Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long COVID: A Narrative Review Focusing on the Assessment and Rehabilitative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Methodology

3. Neurological Manifestations of Long COVID

4. Cognitive Dysfunctions, Psychiatric Symptoms, and Behavioral Alterations

5. Psychometric Assessment and Neurorehabilitative Approach

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarker, A.; Ge, Y. Mining long-COVID symptoms from Reddit: Characterizing post-COVID syndrome from patient reports. JAMIA Open 2021, 4, ooab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haran, J.P.; Bradley, E.; Zeamer, A.L.; Cincotta, L.; Salive, M.C.; Dutta, P.; Mutaawe, S.; Anya, O.; Meza-Segura, M.; Moormann, A. Inflammation-type dysbiosis of the oral microbiome associates with the duration of COVID-19 symptoms and long COVID. JCI Insight. 2021, 6, e152346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondelli, V.; Pariante, C.M. What can neuroimmunology teach us about the symptoms of long-COVID? Oxford Open Immunol. 2021, 2, iqab004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.; Haldar, S.N.; Soneja, M.; Mundadan, N.G.; Garg, P.; Mittal, A.; Desai, D.; Trilangi, P.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Begam, N.N.; et al. Post COVID-19 sequelae: A prospective observational study from Northern India. Drug Discov. Ther. 2021, 15, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O’Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raison, C.L.; Lin, J.M.; Reeves, W.C. Association of peripheral inflammatory markers with chronic fatigue in a population-based sample. Brain Behav. Immun. 2009, 23, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, V.; Vernon, A.C.; Turkheimer, F.; Dazzan, P.; Pariante, C.M. Brain microglia in psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.; Hepgul, N.; Nikkheslat, N.; Borsini, A.; Zajkowska, Z.; Moll, N.; Forton, D.; Agarwal, K.; Chalder, T.; Mondelli, V.; et al. Persistent fatigue induced by interferon-alpha: A novel, inflammation-based, proxy model of chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, D.S.; Forsberg, A.; Sandstrom, A.; Bergan, C.; Kadetoff, D.; Protsenko, E.; Lampa, J.; Lee, Y.C.; Höglund, C.O.; Catana, C.; et al. Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia—A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 75, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsland, A.L.; Gianaros, P.J.; Kuan, D.C.; Sheu, L.K.; Krajina, K.; Manuck, S.B. Brain morphology links systemic inflammation to cognitive function in midlife adults. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, M.I.; Palaiodimou, L.; Bakola, E.; Smyrnis, N.; Papadopoulou, M.; Paraskevas, G.P.; Rizos, E.; Boutati, E.; Grigoriadis, N.; Krogias, C.; et al. Neurological manifestations of long-COVID syndrome: A narrative review. Ther. Adv. Chronic. Dis. 2022, 13, 20406223221076890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeßle, J.; Waterboer, T.; Hippchen, T.; Simon, J.; Kirchner, M.; Lim, A.; Müller, B.; Merle, U. Persistent Symptoms in Adult Patients 1 Year After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, K.M.A.; Saunders, K.; Uddin, Z.; Walton, L.M.; Raigangar, V.; Sakel, M.; Shafin, R.; Hossain, M.S.; Kabir, M.F.; et al. Prevalence of Long COVID symptoms in Bangladesh: A prospective Inception Cohort Study of COVID-19 survivors. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelletti, P.; Bentivegna, E.; Spuntarelli, V.; Luciani, M. Long-COVID Headache. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021, 3, 1704–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanares-Zapatero, D.; Chalon, P.; Kohn, L.; Dauvrin, M.; Detollenaere, J.; Maertens de Noordhout, C.; Primus-de Jong, C.; Cleemput, I.; Van den Heede, K. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: A comprehensive review. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torjesen, I. COVID-19: Long COVID symptoms among hospital inpatients show little improvement after a year, data suggest. BMJ 2021, 375, n3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, G.; Monaghan, A.; Xue, F.; Duggan, E.; Romero-Ortuño, R. Comprehensive Clinical Characterisation of Brain Fog in Adults Reporting Long COVID Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampshire, A.; Trender, W.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Jolly, A.E.; Grant, J.E.; Patrick, F.; Mazibuko, N.; Williams, S.C.; Barnby, J.M.; Hellyer, P.; et al. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocsovszky, Z.; Otohal, J.; Berényi, B.; Juhász, V.; Skoda, R.; Bokor, L.; Dohy, Z.; Szabó, L.; Nagy, G.; Becker, D.; et al. The associations of long-COVID symptoms, clinical characteristics and affective psychological constructs in a non-hospitalized cohort. Physiol. Int. 2022, 109, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelin, D.; Margalit, I.; Nehme, M.; Bordas-Martínez, J.; Pistelli, F.; Yahav, D.; Guessous, I.; Durà-Miralles, X.; Carrozzi, L.; Shapira-Lichter, I.; et al. Patterns of Long COVID Symptoms: A Multicenter Cross Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, C.; Borgonovo, F.; Capetti, A.F.; Oreni, L.; Cossu, M.V.; Pellicciotta, M.; Armiento, L.; Bocchio, S.; Dedivitiis, G.; Lupo, A.; et al. Persistence of Long-COVID symptoms in a heterogenous prospective cohort. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 722–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, A.; Aughterson, H.; Fancourt, D.; Philip, K.E.J. Factors shaping the mental health and well-being of people experiencing persistent COVID-19 symptoms or ‘long COVID’: Qualitative study. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaksi, N.; Teker, A.G.; Imre, A. Long COVID in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Iran J. Public Health 2022, 51, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, C.; Baek, G. Symptoms and management of long COVID: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.W.; Leonard, B.E.; Helmeste, D.M. Long COVID, neuropsychiatric disorders, psychotropics, present and future. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2022, 34, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurology, T.L. The Lancet Neurology. Long COVID: Understanding the Neurological Effects. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, G.; Bertelloni, D.; Diolaiuti, F.; Mucci, F.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Biella, M.; Gemignani, A.; Ciacchini, R.; Conversano, C. Long-COVID Syndrome? A Study on the Persistence of Neurological, Psychological and Physiological Symptoms. Healthcare 2021, 9, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premraj, L.; Kannapadi, N.V.; Briggs, J.; Seal, S.M.; Battaglini, D.; Fanning, J.; Suen, J.; Robba, C.; Fraser, J.; Cho, S.M. