk for resumption of drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 103, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, P.; Hyman, S.M.; Sinha, R. Craving predicts time to cocaine relapse: Further validation of the Now and Brief versions of the cocaine craving questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 93, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinha, R.; Garcia, M.; Paliwal, P.; Kreek, M.J.; Rounsaville, B.J. Stress-induced cocaine craving and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses are predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hodgins, D.C.; el-Guebaly, N. Retrospective and prospective reports of precipitants to relapse in pathological gambling. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinska, A.J.; Stein, E.A.; Kaiser, J.; Naumer, M.J.; Yalachkov, Y. Factors modulating neural reactivity to drug cues in addiction: A survey of human neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kober, H.; Lacadie, C.M.; Wexler, B.E.; Malison, R.T.; Sinha, R.; Potenza, M.N. Brain Activity During Cocaine Craving and Gambling Urges: An fMRI Study. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 41, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Lim, Y.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Graham, S.J. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) study of cue-induced smoking craving in virtual environments. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2005, 30, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbrick-Oldfield, E.H.; Mick, I.; Cocks, R.E.; McGonigle, J.; Sharman, S.P.; Goldstone, A.P.; Stokes, P.R.A.; Waldman, A.; Erritzoe, D.; Bowden-Jones, H.; et al. Neural substrates of cue reactivity and craving in gambling disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J.; Ma, Y.; Fowler, J.S.; Wong, C.; Ding, Y.-S.; Hitzemann, R.; Swanson, J.M.; Kalivas, P. Activation of orbital and medial prefrontal cortex by methylphenidate in cocaine-addicted subjects but not in controls: Relevance to addiction. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 3932–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, R.Z.; Volkow, N.D. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Le Moal, M. Drug abuse: Hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science 1997, 278, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, K.C. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: The case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 2007, 191, 391–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Fowler, J.S.; Wang, G.J.; Baler, R.; Telang, F. Imaging dopamine’s role in drug abuse and addiction. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56 (Suppl. S1), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bestmann, S.; Baudewig, J.; Siebner, H.R.; Rothwell, J.C.; Frahm, J. BOLD MRI responses to repetitive TMS over human dorsal premotor cortex. NeuroImage 2005, 28, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.S.; Farzan, F.; Rusjan, P.M.; Chen, R.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Daskalakis, Z.J. Potentiation of Gamma Oscillatory Activity through Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 2359–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, S.S.; Strafella, A.P. rTMS of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Modulates Dopamine Release in the Ipsilateral Anterior Cingulate Cortex and Orbitofrontal Cortex. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strafella, A.P.; Paus, T.; Fraraccio, M.; Dagher, A. Striatal dopamine release induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain 2003, 126, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamoli, E.; Manganotti, P.; Schwartz, R.P.; Rimondo, C.; Gomma, M.; Serpelloni, G. rTMS in the treatment of drug addiction: An update about human studies. Behav. Neurol. 2014, 2014, 815215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, P.; Ingham, R.; George, M.S.; Mayberg, H.; Ingham, J.; Roby, J.; Martin, C.; Jerabek, P. Imaging human intra-cerebral connectivity by PET during TMS. Neuroreport 1997, 8, 2787–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, D.A.; Zangen, A.; George, M.S. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of substance addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1327, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roth, Y.; Zangen, A.; Hallett, M. A coil design for transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. Publ. Am. Electroencephalogr. Soc. 2002, 19, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangen, A.; Roth, Y.; Voller, B.; Hallett, M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: Evidence for efficacy of the H-coil. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2005, 116, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovitz, Y.; Harel, E.V.; Roth, Y.; Braw, Y.; Most, D.; Katz, L.N.; Sheer, A.; Gersner, R.; Zangen, A. Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation over the prefrontal cortex: Evaluation of antidepressant and cognitive effects in depressive patients. Brain Stimulat. 2009, 2, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Leone, A.; Valls-Solé, J.; Wassermann, E.M.; Hallett, M. Responses to rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain J. Neurol. 1994, 117 Pt 4, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-Z.; Edwards, M.J.; Rounis, E.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 2005, 45, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; André-Obadia, N.; Antal, A.; Ayache, S.S.; Baeken, C.; Benninger, D.H.; Cantello, R.M.; Cincotta, M.; de Carvalho, M.; De Ridder, D.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 2150–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Sustained Excitability Elevations Induced by Transcranial DC Motor Cortex Stimulation in Humans. Neurology 2001, 57, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Zilverstand, A.; Gui, W.; Li, H.