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 434, 120162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.D.; Lavelle, M.; Boursiquot, B.C.; Wan, E.Y. Long-term complications of COVID-19. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C1–C11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Jiang, B.C.; Gao, Y.J. Chemokines in neuron-glial cell interaction and pathogenesis of neuropathic pain. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3275–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, G.R.; Wenzel, T.J.; Marshall, N.; Gates, E.J.; Klegeris, A. Targeting toll-like receptor 4 to modulate neuroinflammation in central nervous system disorders. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 865–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Singh, B.; Biswas, G. Corticosteroids: A boon or bane for COVID-19 patients? Steroids 2022, 188, 109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb, C.T.; Goepp, M.; Rossi, A.G.; Yao, C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prostaglandins, and COVID-19. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 4899–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonnesu, R.; Thunuguntla, V.B.S.C.; Veeramachaneni, G.K.; Bondili, J.S.; La Rocca, V.; Filipponi, C.; Spezia, P.G.; Sidoti, M.; Plicanti, E.; Quaranta, P.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Interacting with S Protein and ACE-2 Receptor. Viruses 2022, 14, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caronna, E.; Ballvé, A.; Llauradó, A.; Gallardo, V.J.; Ariton, D.M.; Lallana, S.; López Maza, S.; Olivé Gadea, M.; Quibus, L.; Restrepo, J.L.; et al. Headache: A striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widyadharma, I.P.E.; Sari, N.N.S.P.; Pradnyaswari, K.E.; Yuwana, K.T.; Adikarya, I.P.G.D.; Tertia, C.; Wijayanti, I.; Indrayani, I.; Utami, D. Pain as clinical manifestations of COVID-19 infection and its management in the pandemic era: A literature review. Egypt J. Neurol. Psychiatr. Neurosurg. 2020, 56, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Accessibility Team (RAT). The microvascular hypothesis underlying neurologic manifestations of long COVID-19 and possible therapeutic strategies. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 10, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisanti, S.G.; Garbarino, S.; Barisione, E.; Aloè, T.; Grosso, M.; Schenone, C.; Pardini, M.; Biassoni, E.; Zaottini, F.; Picasso, R.; et al. Neurological long-COVID in the outpatient clinic: Two subtypes, two courses. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 439, 120315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stadio, A.; Brenner, M.J.; De Luca, P.; Albanese, M.; D’Ascanio, L.; Ralli, M.; Roccamatisi, D.; Cingolani, C.; Vitelli, F.; Camaioni, A.; et al. Olfactory Dysfunction, Headache, and Mental Clouding in Adults with Long-COVID-19: What Is the Link between Cognition and Olfaction? A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, E.; Barrett, K.M.S.; Riffle, S.; Bolze, A.; Neveux, I.; Dabe, S.; Joseph, J.; James, T. Long-term COVID-19 symptoms in a large unselected population. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziauddeen, N.; Gurdasani, D.; O’Hara, M.E.; Hastie, C.; Roderick, P.; Yao, G.; Alwan, N.A. Characteristics and impact of Long COVID: Findings from an online survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 17, e0264331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClin. Med. 2021, 38, 3820561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Ballesteros, A.B.; Yeung, S.P.; Liu, R.; Saha, A.; Curtis, L.; Kaser, M.; Haggard, M.P.; Cheke, L.G. COVCOG 1: Factors predicting cognitive symptoms in Long COVID. A first publication from the COVID and Cognition Study. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, R.; Dini, M.; Rosci, C.; Capozza, A.; Groppo, E.; Reitano, M.R.; Allocco, E.; Poletti, B.; Brugnera, A.; Bai, F.; et al. One-year cognitive follow-up of COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 2006–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemanno, F.; Houdayer, E.; Parma, A.; Spina, A.; Del Forno, A.; Scatolini, A.; Angelone, S.; Brugliera, L.; Tettamanti, A.; Beretta, L.; et al. COVID-19 cognitive deficits after respiratory assistance in the subacute phase: A COVID-rehabilitation unit experience. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, R.; Dini, M.; Groppo, E.; Rosci, C.; Reitano, M.R.; Bai, F.; Poletti, B.; Brugnera, A.; Silani, V.; D’Arminio Monforte, A.; et al. Long-Lasting Cognitive Abnormalities after COVID-19. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosp, J.A.; Dressing, A.; Blazhenets, G.; Bormann, T.; Rau, A.; Schwabenland, M.; Thurow, J.; Wagner, D.; Waller, C.; Niesen, W.; et al. Cognitive impairment and altered cerebral glucose metabolism in the subacute stage of COVID-19. Brain 2021, 144, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, J.; Kremer, S.; Merdji, H.; Clere-Jehl, R.; Schenck, M.; Kummerlen, C.; Collange, O.; Boulay, C.; Fafi-Kremer, S.; Ohana, M.; et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2268–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashyna, T.J.; Ely, E.W.; Smith, D.M.; Langa, K.M. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA 2010, 304, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandharipande, P.P.; Girard, T.D.; Jackson, J.C.; Morandi, A.; Thompson, J.L.; Pun, B.T.; Brummel, N.E.; Hughes, C.G.; Vasilevskis, E.E.; Shintani, A.K.; et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeria, M.; Cejudo, J.C.; Sotoca, J.; Deus, J.; Krupinski, J. Cognitive profile following COVID-19 infection: Clinical predictors leading to neuropsychological impairment. Brain Behav. Immunity Health 2020, 9, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.K.; Wang, X.; McCluskey, L.P.; Morgan, J.C.; Switzer, J.A.; Mehta, R.; Tingen, M.; Su, S.; Harris, R.A.; Hess, D.C.; et al. Neuropsychiatric sequelae of long COVID-19: Pilot results from the COVID-19 neurological and molecular prospective cohort study in Georgia, USA. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 24, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, E.L.; Clark, J.R.; Orban, Z.S.; Lim, P.H.; Szymanski, A.L.; Taylor, C.; DiBiase, R.M.; Jia, D.T.; Balabanov, R.; Ho, S.U.; et al. Persistent neurologic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in non-hospitalized COVID-19 long haulers. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, L.W.; Oliveira, S.B.; Moreira, A.S.; Pereira, M.E.; Carneiro, V.S.; Serio, A.S.; Freitas, L.F.; Isidro, H.B.L.; Souza, L.M.N. Neuropsychological manifestations of long COVID in hospitalized and non-hospitalized Brazilian Patients. NeuroRehabilitation 2022, 50, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Z.M.; Nash, R.P.; Laughon, S.L.; Rosenstein, D.L. Neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Harrison, P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: Retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistarini, C.; Fiabane, E.; Houdayer, E.; Vassallo, C.; Manera, M.R.; Alemanno, F. Cognitive and emotional disturbances due to COVID-19: An exploratory study in the rehabilitation setting. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 643646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, D.A.; Chamley, R.; Barker-Davies, R.; O’Sullivan, O.; Ladlow, P.; Mitchell, J.L.; Dewson, D.; Mills, D.; May, S.; Cranley, M.; et al. Comprehensive clinical assessment identifies specific neurocognitive deficits in working-age patients with long-COVID. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.G.; Palladini, M.; De Lorenzo, R.; Magnaghi, C.; Poletti, S.; Furlan, R.; Ciceri, F.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Benedetti, F.; COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study Group. Persistent psychopathology and neurocognitive impairment in COVID-19 survivors: Effect of inflammatory biomarkers at three-month follow-up. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 94, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, I.; Sinatti, G.; Cirella, A.; Santini, S.J.; Balsano, C. Alteration of Inflammatory Parameters and Psychological Post-Traumatic Syndrome in Long-COVID Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 19, 7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasnier, M.; Choucha, W.; Radiguer, F.; Faulet, T.; Chappell, K.; Bougarel, A.; Kondarjian, C.; Thorey, P.; Baldacci, A.; Ballerini, M.; et al. Comorbidity of long COVID and psychiatric disorders after a hospitalisation for COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M.; Hwang, H.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.G.; Yi, Y.H.; Tak, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Chung, S.I. Association between Serum-Ferritin Levels and Sleep Duration, Stress, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Older Koreans: Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2019, 40, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, D.L.; Holdsworth, L.; Jawad, N.; Gunasekera, P.; Morice, A.H.; Crooks, M.G. Post-COVID-19 Symptom Burden: What is Long-COVID and How Should We Manage It? Lung 2021, 199, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, I.W.; Chu, C.M.; Pan, P.C.; Yiu, M.G.; Chan, V.L. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2009, 31, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Park, W.B.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.L.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, H.; Shin, H.-S. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression of survivors 12 months after the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.B.; Shah, A.J.; Saigal, A.; Smith, C.; Brill, S.E.; Goldring, J.; Hurst, J.R.; Jarvis, H.; Lipman, M.; Mandal, S. The high mental health burden of “Long COVID” and its association with on-going physical and respiratory symptoms in all adults discharged from hospital. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2004364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Q.; Jia, C.; Lv, Z.; Yang, J. An Overview of Neurological and Psychiatric Complications During Post-COVID Period: A Narrative Review. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 4199–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Zhao, Y.M.; Yan, W.; Li, C.; Lu, Q.D.; Liu, L.; Ni, S.Y.; Mei, H.; Yuan, K.; Shi, L.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: Call for research priority and action. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douaud, G.; Lee, S.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Arthofer, C.; Wang, C.; McCarthy, P.; Lange, F.; Andersson, J.L.R.; Griffanti, L.; Duff, E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 2022, 604, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Erausquin, G.A.; Snyder, H.; Carrillo, M.; Hosseini, A.A.; Brugha, T.S.; Seshadri, S. CNS SARS-CoV-2 Consortium. The chronic neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19: The need for a prospective study of viral impact on brain functioning. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeem, F.; Durrani, R.; Zerna, C.; Smith, E.E. Silent brain infarcts and cognitive decline: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajifathalian, K.; Kumar, S.; Newberry, C.; Shah, S.; Fortune, B.; Krisko, T.; Ortiz-Pujols, S.; Zhou, X.K.; Dannenberg, A.J.; Kumar, R.; et al. Obesity is Associated with Worse Outcomes in COVID-19: Analysis of Early Data from New York City. Obesity 2000, 28, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Misra, A. Post COVID-19 Syndrome (“Long COVID”) and Diabetes: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021, 15, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimercati, L.; De Maria, L.; Quarato, M.; Caputi, A.; Gesualdo, L.; Migliore, G.; Cavone, D.; Sponselli, S.; Pipoli, A.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Association between Long COVID and Overweight/Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, V.; Tzoulaki, I.; van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.; Evangelou, E.; Belbasis, L. Prognostic factors for adverse outcomes in patients with COVID-19: A field-wide systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2002964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Quan, L.; Chavarro, J.E.; Slopen, N.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Koenen, K.C.; Kang, J.H.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Branch-Elliman, W.; Roberts, A.L. Associations of Depression, Anxiety, Worry, Perceived Stress, and Loneliness Prior to Infection With Risk of Post–COVID-19 Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, D.M.; Basso, M.R.; Naini, S.M.; Porter, J.; Holker, E.; Waldron, E.J.; Melnik, T.E.; Niskanen, N.; Taylor, S.E. Outcomes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) at 6 months post-infection Part 1: Cognitive functioning. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 36, 806–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasserie, T.; Hittle, M.; Goodman, S.N. Assessment of the Frequency and Variety of Persistent Symptoms Among Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.; Ferrando, S.J.; Dornbush, R.; Shahar, S.; Smiley, A.; Klepacz, L. Screening for brain fog: Is the Montreal cognitive assessment an effective screening tool for neurocognitive complaints post-COVID-19? Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2022, 78, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012, 184, E191–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.H.; Lin, J.J.; Doernberg, M.; Stone, K.; Navis, A.; Festa, J.R.; Wisnivesky, J.P. Assessment of Cognitive Function in Patients After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2130645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Benito Ballesteros, A.; Yeung, S.P.; Liu, R.; Saha, A.; Curtis, L.; Kaser, M.; Haggard, M.P.; Cheke, L.G. COVCOG 2: Cognitive and Memory Deficits in Long COVID: A Second Publication From the COVID and Cognition Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 804937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.J.; Preston, N.; Parkin, A.; Makower, S.; Ross, D.; Gee, J.; Halpin, S.J.; Horton, M.; Sivan, M. The COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS): Application and psychometric analysis in a post-COVID-19 syndrome cohort. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, M.; Halpin, S.; Gee, J.; Makower, S.; Parkin, A.; Ross, D.; Horton, M.; O’Connor, R. The self-report version and digital format of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) for Long COVID or Post-COVID syndrome assessment and monitoring. Adv. Clin. Neurosci. Rehabil. 2021, 20, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Buss, U.; Snaith, R.P. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Deutsche Version (HADS-D); Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Monterrosa-Blanco, A.; Cassiani-Miranda, C.A.; Scoppetta, O.; Monterrosa-Castro, A. Generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) has adequate psychometric properties in Colombian general practitioners during COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2021, 70, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanipekun, T.; Abe, T.; Effoe, V.; Westney, G.; Snyder, R. Incidence and Severity of Depression Among Recovered African Americans with COVID-19-Associated Respiratory Failure. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Garro, P.A.; Aibar-Almazán, A.; Rivas-Campo, Y.; Vega-Ávila, G.C.; Afanador-Restrepo, D.F.; Hita-Contreras, F. Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Quality of Life, Mental Health, and Level of Physical Activity in Colombian University Workers: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpelli, S.; Alfonsi, V.; Mangiaruga, A.; Musetti, A.; Quattropani, M.C.; Lenzo, V.; Freda, M.F.; Lemmo, D.; Vegni, E.; Borghi, L.; et al. Pandemic nightmares: Effects on dream activity of the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taporoski, T.P.; Beijamini, F.; Gómez, L.M.; Ruiz, F.S.; Ahmed, S.S.; von Schantz, M.; Pereira, A.C.; Knutson, K.L. Subjective sleep quality before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Brazilian rural population. Sleep Health 2022, 8, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacof, L.; Tosto-Mancuso, J.; Wood, J.; Cortes, M.; Kontorovich, A.; McCarthy, D.; Rizk, D.; Rozanski, G.; Breyman, E.; Nasr, L.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome negatively impacts physical function, cognitive function, health-related quality of life and participation. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Normand, K.; Zhaoyun, Y.; Torres-Castro, R. Long-Term Impact of COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Literature and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage-Don, N.A.; Winawer, M.R.; Hamberger, M.J.; Agarwal, S.; Trainor, A.R.; Quispe, K.A.; Kronish, I.M. Association of depression and COVID-induced PTSD with cognitive symptoms after COVID-19 illness. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2022, 76, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P.; Weathers, F.W.; Gallagher, M.W.; Rodriguez, P.; Schnurr, P.P.; Keane, T.M. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol. Assess 2016, 28, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, F.A.; Boon, G.J.A.M.; Barco, S.; Endres, M.; Geelhoed, J.J.M.; Knauss, S.; Rezek, S.A.; Spruit, M.A.; Vehreschild, J.; Siegerink, B. The Post-COVID-19 Functional Status scale: A tool to measure functional status over time after COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2001494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.E.; Haroon, S.; Subramanian, A.; McMullan, C.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Turner, G.M.; Jackson, L.; Davies, E.H.; Frost, C.; McNamara, G.; et al. Development and validation of the symptom burden questionnaire for long COVID (SBQ-LC): Rasch analysis. BMJ 2022, 377, e070230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raciti, L.; Arcadi, F.A.; Calabrò, R.S. Could Palmitoylethanolamide Be an Effective Treatment for Long-COVID-19? Hypothesis and Insights in Potential Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Applications. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 19, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nurek, M.; Rayner, C.; Freyer, A.; Taylor, S.; Järte, L.; MacDermott, N.; Delaney, B.C.; Panellists, D. Recommendations for the recognition, diagnosis, and management of long COVID: A Delphi study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e815–e825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compagno, S.; Palermi, S.; Pescatore, V.; Brugin, E.; Sarto, M.; Marin, R.; Calzavara, V.; Nizzetto, M.; Scevola, M.; Aloi, A.; et al. Physical and psychological reconditioning in long COVID syndrome: Results of an out-of-hospital exercise and psychological—Based rehabilitation program. Int. J. Cardiology. Heart Vasc. 2022, 41, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, J.S.; Ambrose, A.F.; Didehbani, N.; Fleming, T.K.; Glashan, L.; Longo, M.; Merlino, A.; Ng, R.; Nora, G.J.; Rolin, S.; et al. Multi-disciplinary collaborative consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of cognitive symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). PMR J. Inj. Funct. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonova, E.; Schlosser, K.; Pandey, R.; Kumari, V. Coping With COVID-19: Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Mitigating Mental Health Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 563417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryan, E.M.; Davis, E.; Beadel, J.R.; Tolin, D.F. Brief adjunctive mindfulness-based cognitive therapy via Telehealth for anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping 2022, 2022, e2117305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilbeck, L. Patient-led integrated cognitive behavioral therapy for management of long COVID with comorbid depression and anxiety in primary care—A case study. Chronic Illn. 2022, 18, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathern, R.; Senthil, P.; Vu, N.; Thiyagarajan, T. Neurocognitive Rehabilitation in COVID-19 Patients: A Clinical Review. South. Med. J. 2022, 115, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

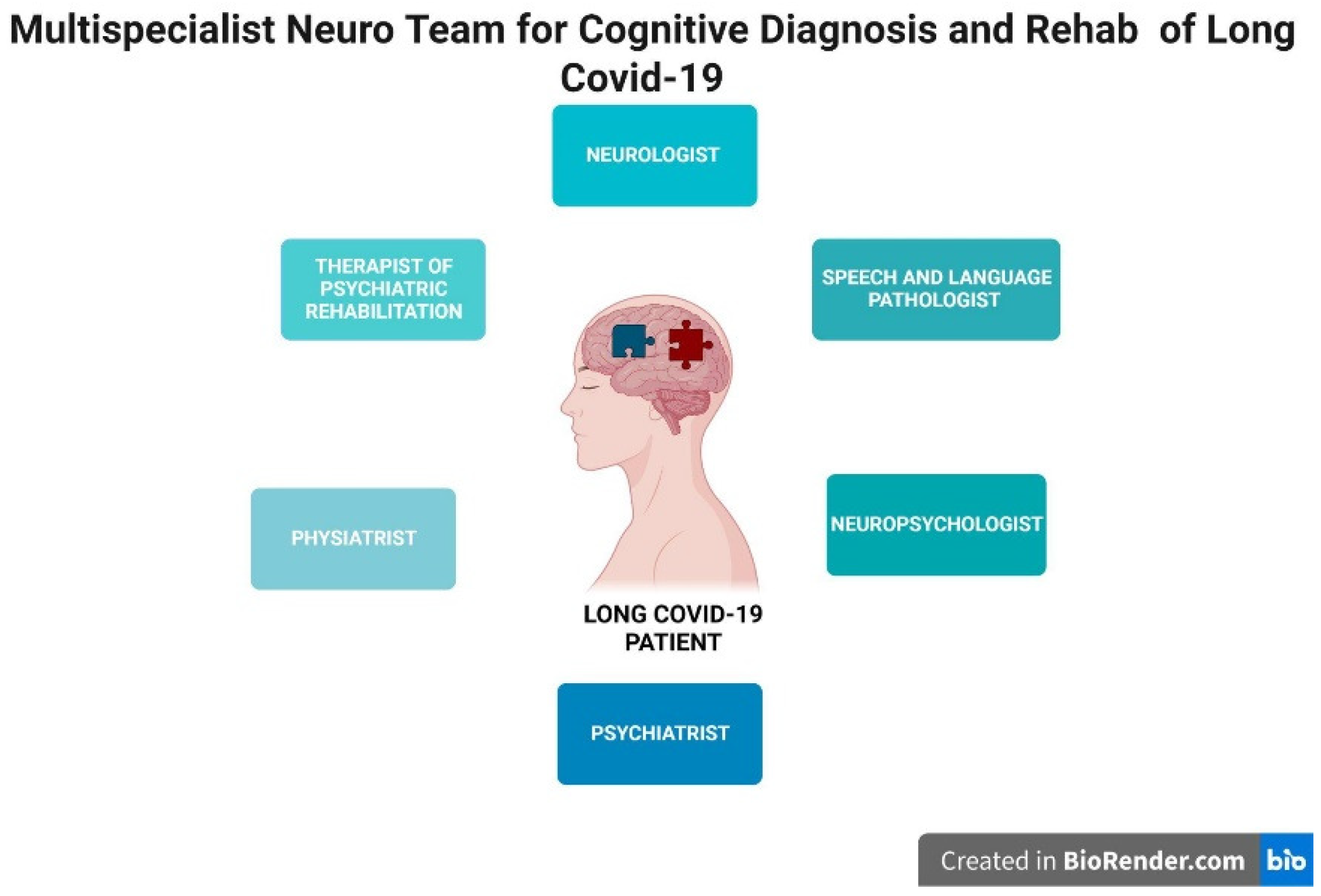

- Illustration Created by. Available online: https://biorender.com/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- García-Molina, A.; Espiña-Bou, M.; Rodríguez-Rajo, P.; Sánchez-Carrión, R.; Enseñat-Cantallops, A. Neuropsychological rehabilitation program for patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome: A clinical experience. Neurologia 2021, 36, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolin, S.; Chakales, A.; Verduzco-Gutierrez, M. Rehabilitation Strategies for Cognitive and Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of COVID-19. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2022, 10, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.E.; Niehaus, W.N.; Whiteson, J.; Azola, A.; Baratta, J.M.; Fleming, T.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Naqvi, H.; Sampsel, S.; Silver, J.K.; et al. Multidisciplinary collaborative consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of fatigue in postacute sequelae of SARS-COV-2 infection (PASC) patients. PM&R 2021, 13, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daynes, E.; Gerlis, C.; Chaplin, E.; Gardiner, N.; Singh, S.J. Early experiences of rehabilitation for individuals post-COVID to improve fatigue, breathlessness, exercise capacity and cognition-a cohort study. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2021, 18, 147997312110156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenveld, T.; Achttien, R.; Smits, M.; de Vries, M.; van Heerde, R.; Staal, B.; van Goor, H.; COVID Rehab Group. Feasibility of Virtual Reality Exercises at Home for Post-COVID-19 Condition: Cohort Study. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 9, e36836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbe, L.; Jaywant, A.; Gupta, A.; Vanderlind, W.M.; Jabbour, G. Use of virtual reality in the inpatient rehabilitation of COVID-19 patients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2021, 71, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.G.; De Luca, R.; Manuli, A.; Calabrò, R.S. The five ‘W’ of cognitive telerehabilitation in the COVID-19 ERA. Expert Rev. Med. Devices. 2020, 17, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Calabrò, R.S. How the COVID-19 Pandemic is Changing Mental Health Disease Management: The Growing Need of Telecounseling in Italy. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 17, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bernini, S.; Stasolla, F.; Panzarasa, S.; Quaglini, S.; Sinforiani, E.; Sandrini, G.; Vecchi, T.; Tassorelli, C.; Bottiroli, S. Cognitive Telerehabilitation for Older Adults With Neurodegenerative Diseases in the COVID-19 Era: A Perspective Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 623933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, T.; Ramage, M.; LaBruyere, J.T.; McLean, W.; Tak, C.R. Telemedicine Services during COVID-19: Considerations for medically underserved populations. J. Rural. Health 2020, 37, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Rifici, C.; Pollicino, P.; Di Cara, M.; Miceli, S.; Sergi, G.; Sorrenti, L.; Romano, M.; Naro, A.; Billeri, L.; et al. ‘Online therapy’ to reduce caregiver’s distress and to stimulate post-severe acquired brain injury motor and cognitive recovery: A Sicilian hospital experience in the COVID era. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfarpour, M.; Ashrafinia, F.; Zolala, S.; Ahmadi, A.; Jahani, Y.; Hosseininasab, A. Investigating the effectiveness of tele-counseling for the mental health of staff in hospitals and COVID-19 clinics: A clinical control trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, Y.T.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e17–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czura, C.J.; Bikson, M.; Charvet, L.; Chen, J.; Franke, M.; Fudim, M.; Grigsby, E.; Hamner, S.; Huston, J.M.; Khodaparast, N.; et al. Neuromodulation Strategies to Reduce Inflammation and Improve Lung Complications in COVID-19 Patients. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 897124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, R. Neuroimmune interactions: From the brain to the immune system and vice versa. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabel, B.A.; Zhou, W.; Huber, F.; Schmidt, F.; Sabel, K.; Gonschorek, A.; Bilc, M. Non-invasive brain microcurrent stimulation therapy of long-COVID-19 reduces vascular dysregulation and improves visual and cognitive impairment. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2021, 39, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thams, F.; Antonenko, D.; Fleischmann, R.; Meinzer, M.; Grittner, U.; Schmidt, S.; Brakemeier, E.L.; Steinmetz, A.; Flöel, A. Neuromodulation through brain stimulation-assisted cognitive training in patients with post-COVID-19 cognitive impairment (Neuromod-COV): Study protocol for a PROBE phase IIb trial. BMJ Open 2020, 12, e055038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Neuropsychological Measures | Domain | Short Description |

|---|---|---|

| Adapted assessment tools for Long COVID | ||

| Mini Mental State Examination—MMSE (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Global Cognitive Status in Long COVID subjects with moderate and severe cognitive deterioration. | MMSE is a psychometric test commonly used for screening global cognitive functioning. It consists of eleven questions and takes only 5–10 min to administer. It is a 30-point test used to measure some specific cognitive domains:

|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment—MoCA (Lynch et al., 2022) [83] | Global cognitive functioning in Long COVID subjects with mild–moderate and severe neuropsychological sequelae | The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a widely used screening assessment for detecting cognitive impairment. It was validated as a highly sensitive tool for early detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in 2000. MoCA accurately and quickly assesses:

|

| Trail Making Test Part A and Part B—TMT A and B (Becker et al., 2021) [86] | Processing speed Executive functioning | TMT consists of 25 circles distributed over a sheet of paper. In Part A, the circles are numbered 1–25, and the patient should draw lines to connect the numbers in ascending order. In Part B, the circles include both numbers (1–13) and letters (A–L); as in Part A, the patient draws lines to connect the circles in an ascending pattern but with the added task of alternating between the numbers and letters (i.e., 1-A-2-B-3-C, etc.). The patient should be instructed to connect the circles as quickly as possible without lifting the pen or pencil from the paper. The patient is timed as he or she connects the “trail”. Results for both TMT A and B are reported as the number of seconds required to complete the task; therefore, higher scores reveal greater impairment. |

| Saint Louis University Mental—SLUMS (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Cognitive impairment | SLUMS measures diverse aspects of cognition. It consists of 11 questions that help a healthcare provider evaluate:

|

| Mini-Cog—MC (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Short-term memory learning | The Mini-Cog is a 3 min instrument that can increase detection of cognitive impairment in older adults. It combines a short memory test with a simple clock-drawing test to enable fast screening for short-term memory problems, learning disabilities, and other cognitive functions that are reduced in dementia patients. |

| Short Test of Mental Status—STMS (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Global cognition | The Short Test of Mental Status can be administered to patients in approximately 5 min, and it contains items that test orientation, attention, immediate recall, arithmetic, abstraction, construction, information, and delayed (approximately 3 min) recall. |

| Digit Span—DGS (Fine et al., 2022) [105] Number span forward and backward (Becker et al., 2021) [86] | Attention and working memory | Digit Span (DGS) is a measure of verbal short-term and working memory. DGS can be used in two formats, Forward Digit Span and Reverse Digit Span. This is a verbal task, with stimuli presented auditorily, and responses spoken by the participant and scored automatically by the software. Participants are presented with a random series of digits and are asked to repeat them in either the order presented (forward span) or in reverse order (backwards span). |

| Digit Vigilance Test—DVT (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Sustained attention | The DVT is a simple task designed to measure vigilance during rapid visual tracking and accurate selection of target stimuli. It focuses on alertness and vigilance, while placing minimal demands on two other components of attention: selectivity and capacity. |

| Cancellation test (Albert’s Test)—CT-AT (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Unilateral spatial neglect (USN) visuo-spatial research | Albert’s Test is commonly a visual neglect screen that requires patients to cross out lines on a single piece of paper. |

| Letter Fluency Test—LFT adapted tool (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Phonemic verbal fluency | Verbal fluency tests are brief assessment tools with relatively simple administration and scoring procedures. Semantic and phonemic fluency are measures of non-motor processing speed, language production, and executive functions. In particular, the Phonemic Verbal Fluency Test was shown to be sensitive for assessment of functional communication skills, commonly used for aphasic patients. Letter fluency is also referred to as phonemic test fluency. |

| Category Fluency Test—CFT (Guo et al., 2022) [87] | Semantic/Category fluency | Verbal fluency tests are a kind of psychological test in which participants have to produce as many words as possible from a category in a given time (usually 60 s). This category can be semantic, including objects such as animals or fruits, or phonemic, including words beginning with a specified letter, such as p, for example. The semantic fluency test is sometimes described as the category fluency test or simply as “free listing”. |

| Boston Naming Test—BNT (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Denomination language abilities | The Boston Naming Test (BNT) is a widely used neuropsychological assessment tool to measure confrontational word retrieval in individuals with aphasia or other language disturbances caused by stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, or other dementing disorders. The BNT contains 60 line drawings graded in difficulty. Patients with anomia often have greater difficulties with the naming of not only difficult and low-frequency objects but also easy and high-frequency objects. |

| Brief Visual Memory Test—BVMT (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Visuo-spatial learning and memory | The brief visuo-spatial memory test-revised (BVMT-R) assesses visuo-spatial learning and memory in adults. It has equivalent forms that allow reassessing of patients. |

| Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test—R-OCFT (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Visuo-spatial abilities, memory, attention, planning, working memory, and executive functions | The Rey–Osterrieth complex figure (ROCF) is a neuropsychological assessment in which examinees are asked to reproduce a complicated line drawing, first by copying it freehand (recognition), and then drawing from memory (recall). |

| Wechsler Memory Scale-IV—WMS-IV (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Memory functions | The Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) is a neuropsychological test designed to measure different memory functions. A person’s performance is reported as five index scores: Auditory Memory, Visual Memory, Visual Working Memory, Immediate Memory, and Delayed Memory. |

| State Trait Inventory of Cognitive Fatigue (STI-CF) (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Cognitive fatigue | The STI-CF is a 32-item subjective measure of cognitive fatigue. It refers to low alertness and cognitive impairment. |

| Stroop Color Word—SCW (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Executive functions | The Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT) is a neuropsychological test extensively used to assess the ability to inhibit cognitive interference that occurs when the processing of a specific stimulus feature impedes the simultaneous processing of a second stimulus attribute, known well as the Stroop Effect. |

| Tower of London—TOL (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Executive functions | The Tower of London test is a test used in applied clinical neuropsychology for the assessment of executive functioning, specifically to detect deficits in planning, which may occur due to a variety of medical and neuropsychiatric conditions. |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test—WCST (Guo et al., 2022) [87] | Executive functions | The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) is a neuropsychological test that is frequently used to measure such higher-level cognitive processes as attention, perseverance, working memory, abstract thinking, category fluency, and set shifting. The WCST consists of two card packs with four stimulus cards and 64 response cards in each. |

| Word List Recognition Memory Test—WLRMT (Guo et al., 2022) [87] | Verbal memory learning | Wordlist memory tests are commonly used for cognitive assessment, particularly in Alzheimer’s disease research and screening. Commonly used tests employ a variety of inherent features, such as list length, number of learning trials, order of presentation across trials, and inclusion of semantic categories. |

| Pictorial Associative Memory Test—PAMT (Guo et al., 2022) [87] | Visual associative memory | Picture Memory Impairment Screen for People with Intellectual Disability (PMIS-ID). The PMIS-ID consists of four-color photographs semantically unrelated in each quadrant. It includes four distinct parts: Identification (I), Learning (L), Immediate Recall (IR), and Delayed Recall (DR) |

| Mental Rotation Test—MRT (Guo et al., 2022) [87] | Spatial abilities/Mental rotation | The Mental Rotations Test is a test of spatial ability. Mental rotation time is defined as the time it takes someone to find out if a stimulus matches another stimulus through mental rotation. |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Herrmann-Lingen et al., 2011) [90] | Depression and anxiety symptoms | HADS-A consists of 7 items assessing anxiety symptoms, whereas HADS-D consists of 7 items evaluating depressive symptoms. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3), providing a maximum of 21 points for each subscale. It is a patient-reported outcome measure for evaluating the emotional consequences of SARS-CoV-2 in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors with Long COVID. |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al. 2006; Monterrosa-Blanco et al., 2021) [84,91] | Anxiety and related symptoms | GAD-7 is a screening and monitoring test for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. It is not a replacement for a diagnosis from a doctor. The answers to each question are given a value from 0 to 3 depending on severity. |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9, (PHQ-9) (Olanipekun et al., 2022) [92] | Depression symptoms | The PHQ-9 is the depression module, which scores each of the nine DSM-IV criteria as “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). It has been validated for use in primary care. It is not a screening tool for depression, but it is used to monitor the severity of depression and the response to treatment. |

| Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZSDS) (García-Garro et al., 2022) [93] | Depression symptoms | Depression was assessed using the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZSDS). This instrument consists of 20 questions split into 10 positive and 10 negative questions related to the frequency of depressive symptoms (DS). Each question receives a score between 1 and 4 (a little of the time = 1; some of the time = 2; good part of the time = 3; most of the time = 4), which means that the total score can range between 20 and 80 points, where higher scores are related to the presence of DS. For dichotomization, a global score of 55 points was taken as the cut-off point, resulting in two categories: with DS (>55) and without DS (≤55). |

| Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) (Scarpelli et al., 2021) [94] | Insomnia—Sleeping difficulty | The Medical Outcomes Study-Sleep Scale is a self-administered questionnaire with 12 items to assess sleep quality and quantity within 4 weeks (details in the online supporting information). Three variables were extracted from the MOS-SS for further analyses: (a) the Sleep Index II or sleep problem index, an aggregate measure of responses concerning four sleep domains (sleep disturbance, awakening with shortness of breath or with headache, sleep adequacy, and somnolence), as a synthetic measure of sleep quality; (b) sleep duration (item 2); and (c) self-reported evaluation of intrasleep wakefulness (item 8), dichotomized as follows: ‘‘high intrasleep wakefulness’’ (answer 3, 4, or 5) and ‘‘low intrasleep wakefulness’’ (answer 1 or 2). |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Taporoski et al., 2022) [95] | Sleep quality | The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess the participants’ sleep quality. The PSQI is composed of 24 questions and measures seven different domains: (i) sleep latency, (ii) subjective sleep quality, (iii) daytime dysfunctions, (iv) sleep duration, (v) sleep disturbances, (vi) habitual sleep efficiency, and (vii) use of sleep medications, generating a global score. Each domain can be scored between 0 and 3 points, resulting in a global score ranging from 0 to 21, where higher scores are related to worse sleep quality. |

| EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) (Tabacof et al., 2022) [96] | Health-related quality of life | EQ-5D is an instrument which evaluates the generic quality of life developed in Europe and is widely used. The EQ-5D descriptive system is a preference-based HRQL measure with one question for each of the five dimensions, which include mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. |

| FACIT-Fatigue scale (Sanchez-Ramirez et al., 2021) [97] | Fatigue | Fatigue was assessed using the 13-item FACIT fatigue scale, a widely used and validated self-report questionnaire to assess symptoms on a five-point Likert-scale with a sum score ranging from 0 (worst fatigue) to 52 (no fatigue). Clinically relevant fatigue was defined by scores ≤ 30, as suggested by the creators of the scale, based on general population data. |

| Checklist for DSM 5 (PCL-5) (Liyanage-Don et al., 2022; Bovin et al., 2016) [98,99] | Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSD) | The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure of the 20 DSM-5 symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Included in the scale are four domains consistent with the four criteria of PTSD in DSM-5: Re-experiencing (criterion B) Avoidance (criterion C); Negative alterations in cognition and mood (criterion D); Hyper-arousal (criterion E). The PCL-5 can be used to monitor symptom change, to screen for PTSD, or to make a provisional PTSD diagnosis. |

| “Newly” Designed tools for Long COVID | ||

| COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) (O’Connor et al., 2022; Sivan et al., 2021) [88,89] | Persistent COVID-19 symptoms | The C19-YRS outcome measure is a clinically validated screening tool recommended for use, consisting of 22 items with each item rated on an 11-point numerical rating scale from 0 (none of this symptom) to 10 (extremely severe level or impact). The C19-YRS is divided into four subscales (range of total score for each subscale): symptom severity score (0–100), functional disability score (0–50), additional symptoms (0–60), and overall health (0–10). |

| Post-COVID-19 Functional Status scale (PCFS) (Klok et al., 2020) [100] | Post-COVID-19 functional symptoms | PCFS is a tool to measure functional status over time after COVID-19. The PCFS scale stratification is composed of five scale grades: grade 0 (No functional limitations); grade 1 (Negligible functional limitations); grade 2 (Slight functional limitations); grade 3 (Moderate functional limitations) and grade 4 (Severe functional limitations). The final scale grade 5 is ‘death’, which is required to be able to use the scale as an outcome measure in clinical trials, but was left out for this self-administered questionnaire. |

| Symptom burden questionnaire for Long COVID (SBQ-LC) (Hughes et al., 2021) [101] | Long COVID burden | The SBQ-LC includes 16 symptom scales, each measuring a different symptom domain and a single-scale measuring symptom interference. It is a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure and a multi-domain item bank that has been developed according to international best-practice and regulatory guidance. The SBQ™-LC system measures symptom burden in adults (18+ years) with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), also known as “post COVID-19 condition” or “Long COVID”. |

| Task Domain–Specific | Conventional Approach Face to Face with Therapist Paper/Pencil Tasks | Advanced Approach PC-Based/Virtual Setting/Assistent Software Dedicated/Virtual Task | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention processes Well-being | Reference | Training and Major Findings | Reference | Training and Major Findings |

| (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Attention Process Training—APT (For verbal and nonverbal tasks, metacognitive strategies, timed structured activities, minimized distractions) was mentioned in the treatment recommendations, as possible therapeutic intervention strategy. | (Kolbe et al., 2021) [116] | Virtual Reality Rehabilitation The authors implemented a VR program for COVID-19 subjects. The rehabilitation unit for patients and healthcare providers was rated as highly satisfactory with perceived benefit for enhancing patient treatment and healthcare staff well-being, improving outcomes, such as mood, anxiety, sleep, pain, and feelings of isolation. | |

| Coping, Cognition, and Mental Health | (Antonova et al., 2022) [106] | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy These authors recommended the provision of mindfulness-based support during the COVID-19 pandemic to promote a more positive effect on well-being, as avoidance-type coping with stress and anxiety in COVID-19 context. | (O’Bryan et al., 2022) [107] | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy via telehealth—MBCT According to these authors, MBCT (as an adjunctive treatment for anxiety via telehealth) can be considered a feasible and acceptable treatment and a promising treatment for reducing anxiety symptoms. |