-J.; Zhou, X. Effects of single-session versus multi-session non-invasive brain stimulation on craving and consumption in individuals with drug addiction, eating disorders or obesity: A meta-analysis. Brain Stimulat. 2019, 12, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.B.; Sesack, S.R. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: Target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 3864–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diana, M. The dopamine hypothesis of drug addiction and its potential therapeutic value. Front. Psychiatry 2011, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettorruso, M.; di Giannantonio, M.; De Risio, L.; Martinotti, G.; Koob, G.F. A Light in the Darkness: Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) to Treat the Hedonic Dysregulation of Addiction. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, L.; Pettorruso, M.; De Crescenzo, F.; De Risio, L.; di Nuzzo, L.; Martinotti, G.; Bifone, A.; Janiri, L.; Di Nicola, M. Neural correlates of cognitive control in gambling disorder: A systematic review of fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 78, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavan, H.; Hester, R. The role of cognitive control in cocaine dependence. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2007, 17, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Holst, R.J.; Schilt, T. Drug-related decrease in neuropsychological functions of abstinent drug users. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2011, 4, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney-Ramos, T.E.; Dowdle, L.T.; Lench, D.H.; Mithoefer, O.J.; Devries, W.H.; George, M.S.; Anton, R.F.; Hanlon, C.A. Transdiagnostic Effects of Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Cue Reactivity. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enokibara, M.; Trevizol, A.; Shiozawa, P.; Cordeiro, Q. Establishing an effective TMS protocol for craving in substance addiction: Is it possible? Am. J. Addict. Am. Acad. Psychiatr. Alcohol. Addict. 2016, 25, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, C.J.; Vincent, C.; Hall, P.A. Effects of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation on Food Cravings and Consumption: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychosom. Med. 2017, 79, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Sun, Y.; Ku, Y. Effects of Non-invasive Brain Stimulation on Stimulant Craving in Users of Cocaine, Amphetamine, or Methamphetamine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, R.; Mishra, B.R.; Hota, D. Effect of High-Frequency Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Craving in Substance Use Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 29, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, S.-A.; Khaleghi, A.; Mohammadi, M.R. Noninvasive brain stimulation in alcohol craving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 101, 109938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.Q.; Fong, K.N.K.; Ouyang, R.-G.; Siu, A.M.H.; Kranz, G.S. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on craving and substance consumption in patients with substance dependence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2019, 114, 2137–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grall-Bronnec, M.; Sauvaget, A. The use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for modulating craving and addictive behaviours: A critical literature review of efficacy, technical and methodological considerations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 47, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.1 (Updated September 2020); Cochrane: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hone-Blanchet, A.; Ciraulo, D.A.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Fecteau, S. Noninvasive brain stimulation to suppress craving in substance use disorders: Review of human evidence and methodological considerations for future work. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 59, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited, Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 45, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hozo, S.P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Hozo, I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2010, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curtin, F. Meta-analysis combining parallel and cross-over trials with random effects. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, C.A.; Dowdle, L.T.; Austelle, C.W.; DeVries, W.; Mithoefer, O.; Badran, B.W.; George, M.S. What goes up, can come down: Novel brain stimulation paradigms may attenuate craving and craving-related neural circuitry in substance dependent individuals. Brain Res. 2015, 1628, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Höppner, J.; Broese, T.; Wendler, L.; Berger, C.; Thome, J. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treatment of alcohol dependence. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 12, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.M.; van den Heuvel, O.A.; van der Werf, Y.D.; de Wit, S.J.; Veltman, D.J.; van den Brink, W.; Goudriaan, A.E. The Effect of High-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Emotion Processing, Reappraisal, and Craving in Alcohol Use Disorder Patients and Healthy Controls: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Malcolm, R.J.; Huebner, K.; Hanlon, C.A.; Taylor, J.J.; Brady, K.T.; George, M.S.; See, R.E. Low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex transiently increases cue-induced craving for methamphetamine: A preliminary study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 133, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yuan, T.-F. Targeting Withdrawal Symptoms in Men Addicted to Methamphetamine with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 1199–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Yuan, T.