| (Sabel et al., 2022) [126] | Non-invasive brain stimulation using microcurrent (NIBS) NIBS can improve sensory and cognitive deficits in individuals suffering from Long COVID. Controlled trials are now needed to confirm these observations. | |||

| (Czurra et al., 2022) [124] | Non invasive—Neuromodulation Strategies The authors have supported studies of NIBS in the current coronavirus pandemic. Neuromodulatory techniques provide a rationale for testing non-invasive neuromodulation to reduce an acute systemic inflammation and respiratory dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2, with beneficial role for psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety. | |||

| Visuo-Research/Visuo-construction Skills Satisfaction Working Memory | (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Visuo-spatial exercise programs (i.e., the use of visual cancellation tasks and strategies for visual organization, such as scanning from left to right, top to bottom, for symbols, shapes, numbers, etc.) were mentioned in the treatment recommendations, as therapeutic intervention strategies. | (Kolbe et al., 2021) [116] | Virtual Reality Rehabilitation The authors considered the use of VR that could be implemented within the context of clinical care for COVID-19 patients and both patients and staff members reported overall positive satisfaction and perceived benefit with VR as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation model. |

| (Thams et al., 2022) [127] | Study protocol for a PROBE—phase IIb trial on brain stimulation-assisted cognitive training. Cognitive training group will additionally receive anodal tDCS, all other patients will receive sham tDCS (double-blinded, secondary intervention). Primary outcome: to improve working memory performance at the post-intervention assessment. Secondary outcomes: to increase health-related quality of life at post-assessment and follow-up Assessments (1 month after the end of the training). | |||

| Executive Functions Social Functioning | (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Metacognitive strategies Problem-solving training (examples of metacognitive strategies: Goal–Plan–Do–Review, Self-talk, Goal Management Training (Stop– Think–Plan), Predict–Perform Technique). These therapeutic interventions strategies are reported as treatment recommendations by the authors. | (Maggio et al., 2020) [117] | Cognitive tele-rehabilitation home-based exercises The authors analyzed the role of cognitive tele-rehabilitation following the journalistic ‘5W’ (what, where, who, when, why), taking into account the growing interest in this matter in the ‘COVID Era’, and also promoting the practice of the human–technology interaction to improve social functioning and psychological well-being by also avoiding isolation. |

| (Bernini et al., 2021) [119] | Tele-rehabilitation Home Cognitive Rehabilitation software (HomeCoRe). Authors suggested that HomeCoRe software could be incorporated as a valid support into clinical routine protocols as a complementary non-pharmacological therapy to support the continuum of care from the hospital to the patient’s home. | |||

| Communication Pragmatic Language skills | (Fine et al., 2022) [105] | Compensatory strategies/aids; writing and organization, use of language-mediated strategies such as self-talk or verbalization to solve problems or remember information (i.e., structured tasks to address various domains, such as comprehension, recall, word finding, thought organization), were described as therapeutic intervention strategies, reported in treatment recommendations. | (De Luca et al., 2020) [118] | Tele-counseling In Italy, psychological tele-counseling has been an effective method of supporting the physical and psychosocial needs of all patients, regardless of their geographical locations. In this commentary, the authors promoted the use of telehealth as an effective tool for treating patients with mental health illness, specifically, as a growing need during the COVID era. |

| Emotions/Mood Quality of Life Caregiver Distress | (Skilbeck et al., 2022) [108] | Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) This study illustrated the use of patient-led CBT for managing symptoms of Long COVID with comorbid depression and anxiety in primary care, showing reliable change in somatic, depression, and anxiety symptoms and quality of life. | (Woodall et al., 2020) [120] | Telemedicine Service/Online therapy during COVID-19. This commentary explored the use of telemedicine in reaching under-served COVID-19 patients. The authors recommended the use of telemedicine that may be helpful to limit transportation, distance, or mobility challenges, reducing physical and psychological distances. |

| (Liu et al., 2020) [123] | Online therapy The authors illustrated how the main online mental health services (including online mental health education with communication programmes and online psychological counseling services) being used for the COVID-19 epidemic are facilitating the development of Chinese public emergency interventions and eventually could improve the quality and effectiveness of emergency interventions. | |||

| (De Luca et al., 2021) [121] | Skype therapy (OLST) The authors showed that OLST may be of support in favoring global cognitive and sensory-motorrecovery in Severe Acquired Brain Injury (SABI) patients and reducing caregiver distress during COVID-19 era. | |||

| Neuropsychiatric sequelae | (Rolin et al., 2022) [112] | Rehabilitation Strategies Neuropsychiatric manifestation (psychoeducation, anxiety modulation psychotherapy, psychopharmacology, and peer support). These authors supported the idea that multidisciplinary rehabilitation of the cognitive and neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 during all levels of care is essential. An approach combining general medical, neurological, and neuropsychological intervention is recommended. | (Ghazanfarpour, et al., 2021) [122] | Tele-counseling The authors suggested that a systematic monitoring of the negative psychological impacts on medical staff is needed, as well as the implementation of appropriate tele-interventions to improve medical staff mental health of those working in hospitals and COVID-19 clinics. |

| Physical Function Cognition | (Daynes et al., 2021) [114] | Endurance and balance training The authors developed an adapted rehabilitation programme for individuals following COVID-19 that has demonstrated feasibility and promising improvements in clinical outcomes, with significant improvements in walking capacity, symptoms of fatigue, cognition, and respiratory symptoms. | (Groenveld et al., 2022) [115] | Virtual reality exercise at home The authors have investigated the feasibility of self-administered VR exercises at home for the post-COVID-19 condition, demonstrating that the use of VR for physical and self-administered mental exercising at home is well tolerated and appreciated in patients with a post–COVID-19 condition. Physical function outcomes registered positive health, and quality of life improved in time, whereas cognitive function seemed unaltered. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Luca, R.; Bonanno, M.; Calabrò, R.S. Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long COVID: A Narrative Review Focusing on the Assessment and Rehabilitative Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216554

De Luca R, Bonanno M, Calabrò RS. Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long COVID: A Narrative Review Focusing on the Assessment and Rehabilitative Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(21):6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216554

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Luca, Rosaria, Mirjam Bonanno, and Rocco Salvatore Calabrò. 2022. "Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long COVID: A Narrative Review Focusing on the Assessment and Rehabilitative Approach" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 21: 6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216554

APA StyleDe Luca, R., Bonanno, M., & Calabrò, R. S. (2022). Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long COVID: A Narrative Review Focusing on the Assessment and Rehabilitative Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(21), 6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216554