-F. Either at left or right, both high and low frequency rTMS of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex decreases cue induced craving for methamphetamine. Am. J. Addict. 2017, 26, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, I.; Kämpe, R.; Arlestig, T.; Karlsson, H.; Löfberg, A.; Pietrzak, M.; Zangen, A.; Heilig, M. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation targeting the insular cortex for reduction of heavy drinking in treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent subjects: A randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 19, 0565-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pripfl, J.; Tomova, L.; Riecansky, I.; Lamm, C. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Decreases Cue-induced Nicotine Craving and EEG Delta Power. Brain Stimulat. 2014, 7, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.E.; McClernon, F.J.; Froeliger, B.; Behm, F.M.; Preud’homme, X.; Krystal, A.D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the superior frontal gyrus modulates craving for cigarettes. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvaget, A.; Bulteau, S.; Guilleux, A.; Leboucher, J.; Pichot, A.; Valrivière, P.; Vanelle, J.-M.; Sébille-Rivain, V.; Grall-Bronnec, M. Both active and sham low-frequency rTMS single sessions over the right DLPFC decrease cue-induced cravings among pathological gamblers seeking treatment: A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, W.; Liang, Q.; Cao, X.; Lucas, M.V.; Yuan, T.-F. Effect of Low-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Impulse Inhibition in Abstinent Patients with Methamphetamine Addiction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Addolorato, G.; Antonelli, M.; Cocciolillo, F.; Vassallo, G.A.; Tarli, C.; Sestito, L.; Mirijello, A.; Ferrulli, A.; Pizzuto, D.A.; Camardese, G.; et al. Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Alcohol Use Disorder Patients: Effects on Dopamine Transporter Availability and Alcohol Intake. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccanti, M.; Inghilleri, M.; Attilia, M.L.; Raccah, R.; Fiore, M.; Zangen, A.; Ceccanti, M. Deep TMS on alcoholics: Effects on cortisolemia and dopamine pathway modulation. A pilot study. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amiaz, R.; Levy, D.; Vainiger, D.; Grunhaus, L.; Zangen, A. Repeated high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces cigarette craving and consumption. Addiction 2009, 104, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Felice, A.; Bellamoli, E.; Formaggio, E.; Manganotti, P.; Masiero, S.; Cuoghi, G.; Rimondo, C.; Genetti, B.; Sperotto, M.; Corso, F.; et al. Neurophysiological, psychological and behavioural correlates of rTMS treatment in alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 158, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieler, A.C.; Dresler, T.; Joachim, K.; Deckert, J.; Herrmann, M.J.; Fallgatter, A.J. Can intermittent theta burst stimulation as add-on to psychotherapy improve nicotine abstinence? Results from a pilot study. Eur. Addict. Res. 2014, 20, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gay, A.; Jaussent, I.; Sigaud, T.; Billard, S.; Attal, J.; Seneque, M.; Galusca, B.; Van Den Eynde, F.; Massoubre, C.; Courtet, P.; et al. A Lack of Clinical Effect of High-frequency rTMS to Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex on Bulimic Symptoms: A Randomised, Double-blind Trial. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2016, 24, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, A.; Boutet, C.; Sigaud, T.; Kamgoue, A.; Sevos, J.; Brunelin, J.; Massoubre, C. A single session of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex reduces cue-induced craving in patients with gambling disorder. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2017, 41, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, C.; Dowdle, L.; Anton, R.; George, M. Ventral medial prefrontal cortex theta burst stimulation decreases salience network activity in cocaine users and alcohol users. Brain Stimul. Basic Transl. Clin. Res. Neuromodul. 2017, 10, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, S.C.; Baeken, C.; Vanderbruggen, N.; Vanderhasselt, M.A.; Zeeuws, D.; Santermans, L.; De Raedt, R. No influence of one right-sided prefrontal HF-rTMS session on alcohol craving in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients: Results of a naturalistic study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 120, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herremans, S.C.; Vanderhasselt, M.-A.; De Raedt, R.; Baeken, C. Reduced Intra-individual Reaction Time Variability During a Go-NoGo Task in Detoxified Alcohol-Dependent Patients After One Right-Sided Dorsolateral Prefrontal HF-rTMS Session. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013, 48, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herremans, S.C.; De Raedt, R.; Van Schuerbeek, P.; Marinazzo, D.; Matthys, F.; De Mey, J.; Baeken, C. Accelerated HF-rTMS Protocol has a Rate-Dependent Effect on dACC Activation in Alcohol-Dependent Patients: An Open-Label Feasibility Study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, M.; Wiegand, R.; Kharraz, A.; Bobbe, G.; Sommer, G.; Hajak, G.; Wodarz, N.; Eichhammer, P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for nicotine dependence. Psychiatr. Prax. 2003, 30 (Suppl. S2), S129–S131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hartwell, K.J.; Owens, M.; LeMatty, T.; Borckardt, J.J.; Hanlon, C.A.; Brady, K.T.; George, M.S. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Reduces Nicotine Cue Craving. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Du, L.; Sahlem, G.L.; Badran, B.W.; Henderson, S.; George, M.S. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces resting-state insula activity and modulates functional connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex in cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 174, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McClelland, J.; Kekic, M.; Bozhilova, N.; Nestler, S.; Dew, T.; Van den Eynde, F.; David, A.S.; Rubia, K.; Campbell, I.C.; Schmidt, U. A Randomised Controlled Trial of Neuronavigated Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) in Anorexia Nervosa. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishra, B.R.; Nizamie, S.H.; Das, B.; Praharaj, S.K. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in alcohol dependence: A sham-controlled study: Efficacy of rTMS in alcohol dependence. Addiction 2010, 105, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlem, G.L.; Baker, N.L.; George, M.S.; Malcolm, R.J.; McRae-Clark, A.L. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) administration to heavy cannabis users. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2018, 44, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Cao, X.; Tan, T.; Shan, C.; Wang, Y.; Pan, J.; He, H.; Yuan, T.-F. 10-Hz Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Reduces Heroin Cue Craving in Long-Term Addicts. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Zhong, N.; Gan, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Ruan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; et al. High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for methamphetamine use disorders: A randomised clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 175, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Chen, T.; Jiang, H.; Zhong, N.; Du, J.; Xiao, K.; Xu, D.; Song, W.; Zhao, M. Intermittent theta burst transcranial magnetic stimulation for methamphetamine addiction: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. J. Eur. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 31, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojak, B.; Meille, V.; Achab, S.; Lalanne, L.; Poquet, H.; Ponavoy, E.; Blaise, E.; Bonin, B.; Chauvet-Gelinier, J.-C. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Combined with Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Stimulat. 2015, 8, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, F.; Claudino, A.M.; Mogg, A.; Horrell, L.; Stahl, D.; Ribeiro, W.; Uher, R.; Campbell, I.; Schmidt, U. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces cue-induced food craving in bulimic disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, M.; Cho, S.S.; Parlee, J.; Jacobs, M.; Li, C.; Boileau, I.; Strafella, A. Effects of High Frequency Repeated Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Continuous Theta Burst Stimulation on Gambling Reinforcement, Delay Discounting, and Stroop Interference in Men with Pathological Gambling. Brain Stimulat. 2016, 9, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meule, A.; Gearhardt, A. Food Addiction in the Light of DSM-5. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3653–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, K.S.; Rydin-Gray, S.; Kose, S.; Borckardt, J.J.; O’Neil, P.M.; Shaw, D.; Madan, A.; Budak, A.; George, M.S. Food cravings and the effects of left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation using an improved sham condition. Front. Psychiatry 2011, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uher, R.; Yoganathan, D.; Mogg, A.; Eranti, S.V.; Treasure, J.; Campbell, I.C.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Schmidt, U. Effect of left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on food craving. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badiani, A.; Belin, D.; Epstein, D.; Calu, D.; Shaham, Y. Opiate versus psychostimulant addiction: The differences do matter. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomis-Vicent, E.; Thoma, V.; Turner, J.J.D.; Hill, K.P.; Pascual-Leone, A. Review: Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation in Behavioral Addictions: Insights from Direct Comparisons with Substance Use Disorders. Am. J. Addict. 2019, 28, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Perini, I.; Kämpe, R.; Alyagon, U.; Shalev, H.; Besser, I.; Sommer, W.H.; Heilig, M.; Zangen, A. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled Proof-of-Concept Trial Targeting the Medial Prefrontal and Anterior Cingulate Cortices. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaudias, V.; Heeren, A.; Brousse, G.; Maurage, P. Toward a Triadic Approach to Craving in Addictive Disorders: The Metacognitive Hub Model. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojak, B.; Meille, V.; Chauvet-Gelinier, J.-C.; Bonin, B. Further evidence of the usefulness of MRI-based neuronavigation for the treatment of depression by rTMS. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 23, E30–E31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Cabré, A.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Rushmore, R.J. Cumulative sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) build up facilitation to subsequent TMS-mediated behavioural disruptions. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 27, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachid, F. Maintenance repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for relapse prevention in with depression: A review. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangen, A.; Moshe, H.; Martinez, D.; Barnea-Ygael, N.; Vapnik, T.; Bystritsky, A.; Duffy, W.; Toder, D.; Casuto, L.; Grosz, M.L.; et al. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Smoking Cessation: A Pivotal Multicenter Double-blind Randomized Controlled Trial. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, G.; Terraneo, A.; Cardullo, S.; Gómez Pérez, L.J.; Cellini, N.; Sarlo, M.; Bonci, A.; Gallimberti, L. Long-Term Outcome of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in a Large Cohort of Patients with Cocaine-Use Disorder: An Observational Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Effect Size | Heterogeneity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k * | Hedge’s g (Random Effect) | CI 95% | Z-Statistic | p | p | I2 | |

| Target and frequency | |||||||

| HF Left DLPFC | 12 | −0.396 | −0.603; −0.190 | 3.76 | <0.001 | 0.656 | 0 |

| LF Left DLPFC | 1 | −0.670 | −1.142; −0.198 | 2.78 | <0.001 | - | - |

| LF Right DLPFC | 3 | −0.120 | −0.488; 0.249 | 0.64 | 0.524 | 0.637 | 0 |

| HF MPFC | 1 | −0.781 | −1.744; 0.182 | 1.59 | 0.112 | - | - |

| LF MPFC | 2 | −0.108 | −0.570; 0.355 | 0.46 | 0.648 | 0.976 | 0 |

| LF SFG | 1 | −0.175 | −0.892; 0.542 | 0.48 | 0.633 | - | - |

| Method of localization | |||||||

| No neuronavigation | 14 | −0.352 | −0.531; −0.173 | 3.86 | <0.001 | 0.678 | 0 |

| Neuronavigation | 6 | −0.328 | −0.620; −0.037 | 2.21 | 0.027 | 0.436 | 0 |

| Number of sessions | |||||||

| Single | 14 | −0.354 | −0.540; −0.169 | 3.74 | <0.001 | 0.934 | 0 |

| Multiple | 6 | −0.321 | −0.687; 0.045 | 1.72 | 0.086 | 0.121 | 42.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gay, A.; Cabe, J.; De Chazeron, I.; Lambert, C.; Defour, M.; Bhoowabul, V.; Charpeaud, T.; Tremey, A.; Llorca, P.-M.; Pereira, B.; et al. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) as a Promising Treatment for Craving in Stimulant Drugs and Behavioral Addiction: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030624

Gay A, Cabe J, De Chazeron I, Lambert C, Defour M, Bhoowabul V, Charpeaud T, Tremey A, Llorca P-M, Pereira B, et al. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) as a Promising Treatment for Craving in Stimulant Drugs and Behavioral Addiction: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(3):624. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030624

Chicago/Turabian StyleGay, Aurélia, Julien Cabe, Ingrid De Chazeron, Céline Lambert, Maxime Defour, Vikesh Bhoowabul, Thomas Charpeaud, Aurore Tremey, Pierre-Michel Llorca, Bruno Pereira, and et al. 2022. "Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) as a Promising Treatment for Craving in Stimulant Drugs and Behavioral Addiction: A Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 3: 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030624

APA StyleGay, A., Cabe, J., De Chazeron, I., Lambert, C., Defour, M., Bhoowabul, V., Charpeaud, T., Tremey, A., Llorca, P.-M., Pereira, B., & Brousse, G. (2022). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) as a Promising Treatment for Craving in Stimulant Drugs and Behavioral Addiction: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(3), 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030624